Abstract

Objective

This study examines nurse‐related clinical nonlicensed personnel (CNLP) in U.S. hospitals between 2010 and 2014, including job categories, trends in staffing levels, and the possible relationship of substitution between this group of workers and registered nurses (RNs) and/or licensed practical nurses (LPNs).

Data Source

We used 5 years of data (2010–2014) from an operational database maintained by Premier, Inc. that tracks labor hours, hospital units, and facility characteristics.

Study Design

We assessed changes over time in the average number of total hours worked by RNs, LPNs, and CNLP, adjusted by total patient days. We then conducted linear regressions to estimate the relationships between nurse and CNLP staffing, controlling for patient acuity, volume, and hospital fixed effects.

Principal Findings

The overall use of CNLP and LPN hours per patient day declined from 2010 to 2014, while RN hours per patient day remained stable. We found no evidence of substitution between CNLP and nurses during the study period: Nurse‐related CNLP hours were positively associated with RN hours and not significantly related to LPN hours, holding other factors constant.

Conclusions

Findings point to the importance of examining where and why CNLP hours per patient day have declined and to understanding of the effects of these changes on outcomes.

Keywords: Health care workforce, unlicensed assistive personnel, nurse staffing, clinical nonlicensed personnel, substitution

Demand for medical services in the United States is expected to rise as a result of an aging population, expanded health insurance coverage, and new technologies. At the same time, hospitals are under pressure to control costs and improve safety and quality, all in the context of a potential shortfall of clinical professionals, such as physicians, nurses, and licensed allied professionals (Keenan 2010; Roehrig, Turner, and Hempstead 2015).

The use of the minimally trained, low‐wage clinical nonlicensed personnel (CNLP), who perform tasks under the supervision of registered nurses (RNs) or other licensed clinical providers, has been a primary strategy for hospitals to both manage professional shortages and reduce costs (Huston 1996; Zimmermann 2000). Research to date on this workforce has focused on a subset of CNLP called “unlicensed assistive personnel” (UAP), composed primarily of aides and orderlies who report directly to nurses (American Nurses Association 1997). The delegation of specific tasks to these nurse‐related support workers presumably allows nurses to focus on more complex situations (Huston 1996). Indeed, one previous study reported that nurses themselves perceive that UAP improve nursing efficiency in acute‐care settings (Jenkins and Joyner 2013).

Given the robust literature on the importance of nurse staffing to patient safety (Aiken, Clarke, and Sloane 2002; Aiken et al. 2010; Needleman et al. 2011), a significant yet largely unexplored question is how CNLP staffing levels and nurse staffing levels affect each other. Is it a relationship of complementarity, in which staffing of both groups rises and falls together in response to factors such as patient volume? Is it a relationship of substitution, in which the hiring of more CNLP allows hospitals to hire fewer nurses? Or is it some combination of the two, depending on management strategies and a hospital and region's context?

These questions are relevant to hospitals’ efforts to maximize labor efficiency, minimize nurse burnout and turnover, and, of course, protect and improve patient outcomes. They are also pertinent to the question of state laws regarding minimum nurse‐to‐patient ratios. With two states mandating ratios (California and Massachusetts1) and 14 other states requiring either staffing committees or public reporting of nurse staffing levels, the policy focus has been primarily on RNs, with little or no consideration of how CNLP staffing affects nurses’ workloads (Emergency Nurses Association 2014; ANA 2015).

The results of previous studies that examined the relationship between nurse staffing and support staffing were contradictory. Two studies on the hospital use of UAP found a positive correlation between hospital nurse staffing and UAP staffing, suggesting a relationship of complementarity. Harless and Mark (2010), using administrative data from California's Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, found simultaneous increases in the use of RNs (by 2 percent) and nursing aides and orderlies (by 12 percent) in California's hospitals between 1998 and 2001. Furukawa, Raghu, and Shao (2010) found similar trends, using data from the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators® between 2004 and 2008.

On the other hand, Potter et al. (2003) found a negative association between RN and patient care technicians, suggesting a possible substitution effect. More recent studies on the effects of California's nurse staffing law also found decreased use of nurse aides and orderlies associated with increased use of nurses in hospitals attempting to meet the minimum patient‐to‐nurse ratios (Donaldson et al. 2005; Bolton et al. 2007; Spetz et al. 2009; Donaldson and Shapiro 2011; Serratt et al. 2011; Cook et al. 2012).

This study builds on the existing literature to examine the relationship of RNs and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) to a larger group of support workers who we define as “nurse‐related CNLP.” This category includes five jobs traditionally identified as UAP, as well as three additional jobs that affect nurse workloads, for a total of eight nurse‐related CNLP job titles. Our study lays the methodological groundwork for future research that could examine the effect of different state laws on nurse staffing configurations and the effect of different staffing configurations on patient outcomes.

We focus on three research questions as follows:

What was the distribution of staffing (as measured in average total worked hours) for each of the eight nurse‐related CNLP jobs in hospitals in 2014?

How did RN, LPN, and CNLP staffing change from 2010 to 2014?

How did the variations in staffing for CNLP (both the subset of UAP and the full group of nurse‐related CNLP) correlate with RN and LPN staffing over the study period?

Methods

Data Source and Study Sample

We used a proprietary database owned by Premier, Inc.2 The dataset captures operational information on more than 500 of Premier's membership hospitals, including basic facility characteristics, department codes and descriptions, job titles and descriptions, and staffing information such as labor hours, expenses, and skill‐mix category. The dataset provides a unique opportunity to track the hospital‐based workforce and, in particular, to identify a variety of CNLP job titles across different hospital departments.

After excluding hospitals that did not have complete staffing records, our sample includes 523 hospitals over 5 years (January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2014). This sample covers health care systems in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. As shown in the Appendix, characteristics of hospitals in the sample are similar to those of community hospitals reported by other national hospital databases.3

Identification and Categorization of Nurse‐Related Clinical Nonlicensed Personnel

We began by reviewing all jobs in Premier's database classified as “clinical nonlicensed,” a category that in theory excludes jobs that require either a license or a baccalaureate degree. To better understand each job, we compared them to jobs listed in both the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Occupational Outlook Handbook (2015) and major online job boards that specify training requirements and job descriptions.

Using the requirements of delegation and supervision defined by the ANA (1997) and the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN 2005), we then selected eight “nurse‐related” CNLP jobs. The first five jobs constitute the ANA‐defined UAP category and are composed of nurse‐delegated jobs and nurse‐supervised jobs, as follows: nursing assistants, patient care technicians, transporters, graduate nurses, and surgical aides (American Nurses Association 1997). These five jobs are also consistent with the UAP classification in the nurse staffing measures endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF 2012). We included graduate nurses (newly graduated nurses who have not yet passed their licensure exam) because the NQF‐endorsed staffing measures include this job in the UAP group, and because Premier classifies it as a clinical nonlicensed job. However, we recognize that some states’ graduate nurses may include RNs who have been recently licensed but are still in a period of training.

To determine whether any additional support jobs should be included in our analysis, we reviewed all other CNLP jobs with a chief nursing officer from a Washington, D.C. hospital and with the ANA's director of nursing practice. Drawing on these experts’ opinion, we identified three additional nurse‐related CNLP jobs: medical assistants, monitor technicians, and surgery technicians. These workers are not necessarily supervised by nurses, but their absence can result in nurses having to do their work.

We also measured LPN and RN hours in the database. We did not include charge nurses and advance practice registered nurses.

Measurement

The unit of analysis in this study is job category in a hospital‐calendar year. We measured hospital use of nurse‐related CNLP by calculating the annual average number of total worked hours for each of the eight selected CNLP jobs. This labor hour measure is all‐inclusive and accounts for regular work, overtime, education, meetings, call back (excluding on‐call hours during which staff are not actually called in), and other worked hours. Compared with full‐time equivalent workers, this measure allows us to capture the impacts of absences from work, as well as overtime hours.

Statistical Analysis

We first examined the distribution of 2014 hospital average work hours for each of the eight nurse‐related CNLP jobs. We then performed t‐tests to assess the relative change in hospital average annual work hours per patient day for each job from 2010 to 2014.4 To compare the relative staffing of CNLP to nurses, we analyzed trends in the median CNLP‐RN and CNLP‐LPN hour ratios (i.e., number of CNLP hours divided by RN or by LPN hours) among hospitals.5

To further understand the dynamic relationship among CNLP, LPN, and RN staffing, we conducted linear regressions, where the dependent variable was the number of nurse‐related CNLP hours in a given hospital‐year and the independent variables were the number of nurse hours fully interacted with 5‐year dummies (2010–2014). The coefficient of each interaction term, therefore, indicates the relationship between nurse and CNLP staffing from year to year, with a positive coefficient implying a complementary relationship and a negative coefficient implying a substitutable relationship. We controlled for variation in patient acuity and volume using number of patient days adjusted for case‐mix index (CMI).6 This approach has been used in prior studies on this topic (Harless and Mark 2010; McHugh et al. 2011; Cook et al. 2012). We also included hospital fixed effects to control for time‐invariant unobservable differences between hospitals, and year fixed effects to account for national time trends in nurse‐related CNLP staffing level. We reported regression coefficients and clustered robust standard errors at the hospital level. The significance level was set at .1, .05, and .01, with two‐tailed tests. All database management and statistical analysis were performed in STATA (v. 13.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Distribution and Changes in Nurse‐Related CNLP, RN, LPN Hours, 2010–2014

We found that in 2014, hospitals on average used a total of 173,337 nurse‐related CNLP work hours (Table 1). UAP (the subgroup of five jobs) hours accounted for an average of 78 percent of total nurse‐related CNLP hours in 2014, with the largest share of hours from nursing assistants (46 percent) and patient care technicians (39 percent). The overall nurse‐related CNLP hours per patient day were 1.48 in 2014, which was a slight decrease of 3 percent from total hours in 2010. Within the CNLP group, it was the UAP jobs, and nursing assistants in particular, that experienced the greatest decrease in work hours per patient day (−14 percent, p‐value = .04). In contrast, there was a rise in hours per patient day over time among graduate nurses and medical assistants (75 and 34 percent, respectively), although the differences were not statistically significant due to small sample size.

Table 1.

Nurse‐Related CNLP, RN, and LPN Hours and Hours per Patient Day in U.S. Hospitals, 2010–2014

| Occupations | Average Work Hours, 2014 | Average Percent of Work Hours in Total Nurse‐Related CNLP Hours, 2014 | Average Work Hours per Patient Day, 2014 | % Change in Work Hours per Patient Day, 2010–14 | p‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All nurse‐related CNLP | 173,337 | 100% | 1.483 | −2.6% | .591 |

| UAP | 135,763 | 78.3% | 1.106 | −7.7% | .119 |

| Nursing assistant | 79,423 | 45.8% | 0.607 | −14.2% | .040 |

| Transporter | 19,688 | 11.4% | 0.118 | −12.1% | .165 |

| Graduate nurse | 7,903 | 4.6% | 0.084 | 75.4% | .133 |

| Patient care technician | 67,913 | 39.2% | 0.424 | −9.2% | .409 |

| Surgical aide | 15,156 | 8.7% | 0.100 | −23.0% | .194 |

| Other nurse‐related CNLP | 43,885 | 25.3% | 0.395 | 14.6% | .064 |

| Surgery technician | 26,098 | 15.1% | 0.234 | −2.6% | .723 |

| Medical assistant | 18,864 | 10.9% | 0.198 | 34.0% | .151 |

| Monitor technician | 14,724 | 8.5% | 0.126 | −10.9% | .382 |

| RN | 523,610 | – | 4.405 | 0.4% | .906 |

| LPN | 30,054 | – | 0.248 | −35.2% | <.01 |

Note: Average percent of job hours was obtained by calculating the percent of each job's hours in total nurse‐related CNLP hours at the hospital level and averaging across hospitals. Average work hours per patient day were obtained by calculating each job's work hours per patient day at the hospital level and averaging across hospitals. p‐value denotes the statistical significance of the t‐test with the null hypothesis that the hospital average work hours per patient day for a given job did not change between 2010 and 2014.

CNLP, clinical nonlicensed personnel; UAP, unlicensed assistive personnel.

In 2014, hospitals on average used 4.4 RN hours and 0.2 LPN hours per patient day. While RN hours remained stable, LPN hours dropped sharply by 35 percent (p‐value < .01) between 2010 and 2014. The LPN decline in hospitals has been well documented elsewhere (Furukawa, Raghu, and Shao 2010; Harless and Mark 2002; Lindrooth et al. 2006).

Annual Trends in Staff Hours and Ratios, 2010–2014

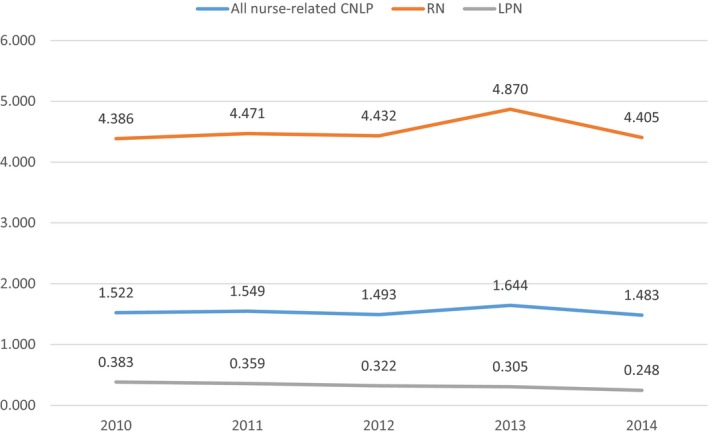

In examining the trends in nurse‐related CNLP and RN hours per patient day, we found some fluctuation, with a small decrease in 2012 followed by a recovery in hours in 2013 (Figure 1). Consistent with the literature on LPN use in hospitals previously cited, we found LPN hours per patient day decreased consistently during the study period.

Figure 1.

- Note: Staffing was measured as annual average work hours per case‐mix index‐adjusted patient day. CNLP, clinical nonlicensed personnel; LPN, licensed practical nurse; RN, registered nurse. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

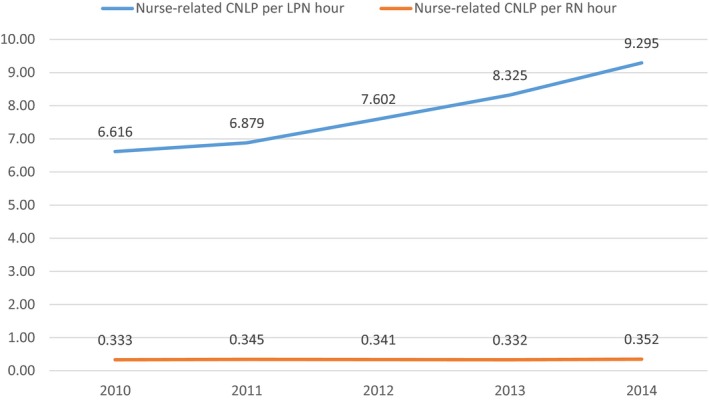

As shown in Figure 2, the median ratio of CNLP over RN hours increased slightly from 0.33 in 2010 to 0.35 in 2014, as a result of both average CNLP and RN hours holding relatively constant. On the other hand, as might be expected, there was an increase in the ratio of CNLP to LPN hours from 6.6 in 2010 to 9.3 in 2014, as a result of the continuous decrease in LPN staffing in hospitals. Overall, these ratio estimates are comparable to those reported in earlier studies (Furukawa et al. 2010; Cook et al. 2012).

Figure 2.

- Note: CNLP, clinical nonlicensed personnel; LPN, licensed practical nurse; RN, registered nurse. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Effects of RN and LPN Hours on CNLP Hours

Table 2 presents the estimated effects of RN hours and LPN hours on both UAP and CNLP (the full group of eight jobs) hours, while controlling for case‐mix adjusted patient volume, hospital fixed effects, and year fixed effects. For rescaling purposes, we divided the number of hours by 1,000. Results from the CNLP regression (column 1) suggest that RN hours were positively and significantly associated with variation in CNLP hours in each year, holding other factors constant. In 2010, one additional RN hour was associated with an increase of 0.27 CNLP hours. In 2014, the effect of one RN hour was almost the same (0.25 hours). A t‐test of RN hours in 2010 and 2014 shows that the magnitudes of the RN hour and year interactions were similar across 5‐year interactions, suggesting a stable complementary relationship between RN and CNLP staffing over the sample period. The results from the UAP regression (column 2) show that RN hours were also positively associated with UAP hours and that relationship remained stable across 5 years. The smaller magnitude of coefficients for UAP hours is consistent with the smaller annual hours for UAP than CNLP from the descriptive results.

Table 2.

Regression Analyses of the Relationship between RN and LPN Hours and Nurse‐Related CNLP Hours, 2010–2014

| Annual Hours | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| All Nurse‐Related CNLP | UAP | |

| Coefficients | Coefficients | |

| [SE] | [SE] | |

| RN Hours*Yeart | ||

| 2010 | 0.273*** | 0.230*** |

| [0.056] | [0.051] | |

| 2011 | 0.289*** | 0.248*** |

| [0.056] | [0.050] | |

| 2012 | 0.270*** | 0.233*** |

| [0.052] | [0.046] | |

| 2013 | 0.260*** | 0.223*** |

| [0.051] | [0.045] | |

| 2014 | 0.251*** | 0.212*** |

| [0.051] | [0.046] | |

| LPN Hours*Yeart | ||

| 2010 | 0.769* | 0.641 |

| [0.441] | [0.451] | |

| 2011 | 0.713 | 0.580 |

| [0.464] | [0.470] | |

| 2012 | 0.748 | 0.586 |

| [0.469] | [0.473] | |

| 2013 | 0.728 | 0.582 |

| [0.472] | [0.472] | |

| 2014 | 0.785 | 0.614 |

| [0.548] | [0.530] | |

| CMI‐adjusted patient days | 0.132* | 0.102 |

| [0.068] | [0.066] | |

| T‐test of β(RN Hour*Y2010) = β(RN Hour*Y2014) | ||

| t statistics | 1.319 | 0.845 |

| p‐value | .252 | .359 |

| T‐test of β(LPN Hour*Y2010) = β(LPN Hour*Y2014) | ||

| t statistics | 0.004 | 0.019 |

| p‐value | .947 | .890 |

| Observations | 1,135 | 1,126 |

| R‐squared | 0.968 | 0.962 |

Note: Average UAP, CNLP, RN, and LPN hours are rescaled by 1,000. Robust standard errors, clustered by hospital, are reported in brackets. Model was adjusted for hospital and year fixed effects to account for unobservable factors that may differ across hospitals and the national time trends in the UAP and nurse‐related CNLP staffing level.

*p < .1 **p < .05 ***p < .01.

CMI, case‐mix index; CNLP, clinical nonlicensed personnel; LPN, licensed practical nurse; RN, registered nurse; SE, standard error; UAP, unlicensed assistive personnel.

In contrast, the results suggest no statistical significant association between CNLP and LPN hours, holding other factors constant (except in 2010, when there was a marginally significant relationship). The same finding holds for the subgroup of UAP jobs.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is that, while the characteristics of the hospitals in the sample resemble those of the national sample (see Appendix), it is a convenience sample and thus may not be representative of all U.S. hospitals. Secondly, the small sample size may have affected the statistical power in our regression analysis, which in particular may have obscured a significant relationship of substitution of LPN to UAP. A third limitation is that the labor hour measure we used included not only regular work and overtime hours but also time spent on education, meetings, and callback. Although this provides a complete picture of hospital use of CNLP, it may influence the accuracy of measuring hours that CNLP workers spend on assisting clinical tasks (Spetz et al. 2009), and future research on this topic may need to exclude those hours. Lastly, our data did not allow us to control for other important time‐variant factors, such as hospital payer mix, and supply‐side factors such as the availability of CNLP and nurses and hospital competition in local areas.

Discussion

This study systematically examined national trends in hospital use of nurse‐related CNLP from 2010 to 2014 and analyzed their relationship to LPN and RN staffing levels. A first reflection is that the inclusion of five additional nurse support jobs, beyond the traditional five UAP jobs, appears to have been justified. While we found that UAP jobs are the majority of hours in this group (75 percent), our regression analysis shows that the relationship of RNs to “all nurse‐related CNLP” is strong. Thus, whereas past nurse staffing studies have considered only UAP, all eight of these jobs may be worth including in future research on RN staffing.

Our findings show stable trends in overall CNLP and RN hours, but a significant reduction in LPN and certain CNLP job hours per patient day between 2010 and 2014. The sharp decline nationally in LPN employment in hospitals is well known (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 1995, 2014a,b). On the other hand, the question of who is taking up their work remains unanswered. Further analysis is needed to examine specific CNLP jobs that may interact with the LPN staffing decline.

The notable drop in nursing assistant hours per patient day is a new finding and raises questions about who is substituting for them. Within the nurse‐related CNLP group, we found that graduate nurses’ and medical assistants’ hours increased, so it is possible that these groups are filling in. The increase in graduate nurses is likely a function of the dramatic increases in nurse graduation rates during this period (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2014), although it could also be related to complaints from newly graduated nurses that they were facing difficulties finding RN jobs during those years (Mancino 2013; Sellers 2013). With regard to medical assistants, given that hospitals provide more ambulatory services than in the past (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission 2016), the increase in MA staff could be a result of new jobs in outpatient hospital departments, in which case there may be a shift in need, rather than substitution within a specific setting. Overall, these fluctuations suggest that the skill mix of these support jobs is dynamic and that research is needed to examine substitution within the nurse‐related CNLP group at the hospital departmental level.

Our regression analyses show that RN staffing was positively associated with CNLP staffing in hospitals from 2010 to 2014, suggesting a relationship of complementarity. Overall the relationship of complementarity is good news; it does not appear from our study that there is major task shifting from RNs to CNLP or that RNs are being replaced by lesser‐trained workers. Substitution was a concern in the mid‐1990s, during the period of expansion of managed care (Huston 1996; Zimmermann 2000).

On the other hand, it is important to point out that our analysis does not account for increased workloads. It is possible that the decline in LPN hours, combined with the reduction in nurse‐related CNLP hours, could create additional work for nurses, the remaining CNLP staff, or for both. This could be concerning given the robust body of research demonstrating the association of RN workload with burnout, high turnover, and reduced patient safety (Aiken, Clarke, and Sloane 2002; Aiken et al. 2010).

Clearly, more work is needed to understand possible facility‐level fluctuations of these worker hours across the nation, as well as other possible differences among hospitals. Potential drivers that merit study include the effect of hospitals’ financial distress on substitution of CNLP for RNs, and the impact of states’ nurse staffing regulations on the relationship. Most important, research that assesses the effects of different skill‐mix arrangements on patient‐level outcomes is a critical next step.

The approach used in this study adds to a growing body of work that is examining workforce substitution among health care occupations (Auerbach et al. 2013; Green, Savin, and Lu 2013). Understanding how to measure substitution and how it affects outcomes is important for hospital managers, quality experts, and regulators. It is also relevant to the development of more complex models of workforce projections at the state and national levels. While in the past health workforce projections have focused primarily on a single licensed profession at a time, there is increasing recognition that analyses should examine the interaction among professions (Salsberg 2013). Including health care support staff in outcome research and workforce projection is a logical next step.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Appendix Table.

Appendix Table 1. Characteristics of Hospitals in the Premier Database Versus Other National Databases.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This study was funded by a collaborative agreement from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' National Center for Health Workforce Data Analysis, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Data for this study were provided by Premier, Inc.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimer: None.

Notes

In Massachusetts the ratio law is specific to intensive care units.

Premier collects clinical, financial, pharmacy, supply chain, and operational data from its member hospitals on a daily, biweekly, monthly, or quarterly basis.

The proportion of teaching hospitals and average occupancy rate in our dataset is comparable to the national average, although our sample has a slightly larger proportion of not‐for‐profit, urban, and system‐affiliated hospitals, and hospitals with more staffed beds and admissions, as compared to the national sample from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey and Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project data. See Appendix Table 1 in Appendix SA2 for details.

Average work hours per patient day were obtained by calculating each job's work hours per patient day at each hospital and averaging across hospitals. The lower and upper 2.5 percent of the values in the full sample were trimmed to prevent outliers in work hours and patient days from skewing the mean ratio.

Median ratios, instead of average ratios, were used to avoid potential bias due to the skewness of average ratio measure.

The CMI‐adjusted patient days was calculated as follows: CMI‐adjusted patient days = CMI * [Total Patient Days/(1 – Gross Outpatient Revenue/Gross Patient Revenue)].

References

- Aiken, L. H. , Clarke S. P., and Sloane D. M.. 2002. “Hospital Staffing, Organizational Support, and Quality of Care: Cross‐National Findings.” International Journal of Quality in Health Care 14 (1): 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L. H. , Sloane D. M., Cimiotti J. P., Clarke S. P., Flynn L., Seago J. A., Spetz J., and Smith H. L.. 2010. “Implications of the California Nurse Staffing Mandate for Other States.” Health Services Research 45 (4): 904–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association . 1997. Position Statement of Registered Nurse Utilization of UAP. Washington, DC: American Nurses Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association . 2015. “Nursing Staffing” [accessed on October 22, 2015]. Available at http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/Policy-Advocacy/State/Legislative-Agenda-Reports/State-StaffingPlansRatios

- Auerbach, D. I. , Chen P. G., Friedberg M. W., Reid R., Lau C., Buerhaus P. I., and Mehrotra A.. 2013. “Nurse‐Managed Health Centers and Patient‐Centered Medical Homes Could Mitigate Expected Primary Care Physician Shortage.” Health Affairs 32 (11): 1933–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, L. B. , Aydin C. E., Donaldson N., Brown D. S., Sandhu M., Fridman M., and Aronow H. U.. 2007. “Mandated Nurse Staffing Ratios in California: A Comparison of Staffing and Nursing‐Sensitive Outcomes Pre‐ and Post‐Regulation.” Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice 8 (4): 238–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, A. , Gaynor M. Jr, Stephens M., and Taylor L.. 2012. “The Effect of a Hospital Nurse Staffing Mandate on Patient Health Outcomes: Evidence from California's Minimum Staffing Regulation.” Journal of Health Economics 31 (2): 340–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, N. , and Shapiro S.. 2011. “Impact of California Mandated Acute Care Hospital Nurse Staffing Ratios: A Literature Synthesis.” Policy, Politics, and Nursing Practice 11 (3): 184–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, N. , Bolton L. B., Aydin C., Brown D., Elashoff J. D., and Sandhu M.. 2005. “Impact of California's Licensed Nurse‐Patient Ratios on Unit‐Level Nurse Staffing and Patient Outcomes.” Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice 6 (3): 198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emergency Nurses Association . 2014. “50 State Nurse Safe Staffing Laws” [accessed on October 22, 2015]. Available at https://www.ena.org/government/State/Documents/SafeNurseStaffingLaws.pdf

- Furukawa, M. F. , Raghu T. S., and Shao B. B.. 2010. “Electronic Medical Records, Nurse Staffing, and Nurse‐Sensitive Patient Outcomes: Evidence from the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators.” Medical Care Research and Review 68 (3): 311–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, L. V. , Savin S., and Lu Y.. 2013. “Primary Care Physician Shortages Could Be Eliminated through Use of Teams, Nonphysicians, and Electronic Communication.” Health Affairs 32 (1): 11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harless, D. W. , and Mark B. A.. 2010. “Nurse Staffing and Quality of Care with Direct Measurement of Inpatient Staffing.” Medical Care 48 (7): 659–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston, C. L. 1996. “Unlicensed Assistive Personnel: A Solution to Dwindling Health Care Resources or the Precursor to the Apocalypse of Registered Nursing?” Nursing Outlook 44 (2): 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, B. , and Joyner J.. 2013. “Preparation, Roles, and Perceived Effectiveness of Unlicensed Assistive Personnel.” Journal of Nursing Regulation 4 (3): 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, P. 2010. “The Nursing Workforce Shortage: Causes, Consequences, Proposed Solutions” (#619). New York: Commonwealth Fund; [accessed on October 22, 2015]. Available at http://www.commonwealthfund.org/usr_doc/keenan_nursing.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindrooth, R. C. , Bazzoli G. J., Needleman J., and Hasnain‐Wynia R.. 2006. “The Effect of Changes in Hospital Reimbursement on Nurse Staffing Decisions at Safety Net and Nonsafety Net Hospitals.” Health Services Research 41 (3p1): 701–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancino, D. J. 2013. “Recalculating: The ‘Nursing Shortage’ Needs New Direction.” Dean's Notes 34 (3): 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M. D. , Kelly L. A., Sloane D. M., and Aiken L. H.. 2011. “Contradicting Fears, California's Nurse‐to‐Patient Mandate Did Not Reduce the Skill Level of the Nursing Workforce in Hospitals.” Health Affairs 30 (7): 1299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission . 2016. Hospital Inpatient and Outpatient Services: Assessing Payment Adequacy and Updating Payments, Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. [Google Scholar]

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing . 2005. “Working with Others: A Position Paper” [accessed on October 22, 2015]. Available at https://www.ncsbn.org/Working_with_Others.pdf

- National Quality Forum . 2012. “Nursing Hours per Patient Day.” [accessed on November 2, 2016]. Available at http://www.qualityforum.org/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?LinkIdentifier=id&ItemID=70962

- Needleman, J. , Buerhaus P., Pankratz V. S., Leibson C. L., Stevens S. R., and Harris M.. 2011. “Nurse Staffing and Inpatient Hospital Mortality.” New England Journal of Medicine 364 (11): 1037–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter, P. , Barr N., McSweeney M., and Sledge J.. 2003. “Identifying Nurse Staffing and Patient Outcome Relationships: A Guide for Change in Care Delivery.” Nursing Economics 21 (4): 158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehrig, C. , Turner A., and Hempstead K.. 2015. “Expanded Coverage Appears To Explain Much of the Recent Increase in Health Job Growth” [accessed on October 22, 2015]. Available at http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/11/20/expanded-coverage-appears-to-explain-much-of-the-recent-increase-in-health-job-growth/

- Salsberg, E. 2013. “Projecting Future Clinician Supply and Demand: Advances and Challenges. Presentation to National Health Policy Forum.” Washington, D.C. [accessed on October 1, 2016]. Available at http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/supplydemand/supplyanddemand.pdf

- Sellers, A. 2013. “Nurses Without Jobs: A Sign of the Times” [accessed on July 28, 2016]. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Health News. Available at http://www.georgiahealthnews.com/2013/05/nurses-jobs-sign-times/

- Serratt, T. , Harrington C., Spetz J., and Blegen M.. 2011. “Staffing Changes before and after Mandated Nurse‐to‐Patient Ratios in California's Hospitals.” Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice 12 (3): 133–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spetz, J. , Chapman S., Herrera C., Kaiser J., Seago J. A., and Dower C.. 2009. “Assessing the Impact of California's Nurse Staffing Ratios on Hospitals and Patient Care” [accessed on June 20, 2016]. Available at http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/PDF%20A/PDF%20AssessingCANurseStaffingRatios.pdf

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics . 1995. “Occupational Employment Statistics” [accessed on July 28, 2016]. Available at http://www.bls.gov/oes/

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics . 2014a. “Occupational Employment Statistics” [accessed on July 28, 2016]. Available at http://www.bls.gov/oes/

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics . 2014b. “Occupational Outlook Handbook Healthcare Occupations” [accessed on October 22, 2015]. Available at http://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/home.htm

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . 2014. “The Future of the Nursing Workforce: National‐ and State‐Level Projections, 2012–2025” [accessed on June 22, 2016]. Available at http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/supplydemand/nursing/workforceprojections/nursingprojections.pdf

- Zimmermann, P. G. 2000. “The use of Unlicensed Assistive Personnel: An Update and Skeptical Look at a Role That May Present More Problems Than Solutions.” Journal of Emergency Nursing 26 (4): 312–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Appendix Table.

Appendix Table 1. Characteristics of Hospitals in the Premier Database Versus Other National Databases.