Abstract

This study examined the role of maintaining relational harmony among family members in the use of drug refusal strategies for rural Hawaiian youth. Youth focus groups were conducted to validate refusal strategies used in realistic, hypothetical drug-related problem situations. The findings suggested gender-specific motivations for maintaining relational harmony among family members when faced with drug offers from them. Specifically, boys described instrumental concerns when using refusal strategies (i.e., not wanting to get into trouble), while girls described holistic relational concerns (i.e., not wanting family members to be upset with each other). Implications for prevention and social work practice are discussed.

Keywords: Native Hawaiian, youth, drugs, culturally grounded prevention, family

In recent years, there has been significant attention related to the development of culturally relevant interventions for indigenous populations and communities (Tribal Evaluation Workgroup, 2013; Okamoto, Kulis, Marsiglia, Holleran Steiker, & Dustman, 2014). These interventions reflect researcher-community partnerships to develop programs that match the norms, values, and worldviews of specific indigenous groups. The goal of these developmental efforts is to create programs that balance program efficacy with community feasibility and acceptability, thereby promoting the overall utility and sustainability of these programs (Okamoto et al., 2014). As a first step toward the development of these programs, pre-prevention research with a specific indigenous group can help to identify core norms and values, which can serve as the foundation for the development of culturally relevant programs.

As part of a federally funded, pre-prevention study focused on Native Hawaiian youth and drug use, the present study examined the goal of maintaining relational harmony for rural Hawaiian youth when refusing drug offers from family members. Specifically, this study used focus groups to examine how maintaining relational harmony among family members affects the types of strategies used by rural Hawaiian youth to resist offers to use drugs and/or alcohol. This study explores how Native Hawaiian youth balance drug offer refusal strategies with maintaining relational harmony with family members, and how the selection of these strategies varies by gender. The findings from this study have implications for developing culturally relevant interventions for rural, indigenous, and Pacific Islander youth populations.

Literature Review

While there have been many published adolescent substance abuse intervention studies spanning over several decades (Tobler & Stratton, 1997), intervention studies on indigenous youth are lacking (Beauvais, & Trimble, 2003; Edwards, Giroux, & Okamoto, 2010; Hawkins, Cummins, & Marlatt, 2008; Mokuau, Garlock-Tuiali‘i, & Lee, 2008). Studies that have been conducted with indigenous youth samples have primarily been epidemiological in nature, and have shown that they experience higher rates of substance abuse than majority populations. For example, Okamoto, Kulis, Helm, Edwards, and Giroux (2014) found that Native Hawaiian youth had a significantly higher risk for substance abuse than non-Native Hawaiian youth, while Dunne, Yeo, Keane, and Elkins (2000) found that indigenous Australian adolescents ages 13 to 17 were more likely to abuse substances than non-indigenous youth.

Thus, it is important that relevant prevention methods are used in order to reduce substance abuse for indigenous adolescents. In this vein, culturally-grounded interventions are particularly important, because they balance community input in the development and implementation of interventions with overall program effectiveness (Okamoto et al., 2014). However, in part due to the cost and time to develop these interventions, the relative number of these types of programs are lacking (Lauricella, Valdez, Okamoto, Helm, & Zaremba, 2016). In order to create effective, culturally grounded drug prevention programs for indigenous youth, cultural norms and values that can influence substance use in indigenous youth must be meaningfully integrated into these programs. Two such norms in indigenous cultures are the importance of familial relationships and maintaining harmony within those relationships.

Familial Relationships and Harmony

Familial interconnectedness and relationships are highly valued in indigenous cultures (Hurdle, Okamoto, & Miles, 2003; Okamoto, Helm, Po‘a-Kekuawela, Nebre, & Chin, 2009). For example, in Native Hawaiian culture, family is greatly valued through the ‘ohana system (McCubbin & Marsella, 2009; Mokuau, 2011). Past research has found that Native Hawaiians interact with family members more frequently than other major ethnic groups (Goebert et al., 2000). Since family plays a central role in the Native Hawaiian culture, it would follow that maintaining harmony within familial relationships would be an important consideration in substance abuse prevention for Native Hawaiian youth.

More broadly, maintaining relational harmony in the family has been shown to influence substance abuse in adolescents. Defined as the ability to avoid conflict, Schafer (2011) found that families with disrupted harmony displayed significantly higher rates of adolescent substance abuse. Schafer’s study suggested that in order to maintain relational harmony within the family, youth were pressured to accept offers for substances from their family members. Studies have further shown that familial drug offers can be particularly problematic for indigenous youth and their families. For example, Heavyrunner-Rioux and Hollist (2010) suggested that Native American youth are often influenced by their families to try illegal substances, while Okamoto, Kulis, Helm, Edwards, and Giroux (2014) found that family drug offers and contexts were highly predictive of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use for rural Native Hawaiian youth. While the relationship between adolescent substance abuse and family drug offers has been identified in past research, the role of maintaining relational harmony within drug-related problem situations of indigenous youth has not been closely examined. Specifically, youths’ consideration for their relationships between family members and themselves, and how drug refusal might negatively impact those relationships, has not been explored as a factor which may influence their decisions to accept substances from family members.

Relevance of the Study

The focus of this study is on an under-researched indigenous population with significant health-related needs (Okamoto, 2011). Similar to other indigenous populations in the continental U.S. and the Pacific region, Native Hawaiians have disproportionately suffered from health disparities, including substance abuse. Also similar to other indigenous populations, these disparities have been linked to historical and ecological trauma resulting from forced religious, geopolitical, and socioeconomic colonization (Helm et al., 2015). For example, Silva (2005) used historical Hawaiian records to describe how the stress from being forced to discard one’s culture, beliefs, customs, and traditions can lead to self-destructive coping mechanisms, such as drug and alcohol addictions, for Native peoples. Geographically, the highest proportions of Hawaiians reside in rural areas in the State of Hawai‘i, which are concentrated on islands other than O‘ahu. The focus of this study is on Hawai‘i Island, which has second highest percentage of Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders among all islands in the State (12.7%; U.S. Census Bureau, 2014).

The present study examines the role of maintaining relational harmony among family members in the use of drug resistance strategies of rural Native Hawaiian youth. Recent pilot/feasibility drug prevention research focused on rural Hawaiian youth suggests that maintaining relational harmony among family members may play an important role in the types of strategies used within drug-related problem situations. Okamoto, Kulis, Helm, Lauricella, and Valdez (2016) evaluated the Ho‘ouna Pono curriculum, which is a school-based, drug prevention curriculum that includes videos depicting offers to use substances by peers and family members. The pilot evaluation of the curriculum had shown a significant effect on improving interpersonal relationships, demonstrated through ameliorating fighting behavior for youth exposed to the intervention at 6- and 12-month follow up (Okamoto et al., 2016; Okamoto & Helm, 2015). These findings were particularly pronounced for girls in the sample. Growth curve modeling across four waves of data (i.e., pre-test, post-test, 6-month, and 12-month follow up) illustrated significant decreases in fighting for girls in the intervention group (Okamoto & Helm, 2015). The curriculum also was effective in sustaining the use of non-confrontational drug resistance strategies (avoiding the situation where drugs were being offered, explaining why the youth did not want to use drugs, and/or leaving the situation where drugs were being offered) for intervention youth at 6- and 12-month follow up. Growth curve modeling further illustrated significant increases in the use of selected non-confrontational resistance skills (i.e., avoiding the situation where drugs were being offered) for girls in the intervention group (Okamoto & Helm, 2015). Combined, these findings suggest that the use of non-confrontational drug resistance strategies used by youth in the intervention group may have mitigated interpersonal conflict, as demonstrated through a significant reduction in fighting in the intervention group.

The present study uses qualitative data and analyses to examine the role that maintaining relational harmony among family members may have on the selection and use of specific drug refusal strategies of rural Hawaiian youth. This study expands upon Okamoto et al.’s (2016) and Okamoto and Helm’s (2015) quantitative findings by qualitatively analyzing the influence of relational harmony on drug resistance strategies within Native Hawaiian families. In order to effectively deal with drug-related problem situations involving family members, Hawaiian youth need to be able to balance instrumental goals (i.e., drug refusal) with relational goals (i.e., maintaining family harmony). The present study examines how these goals are balanced for rural Hawaiian youth based on gender. Ultimately, these findings can help to inform future drug prevention efforts for Hawaiian youth, and has implications for prevention efforts with other indigenous youth populations.

Method

Data from this study came from a multi-year pilot/feasibility drug prevention study funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, in which youth participants were asked to adapt and/or validate narrative scripts to be used to create culturally grounded drug prevention videos. All research procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Hawai‘i Pacific University, the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, and the State of Hawai‘i Department of Education.

Sampling and Participants

Six middle or intermediate schools and two high schools within two of the three public school complex areas on Hawai‘i Island participated in this study. Participating schools were located in low-income, rural communities. Several of these communities were geographically isolated, had populations less than 50,000, and had a higher percentage of youth in schools who received free or reduced cost school lunches (Mschool = 68.8, SD = 12.3, Range = 51.9–83.7) compared to the State (49.9; Accountability Resource Center Hawai‘i, 2012). Participant recruitment for the study was conducted in collaboration with school-based research liaisons. These liaisons were typically school staff members, such as teachers or school counselors, who had long-standing professional relationships with the university-based research team from a prior multi-year, pre-prevention study. The liaisons assisted in the recruitment of Hawaiian students, and responded to student and parent questions about the study. They also assisted in the distribution and collection of parental consent forms from the students, and secured space within their respective schools for the focus group discussions.

Seventy-four youth participated in the study. Sixty percent of the youth participants were female, and their mean age was 13.21 years (SD = 2.17). The mean number of youth participating per school was 9.25 (SD = 2.76). The majority of these youth were in the 7th grade (38%), followed by the 8th grade (22%), 12th grade (18%), 6th grade (11%), 11th grade (7%), and the 9th and 10th grades (1% each). In terms of ethnicity, approximately 88% of the youth indicated they were Hawaiian or part-Hawaiian; however, the majority of these youth also identified with additional ethnocultural groups, such as Chinese (42%), Filipino (54%), Portuguese (49%), and White (41%). Of the youth that indicated they were Hawaiian or part-Hawaiian, 80 percent of them indicated that they primarily identified with their Hawaiian background over their other ethnic backgrounds.

Procedures

Youth participated in one of 15 gender-specific focus groups (2–10 youth per group; M = 4.63, SD = 2.33), and the gender of the group facilitators matched that of the youth participants. The goal of each group was to adapt and/or validate one of seven different narrative scripts to be used to film realistic, culturally grounded drug prevention videos focused on rural Hawaiian youth. Each script outlined a brief vignette based upon a drug-related problem situation developed and validated from prior research (Okamoto, Helm, Giroux, Edwards, & Kulis, 2010). Table 1 outlines the script names, associated drug-related problem situations, and the gender composition of the groups that adapted and/or validated each script. Following each scripted situation, three different types of responses for drug refusal were outlined, such as avoiding the situation or saying “no.” Refusal strategies corresponding to each scripted situation also had been developed and validated in prior research (Okamoto, Helm, Giroux, Kaliades, et al., 2010; Okamoto, Helm, Giroux, & Kaliades, 2011). The semi-structured interview schedule used for the focus groups is presented in Table 2. Participants were informed to keep all youth disclosures in the group setting confidential. Because we audio recorded the interviews, youth were asked to use pre-selected pseudonyms to refer to one’s self and others participating in the group discussions, as well as to use pseudonyms to refer to individuals in their stories.

Table 1.

Narrative Script Names, Drug-Related Problem Situations, and Group Gender

| Script Name | Situation | Group Gender |

|---|---|---|

| Bacardi Party | Your friends bring Bacardi to school and mix it with juice. They are drinking it on campus during recess. They offer you some. | Female |

| Bully Boy | A big, bulky boy in school is known to be the leader of a group of “tough kids,” who fight and do drugs. He approaches you one day at recess and asks you if you'd like to hang out with his group. | Male |

| Kanikapila Invite | On the nights that there is a full moon lots of the older kids like to go out at night because they can kanikapila (play music) and smoke marijuana and drink beer outside. Your older cousin invites you to come along. | Male |

| Oh Brother | Your older brother enters your bedroom, closes the door, and asks you if you’d like to smoke some weed. | Male |

| One Time | You are with a girl/boy you like and some other friends. They are all hiding in the bushes and smoking weed. They ask you if you want to try some. After you say no, they say, “Just try this once, it's cool.” | Female |

| Pā ‘ina | You are at a family party (pā‘ina) where the adults have coolers full of beer. They are getting drunk, so you and your cousins can take a beer without the adults noticing. One of your cousins says to you, “Let's grab one.” | Female |

| Pulehu | Your dad, uncles, papa, and dad’s friends are making pulehu (barbeque) in the yard, and you are with them. Your mom is inside the house. They are drinking a lot of beer, probably already drunk. Your dad offers you a beer. | Male and Female |

Table 2. Semi-Structured Interview Schedule.

Pre-Focus Group Description for Youth Participants. The purpose of this group discussion is for you to react to a generic script focused on a drug related situation developed by middle school aged youth on the Big Island, in order to change the content and language of the script to reflect how kids in your community would act or talk in this situation. Your feedback is very important, because we want to make sure that the scripts are realistic for youth who live in your community. We will be using your feedback to modify the script, which will then be used as the main dialogue in a filmed vignette related to drug or alcohol use.

| Semi-Structured Interview Schedule |

|---|

|

Data Analysis

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a member of the research team. As an added layer of research protection, participants’ self-selected pseudonyms were replaced by a researcher-selected pseudonym in the analyzed transcript and disseminated results. To ensure data quality, each transcript was reviewed for accuracy by at least two different research team members. The data analysis strategy followed the principles of grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). A comprehensive set of open codes was identified by the Principal and Co-Principal Investigators, and was imported into a qualitative research data analysis program (NVivo; Richards, 2005). NVivo is one of several code-based theory-building programs that allow the researcher to represent relationships among codes or build higher-order classifications (Weitzman, 2000). In order to establish intercoder reliability and validity, all members of the research team collectively coded one transcript, in order to clarify the definition and parameters of each of the codes. Then, all subsequent transcripts were separately coded and cross-checked by at least two different research team members. Narrative segments that were not identically coded by the team members were identified, discussed, and justified for inclusion or exclusion in the data set. As an additional validation check, after all transcripts were coded and entered into NVivo, the content of conceptually complex codes was again reviewed and validated by the research team. This allowed for further clarification and verification of the code content. Upon establishing intercoder reliability and validity, an analysis of the changes to the narrative scripts suggested by the youth participants was conducted. Gender differences were systematically examined within each of the codes, including differences in content and the manner in which male and female youth participants discussed the drug-related problem situations and their associated responses depicted in each of the scripts.

Results

Six of the fifteen focus groups (three boys’ groups and three girls’ groups) discussed the importance of relational harmony within drug-related problem situations. The mean percentage of coverage within groups referencing the Harmony code was 16.671, with 19.99 among girls’ groups and 13.35 among boys’ groups. Discussions related to four of the scripts addressed the topic of relational harmony among family members. These scripts were “Kanikapila Invite” (boys), “Pā‘ina” (girls), “Oh Brother” (boys) and “Pulehu” (boys and girls; see Table 1).

Boys’ Relational Considerations in Drug Resistance

In the discussion of scripts within boys’ groups, participants expressed concerns about maintaining harmony between the youth protagonist in the script and various family members, but did not appear to be as concerned about maintaining relational harmony between other family members. In other words, the boys appeared to have more instrumental motives focused on themselves (i.e., not getting in trouble with other family members), but were not necessarily concerned whether the family members were mad at each other. For example, in the Pulehu script, the boys expressed concern with how the protagonist (Ku‘u) should tell the mother character about the various drug offers from their family members. The boys knew that the mother character would be mad, so they suggested Ku‘u would want to tell her in a way that other family members would not know that she had told her. This was intended to preserve the relationship between Ku‘u and other family members in the script, but at the expense of jeopardizing the relationship among the family members. In the following quote, the group endorsed behaviors which could be used to distract Ku‘u’s intoxicated father and uncles so that she could leave the situation and secretly tell her mother what was happening to her, rather than overtly calling attention to her father's behavior.

Facilitator: Well, but before that though. Before that, right? Umm, Kana [Ku‘u’s father] says, “Sit down Ku‘u, sit down and spend some time with me and your uncles. [Have a beer with us].” Do you think maybe [you would insert her distraction] somewhere around there?

Participant Pyro: Yeah, she would have like, she could have like umm, a stomachache or something, like tell her dad, “Oh I have a stomachache, I gotta go take medicine or something.”

Facilitator: Okay.

Participant Kurt: [Referencing the scripted behavior] I don’t think she would rat out her dad. “Oh, look what dad gave me.”

Facilitator: You don’t think that – that she would do that. She wouldn’t say – You don’t think she’d say, “Mom look what dad gave me” that way? You don’t think she would yell it out?

Participant Pyro: No.

Participant Mario: She was just like walk back in the house and whisper to her mom.

This quote, as well as other quotes, suggest that they would want their mother to know what happened to them if they were in a similar situation, but would not want their father or uncles to know they were the one who intentionally told her. The boys agreed that there would be a “big scene” if Ku‘u announced the offer in front of family members, and the other family members would become angry with her. “Pyro” describes what could happen to Ku‘u if she announced her father's offer in front of all of the family members.

Participant Pyro: Yeah the dad might get pissed off, come in, “eh, why you go tell mom?” Like, “Oh, you tell mom.” Yeah, like she gonna get real pissed.

The boys also discussed other nonconfrontational or indirect behaviors that Ku‘u could use to inform the mother character in “Pulehu” about her father’s alcohol offer. The intent behind these behaviors was to call attention to the father’s offer in a seemingly unintentional manner, so as to prevent Ku‘u from getting in trouble by her father. One participant suggested that Ku‘u should pretend she got hurt, so as to call her mother's attention to her father’s and uncles’ behavior.

Facilitator: So, okay, well let’s go back to Kurt. What you were saying, umm, so you think that in one situation what might happen is that um, the mom would overhear this interaction between the, between Ku‘u and Kana, there would be, she’d see this drug offer occurring and she would come out, finally trying to figure out what’s going on.

Participant Kurt: Yeah.

Participant Pyro: Yeah.

Participant Mario: Yeah.

Participant Kurt: Or she would just umm, she’d just uh like scream “Ahh! My toe” or something and the mom would walk outside and see what the stuff.

Participant Pyro: Oh yeah, that’s a pretty good idea, like she like, I don’t know, like something probably like injure her like somehow, then the mom comes out, sees everything, all the beer, the cigarettes. “Hey what you guys doing?” You know?

The boys also brainstormed different ways in which Ku‘u would be able to leave the situation without upsetting her father. They even described the option of Ku‘u pretending to drink the beer, followed by covertly disposing of it, so that her father wouldn't get mad at her.

Participant Pyro: Yeah, 'cause she like, after a while, she fake sips it then, like “Oh, I have to go the bathroom.”

Facilitator: So, she has to go to the bathroom and so what does she do? She takes the beer to the bathroom with her?

Participant Kurt: Yeah, that’s how she is gonna do it.

Participant Pyro: No, she just keeps it there. 'Cause after a while she fakes sip it. Like, yeah.

Similar to adult family members, the boys also endorsed non-confrontational or indirect drug resistance strategies with cousins and siblings. In “Kanikapila Invite,” the protagonist in the script receives an offer to hang out and do drugs with his older cousin and his cousin's friends. The boys described the use of socially acceptable excuses with cousins, so that they could preserve their relationships with them.

Participant Rerun: Or, [you can tell your cousin] my friend get one party. [The protagonist] is going to somebody else’s party.

Facilitator: Oh, he’s going to somebody else’s party?

Video Director: That’s kind of a cool one, even though he lying, yeah? Just for make him kinda like, make it kinda like a cooler excuse. Like, “Oh, I already going to one party. I already have a party to go to.” That’s kinda interesting.

Facilitator: Okay. Alright. What do you think of that, Daredevil? What do you think of that excuse? Is that a good one?

Participant Daredevil: Yeah.

In discussing “Oh Brother,” the boys similarly indicated that they did not think the protagonist (Cora) would “rat out” her brother by saying, “Mom, look what he gave to me!” after he offers her marijuana. They suggested that the behaviors would be more covert, so as to preserve the relationship between Cora and her brother.

Participant Turbo: The second one [referring to the response “Mom, look what he gave to me!”], I-I don’t know, I don’t-I don’t really see a sibling like, trying to rat out their other, older brother, about smoking weed, like, at least not-not how she’s doing it.

Facilitator: Okay, so if she was gonna rat out her brother, if it’s not done this way, how do you think she would do it that would be more realistic?

Participant Turbo: Like, I don’t know, maybe she and her mom are having another conversation, kind un-

Participant Spongebob: [Interrupts] Privately.

Participant Turbo: Yeah.

Participant Spongebob: She won’t say it in front of the brother.

Girls’ Relational Considerations in Drug Resistance

Similar to the boys’ groups, the girls also endorsed maintaining relational harmony in drug-related problem situations with their family members. However, while the boys primarily defined relational harmony as ensuring that family members were not angry with the youths who received drug offers, the girls primarily defined relational harmony as ensuring that family members were not mad at each other. The girls rarely mentioned a fear of “getting in trouble” in the scripts. Rather, the girls described more of a holistic concern about interpersonal conflict among family members. For example, the girls expressed concern that the mother character in “Pulehu” would be angry at the father and uncles if she found out that they offered Ku‘u alcohol. Their response suggests that long-term negative relational consequences could result if the mother character found out about the offer.

Participant Dakota: When she tells her mom, and then her mom comes out, you can kinda tell she’s mad.

Facilitator: Okay, Glam, what do you think about this situation?

Participant Glam: Oh, um, I think that the dad would get in trouble, 'cause that’s like his daughter and the mom’s gonna be really upset with him.

Facilitator: Oh okay. Okay, um, Laverne, what did you think about it?

Participant Laverne: Her mom and her dad might have more fights now, and the mom will start not trusting the dad.

The girls also endorsed more direct drug refusal responses to family members, if they felt that the response might prevent discord among other family members. The girls seemed to not be as concerned about family members being mad at the youth protagonist for rejecting the offer.

For example, in “Pulehu,” they expressed more concern about keeping adult family members out of trouble with the mother character, rather than the father being angry at Ku‘u.

Participant Cutie: [Reading the script] Dad, nuff, nuff with the beers already. Mom’s gonna get, mom’s gonna be pissed off if she sees how drunk you are.

Participant Cutie: I would have [also] told him that mom might be mad if [she found out] he give [sic] me a beer.

Another direct refusal strategy endorsed by the girls was the use of empathy. In “Pulehu,” the girls supported Ku‘u’s approach of expressing empathy toward the father character while directly refusing the offer, rather than using nonconfrontational methods (e.g., accepting the offer for alcohol and then getting rid of it without the father knowing about it).

Facilitator: Um, okay. So then it, it sounds like all of you guys would be some level of discomfort, fear, or I think you said feel scared, confused, pressured, um and I think you expressed the same kind of thing.

Participant Dakota: Empathy.

Facilitator: Oh empathy. Yeah, um okay, so then what do you think Ku‘u should do in this situation? How would she behave in this situation?

Participant Cutie: Um, she would like, tell her dad guys that she doesn’t wanna drink. And that she wanna just listen, like talk with them instead.

While directly refusing the offer might be perceived as insubordination by the father, they felt that this approach would help to maintain relational harmony among other family members. The girls also expressed consideration of relational harmony among others when responding to drug offers from cousins. For example, in “Pā‘ina,” the girls discussed different ways the protagonist could directly refuse drug offers while simultaneously pointing out the relational risks of substance use (i.e., fighting) to their cousins, so that they would reconsider their use as well.

Facilitator: So she looks, Kammy looks around [pause]. Okay, and what is she going to say? Anything else? She’s going to say something else?

Participant Candy: “Look at those people over there having fun instead of getting all bus [local slang for “drunk”].”

Facilitator: So “Look at those people having fun instead of getting bus.”

Participant Candy: Yeah.

Facilitator: Okay, how else? That’s one way of saying [it]. What else can we say?

Participant Candy: “We should have a fun time instead of ruining our night.”

Facilitator: “We should have a fun time instead of…?”

Participant Candy: “…ruining our night.” Because most drunk people get into fights.

Discussion

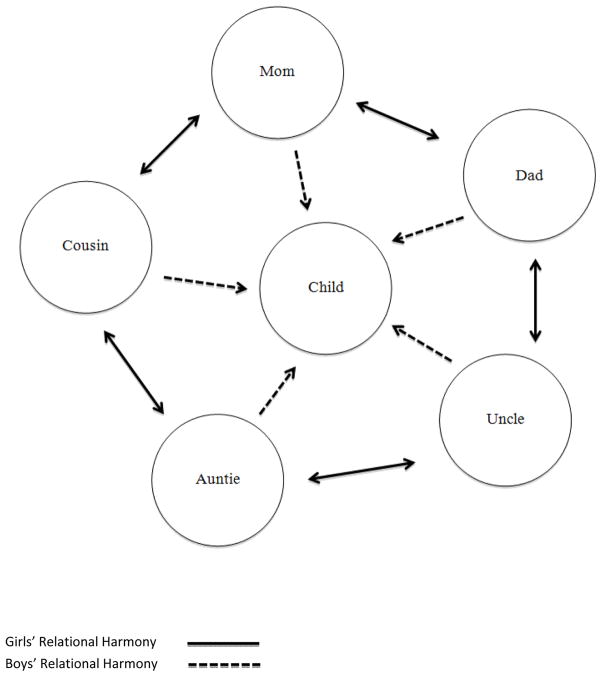

The purpose of this study was to examine the role of relational harmony in the selection and use of drug resistance strategies for rural Native Hawaiian youth. Within drug-related problem situations, youth participants emphasized the importance of maintaining relational harmony among family members when refusing drug and/or alcohol offers from them. This is consistent with the ‘ohana structure in Native Hawaiian culture, and the emphasis on relational interconnectedness within the family (McCubbin & Marsella, 2009; Mokuau, 2011). The youth participants recognized the challenges in balancing drug refusal and relational harmony among family members, but also considered the importance of both of these goals in dealing with drug-related problem situations. Although boys and girls in the study emphasized the importance of relational harmony within the family, they perceived it in different ways. The boys in the study defined relational harmony primarily as keeping their family members from being mad at them, while the girls defined it primarily as keeping the family members from being mad at one another. These differences are depicted in Figure 1. In this figure, the relational focus for boys is directed toward the youth, while the focus for girls is between the family members.

Figure 1.

Gender Differences in Relational Harmony of Rural Hawaiian Youth

These gender specific findings are consistent with the principles of relational-cultural theory (Comstock et al.,2008; West, 2005), which emphasize the role of culture-based relational disconnections between significant individuals in the development of women and girls’ psychological disorders. According to this theory, girls in the study may have considered resistance strategies that would mitigate discord among significant family members in their lives, in order to prevent relational disconnections among those family members. The present findings are also are consistent with gender-specific research on other indigenous populations, which has described the unique and intense relational challenges that indigenous girls face when offered drugs from immediate and extended family members (Dixon-Rayle et al., 2006; Okamoto et al., 2010). Specifically, these studies found that indigenous girls experienced drug-related problem situations with family members more frequently than indigenous boys, and that they had more difficulty in dealing with these situations than their male counterparts. Consistent with these studies, the findings in the present study suggest that Hawaiian girls are more sensitive to the influence and importance of their relational contexts when dealing with drug-related problem situations, while their male counterparts may have been more limited in understanding the importance of these contexts.

Implications for Social Work Practice

Our findings suggest that it may be important to address the gender-specific considerations that Hawaiian youth may have when using drug refusal strategies, which should be reflected in culturally specific drug prevention and intervention programs. These considerations may relate to the gender-specific motivations for these youth to use these strategies. Specifically, discussions and/or activities in prevention and intervention programs might be tailored to address more holistic relational goals within the family (i.e., having all family members getting along with each other) for girls, and more instrumental relational goals (i.e., having the adults not being mad at the youth) for boys. In order to effectively address relational harmony within the family in drug-related problem situations, our findings suggest that drug prevention and intervention programs for rural Hawaiian youth must incorporate both of these types of goals.

More broadly, this study may also have practice implications for youth residing in rural communities outside of Hawai‘i. Rural communities have been characterized as close-knit and interconnected, with both biological and ascribed family members (Okamoto et al., 2009; Strasser, 2003). In these settings, the need for skills to balance relational harmony and drug refusal are necessary and relevant. This may include the use of non-confrontational drug resistance strategies (e.g., avoiding situations where drugs and/or alcohol use are prevalent) or the use of empathy and concern for the well-being of other family members. These types of strategies are in contrast to those which may achieve the goal of drug refusal, but at the risk of jeopardizing important and significant relationships with family members (e.g., saying “no”). Confrontational and/or direct drug resistance strategies may be perceived as disrespectful, particularly when drug offerers are adult family members.

Limitations of the Study

There were several limitations to this study. First, this study utilized hypothetical drug-related problem scenarios in which to examine drug resistance strategies. While these scenarios were established and validated by Hawai‘i Island youth as both realistic and relevant in prior years, they were not based on first-hand accounts of drug offers by the youth participating in the study. Second, the place-based nature of this study may restrict its transferability to Pacific Islands other than Hawai‘i Island, as well as to the Continental U.S. Finally, sampling for this study may have been affected by selection biases. Despite required measures to ensure participant confidentiality and anonymity of qualitative data, parents of youth in higher-risk environments may not have allowed their children to participate in the study, due to concerns that their children may self-disclose their family's substance use.

Also notable are the limitations related to school-based interventions evolving from pre-prevention efforts such as those described in this study. By focusing on promoting drug resistance skills and strategies, one could argue that the resulting intervention places the burden of change on those who are most vulnerable (i.e., rural Hawaiian youth). These types of interventions may also have limited ability to affect youths’ families, schools, and the broader community. Future social work and prevention research should examine culturally specific, school-based prevention efforts in the context of multi-level prevention interventions (i.e., interventions that focus on at least two ecosystemic levels, such as the individual, school climate, family, and/or community). The development and evaluation of these types of interventions have recently been prioritized for funding by the National Institutes of Health, and are consistent with the principles of ecological systems theory within social work practice.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the literatures in rural, Pacific Islander, and indigenous health. It emphasizes the interpersonal and contextual considerations that impact drug refusal strategies for rural Hawaiian youth, contributing to our understanding of the relevance and feasibility of drug prevention curricula for these youth. In order to create effective prevention and social work interventions for these youth, the role of relational harmony among family members should be considered alongside the goal of drug refusal. Further, gender differences in the consideration of relational harmony found in the present study suggest the need for gender- and culture-specific prevention and social work interventions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (R34 DA031306), with supplemental funding from the Trustees’ Scholarly Endeavors Program, Hawai‘i Pacific University, and was completed for partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master in Social Work program at Hawai‘i Pacific University. The authors would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their assistance with data collection for this study: Ay-Laina Dinson, Jessica Mabanag, Nicholas Maez, Latoya L. McClain, and Matt Yamashita.

Footnotes

In NVivo, “coverage” refers to the amount of text in a transcript that is devoted to a specific code.

Contributor Information

Kaycee Bills, Hawai‘i Pacific University

Scott K. Okamoto, Hawai‘i Pacific University

Susana Helm, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa

References

- Accountability Resource Center Hawai‘i. School accountability: School status and improvement report. 2012 Retrieved March 22, 2013, from http://arch.k12.hi.us/school/ssir/2012/hawaii.html.

- Beauvais F, Trimble JE. The effectiveness of alcohol and drug abuse prevention among American-Indian youth. In: Sloboda Z, Bukoski WJ, editors. Handbook of drug abuse prevention: Theory, science, & practice. New York: Kluwer; 2003. pp. 393–410. [Google Scholar]

- Comstock DL, Hammer TR, Strentzsch J, Cannon K, Parsons J, Salazar G. Relational-cultural theory: A framework for bridging relational, multicultural, and social justice competencies. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2008;86:279–287. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon Rayle A, Kulis S, Okamoto SK, Tann SS, LeCroy CW, Dustman P, Burke AM. Who is offering and how often? Gender differences in drug offers among American Indian adolescents of the Southwest. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2006;26(3):296–317. doi: 10.1177/0272431606288551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne MP, Yeo MA, Keane J, Elkins DB. Substance use by Indigenous and non-Indigenous primary school students. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2000;24(5):546–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2000.tb00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C, Giroux D, Okamoto SK. A review of the literature on Native Hawaiian youth and drug use: Implications for research and practice. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2010;9(3):153–172. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2010.500580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebert D, Nahulu L, Hishinuma E, Bell C, Yuen N, Carlton B, … Johnson R. Cumulative effect of family environment on psychiatric symptomatology among multiethnic adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:34–42. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins EH, Cummins LH, Marlatt GA. Preventing substance abuse in American Indian and Alaska Native youth: Promising strategies for healthier communities. In: Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K, editors. Addictive behaviors: New readings on etiology, prevention, and treatment. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2008. pp. 575–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heavyrunner-Rioux AR, Hollist DR. Community, family, and peer influences on alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drug use among a sample of Native American youth: An analysis of predictive factors. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2010;9(4):260–283. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2010.522893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm S, Lee W, Hanakahi V, Gleason K, McCarthy K, Haumana Using photovoice with youth to develop a drug prevention program in a rural Hawaiian community. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2015;22(1):1–26. doi: 10.5820/aian.2201.2015.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurdle DE, Okamoto SK, Miles B. Family influences on alcohol and drug use by American Indian youth: Implications for prevention. Journal of Family Social Work. 2003;7(1):53–68. doi: 10.1300/J039v07n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lauricella M, Valdez JK, Okamoto SK, Helm S, Zaremba C. Culturally grounded prevention for minority youth populations: A systematic review of the literature. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10935-015-0414-3. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin LD, Marsella A. Native Hawaiians and psychology: The cultural and historical context of indigenous ways of knowing. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15(4):374–387. doi: 10.1037/a0016774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokuau N. Culturally based solutions to preserve the health of Native Hawaiians. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2011;20:98–113. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2011.570119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mokuau N, Garlock-Tuiali‘i J, Lee P. Has social work met its commitment to Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders? A review of the periodical literature. Social Work. 2008;53(2):115–121. doi: 10.1093/sw/53.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK. Current and future directions in social work research with Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2011;20(2):93–97. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2011.569979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S. Eliminating health disparities through culturally grounded social work research: Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) youth prevention. Paper presented at the 61st Annual Program Meeting of the Council on Social Work Education; Denver, CO. 2015. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Giroux D, Edwards C, Kulis S. The development and initial validation of the Hawaiian Youth Drug Offers Survey (HYDOS) Ethnicity & Health. 2010;15(1):73–92. doi: 10.1080/13557850903418828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Giroux D, Kaliades A, Kawano KN, Kulis S. A typology and analysis of drug resistance strategies of rural Native Hawaiian youth. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2010;31(5–6):311–319. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0222-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Giroux D, Kaliades A. “I no like get caught using drugs”: Explanations for refusal as a drug-resistance strategy for rural Native Hawaiian youths. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2011;20(2):150–166. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2011.570131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Po‘a-Kekuawela K, Chin CIH, Nebre LRH. Community risk and resiliency factors related to drug use of rural Native Hawaiian youth: An exploratory study. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2009;8(2):163–177. doi: 10.1080/15332640902897081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Kulis S, Helm S, Edwards C, Giroux D. Gender differences in drug offers of rural Hawaiian youths: A mixed-methods analysis. Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work. 2010;25(3):291–306. doi: 10.1177/0886109910375210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Kulis S, Helm S, Edwards C, Giroux D. The social contexts of drug offers and their relationship to drug use of rural Hawaiian youths. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2014;23(4):242–252. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2013.786937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Kulis S, Helm S, Lauricella M, Valdez JK. An evaluation of the Ho‘ouna Pono curriculum: A pilot study of culturally grounded substance abuse prevention for rural Hawaiian youth. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2016;27(2):815–833. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Holleran Steiker LK, Dustman PA. A continuum of approaches toward developing culturally focused prevention interventions: From adaptation to grounding. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2014;35(2):103–112. doi: 10.1007/s10935-013-0334-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Po‘a-Kekuawela K, Okamoto SK, Nebre LRH, Helm S, Chin CIH. ‘A‘ole Drugs! Cultural practices and drug resistance of rural Hawaiian youths. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2009;18(3):242–258. doi: 10.1080/15313200903070981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards L. Handling Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide. London: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer G. Family functioning in families with alcohol and other drug addiction. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand. 2011;37:135–51. [Google Scholar]

- Silva NK. Aloha betrayed: Native Hawaiian resistance to American colonialism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Strasser R. Rural health around the world: Challenges and solutions. Family Practice. 2003;20(4):457–463. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tobler NS, Stratton HH. Effectiveness of school-based drug prevention programs: A meta-analysis of the research. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 1997;18(1):71–128. [Google Scholar]

- Tribal Evaluation Workgroup. A Roadmap for Collaborative and Effective Evaluation in Tribal Communities. Washington D.C: Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. State & County QuickFacts: Hawaii County, HI. 2014 Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/15/15001.html.

- Weitzman EA. Software and qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- West CK. The map of relational-cultural theory. Women & Therapy. 2005;28(3):93–110. doi: 10.1300/J015v28n03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]