Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to examine clinico-epidemiological properties of HIV/AIDS patients.

Materials and Methods:

For this purpose, 115 HIV/AIDS patients monitored in our clinic between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2013, were retrospectively evaluated.

Results:

For the 115 patients with a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS that we monitored, the mean age at the time of presentation was 34.5±13.21 (10–79) years. Eighty-nine (76.5%) patients were male and 27 (23.5%), female. In this study, HIV/AIDS was the most prevalent in the young male population with a low educational and sociocultural level. The most common mode of transmission in our patients was heterosexual relations: approximately 1 patient in 3 had a history of traveling to countries with a high prevalence of HIV/AIDS, namely, Russia and Ukraine. The examination of diagnosis with respect to years showed an increase in new cases since 2008. Only 21 (18.3%) of our patients were diagnosed through clinical symptoms, while 91 (81.7%) during routine scanning. At first presentation, 68% of our patients were stage A; 4.7%, stage B; and 27.3%, stage C. The mean length of the monitoring of our patients was 2.74 years (2–180 months). Thirteen (11.3%) patients died due to opportunistic infections and malignities. The most common opportunistic infection was tuberculosis (16.5%), followed by syphilis and HBV. Malignity, most commonly intracranial tumor, was seen in 8.6% patients.

Conclusion:

The disease was generally seen in the young male population with a low sociocultural level, and it was most frequently transmitted by heterosexual sexual contact. This clearly shows the importance of sufficient, accurate information, and education on the subject of the disease and its prevention. The fact that many of our patients were diagnosed in the late stage due to stigma and that diagnosis was largely made through scanning tests confirms the importance of these tests in early diagnosis.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, epidemics, screening tests, education

ÖZ

Amaç:

Bu çalışmanın amacı HIV/AIDS hastalarının klinik ve epidemiyolojik özelliklerinin irdelenmesidir.

Gereç ve Yöntem:

Bu amaçla 1 Ocak 1998 - 31 Aralık 2013 tarihleri arasında kliniğimizce takip edilen 115 HIV/AIDS tanılı hasta retrospektif olarak değerlendirildi.

Bulgular:

HIV/AIDS tanısıyla takip ettiğimiz 115 hastanın, başvuru anındaki ortalama yaşları 34,5±13,21 (10–79) olarak bulundu. Hastalarımızın 89 (%76,5)’u erkek, 27 (%23,5)’si kadındı. Çalışmamızda HIV/AIDS’in en fazla eğitim ve sosyokültürel düzeyi düşük olan genç erkek popülasyonunda görüldüğü tespit edildi. Hastalarımızda HIV/AIDS’in en sık bulaş yolu heteroseksüel cinsel temas olup, hastaların yaklaşık üçte birinde Rusya, Ukrayna gibi HIV/AIDS prevalansının yüksek olduğu ülkelere seyahat etme öyküsü vardı. Hastaların yıllara göre tanı alma oranları irdelendiğinde, 2008 yılından itibaren yeni vaka sayılarında artış olduğu görülmektedir. Hastalarımızın sadece 21 (%18,3)’ine klinik semptomlar ile tanı konulurken, 94 (%81,7)’üne rutin taramalar sırasında tanı konulmuştu. Hastalarımızın ilk gelişte %68’i evre A’da, %4,7’si evre B’de iken %27,3’ü evre C’de idi. Hastalarınmızın ortalama takip süreleri 2,74 yıl (2–180 ay) olup fırsatçı enfeksiyonlar ve maliniteler nedeni 13 (%11.3) hastamız hayatını kaybetmişti. En sık görülen fırsatçı enfeksiyon tüberküloz (%16.5) olup, sifiliz ve HBV bunu takip etmekteydi. Malinite %8.6 hastada görülürken, en sık intrakraniyal tümör görülmekteydi.

Sonuç:

Hastalığın çoğunlukla sosyo-kültürel düzeyi düşük olan genç yaş populasyonunda görüldüğü ve en sık bulaş yolunun heteroseksüel cinsel temas olduğu görülmüştür. Bu bize hastalık ve korunma yolları konusunda yeterli, doğru bilgilendirmenin ve eğitimin önemini açıkça göstermektedir. Stigma gibi nedenlerle birçok hastamızın geç evrede tanı alabiliyor olması ve hastalarımızda tanının çoğunlukla tarama testleriyle konulmuş olması, erken tanıda bu testlerin gerekliliğini telkin etmiştir.

Introduction

According to the global report by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) for 2014, 36.9 million people across the world were estimated to be living with AIDS in 2014: 2 million people were newly infected with HIV/AIDS and 1.2 million died from AIDS-related conditions. With new therapeutic options, there has been an increase in the expected quality of life and life expectancy. HIV/AIDS has made major progress toward treatable disease status, rather than being an inevitably fatal one. Turkey is one of the countries where the prevalence is low, although there has been a particularly significant increase in the number of new cases in the last 2 years according to the Ministry of Health figures: it is striking that almost half of these patients are under the age of 35 years [1–3].

The purpose of this study is to examine the epidemiological, clinical findings of cases monitored with a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS in our clinic over a 15-year period.

Materials and Methods

Local Ethics Committee approval was received for this study before starting the study. One-hundred fifteen patients monitored with a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS serologically confirmed using the Western Blot test and with anti-HIV positivity at the Karadeniz Technical University’s School of Medicine at the Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology Clinic between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2013, were enrolled in the study. Clinical staging was based on the U.S. Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) staging system as revised in 1997. Written informed consent was not received from the patients due to nature of the study. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze parametric variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to analyze non-parametric variables. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All the analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 13.01 software (SPSS, Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA). Measurement data were expressed as mean±standard deviation and descriptive data as numbers and percentages (%).

Results

The mean age at presentation of our patients monitored with a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS was 34.5±13.21 (10–79) years. The mean age of males at the time of diagnosis was 34.5±9.19 years, and the mean age of females at diagnosis was 43±1.41 years. A large majority of patients were in the 40–44-age group. Eighty-nine (76.5%) of our patients were male and 27 (23.5%), female. Patients’ age-gender distributions are shown in Figure 1. A large majority of our patients had low socioeconomic and education levels.

Figure 1.

Patients age–gender distributions.

The mean duration of the monitoring of our patients was 2.74 years (2–180 months), and 13 patients (11.3%) died due to opportunistic infections and malignities.

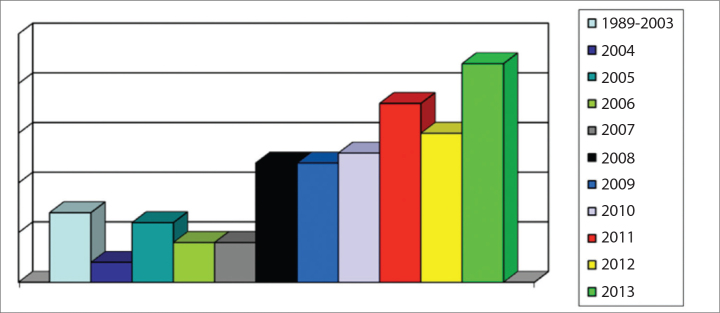

The levels of diagnosis by years are shown in Figure 2, which reveals a particular increase in the case numbers from 2008. One in 5 of our patients was diagnosed in 2013.

Figure 2.

Levels of diagnosis with regard to years.

Our patients’ demographic characteristics and probable routes of transmission are shown in Table 1. Most patients were married and had low levels of education. HIV/AIDS positivity was present in almost all the husbands of housewives. Thirty-three patients (28.7%) had a history of traveling abroad, most commonly to countries with a high prevalence of the disease, such as Russia, Georgia, and Ukraine. The most common route of transmission was through heterosexual relations.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients with HIV/AIDS and probable routes of transmission

| Marital status | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Married | 82 | 71.3 |

| Single | 15 | 13 |

| Widowed/divorced | 16 | 14 |

| Not known | 2 | 1.7 |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary school | 41 | 35.7 |

| High school | 29 | 25.2 |

| Middle school | 16 | 14 |

| No education/not known | 13 | 11.3 |

| University | 6 | 5.2 |

| Bachelors | 6 | 5.2 |

| Master’s | 3 | 2.6 |

| Doctorate | 1 | 0.8 |

| Occupational status | ||

| Housewife | 24 | 21 |

| Self-employed | 23 | 20 |

| Long-distance driver | 14 | 12 |

| Laborer | 14 | 12 |

| Unemployed | 10 | 9 |

| Not known | 10 | 9 |

| Retired | 8 | 7 |

| Student | 6 | 5 |

| Imam | 3 | 2.5 |

| Teacher | 3 | 2.5 |

| History of travel abroad | ||

| Absent | 82 | 71.3 |

| Georgia | 12 | 10.4 |

| Others* | 9 | 7.9 |

| Russian Federation | 8 | 7 |

| Ukraine | 4 | 3.4 |

| Probable mode of transmission | ||

| Heterosexual relations | 93 | 81 |

| Not known | 8 | 7 |

| Homosexual relations | 5 | 4.3 |

| Blood transfusion | 3 | 2.6 |

| During surgery | 3 | 2.6 |

| Maternal transmission | 2 | 1.7 |

| Intravenous drug use | 1 | 0.8 |

Others*: Romania, France, USA, Saudi Arabia, Austria, England, Greece

HIV/AIDS screening of individuals in close contact with patients, such as spouses, sexual partners, and children, revealed positivity in 35 (30.4%) and negativity in 52 (45.2%), while serology was unknown in 28 (24.3%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Serological status of individuals in close contact with patients

| Number (n=115) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | 52 | 45.2 |

| Positive | 35 | 30.4 |

| Not known | 28 | 24.3 |

Twenty-one (18.3) of our patients were diagnosed through clinical symptoms and 94 (81.7%) through routine screening. Forty-two (36.5%) of the 94 patients diagnosed through screening tests were screened at their own request, 30 (26.1%) due to HIV positivity in spouses or sexual partners, and 10 (8.7%) were identified through preoperative tests (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of patients diagnosed through screening tests.

Opportunistic infections, malignities, and prognoses in our patients are shown in Table 3. Opportunistic infections were the most common cause of mortality, tuberculosis being the most common. The most common malignity was intracranial malignities.

Table 3.

Opportunistic infections, malignities, and prognoses in our patients with HIV/AIDS

| n/% | |

|---|---|

| Opportunistic infections | |

| Tuberculosis | 19/16.5 |

| Shingles | 3/2.6 |

| PCP | 3/2.6 |

| Bacterial pneumonia | 3/2.6 |

| Lymphoma | 3/2.6 |

| Cryptosporidium-related diarrhea | 3/2.6 |

| Candidiasis | 3/2.6 |

| CMV disease | 3/2.6 |

| PML | 2/1.7 |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma | 2/1.7 |

| Cerebral toxoplasmosis | 1/0.9 |

| ITP | 1/0.9 |

| Malignities | |

| Intracranial | 3/2.6 |

| Pulmonary | 2/1.7 |

| Karposi’s sarcoma | 2/1.7 |

| Diffuse large B cell lymphoma | 1/0.9 |

| Burkitt’s lymphoma | 1/0.9 |

| Cervical dysplasia | 1/0.9 |

| Mortality | 13/11.3 |

CMV: cytomegalovirus; ITP: immune thrombocytopenia; PCP: Pneumocystis jirovecii (carinii) pneumonia; PML: progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

No data were available for 29 patients who failed to attend regular check-ups.

At first presentation, 68% patients were stage A; 4.7%, stage B; and 27.3%, stage C (Table 4).

Table 4.

Stages of the disease at initial presentation

| Number (n=103) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | 20 | 19.4 |

| A2 | 37 | 35.9 |

| A3 | 13 | 12.6 |

| Total | 70 | 68 |

| B1 | 0 | 0 |

| B2 | 3 | 2.9 |

| B3 | 2 | 1.9 |

| Total | 5 | 4.9 |

| C1 | 0 | 0 |

| C2 | 5 | 4.9 |

| C3 | 23 | 22.3 |

| Total | 28 | 27.2 |

Discussion

Sexually active young people aged 20–45 years are the most important risk group in terms of the transmission of HIV; the disease is generally diagnosed in more advanced periods because of clinical findings appearing in the later stages and patients presenting late to health institutions. According to the Turkish Ministry of Health figures, HIV/AIDS in Turkey is the most commonly diagnosed in men with ages of 40–49 years and in women with ages of 30–34 years. The age distribution varies considerably in different studies conducted in Turkey, and this has also been attributed to patients presenting in the late period [3–6]. The mean age of the patients in this study was 34.5±13.21 years, with a mean age of 34.5±9.19 years for men and 43±1.41 years for women. The disease can be diagnosed at younger ages in countries where the incidence of HIV/AIDS is high and also in many developed countries. This variation can be explained by higher levels of awareness of HIV/AIDS and widespread screening tests in these countries [7].

Males comprise a majority of HIV/AIDS patients in regions outside Sub-Saharan Africa [3]. Two-thirds of the patients in our study were male. According to the Ministry of Health figures for 2012, 71% of the reported cases in Turkey involved males and 29% were females. Similar levels appear in other studies from Turkey [4, 9]. The disease is more prevalent among males due to high-risk behavior in terms of transmission, such as contact with prostitutes and homosexuality.

According to the Ministry of Health figures, there has been an increase in the numbers of cases as of 2004, and the numbers are now in the thousands, which is the case particularly in the last 2 years [3]. There was an increase in the number of cases as of 2008 in our study, the highest number of cases being seen in 2013. This increase may be attributed to an increase in the number of individuals coming to Turkey from Eastern Europe, where the prevalence is high, for sex tourism, and partly due to an increased awareness of the disease.

In agreement with other studies from Turkey, the disease was more prevalent in individuals with a low average level of education [8, 10]. However, a thesis published in Turkey in 2013 reported that HIV/AIDS was the most prevalent among university students and attributed this to problems in the referral chain, with green card holders being unable to present directly [11]. One study intended to determine the levels of knowledge of HIV/AIDS among teachers in Sivas showed that even such individuals, who are expected to provide guidance to the community, were inadequately informed [12].

The most common route of the transmission of HIV/AIDS in Turkey, as elsewhere in the world, is through heterosexual relations [3]. Heterosexual relations with sex workers from Eastern European and Central Asian countries, where the incidence of HIV/AIDS is high, play a major role [3]. Patients with a history of working overseas or traveling abroad for other reasons also contribute toward the spread of HIV/AIDS [3]. The most common destinations among the 33 patients (28.7%) with a history of travel abroad in our study were Russia, Ukraine, and Georgia. The most common route of transmission in Turkey (80.9%) is through heterosexual relations. While the level of the disease is high in Turkey, the Ministry of Health reports that the route of transmission is unknown for approximately 1 in 3 cases. In addition, we think that because homosexual relations and intravenous drug use are regarded as taboo in the Turkish society, the reported levels of transmission may not reflect the actual situation.

A majority of our female patients were housewives. These have also represented a majority of subjects in other studies. This may be due to almost all the husbands of housewives being infected with HIV/AIDS. Other occupational groups observed in this study were self-employed long-distance drivers and laborers (especially those working overseas) [8–11]. In global terms, occupational distributions vary according to the sociocultural levels of the society concerned [10].

Upon examination of HIV serologies of individuals in close contact with our patients, such as spouses, sexual partners, and children, 45.2% were negative and 30.4% were positive, while the serology was unknown in 24.3% patients. Positivity levels are low in other studies from Turkey, while the number of cases in which the serology is unknown is quite high [13]. This may be attributed to patients frequently concealing their disease from those around them.

Testing in Turkey is only compulsory in the case of blood and organ donation, and 81.7% of our patients were diagnosed through screening tests. In one study from Turkey, Yemisen et al. [14] reported that as many as 62.6% out of 829 patients with HIV/AIDS were diagnosed through routine scanning tests. Although the routine use of screening tests for diagnostic purposes is costly, our study, like other previous studies, reveals the importance of these tests for Turkey [10, 15].

The association between malignity and HIV/AIDS has long been known. An increase in the prevalence has also been observed, not only of types of cancers indicative of AIDS, such as Kaposi’s sarcoma, NHL, and invasive cervical cancer, but also in other types of cancers [16–19]. Malignity was identified in 10 (8.6%) of our patients. The most common malignity was intracranial sarcoma, followed by pulmonary sarcoma, and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Varying malignities have been reported in other studies from Turkey [6, 9].

The most common opportunistic infection in our study was tuberculosis. The most common opportunistic infections in other studies from Turkey are reported as candidiasis, PCP, and tuberculosis [5, 6, 13, 15]. The incidence of tuberculosis was greater in this study than in other studies [15, 20]. This may be due to our patients’ presenting more in later periods and to patients started on isoniazid prophylaxis not receiving regular prophylaxis at appropriate doses or durations. The incidences of PCP and Candida infection were lower than expected in our study.

Despite improvements in monitoring and treatment options, HIV/AIDS patients still encounter significant problems in regular monitoring. Patients eventually begin failing to attend check-ups, for reasons such as social factors and stigma. The mean length of monitoring in our patients was 2.74 years (33 months). This is a fairly short period, given the patients’ mean ages. Similar findings have been reported in other studies from Turkey, and significant problems have been encountered in HIV/AIDS patients attending regular checks [14].

Despite all the advances in treatment, there are still around 1.5–2 million HIV/AIDS-related deaths every year. Thirteen (11.3%) of our patients died during monitoring. High mortality levels are more common in developing countries, where access to treatment is problematic, and late presentation to health institutions is one of the main reasons. Mortality levels vary in studies from Turkey, and they are particularly high in patients presenting late [13, 15]. The most common cause of death in studies from Turkey is tuberculosis, followed by other opportunistic infections [8, 9]. Eleven patients in this study died due to opportunistic infections, most commonly tuberculosis, followed by CMV infection. A significant decrease in mortality levels has been observed in studies performed since 2000, the most important reason being reported as improvements in and better access to treatment [6].

The main cause of mortality in patients who start treatment in the early period is an increase in malignities. The most common cause of mortality in one study was again described as malignities [11]. This was attributed to patients presenting in the early period and receiving regular treatment. Two of our patients died due to malignities. We were unable to establish why 29 (25.2%) of our patients failed to attend check-ups. We assume that although the morality levels in this study were low, the real number may have been higher.

In conclusion, despite all the progress made, HIV/AIDS is still a disease with no curative treatment, and also a significant cause of mortality. The simplest and most rational course is, therefore, to avoid the disease. The fact that the most common mode of infection was through sexual relations and that the disease was most common in the young male population with a low sociocultural level clearly shows the importance of sufficient, accurate information and education on the subject of the disease and its prevention. The fact that many of our patients were diagnosed in the late stage, due to stigma, and that diagnosis was largely made through scanning tests confirms the importance of these tests in early diagnosis.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from the ethics committee of Karadeniz Technical University, Farabi Hospital.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was not obtained from patients due to the nature of this study.

Author Contributions: Concept - S.K., I.K.; Design - S.K.,I.K.; Supervision- S.K., I.K.; Materials - B.E., S.K., I.K.; Data collection and/or Processing - B.E., S.K.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - B.E., S.K., I.K.; Literature Review - B.E., S.K.; Writing - B.E., S.K.; Critical Review - B.E., S.K., I.K.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosures: The authors declare that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2014.

- 2. UN Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS, Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic: 2012, November 2012.

- 3. Türkiye’de bildirilen HIV/AIDS vakalarının yıllara göre dağılımı (T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı) http://www.hatam.hacettepe.edu.tr/verilerAralik2012.pdf.

- 4.Mermut G, Avcı M, Tosun S. HIV/AIDS olguları: Onaltı yıllık izlem. 5.. Türkiye EKMUD kongresi;; 21–25 Mayıs 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taşdelen-Fışgın N, Tanyel E, Sarıkaya-Genç H, Tülek N. HIV/AIDS. The evaluation of HIV/AIDS cases. Klimik J. 2009;22:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alp E, Bozkurt I, Doganay M. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of HIV/AIDS patients followed-up in Cappadocia region: 18 years experience. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2011;45:125–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV surveillance report: Diagnoses of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, 2011. 2011;23 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/basic.htm#hivaidsage. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celikbas A, Ergonul O, Baykam N, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of HIV/AIDS patients in Turkey, where the prevalence is the lowest in the region. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2008;7:42–5. doi: 10.1177/1545109707306575. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545109707306575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Özgüneş N, Zengin-Elbir T, Yazıcı S, et al. Epidemiological and Clinical Evaluation of a Group of HIV/AIDS Patients Who Referred to Our Clinic. Flora The J Infect Dis Clin Microbiol. 2012;17:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karaosmanoglu HK, Aydin OA, Nazlican O. Profile of HIV/AIDS patients in a tertiary hospital in Istanbul, Turkey. HIV Clin Trials. 2011;12:104–8. doi: 10.1310/hct1202-104. https://doi.org/10.1310/hct1202-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Üstündağ SK. HIV Enfeksiyonlu Hastaların Retrospektif İrdelenmesi. İstanbul Üniversitesi Cerrahpaşa Tıp Fakültesi.; İstanbul.: 2013. Yayınlanmış doktora tezi. (Tez no:337764) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nur N. Turkish school teachers’ knowledge and attitudes toward HIV/AIDS. Croat Med J. 2012;53:271–7. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2012.53.271. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2012.53.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erbay A, Kayaaslan B, Akıncı E, et al. Evaluation of Epidemiological, Clinical and Laboratory Features of HIV/AIDS Cases. Flora The J Infect Dis Clin Microbiol. 2009;14:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yemisen M, Aydın OA, Gunduz A, Ozgunes N, Mete B, Ceylan B, et al. Epidemiological profile of naive HIV-1/AIDS patients in Istanbul: the largest case series from Turkey. Curr HIV Res. 2014;12:60–4. doi: 10.2174/1570162x12666140411111803. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570162X12666140411111803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaya S, Yılmaz G, Erensoy S, Arslan M, Köksal I. Retrospective analysis of 36 HIV/AIDS patients. Klimik J. 2011;24:11–6. https://doi.org/10.5152/kd.2011.03. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbaro G, Barbarini G. HIV infection and cancer in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:1121–6. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.17.5.1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, Virgo P, McNeel TS, Scoppa SM, et al. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980–2002. AIDS. 2006;20:1645. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238411.75324.59. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000238411.75324.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greard L, Galicier L, Maillard A, et al. Systemic non-Hodgkin lemphoma in HIV-infected patients with effective suppression of HIV replication: persistent occurence but improved survival. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:478. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200208150-00003. https://doi.org/10.1097/00126334-200208150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Gail MH, et al. Cancer burden in the HIV-infected population in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:753. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr076. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djr076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Punar M, Uzel S, Cemil EH, et al. HIV infection: An analysis of 44 cases. Klimik J. 2000;13:94–7. [Google Scholar]