Abstract

The current success of targeted inhibition against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and Programmed Death 1/Programmed Death Ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1, herein collectively referred to as PD) pathways is hailed as a cancer immunotherapy breakthrough. PD-L1, known also as B7 homolog 1 (B7-H1), was initially discovered by Dr. Lieping Chen in 1999. To recognize the seminal contributions by Chen to the development of PD-directed therapy against cancer, the Chinese American Hematologist and Oncologist Network (CAHON) decided to honor him with its inaugural Lifetime Achievement Award in Hematology and Oncology at the CAHON’s 2015 annual meeting. This essay chronicles the important discoveries made by Chen in the exciting field of immuno-oncology, which goes beyond his original fateful finding. It also argues that PD-directed therapy should be appropriately considered as Tumor-Site Immune Modulation Therapy to distinguish it from CTLA-4-based immune checkpoint blocking agents.

Keywords: B7-H1, PD-L1, PD-1, CTLA-4, CD28, immune checkpoint, immunotherapy, immuno-oncology, T cells, tumor-site immune modulation therapy

Background

Monoclonal antibodies targeting the PD pathway have become a critical breakthrough in our long fight against cancer [1, 2]. Distinct from any previous anti-cancer drugs, PD-based cancer therapy neither directly targets tumors, nor simply revamps the immune system non-specifically. It depends on the strategic modulation of a key tumor immune evasive mechanism featured by the PD-L1 (B7-H1) molecule, and controls tumor growth by resetting immune responses in the tumor microenvironment to the homeostatic and beneficial level [3, 4]. Currently, several anti-PD therapeutic agents have been approved for the treatment of multiple cancer types including lung cancer, head and neck cancer, melanoma and others in the United States, Europe, as well as in Japan and other parts of the world. Numerous clinical trials are ongoing worldwide in order to broaden and increase the utility of anti-PD therapeutics to most if not all human cancers, thanks to the impressive clinical efficacy with favorable toxicities of these novel agents. The successful development of PD-modulating medicines has revolutionized the field of immuno-oncology in an unprecedented way, and opens the door for Tumor-Site Immune Modulation Therapy [5] that will profoundly impact basic and clinical immune-oncology research. Indeed, many outstanding reviews have been written on this topic [3–12]. Nevertheless, in this essay, we review the key milestones in the history of anti-PD drug development, and specifically highlight some of Lieping Chen’s contributions to this revolutionary cancer treatment modality.

History of anti-PD drug development and the roles of Lieping Chen

The success of anti-PD drug development benefited from the advancement of our fundamental understanding of both cancer biology and the immune system. Cancer originates from the mutated self of the host in the setting of genotoxic insults with molecular hallmarks of genetic instability and heterogeneity [13, 14]. Most conventional therapies, including radiation, chemotherapy and even molecular-targeted therapies, directly target cancers themselves with improving, but still less desirable efficacy due to significant side-effects, drug resistance and recurrence of more aggressive malignant clones [8, 13, 15]. The limitations of conventional therapies are especially evident for late stage and advanced cancers. In contrast, the immune system, especially the adaptive arm of immunity such as T cells, is capable of surveilling against mutated antigens in tumor cells and controlling tumor growth through specific immune effector mechanisms. Importantly, these immune cells evolve in parallel with tumors, and are capable of sustainable tumor recognition and killing [16, 17]. However, surveillance efficacy often fails due to multiple tumor immune evasive mechanisms, resulting in the outgrowth and metastasis of cancer cells [18, 19]. Efforts in understanding the basic mechanisms of immune tolerance in general and the primary immune evasive mechanisms by cancer cells in particular have been the key to the successful development of drugs targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway.

Many individuals contributed to the success of PD-directed cancer therapy (Table 1 and Fig. 1) [2]. Among them, Lieping Chen’s work is the focus of this review. In the early span of the 1990s, Chen was convinced that in the tumor microenvironment, there exist specific molecular pathways that are primarily responsible for immune evasion, and that this concept could be harnessed for more effective cancer therapy. His passion has been devoted towards the search for these elusive molecules ever since. Trained as a physician-scientist in China, Chen quickly became convinced that basic medical research holds the key to cancer cure. He earned his M.S. degree at the Cancer Institute of Peking Union Medical College in 1986 before obtaining his Ph.D. from Drexel University in 1989. He then undertook his postdoctoral training at the University of Washington, Seattle in 1990, all along focusing on immunology. During that period, important discoveries were made regarding the major immune cell populations with different immune functions, distinguished by cell surface molecules, including CD3, CD4, CD8, T cell receptor (TCR) and others [20–23]. More importantly, the guiding principle of T cell activation and tolerance began to emerge [21]. Among those important events, the discovery of CD28, CTLA-4 and their ligands B7 (B7.1 and B7.2) was the key development in the field [24, 25] which vindicated the two-signal hypothesis for lymphocyte activation proposed by Bretscher and Cohn [26], and extended by Lafferty and his colleagues [27]. The first signal is via TCR triggered by an MHC-antigenic peptide complex, whereas the second signal, also known as a co-stimulation signal, is provided by co-stimulatory molecules expressed on the surface of antigen presenting cells (APC) and T cells (like B7-CD28 pathway). Based on this principle, Chen and his colleagues, for the first time, demonstrated that stably-enforced expression of B7 molecules in cancer cells elicited strong anti-tumor immune responses, leading to eradication of distal tumors [28]. This effect is mainly CD28 dependent: upon ligation of the same B7 ligand, CD28 delivers an essential signal for naïve T cell activation [29], which is in contrast to the CTLA-4 molecule behaving as a T cell “checkpoint” receptor with inhibitory activities [30–33]. Blocking CTLA-4 for immunotherapy of cancer was later steered by James Allison who has played crucial roles in the renaissance of cancer immunology [34–37], whereas Chen’s earlier work laid the groundwork for the therapeutic potential of manipulating co-stimulatory molecules against cancer. However, the ectopic expression of costimulatory molecules like B7 on tumor cells worked effectively against multiple murine tumor models, its application is currently limited in cancer patients [38]. Additionally, since both B7 ligands and CD28/CTLA-4 receptors are expressed broadly without tumor specificity and that they play essential roles in the control of general immune homeostasis, targeting this pathway could be met with severe autoimmune toxicities, which was shown to be the case in the clinical trials of TGN1412, an anti-CD28 super agonist antibody [39], and the anti-CTLA-4 antibodies, ipilimumab and tremelimumab [40–42]. Chen was determined to uncover tumor-specific immune evasion mechanisms and find ways to block them.

Table 1.

Major contributions to the development of targeted cancer immunotherapeutics against CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 Pathways a

| Contributions | CTLA-4 | PD-1 | PD-L1 (B7-H1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Cloning | Pierre Goldstein (1987) [59] | Tasuku Honjo (1992) [57] | Lieping Chen (1999) [47] |

| Inhibitory Function | Jeffery Bluestone (1994) [30] Arlene Sharpe (1995) [32] Tak Mak (1995) [33] |

Tasuku Honjo (1999) [60] |

Lieping Chen (1999) [47] Tasuku Honjo, Clive Wood (2000) [57] b Lieping Chen (2004) [68] |

| Ligand-receptor Interaction | Peter Linsley (1991) [25] | Tasuku Honjo, Clive Wood (2000) [57] b | Tasuku Honjo, Clive Wood (2000) [57] b |

| Function in cancer immunity | James Allison (1996) [34] | NagahiroMinato (2002) [63] Lieping Chen (2005) [70] Tasuku Honjo (2005) [71] |

Lieping Chen (2002) [56] Nagahiro Minato (2002) [63] |

a The discovery of PD-L2 was made by Gordon Freeman and Arlene Sharpe (2001)[61], and Drew Pardoll (2001)[62]. Subsequent work on PD-L2 is not highlighted here

b Gordon Freeman, Andrew Long and Yoshiko Iwai are the three co-first authors of this work, which renamed B7-H1 (its gene cloned one year earlier) to PD-L1

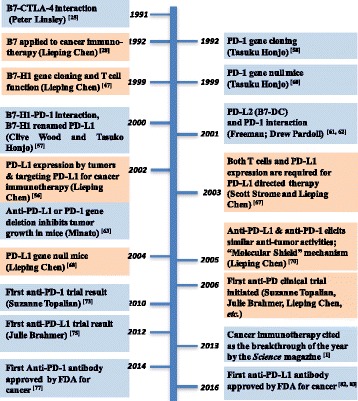

Fig. 1.

Timeline for major events leading to the development of anti-PD drugs. The contributions by Lieping Chen are highlighted in light orange. The contributions by Lieping Chen are highlighted in light orange

During his seven-year tenure at Bristol-Myers Squibb (1990–1997), Lieping Chen evaluated the immune functions and potential anti-tumor effects of many cell surface molecules on T cells, especially 4-1BB (CD137), a molecule specifically expressed by activated T cells and serving as another co-stimulatory receptor. The Chen group were the first to reveal the potent anti-tumor effect of the anti-4-1BB agonistic antibody in both immunogenic and non-immunogenic tumor models [43], making 4-1BB an attractive target for immuno-oncology [44]. Some promising results from the anti-4-1BB clinical trials were recently reported [45]. Although the expression of 4-1BB ligand is relatively broad, 4-1BB expression could accurately identify tumor-reactive T cells [46]. Even so, Chen believed that immune-regulatory molecules with higher tumor specificity remained to be identified. He returned to academia and joined the Mayo Clinic to continue searching for these pathways. Inspired by the progress of the Human Genome Project, Chen turned to informatics to discover candidate molecules from the human expressed sequence tag (EST) libraries based on their predicted homology to B7 family molecules. This effort was incredibly successful; he made several seminal discoveries of a series of novel B7 family members, including B7-H1 (PD-L1) [47], B7-H2 [48], B7-H3 [49], B7-H4 [50], B7-H5 [51], PD-1H (VISTA) [52] and so on [53–55]. In a series of papers, Chen and his colleagues completed the fundamental characterization of the B7-H1’s biological function and provided the very first proof of anti-tumor effects via blockade of B7-H1 [47, 56], which mainly serve as a ligand to PD-1 receptor on T cells [57], a molecule discovered earlier by Tasuku Honjo in Japan [58]. In 2004, Chen joined the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and collaborated with Suzanne Topalian, Julie Brahmer and other clinical investigators to initiate the first clinical trial of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 pathway therapies in patients with cancer. It was this clinical study that opened the floodgate of PD-1/PD-L1 pathway-directed cancer immunotherapy.

The key events that led to the successful development of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drugs are chronicled below (Fig. 1 and Table 1):

From 1990 to 1991, Peter Linsley from the Bristol-Myers Squibb discovered the interaction between CD28, CTLA-4, and B7 [24, 25]. The B7 pathway was later generally considered as an essential co-stimulatory molecule for naïve T cell activation [21, 54].

In 1992, by stably expressing B7 molecule in the tumor cells, Lieping Chen provided the theoretical basis for the therapeutic potential of manipulating the expression of co-stimulatory molecules in the tumor microenvironment for cancer immunotherapy [28, 29].

In 1992, Tasuku Honjo cloned the PD-1 gene (Pdcd1) from immune cell lines undergoing apoptosis [58].

-

In 1994, Jeffery Bluestone first identified the inhibitory function of CTLA-4, and also categorized CTLA-4 as the first cell surface T cell inhibitory receptor [30]*.

*Note: During the process of drug development targeting this molecule, Pierre Goldstein cloned CTLA-4 gene (Ctla4) [59] and Peter Linsley discovered the receptor-ligand interaction between B7 and CTLA-4 [25] (Table 1). Arlene Sharpe and Tak Mak subsequently reported the fatal autoimmune diseases of Ctla4-deficient mice [32, 33]. James Allison characterized the anti-tumor effect of antibody targeting CTLA-4 [34]. The anti-CTLA-4 antibody, ipilimumab, was later approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of melanoma in 2011 [37].

In 1997, Lieping Chen identified the potent anti-tumor effect of agonistic antibody targeting 4-1BB, another co-stimulatory receptor on T cells, which further inspired the field of cancer immunotherapy [43].

Around 1997, given the progress of the Human Genome Project, Lieping Chen’s group started to search for B7-like molecules from the human EST libraries, thus began his seminal works on expanding the members of the B7 family.

In 1999, Chen cloned the first B7 homolog, the human B7-H1 gene, and identified its inhibitory activity on T cells by inducing IL-10 [47]. During the following years, Chen’s group also cloned B7-H2 [48], B7-H3 [49], B7-H4 [50], B7-H5 [51] and PD-1H [52].

In 1999, Tasuku Honjo discovered that the PD-1 gene (Pdcd1) knockout mice have mild autoimmune symptoms, which revealed the inhibitory function of PD-1 in preventing autoimmunity [60].

In 2000, Tasuku Honjo and Clive Wood discovered the interaction between B7-H1 and PD-1, and changed the name of B7-H1 to PD-L1 [57].

In 2001, Arlene Sharpe and Gordon Freeman discovered another PD-1 ligand, PD-L2 (Programmed Death Ligand 2), which also shows inhibitory activity to T cells [61]. Drew Pardoll’s group identified PD-L2 around the same time, and named this molecule B7-DC for its specific expression on dendritic cells [62].

In 2002, Lieping Chen discovered the critical role of B7-H1 (PD-L1) as a potential immune evasion mechanism in the tumor microenvironment. B7-H1 is found to be overexpressed in many human tumor tissues, but minimally detected in the normal tissues, which was mainly regulated by IFN-γ [56]. Most importantly, antibody-targeting B7-H1 could restore T cell function and control tumor growth both in vitro and in vivo [56]. Subsequent works by Nagahiro Minato [63] and Weiping Zou [64] further supported this finding. Moreover, Chen’s study suggested the existence of other receptor(s) for B7-H1, which was later validated by a follow-up mutation study made by Chen [65], and finally led to the discovery of B7-1 as another B7-H1 inhibitory receptor by Arlene Sharpe and Gordon Freeman [66].

In 2003, Scott Strome and Lieping Chen showed that B7-H1 overexpression in tumor cells and T cell activation are two indispensable pre-conditions for the potent anti-cancer effect of antibodies blocking this pathway [67].

In 2004, Lieping Chen discovered that the B7-H1 gene (Cd274) null mice have some spontaneous accumulation of activated CD8+ T cells in the liver, but do not have overt autoimmune manifestations. This work further proved the inhibitory function of B7-H1 and predicted the acceptable safety profile of B7-H1-targeted therapy [68]. An independent study by Arlene Sharpe and Gordon Freeman using Cd274-deficient mice also proved that PD-L1 negatively regulates T cells [69].

In 2004, Lieping Chen joined the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and contributed to the development of the first-in-human trial concept on antibodies targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway for the treatment of advanced cancers.

In 2005, Lieping Chen demonstrated that antibodies blocking either B7-H1 or PD-1 could promote antitumor immune responses, and proposed the “Molecular Shield” mechanism of PD-L1 on tumors that offers resistance to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) [70]. Tasuku Honjo also demonstrated that PD-1 blockade by genetic manipulation or antibody treatment inhibited hematogenous spreading of tumor cells [71].

In 2006, Rafi Ahmed characterized a role of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in T cell exhaustion with the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) chronic infection model [72].

In 2006, the first human cancer clinical trial targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway was launched in the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

In 2010, the first clinical observation on anti-PD-1 treatment was reported by Suzanne Topalian [73].

In 2012, the results of the first two large anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 clinical trials in the Johns Hopkins Hospital, the Yale-New Haven Hospital and others were reported [74, 75].

In 2006, Lieping Chen’s group developed a sensitive and effective immunohistochemistry staining protocol for detecting PD-L1 expression in cancer cells, and pointed out the value of PD-L1 staining in tumor sections on the prediction of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 clinical efficacy in 2012. Chen also refined his theory on anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy by proposing the adaptive resistance concept [76].

In 2013, cancer immunotherapy was selected as the breakthrough of the year by the Science magazine [1, 2].

In 2014, anti-PD-1 antibodies (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) were approved in the United States and Japan for treatment of advanced metastatic melanoma [77], and subsequently for treatment of many other cancer types in 2015–2016 [78–82].

In 2016, the anti-PD-L1 antibody, atezolizumab, was approved by the FDA for the treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma and non-small cell lung cancer [82, 83].

Anti-PD modality and tumor-site immune modulation therapy

The timeline in the history of anti-PD drug development (Fig. 1) spans from the understanding of the B7 pathway in regulating T cell responses to the discovery of the PD pathway with tumor-site immune modulation properties, reflecting our increased understanding of both T cell biology and tumor immunity. This advancement resulted from the progress of research in the field of both immunology and oncology, eventually leading to the birth of immuno-oncology. Ironically, anti-PD antibodies did not show clear anti-tumor effects in many animal models in the early days of research, raising skepticism among many over their therapeutic application. However, Lieping Chen and his colleagues proposed that the potency of anti-PD therapy depends on both the existence of immune cells especially T cells in the tumor site, as well as PD-L1 expression by the tumor cells [67, 70, 84]. He steadfastly and passionately championed the clinical development of agents targeting this pathway. Thus, Chen played key roles in advancing the anti-PD drug program in the areas of basic research as well as in clinical translation (Table 1), for which he was recognized with the 2014 William Coley Award in Basic and Tumor Immunology [85] (shared with Tasuku Honjo, Arlene Sharpe and Gordon Freeman), the 2015 Lifetime Achievement Award in Hematology and Oncology by CAHON (www.cahon.org, and this paper), and the 2016 American Association of Immunologists (AAI)-Steinman Award for Human Immunology Research (http://www.aai.org/Awards/Archive/index.html).

Targeting the PD pathway for treatment of cancer is unique in several aspects, including the following (Figs. 2 and 3):

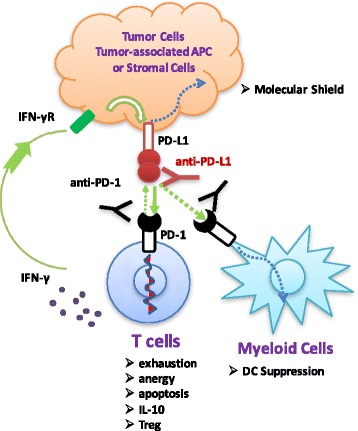

Fig. 2.

Mechanism of the PD pathway in driving tumor-associated immune evasion. Tumor cells, tumor-associated antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and stromal cells upregulate PD-L1 in response to ongoing immune responses, mainly through the action of IFN-γ. The ligation of PD-1 by PD-L1 delivers inhibitory signals to T cells, leading to T cell anergy, functional exhaustion, and apoptosis. PD-1-PD-L1 interaction also favors conversion of T cells to the regulatory T cell (Treg) phenotype with secretion of inhibitory cytokines, such as IL-10. PD-1 on myeloid cells also impairs dendritic cell functions. In addition, PD-L1 reversed signaling on tumor cells can serve as a “Molecular Shield” protecting tumor cells from CTL-mediated killing. IFN-γR: IFN-γ receptor

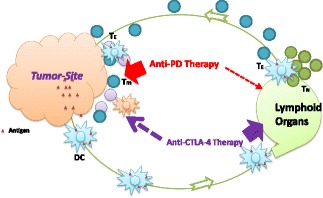

Fig. 3.

Anti-PD modality: Tumor-site immune modulation therapy. Anti-PD therapy is mechanistically distinct from anti-CTLA-4 therapy: the latter affects immune responses more systemically, whereas anti-PD therapy primarily targets its actions at the tumor site. Anti-PD modality is thus capable of repairing tumor-induced immune defects, ultimately leading to resetting of the anti-tumor immunity to a desirable level. TN: Naïve T cells; TE: T effector cells; Tm: memory T cells; DC: dendritic cells

First, the action of anti-PD therapy is primarily localized to the tumor site. The ligand for PD-1, PD-L1 (B7-H1), has high expression on tumor cells. It is absent in the majority of normal tissues, but could be induced in the tumor microenvironment by ongoing immune responses, mostly by the cytokine IFN-γ [3, 56]. This tumor-localized effect of PD-L1 dictates that the antibodies targeting either ligand or receptor will work in the tumor microenvironment with ongoing immune responses. In contrast, PD-L2, another ligand of PD-1, has weak expression in tumors and is constitutively expressed by dendritic cells [53, 54]. The expression pattern of PD-L2 likely explains why targeting PD-L2 has only minor anti-tumor effects, although PD-L2 and PD-L1 have similar binding affinity to PD-1, and their inhibitory effects on T cells in vitro are comparable.

Second, targeting the PD pathway repairs or resets tumor-associated immune defects. The PD-L1 molecule is a key mechanism for tumor-mediated immune evasion [3]. The ligation of PD-L1 to PD-1 causes functional defects in T cells through several different mechanisms (Fig. 2), including anergy to antigen stimulation [86–88], functional exhaustion [72], apoptosis [56], induction of immune suppressor cells [89, 90], and secretion of inhibitory cytokines, such as IL-10 [47]. PD-1 on myeloid cells also impairs dendritic cell functions [91]. In addition, PD-L1 reverse-signaling on tumor cells was found to serve as a “Molecular Shield,” protecting the tumor from killing by CTLs [70, 92]. Importantly, this type of immune defect is not permanent, and can be restored by termination of this pathway, especially by the antibody blockade of either PD-L1 or PD-1 [70]. Moreover, anti-PD therapy may reset the global anti-tumor immune defects possibly by yet unknown “cascade reaction” mechanisms, as profound and sustainable therapeutic effects have been observed in many patients receiving this therapy [3].

Third, the PD blockade aims to normalize the anti-tumor immune response but not over-exuberate immune responses in general. Blockade of either PD-L1 or PD-1 is not to simply amplify immunity, but to re-adjust the anti-tumor immune responses to a desirable level (Fig. 3). Given the mild and rare autoimmune symptoms observed in PD-L1 and PD-1 gene-deficient mice [60, 68] and weak expression of these molecules by normal tissues [56, 93], targeting the PD pathway in the tumor settings will normalize anti-tumor immunity but spare the normal peripheral tolerance mechanism against self-antigens [3]. Thus, anti-PD treatment has an understandably great safety window [94].

These abovementioned features of the PD pathway are very unique among the many pathways currently tested for cancer immunotherapy. Strictly speaking, PD-1/PD-L1 is the only known pathway responsible for key tumor-specific immune evasion mechanisms so far. Yet, both PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 are often lumped together as “immune checkpoints” [6, 8, 31, 95], which is an immunological term defining a plethora of inhibitory pathways in the control of physiological immune responses [6]. This concept does not distinguish the immune modulating role of anti-PD therapy from the actions of anti-CTLA-4 therapy [3, 7] (Fig. 3). An alternative term of “Tumor-Site Immune Modulation Therapy” might better describe the attributes of anti-PD therapy [5], which is characterized by targeting molecules responsible for tumor-site specific immune evasion mechanisms, resetting and restoring the anti-tumor immunity back to a desirable level. Such action is clearly different from CTLA-4 blockade, which overdrives systemic T cell immunity including self-reactive T cell responses.

Lieping Chen continues his journey to discover more PD-like molecules, aiming to convert human cancers to chronic and manageable diseases via exploiting the power of the hardwired immune system. His contributions to this field have cemented his place in immuno-oncology.

Acknowledgements

We thank many members of CAHON for stimulating discussions on the topic.

Funding

Z.L. is supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health grants DK105033, CA186866, CA188419 and AI070603.

Availability of data and materials

The material supporting the conclusion of this review has been included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

All authors discussed the topic, contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

This is not applicable to this review.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is not applicable to this review.

Contributor Information

Delong Liu, Email: delong_liu@nymc.edu.

Zihai Li, Email: zihai@musc.edu.

References

- 1.Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer Immunother Sci. 2013;342(6165):1432–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.342.6165.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pardoll D. Immunotherapy: it takes a village. Science. 2014;344(6180):149. doi: 10.1126/science.344.6180.149-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L, Han X. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy of human cancer: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(9):3384–3391. doi: 10.1172/JCI80011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: Mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(328):328rv324. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen L. From the guest editor: Tumor site immune modulation therapy. Cancer J. 2014;20(4):254–255. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okazaki T, Chikuma S, Iwai Y, Fagarasan S, Honjo T. A rheostat for immune responses: the unique properties of PD-1 and their advantages for clinical application. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(12):1212–1218. doi: 10.1038/ni.2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma P, Allison JP. Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell. 2015;161(2):205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lesokhin AM, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Wolchok JD. On being less tolerant: enhanced cancer immunosurveillance enabled by targeting checkpoints and agonists of T cell activation. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(280):280sr281. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boussiotis VA. Molecular and Biochemical Aspects of the PD-1 Checkpoint Pathway. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1767–1778. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1514296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Immune checkpoint blockade: a common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(4):450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339(6127):1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiao J, Liu Z, Fu YX. Adapting conventional cancer treatment for immunotherapy. J Mol Med (Berl) 2016;94(5):489–495. doi: 10.1007/s00109-016-1393-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gajewski TF, Schreiber H, Fu YX. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(10):1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/ni.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331(6024):1565–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swann JB, Smyth MJ. Immune surveillance of tumors. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(5):1137–1146. doi: 10.1172/JCI31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mittal D, Gubin MM, Schreiber RD, Smyth MJ. New insights into cancer immunoediting and its three component phases--elimination, equilibrium and escape. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;27:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reinherz EL. Revisiting the Discovery of the alphabeta TCR Complex and Its Co-Receptors. Front Immunol. 2014;5:583. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz RH. Historical overview of immunological tolerance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(4):a006908. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisen HN, Schlesinger S. Remembrance of immunology past: conversations with Herman Eisen. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-111214-122349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mak TW. The T cell antigen receptor: “The Hunting of the Snark”. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(Suppl 1):S83–93. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linsley PS, Clark EA, Ledbetter JA. T-cell antigen CD28 mediates adhesion with B cells by interacting with activation antigen B7/BB-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(13):5031–5035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linsley PS, Brady W, Urnes M, Grosmaire LS, Damle NK, Ledbetter JA. CTLA-4 is a second receptor for the B cell activation antigen B7. J Exp Med. 1991;174(3):561–569. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bretscher P, Cohn M. A theory of self-nonself discrimination. Science. 1970;169(950):1042–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3950.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lafferty KJ, Prowse SJ, Simeonovic CJ, Warren HS. Immunobiology of tissue transplantation: a return to the passenger leukocyte concept. Annu Rev Immunol. 1983;1:143–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.01.040183.001043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen L, Ashe S, Brady WA, Hellstrom I, Hellstrom KE, Ledbetter JA, McGowan P, Linsley PS. Costimulation of antitumor immunity by the B7 counterreceptor for the T lymphocyte molecules CD28 and CTLA-4. Cell. 1992;71(7):1093–1102. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen L, Linsley PS, Hellstrom KE. Costimulation of T cells for tumor immunity. Immunol Today. 1993;14(10):483–486. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90262-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walunas TL, Lenschow DJ, Bakker CY, Linsley PS, Freeman GJ, Green JM, Thompson CB, Bluestone JA. CTLA-4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activation. Immunity. 1994;1(5):405–413. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90071-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korman AJ, Peggs KS, Allison JP. Checkpoint blockade in cancer immunotherapy. Adv Immunol. 2006;90:297–339. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)90008-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tivol EA, Borriello F, Schweitzer AN, Lynch WP, Bluestone JA, Sharpe AH. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity. 1995;3(5):541–547. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waterhouse P, Penninger JM, Timms E, Wakeham A, Shahinian A, Lee KP, Thompson CB, Griesser H, Mak TW. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla-4. Science. 1995;270(5238):985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science. 1996;271(5256):1734–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, O’Day S, Weber J, Garbe C, Lebbe C, Baurain JF, Testori A, Grob JJ, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N England J Med. 2011;364(26):2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cameron F, Whiteside G, Perry C. Ipilimumab: first global approval. Drugs. 2011;71(8):1093–1104. doi: 10.2165/11594010-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh P, Pal SK, Alex A, Agarwal N. Development of PROSTVAC immunotherapy in prostate cancer. Future Oncol. 2015;11(15):2137–2148. doi: 10.2217/fon.15.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suntharalingam G, Perry MR, Ward S, Brett SJ, Castello-Cortes A, Brunner MD, Panoskaltsis N. Cytokine storm in a phase 1 trial of the anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody TGN1412. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(10):1018–1028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fecher LA, Agarwala SS, Hodi FS, Weber JS. Ipilimumab and its toxicities: a multidisciplinary approach. Oncologist. 2013;18(6):733–743. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ribas A, Kefford R, Marshall MA, Punt CJ, Haanen JB, Marmol M, Garbe C, Gogas H, Schachter J, Linette G, et al. Phase III randomized clinical trial comparing tremelimumab with standard-of-care chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(5):616–622. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ibrahim RA, Berman DM, DePril V, Humphrey RW, Chen T, Messina M, Chin KM, Liu HY, Bielefield M, Hoos A. Ipilimumab safety profile: Summary of findings from completed trials in advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(15_suppl):8583. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melero I, Shuford WW, Newby SA, Aruffo A, Ledbetter JA, Hellstrom KE, Mittler RS, Chen L. Monoclonal antibodies against the 4-1BB T-cell activation molecule eradicate established tumors. Nat Med. 1997;3(6):682–685. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanmamed MF, Pastor F, Rodriguez A, Perez-Gracia JL, Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Jure-Kunkel M, Melero I. Agonists of Co-stimulation in Cancer Immunotherapy Directed Against CD137, OX40, GITR, CD27, CD28, and ICOS. Semin Oncol. 2015;42(4):640–655. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chester C, Ambulkar S, Kohrt HE. 4-1BB agonism: adding the accelerator to cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65(10):1243–1248. doi: 10.1007/s00262-016-1829-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye Q, Song DG, Poussin M, Yamamoto T, Best A, Li C, Coukos G, Powell DJ., Jr CD137 accurately identifies and enriches for naturally occurring tumor-reactive T cells in tumor. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(1):44–55. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dong H, Zhu G, Tamada K, Chen L. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nat Med. 1999;5(12):1365–1369. doi: 10.1038/70932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang S, Zhu G, Chapoval AI, Dong H, Tamada K, Ni J, Chen L. Costimulation of T cells by B7-H2, a B7-like molecule that binds ICOS. Blood. 2000;96(8):2808–2813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chapoval AI, Ni J, Lau JS, Wilcox RA, Flies DB, Liu D, Dong H, Sica GL, Zhu G, Tamada K, et al. B7-H3: a costimulatory molecule for T cell activation and IFN-gamma production. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(3):269–274. doi: 10.1038/85339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sica GL, Choi IH, Zhu G, Tamada K, Wang SD, Tamura H, Chapoval AI, Flies DB, Bajorath J, Chen L. B7-H4, a molecule of the B7 family, negatively regulates T cell immunity. Immunity. 2003;18(6):849–861. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu Y, Yao S, Iliopoulou BP, Han X, Augustine MM, Xu H, Phennicie RT, Flies SJ, Broadwater M, Ruff W, et al. B7-H5 costimulates human T cells via CD28H. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2043. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flies DB, Wang S, Xu H, Chen L. Cutting edge: A monoclonal antibody specific for the programmed death-1 homolog prevents graft-versus-host disease in mouse models. J Immunol. 2011;187(4):1537–1541. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen L. Co-inhibitory molecules of the B7-CD28 family in the control of T-cell immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(5):336–347. doi: 10.1038/nri1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen L, Flies DB. Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(4):227–242. doi: 10.1038/nri3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schildberg FA, Klein SR, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. Coinhibitory Pathways in the B7-CD28 Ligand-Receptor Family. Immunity. 2016;44(5):955–972. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, Roche PC, Lu J, Zhu G, Tamada K, et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8(8):793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, Bourque K, Chernova T, Nishimura H, Fitz LJ, Malenkovich N, Okazaki T, Byrne MC, et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med. 2000;192(7):1027–1034. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, Honjo T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992;11(11):3887–3895. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brunet JF, Denizot F, Luciani MF, Roux-Dosseto M, Suzan M, Mattei MG, Golstein P. A new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily--CTLA-4. Nature. 1987;328(6127):267–270. doi: 10.1038/328267a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nishimura H, Nose M, Hiai H, Minato N, Honjo T. Development of lupus-like autoimmune diseases by disruption of the PD-1 gene encoding an ITIM motif-carrying immunoreceptor. Immunity. 1999;11(2):141–151. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Latchman Y, Wood CR, Chernova T, Chaudhary D, Borde M, Chernova I, Iwai Y, Long AJ, Brown JA, Nunes R, et al. PD-L2 is a second ligand for PD-1 and inhibits T cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(3):261–268. doi: 10.1038/85330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tseng SY, Otsuji M, Gorski K, Huang X, Slansky JE, Pai SI, Shalabi A, Shin T, Pardoll DM, Tsuchiya H. B7-DC, a new dendritic cell molecule with potent costimulatory properties for T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;193(7):839–846. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.7.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iwai Y, Ishida M, Tanaka Y, Okazaki T, Honjo T, Minato N. Involvement of PD-L1 on tumor cells in the escape from host immune system and tumor immunotherapy by PD-L1 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(19):12293–12297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192461099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Curiel TJ, Wei S, Dong H, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, Krzysiek R, Knutson KL, Daniel B, Zimmermann MC, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 improves myeloid dendritic cell-mediated antitumor immunity. Nat Med. 2003;9(5):562–567. doi: 10.1038/nm863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang S, Bajorath J, Flies DB, Dong H, Honjo T, Chen L. Molecular modeling and functional mapping of B7-H1 and B7-DC uncouple costimulatory function from PD-1 interaction. J Exp Med. 2003;197(9):1083–1091. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Butte MJ, Keir ME, Phamduy TB, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. Programmed death-1 ligand 1 interacts specifically with the B7-1 costimulatory molecule to inhibit T cell responses. Immunity. 2007;27(1):111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Strome SE, Dong H, Tamura H, Voss SG, Flies DB, Tamada K, Salomao D, Cheville J, Hirano F, Lin W, et al. B7-H1 blockade augments adoptive T-cell immunotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63(19):6501–6505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dong H, Zhu G, Tamada K, Flies DB, van Deursen JM, Chen L. B7-H1 determines accumulation and deletion of intrahepatic CD8(+) T lymphocytes. Immunity. 2004;20(3):327–336. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(04)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Latchman YE, Liang SC, Wu Y, Chernova T, Sobel RA, Klemm M, Kuchroo VK, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-L1-deficient mice show that PD-L1 on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and host tissues negatively regulates T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(29):10691–10696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307252101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hirano F, Kaneko K, Tamura H, Dong H, Wang S, Ichikawa M, Rietz C, Flies DB, Lau JS, Zhu G, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 and PD-1 by monoclonal antibodies potentiates cancer therapeutic immunity. Cancer Res. 2005;65(3):1089–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iwai Y, Terawaki S, Honjo T. PD-1 blockade inhibits hematogenous spread of poorly immunogenic tumor cells by enhanced recruitment of effector T cells. Int Immunol. 2005;17(2):133–144. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, Zhu B, Allison JP, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ, Ahmed R. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature. 2006;439(7077):682–687. doi: 10.1038/nature04444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, Powderly JD, Picus J, Sharfman WH, Stankevich E, Pons A, Salay TM, McMiller TL, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3167–3175. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Taube JM, Anders RA, Young GD, Xu H, Sharma R, McMiller TL, Chen S, Klein AP, Pardoll DM, Topalian SL, et al. Colocalization of inflammatory response with B7-h1 expression in human melanocytic lesions supports an adaptive resistance mechanism of immune escape. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(127):127ra137. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Poole RM. Pembrolizumab: first global approval. Drugs. 2014;74(16):1973–1981. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0314-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sul J, Blumenthal GM, Jiang X, He K, Keegan P, Pazdur R. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Patients With Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Whose Tumors Express Programmed Death-Ligand 1. Oncologist. 2016;21(5):643–650. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kazandjian D, Suzman DL, Blumenthal G, Mushti S, He K, Libeg M, Keegan P, Pazdur R. FDA Approval Summary: Nivolumab for the Treatment of Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer With Progression On or After Platinum-Based Chemotherapy. Oncologist. 2016;21(5):634–642. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Raedler LA. Opdivo (Nivolumab): Second PD-1 Inhibitor Receives FDA Approval for Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(Spec Feature):180–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goodman A, Patel SP, Kurzrock R. PD-1-PD-L1 immune-checkpoint blockade in B-cell lymphomas. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.168. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 82.Nods for Atezolizumab and Nivolumab from FDA. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(8):811. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 83.Markham A. Atezolizumab: First Global Approval. Drugs. 2016;76(12):1227–1232. doi: 10.1007/s40265-016-0618-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sznol M, Chen L. Antagonist antibodies to PD-1 and B7-H1 (PD-L1) in the treatment of advanced human cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(5):1021–1034. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tontonoz M, Gee CE. Cancer immunotherapy out of the gate: the 22nd annual Cancer Research Institute International Immunotherapy Symposium. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3(5):444–448. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Selenko-Gebauer N, Majdic O, Szekeres A, Hofler G, Guthann E, Korthauer U, Zlabinger G, Steinberger P, Pickl WF, Stockinger H, et al. B7-H1 (programmed death-1 ligand) on dendritic cells is involved in the induction and maintenance of T cell anergy. J Immunol. 2003;170(7):3637–3644. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tsushima F, Yao S, Shin T, Flies A, Flies S, Xu H, Tamada K, Pardoll DM, Chen L. Interaction between B7-H1 and PD-1 determines initiation and reversal of T-cell anergy. Blood. 2007;110(1):180–185. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-060087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Goldberg MV, Maris CH, Hipkiss EL, Flies AS, Zhen L, Tuder RM, Grosso JF, Harris TJ, Getnet D, Whartenby KA, et al. Role of PD-1 and its ligand, B7-H1, in early fate decisions of CD8 T cells. Blood. 2007;110(1):186–192. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-062422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Francisco LM, Salinas VH, Brown KE, Vanguri VK, Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK, Sharpe AH. PD-L1 regulates the development, maintenance, and function of induced regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206(13):3015–3029. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Amarnath S, Mangus CW, Wang JC, Wei F, He A, Kapoor V, Foley JE, Massey PR, Felizardo TC, Riley JL, et al. The PDL1-PD1 axis converts human TH1 cells into regulatory T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(111):111ra120. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yao S, Wang S, Zhu Y, Luo L, Zhu G, Flies S, Xu H, Ruff W, Broadwater M, Choi IH, et al. PD-1 on dendritic cells impedes innate immunity against bacterial infection. Blood. 2009;113(23):5811–5818. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Azuma T, Yao S, Zhu G, Flies AS, Flies SJ, Chen L. B7-H1 is a ubiquitous antiapoptotic receptor on cancer cells. Blood. 2008;111(7):3635–3643. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-123141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Petroff MG, Chen L, Phillips TA, Hunt JS. B7 family molecules: novel immunomodulators at the maternal-fetal interface. Placenta. 2002;23(Suppl A):S95–101. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, Connell LC, Schindler K, Lacouture ME, Postow MA, Wolchok JD. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(12):2375–2391. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015;348(6230):56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The material supporting the conclusion of this review has been included within the article.