Abstract

Objective:

Factors in the practice environment, such as health information technology (IT) infrastructure, availability of other clinical resources, and financial incentives, may influence whether practices are able to successfully implement the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model and realize its benefits. This study investigates the impacts of those PCMH-related elements on primary care physicians’ perception of quality of care.

Methods:

A multiple logistic regression model was estimated using the 2004 to 2005 CTS Physician Survey, a national sample of salaried primary care physicians (n = 1733).

Results:

The patient-centered practice environment and availability of clinical resources increased physicians’ perceived quality of care. Although IT use for clinical information access did enhance physicians’ ability to provide high quality of care, a similar positive impact of IT use was not found for e-prescribing or the exchange of clinical patient information. Lack of resources was negatively associated with physician perception of quality of care.

Conclusion:

Since health IT is an important foundation of PCMH, patient-centered practices are more likely to have health IT in place to support care delivery. However, despite its potential to enhance delivery of primary care, simply making health IT available does not necessarily translate into physicians’ perceptions that it enhances the quality of care they provide. It is critical for health-care managers and policy makers to ensure that primary care physicians fully recognize and embrace the use of new technology to improve both the quality of care provided and the patient outcomes.

Keywords: health information technology, patient-centered practice environment, primary care physicians

Care that is responsive to individual patient values and needs1 is central to primary care in the United States and is a core component of the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model that has become the centerpiece of health care delivery reform.2,3 Studies have found that provision of patient-centered care is associated with higher patient engagement, satisfaction, and reduced health care costs.4,5 Despite these benefits, implementing patient-centered care can be challenging for primary care teams, particularly within the context of the PCMH model. Adopting a team-based, patient-centered approach often requires significant changes to traditional patterns of interaction and can be costly and time consuming for primary care practices.6,7

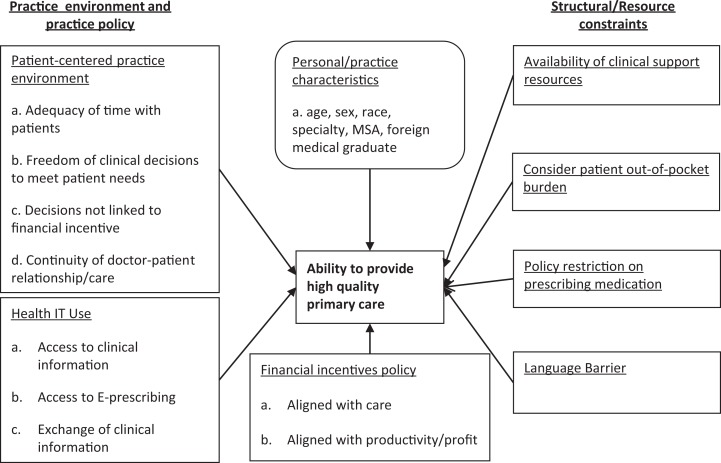

Factors in the practice environment, such as health information technology (IT) infrastructure, availability of other clinical resources, and financial incentives, may influence whether practices are able to successfully implement the PCMH model and realize its benefits. Health IT has the potential to facilitate patient-centered care by improving care coordination and enhancing patient–provider communication.8,9 However, despite significant growth in health IT infrastructure over the last decade, primary care physicians do not sufficiently utilize health IT to ensure high-quality primary care.10,11 Although some have shown that greater use of health IT can increase physicians’ ability to provide high-quality primary care in a patient-centered environment,12 full realization of its potential may require a stronger perception that IT improves both the quality of care provided and the patient outcomes. This study investigates the impacts of the patient-centered practice environment and health IT use on primary care physicians’ perceived confidence in providing high-quality primary care. The comprehensive research framework shown in Figure 1 illustrates how many PCMH-related elements are associated with physicians’ perception of quality of care.

Figure 1.

Research Framework.

Methods

This study analyzed data from the 2004 to 2005 Community Tracking Study Physician Survey because it is the only large national survey that includes measures such as practice policy, medical care management, patient relationships, and physician compensation.13 The sample consisted of salaried primary care physicians, who have become more prevalent in primary care delivery.14 A total of 1733 salaried primary care physicians, who are board certified in family medicine, internal medicine, or pediatrics, were selected.

Study Variables

Table 1 lists all variables included in this study. Appendix A provides the original survey questions from which these variables were defined.

Table 1.

Summary of Study Variables.

| Type of Variable (# Original Questions) | Reference Group | Variables in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent | ||

| Ability to provide quality care | =1 if strongly agree able to provide high-quality care to all patients | |

| Independent | ||

| Patient-centered practice environment (n = 4) | Mean score on practice environment measures (5-point scale) | |

| Health IT functionality | ||

| Access to clinical information (n = 4) | No clinical IT use | =1 if use all 4 clinical IT functions |

| =1 if use 3 clinical IT functions | ||

| =1 if use 2 clinical IT functions | ||

| =1 if use 1 clinical IT function | ||

| Use of e-prescription (n = 2) | No E-prescription use | =1 if both E-prescription uses |

| =1 if only 1 E-prescription uses | ||

| Exchange clinical information (n = 2) | No information exchange functions | =1 if 2 information exchange functions |

| =1 if 1 information exchange function | ||

| Resource constraints | ||

| Availability of clinical support resources (n = 4) | ≤2 resources available | =1 if ≥3 resources available |

| Consider patient out-of-pocket burden (n = 2) | Mean value < 4 | =1 if mean value ≥4 (5-point scale) |

| Policy restrictions on prescribing medication (n = 1) | Percent <80% | =1 if percent ≥80% |

| Physician financial incentives | ||

| Aligned with care quality/content (n = 3) | Mean score of 3 incentives | |

| Aligned with productivity/profitability (n = 2) | Mean score of 2 incentives | |

| Physician and practice characteristics | ||

| Age | Years | |

| Gender | Male | =1 if female |

| Race | White | =1 if black |

| =1 if other | ||

| Specialty | Pediatrics | =1 if family practice |

| =1 if internal medicine | ||

| Practice type | Clinic/office with 1-2 physicians | =1 if clinic/office with 3+ physicians |

| =1 if HMO | ||

| =1 if medical school | ||

| =1 if hospital | ||

| =1 if other | ||

| Size of practice area | Large metropolitan area | =1 if small metro area |

| =1 if nonmetro area | ||

| FMG | US degree | =1 if foreign medical degree |

| % patients with foreign language | % patients with primary language not English | |

Abbreviations: FMG, Foreign Medical Graduate; IT, information technology.

Confidence in providing high-quality care

The outcome variable was primary care physicians’ self-assessed confidence in providing high-quality care. Instead of a highly specific outcome measure that may be an unreliable or invalid proxy for actual quality, this study used perceived quality of care by primary care physicians, who are the appropriate persons to make clinical decisions for patients. The dependent variable for this analysis is based on recoding a self-assessed measure (1: strongly disagree to 5: strongly agree) into a dichotomous variable (strongly agree vs all other responses) to investigate whether health IT contributes to the strongest perception of quality care. The distribution of data for the original variable did not allow for robust estimation of additional intervals.

Patient-centered practice environment

The patient-centered practice environment was defined using 4 items specific to the interpersonal dimension between doctors and patients15: (1) ability to maintain a long-term relationship with patients, (2) spending enough time with patients during office visits, (3) freedom to make clinical decisions in the best interest of patients, and (4) clinical freedom to make decisions that meet patients’ needs. These 4 items are consistent with the widely endorsed PCMH definition as “a model of care that strengthens the clinician-patient relationship by replacing episodic care with coordinated care and a long-term healing relationship, p.2.”16 They were averaged into a single score for the empirical analysis.

Health IT use

Three types of IT functionalities were selected that represent the core of meaningful use in clinical practice: clinical information access, e-prescribing, and information exchange. The IT use for clinical information access was based on 4 survey items measuring whether physicians (1) obtain treatment alternatives or guideline, (2) generate preventive service reminders, (3) access patient notes and medication/problem lists, or (4) identify potential drug interaction with other drugs, allergies, and other patient conditions. E-prescribing was defined as the use of IT systems to write a prescription regardless of the type of system or the organization’s IT capacity and included the use of IT to (1) obtain information on formularies or (2) write prescriptions. An additional dimension of IT use was whether physicians exchanged patient information with (1) other physicians or (2) hospitals or laboratories. Separate variables were created for each of these 3 health IT dimensions based on the number of IT functions used.

Resource/structural constraints and financial incentives

Other variables were created to control separately for constraints that may influence physician’s perceived quality of care. These variables captured (1) the availability of supportive or referral resources, (2) the degree to which physicians consider their patients’ out-of-pocket financial burden, and (3) constraints in prescribing medications. Two additional variables measured the impact on quality of care of financial incentives aligned with quality or profitability of the practice.17

Physician age, gender, race, practice type, practice area, foreign medical degree status, and the percentage of patients whose primary language is not English were included in the multiple logistic regression model to capture the independent impact of these physician and practice characteristics on perceived quality of care.

Results

Primary care physicians in this sample are generally younger (36.5% younger than 40 years old), male (60.3%), and white (73.9%). Family/general practitioners were the most frequently reported specialty (39.7%), and the majority (83.5%) of physicians practiced in a large metropolitan area (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics and Descriptive Results of Study Variables.a

| Study Variables | Groups | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ≤40 | 600 (36.5) |

| 41-50 | 562 (32.4) | |

| 51-60 | 382 (22.1) | |

| >60 | 156 (9.0) | |

| Gender | Male | 1046 (60.3) |

| Female | 687 (39.7) | |

| Race | White | 1230 (73.9) |

| Black | 119 (7.0) | |

| Other | 361 (21.1) | |

| Specialty | Internal medicine | 567 (32.7) |

| Family practice/general practice | 689 (39.7) | |

| Pediatrics | 477 (27.6) | |

| MSA | Large metro (over 200 000 population) | 1448 (83.5) |

| Small metro (under 200 000 population) | 62 (3.5) | |

| Nonmetro | 223 (13.0) | |

| Ability to provide high-quality care | Strongly disagree | 110 (6.4) |

| Disagree | 254 (14.7) | |

| Neutral | 43 (2.5) | |

| Agree | 658 (38.0) | |

| Strongly agree | 666 (38.4) | |

| IT use: number of function for clinical information access | No usage | 225 (12.9) |

| 1 | 259 (14.9) | |

| 2 | 468 (27.0) | |

| 3 | 436 (25.1) | |

| 4 | 345 (19.9) | |

| IT use: number of function for e-prescription | No usage | 699 (40.3) |

| 1 | 674 (38.9) | |

| 2 | 360 (20.8) | |

| IT use: number of function for information exchange | No usage | 410 (23.7) |

| 1 | 559 (32.2) | |

| 2 | 764 (44.1) | |

| Supportive/referral clinical resources constraints | High | 1516 (87.5) |

| Low | 217 (12.5) | |

| Patient out-of-pocket burden | High | 1064 (61.4) |

| Low | 669 (33.6) | |

| Policy restrictions on prescribing medication | High | 1151 (66.4) |

| Low | 582 (33.6) | |

| Patient-centered practice environment | Mean = 3.89 | SD = 0.02 |

Abbreviations: IT, information technology; SD, standard deviation.

an = 1733.

Approximately 38% of salaried primary care physicians were strongly confident that they provide high-quality care. The majority of physicians in the sample used some health IT, with 87.1% using it to access clinical information, 59.7% for e-prescribing, and 76.3% for information exchange. Physicians generally believed their practice environment was aligned with patient centeredness (mean = 3.89), yet also perceived several significant constraints to their practice, including the inability to refer patients for specialty services (87.5% reported many barriers). Over 60% of physicians also reported basing practice decisions on the patient’s financial burden and facing constraints on ordering prescriptions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios of Salaried Primary Care Physicians’ Confidence in Providing High-Quality Care.a

| Independent Variable | Reference Group | Adjusted Odds Ratio of Strong Confidence in Providing High-Quality Primary Care | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Patient-centered practice environmentb | 4.07c | 3.37 | 4.91 | |

| Health IT use | ||||

| Clinical information | No use | |||

| Use 1 function | 1.24 | 0.79 | 1.97 | |

| Use 2 functions | 1.49 | 0.97 | 2.30 | |

| Use 3 functions | 1.58d | 1.01 | 2.51 | |

| Use 4 functions | 2.01e | 1.19 | 3.39 | |

| E-prescriptions | No use | |||

| Use 1 function | 0.93 | 0.70 | 1.23 | |

| Use 2 functions | 0.61d | 0.42 | 0.90 | |

| Information exchange | No use | |||

| Use 1 function | 1.11 | 0.80 | 1.54 | |

| Use 2 functions | 1.08 | 0.77 | 1.53 | |

| High constraints affecting decisions | Low constraint | |||

| Patient out-of-pocket cost burden | 0.84 | 0.66 | 1.06 | |

| Supportive/referral clinical resources available | 0.49e | 0.30 | 0.78 | |

| Medication prescription restrictions | 1.21 | 0.94 | 1.56 | |

| Physician financial incentives | ||||

| Aligned with care quality/contentb | 1.11 | 1.00 | 1.24 | |

| Aligned with productivity/profitabilityb | 0.96 | 0.88 | 1.04 | |

| Physician and practice characteristics | ||||

| Age | ≤40 | |||

| 41-50 | 1.14 | 0.86 | 1.50 | |

| 51-60 | 1.09 | 0.80 | 1.50 | |

| Older than 61 | 1.01 | 0.65 | 1.55 | |

| Male gender | Female | 1.30d | 1.02 | 1.67 |

| Race | White | |||

| Other | 1.12 | 0.80 | 1.58 | |

| Black | 0.94 | 0.59 | 1.48 | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics | |||

| Internal medicine | 0.65d | 0.48 | 0.88 | |

| Family practice | 0.71 | 0.53 | 1.95 | |

| Practice type and size | Clinic/office 1-2 MDs | |||

| Clinic/office 3+ MDs | 1.08 | 0.71 | 1.65 | |

| HMO | 1.14 | 0.79 | 1.64 | |

| Medical school | 1.21 | 0.73 | 2.00 | |

| Hospital based | 0.93 | 0.59 | 1.45 | |

| Other | 1.28 | 0.88 | 1.86 | |

| Size of practice area | Large metro | 1.26 | 0.68 | 2.32 |

| Small metro | 0.78 | 0.55 | 1.11 | |

| Nonmetro | 0.78 | 0.56 | 1.08 | |

| Foreign MD degree | US degree | |||

| % patients with foreign languageb | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IT, information technology.

an = 1733.

bContinuous variable.

c P < .001.

d P < .05.

e P < .01.

Logistic regression results suggest that physicians practicing in a more patient-centered practice environment are more likely to report providing high-quality care (odds ratio [OR] = 4.07; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 3.37-4.91). When compared to physicians who did not use any IT to access clinical information, physicians who use 3 or 4 functions were more likely to perceive that they provide high-quality care (OR = 2.01; 95% CI = 1.19-3.39 for all 4 functions; OR = 1.58; 95% CI = 1.01-2.51 for 3 functions). A similar positive impact of IT use on physicians’ ability to provide high-quality of care was not found in e-prescribing or the exchange of clinical patient information. In fact, physicians who used both e-prescription functions were 39% less likely to be confident in providing high-quality care compared to those who engaged in no e-prescribing IT functions.

The physician financial incentive variables were not statistically significant, suggesting that salaried primary care physicians may not be sensitive to reimbursement incentives in providing high-quality care. Physicians who faced major constraints in support of their clinical decisions were less than half as likely to report providing high-quality care (OR = 0.49; 95% CI = 0.30-0.78). Among physician and practice characteristics, male physicians were 30% more likely than female physicians, and internists were 35% less likely than pediatricians, to believe that they provided high-quality care.

Discussion

Despite its documented benefits, a relatively small proportion of salaried primary care in the United States is delivered using a patient-centered approach.18-22 Greater adoption of a PCMH approach in primary care could lead to more emphasis on provider partnerships, patient preferences, and communication, resulting in increased quality of care.23 Physician decisions are guided legally and ethically by the best interests of their patients, so their perceptions of how certain factors influence their ability to provide high-quality care are likely to be strong predictors of whether they are interested in changing practice behaviors.

The impact of health IT on physicians’ confidence in providing quality of care was mixed in this study. The positive impact of IT use to access clinical information on quality primary care is consistent with previous literature.24,25 However, IT use for e-prescribing was negatively associated with high-quality primary care. Although e-prescribing could enhance medication safety,26 physicians have been critical of its usefulness in providing safety alerts27 and are also concerned about the required time commitment for computing tasks rather than spending time with patients.28 This may prompt physicians to believe that e-prescribing does not enhance, and in fact may distract from, their ability to provide quality care. Realizing the full practice benefits of e-prescribing in primary care may require careful attention in the transition to an e-prescribing system to ensure that it is perceived as complementing a primary care physicians’ workflow instead of generating more problems that adversely affect the physicians’ time or practice.28,29

Current health reform emphasizes the importance of patient information exchange among health-care providers and its role in improving patient safety and the quality of care.30 Lack of a significant related finding in this study may indicate that salaried primary care physicians perceived little advantage to engage in this or alternatively that exchange of patient information between primary care physicians and hospitals or specialists is limited31,32 due to lack of data standards and interoperable systems33 or possible physician resistance to changes in the care process.34,35 The significant findings for clinical IT access and lack of a comparable result for other IT functions might also indicate that physicians in this study may have been familiar with using health IT simply to access patient information, including laboratory test results and visit history, rather than exchanging patient information with other providers or e-prescribing.

Previous studies on health IT have generally been limited to just a few large health institutions and have focused on specific health outcome measures.12 This study relies on a national sample of physicians in different primary care practices and includes different measures of IT adoption and use as well as quality of care. Although we might expect physician age and practice setting to be associated with IT use, neither factor was estimated to have an independent impact even when each was included in the model separately to avoid possible correlation problems. Although IT adoption in primary care has increased during the last decade, recent data still indicate a lower use of health IT among primary care physicians.10,11 Our results have managerial implications for primary care practices planning to adopt or increase use of health IT systems. For example, access to clinical referral services was negatively associated with the perceived ability to provide high-quality care. Effective use of these resources is critical to implementing a PCMH model of primary care. This highlights the importance of aggressive and proactive attention by administrators to maximize access to these resources and ensure that physicians are trained in their use and understand how they contribute to both improving patient care and achieving the organization’s mission.36

Several data and design issues may limit generalization of this study’s results. First, Health maintenance organization (HMO) penetration in the health-care market was not controlled explicitly.37 Although areas with greater HMO enrollment may be more conducive to health IT use, the data did not permit inclusion of this factor. However, factors that may be indirectly related to HMO presence in markets, such as e-prescribing constraints and limitations in obtaining referral or clinical support services, were included in the empirical analysis. Although this study focused on IT usage behaviors regardless of the exact practice setting, there may have been a relationship between the type of practice setting and the availability of IT use. Similarly, primary care physicians who did not use health IT may have faced different practice policies or financial incentives compared to those who made greater use of IT. An indirect attempt was made to control for these possible impacts by including practice-specific structural and contextual factors. The duration of physician IT experience might also promote a more positive perception of the value of IT in delivery of quality care. Unfortunately, data on this factor were not available for this study. Given evidence of limited e-prescribing adoption by primary care physicians prior to 2008 and38 the years of these data, only a minimal impact on IT use would be expected. Finally, this study focused on salaried primary care physicians, so the results do not necessarily hold for nonsalaried physicians or those in other specialties.

Conclusion

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) includes a number of provisions to promote PCMH and adoption of health IT in order to reduce costs and improve care quality and patient outcomes.39 Since health IT is an important foundation of PCMH,40 patient-centered practices are more likely to have health IT in place to support care delivery. However, despite the potential to enhance the patent-centered delivery of primary care, simply making health IT available does not necessarily translate into physicians’ perceptions that it enhances the quality of care they provide. If physicians perceive that any dimension of health IT does not serve their (or their patient’s) interests or fails to contribute to providing high-quality care, they may tend not to use it optimally or simply refuse to use it at all.

The PCMH implementation significantly alters the care environment and practice of medicine by primary care physicians. It is crucial for health-care executives and managers to address challenges in PCMH transformation to ensure that physicians understand how to utilize health IT and recognize how it may improve health-care quality and outcomes instead of believing that it reduces their connection with patients and detracts from their ability to provide high-quality care. Providing more education for physicians on the benefits of PCMH practice and the effective use of health IT, including such strategies as identifying physician champions, involving physicians in decision on PCMH transition, and effective change management that enhances organizational learning, may facilitate effective implementation of patient-centered practice in primary care.

Salaried practice environments tend to be those that are larger where physicians may place a greater value on the availability of health IT. Even in these settings, the results of this study indicate that several dimensions of health IT did not positively impact the belief that using health IT strengthens their ability to provide high-quality care. Physicians in different settings may have even greater skepticism about the value of health IT insofar as it affects their potential for better patient relationships and the ability to provide quality care and may also dramatically increase their costs and time commitment to learn and use the technology. Given both the challenge for technology adoption in small primary care practices and the financial incentives to integrate more technology through Meaningful Use and policies or incentives included in the ACA, it is critical for health-care managers and policy makers to ensure that primary care physicians fully recognize and embrace the use of new technology to improve both the quality of care provided and the patient outcomes.

Author Biographies

JongDeuk Baek is an assistant professor at Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego State University.

Robert L. Seidman is an associate professor at Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego State University.

Appendix A

Original Survey Questions

| Provide High-Quality Care [Strongly disagree (1)–Strongly agree (5)] | |

| 1. | It is possible to provide high-quality care to my patients. |

| Patient Centered Practice Environment [Strongly disagree (1)–Strongly agree (5)] | |

| 1. | It is possible to maintain the kind of continuing relationships with patients over time that promote the delivery of high-quality care. |

| 2. | I have adequate time to spend with patients during typical office/patient visits. |

| 3. | I can make clinical decisions in the best interests of my patients without the possibility of reducing my income. |

| 4. | I have freedom to make clinical decisions that meet my patients’ needs. |

| Health IT Use | |

| Access to Clinical Information [No; Yes] | |

| 1. | In your practice, are computers or other forms of information technology used to obtain information about treatment alternatives or recommended guidelines? |

| 2. | In your practice, are computers or other forms of information technology used to generate reminders for you about preventive services? |

| 3. | In your practice, are computers or other forms of information technology used to access patient notes, medication lists, or problem lists? |

| 4. | In your practice, are computers or other forms of information technology used to obtain information on potential patient drug interactions with other drugs, allergies, and/or patient conditions? |

| Access to E-Prescribing [No; Yes] | |

| 1. | In your practice, are computers or other forms of information technology used to write prescriptions? |

| 2. | In your practice, are computers or other forms of information technology used to obtain information on formularies? |

| Exchange of Clinical Information [No; Yes] | |

| 1. | In your practice, are computers or other forms of information technology used for clinical data and image exchanges with other physicians? |

| 2. | In your practice, are computers or other forms of information technology used for clinical data and image exchanges with hospitals and laboratories? |

| Structural and Resource Constraints | |

| Availability of Clinical Support Resources [No; Yes] | |

| 1. | During the last 12 months, were you unable to obtain referrals to specialists of high quality? |

| 2. | During the last 12 months, were you unable to obtain nonemergency hospital admissions? |

| 3. | During the last 12 months, were you unable to obtain high-quality diagnostic imaging services? |

| 4. | During the last 12 months, were you unable to obtain high-quality outpatient mental health services? |

| Consider Patient Out-of-Pocket Burden [Never (1)–Always (5)] | |

| 1. | If there is uncertainty about a diagnosis, how often do you consider an insured patient's out-of pocket costs in deciding the types of tests to recommend? |

| 2. | If there is a choice between outpatient and inpatient care, how often do you consider an insured patient's out-of-pocket costs? |

| Policy restrictions on Prescribing Medication [Percent] | |

| 1. | What percentage of your patients have prescription coverage that includes the use of a formulary? |

| Physician Financial Incentives | |

| Financial Incentives Aligned with Care Content [Not important (1)–Very important (5)] | |

| 1. | How important are results of satisfaction surveys completed by your own patients in determining your compensation? |

| 2. | How important are specific measures of quality of care, such as rates of preventive care services for your patients in determining your compensation? |

| 3. | How important are results of practice profiles in determining your compensation? |

| Financial Incentives Aligned with Productivity/ Profitability [Not important (1)–Very important (5)] | |

| 1. | How important is your productivity in determining your compensation? |

| 2. | How important is overall practice performance? |

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Berwick D. What patient-centered care should mean: confessions of an extremist. Health Aff. 2009;28 (4):w555–w565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davis K, Abrams M, Stremikis K. How the affordable care act will strengthen the nation's primary care foundation. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26 (10):1201–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rittenhouse D, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Primary care and accountable care-two essential elements of delivery-system reform. N Engl J Med. 2009;361 (24):2301–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reid R, Fishman P, Yu O, et al. Patient-centered medical home demonstration: a prospective, quasi-experimental, before and after evaluation. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15 (9):e71–e87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Flottemesch TJ, Fontaine P, Asche SE, Solberg LI. Relationship of clinic medical home scores to health care costs. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34 (1):79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bechel D, Myers WA, Smith DG. Does patient-centered care pay off? Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2000;26 (7):400–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ponte P, Colin G, Conway JB, et al. Making patient-centered care more alive: achieving full integration of the patients’ perspective. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33 (2):82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thompson T, Brailer DJ. The Decade of Health Information Technology: Delivering Consumer-Centric and Information-Rich Health Care. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davis K, Doty M, Shea K, Stremikis K. Health information technology and physician perception of quality of care and satisfaction. Health Policy. 2009;90 (2-3):239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hsiao C, Hing E. Use and characteristics of Electronic health record systems among office-based physician practices: United States, 2001-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;(111):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schoen C, Osborn R, Doty MM, Squire D, Peugh J, Applebaum S. A survey of primary physicians in eleven countries, 2009: perspectives on care, costs, and experiences. Health Aff. 2009;28 (6):w1171–w1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, Maglione M, Mojica W, Roth Eea. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144 (10):742–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kemper P, Blumenthal D, Corrigan JM, et al. The design of the community tracking study: a longitudinal study of health system change and its effects on people. Inquiry. 1996;33 (2):195–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. American Medical Association. Socioeconomic Characteristics of Medical Practice. Chicago: Center for Health Policy Research; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centered consultations and outcomes in primary care: a review of literature. Pat Education Couns. 2002;48 (1):51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Council of Quality Assurance. Patient Centered Medical Home: Healthcare That Revolves Around You. National Council of Quality Assurance; 2014, Washington D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baek J, Xirasagar X, Stoskopf CH, Seidman RL. Physician-targeted financial incentives and primary care physicians’ self-reported ability to provide high quality primary care. J Prim Care Commun Health. 2013;4 (3):182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stewart M. Effective physician patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152 (9):1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kinnersley P, Scott N, Peters T, Harvey I. The patient-centeredness of consultations and outcomes in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49 (446):711–716. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Savage R, Armstrong D. Effect of a general practitioners’ consulting style on patient satisfaction: a controlled study. BMJ. 1990;301 (6758):968–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Health Care Quality Report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005:79–82, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Audet A, Davis K, Schoenbaum SC. Adoption of patient centered care practice by physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166 (7):754–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rosanthal T. The medical home: growing evidence to support a new approach to primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21 (5):427–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Linder J, Ma J, Bates DW, Middleton B, Stafford RS. Electronic health record use and the quality of ambulatory care in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167 (13):1400–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. DesRoches C, Campbell ER, Rao SR, et al. Electronic health records in ambulatory care—a national survey of physicians. N Engl J Med. 2008;359 (1 ):50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ammenwerth E, Schness-Inderst P, Machan C, Siebert U. The effect of electronic prescribing on medication errors and adverse drug events: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15 (5):585–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weingart S, Simchowitz B, Brouillard D, et al. Clinicians’ assessments of electronic medication safety alert in ambulatory care. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169 (1):1627–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hollingworth W, Devine EB, Hansen RN, et al. The impact of e-prescribing on prescriber and staff time in ambulatory care clinics: a time-motion study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14 (6):722–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jariwala K, Holmes ER, Banahan BF, McCaffrey DJ. Adoption of and experience with e-prescribing by primary care physicians. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2013;9 (1):120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marchibroda J, Bordenick JC. Emerging Trends and Issues in Health Information Exchange. Washington: eHealth Initiative; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians. JAMA. 2007;297 (8):831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. O’Malley A, Grossman JM, Cohen GR, Kemper NM, Pham HH. Are electronic medical records helpful for care coordination? Experiences of physician practices. J Gen Inter Med. 2010;25 (3):177–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Halamka J, Overhage M, Ricciardi L, Rishel W, Shirky C, Diamond C. Exchange health information: local distribution, national coordination. Health Aff. 2005;24 (5):1170–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Patel V, Abramson EL, Edwards A, Malhotra S, Kaushal R. Physicians’ potential use and preference related to health information exchange. Intl J Med Inform. 2011;80 (3):171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ross S, Schilling LM, Fernald DH, Davidson AJ, West DR. Health information exchange in small-to-medium sized family medicine practices: motivators, barriers, and potential facilitators of adoption. Intl J Med Inform. 2010;79 (2):123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nutting P, Crabtree B, Miller W, Stange K, Stewart E, Jean C. Transforming physician practice to patient-centered medical homes: lesson from the national demonstration project. Health Aff. 2011;30 (3):439–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hadley J, Mitchell JM, Sulmasy DP, Bloche MG. Perceived financial incentives, HMO market penetration, and physicians’ practice styles and satisfaction. Health Serv Res. 1999;34 (1):307–321. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gabriel M, Swain M. E-Prescribing Trends in the United States. Washington, DC: Institute for Health Technology Transformation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 111th Congress, 2009. –2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bates D, Bitton A. The future of health information technology in the patient-centered medical home. Health Aff. 2010;29 (4):614–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]