Abstract

Objectives:

To explore the public’s awareness of cancer symptoms and the barriers to seeking medical help among Omani adults attending primary care settings in Muscat governorate, the capital city of Oman.

Methods:

The Cancer Awareness Measure (CAM) questionnaire (translated into Arabic) was used to collect data from a total of 12 randomly selected local health centers (LHCs) in Muscat governorate, the capital city of Oman. Omani adults aged 18 years and above attending LHCs during the study period were invited to participate in the study. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 22) was used to analyze the data.

Results:

A total of 999 participants completed the CAM questionnaire from 1200 invitations (response rate = 83%). The overall recognition of common cancer symptoms was less than 50% except for an unexplained lump/swelling, which was 71%. Multinomial logistic regression showed that women recognized more cancer symptoms than men (odds ratio [OR] = 1.79; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.27-2.51), that more highly educated participations recognized more cancer symptoms than less educated participants (OR = 39; 95% CI: 0.23-0.69). The majority of participants (91.2%) agreed that the right time to seek medical help for possible cancer symptom was within 2 weeks. Multinomial logistic regression showed that women rather than men were more likely to perceive barriers to seeking medical help (OR = 2.10; 95% CI: 1.60-2.76). Also the less educated participants, rather than more educated, were more likely to perceive barriers to seeking medical help (OR = 2.17; 95% CI: 1.16-4.05).

Conclusion:

Levels of awareness of cancer symptoms are low in Oman. More national CAMs are needed in Oman to increase public knowledge of cancer symptoms. Also, more public awareness is needed to overcome the barriers to seeking timely medical help particularly among groups of women and the unmarried, widowed, divorced, or separated if delays in presentation are to be minimized.

Keywords: neoplasms, diagnosis, primary health care, adult, Oman

Introduction

Cancer is the leading cause of mortality in many countries around the world.1 The incidence of different types of cancer has increased in the past 20 years and is expected to rise further with an estimated 26 million new cancer cases and 17 million cancer deaths per annum by 2030.1,2 The majority of deaths from all types of cancer (70%) occur in low- and middle-income countries and are most likely because of poor awareness of cancer symptoms, delayed diagnosis, low availability of tests or screening programs, and limited access to standard treatment.3,4 Nonetheless, the majority of cancers occur as the result of potentially modifiable risk factors including smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, unhealthy diet (high fat, low fiber), obesity, lack of physical activity, sexually transmitted diseases, and urban air pollution.5

Certain types of cancer have high chance of cure if detected early and treated effectively.6 However, poor public knowledge of cancer symptoms and negative beliefs, such as “scared about what the doctor might find” and “worried about wasting the doctor’s time,” delays the seeking of medical help particularly if the symptoms are atypical in nature.7,8 Indeed, many early cancer symptoms may not be painful or interfere with functioning and may not be recognized as warning signs of cancer or trigger help-seeking behavior.9 Thus, it has been found that raising public awareness of the warning symptoms of cancer and encouraging prompt presentation could reduce patient-attributable delay in cancer diagnosis and decrease cancer mortality.10,11

Oman is a developing country located in the southeastern quarter of the Arabian Peninsula and covers a total land area of 309 500 km2. In 2010, the national census recorded a total population of 2.7 million, of which 1.9 million were Omanis.12 Approximately 35% of Omanis were aged below 15 years and only 3.5% were aged above 65 years (median age: 22 years).13 In 2010, approximately 21% of the total population resided in the capital city, Muscat, which is the most populated city in Oman.13 More than 75% of the disease burden in Oman is attributable to noncommunicable diseases, including cancer that has increased to a level similar to that in developed countries.14,15 Over the next 25 years, the elderly population in Oman will increase 6-fold, and the urbanization rate is expected to reach 86% with noncommunicable diseases, the leading cause of death.14

In Oman, cancer has been regarded as the second leading cause of death and the third most likely cause of loss of disability-adjusted life years.14 Data from the National Cancer Registry show that approximately 900 new cases of cancer are reported annually, and the annual age-adjusted incidence of cancer ranges from 70 to 110 per 100 000 population.15,16 In the 9-year period (1998-2006), stomach cancer, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and leukemia were the most common cancers in Omani men. Lung cancer was the fourth, possibly because smoking was uncommon in Oman before 1970; breast, thyroid, and cervical cancers were the most common cancers in Omani women.17

Even though up-to-date treatments are available, the majority of patients with cancer in Oman tend to present at advanced stages, at a younger age, and with low survival rates.18 Furthermore, there are no screening programs for cancer except for breast cancer for which a program was introduced in 2010.19 There are also other cultural factors that might contribute to delay in cancer diagnosis in Oman.20 The aim of this study was to identify the level of awareness of early cancer symptoms and the timeliness of seeking medical help among Omani adults attending primary care settings in Muscat governorate.

Methods

Tool Used to Measure Cancer Awareness

The Cancer Awareness Measure (CAM) questionnaire is a validated standardized measurement for cancer awareness in the general population.21 The questionnaire includes 9 possible warning symptoms of cancer that were reported either in the European Code against Cancer or by the major cancer organizations. The questionnaire measures awareness of warning signs, anticipated time before seeking medical help, and perceived barriers to presentation for 10 common warning signs. The warning signs are persistence changes in bowel or bladder habits, a sore that does not heal, unexplained bleeding, unexplained lump or swelling, an obvious change in a wart or mole, persistent unexplained pain, persistent cough or hoarseness, difficulty in swallowing, unexplained weight loss, and loss of appetite.

The barriers to seeking medical help were further categorized into emotional, practical, and service barriers. The reliability (Cronbach’s α = .70), validity (>78%), and test–retest reliability (r2 = .60) of CAM were found to be high, and it has been used in several studies around the world.8,21,22

The CAM was translated from English to Arabic and then back-translated into English by several people proficient in both languages. Before embarking on data collection, a pilot study for the first 30 respondents was conducted to assess reliability of the Arabic version CAM and the clarity of the questions. Based on the standardized items, the Cronbach’s α of the Arabic version of the CAM from the pilot study was .817.

Recruitment of Local Health Centers

Primary health care is considered the first port of entry to all levels of health care in Oman. Through the Ministry of Health, the Omani government funds and provides free health-care services to all Omanis and non-Omanis working in the government sector. There are a total of 27 local health centers (LHCs) in Muscat governorate, each of which provides primary health-care services to the population in their specific catchment area.13 Of the 27 LHCs, 12 were randomly selected for inclusion in the study, based on the assumption that the attending participants of those 12 LHCs were no different to those attending the unselected LHCs. Also, the calculated sample size could be achieved without involving more LHCs. The Directorate General of Health Services in Muscat governorate was contacted for the permission to involve the selected LHCs in the study.

Recruitment of Participants

This cross-sectional study was carried out from September to October 2015. One nurse from each LHC was included in this study and was trained to distribute and collect the questionnaires from the study participants. They were also trained to administer the questionnaire to illiterate participants. All adult patients and attendees (age ≥ 18 years) attending the selected LHCs during the study period were invited to participate in the study. Very sick patients and emergency cases were excluded. An explanation of the study was given to the participants by the trained nurses. Participants who agreed to take part in the study and who could read and write were asked to sign a consent form and to complete the questionnaire by themselves while waiting to see the doctors for consultation. For illiterate participants, the questionnaire was administered by the trained nurses.

Statistical Methods

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22 (IBM Corp, Chicago, Illinois). Descriptive statistics were calculated for sociodemographics of the participants and cumulative score for the recognition of cancer symptoms and reported barriers. The χ2 test was used to find associations between the demographic factors and cancer symptoms and reported barriers nominal variables. Multinomial regression analysis was done for adjusting the factors. This study was approved by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences at Sultan Qaboos University (MREC #794).

Results

A total of 999 participants participated in the study from 1200 invited (response rate = 83%). There were 495 (49.5%) male and 504 (50.5%) female participants; their ages ranged from 18 to 80 years. The overall mean age of participants was 33.4 ± 9.6. The majority of participants (63.1%) completed school education (primary, intermediate, or secondary education). A small subset of the participants had a family history of cancer (17.9%; Table 1).

Table 1.

The Distribution of Sociodemographic Variables of the Participants in This Study.

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 495 (49.5) |

| Female | 504 (50.5) |

| Age, years | |

| 18-30 | 459 (45.9) |

| 31-50 | 492 (49.2) |

| >50 | 48 (4.8) |

| Education | |

| No formal education | 58 (5.8) |

| School education | 630 (63.1) |

| University and PG | 311 (31.1) |

| Social status | |

| Single | 189 (18.9) |

| Married | 772 (77.3) |

| Divorced/widow | 38 (3.8) |

| Family history of cancer | |

| Yes | 174 (17.9) |

| No | 797 (82.1) |

Abbreviation: PG, postgraduate.

Recognition of Symptoms

The median overall recognition of cancer symptoms score was 40% and was higher in women (40%) compared to men (30%). The median recognition score was 40% in younger and middle-aged groups and 35% in the elderly age groups. University and postgraduate participants were more likely to recognize cancer symptoms (50%), followed by participants who were school educated (40%) and participants with no formal education (25%).

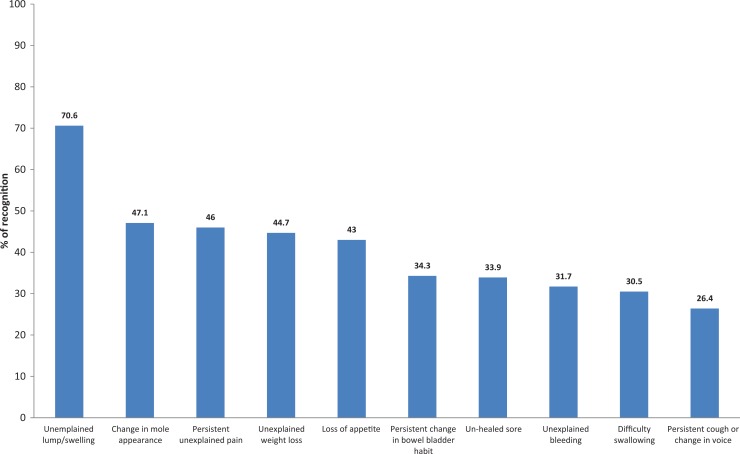

The most frequently recognized cancer symptom was “unexplained lump/swelling” (70.6%) followed by “change in mole appearance” (47.1%), “persistence unexplained pain” (46%), “unexplained weight loss” (44.7%), “loss of appetite” (43%), “persistence change in bowel or bladder habit” (34.3%), “unhealed sore” (33.9%), “unexplained bleeding” (31.7%), “difficulty in swallowing” (30.5%), and “persistent cough or change in voice” (26.4%; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage distribution of recognition of cancer symptoms among the participants in this study.

There is a considerable, strong association with the recognizing of cancer symptoms and perceived barriers seeking medical help by the sociodemographic variables. In the multinomial logistic regression model, gender and education level were significantly associated with recognition of cancer symptoms (Table 2). Women were more likely than men to be recognized the following cancer symptoms: “unexplained weight loss” (odds ratio [OR] = 1.79; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.27-2.51), “loss of appetite” (OR = 1.95; 95% CI: 1.36-2.79), and “change in bowel or bladder habit” (OR = 1.55; 95% CI: 1.08-2.23).

Table 2.

Recognition of Cancer Symptoms by Sociodemographics.a

| Variables | Recognition of Symptoms, OR (95% CI) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unexplained Lump/Swelling | Unexplained Persistent Pain | Unexplained Bleeding | Persistent Cough/Hoarseness | Difficulty in Swallowing | Change in Appearance of Mole | Sore that Does Not Heal | Unexplained Weight Loss | Loss of Appetite | Change in Bowel/Bladder Habit | |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Men | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Women | 1.52 (0.98-2.36) | 1.29 (0.93-1.79) | 1.27 (0.91-1.78) | 1.16 (0.83-1.62) | 1.14 (0.81-1.60) | 1.34 (0.92-1.93) | 1.33 (0.94-1.90) | 1.79b (1.27-2.51) | 1.95c (1.36-2.79) | 1.55b (1.08-2.23) |

| Age group | ||||||||||

| 18-30 | 0.60 (0.19-1.93) | 1.40 (0.62-3.14) | 0.87 (0.38-2.0) | 1.13 (0.50-2.54) | 0.65 (0.28-1.54) | 0.93 (0.36-2.38) | 0.83 (0.34-2.03) | 1.68 (0.72-3.92) | 1.09 (0.47-2.55) | 1.84 (0.78-4.33) |

| 31-50 | 0.52 (0.17-1.62) | 1.19 (0.54-2.63) | 0.84 (0.37-1.89) | 1.31 (0.59-2.89) | 0.77 (0.33-1.80) | 0.81 (0.32-2.06) | 0.93 (0.39-2.25) | 1.16 (0.51-2.65) | 0.97 (0.42-2.22) | 1.95 (0.85-4.50) |

| 50+ | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| No formal | 0.31b (0.11-0.84) | 0.53 (0.24 -1.14) | 0.90 (0.39-2.08) | 1.08 (0.51-2.29) | 0.61 (0.27-1.39) | 0.69 (0.27-1.79) | 0.46 (0.20-1.09) | 0.75 (0.34-1.65) | 0.54 (0.23-1.28) | 0.55 (0.24-1.26) |

| School | 0.39b (0.23-0.69) | 0.50c (0.35-0.72) | 0.55b (0.39-0.79) | 0.98 (0.69-1.40) | 0.67b (0.47-0.96) | 0.54b (0.35-0.81) | 0.69 (0.47-1.00) | 0.99 (0.69-1.41) | 0.73 (0.50-1.08) | 0.83 (0.57-1.23) |

| University and PG | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Single | 2.55 (0.88-7.42) | 0.98 (0.37-2.58) | 0.30 (0.09-1.02) | 0.60 (0.23-1.60) | 0.97 (0.34-2.78) | 0.46 (0.12-1.70) | 0.67 (0.21-2.06) | 0.41 (0.14-1.22) | 1.02 (0.35-3.01) | 0.75 (0.24-2.34) |

| Married | 2.09 (0.84-5.18) | 0.90 (0.37-2.20) | 0.34 (0.11-1.08) | 0.64 (0.26-1.59) | 1.06 (0.40-2.86) | 0.47 (0.13-1.64) | 0.54 (0.19-1.57) | 0.56 (0.20-1.55) | 1.00 (0.37-2.72) | 0.96 (0.33-2.77) |

| Others | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PG, postgraduate.

aN = 999.

b P < .05.

c P < .001.

Participants with no formal education demonstrated less overall recognition of cancer symptoms compared to university and postgraduate participants (OR = 0.31; 95% CI: 0.11-0.84). Participants with school education showed less overall recognition of cancer symptoms compared to university and postgraduate participants (OR = 0.39; 95% CI: 0.23-0.69).

Compared to university and postgraduate participants, those with school education only demonstrated less awareness of a possible relationship to cancer for the following symptoms—“unexplained persistent pain” (OR = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.35-0.72), “difficulty in swallowing” (OR=0.67; CI: 0.47-0.96), and “change in appearance of mole” (OR = 0.54; CI: 0.35-0.81).

Perceived Barriers to Seeking Medical Help

The majority of participants (91.2%) agreed that the right time to see a doctor is within 2 weeks of noticing a possible cancer symptom. Of all the possible cancer symptoms, most participants would seek medical advice if they had unexplained bleeding (89.6%); only 59.7% of participants would go see a doctor due to unexplained weight loss (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participants’ Expected Time to Consult a Doctor in Response to Possible Symptoms of Cancer.

| Variables | Within 2 Weeks (%) | Within 1 Month (%) | Within 6 Months (%) | After 6 Months=(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to see a doctor if noticed possible symptoms of cancer | 895 (91.2) | 57 (5.8) | 15 (1.5) | 14 (1.4) |

| Unexplained bleeding | 881 (89.6) | 46 (4.7) | 19 (1.9) | 37 (3.8) |

| Unexplained lump or swelling | 868 (87.9) | 61 (6.2) | 29 (2.9) | 29 (2.9) |

| Persistent unexplained pain | 834 (85.2) | 81 (8.3) | 30 (3.1) | 34 (3.5) |

| Persistent difficulty swallowing | 811 (84.2) | 95 (9.9) | 22 (2.3) | 35 (3.6) |

| Sore that does not heal | 786 (80.9) | 108 (11.1) | 39 (4.0) | 39 (4.0) |

| Persistent cough or hoarseness | 792 (80.7) | 116 (11.8) | 32 (3.3) | 42 (4.3) |

| Change in the appearance of a mole | 765 (76.6) | 115 (11.5) | 49 (5.0) | 53 (5.4) |

| Persistent change in bowel or bladder habits | 741 (75.2) | 113 (11.5) | 57 (5.8) | 75 (7.6) |

| Loss of appetite | 631 (64.5) | 178 (18.2) | 81 (8.3) | 88 (9.0) |

| Unexplained weight loss | 586 (59.7) | 167 (16.7) | 110 (11.2) | 118 (12.0) |

There were more perceived barriers to seeking medical help in women (50%) compared to men (40%) and in elderly participants (60%) compared to the young or middle-aged (40%). Participants with no formal education reported more perceived barriers (60%) compared to educated participants (40%). Unmarried, widowed, divorced, and separated participants reported more perceived barriers (50%) compared to married participants (40%).

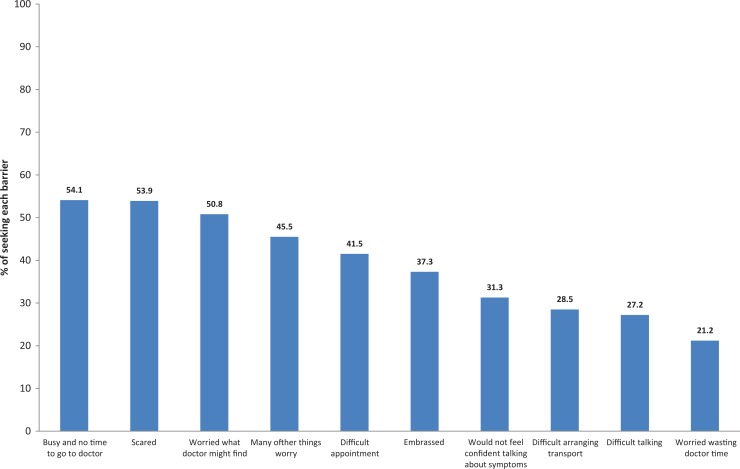

More than half of participants reported barriers such as “busy/don’t have time to go to the doctor” (54.1%), “scared” (53.9%), “worried what the doctor might find” (50.8%), “many other things to worry about” (45.5%), “difficult to make an appointment” (41.5), “embarrassed” (37.3%), “wouldn’t feel confident talking about symptoms” (31.3%), “difficult to arrange transport” (28.5%), “difficult talking to doctor” (27.2%), and “worried about wasting the doctor’s time” (21.2%; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage distribution of reported barriers.

A multinomial logistic regression model showed that barriers to seeking medical help were significantly associated with gender, education level, and marital status of participants (Table 4). Women were more likely than men to report perceived barriers to seek medical help for the following reasons—“scared” (OR = 2.10; 95% CI: 1.60-2.76), “difficult to arrange transport” (OR = 2.02; 95% CI: 1.49-2.73), and “worried what the doctor might find” (OR = 1.47; CI: 1.11-1.93).

Table 4.

Participants Perception of Barriers to Presentation by Sociodemographics.a

| Variables | Barriers OR (95% CI) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embarrassed | Scared | Worried Wasting Doctor Time | Difficult Talking to Doctor | Difficult to Make an Appointment | Busy and No Time to Go to Doctor | Many Other Things to Worry | Difficult to Arrange Transport | Worried What Doctor Might Find | Would Not Feel Confident Talking About Symptoms | |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Men | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Women | 1.27 (0.97-1.67) | 2.10b (1.60-2.76) | 0.88 (0.64-1.22) | 1.07 (0.79-1.44) | 0.91 (0.69-1.20) | 1.15 (0.87-1.51) | 1.08 (0.82-1.42) | 2.02b (1.49-2.73) | 1.47c (1.11-1.93) | 1.04 (0.79-1.38) |

| Age group | ||||||||||

| 18-30 | 0.91 (0.47-1.74) | 0.84 (0.43-1.65) | 0.70 (0.34-0.14) | 0.70 (0.35-1.38) | 0.78 (0.39-1.53) | 1.15 (0.57-2.31) | 0.81 (0.41-1.64) | 0.96 (0.46-1.99) | 0.90 (0.45-1.82) | 0.74 (0.38-1.45) |

| 31-50 | 0.72 (0.38-1.37) | 0.61 (0.31-1.17) | 0.60 (0.30-1.22) | 0.65 (0.33-1.27) | 0.90 (0.46-1.76) | 1.09 (0.55-2.16) | 0.72 (0.36-1.43) | 0.73 (0.36-1.51) | 0.63 (0.32-1.25) | 0.67 (0.35-1.30) |

| 50+ | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| No formal | 2.17c (1.16-4.05) | 0.62 (0.33-1.15) | 3.32c (1.67-6.64) | 2.81c (1.47-5.41) | 1.41 (0.73-2.71) | 0.97 (0.51-1.85) | 1.47 (0.76-2.86) | 4.0b (2.06-7.80) | 1.62 (0.83-3.17) | 1.33 (0.69-2.56) |

| School | 1.58c (1.17-2.12) | 1.09 (0.81-1.45) | 1.83c (1.27-2.65) | 2.11b (1.50-2.97) | 1.28 (0.96-1.72) | 0.82 (0.61-1.10) | 0.85 (0.64-1.13) | 2.20b (1.57-3.09) | 1.03 (0.77-1.38) | 1.30 (0.96-1.76) |

| University and PG | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Single | 1.42 (0.63-3.17) | 0.65 (0.28-1.49) | 0.52 (0.22-1.21) | 0.71 (0.31-1.62) | 0.54 (0.23-1.25) | 0.36 (0.13-1.02) | 0.39c (0.16-0.98) | 0.45 (0.19-1.08) | 0.72 (0.30-1.72) | 0.79 (0.36-1.73) |

| Married | 0.96 (0.45-2.02) | 0.62 (0.28-1.35) | 0.56 (0.26-1.20) | 0.53 (0.25-1.13) | 0.07 (0.22-1.06) | 0.25 (0.10-0.68) | 0.31c (0.13-0.74) | 0.36c (0.16-0.81) | 0.63 (0.28-1.41) | 0.63 (0.31-1.31) |

| Others | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PG, postgraduate.

aN = 999.

b P < .001.

c P < .05.

Participants with no formal education were more likely than university educated and postgraduate participants to perceive the following as barriers to seek medical help—“embarrassed” (OR = 2.17; 95% CI: 1.16-4.05), “worried about wasting doctor time” (OR = 3.32; 95% CI: 1.67-6.64), “difficult to talk to the doctor” (OR = 2.81; 95% CI: 1.47-5.41), and “difficult to arrange transport” (OR = 4.0; 95% CI: 2.06-7.80). Participants in the school-educated group were more likely than university-educated and postgraduate participants to perceive the following as barriers to seek medical help—“embarrassed” (OR = 1.58; 95% CI: 1.17-2.12), “worried about wasting doctor time” (OR = 1.83; 95% CI: 1.27-2.65), “difficult to talk to the doctor” (OR = 2.11; 95% CI: 1.50-2.97), and “difficult to arrange transport” (OR = 2.20; 95% CI: 1.57-3.09).

Single participants were less likely than divorced or separated participants in reporting “too many other things to worry about” (OR = 0.39; 95% CI: 0.16-0.98). Also, married participants were less likely than divorced or separated participants to report “too many other things to worry about” (OR = 0.31; 95% CI: 0.13-0.74) and “difficult arranging transport” (OR = 0.36; 95% CI: 0.16-0.81).

Discussion

This study explored public awareness of common cancer symptoms and the timeliness of seeking medical help by recognizing the symptoms. The majority of participants in this study were unaware of the common cancer symptoms. The previous studies conducted in developed and developing countries showed similar findings of poor public awareness of cancer symptoms.7,23,24

National campaigns conducted in the developed countries to increase public awareness of cancer symptoms have been effective. For example, in the United Kingdom, national bowel and lung cancer campaigns conducted between 2011 and 2012 have increased the public’s awareness that a persistent cough, hoarseness, and a change in bowel/bladder habits were possible cancer symptoms and should prompt individuals to seek medical help.24

The most frequently recognized cancer symptom in our study was “unexplained lump or swelling” and the least frequently recognized was “persistent cough or change in voice.” This supports the findings from a UK study that also showed that “unexplained lump or swelling” was the most recognized cancer symptom.24 The higher levels of recognition of “unexplained lump or swelling” as a possible cancer symptom might reflect the successful work of the Oman Cancer Association over the past several years to promote community awareness of breast cancer and the importance of seeking medical help if possible cancer symptoms are noticed.25

Symptoms such as a lump or pain, or symptoms that interfere with daily activities are more easily recognized by the general public as reasons to seek medical help at early stage.22 Other cancer symptoms that are not perceived as serious (eg, cough, change in voice, change of bowel habit, fatigue, weight loss, and loss of appetite) are more likely to be associated with a delay in seeking medical help.26

The lower recognition among men compared to women, of some vague cancer symptoms such as “unexplained weight loss,” “loss of appetite,” and “change in bowel or bladder habit,” in this study is supported by findings from previous studies.27,28 Women are usually more frequently in contact with health-care services compared to men as a result of pregnancy, family planning, childcare, hormone replacement therapy, and cancer screening. Greater contact with health-care services increases health-related knowledge and encourages women to have more preventive and protective behaviors than men, including cancer detection.29 Also the male gender role may conflict with healthy behavior, including the perception of being less at risk of cancer, and this could delay seeking medical help at an appropriate time.29,30

The more highly educated participants in this study were more aware of cancer symptoms than the less educated participants. A UK study showed that people with a higher level of education demonstrated greater knowledge of the early symptoms of colorectal and breast cancer.31Also, other studies conducted in the United States showed that 16 years of education could decrease colorectal cancer death rates by 2.4% and that people with less than a high school education had greater incidence of lung cancer than more educated people.32,33 This would indicate that educational attainment is an important factor in increasing the awareness of cancer symptoms and its predisposing risks such as smoking, physical activity, obesity, and diet, and might also increase the use of hormone replacement therapy and attending cancer screening programs.34

In this study, it was noted that elderly participants were less aware of cancer symptoms compared to the younger group. This might be related to the fact that the younger group would have probably attained a higher education level than the older group, as formal education in Oman has only been available for past 50 years.

The majority of participants agreed that the right time to see a doctor was within 2 weeks of noting possible cancer symptoms, particularly for obvious symptoms rather than vague ones. For example, it has been found that patients with breast cancer are more likely than patients with prostate and rectal cancer to seek medical help.26 As mentioned earlier, knowledge of symptoms of cancer is a prerequisite for the correct help-seeking response.35 The more that the individual recognizes a specific symptom as serious, the more likely they are to engage in prompt help-seeking behavior and disclose their symptoms to another person.36

Across all the participants in this study, the most common practical barrier to seeking medical help was “too busy to go to the doctor,” and the most common emotional barriers were “scared” and “worried about what the doctor might find” all of which were also supported with findings from previous studies conducted in the United Kingdom.22,37 Women were more likely than men to perceive “being scared” and “worried about what the doctor might find” as barriers in seeking early medical help in this study, which could lead to delay in the diagnosis. These women identified fear of embarrassment (the feeling that symptoms were trivial or that symptoms affected a sensitive body area) or fears of the consequent diagnosis and treatment (pain, suffering, and death) as the commonest barrier.9,38

As in the United Kingdom, women in Oman felt discomfort and embarrassment at exploring cancer symptoms were worried about side effects of treatments (surgery, chemotherapy) or believed that there was no cure for cancer, which may delay their cancer diagnosis.20 Indeed, a recent study conducted in Oman showed that breast cancer tended to present at a more advanced stage and at a younger age than in women in the Western world.39 In addition to a lower awareness of cancer symptoms, there might also be other cultural barriers for women in seeking medical help or accessing specialized units in Oman.20,39 Some of them travel overseas for diagnosis to seek other treatment modalities and maintain privacy from “cancer stigma,” all of which could delay a cancer diagnosis.20

The finding that elderly, widowed, divorced, separated, and less educated participants encountered more emotional barriers (“embarrassed” and “too many other things to worry about”) and practical barriers (“difficult to talk to the doctor” and “difficult to arrange transport”) in seeking medical help than their counterparts identifies these particular individuals as more likely to face a delay in cancer diagnosis. The majority of elderly patients in Oman are also less educated, which means they are at an even higher risk of delay in diagnosis. Previous studies conducted in the United States of America and Morocco showed that unmarried, separated, widowed, and divorced individuals presented with later stages of cancer at the time of diagnosis, with consequently poor prognoses.40,41,42 Indeed, single, widowed, or separated individuals might be more at risk for practical and emotional barriers due to unavailability of transport and presence of coexisting psychosocial difficulties.

This study current has limitations. It was conducted only in Muscat governorate, the capital city of Oman, which could affect the generalizability of the findings. However, the majority of people residing in Muscat are originally from other regions of Oman, and therefore, the generalizability of findings might not be a major issue. A larger national study with recruitment from all regions of Oman is needed for better representative sampling. Also, although the nurses in this study were trained to be neutral when surveying illiterate patients, there could have been a disparity in the meaning of statements from items of the questionnaire between the literate and illiterate respondents. Finally, we did not use the open-ended CAM questionnaire, but we believe this should not affect the findings of the study.

Conclusion

This study confirmed that the recognition of common cancer symptoms was low among the majority of Omani people attending a primary health-care setting. Also, there were several emotional and practical barriers to seeking early medical help for possible cancer symptoms, particularly among women—the less educated and unmarried, widowed, divorced, or separated individuals. Thus, a number of initiatives and programs aiming to raise symptom awareness and promote early presentation are needed in Oman. More educational activities in the community are needed to increase public awareness of cancer symptoms and encourage seeking early medical help, particularly for vulnerable groups such as widowed or separated women. Using media such as TV broadcasts, life lectures, seminars, and rapidly the expanding social media channels could improve cancer awareness among adolescents. Curriculum-based health education regarding the prevention of cancer and school visits by nurses and health educators could increase students’ awareness of cancer symptoms. Future research is needed in Oman to explore the underlying causes of the emotional and practical barriers that interfere with seeking early medical help, particularly among women—the single, widowed, divorced, separated, and in the elderly individuals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants and the Directorate General of Health Services of Muscat governorate for allowing this study to take part in the local health centers. The authors would also like to thank the College of Medicine and Health Sciences at Sultan Qaboos University, Oman, for sponsoring this research.

Author Biographies

Mohammed Al-Azri is an associate professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University. His research interests are cancer in primary health care and continuity of care, Oman.

Aziza Al-Maskari and Salma Al-Matroushi are family physicians, Ministry of Health, Oman.

Huda Al-Awisi is head of nursing research, Directorate of Nursing, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Oman.

Robin Davidson is consultant in the Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University.

Sathiya Murthi Panchatcharam is statistical specialist, Oman Medical Specialty Board, Oman.

Abdullah Al-Maniri is an epidemiologists and medical statistician. He is also the director of research in Oman Medical Specialty Board.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Dean’s Fund, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Cancer—Fact sheet. 2015. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/. Published 2010. Updated 2015. Accessed June 20, 2016.

- 2. Babu GR, Lakshmi SB, Thiyagarajan JA. Epidemiological correlates of breast cancer in South India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(9):5077–5083. doi:10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.9.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Norwati D, Harmy MY, Norhayati MN, Amry AR. Colorectal cancer screening practices of primary care providers: results of a national survey in Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(6):2901–2904. doi:10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.6.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moore MA, Sangrajrang S, Bray F. Asian Cancer Registry Forum 2014-Regional Cooperation for Cancer Registration: Priorities and Challenges. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(5):1891–1894. doi:10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.5.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Danaei G, Vander Hoorn S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M; Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group (Cancers). Causes of cancer in the world: comparative risk assessment of nine behavioural and environmental risk factors. Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1784–1793. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harford JB. Breast-cancer early detection in low-income and middle-income countries: do what you can versus one size fits all. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(3):306–312. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70273-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ravichandran K, Mohamed G, Al-Hamdan NA. Public knowledge on cancer and its determinants among Saudis in the Riyadh Region of Saudi Arabia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(5):1175–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Forbes LJ, Simon AE, Warburton F, et al. Differences in cancer awareness and beliefs between Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): do they contribute to differences in cancer survival? Br J Cancer. 2013;108(2):292–300. doi:10.1038/bjc.2012.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith LK, Pope C, Botha JL. Patients’ help-seeking experiences and delay in cancer presentation: a qualitative synthesis. Lancet. 2003;366(9488):825–831. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. MacDonald S, Macleod U, Campbell NC, Weller D, Mitchell E. Systematic review of factors influencing patient and practitioner delay in diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(9):1272–1280. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simon AE, Waller J, Robb K, Wardle J. Patient delay in presentation of possible cancer symptoms: the contribution of knowledge and attitudes in a population sample from the United Kingdom. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(9):2272–2277. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ministry of National Economy. Oman census summary. 2010. http://85.154.248.117/MONE2010/. Accessed June 20, 2016.

- 13. Directorate General Health Services of Muscat, Ministry of Health. www.moh.gov.om/en/web/directorate-general-health-services-muscat/facilities. Published 2010. Update 2016. Accessed June 20, 2016.

- 14. Al-Lawati JA, Mabry R, Mohammed AJ. Addressing the threat of chronic diseases in Oman. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(3):A99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rahim HF, Sibai A, Khader Y, et al. Non-communicable diseases in the Arab world. Lancet. 2014;383(9941):356–367. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization. Country cooperation strategy for WHO and Oman 2010-2015. 2010. http://www.who.int/countryfocus/cooperation_strategy/ccs_omn_en.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2016.

- 17. Nooyi SC, Al-Lawati JA. Cancer incidence in Oman, 1998-2006. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(7):1735–1738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kumar S, Burney I, Al-Ajmi A, Al-Moundhri M. Changing trends of breast cancer survival in Sultanate of Oman. J Oncol. 2011;2011:316243 doi:10.1155/2011/316243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ministry of Health. Early Detection & Screening for Breast Cancer-Operational Guidelines. 1st ed Oman: Department of Family & Community Health, Directorate General of Health Affair, Ministry of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Al-Azri M, Al-Awisi H, Al-Rasbi S, et al. Psychosocial impact of breast cancer diagnosis among Omani women. Oman Med J. 2014;29(6):437–444. doi:10.5001/omj.2014.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stubbings S, Robb K, Waller J, et al. Development of a measurement tool to assess public awareness of cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(suppl 2):S13–S17. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Robb K, Stubbings S, Ramirez A, Macleod U, Austoker J, Waller J. Public awareness of cancer in Britain: a population-based survey of adults. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(suppl 2):S18–S23. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hashim SM, Fah TS, Omar K, et al. Knowledge of colorectal cancer among patients presenting with rectal bleeding and its association with delay in seeking medical advice. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(8):2007–2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Power E, Wardle J. Change in public awareness of symptoms and perceived barriers to seeing a doctor following Be Clear on Cancer campaigns in England. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(suppl 1):S22–S26. doi:10.1038/bjc.2015.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oman Cancer Association. http://www.oca.om/en/. Updated 2016. Accessed June 20, 2016.

- 26. Forbes LJ, Warburton F, Richards MA, Ramirez AJ. Risk factors for delay in symptomatic presentation: a survey of cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(3):581–588. doi:10.1038/bjc.2014.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Adlard JW, Hume MJ. Cancer knowledge of the general public in the United Kingdom: survey in a primary care setting and review of the literature. Clin Oncol. 2003;15(4):174–180. doi:10.1016/S0936-6555(02)00416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moffat J, Bentley A, Ironmonger L, Boughey A, Radford G, Duffy S. The impact of national cancer awareness campaigns for bowel and lung cancer symptoms on sociodemographic inequalities in immediate key symptom awareness and GP attendances. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(suppl 1):S14–S21. doi:10.1038/bjc.2015.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Evans RE, Brotherstone H, Miles A, Wardle J. Gender differences in early detection of cancer. J Mens Health Gend. 2005;2(2):209–217. doi:10.1016/j.jmhg.2004.12.012. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Katz RC, Meyers K, Walls J. Cancer awareness and self-examination practices in young men and women. J Behav Med. 1995;18(4):377–384. doi:10.1007/BF01857661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McCaffery K, Wardle J, Waller J. Knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions in relation to the early detection of colorectal cancer in the United Kingdom. Prev Med. 2003;36(5):525–535. doi:10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kinsey T, Jemal A, Liff J, Ward E, Thun M. Secular trends in mortality from common cancers in the United States by educational attainment, 1993-2001. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(14):1003–1012. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Miller BA, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status on cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis: selected findings from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results: National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(4):417–435. doi:10.1007/s10552-008-9256-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Albano JD, Ward E, Jemal A, et al. Cancer mortality in the United States by education level and race. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(18):1384–1394. doi:10.1093/jnci/djm127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Macleod U, Mitchell ED, Burgess C, MacDonald S, Ramirez AJ. Risk factors for delayed presentation and referral of symptomatic cancer: evidence for common cancers. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(suppl 2):S92–S101. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Quaife SL, Forbes LJ, Ramirez AJ, et al. Recognition of cancer warning signs and anticipated delay in help-seeking in a population sample of adults in the UK. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(1):12–18. doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hvidberg L, Wulff CN, Pedersen AF, Vedsted P. Barriers to healthcare seeking, beliefs about cancer and the role of socio-economic position. A Danish population-based study. Prev Med. 2015;71:107–113. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bish A, Ramirez A, Burgess C, Hunter M. Understanding why women delay in seeking help for breast cancer symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58(4):321–326. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Al-Moundhri M, Al-Bahrani B, Pervez I, et al. The outcome of treatment of breast cancer in a developing country–Oman. Breast. 2004;13(2):139–145. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saghari S, Ghamsary M, Marie-Mitchell A, Oda K, Morgan JW. Sociodemographic predictors of delayed- versus early-stage cervical cancer in California. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(4):250–255. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Berraho M, Obtel M, Bendahhou K, et al. Sociodemographic factors and delay in the diagnosis of cervical cancer in Morocco. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;12:14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Greenberg MT, Weissberg RP, O’Brien MU, et al. Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. Am Psychol. 2003;58(6-7):466–474. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]