Abstract

Objective

To examine the trajectories of responses to acupuncture treatment for menopausal vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and the characteristics of women in each trajectory.

Methods

209 perimenopausal and postmenopausal women aged 45-60 years experiencing ≥4 VMS per day were recruited and randomized to receive up to 20 acupuncture treatments within 6 months or to a waitlist control group. The primary outcome was percent change from baseline in the mean daily VMS frequency. Finite mixture modeling was used to identify patterns of percent change in weekly VMS frequencies over the first 8 weeks. The Freeman-Holton test and ANOVA were used to compare characteristics of women in different trajectories.

Results

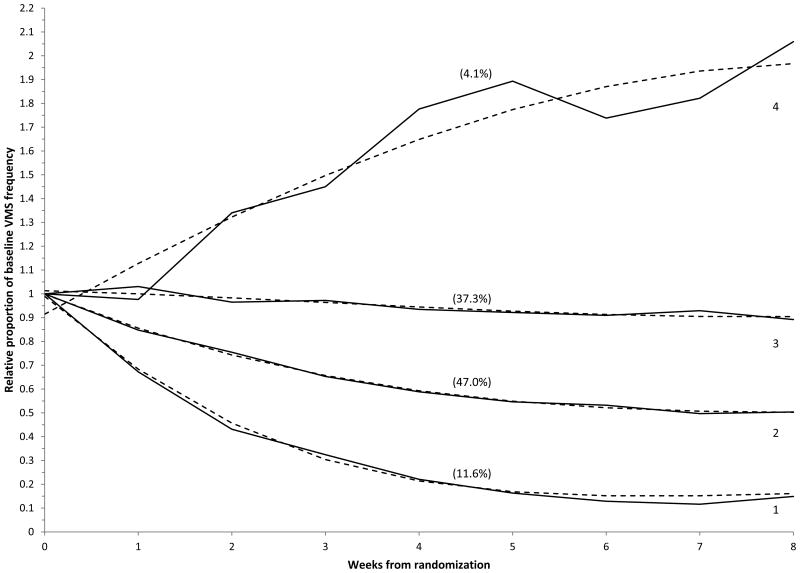

Analyses revealed four distinct trajectories of change in VMS frequency by week 8 in the acupuncture group. A small group of women (11.6%, n=19) had an 85% reduction in VMS. The largest group (47%, n=79) reported a 47% reduction in VMS frequency, 37.3% (n=65) of the sample showed only a 9.6% reduction in VMS frequency, and a very small group (4.1%, n=7) had a 100% increase in VMS. Among women in the waitlist control group, 79.5% reported a 10% decrease in VMS frequency at week 8. Baseline number of VMS, number of acupuncture treatments in the first 8 weeks, and traditional Chinese medicine diagnosis were significantly related to trajectory group membership in the acupuncture group.

Conclusions

Approximately half of the treated sample reported a decline in VMS frequency, but identifying clear predictors of clinical response to acupuncture treatment of menopausal VMS remains challenging.

Keywords: menopause, acupuncture, vasomotor symptoms, hot flashes

Introduction

Vasomotor symptoms (VMS), which include hot flashes and night sweats, are the most common and troubling symptoms associated with menopause.1,2 Although some women report experiencing the menopausal transition without any VMS,3 other women report that these symptoms can be frequent and severe and interfere with daily activities and quality of life.4-12 Recent estimates suggest that frequent menopausal VMS can continue for a median of 7.4 years.13 Further, VMS are the chief menopause-related problems for which women in the US seek medical attention.14-16

Estrogen therapy, alone or in combination with a progestogen, is currently the most effective treatment for VMS. Hormone therapy (HT), however, is associated with a number of risks, such as thromboembolic events and breast cancer, and some troublesome side effects, such as breast tenderness and irregular bleeding.17-21 Many women seek alternatives, including other pharmaceutical agents, herbal or dietary remedies, or behavioral therapies.22-25 Unfortunately, many of these agents also have side effects and/or have not been shown to be effective.23,26-29

A number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that acupuncture can effectively reduce the frequency and severity of VMS.30-36 A recent meta-analysis of 12 RCTs concluded that acupuncture improves the frequency and severity of VMS and menopause-related symptoms in women experiencing natural menopause, with clinical effects lasting up to 3 months.37 These studies, however, examined overall mean responses by study groups. As is the case with most medical and integrative treatments, practitioners recognize that acupuncture is not equally effective for all patients. However, little research has focused on identifying distinct patterns of response or the characteristics of patients that would predict response to acupuncture treatment.

Only one published study sought to identify patient characteristics related to response to acupuncture treatment for menopausal VMS. The ACUFLASH study compared traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) diagnosis patterns and acupuncture points between women who showed a 50% reduction in hot flashes and those who did not report a reduction in VMS and found no difference between groups in diagnoses or acupuncture points.34

We previously reported primary results from the Acupuncture in Menopause (AIM) study, a randomized clinical trial that evaluated the effectiveness of acupuncture for the treatment of menopause-related VMS.36 Results of that study showed that women who received up to 20 acupuncture treatments over 6 months had a 36.7% decrease in VMS frequency, as compared to an increase of 6.0% in a control group receiving usual care. Maximal reduction occurred by week 8, corresponding to a median of 8 acupuncture treatments.36 However, these results were based on overall mean responses within study groups and therefore obscure the heterogeneity of responses. The present study extends these trial results by using finite mixture modeling (SAS Proc TRAJ) to identify distinct groups of women in the intervention arm who exhibited different trajectories of change in VMS frequency following randomization to acupuncture treatment. We hypothesized that there would be varying patterns (trajectories) of relative VMS frequency, with some women exhibiting stronger patterns of decline compared to others. We also examined a set of participant predictors to determine their association with trajectory group membership. Identification of distinct trajectories could provide useful information to patients seeking relief from VMS and to the acupuncturists who treat them.

Methods

Study Design Overview

The present paper reports the results of secondary analyses of a pragmatic 2-site, 2-arm clinical trial of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women experiencing an average of ≥4 VMS per day who were randomized to either: 1) a 6-month course of up to 20 acupuncture treatments plus usual care; or 2) a waitlist control group consisting of usual care for 6 months followed by the same 6-month course of acupuncture treatments administered to study participants in the intervention, as previously described.36

Recruitment occurred between April 2011 and July 2013 at Wake Forest School of Medicine and Chapel Hill Doctors Healthcare Center in North Carolina. Follow-up continued through July 2014. The study was approved by the Wake Forest Health Sciences Institutional Review Board for both sites.

Study Participants

Eligible participants were perimenopausal or postmenopausal women aged 45-60 years experiencing ≥4 VMS/day. Perimenopause was defined as 3 or more months of self-defined amenorrhea; postmenopause was defined as amenorrhea for 12 or more months.38 Women who had undergone bilateral oophorectomy and/or hysterectomy prior to cessation of menses were classified as having surgical menopause. Exclusion criteria were: initiation of or change in dose of any treatment for VMS in the previous 4 weeks, initiation of or change in dose of an antidepressant in the previous 3 months, having received acupuncture for any indication in the previous 4 weeks or having received acupuncture from one of the study acupuncturists in the previous 6 months, self-reported health status as poor or fair during the telephone screening, or a diagnosis of hemophilia.

Procedures

Women were recruited through newspaper advertisements, radio announcements, and community postings. Initial eligibility was determined by a telephone screener. Eligible women were scheduled for a baseline study visit, at which time they were consented, completed a self-administered questionnaire, and received instructions on keeping a 2-week hot flash diary (described under Measures), which was then mailed back to study personnel and used to verify eligibility.

All women who returned a completed 2-week diary to study personnel and met the criterion of an average of ≥4 VMS per day were scheduled for their first acupuncture treatment visit to occur within 3 weeks of eligibility confirmation. At that visit, the acupuncturist provided a TCM diagnosis so that all women had a baseline diagnosis. Following diagnosis, acupuncturists logged into the study website and completed the randomization process to identify group assignment. Women randomized to the acupuncture group received their first treatment at that time.

All study participants returned for study visits at 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12 months post-randomization to complete study questionnaires. Study staff who administered questionnaires were blinded to group assignment. Study participants were paid $35 for their baseline visit and $25 for completion of each of the follow-up visits. Those who completed all 6 visits were paid an additional $50.

Randomization

Eligible women were randomized to one of the two groups using a 4:1 distribution (with 80% of women randomized to the acupuncture group). This distribution optimized statistical power for identifying possible subgroups with different clinical characteristics that predict different overall effects up to 6 months after completion of the 6-month treatment period for participants randomized to the intervention group.

Acupuncture Treatment

Participants assigned to the acupuncture group were allowed to have up to 20 acupuncture treatments by one of four study acupuncturists over a 6-month period. The frequency of treatments was determined by the acupuncturist and study participant. All study acupuncturists were licensed and had 8 to 33 years of practice experience prior to the start of this clinical trial. Acupuncturists ascribed a primary TCM diagnosis and up to two secondary TCM pattern diagnoses to each study participant. Study acupuncturists obtained a symptom history from participants and conducted a physical examination that included pulse palpation and tongue inspection. Information from the symptom history and physical examination informed participants' diagnoses, which in turn informed acupuncture point selection and individualized treatment plans. TCM diagnoses were reassessed (and changed, if indicated) at each subsequent treatment session. Study acupuncturists were permitted to change acupuncture point selection and other aspects of treatment if clinically indicated at each treatment session.

Sterile, disposable acupuncture needles were inserted through the skin to a depth of from 0.5 to 3 cm based on anatomical location. No restrictions were placed on the duration of each treatment or on the application of other treatment modalities, such as manual or electrical stimulation of acupuncture needles at selected acupuncture point locations, but prescribing Chinese herbal remedies was not permitted.

Measures

The primary study outcome was the percent change in the frequency of hot flashes and night sweats as measured by the Daily Diary of Hot Flashes (DDHF) from the baseline daily VMS value. The DDHF records the frequency and severity (using a 4- point scale from mild to very severe) of each VMS and allows the investigator to calculate VMS frequency and a VMS index score (the sum of the number of VMS multiplied by each level of severity).39 Because our previous analyses showed identical results for both VMS frequency and the index score,36 we focus only on VMS frequency in the present analyses. Women were asked to record the number of VMS they experienced each day during the treatment phase of the trial and were provided tally counters to help them keep track of the number of hot flashes they experienced throughout the day. Baseline VMS frequency was calculated by averaging the number of VMS recorded in the diaries for the last 14 days available prior to randomization. After randomization, we averaged the daily VMS frequency each week to provide a daily average measure for each week. For the figures, we quantified the weekly VMS frequency as a relative fraction of the baseline frequency, standardizing the baseline frequency to 1.0 (or 100%). For example, a woman who reported an average of 10 VMS per day during the 2-week period prior to randomization and an average of 8 VMS per day during the 8th week after randomization would have a relative proportion of 0.8 for VMS frequency at week 8; equivalently, she experienced a 20% reduction in VMS frequency at the Week 8 timepoint.

We collected daily VMS diary data from all participants during the first 6 months of the trial. However, from a clinical decision-making perspective for women seeking a therapeutic modality to obtain relief from VMS, a 6-month time period is relatively long. We therefore focused the present analysis on the first 8 weeks only, which we believe is a reasonable time period for assessing a woman's initial response to acupuncture treatment. Although our primary interest was to identify different patterns of responses to treatment during the first 8 weeks post-randomization, we also modeled the control group to provide benchmark information on women who did not receive acupuncture.

Predictors

The following variables (all collected at baseline) were examined as potential factors related to VMS trajectory. Sociodemographic characteristics included age, race (non-Hispanic white/African-American/other), education (less than college degree/college degree/greater than college degree), and marital/partner status (married or living in a marriage-like relationship/never married, divorced, separated, or widowed). Psychosocial factors included depressive symptoms assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale, short form (CESD-10)40; anxiety symptoms measured with the General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7)41; perceived stress assessed by the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)42; and symptom sensitivity measured by the 10-item Somatosensory Amplification Scale (SSAS), which is a measure of sensitivity to a range of uncomfortable bodily sensations and physiologic states that are typically symptomatic of disease.43

Also included were the number of hot flashes at baseline, degree of hot flash interference as measured by the Hot Flash Related Daily Interference Scale (HFRDIS),44 menopause status (perimenopausal/postmenopausal/surgical), current use of HT (yes/no), previous use of acupuncture (yes/no), expectations about how helpful acupuncture would be in reducing the number of hot flashes with an 11-point response scale from 0 (not at all helpful) to 10 (extremely helpful), and site (Wake Forest/Chapel Hill Doctors). Primary TCM diagnosis was grouped by kidney yin deficiency, kidney yin and yang deficiency, and other. The “other” category included diagnoses that were too infrequently used to analyze separately: kidney and heart not harmonized (n=11), kidney/liver yin deficiency with liver yang rising (n=10), liver Qi stagnation with stagnant heat (n=4), spleen Qi and heart blood deficiency (n=5), lung and kidney yin deficiency (n=1), and lu/ki yin xu (n=1).

Statistical Analysis

The group-based SAS finite mixture model procedure PROC TRAJ was applied to identify distinct subgroups of women who followed similar trajectories over time in their weekly relative proportion of VMS (all measured against the baseline frequency). PROC TRAJ identifies distinctive time-based progressions and can model variables with a censored normal distribution.45 The censored normal distribution accurately describes the distribution of relative VMS frequencies in our sample, where there is a clustering of scores toward the lower end and where no values can be below 0. The TRAJ procedure assumes that missing data are missing completely at random.45

We modeled separate trajectories for both the acupuncture and control groups. Relative frequencies of VMS were modeled as functions of the first 8 weeks since randomization and to include an intercept and linear, quadratic, and cubic terms for weeks since randomization. Models were tested that contained from two to seven trajectory groups. Although the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was used as an initial guide in determining the optimal number of trajectory groups (a higher BIC indicates a better model fit), we followed the recommendation of Nagin and used a combination of a statistical criterion (the BIC) and judgment (new information gained through the addition of a distinctively different trajectory; trajectory group sizes) to select the optimal number of trajectory groups.45

The TRAJ procedure assigns posterior probabilities of group membership to all individuals in the analysis. These probabilities measure a specific individual's likelihood of belonging to each of the model's trajectory groups. Individuals were assigned to the trajectory group for which they had the maximum posterior probability. For all graphic displays, both the observed mean percent change VMS frequency scores over time are shown for the women assigned to the particular trajectory group as well as the predicted, or expected, trajectory plot line based on the linear, quadratic, and cubic terms in the model.

A second objective of our study was to identify factors predicting VMS trajectory for women who received acupuncture. (We did not identify predictors of trajectory membership among the control group who did not receive treatment, both because of the relatively small sample size in this group, and because it was not one of our study aims.) After women in the acupuncture group were assigned to trajectory groups, associations between group membership and the previously described predictors were assessed using the Freeman-Halton test (an extension of the Fisher's exact text for tables larger than 2x2) for categorical variables and F-tests for continuous variables.

All analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Of the 329 women considered eligible by the screener, 272 completed an initial baseline study visit. Of these, 28 women were subsequently determined to be ineligible based on having too few VMS recorded in their 2-week hot flash diaries, and 35 declined further participation. Thus, 209 women were enrolled in the study and randomized. Study retention was excellent, with 92% remaining in the study at 8 weeks.

Sample Characteristics

Sample characteristics by group assignment are shown in Table 1. There were no significant group differences in baseline characteristics. Participants had a mean number of 9.5 (SD=5.0; median=8.5) VMS/day at baseline. The majority of the sample (76%) was white; 22% of participants were African-American. The majority of participants (57%) were naturally postmenopausal, and 27% had undergone surgical menopause. Two participants in the acupuncture group and no control participants were using HT at randomization.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study sample.

| Characteristic | Total Sample N=209 |

Acupuncture N=170 |

Control N=39 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at randomization, mean (SD),y | 53.8 (3.5) | 53.8 (3.5) | 53.6 (3.6) | 0.65 |

| No. VMS/day at baseline,a mean (SD) | 9.5 (5.0) | 9.4 (5.1) | 9.8 (5.0) | 0.68 |

| Race, No. (%) | 0.27 | |||

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 46 (22.0) | 38 (22.4) | 8 (20.5) | |

| Hispanic, American Indian or Alaskan Native | 4 (1.9) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (5.1) | |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 159 (76.1) | 130 (76.5) | 29 (74.4) | |

| Marital Status, No. (%) | 0.74 | |||

| Married or living in a marriage-like relationship | 162 (77.5) | 131 (77.1) | 31 (79.5) | |

| Never married, divorced, separated or widowed | 47 (22.5) | 39 (22.9) | 8 (20.5) | |

| Education, No. (%) | 0.39 | |||

| Less than college | 92 (44.0) | 75 (44.1) | 17 (43.6) | |

| College degree | 47 (22.5) | 41 (24.1) | 6 (15.4) | |

| Beyond college degree | 70 (33.5) | 54 (31.8) | 16 (41.0) | |

| Menopausal status, No. (%) | 0.94 | |||

| Perimenopause | 35 (16.7) | 29 (17.1) | 6 (15.4) | |

| Postmenopause | 118 (56.5) | 95 (55.9) | 23 (59.0) | |

| Surgical menopause | 56 (26.8) | 46 (27.1) | 10 (25.6) | |

| On Hormone Therapy (HT) at randomization | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.2) | 0 | 0.99b |

| Prior use of acupuncture, No. (%) | 50 (23.9) | 41 (24.1) | 9 (23.1) | 0.89 |

VMS, vasomotor symptoms.

Baseline refers to the 2 weeks of hot flash diaries completed just prior to randomization.

p-value from Freeman-Halton test.

Trajectory Analyses

We determined that the optimal number of trajectories for the intervention group (n=170), based on considering both the BIC and the minimum group size, was four; the smallest group in this four-group solution contained 4% of the sample (n=7). Solutions that allowed more than four trajectory groups, while having better BIC scores (Table 2), contained groups that were less than 1% (fewer than n=2) of the sample. The posterior probabilities generated by the 4-group trajectory model and used to assign individuals to one of the four trajectory groups were higher than 0.85 for 90% of the participants, and were above 0.5 for all. As seen in Figure 1, there was a small group of women (11.6%, n=19) who had a very strong response to acupuncture, with an 85.5% reduction in mean VMS frequency by week 8. The largest trajectory group, Group 2 (n=79), consisted of 47% of the women who had a 46.8% reduction in mean VMS frequency. Group 3 (N= 65) was the next largest group, consisting of 37.3% of the sample who showed a small decrease (9.6%) in mean VMS frequency. Finally, a small group of women (4.1%; n=7) had a 100% increase over baseline in mean VMS frequency.

Table 2. Model selection results for acupuncture group.

| Estimated probability (estimated % in each group) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| No of Groups | BIC | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 100.0 | |||||||

| 2 | -374.41 | 60.2 | 39.8 | |||||

| 3 | -200.39 | 51.2 | 44.2 | 4.6 | ||||

| 4 | -124.30 | 11.6 | 47.0 | 37.3 | 4.1 | |||

| 5 | -116.50 | 0.6 | 11.7 | 46.3 | 37.3 | 4.1 | ||

| 6 | -61.38 | 0.6 | 11.6 | 44.3 | 36.7 | 5.1 | 1.8 | |

| 7 | -59.16 | 0.6 | 11.3 | 31.8 | 14.3 | 35.2 | 5.1 | 1.8 |

BIC, Bayesian information criterion.

Figure 1.

Predicted (dashed lines) and observed (solid lines) mean levels of relative VMS frequency (relative to baseline) in four trajectory groups. Percentages refer to proportion of women in acupuncture arm who were categorized into trajectory group.

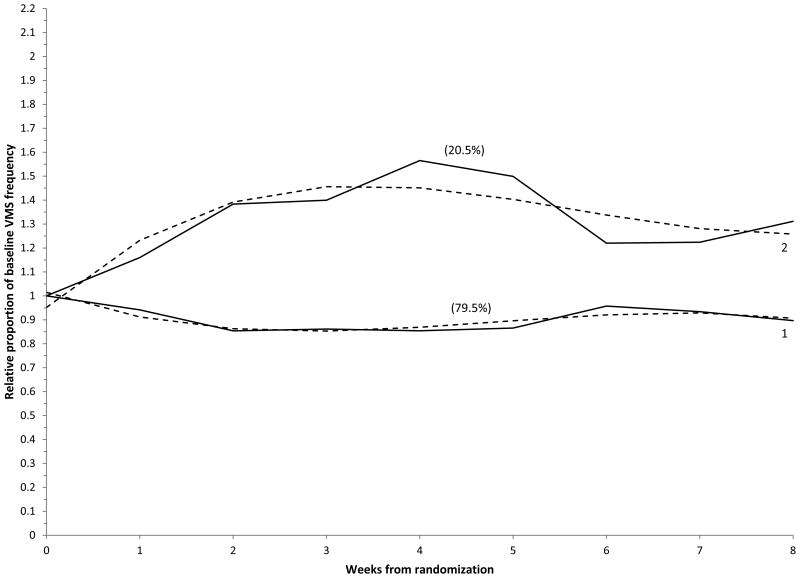

Figure 2 shows the trajectory groups for women in the control group. Due in part to the small size of this subsample, the 2-group solution was the best model and showed that 79.5% of women in this group had a reduction in mean VMS frequency of 10% at week 8. A small group of women (20.5%, n=8) reported a100% increase in VMS over the 8 weeks.

Figure 2.

Predicted (dashed lines) and observed (solid lines) mean levels of relative VMS frequency (relative to baseline) in two trajectory groups. Percentages refer to proportion of women in the control arm who were categorized into trajectory group.

Factors Related to Trajectory Group Membership

Table 3 presents the means for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables of women in each trajectory for the acupuncture group. The number of acupuncture treatments in the first 8 weeks of the study was the most significant predictor of group membership (p<.001). The small group of women whose VMS increased (group 4) had undergone significantly fewer acupuncture treatments (mean 5.3) over the first 8 weeks compared to women in the other groups who did not differ among themselves (means of 8.3, 8.6, and 9.1). This small group also had significantly fewer VMS at baseline than did the three other groups combined (5.1 vs. 9.6; p-value for contrast 0.027-not shown in table.) (Note that the global significance test among the 4 separate groups for differences in VMS frequency at baseline was not significant due to the similarity among groups 1, 2, and 3 for this measure). The primary TCM diagnosis was significantly different across groups (p=.038). Women in trajectory group 1, who had the greatest reduction in VMS frequency, were less likely to receive a diagnosis of kidney yin deficiency (26.3% received this diagnosis compared to 43.0%, 56.9%, and 42.9%, respectively, in groups 2, 3, and 4) and were more likely to receive one of the lesser used diagnoses (42.1% received a diagnosis in the Other category, compared to 21.5%, 10.8%, and 0.0%, respectively, for groups 2, 3, and 4). Because TCM diagnosis varied by acupuncturist, we also examined whether acupuncturist was related to trajectory group, but this relationship was not significant (p=0.295).

Table 3. Baseline characteristics related to trajectory group membership.

| Characteristic | Trajectory Group | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| N=19 | N=79 | N=65 | N=7 | ||

| Age at randomization, mean (SD), y | 52.5 (0.8) | 53.5 (0.4) | 54.6 (0.4) | 53.7 (1.3) | 0.07 |

| No. VMS/day at baselinea, mean (SD) | 9.1 (1.2) | 9.6 (0.6) | 9.6 (0.6) | 5.1 (1.9) | 0.14 |

| No. acupuncture treatments (weeks 1-8), mean (SD) | 8.3 (0.6) | 8.6 (0.3) | 9.1 (0.3) | 5.3 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| No. acupuncture treatments (weeks 9-26), mean (SD) | 7.8 (0.9) | 7.3 (0.5) | 7.6 (0.5) | 5.4 (1.6) | 0.56 |

| Race, No. (%) | 0.74 | ||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 15 (78.9) | 59 (74.7) | 52 (80.0) | 4 (57.1) | |

| Non-White | 4 (21.1) | 20 (25.3) | 13 (20.0) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Education, No. (%) | 0.15 | ||||

| Less than college | 11 (57.9) | 35 (44.3) | 27 (41.5) | 2 (28.6) | |

| College degree | 2 (10.5) | 18 (22.8) | 21 (32.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Beyond college degree | 6 (31.6) | 26 (32.9) | 17 (26.2) | 5 (71.4) | |

| Marital status, No. (%) | 0.84 | ||||

| Never married, divorced, separated, widowed | 4 (21.1) | 20 (25.3) | 13 (20.0) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Married/in a marriage-like relationship | 15 (78.9) | 59 (74.7) | 52 (80.0) | 5 (71.4) | |

| Traditional Chinese medicine primary diagnosis, No. (%) | 0.038 | ||||

| Kidney yin and yang deficiency | 6 (31.6) | 28 (35.4) | 21 (32.3) | 4 (57.1) | |

| Kidney yin deficiency | 5 (26.3) | 34 (43.0) | 37 (56.9) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Other | 8 (42.1) | 17 (21.5) | 7 (10.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Site, No. (%) | 0.42 | ||||

| Chapel Hill Doctors | 5 (26.3) | 35 (44.3) | 26 (40.0) | 4 (57.1) | |

| Wake Forest | 14 (73.7) | 44 (55.7) | 39 (60.0) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Menopause Status, No. (%) | 0.46 | ||||

| Perimenopause | 4 (21.1) | 12 (15.2) | 10 (15.4) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Postmenopause | 9 (47.4) | 49 (62.0) | 37 (56.9) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Surgical menopause | 6 (31.6) | 18 (22.8) | 18 (27.7) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Doing anything else for hot flashes (screening), No. (%) | 0.80 | ||||

| No | 19 (100.0) | 75 (94.9) | 60 (92.3) | 7 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.1%) | 5 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Prior use of acupuncture, No. (%) | 0.50 | ||||

| No | 16 (84.2) | 56 (70.9) | 52 (80.0) | 5 (71.4) | |

| Yes | 3 (15.8) | 23 (29.1) | 13 (20.0) | 2 (28.6) | |

| HFRDIS score, mean (SD) | 46.0 (5.6) | 45.5 (2.7) | 41.7 (3.0) | 55.0 (9.9) | 0.53 |

| CESD score, mean (SD) | 6.3 (1.2) | 8.8 (0.6) | 7.4 (0.7) | 10.0 (2.0) | 0.15 |

| GAD7 score, mean (SD) | 3.8 (1.2) | 6.0 (0.6) | 4.8 (0.7) | 8.3 (2.0) | 0.13 |

| Perceived Stress Scale score, mean (SD) | 3.7 (0.8) | 4.5 (0.4) | 4.2 (0.4) | 4.3 (1.3) | 0.81 |

| Symptom sensitivity (SSAS) score, mean (SD) | 2.6 (0.1) | 2.8 (0.1) | 2.8 (0.1) | 3.0 (0.2) | 0.53 |

| Expectations - influence number of VMS, mean (SD) | 8.4 (0.4) | 7.9 (0.2) | 7.6 (0.2) | 9.0 (0.7) | 0.16 |

| % VMS/day change at 26 weeks, mean (SD) | -73.5 (11.3) | -41.6 (5.4) | -23.3 (5.8) | 32.4 (19.5) | <0.001 |

| Pairwise group comparisonsb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 vs 2 | 1 vs 3 | 1 vs 4 | 2 vs 3 | 2 vs 4 | 3 vs 4 | 1,2,3 vs 4 | |

| Age at randomization | 0.25 | 0.017 | 0.44 | 0.049 | 0.91 | 0.47 | |

| No. acupuncture treatments (0-8 weeks) | 0.63 | 0.21 | 0.006 | 0.22 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| No. VMS/day at baselinea | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.07 | 0.99 | 0.022 | 0.023 | 0.027 |

| % VMS/day change at 8 weeks | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

CESD, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale, short form; GAD7, General Anxiety Disorder-7; HFRDIS, Hot Flash Related Daily Interference Scale; SSAS, Somatosensory Amplification Scale; SD, standard deviation; VMS, vasomotor symptoms.

Baseline refers to the 2 weeks of hot flash diaries completed just prior to randomization.

P-values obtained from a linear model and comparing the least-squares means of different groups.

There were no significant differences in site, race, marital status, education, menopause status, previous use of acupuncture, or use of other treatments for hot flashes across the four trajectory groups. Women in group 1 (who showed the largest decrease in VMS frequency over the 8 weeks) were slightly younger and reported fewer depressive symptoms and less anxiety and perceived stress at baseline than did women in the other groups, though these differences did not reach statistical significance.

As previously mentioned, trajectory group identification was based on the first 8 weeks of treatment. To determine how women in these groups responded over a longer period of time, we examined the percent change in VMS frequency for each group at 26 weeks, which was the end of treatment. The difference in VMS reduction by group at 26 weeks was highly significant (p<.001). Groups 1 and 2 (the two trajectory groups that had the largest decrease in VMS at 8 weeks) maintained their reduction in VMS. Group 3, which demonstrated a 9.6% reduction in average VMS frequency at 8 weeks, reported a 23.3% reduction (from baseline) in average VMS frequency at 26 weeks.

Discussion

Previous studies of acupuncture treatment for VMS have typically reported a 30-60% reduction in VMS frequency among women receiving treatment.30-36 These studies, however, do not provide data on the heterogeneity of responses to acupuncture. The present study showed that 59% of women had at least a 40% reduction in the frequency of VMS over 8 weeks (corresponding to approximately 8 treatments in our study). A small group of women (11% of the total sample) achieved a very large response to acupuncture (80% reduction in VMS frequency) after just a few weeks of treatment. We also found that 41% of women receiving acupuncture had essentially no reduction in VMS frequency at 8 weeks, but that among this group of initial non-responders to acupuncture treatments, VMS frequency decreased, on average, by 23% after 6 months of acupuncture treatments. These data highlight different patterns of response to acupuncture.

Identification of patient characteristics that predict response to acupuncture has the potential to inform clinical practice. However, after studying a variety of sociodemographic characteristics, psychological factors, and expectations prior to treatment, we found few factors obtained at the initial presentation to acupuncturists that predicted how women would respond. Our findings do not provide compelling evidence of a robust dose-response relationship. We observed no significant difference in the number of acupuncture treatments administered during the 8-week study period among the three trajectory groups that demonstrated a clinical response to acupuncture.

We did find a significant effect of TCM diagnosis; women who had a very strong response to acupuncture (group 1) were less likely to have been diagnosed with kidney yin deficiency. Kidney yin deficiency usually develops over a long period of time, whereas many of the other TCM diagnoses in this cohort of women, such as kidney and heart not harmonized, spleen qi and heart blood deficiency, or liver qi stagnation with stagnant heat, are generally considered to be relatively acute conditions. It is possible that women diagnosed with the latter conditions respond more quickly to acupuncture treatment than do those presenting with more chronic conditions, as manifested by yin deficiency syndromes. This finding may have implications for predicting responses to acupuncture for VMS and warrants further study. In contrast to our study, the ACUFLASH study34 did not find a significant difference in primary TCM diagnosis between responders and non-responders, despite the fact that both studies permitted the acupuncturists to formulate individualized acupuncture treatment plans based on patients' TCM pattern diagnoses. This may be due, in part, to differing distributions of TCM diagnoses among postmenopausal women in Norway and the United States, and/or to different approaches to defining response to treatment.

We did not find that expectations about acupuncture at baseline were related to response. However, this may be because we did not use the validated Acupuncture Expectancy Scale,46 which allows for a wider distribution (4-20) of scores than did our expectations rating scale. Study participants in all groups expected acupuncture to be helpful. There was little difference in the baseline number of VMS among the groups, though women in the small group that had an increase in VMS had fewer VMS at baseline. There was some indication that women in the high-response group had the lowest levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, symptom sensitivity, and perceived stress, but these variables were not significant and did not follow a linear pattern.

Strengths of this research include: a pragmatic, randomized clinical trial design with a study protocol designed to simulate contemporary clinical practice; a meaningful patient-reported outcome (hot flash frequency recorded continuously over the 8-week study period); a high retention rate; and a nearly complete set of follow-up data. Limitations include small sample sizes in two of the trajectory groups, which may have precluded finding significant differences in covariates among the groups. Although women were not randomized to study acupuncturist, as noted previously we found no relationship between study acupuncturist and trajectory group membership.

The present analysis provides new information on heterogeneity of response to acupuncture. We did not identify a clear predictor of clinical response to acupuncture, but our findings suggested that women with a primary TCM diagnosis other than kidney yin deficiency demonstrated a robust clinical response to acupuncture within the first 8 weeks of treatment. Most women with kidney yin deficiency, however, experienced a significant reduction in VMS frequency over a longer period of time while undergoing acupuncture treatment. This finding may help acupuncturists identify a subset of women who may be particularly responsive to acupuncture during the first 8 weeks of treatment.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the majority of women may experience a significant reduction in menopause-related VMS frequency after 8 weeks of acupuncture treatment, and that there is a subgroup of women who are likely to experience an especially rapid and strong clinical response to acupuncture. We did not identify clear predictors of clinical response to acupuncture treatment, and our data do not lend support to the hypothesis that there is a robust relationship between the number of acupuncture treatments received and the reduction in VMS frequency after 8 weeks of treatment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank the study acupuncturists: Boyd Bailey, MAc, LAc; Wunian Chen, MD, LAc; Keoni Teta, ND, LAc, and Helen Wang, PhD, LAc.

Funding Support: This study was supported by grant R01AT005854 from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIM).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest/financial disclosure: Dr. Coeytaux has a financial interest in two organizations involved in recruiting study subjects and administering acupuncture treatments at one of the two study sites. My spouse is the primary shareholder of IHEAL, Inc, which is an organization that was subcontracted by Wake Forest University as a site for subject recruitment and treatment. A conflict of interest management plan was developed by Duke University and is available upon request.

References

- 1.Kronenberg F. Hot flashes: Epidemiology and physiology. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1990;592:52–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb30316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avis NE, Brockwell S, Colvin A. A universal menopausal syndrome? Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 12B):37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avis NE, Crawford SL, McKinlay SM. Psychosocial, behavioral, and health factors related to menopause symptomatology. Womens Health. 1997;3:103–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daly E, Gray A, Barlow D, McPherson K, Roche M, Vessey M. Measuring the impact of menopausal symptoms on quality of life. Brit Med J. 1993;307:836–840. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6908.836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avis NE, Ory M, Matthews KA, Schocken M, Bromberger J, Colvin A. Health-related quality of life in a multiethnic sample of middle-aged women: Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Med Care. 2003;41:1262–1276. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093479.39115.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpenter JS, Johnson D, Wagner L, Andrykowski M. Hot flashes and related outcomes in breast cancer survivors and matched comparison women. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:E16–E25. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.E16-E25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ledesert B, Ringa V, Breart G. Menopause and perceived health status among the women of the French GAZEL cohort. Maturitas. 1994;20:113–120. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumari M, Stafford M, Marmot M. The menopausal transition was associated in a prospective study with decreased health functioning in women who report menopausal symptoms. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:719–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuh JL, Wang SJ, Lee SJ, Lu SR, Juang KD. Quality of life and menopausal transition for middle-aged women on Kinmen island. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:53–61. doi: 10.1023/a:1022074602928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hays J, Ockene JK, Brunner RL, et al. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on health-related quality of life. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1839–1854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumel JE, Chedraui P, Baron G, et al. A large multinational study of vasomotor symptom prevalence, duration, and impact on quality of life in middle-aged women. Menopause. 2011;18:778–785. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318207851d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams RE, Levine KB, Kalilani L, Lewis J, Clark RV. Menopause-specific questionnaire assessment in US population-based study shows negative impact on health-related quality of life. Maturitas. 2009;62:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:531–539. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johannes CB, Crawford SL, Posner JG, McKinlay SM. Longitudinal patterns and correlates of hormone replacement therapy use in middle-aged women. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:439–452. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams RE, Kalilani L, DiBenedetti DB, Zhou X, Fehnel SE, Clark RV. Healthcare seeking and treatment for menopausal symptoms in the United States. Maturitas. 2007;58:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholson WK, Ellison SA, Grason H, Powe NR. Patterns of ambulatory care use for gynecologic conditions: a national study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:523–530. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.111795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnabei VM, Grady D, Stovall DW, et al. Menopausal symptoms in older women and the effects of treatment with hormone therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:1209–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grady D, Herrington D, Bittner V, et al. Cardiovascular disease outcomes during 6.8 years of hormone therapy: Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study follow-up (HERS II) JAMA. 2002;288:49–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manson JE, Hsia J, Johnson KC, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. New Engl J Med. 2003;349:523–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wassertheil-Smoller S, Hendrix S, Limacher M, et al. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on stroke in postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2673–2684. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newton KM, Buist DS, Keenan NL, Anderson LA, LaCroix AZ. Use of alternative therapies for menopause symptoms: results of a population-based survey. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:18–25. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nedrow A, Miller J, Walker M, Nygren P, Huffman LH, Nelson HD. Complementary and alternative therapies for the management of menopause-related symptoms: a systematic evidence review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1453–1465. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.14.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessel B, Kronenberg F. The role of complementary and alternative medicine in management of menopausal symptoms. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2004;33:717–739. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beal MW. Women's use of complementary and alternative therapies in reproductive health care. J Nurse Midwifery. 1998;43:224–234. doi: 10.1016/s0091-2182(98)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kronenberg F, Fugh-Berman A. Complementary and alternative medicine for menopausal symptoms: A review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:805–813. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-10-200211190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loprinzi CL, Kubler JW, Sloan JA, et al. Venlafaxine in management of hot flashes in survivors of breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356:2059–2063. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huntley AL, Ernst E. A systematic review of herbal medicinal products for the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2003;10:465–476. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000058147.24036.B0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagamani M, Kelver ME, Smith ER. Treatment of menopausal hot flashes with transdermal administration of clonidine. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:561–565. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(87)90050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vincent A, Barton DL, Mandrekar JN, et al. Acupuncture for hot flashes: a randomized, sham-controlled clinical study. Menopause. 2007;14:45–52. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000227854.27603.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim KH, Kang KW, Kim DI, et al. Effects of acupuncture on hot flashes in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women-a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Menopause. 2010;17:269–280. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181bfac3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Painovich JM, Shufelt CL, Azziz R, et al. A pilot randomized, single blind, placebo-controlled trial of traditional acupuncture for vasomotor symptoms and mechanistic pathways of menopause. Menopause. 2012;19:54–61. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31821f9171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nedeljkovic M, Tian L, Ji P, et al. Effects of acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine (Zhi Mu 14) on hot flushes and quality of life in postmenopausal women: results of a four-arm randomized controlled pilot trial. Menopause. 2014;21:15–24. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31829374e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borud EK, Alraek T, White A, et al. The acupuncture on hot flushes among menopausal women (ACUFLASH) study, a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2009;16:484–493. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818c02ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avis NE, Legault C, Coeytaux RR, et al. A randomized, controlled pilot study of acupuncture treatment for menopausal hot flashes. Menopause. 2008;15:1070–1078. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31816d5b03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Avis NE, Coeytaux R, Isom S, Prevette K, Morgan T. Acupuncture in menopase (AIM): a pragmatic, randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2016 doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000597. Epub March 18, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiu HY, Pan CH, Shyu YK, Han BC, Tsai PS. Effects of acupuncture on menopause-related symptoms and quality of life in women on natural menopause: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2015;22:234–244. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, et al. Executive summary: Stages of reproductive aging workshop (STRAW) Fertil Steril. 2001;76:874–878. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02909-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sloan JA, Loprinzi CL, Novotny PJ, Barton DL, Lavasseur BI, Windschitl H. Methodologic lessons learned from hot flash studies. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4280–4290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.23.4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barsky AJ, Wyshak G, Klerman GL. The somatosensory amplification scale and its relationship to hypochondriasis. J Psychiatr Res. 1990;24:323–334. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(90)90004-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carpenter JS. The Hot Flash Related Daily Interference Scale: a tool for assessing the impact of hot flashes on quality of life following breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:979–989. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagin DS. Group-Based Modeling of Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mao JJ, Xie SX, Bowman MA. Uncovering the expectancy effect: the validation of the acupuncture expectancy scale. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16:22–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]