Abstract

Introduction

For open and endoscopic inguinal hernia surgery, it has been demonstrated that low-volume surgeons with fewer than 25 and 30 procedures, respectively, per year are associated with significantly more recurrences than high-volume surgeons with 25 and 30 or more procedures, respectively, per year. This paper now explores the relationship between the caseload and the outcome based on the data from the Herniamed Registry.

Patients and methods

The prospective data of patients in the Herniamed Registry were analyzed using the inclusion criteria minimum age of 16 years, male patient, primary unilateral inguinal hernia, TEP or TAPP techniques and availability of data on 1-year follow-up. In total, 16,290 patients were enrolled between September 1, 2009, and February 1, 2014. Of the participating surgeons, 466 (87.6 %) had carried out fewer than 25 endoscopic/laparoscopic operations (low-volume surgeons) and 66 (12.4 %) surgeons 25 or more operations (high-volume surgeons) per year.

Results

Univariable (1.03 vs. 0.73 %; p = 0.047) and multivariable analysis [OR 1.494 (1.065–2.115); p = 0.023] revealed that low-volume surgeons had a significantly higher recurrence rate compared with the high-volume surgeons, although that difference was small. Multivariable analysis also showed that pain on exertion was negatively affected by a lower caseload <25 [OR 1.191 (1.062–1.337); p = 0.003]. While here, too, the difference was small, the fact that in that group there was a greater proportion of patients with small hernia defect sizes may have also played a role since the risk in that group was higher. In this analysis, no evidence was found that pain at rest [OR 1.052 (0.903–1.226); p = 0.516] or chronic pain requiring treatment [OR 1.108 (0.903–1.361); p = 0.326] were influenced by the surgeon volume.

Summary

As confirmed by previously published studies, the data in the Herniamed Registry also demonstrated that the endoscopic/laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery caseload impacted the outcome. However, given the overall high-quality level the differences between a “low-volume” surgeon and a “high-volume” surgeon were small. That was due to the use of a standardized technique, structured training as well as continuous supervision of trainees and surgeons with low annual caseload.

Keywords: Inguinal hernia, TEP, TAPP, Surgeon volume, Outcome

In the Guidelines of the European Hernia Society (EHS), the open Lichtenstein and Plug techniques as well as the endoscopic techniques (TEP, TAPP) are recommended as the best evidence-based options for the repair of a primary unilateral inguinal hernia, providing the surgeon is sufficiently experienced in the specific procedure [1, 2]. The Consensus Development Conference of the European Association of Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) and the Guidelines of the International Endohernia Society (IEHS) formulated as a statement that endoscopic groin hernia repair was considered to be more complex than open groin hernia repair [3–5]. Therefore, the learning curve for performing endoscopic inguinal hernia repair is longer than for open Lichtenstein repair and ranges between 50 and 100 procedures, with the first 30–50 being the most critical [1]. The Danish Hernia Database demonstrated on the basis of 14,532 endoscopic/laparoscopic inguinal hernia operations that, in institutions with fewer than 50 endoscopic/laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs per year, the recurrence rate at 9.97 versus 6.06 % was significantly higher compared with in institutions with more than 50 endoscopic/laparoscopic inguinal hernia operations per year (p < 0.0001) [6].

In the Swedish Hernia Registry, there was a significantly higher rate of recurrences for surgeons who carried out one-to-five repairs a year compared with surgeons who performed more repairs [7].

Data on open inguinal hernia surgery in the Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System Database on 151,322 patients with primary inguinal hernia repairs revealed that low-volume surgeons with fewer than 25 procedures per year had significantly more recurrences than high-volume surgeons with 25 or more procedures per year (hazard ratio 1.23; 95 % confidence interval 1.11–1.36; p < 0.001) [8]. Likewise, a retrospective analysis from the Mayo Clinic of 1601 patients with 2410 inguinal hernia repairs in the TEP technique demonstrated that higher annual surgeon volume (>30 vs. 15–30 vs. <15 repairs per year) was associated with improved outcomes as shown by the respective rates for intra- (1 vs. 2.6 vs. 5.6 %) and postoperative (13 vs. 27 vs. 36 %) complications and hernia recurrence (1 vs. 4 vs. 4.3 %) (all p < 0.05) [9]. Based on data from the Herniamed Registry [10], this paper now explores whether in a hernia registry too, with several surgeons participating in endoscopic/laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery, a difference was also identified between those surgeons with fewer than 25 procedures per year compared with surgeons with 25 and more procedures.

Materials and methods

The Herniamed quality assurance study is a multicenter, internet-based hernia registry [10] into which 460 participating hospitals and surgeons engaged in private practice (Herniamed Study Group) in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland (Status: March 19, 2015) had entered data prospectively on their patients who had undergone hernia surgery. All postoperative complications occurring up to 30 days after surgery are recorded. On one-year follow-up, postoperative complications are once again reviewed when the general practitioner and patients complete a questionnaire. On one-year follow-up, the general practitioner and patients are also asked about any recurrences, pain at rest, pain on exertion, and chronic pain requiring treatment.

In the present analysis, prospective data on male primary unilateral inguinal hernias, operated on in either the total extraperitoneal patch plasty (TEP) or transabdominal patch plasty (TAPP) technique, were analyzed to identify whether surgery had been performed by a surgeon with fewer than 25 or with 25 or more endoscopic/laparoscopic inguinal hernia operations per year. The registry does not, of course, provide any information on the actual experience of individual surgeons.

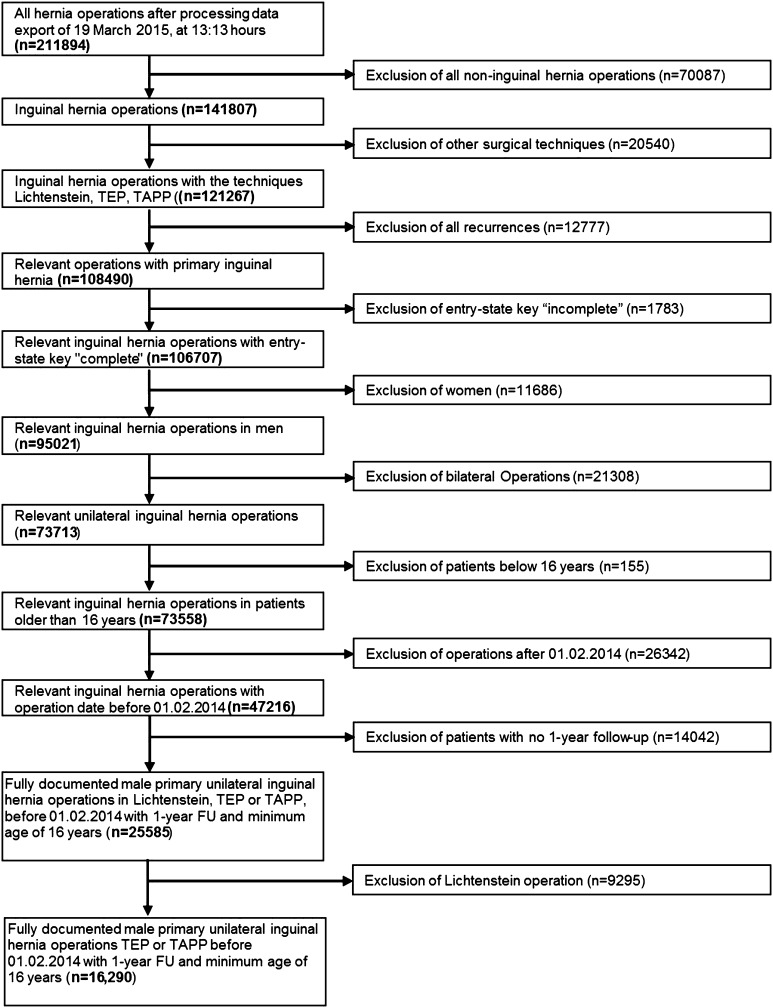

Inclusion criteria were minimum age of 16 years, male patient, primary unilateral inguinal hernia, TEP or TAPP techniques, and availability of data on one-year follow-up (Fig. 1). In total, 16,290 patients were enrolled between September 1, 2009, and February 1, 2014. Of the participating surgeons, 466 (87.6 %) surgeons had carried out fewer than 25 endoscopic/laparoscopic operations (low-volume surgeons) and 66 (12.4 %) surgeons with 25 or more operations (high-volume surgeons) per year (Table 1). The low-volume surgeons’ group had carried out 9482 (58.2 %), and the high-volume surgeons’ group 6808 (41.8 %) of the total number of endoscopic/laparoscopic procedures (Table 2). The surgeons with fewer than 25 procedures had performed on average 9.47 ± 5.99 operations, and the surgeons with 25 or more procedures 44.12 ± 21.41 operations.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient inclusion

Table 1.

Number of high- and low-volume surgeons

| Operations per surgeon and year | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | ≥25 | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Number of surgeons | 466 | 87.59 | 66 | 12.41 | 532 | 100.00 |

Table 2.

Total number of endoscopic/laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs and caseload per surgeon

| Operations per surgeon and year | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | ≥25 | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Number of endoscopic/laparoscopic operations depending on caseload | 9482 | 58.21 | 6808 | 41.79 | 16,290 | 100.00 |

The demographic and surgery-related parameters included age (years), BMI (kg/m2), ASA score (I–IV), proportion of medial, lateral, femoral, and scrotal EHS classification as well as the hernia defect size based on EHS classification (Grade I = <1.5 cm, Grade II = 1.5–3 cm, Grade III = >3 cm) [11]. Where an operation entailed several hernia classifications, the latter were summarized as having a “combined” status.

The risk factors included COPD, diabetes, cortisone, immunosuppression, nicotine abuse, coagulopathy or antithrombotic therapy based on antiplatelet or anticoagulant medication. Risk factors were dichotomized, i.e., “yes” if at least one risk factor was positive and “no” otherwise. The dependent variables were intra- and postoperative complication rates, reoperation rates due to postoperative complications, recurrence rates, and rates of pain at rest, pain on exertion, and chronic pain requiring treatment.

All analyses were performed with the software SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NY, USA) and intentionally calculated to a full level of 5 %, i.e., they were not corrected in respect of multiple tests, and each p value ≤0.05 represents a significant result. To discern differences between the groups in unadjusted analyses, Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical outcome variables, and the robust t test (Satterthwaite) for continuous variables.

To rule out any confounding of data caused by different patient characteristics, the results of unadjusted analyses were verified via multivariable analyses in which, in addition to the surgeon volume, other influence parameters were simultaneously reviewed.

Since the main focus of this analysis is on comparison of surgeon’s caseloads per year (<25/≥25), most of the descriptive statistical analyses in this paper are shown separately for the two groups. All categorical patient data are therefore presented in contingency tables as absolute and relative frequencies for these categories. For continuous data, the mean values and standard deviations are given.

The binary regression model for dichotomous target variables was used to identify the influence of the various factors in multivariable analysis. In addition to the surgeon’s caseload per year (<25/≥25), other potential influence parameters included: ASA score I, II, III, IV, defect size EHS classification I (<1.5 cm), II (1.5–3 cm), III (>3 cm), age, BMI, risk factors, and EHS classification (lateral, medial, scrotal, femoral). As a result, the odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95 % confidence intervals based on the Wald test are given for estimates. For influence variables with more than two categories, one of these values was used in each case as a reference category. For the continuous variable age (years), the 10-year odds ratio is given and for BMI (kg/m2) a 5-point odds ratio. The results are sorted on the basis of influence and presented in tabular form.

Results

Comparison of patient collective

With regard to age, patients operated on by surgeons with ≥25 procedures per year had a significantly higher age and were on average one year older (56.1 ± 15.3 vs. 57.1 ± 15.4 years, p < 0.001) (Table 3). As regards the BMI, no difference was identified between the patient collectives of surgeons with <25 and ≥25 endoscopic/laparoscopic procedures per year (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean age, BMI, and caseload per surgeon

| Operations per surgeon and year | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| <25 OP/year | ≥25 OP/year | ||

| Age (year) | |||

| Mean ± STD | 56.1 ± 15.3 | 57.1 ± 15.4 | <.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean ± STD | 25.8 ± 3.3 | 25.8 ± 3.4 | 0.757 |

For the unadjusted tests aimed at identifying a relationship between the caseloads per surgeon and year (<25/≥25) and the categorical influence variables, significant differences were noted for almost all influence variables. Low-volume surgeons operated more often on patients with a low ASA score (e.g., ASA I: 35.9 vs. 28.4 %) as well as with smaller defect sizes (EHS I = <1.5 cm: 15.4 vs. 10.6 %) (Table 4). On the other hand, high-volume surgeons had patients with higher ASA scores (e.g., ASA III/IV: 16.0 vs. 10.9 %), larger defect sizes (e.g., EHS III = >3 cm: 24.1 vs. 20.1 %) as well as scrotal EHS classification (4.3 vs. 1.9 %) (all p values <0.001).

Table 4.

Demographic, patient-related risk factors, and caseload per surgeon

| <25 OP/year | ≥25 OP/year | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| ASA score | |||||

| I | 3400 | 35.86 | 1935 | 28.42 | <.001 |

| II | 5051 | 53.27 | 3781 | 55.54 | |

| III/IV | 1031 | 10.87 | 1092 | 16.04 | |

| Defect size | |||||

| I (<1.5 cm) | 1458 | 15.38 | 722 | 10.61 | <.001 |

| II (1.5–3 cm) | 6122 | 64.56 | 4448 | 65.33 | |

| III (>3 cm) | 1902 | 20.06 | 1638 | 24.06 | |

| EHS classification medial | |||||

| Yes | 3355 | 35.38 | 2475 | 36.35 | 0.202 |

| No | 6127 | 64.62 | 4333 | 63.65 | |

| EHS classification lateral | |||||

| Yes | 7034 | 74.18 | 5103 | 74.96 | 0.264 |

| No | 2448 | 25.82 | 1705 | 25.04 | |

| EHS classification femoral | |||||

| Yes | 165 | 1.74 | 97 | 1.42 | 0.115 |

| No | 9317 | 98.26 | 6711 | 98.58 | |

| EHS classification scrotal | |||||

| Yes | 181 | 1.91 | 292 | 4.29 | <.001 |

| No | 9301 | 98.09 | 6516 | 95.71 | |

| Risk factor | |||||

| Total | |||||

| Yes | 2468 | 26.03 | 1518 | 22.30 | <.001 |

| No | 7014 | 73.97 | 5290 | 77.70 | |

| COPD | |||||

| Yes | 426 | 4.49 | 339 | 4.98 | 0.148 |

| No | 9056 | 95.51 | 6469 | 95.02 | |

| Diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 438 | 4.62 | 271 | 3.98 | 0.049 |

| No | 9044 | 95.38 | 6537 | 96.02 | |

| Aortic aneurysm | |||||

| Yes | 37 | 0.39 | 17 | 0.25 | 0.124 |

| No | 9445 | 99.61 | 6791 | 99.75 | |

| Immunosuppression | |||||

| Yes | 48 | 0.51 | 18 | 0.26 | 0.017 |

| No | 9434 | 99.49 | 6790 | 99.74 | |

| Corticoids | |||||

| Yes | 82 | 0.86 | 40 | 0.59 | 0.043 |

| No | 9400 | 99.14 | 6768 | 99.41 | |

| Smoking | |||||

| Yes | 1116 | 11.77 | 513 | 7.54 | <.001 |

| No | 8366 | 88.23 | 6295 | 92.46 | |

| Coagulopathy | |||||

| Yes | 105 | 1.11 | 82 | 1.20 | 0.566 |

| No | 9377 | 98.89 | 6726 | 98.80 | |

| Antiplatelet medication | |||||

| Yes | 558 | 5.88 | 454 | 6.67 | 0.041 |

| No | 8924 | 94.12 | 6354 | 93.33 | |

| Anticoagulation therapy | |||||

| Yes | 135 | 1.42 | 134 | 1.97 | 0.007 |

| No | 9347 | 98.58 | 6674 | 98.03 | |

In terms of the risk factors, global analysis, i.e., occurrence of at least one risk factor, also revealed a significant difference (Table 4). In total, 26.0 % of patients operated on by low-volume surgeons had at least one risk factor, while the proportion of those with at least one risk factor operated on by high-volume surgeons was only 22.3 % (p = 0.001). That effect was mainly attributable to the difference in the nicotine abuse rate (11.8 vs. 7.5 %; p < 0.001). The proportion of patients with antithrombotic therapy based on antiplatelet and anticoagulant treatment was significantly higher in the patient collectively operated on by the high-volume surgeons (Table 4).

Unadjusted analysis of outcomes by volume

Unadjusted analysis of the relationship between the caseload per surgeon and year did not show any significant difference in the overall intraoperative complication rate between <25 and ≥25 (p = 0.526, Table 5). However, surgeons with <25 endoscopic/laparoscopic procedures per year caused significantly more organ injuries, especially vascular injuries (p = 0.010, Table 5). As regards the overall postoperative complication rates, low-volume surgeons had, at 2.23 %, a significantly lower rate (p < 0.001) compared with the high-volume surgeons at 4.95 % (Table 5). That difference was mainly due to the significantly lower seroma rate in favor of the low-volume surgeons (0.91 vs. 4.20 %; p < 0.001). That may be due to the high proportion of inguinal hernias with EHS III (>3 cm) defect size and scrotal classification which was investigated in the subsequent multivariable analysis. No significant difference was found in the rate of postoperative complications, leading to reoperation, which was 0.94 % for the low-volume surgeons and 0.72 % for the high-volume surgeons (p = 0.133).

Table 5.

Unadjusted perioperative and 1-year follow-up outcomes and caseload per surgeon

| <25 OP/year | ≥25 OP/year | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Intraoperative complications | |||||

| Total | |||||

| Yes | 122 | 1.29 | 80 | 1.18 | 0.526 |

| No | 9360 | 98.71 | 6728 | 98.82 | |

| Bleeding | |||||

| Yes | 81 | 0.85 | 61 | 0.90 | 0.777 |

| No | 9401 | 99.15 | 6747 | 99.10 | |

| Injuries | |||||

| Total | |||||

| Yes | 72 | 0.76 | 29 | 0.43 | 0.008 |

| No | 9410 | 99.24 | 6779 | 99.57 | |

| Vascular | |||||

| Yes | 36 | 0.38 | 11 | 0.16 | 0.010 |

| No | 9446 | 99.62 | 6797 | 99.84 | |

| Bowel | |||||

| Yes | 11 | 0.12 | 4 | 0.06 | 0.235 |

| No | 9471 | 99.88 | 6804 | 99.94 | |

| Bladder | |||||

| Yes | 7 | 0.07 | 8 | 0.12 | 0.365 |

| No | 9475 | 99.93 | 6800 | 99.88 | |

| Postoperative complications | |||||

| Total | |||||

| Yes | 211 | 2.23 | 337 | 4.95 | <.001 |

| No | 9271 | 97.77 | 6471 | 95.05 | |

| Bleeding | |||||

| Yes | 109 | 1.15 | 49 | 0.72 | 0.006 |

| No | 9373 | 98.85 | 6759 | 99.28 | |

| Seroma | |||||

| Yes | 86 | 0.91 | 286 | 4.20 | <.001 |

| No | 9396 | 99.09 | 6522 | 95.80 | |

| Infection | |||||

| Yes | 11 | 0.12 | 2 | 0.03 | 0.053 |

| No | 9471 | 99.88 | 6806 | 99.97 | |

| Bowel injury/anastomotic leakage | |||||

| Yes | 1 | 0.01 | 3 | 0.04 | 0.178 |

| No | 9481 | 99.99 | 6805 | 99.96 | |

| Impaired wound healing | |||||

| Yes | 20 | 0.21 | 2 | 0.03 | 0.002 |

| No | 9462 | 99.79 | 6806 | 99.97 | |

| Ileus | |||||

| Yes | 2 | 0.02 | 2 | 0.03 | 0.739 |

| No | 9480 | 99.98 | 6806 | 99.97 | |

| Reoperation | |||||

| Yes | 89 | 0.94 | 49 | 0.72 | 0.133 |

| No | 9393 | 99.06 | 6759 | 99.28 | |

| Recurrence on follow-up | |||||

| Yes | 98 | 1.03 | 50 | 0.73 | 0.047 |

| No | 9384 | 98.97 | 6758 | 99.27 | |

| Pain at rest on follow-up | |||||

| Yes | 446 | 4.70 | 296 | 4.35 | 0.283 |

| No | 9036 | 95.30 | 6512 | 95.65 | |

| Pain on exertion on follow-up | |||||

| Yes | 887 | 9.35 | 525 | 7.71 | <.001 |

| No | 8595 | 90.65 | 6283 | 92.29 | |

| Pain requiring treatment | |||||

| Yes | 253 | 2.67 | 157 | 2.31 | 0.146 |

| No | 9229 | 97.33 | 6651 | 97.69 | |

Significant advantages were identified in the recurrence (0.73 vs. 1.03 %; p = 0.047) and in the pain on exertion (7.71 vs. 9.35 %; p < 0.001) rates in favor of the patient collective operated on by the high-volume surgeons on one-year follow-up (Table 5).

Multivariable analyses of outcome by volume

Intraoperative complications

The results obtained with the model used to investigate the effects of the variables related to patient and operation characteristics (caseload per year and surgeon, age, BMI, ASA score, defect size, hernia location as well as the presence of risk factors) on the occurrence of intraoperative complications are illustrated in Table 6 (model matching: p = 0.001). The risk of intraoperative complications was affected by scrotal (p = 0.011) and medial (p = 0.020) EHS classification. Scrotal EHS classification increased the risk of intraoperative complications [OR 2.212 (1.201; 4.073)]. By contrast, medial EHS classification reduced that complication risk [OR 0.577 (0.363; 0.916)].

Table 6.

Multivariable analysis of intraoperative complications

| Parameter | p value | Category | p value paired | OR estimate | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EHS classification scrotal | 0.011 | Yes versus no | 2.212 | 1.201 | 4.073 | |

| EHS classification medial | 0.020 | Yes versus no | 0.577 | 0.363 | 0.916 | |

| ASA score | 0.178 | I versus II | 0.074 | 0.715 | 0.495 | 1.033 |

| I versus III/IV | 0.129 | 0.660 | 0.386 | 1.129 | ||

| II versus III/IV | 0.708 | 0.923 | 0.607 | 1.403 | ||

| Caseload per surgeon and year | 0.275 | <25 versus ≥25 | 1.174 | 0.880 | 1.568 | |

| Age (10-year OR) | 0.427 | 1.045 | 0.937 | 1.165 | ||

| EHS classification femoral | 0.555 | Yes versus no | 0.654 | 0.160 | 2.678 | |

| BMI (5-point OR) | 0.719 | 1.038 | 0.848 | 1.270 | ||

| Defect size | 0.808 | I versus II | 0.903 | 0.972 | 0.618 | 1.530 |

| I versus III | 0.611 | 0.874 | 0.520 | 1.469 | ||

| II versus III | 0.541 | 0.899 | 0.638 | 1.265 | ||

| Risk factors | 0.878 | Yes versus no | 0.974 | 0.697 | 1.361 | |

| EHS classification lateral | 0.948 | Yes versus no | 1.017 | 0.611 | 1.691 | |

However, no evidence was found that an individual surgeon’s caseload (<25 vs. ≥25 endoscopic/laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs per year) influenced the intraoperative complication rate [OR 1.174 (0.880–1.568); p = 0.275].

Postoperative complications

The results obtained with the model used to investigate the postoperative complication rate are presented in Table 7 (model matching: p < 0.001). The risk of postoperative complications was negatively impacted by high-volume surgeons, scrotal hernias, higher age, and larger defects. That risk declined when a surgeon had performed fewer than 25 procedures per year [OR 0.463 (0.388; 0.554); p < 0.001]. Scrotal EHS classification increased the risk of occurrence of a postoperative complication [OR 2.076 (1.444; 2.984); p < 0.001]. Equally, a higher age [10-year OR 1.114 (1.041; 1.192); p = 0.002] increased the postoperative complication rate. Finally, the presence of a smaller defect size reduced the postoperative complication rate [I vs. II: OR 0.700 (0.505; 0.970); p = 0.032. I vs. III: OR 0.580 (0.406; 0.830); p = 0.003].

Table 7.

Multivariable analysis of postoperative complications

| Parameter | p value | Category | p value paired comparison | OR estimate | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caseload per surgeon and year | <.001 | <25 versus ≥ 25 | 0.463 | 0.388 | 0.554 | |

| EHS classification lateral | <.001 | Yes versus no | 0.471 | 0.350 | 0.633 | |

| BMI (5-point OR) | <.001 | 0.746 | 0.649 | 0.858 | ||

| EHS classification scrotal | <.001 | Yes versus no | 2.076 | 1.444 | 2.984 | |

| EHS classification medial | <.001 | Yes versus no | 0.566 | 0.423 | 0.758 | |

| Age (10-year OR) | 0.002 | 1.114 | 1.041 | 1.192 | ||

| Defect size | 0.010 | I versus II | 0.032 | 0.700 | 0.505 | 0.970 |

| I versus III | 0.003 | 0.580 | 0.406 | 0.830 | ||

| II versus III | 0.072 | 0.829 | 0.676 | 1.017 | ||

| ASA score | 0.092 | I versus II | 0.764 | 1.035 | 0.827 | 1.295 |

| I versus III/IV | 0.135 | 0.786 | 0.573 | 1.078 | ||

| II versus III/IV | 0.029 | 0.759 | 0.593 | 0.972 | ||

| Risk factors | 0.761 | Yes versus no | 1.033 | 0.838 | 1.273 | |

| EHS classification femoral | 0.990 | Yes versus no | 0.996 | 0.516 | 1.921 | |

Likewise, medial and lateral EHS classification and higher BMI reduced the risk of postoperative complications. Lateral [OR 0.471 (0.350; 0.633); p < 0.001] or medial EHS classification [OR 0.566 (0.423; 0.758); p < 0.001] as well as a five-point higher BMI [five-point OR 0.746 (0.649; 0.858); p < 0.001] reduced the postoperative complication rate.

Recurrence

Table 8 presents the results of multivariable analysis of factors impacting recurrence on one-year follow-up (model matching: p = 0.001). BMI proved to be the strongest influence factor (p = 0.004). A five-point higher BMI increased the recurrence rate [five-point OR 1.342 (1.098; 1.640)]. Likewise, medial EHS classification significantly increased the recurrence rate [OR 1.690 (1.077; 2.652); p = 0.022]. The surgical volume of the individual surgeons also had a significant influence on the risk (p = 0.023). Surgeons with <25 endoscopic/laparoscopic operations per year had a higher recurrence rate [OR 1.494 (1.056; 2.115); p = 0.023]. With a prevalence of 0.9 %, this would correspond to 11 recurrences for 1000 operations by surgeons with <25 endoscopic/laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs per year compared to seven recurrences for ≥25 operations per year.

Table 8.

Multivariable analysis of recurrence

| Parameter | p value | Category | p value paired comparison | OR estimate | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (5-point OR) | 0.004 | 1.342 | 1.098 | 1.640 | ||

| EHS classification medial | 0.022 | Yes versus no | 1.690 | 1.077 | 2.652 | |

| Caseload per surgeon and year | 0.023 | <25 versus ≥25 | 1.494 | 1.056 | 2.115 | |

| ASA score | 0.090 | I versus II | 0.195 | 0.758 | 0.498 | 1.152 |

| I versus III/IV | 0.028 | 0.510 | 0.279 | 0.931 | ||

| II versus III/IV | 0.103 | 0.673 | 0.418 | 1.083 | ||

| EHS classification scrotal | 0.173 | Yes versus no | 1.779 | 0.777 | 4.073 | |

| Age (10-year OR) | 0.342 | 0.940 | 0.828 | 1.068 | ||

| Defect size | 0.532 | I versus II | 0.315 | 1.273 | 0.795 | 2.039 |

| I versus III | 0.724 | 1.105 | 0.636 | 1.921 | ||

| II versus III | 0.488 | 0.868 | 0.581 | 1.296 | ||

| EHS classification femoral | 0.735 | Yes versus no | 1.221 | 0.383 | 3.894 | |

| EHS classification lateral | 0.777 | Yes versus no | 0.935 | 0.586 | 1.491 | |

| Risk factors | 0.996 | Yes versus no | 1.001 | 0.680 | 1.474 | |

Pain at rest

Analysis of the results obtained on investigating pain at rest on one-year follow-up is illustrated in Table 9 (model matching: p < 0.001). The defect size proved to be the strongest influence factor here (p < 0.001). A small defect size increased the risk of pain at rest on follow-up [I vs. II: OR 1.671 (1.382; 2.022); I vs. III: OR 2.205 (1.702; 2.857); II vs. III: OR 1.319 (1.065; 1.634); p = 0.011]. Equally, BMI and age had a highly significant impact on pain at rest (in each case p < 0.001). A five-point higher BMI increased pain at rest [five-point OR 1.230 (1.114; 1.359)]. Conversely, higher age [10-year OR 0.890 (0.841; 0.941)] reduced the risk of pain at rest. Finally, femoral EHS classification increased the risk of pain at rest [OR 1.772 (1.106; 2.839); p = 0.017]. The number of surgical procedures performed by a surgeon per year did not impact the risk of onset of pain at rest.

Table 9.

Multivariable analysis of pain at rest

| Parameter | p value | Category | p value paired | OR estimate | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defect size | <.001 | I versus II | <.001 | 1.671 | 1.382 | 2.022 |

| I versus III | <.001 | 2.205 | 1.702 | 2.857 | ||

| II versus III | 0.011 | 1.319 | 1.065 | 1.634 | ||

| BMI (5-point OR) | <.001 | 1.230 | 1.114 | 1.359 | ||

| Age (10-year OR) | <.001 | 0.890 | 0.841 | 0.941 | ||

| EHS classification femoral | 0.017 | Yes versus no | 1.772 | 1.106 | 2.839 | |

| ASA score | 0.072 | I versus II | 0.035 | 0.822 | 0.685 | 0.986 |

| I versus III/IV | 0.056 | 0.751 | 0.559 | 1.008 | ||

| II versus III/IV | 0.473 | 0.913 | 0.713 | 1.170 | ||

| EHS classification lateral | 0.231 | Yes versus no | 1.164 | 0.908 | 1.491 | |

| Risk factors | 0.267 | Yes versus no | 1.107 | 0.925 | 1.323 | |

| Caseload per surgeon and year | 0.516 | <25 versus ≥25 | 1.052 | 0.903 | 1.226 | |

| EHS classification medial | 0.785 | Yes versus no | 1.031 | 0.827 | 1.286 | |

| EHS classification scrotal | 0.868 | Yes versus no | 1.043 | 0.632 | 1.722 | |

Pain on exertion

Analysis of the results obtained on investigating pain on exertion on one-year follow-up is summarized in Table 10 (model matching: p < 0.001). Pain on exertion was significantly and negatively influenced by the defect size, BMI, and caseload of <25 procedures per surgeon and year. The risk of pain on exertion increased for smaller defect sizes [I vs. II: OR 1.358 (1.173; 1.572); p < 0.001; I vs. III: OR 1.673 (1.376; 2.035); p < 0.001; II vs. III: OR 1.232 (1.053; 1.443); p = 0.009] and for a five-point higher BMI [five-point OR 1.179 (1.092; 1.272); p < 0.001]. Likewise, a caseload <25 procedures per year significantly increased the risk of onset of pain on exertion [OR 1.191 (1.062; 1.337); p = 0.003]. A higher age [10-year OR 0.772 (0.741; 0.804); p < 0.001] reduced onset of pain on exertion.

Table 10.

Multivariable analysis of pain on exertion

| Parameter | p value | Category | p value paired comparison | OR estimate | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (10-year OR) | <.001 | 0.772 | 0.741 | 0.804 | ||

| Defect size | <.001 | I versus II | <.001 | 1.358 | 1.173 | 1.572 |

| I versus III | <.001 | 1.673 | 1.376 | 2.035 | ||

| II versus III | 0.009 | 1.232 | 1.053 | 1.443 | ||

| BMI (5-point OR) | <.001 | 1.179 | 1.092 | 1.272 | ||

| Caseload per surgeon and year | 0.003 | <25 versus ≥25 | 1.191 | 1.062 | 1.337 | |

| ASA score | 0.086 | I versus II | 0.036 | 0.869 | 0.761 | 0.991 |

| I versus III/IV | 0.097 | 0.823 | 0.655 | 1.036 | ||

| II versus III/IV | 0.600 | 0.948 | 0.777 | 1.157 | ||

| Risk factors | 0.168 | Yes versus np | 1.100 | 0.961 | 1.259 | |

| EHS classification medial | 0.547 | Yes versus no | 1.053 | 0.890 | 1.247 | |

| EHS classification femoral | 0.719 | Yes versus no | 1.082 | 0.703 | 1.666 | |

| EHS classification lateral | 0.854 | Yes versus no | 1.018 | 0.845 | 1.226 | |

| EHS classification scrotal | 0.951 | Yes versus no | 1.012 | 0.696 | 1.472 | |

Chronic pain requiring treatment

The results obtained on investigating chronic pain requiring treatment are presented in Table 11 (model matching: p < 0.001). The hernia defect size proved to be the strongest influence factor here (p < 0.001). A smaller defect size increased the risk of onset of chronic pain requiring treatment on follow-up [I vs. II: OR 2.084 (1.642; 2.644); I vs. III: OR 2.567 (1.832; 3.597)]. Equally, age and BMI had a highly significant effect on chronic pain requiring treatment (p < 0.001). Higher age [10-year OR 0.810 (0.752; 0.872)] reduced onset of chronic pain requiring treatment. A five-point higher BMI increased the risk of pain [five-point OR 1.339 (1.183; 1.516)].

Table 11.

Multivariable analysis of pain requiring treatment

| Parameter | p value | Category | p value paired | OR estimate | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defect size | <.001 | I versus II | <.001 | 2.084 | 1.642 | 2.644 |

| I versus III | <.001 | 2.567 | 1.832 | 3.597 | ||

| II versus III | 0.162 | 1.232 | 0.919 | 1.651 | ||

| Age (10-year OR) | <.001 | 0.810 | 0.752 | 0.872 | ||

| BMI (5-point OR) | <.001 | 1.339 | 1.183 | 1.516 | ||

| ASA score | 0.095 | I versus II | 0.199 | 0.855 | 0.673 | 1.086 |

| I versus III/IV | 0.030 | 0.652 | 0.442 | 0.960 | ||

| II versus III/IV | 0.105 | 0.762 | 0.549 | 1.059 | ||

| Risk factors | 0.144 | Yes versus no | 1.192 | 0.942 | 1.509 | |

| Operation (OR/year) | 0.326 | <25 versus ≥25 | 1.108 | 0.903 | 1.361 | |

| EHS classification femoral | 0.352 | Yes versus no | 1.386 | 0.698 | 2.752 | |

| EHS classification lateral | 0.389 | Yes versus no | 1.159 | 0.828 | 1.622 | |

| EHS classification scrotal | 0.633 | Yes versus no | 1.170 | 0.615 | 2.225 | |

| EHS classification medial | 0.964 | Yes versus no | 1.007 | 0.746 | 1.359 | |

Discussion

The learning curve associated with endoscopic/laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery requiring 50–100 procedures is longer than that involving the open Lichtenstein operation [1]. Under the supervision of experienced laparoscopic surgeons, young trainees can master the learning curve with good results [12]. Apart from the learning curve, other aspects increasingly discussed in surgery are the impact of the caseload of the treating institution and of the individual surgeon. In the hernia surgery setting, this topic has been addressed so far in three studies on, in each case, open incisional hernia surgery [13], open inguinal hernia surgery [8], and endoscopic inguinal hernia surgery in TEP technique [9]. All three studies identified a significant relationship between the individual surgeon’s caseload per year and patient outcome.

In the present paper, the results obtained for perioperative complications and 1-year follow-up of endoscopic/laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery based on data from the Herniamed Registry were analyzed to ascertain whether the number of operations per surgeon and year (<25 vs. ≥25) impacted the outcome. Differences were identified first of all on comparing the patient collectives undergoing surgery. The high-volume surgeons (≥25 operations per year) operated on significantly more patients with higher ASA score, larger defect size, and scrotal hernia. Likewise, patients operated on by the high-volume surgeons had received significantly more often effective treatment with platelet aggregation inhibitors and coumarin derivatives.

Overall, patients operated on by high-volume surgeons had thus a significantly higher risk profile with, accordingly, significantly more postoperative complications observed in the patients operated on by high-volume surgeons. That this, nonetheless, did not result in more postoperative complications requiring reoperation, but rather in a higher rate of seromas amenable to conservative treatment, attesting to the skill of experienced surgeons in mastering their patients’ higher-risk profile. The greater proportion of seromas in the patient group treated by the high-volume surgeons can also be explained by the significantly larger proportion of Grade III hernias (defect size >3 cm) and scrotal hernias. Apart from that, in patients operated on by low-volume surgeons (<25 operations per year), there were significantly more cases of secondary bleeding and impaired wound healing, but at 1.15 versus 0.72 and 0.21 versus 0.03 %, respectively, that difference was very small.

Univariable analysis of the findings on 1-year follow-up revealed that patients operated on by the low-volume surgeons had a significantly higher recurrence rate and pain on exertion rate but here, too, the differences at 1.03 versus 0.73 and 9.35 versus 7.71 %, respectively, were small. Univariable analysis of data for pain at rest and chronic pain requiring treatment did not reveal any differences.

Multivariable analysis revealed that scrotal hernia and large defect size had a significant influence on onset of a postoperative complication. The risk of occurrence of a postoperative complication was less in association with medial or lateral EHS classification, higher BMI value and, interestingly, for surgeons with a caseload of fewer than 25 operations per year. The only explanation that can be given for the latter finding is that surgeons with fewer than 25 procedures per year generally had operated on patients with a lower-risk profile.

Multivariable analysis of the influence variables impacting recurrence showed that higher BMI, medial EHS classification, and a caseload of fewer than 25 procedures per year were associated with a higher risk.

Pain at rest was revealed by multivariable analysis to be negatively affected by a smaller defect size, higher BMI value, and femoral EHS classification. Older patients were found to have a lower risk of onset of pain at rest.

Likewise, multivariable analysis showed that onset of pain on exertion was negatively influenced by smaller defect size, higher BMI value, and additionally by a caseload of fewer than 25 surgical procedures per year. Higher age was also found to be associated with a lower risk of pain on exertion.

Equally, chronic pain requiring treatment was negatively impacted by a smaller hernia defect and higher BMI, with here, too, a lower risk in older patients. The caseload per year did not affect that outcome criterion.

As such, the registry data presented in this paper for endoscopic/laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery confirm that the annual caseload of the individual surgeons exerted a certain amount of influence on the outcome but the differences were not as pronounced as in the publication by the Mayo Clinic [9]. This is no doubt due to the fact that in the German system even trained surgeons who have less experience of a surgical technique work under the supervision of an experienced surgeon, thus assuring that in such settings, too, good results can be achieved [12]. Based on the experience of the surgeon, also of the trained surgeon, the Chairman of a Department of Surgery decides whether the surgeon can perform the operation alone or under the guidance of a more experienced colleague. The registry does not, of course, provide any information on the actual experience of individual surgeons. It must also be borne in mind that unlike the National Danish and Swedish Registries the data in the Herniamed Registry are collected only from hospitals with a special interest in hernia surgery. Furthermore, the high-volume surgeons were responsible for the more difficult cases, i.e., more advanced hernias. The difference would have probably been much greater if the study had been randomized.

In summary, it can be stated that with regard to the quality parameters recurrence rate and pain on exertion, a “low-volume surgeon” achieves slightly worse results than a “high-volume” surgeon, but overall can assure a high-quality level in endoscopic/laparoendoscopic inguinal hernia surgery. The preconditions for a good outcome, also in routine clinical settings and, in particular, for trainee surgeons or surgeons with lower annual caseloads, are the use of a standardized technique, a structured training program, and close supervision of trainees and of surgeons with lower caseloads.

Acknowledgments

Ferdinand Köckerling—Grants to fund the Herniamed Registry from Johnson & Johnson, Norderstedt, Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, pfm medical, Cologne, Dahlhausen, Cologne, B Braun, Tuttlingen, MenkeMed, Munich and Bard, Karlsruhe.

Herniamed Study Group

Scientific Board: Köckerling, Ferdinand (Chairman) (Berlin); Bittner, Reinhard (Rottenburg); Fortelny, René (Wien); Jacob, Dietmar (Berlin); Koch, Andreas (Cottbus); Kraft, Barbara (Stuttgart); Kuthe, Andreas (Hannover); Lippert, Hans (Magdeburg): Lorenz, Ralph (Berlin); Mayer, Franz (Salzburg); Moesta, Kurt Thomas (Hannover); Niebuhr, Henning (Hamburg); Peiper, Christian (Hamm); Pross, Matthias (Berlin); Reinpold, Wolfgang (Hamburg); Simon, Thomas (Weinheim); Stechemesser, Bernd (Köln); Unger, Solveig (Chemnitz). Participants: Ahmetov, Azat (Saint-Petersburg); Alapatt, Terence Francis (Frankfurt/Main); Amann, Stefan (Neuendettelsau); Anders, Stefan (Berlin); Anderson, Jürina (Würzburg); Arndt, Anatoli (Elmshorn); Asperger, Walter (Halle); Avram, Iulian (Saarbrücken); Bandowsky, Boris (Damme); Barkus; Jörg (Velbert); Becker, Matthias (Freital); Behrend, Matthias (Deggendorf); Beuleke, Andrea (Burgwedel); Berger, Dieter (Baden-Baden); Bittner, Reinhard (Rottenburg); Blaha, Pavel (Zwiesel); Blumberg, Claus (Lübeck); Böckmann, Ulrich (Papenburg); Böhle, Arnd Steffen (Bremen); Böttger, Thomas Carsten (Fürth); Bolle, Ludger (Berlin); Borchert, Erika (Grevenbroich); Born, Henry (Leipzig); Brabender, Jan (Köln); Brauckmann, Markus (Rüdesheim am Rhein); Breitenbuch von, Philipp (Radebeul); Brüggemann, Armin (Kassel); Brütting, Alfred (Erlangen); Budzier, Eckhard (Meldorf); Burchett, Bert (Waren); Burghardt, Jens (Rüdersdorf); Carus, Thomas (Bremen); Cejnar, Stephan-Alexander (München); Chirikov, Ruslan (Dorsten); Claußnitzer, Christian (Ulm); Comman, Andreas (Bogen); Crescenti, Fabio (Verden/Aller); Daniels, Thies (Hamburg); Dapunt, Emanuela (Bruneck); Decker, Georg (Berlin); Demmel, Michael (Arnsberg); Descloux, Alexandre (Baden); Deusch, Klaus-Peter (Wiesbaden); Dick, Marcus (Neumünster); Dieterich, Klaus (Ditzingen); Dietz, Harald (Landshut); Dittmann, Michael (Northeim); Dornbusch, Jan (Herzberg/Elster); Drummer, Bernhard (Forchheim); Eckermann, Oliver (Luckenwalde); Eckhoff, Jörn/Hamburg); Elger, Karlheinz (Germersheim); Engelhardt, Thomas (Erfurt); Erichsen, Axel (Friedrichshafen); Eucker, Dietmar (Bruderholz); Fackeldey, Volker (Kitzingen); Farke, Stefan (Delmenhorst); Faust, Hendrik (Emden); Federmann, Georg (Seehausen); Feichter, Albert (Wien); Fiedler, Michael (Eisenberg); Fischer, Ines (Wiener Neustadt); Fleischer, Sabine (Dinslaken); Fortelny, René H. (Wien); Franczak, Andreas (Wien); Franke, Claus (Düsseldorf); Frankenberg von, Moritz (Salem); Frehner, Wolfgang (Ottobeuren); Friedhoff, Klaus (Andernach); Friedrich, Jürgen (Essen); Frings, Wolfram (Bonn); Fritsche, Ralf (Darmstadt); Frommhold, Klaus (Coesfeld); Frunder, Albrecht (Tübingen); Fuhrer, Günther (Reutlingen); Gassler, Harald (Villach); Gawad, Karim A. Frankfurt/Main); Gerdes, Martin (Ostercappeln); Germanov, German (Halberstadt; Gilg, Kai-Uwe (Hartmannsdorf); Glaubitz, Martin (Neumünster); Glauner-Goldschmidt, Kerstin (Werne); Glutig, Holger (Meissen); Gmeiner, Dietmar (Bad Dürrnberg); Göring, Herbert (München); Grebe, Werner (Rheda-Wiedenbrück); Grothe, Dirk (Melle); Gürtler, Thomas (Zürich); Hache, Helmer (Löbau); Hämmerle, Alexander (Bad Pyrmont); Haffner, Eugen (Hamm); Hain, Hans-Jürgen (Gross-Umstadt); Hammans, Sebastian (Lingen); Hampe, Carsten (Garbsen); Harrer, Petra (Starnberg); Hartung, Peter (Werne); Heinzmann, Bernd (Magdeburg); Heise, Joachim Wilfried (Stolberg); Heitland, Tim (München); Helbling, Christian (Rapperswil); Hempen, Hans-Günther (Cloppenburg); Henneking, Klaus-Wilhelm (Bayreuth); Hennes, Norbert (Duisburg); Hermes, Wolfgang (Weyhe); Herrgesell, Holger (Berlin); Herzing, Holger Höchstadt); Hessler, Christian (Bingen); Hildebrand, Christiaan (Langenfeld); Höferlin, Andreas (Mainz); Hoffmann, Henry (Basel); Hoffmann, Michael (Kassel); Hofmann, Eva M. (Frankfurt/Main); Hopfer, Frank (Eggenfelden); Hornung, Frederic (Wolfratshausen); Hügel, Omar (Hannover); Hüttemann, Martin (Oberhausen); Huhn, Ulla (Berlin); Hunkeler, Rolf (Zürich); Imdahl, Andreas (Heidenheim); Jacob, Dietmar (Berlin); Jenert, Burghard (Lichtenstein); Jugenheimer, Michael (Herrenberg); Junger, Marc (München); Kaaden, Stephan (Neustadt am Rübenberge); Käs, Stephan (Weiden); Kahraman, Orhan (Hamburg); Kaiser, Christian (Westerstede); Kaiser, Stefan (Kleinmachnow); Kapischke, Matthias (Hamburg); Karch, Matthias (Eichstätt); Kasparek, Michael S. (München); Keck, Heinrich (Wolfenbüttel); Keller, Hans W. (Bonn); Kienzle, Ulrich (Karlsruhe); Kipfmüller, Brigitte (Köthen); Kirsch, Ulrike (Oranienburg); Klammer, Frank (Ahlen); Klatt, Richard (Hagen); Kleemann, Nils (Perleberg); Klein, Karl-Hermann (Burbach); Kleist, Sven (Berlin); Klobusicky, Pavol (Bad Kissingen); Kneifel, Thomas (Datteln); Knoop, Michael (Frankfurt/Oder); Knotter, Bianca (Mannheim); Koch, Andreas (Cottbus); Koch, Andreas (Münster); Köckerling, Ferdinand (Berlin); Köhler, Gernot (Linz); König, Oliver (Buchholz); Kornblum, Hans (Tübingen); Krämer, Dirk (Bad Zwischenahn); Kraft, Barbara (Stuttgart); Kreissl, Peter (Ebersberg); Krones, Carsten Johannes (Aachen); Kruse, Christinan (Aschaffenburg); Kube, Rainer (Cottbus); Kühlberg, Thomas (Berlin); Kuhn, Roger (Gifhorn); Kusch, Eduard (Gütersloh); Kuthe, Andreas (Hannover); Ladberg, Ralf (Bremen); Ladra, Jürgen (Düren); Lahr-Eigen, Rolf (Potsdam); Lainka, Martin (Wattenscheid); Lammers, Bernhard J. (Neuss); Lancee, Steffen (Alsfeld); Lange, Claas (Berlin); Langer, Claus (Göttingen); Laps, Rainer (Ehringshausen); Larusson, Hannes Jon (Pinneberg); Lauschke, Holger (Duisburg); Leher, Markus (Schärding); Leidl, Stefan (Waidhofen/Ybbs); Lenz, Stefan (Berlin); Lesch, Alexander (Kamp-Lintfort); Liedke, Marc Olaf (Heide); Lienert, Mark (Duisburg); Limberger, Andreas (Schrobenhausen); Limmer, Stefan (Würzburg); Locher, Martin (Kiel); Loghmanieh, Siawasch (Viersen); Lorenz, Ralph (Berlin); Luther, Stefan (Wipperfürth); Mallmann, Bernhard (Krefeld); Manger, Regina (Schwabmünchen); Maurer, Stephan (Münster); Mayer, Franz (Salzburg); Mayer, Jens (Schwäbisch Gmünd); Mellert, Joachim (Höxter); Menzel, Ingo (Weimar); Meurer, Kirsten (Bochum); Meyer, Moritz (Ahaus); Mirow, Lutz (Kirchberg); Mittenzwey, Hans-Joachim (Berlin); Mörder-Köttgen, Anja (Freiburg); Moesta, Kurt Thomas (Hannover); Moldenhauer, Ingolf (Braunschweig); Morkramer, Rolf (Xanten); Mosa, Tawfik (Merseburg); Müller, Hannes (Schlanders); Münzberg, Gregor (Berlin); Mussack, Thomas (St. Gallen); Nasifoglu, Bernd (Ehingen); Neumann, Jürgen (Haan); Neumeuer, Kai (Paderborn); Niebuhr, Henning (Hamburg); Nix, Carsten (Walsrode); Nölling, Anke (Burbach); Nostitz, Friedrich Zoltán (Mühlhausen); Obermaier, Straubing); Öz-Schmidt, Meryem (Hanau); Oldorf, Peter (Usingen); Olivieri, Manuel (Pforzheim); Passon, Marius (Freudenberg); Pawelzik, Marek (Hamburg); Peiper, Christian (Hamm); Peiper, Matthias (Essen); Peitgen, Klaus (Bottrop); Pertl, Alexander (Spittal/Drau); Philipp, Mark (Rostock); Pickart, Lutz (Bad Langensalza); Pizzera, Christian (Graz); Pöllath, Martin (Sulzbach-Rosenberg); Possin, Ulrich (Laatzen); Prenzel, Klaus (Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler); Pröve, Florian (Goslar); Pronnet, Thomas (Fürstenfeldbruck); Pross, Matthias (Berlin); Puff, Johannes (Dinkelsbühl); Rabl, Anton (Passau); Rapp, Martin (Neunkirchen); Reck, Thomas (Püttlingen); Reinpold, Wolfgang (Hamburg); Reuter, Christoph (Quakenbrück); Richter, Jörg (Winnenden); Riemann, Kerstin (Alzenau-Wasserlos); Rodehorst, Anette (Otterndorf); Roehr, Thomas (Rödental); Roncossek, Bremerhaven); Roth Hartmut (Nürnberg); Sardoschau, Nihad (Saarbrücken); Sauer, Gottfried (Rüsselsheim); Sauer, Jörg (Arnsberg); Seekamp, Axel (Freiburg); Seelig, Matthias (Bad Soden); Seidel, Hanka (Eschweiler); Seiler, Christoph Michael (Warendorf); Seltmann, Cornelia (Hachenburg); Senkal, Metin (Witten); Shamiyeh, Andreas (Linz); Shang, Edward (München); Siemssen, Björn (Berlin); Sievers, Dörte (Hamburg); Silbernik, Daniel (Bonn); Simon, Thomas (Sinsheim); Sinn, Daniel (Olpe); Sinning, Frank (Nürnberg); Smaxwil, Constatin Aurel (Stuttgart); Syga, Günter (Bayreuth); Schabel, Volker (Kirchheim/Teck); Schadd, Peter (Euskirchen); Schassen von, Christian (Hamburg); Schattenhofer, Thomas (Vilshofen); Scheidbach, Hubert (Neustadt/Saale); Schelp, Lothar (Wuppertal); Scherf, Alexander (Pforzheim); Scheyer, Mathias (Bludenz); Schilling, André (Kamen); Schimmelpenning, Hendrik (Neustadt in Holstein); Schinkel, Svenja (Kempten); Schmid, Michael (Gera); Schmid, Thomas (Innsbruck); Schmidt, Rainer (Paderborn); Schmidt, Sven-Christian (Berlin); Schmidt, Ulf (Mechernich); Schmitz, Heiner (Jena); Schmitz, Ronald (Altenburg); Schöche, Jan (Borna); Schoenen, Detlef (Schwandorf); Schrittwieser, Rudolf/Bruck an der Mur); Schroll, Andreas (München); Schultz, Christian (Bremen-Lesum); Schultz, Harald (Landstuhl); Schulze, Frank P. Mülheim an der Ruhr); Schumacher, Franz-Josef (Oberhausen); Schwab, Robert (Koblenz); Schwandner, Thilo (Lich); Schwarz, Jochen Günter (Rottenburg); Schymatzek, Ulrich (Radevormwald); Spangenberger, Wolfgang (Bergisch-Gladbach); Sperling, Peter (Montabaur); Staade, Katja (Düsseldorf); Staib, Ludger (Esslingen); Stamm, Ingrid (Heppenheim); Stark, Wolfgang (Roth); Stechemesser, Bernd (Köln); Steinhilper, Uz (München); Stengl, Wolfgang (Nürnberg); Stern, Oliver (Hamburg); Stöltzing, Oliver (Meißen); Stolte, Thomas (Mannheim); Stopinski, Jürgen (Schwalmstadt); Stubbe, Hendrik (Güstrow/); Stülzebach, Carsten (Friedrichroda); Tepel, Jürgen (Osnabrück); Terzić, Alexander (Wildeshausen); Teske, Ulrich (Essen); Thews, Andreas (Schönebeck); Tichomirow, Alexej (Brühl); Tillenburg, Wolfgang (Marktheidenfeld); Timmermann, Wolfgang (Hagen); Tomov, Tsvetomir (Koblenz; Train, Stefan H. (Gronau); Trauzettel, Uwe (Plettenberg); Triechelt, Uwe (Langenhagen); Ulcar, Heimo (Schwarzach im Pongau); Unger, Solveig (Chemnitz); Verweel, Rainer (Hürth); Vogel, Ulrike (Berlin); Voigt, Rigo (Altenburg); Voit, Gerhard (Fürth); Volkers, Hans-Uwe (Norden); Vossough, Alexander (Neuss); Wallasch, Andreas (Menden); Wallner, Axel (Lüdinghausen); Warscher, Manfred (Lienz); Warwas, Markus (Bonn); Weber, Jörg (Köln); Weihrauch, Thomas (Ilmenau); Weiß, Johannes (Schwetzingen); Weißenbach, Peter (Neunkirchen); Werner, Uwe (Lübbecke-Rahden); Wessel, Ina (Duisburg); Weyhe, Dirk (Oldenburg); Wieber, Isabell (Köln); Wiesmann, Aloys (Rheine); Wiesner, Ingo (Halle); Withöft, Detlef (Neutraubling); Woehe, Fritz (Sanderhausen); Wolf, Claudio (Neuwied); Yaksan, Arif (Wermeskirchen); Yildirim, Selcuk (Berlin); Zarras, Konstantinos (Düsseldorf); Zeller, Johannes (Waldshut-Tiengen); Zhorzel, Sven (Agatharied); Zuz, Gerhard (Leipzig).

Compliance with ethical standards

Disclosures

R. Bittner, B. Kraft, M. Hukauf, A. Kuthe, C. Schug-Pass have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Contributor Information

F. Köckerling, Email: ferdinand.koeckerling@vivantes.de

R. Bittner, Email: hernienzentrum@winghofer-medicum.de

B. Kraft, Email: kraft@diak-stuttgart.de

M. Hukauf, Email: martin.hukauf@statconsult.de

A. Kuthe, Email: AKuthe@Clementinenhaus.de

References

- 1.Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M, Bouillot JL, Campanelli G, Conze J, de Lange D, Fortelny R, Heikkinen T, Kingsnorth A, Kukleta J, Morales-Conde S, Nordin P, Schumpelick V, Smedberg S, Smietanski M, Weber G, Miserez M. European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia. 2009;13:343–403. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0529-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miserez M, Peeters E, Aufenacker T, Bouillot JL, Campanelli G, Conze J, Fortelny R, Heikkinen T, Jorgensen LN, Kukleta J, Morales-Conde S, Nordin P, Schumpelick V, Smedberg S, Smietanski M, Weber G, Simons MP. Update with level 1 studies of the European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia. 2014;18:151–163. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poelman MM, van den Heuvel B, Deelder JD, Abis GSA, Beudeker N, Bittner R, Campanelli G, van Dam D, Dwars BJ, Eker HH, Fingerhut A, Khatkov I, Koeckerling F, Kukleta JF, Miserez M, Montgomery A, Munoz Brands RM, Morales Conde S, Muysoms FE, Soltes M, Tromp W, Yavuz Y, Bonjer HJ. EAES consensus development conference on endoscopic repair of groin hernias. Surg Endosc. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bittner R, Arregui ME, Bisgaard T, Dudai M, Ferzli GS, Fitzgibbons RJ, Fortelny RH, Klinge U, Köckerling F, Kuhry E, Kukleta J, Lomanto D, Misra MC, Montgomery A, Morales-Conde S, Reinpold W, Rosenberg J, Sauerland S, Schug-Pass C, Singh K, Timoney M, Weyhe D, Chowbey P. Guidelines for laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal Hernia [International Endohernia Society (IEHS)] Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2773–2843. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1799-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bittner R, Montgomery A, Arregui E, Bansal V, Bingener J, Bisgaard T, Buhck H, Dudai M, Ferzli GS, Fitzgibbons RJ, Fortelny RH, Grimes KL, Klinge U, Koeckerling F, Kumar S, Kukleta J, Lomanto D, Misra MC, Morales-Conde S, Reinpold W, Rosenberg J, Singh K, Timoney M, Weyhe D, Chowbey P. Update of guidelines on laparoscopic (TAPP) und endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia (International Endohernia Society) Surg Endosc. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3917-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andresen K, Friis-Andresen H, Rosenberg J. Laparoscopic repair of primary inguinal hernia performed in public hospitals or low-volume centers have increased risk of reoperation for recurrence. Surg Innov. 2015;23(2):142–147. doi: 10.1177/1553350615596636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordin P. Volume of procedures and risk of recurrence after repair of groin hernia: national register study. BMJ. 2008 doi: 10.1136/bmj.39525.514572.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aquina CT, Probst CP, Kelly KN, Iannuzzi JC, Noyes K, Fleming FJ, Monson JR. The pitfalls of inguinal herniorrhaphy: surgeon volume matters. Surgery. 2015;158(3):736–746. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AlJamal YN, Zendejas B, Gas BL, Ali SM, Heller SF, Kendrick ML, Farley DR. Annual surgeon volume and patient outcomes following laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repairs. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2016;26(2):92–98. doi: 10.1089/lap.2015.0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stechemesser B, Jacob DA, Schug-Pass C, Köckerling F. Herniamed: an Internet-based registry for outcome research in hernia surgery. Hernia. 2012;16:269–276. doi: 10.1007/s10029-012-0908-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miserez M, Alexandre JH, Campanelli G, Corcione F, Cuccurullo D, Pascual MH, Hoeferlin A, Kingsnorth AN, Mandala V, Palot JP, Schumpelick V, Simmermacher RK, Stoppa R, Flament JB. The European hernia society groin hernia classification: simple and easy to remember. Hernia. 2007;11:113–116. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bökeler U, Schwarz J, Bittner R, Zacheja S, Smaxwil C. Teaching and training in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (TAPP): impact of the learning curve on patient outcome. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(8):2886–2893. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2849-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aquina CT, Kelly KN, Probst CP, Iannuzzi JC, Noyes K, Langstein HN, Monson JRT, Fleming FJ. Surgeon volume plays a significant role in outcomes and cost following open incisional hernia repair. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;2015(19):100–110. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2627-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]