Abstract

Background:

The prevalence of Brugada ECG pattern (BrEP) is different in different regions, and its mean prevalence over the world is unknown. The risk of people with BrEP for death remains unknown. We performed a meta-analysis to determine the prevalence of BrEP and risk ratio (RR) for death.

Methods:

Relevant studies published between July 1, 2000 and August 20, 2016, which contain prevalence and RR for all-cause death and cardiac death, were included. The prevalence and RR are analyzed using meta-analysis.

Results:

We finally retrieved 24 studies of the prevalence for BrEP and 5 studies of the RR for all-cause death and cardiac death. The worldwide mean prevalence of BrEP is 0.4%, with highest in Asia (0.9%) and lowest in North America (0.2%). Additionally, the mean prevalence in male is 0.9%, whereas it is 0.1% in female. The RR of BrEP for all-cause death is 0.78 (95% confidence interval 0.45–1.37), and for cardiac death it is 0.92 (95% confidence interval 0.23–3.66).

Conclusion:

The prevalence of BrEP is about 0.4% around the world with different prevalence in region and sex. Our study shows that BrEP may not be taken as a predictor of all-cause death and cardiac death.

Keywords: Brugada ECG pattern, Brugada syndrome, risk ratio, sudden cardiac death, ventricular fibrillation

1. Introduction

Since 1992, when Brugada syndrome (BrS) was first described,[1] the BrS has been universally recognized as a cause of arrhythmia, syncope, ventricular fibrillation (VF), and sudden cardiac death (SCD) without structural heart disease.[2] BrS is responsible for up to 20% of SCDs (worldwide) in patients with structurally normal hearts.[3,4] The prevalence of Brugada ECG pattern (BrEP) is different in region and sex, and such differences range greatly with a greater prevalence in Asians and in men.[5] However, its mean prevalence over the world is unknown.

The typical ECG of BrS is known as the BrEP, which is characterized by right bundle-branch block and ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads (V1–V3).[2] Based on the differences of the ECG patterns (eg, the extent of ST-segment elevation), BrEP can be divided into 3 types.[6] BrS might show a variable ECG presentation that includes the 3 types at different times.[2,5,6] According to the 2013 consensus report, the type I Brugada ECG pattern is the main criterion for the diagnosis of the BrS, whereas types II and III are at low risk.[7] It is also known that some physiologic causes such as normal variant, incomplete right bundle-branch block, and pathologic causes such as pulmonary hypertension and hyperkalemia can result in BrEP.[8,9] The diagnosis of BrS has been suggested to combine the ECG patterns and the clinical symptoms.[5,6]

The risk for people with BrEP remains controversial. The incidence of VF, SCD, or syncope differs greatly, especially between patients with and without a history of SCD or syncope, and may be relative high in Asian patients.[5] This study aims to identify regional prevalence for BrEP and the risk of death in people with BrEP worldwide.

2. Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was launched based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. There are no ethical issues involved in our study as our data were based on published studies.

2.1. Definition of Brugada ECG

Brugada ECG has been divided into 3 types, defined as follows[6]:

Type I: Prominent coved ST-T segment with a J-wave amplitude, or ST-segment elevation ≥2 mm at the peak with a negative T-wave without isoelectric separation followed.

Type II: High take-off ST segment with a J-wave amplitude ≥2 mm followed by gradually decreasing ST-segment elevation (≥1 mm above the baseline), and a biphasic or positive T-wave that arises saddle-back configuration.

Type III: Right precordial ST-segment elevation <1 mm of a saddle-back type or/with coved type.

2.2. Study selection

We performed a comprehensive and systematic search of retrospective, prospective, randomized, or nationwide studies in PubMed, EMBASE, Medline, and The Cochrane Library using terms “Brugada ECG patterns,” “Brugada syndrome,” “prevalence of Brugada,” “death,” “prognosis,” “mortality,” and “meta-analysis.” Only the studies whose patients have BrEP will be included in our study. As the prevalence of BrEP has been estimated about 0.5%,[10] we only choose the studies whose total number of the patients is more than 200. And, as we hope to find out the regional prevalence of BrEP, the studies are also limited to regional investigations which were made in a random group of people.

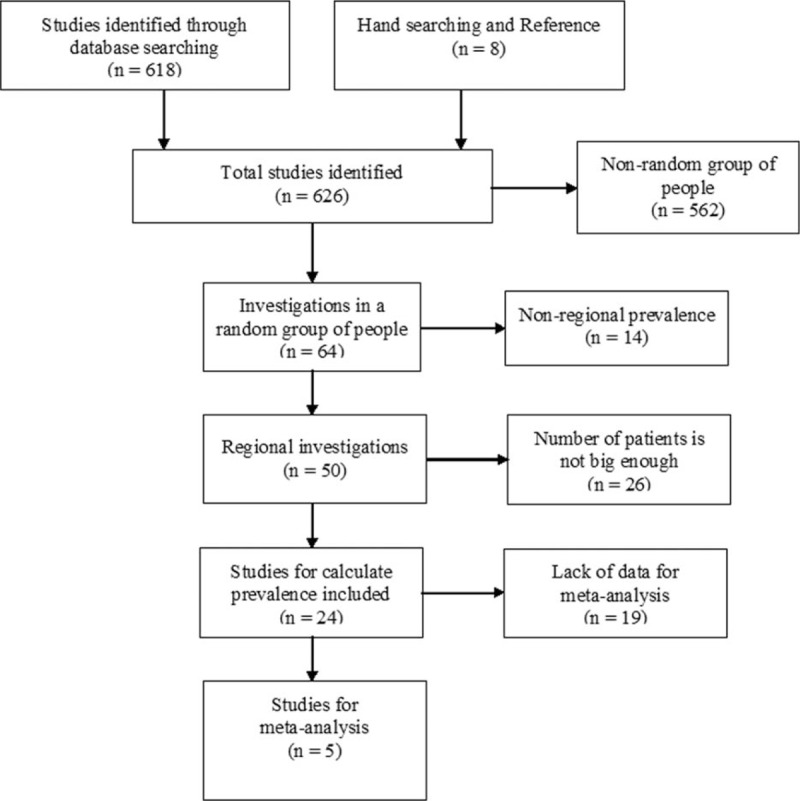

The detailed selection process is listed in Fig. 1. We searched 626 studies totally, but only 24 studies can be included for the calculation of prevalence. Only 5 of the 24 studies can be used for meta-analysis of risk ratio (RR). According to the endpoint, we performed meta-analysis of the risk of BrEP for all-cause death and cardiac death.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and study selection.

2.3. Data extraction

From each retrieved study, the following data were extracted: name of the lead investigator and year of the paper, the region or country where the study was performed, sample size, proportions of men and women, the mean age, follow-up time, total prevalence, male prevalence and female prevalence, types of BrEP, the primary and secondary endpoints, RR, or hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

The following criteria are used for the assessment of the risk of bias and methodological quality: definition of BrEP, sample size, study design, inclusion criteria, sex ratio, and the duration of the follow-up.

2.4. Data synthesis

With the basis of random-effects model developed by DerSimonian and Laird, the Begg test, which has been demonstrated with Cochran Q test and I2 statistic of the homogeneity of the results, was used for the evaluation of publication bias. And finally, we omitted each study 1 at a time to perform sensitivity analysis to examine the influence of each study on the pooled estimation. RR and 95% CI were calculated or recalculated for each study.[11]

Chi-square-based Q test was performed for the analysis of the heterogeneity of reported prevalence with 95% CI.[12,13] After the heterogeneity test, we found important variations between studies. So, with the purpose of getting better results, we used the random-effects model[14,15] for the estimation of the prevalence of BrEP.

The results are shown in forest plots (the point estimations and their 95% CI). Statistical significance was set at a P value <0.05, and all tests performed were 2-sided.[16] Meta-analysis was performed using Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

3. Results

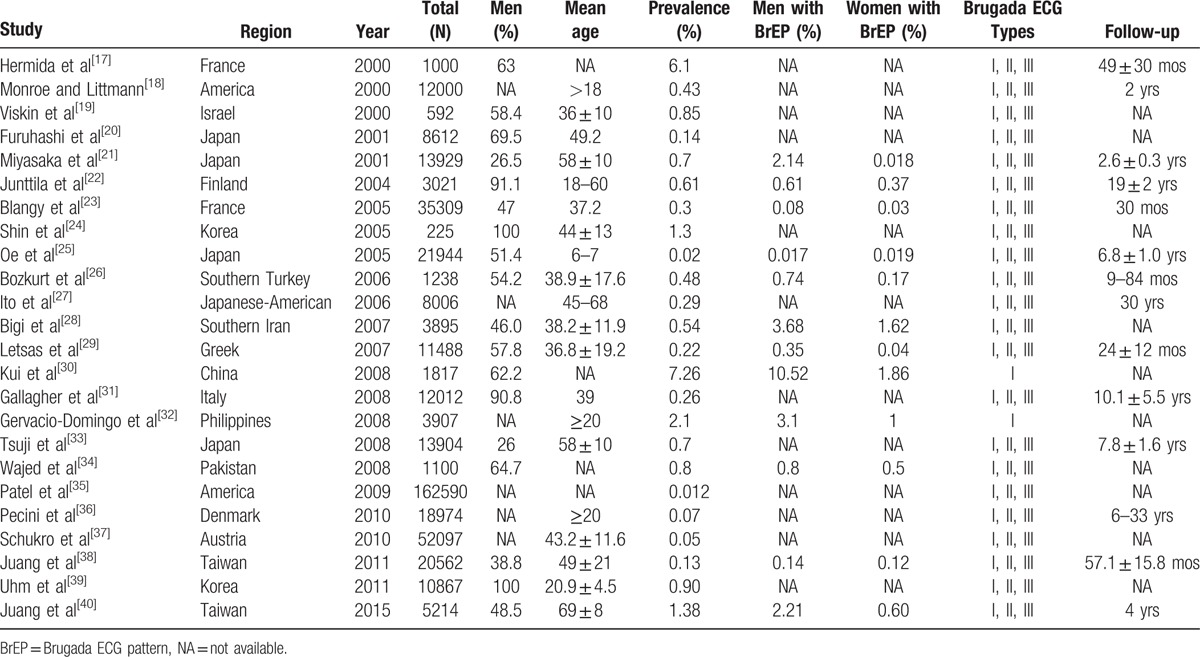

After search and selection, we finally found 24 articles to be included in our study (Table 1).[17–40] Only 2 studies[30,32] have included merely type I BrEP, the rest studies have included all the 3 types of ECG patterns. Eleven of the 24 studies[21–23,25,26,28–30,34,38,40] have also studied the sex differences for the prevalence of BrEP. Five studies[21,27,33,38,40] have studied the RR of all-cause death and cardiac death for the patients with BrEP. All the 5 studies[21,27,33,38,40] we used for meta-analysis of RR included all the 3 types ECG patterns.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of prevalence of BrEP in each study.

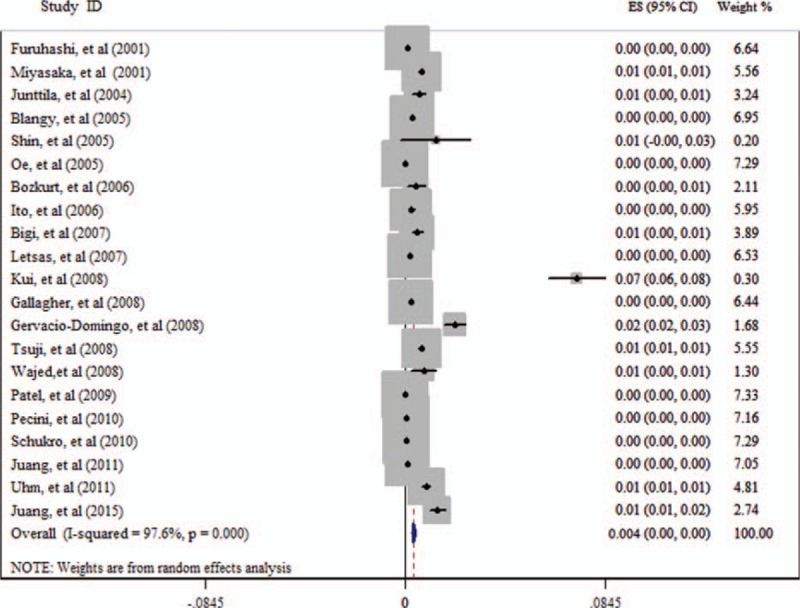

All these studies cover an extensive area all over the world, including Asia, Europe, and North America. According to these studies, the mean prevalence of BrEP across the world is 0.4% (Fig. 2, Table 2). The results of regional prevalence of BrEP are presented in Table 2. The prevalence of BrEP is 0.9%, 0.3%, and 0.2% in Asia,[19–21,24,25,28,30,32–34,38–40] Europe,[17,22,23,26,29,31,36,37] and North America,[18,27,35] respectively (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Result of the mean global prevalence of Brugada ECG pattern (BrEP).

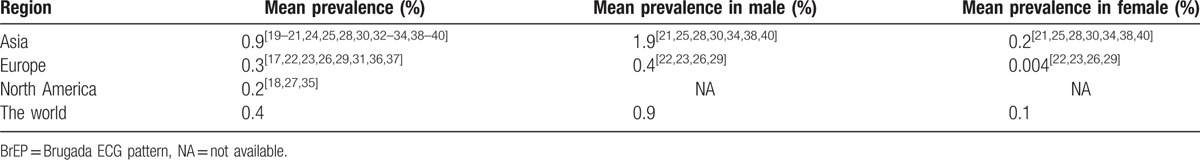

Table 2.

Mean prevalence and mean prevalence of different sex of BrEP in each region.

Eleven articles[21–23,25,26,28–30,34,38,40] have studied the sex differences of the prevalence of BrEP (Table 2). The mean prevalence of BrEP in male is 0.9%, whereas that in female is 0.1% in the world. Additionally, the prevalence in male is always higher than that in female in all regions. The prevalence of both male (1.9%) and female (0.2%) is the highest in Asia.

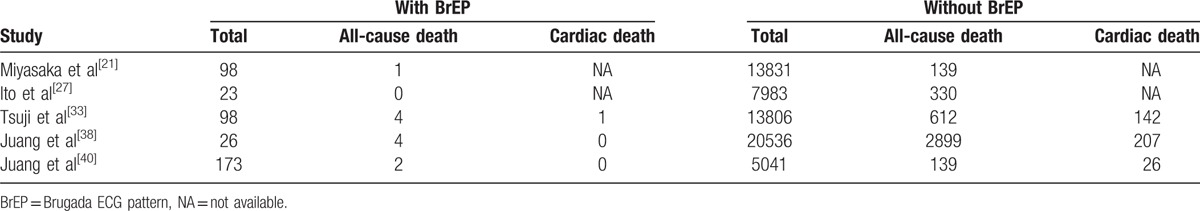

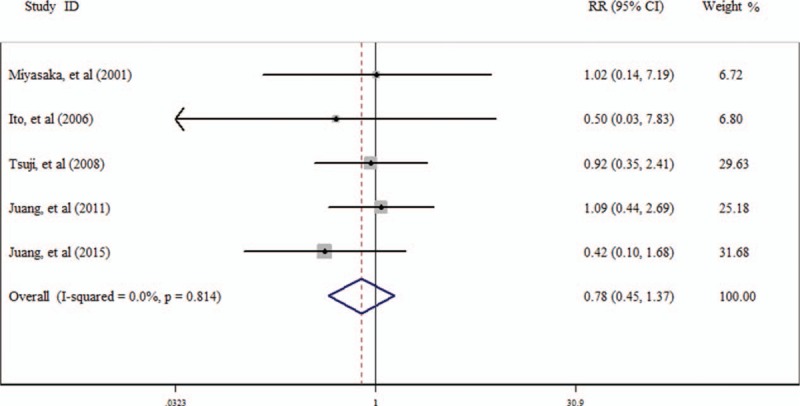

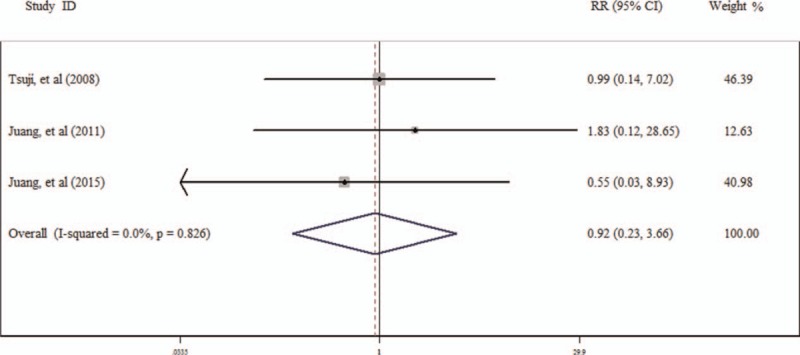

Five studies[21,27,33,38,40] have studied the RR of all-cause death and cardiac death for the people with BrEP (Table 3). The RR of BrEP for all-cause death is 0.78 (95% CI 0.45–1.37; Fig. 3), and for cardiac death it is 0.92 (95% CI 0.23–3.66; Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Summary characteristics of death ratio of people with BrEP and without BrEP.

Figure 3.

Result of the risk ratio (RR) of Brugada ECG pattern (BrEP) for all-cause death.

Figure 4.

Result of the risk ratio (RR) of Brugada ECG pattern (BrEP) for cardiac death.

4. Discussion

This study yielded the following novel findings: the prevalence of BrEP is about 0.4% around the world with different prevalence in region and sex; BrEP may not be taken as a predictor of all-cause death and cardiac death.

The right bundle-branch block and ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads (V1–V3) are the main characteristics of BrEP.[2] BrS has been considered as a cause of arrhythmia, syncope, VF, and SCD without structural heart disease.[2] According to the 2013 consensus report, the finding of type I Brugada ECG pattern is the basis of the diagnosis of BrS.[7] However, some experts have suggested that either symptoms such as agonal nocturnal respiration, cardiac arrest, unexplained syncope, and documented ventricular tachycardia/VF, or positive family history such as diagnosed BrS in a first-degree relative or unexplained SCD <45 years be included in the diagnostic criteria.[5] If a type I Brugada ECG pattern is observed without any clinical criteria, this should be referred to as “idiopathic BrEP” and not as BrS.[41,42]

The present study shows that the prevalence of BrEP is significantly different between Asia, Europe, and North America (Table 2). It shows that the racial differences, geographical differences, and regional tradition may play roles in the prevalence of BrEP. The prevalence in Asia is much higher than that in the other places of the world, over 4 times as much as it is in North America. And the prevalence in Europe is close to the average level of the world, with a prevalence of 0.3%. Our study shows that men are over 4 times easier to get BrEP than women (Table 2). These results are consistent with previous studies,[5,6,43] and we confirm the existence of the regional and sex difference in prevalence of BrEP.

Our study shows that the RR of BrEP for all-cause death and cardiac death are 0.78 and 0.92, respectively, for people with BrEP. It shows that BrEP may not be taken as a predictor of all-cause death and cardiac death. However, according to the previous observations, the people with BrEP are at high risk of sudden death.[44–47] These studies are mainly hospital-based studies. The people included in these studies have symptoms like syncope and VF, or history of SCD. The studies we included are community-based studies[21,40] and population-based studies,[27,33,38] in which the participants may not have symptoms or history as mentioned above.

Another possible reason for the negative result of present study is that all the studies[21,27,33,38,40] we used for meta-analysis of RR included all the 3 types of ECG patterns. Previous studies showed that type I BrEP is at high risk, whereas types II and III are at low risk.[2,6,42] Further studies are needed to estimate type I BrEP for all-cause death and cardiac death.

4.1. Limitations

Our study has the following limitations:

-

1.

The subjects in our study are mostly from Asia and their parameters could not represent the state of the whole population worldwide.

-

2.

We included the people with BrEP into our study, and the symptoms such as cardiac arrest and unexplained syncope were not considered as criteria. Further studies based upon both BrEP and clinical symptoms, or history, are needed.

-

3.

Most of the studies in our research included all the 3 ECG patterns. Further studies which focus on type I BrEP are needed.

5. Conclusions

The prevalence of BrEP in the general population is about 0.4%, whereas it differs extensively in terms of region and sex. BrEP may not be taken as a predictor of all-cause death and cardiac death.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BrEP = Brugada ECG pattern, BrS = Brugada syndrome, RR = risk ratio, SCD = sudden cardiac death, VF = ventricular fibrillation.

XQ and SL contributed equally to the article, so they should be considered as the co-first authors.

Authors’ contributions: QT and XQ conceived and designed the experiments; SL and RL performed the experiments; SL, RL, KZ, and XW analyzed the data; QT and SL contributed to the writing of the manuscript; and XQ revised the manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by the grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81301053).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;20:1391–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Brugada P. Brugada syndrome: more than 20 years of scientific excitement. J Cardiol 2016;67:215–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zheng J, Zhou F, Su T, et al. The biophysical characterization of the first SCN5A mutation R1512W identified in Chinese sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chen Z, Mu J, Chen X, et al. Sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome in central China (Hubei): a 16-year retrospective study of autopsy cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Adler A. Brugada syndrome: diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Curr Opin Cardiol 2016;31:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Berne P, Brugada J. Brugada syndrome 2012. Circ J 2012;76:1563–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, et al. HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart Rhythm 2013;10:1932–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bayes de Luna A, Brugada J, Baranchuk A, et al. Current electrocardiographic criteria for diagnosis of Brugada pattern: a consensus report. J Electrocardiol 2012;45:433–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chung EH. Brugada ECG patterns in athletes. J Electrocardiol 2015;48:539–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gehi AK, Duong TD, Metz LD, et al. Risk stratification of individuals with the Brugada electrocardiogram: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2006;17:577–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Xu R, Ding S, Zhao Y, et al. Autologous transplantation of bone marrow/blood-derived cells for chronic ischemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol 2014;30:1370–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ding S, Du YP, Lin N, et al. Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 on major cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Cardiol 2016;222:957–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ding S, Xu L, Yang F, et al. Association between tissue characteristics of coronary plaque and distal embolization after coronary intervention in acute coronary syndrome patients: insights from a meta-analysis of virtual histology-intravascular ultrasound studies. PLoS One 2014;9:e106583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lyu T, Zhao Y, Zhang T, et al. Natriuretic peptides as an adjunctive treatment for acute myocardial infarction: insights from the meta-analysis of 1,389 patients from 20 trials. Int Heart J 2014;55:8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lyu T, Zhao Y, Zhang T, et al. Effect of statin pretreatment on myocardial perfusion in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol 2013;36:E17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yeung HM, Hung MW, Lau CF, et al. Cardioprotective effects of melatonin against myocardial injuries induced by chronic intermittent hypoxia in rats. J Pineal Res 2015;58:12–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hermida JS, Lemoine JL, Aoun FB, et al. Prevalence of the brugada syndrome in an apparently healthy population. Am J Cardiol 2000;86:91–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Monroe MH, Littmann L. Two-year case collection of the Brugada syndrome electrocardiogram pattern at a large teaching hospital. Clin Cardiol 2000;23:849–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Viskin S, Fish R, Eldar M, et al. Prevalence of the Brugada sign in idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and healthy controls. Heart 2000;84:31–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Furuhashi M, Uno K, Tsuchihashi K, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic ST segment elevation in right precordial leads with right bundle branch block (Brugada-type ST shift) among the general Japanese population. Heart 2001;86:161–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Miyasaka Y, Tsuji H, Yamada K, et al. Prevalence and mortality of the Brugada-type electrocardiogram in one city in Japan. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:771–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Junttila MJ, Raatikainen MJ, Karjalainen J, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of subjects with Brugada-type ECG pattern in a young and middle-aged Finnish population. Eur Heart J 2004;25:874–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Blangy H, Sadoul N, Coutelour JM, et al. [Prevalence of Brugada syndrome among 35,309 inhabitants of Lorraine screened at a preventive medicine centre]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 2005;98:175–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Shin SC, Ryu HM, Lee JH, et al. Prevalence of the Brugada-type ECG recorded from higher intercostal spaces in healthy Korean males. Circ J 2005;69:1064–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Oe H, Takagi M, Tanaka A, et al. Prevalence and clinical course of the juveniles with Brugada-type ECG in Japanese population. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2005;28:549–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bozkurt A, Yas D, Seydaoglu G, et al. Frequency of Brugada-type ECG pattern (Brugada sign) in Southern Turkey. Int Heart J 2006;47:541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ito H, Yano K, Chen R, et al. The prevalence and prognosis of a Brugada-type electrocardiogram in a population of middle-aged Japanese-American men with follow-up of three decades. Am J Med Sci 2006;331:25–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bigi MA, Aslani A, Shahrzad S. Prevalence of Brugada sign in patients presenting with palpitation in southern Iran. Europace 2007;9:252–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Letsas KP, Gavrielatos G, Efremidis M, et al. Prevalence of Brugada sign in a Greek tertiary hospital population. Europace 2007;9:1077–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kui C, Congxin H, Xi W, et al. Characteristic of the prevalence of J wave in apparently healthy Chinese adults. Arch Med Res 2008;39:232–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gallagher MM, Forleo GB, Behr ER, et al. Prevalence and significance of Brugada-type ECG in 12,012 apparently healthy European subjects. Int J Cardiol 2008;130:44–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gervacio-Domingo G, Isidro J, Tirona J, et al. The Brugada type 1 electrocardiographic pattern is common among Filipinos. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:1067–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tsuji H, Sato T, Morisaki K, et al. Prognosis of subjects with Brugada-type electrocardiogram in a population of middle-aged Japanese diagnosed during a health examination. Am J Cardiol 2008;102:584–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wajed A, Aslam Z, Abbas SF, et al. Frequency of Brugada-type ECG pattern (Brugada sign) in an apparently healthy young population. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2008;20:121–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Patel SS, Anees S, Ferrick KJ. Prevalence of a Brugada pattern electrocardiogram in an urban population in the United States. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2009;32:704–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Pecini R, Cedergreen P, Theilade S, et al. The prevalence and relevance of the Brugada-type electrocardiogram in the Danish general population: data from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Europace 2010;12:982–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Schukro C, Berger T, Stix G, et al. Regional prevalence and clinical benefit of implantable cardioverter defibrillators in Brugada syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2010;144:191–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Juang JM, Phan WL, Chen PC, et al. Brugada-type electrocardiogram in the Taiwanese population: is it a risk factor for sudden death? J Formos Med Assoc 2011;110:230–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Uhm JS, Hwang IU, Oh YS, et al. Prevalence of electrocardiographic findings suggestive of sudden cardiac death risk in 10,867 apparently healthy young Korean men. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011;34:717–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Juang JM, Chen CY, Chen YH, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of Brugada electrocardiogram patterns in an elderly Han Chinese population: a nation-wide community-based study (HALST cohort). Europace 2015;17(Suppl 2):ii54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Brugada R, Campuzano O, Sarquella-Brugada G, et al. Brugada syndrome. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J 2014;10:25–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, et al. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference. Heart Rhythm 2005;2:429–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Postema PG. About Brugada syndrome and its prevalence. Europace 2012;14:925–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Atarashi H, Ogawa S, Harumi K, et al. Characteristics of patients with right bundle branch block and ST-segment elevation in right precordial leads. Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation Investigators. Am J Cardiol 1996;78:581–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P. Right bundle-branch block and ST-segment elevation in leads V1 through V3: a marker for sudden death in patients without demonstrable structural heart disease. Circulation 1998;97:457–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Nademanee K, Veerakul G, Nimmannit S, et al. Arrhythmogenic marker for the sudden unexplained death syndrome in Thai men. Circulation 1997;96:2595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Priori SG, Napolitano C, Gasparini M, et al. Clinical and genetic heterogeneity of right bundle branch block and ST-segment elevation syndrome: a prospective evaluation of 52 families. Circulation 2000;102:2509–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]