Abstract

Objective

Inform health planning and policy discussions by describing Health Resources and Services Administration's (HRSA's) Health Workforce Simulation Model (HWSM) and examining the HWSM's 2025 supply and demand projections for primary care physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs).

Data Sources

HRSA's recently published projections for primary care providers derive from an integrated microsimulation model that estimates health workforce supply and demand at national, regional, and state levels.

Principal Findings

Thirty‐seven states are projected to have shortages of primary care physicians in 2025, and nine states are projected to have shortages of both primary care physicians and PAs. While no state is projected to have a 2025 shortage of primary care NPs, many states are expected to have only a small surplus.

Conclusions

Primary care physician shortages are projected for all parts of the United States, while primary care PA shortages are generally confined to Midwestern and Southern states. No state is projected to have shortages of all three provider types. Projected shortages must be considered in the context of baseline assumptions regarding current supply, demand, provider‐service ratios, and other factors. Still, these findings suggest geographies with possible primary care workforce shortages in 2025 and offer opportunities for targeting efforts to enhance workforce flexibility.

Keywords: Primary care, scope of practice, health workforce, shortage, training

Essential to successful health planning and policy is a solid understanding of future health workforce supply and demand (Ono, Lafortune, and Schoenstein 2013; GAO 2015). Both federal and nonfederal entities use workforce forecasts to guide their health education, training, and care delivery programs. In support of program planning within the Department of Health and Human Services and across the broader health community, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) periodically releases supply and demand projections for multiple health occupations. These projections inform policy at all levels and help ensure adequate provider supplies, particularly in underserved communities. Workforce projections also serve as critical planning tools for state and regional entities; health professions schools and educators; public health organizations; and professional organizations.

The HRSA recently released national and state‐level projections of primary care provider supply and demand in 2025, with 2013 data as baseline. These estimates derive from the Health Workforce Simulation Model (HWSM; HHS/HRSA 2016a, b), an integrated microsimulation model that forecasts supply and demand for multiple professions in various settings. The HRSA's HWSM affords insight into the dynamics of provider supply and demand, and represents an important step in improving health workforce forecasts.

To promote discussion and review of the HWSM, we offer this Perspectives article. Our aim is twofold: First, we provide insight into the HWSM, briefly describing its methodology, key assumptions, strengths, and limitations. Second, we use the HWSM's primary care projections to illustrate the model's output and explore implications for health workforce flexibility related to the geography of provider supply and demand.

Health Workforce Simulation Model Overview

The HSRA's HWSM relies on an individual‐level microsimulation methodology, rather than the cohort‐based approach previously used by the HRSA and others (HHS/HRSA 2016a). Microsimulation offers a more granular framework for assessing health provider supply and demand and can better support future analyses of alternative health care delivery and utilization scenarios as more comprehensive data become available.

The following text briefly outlines the HWSM's approach for estimating provider supply and demand, as well as the model's strengths and limitations. Details of the HWSM are available in the technical documentation posted on HRSA's website (HHS/HRSA 2014a; http://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/projections/simulationmodeldocumentation.pdf).

Provider Supply

The HWSM estimates the baseline supply for each modeled health occupation separately, using person‐level data to characterize providers’ age, sex, education, training, and geographic location. Where available, these microdata reflect information compiled from national registries. For professions without detailed registries, data from the American Community Survey (ACS) are used, with individual records replicated based on their sample weights, to yield comprehensive, provider‐specific baseline datasets. These individual‐level datasets also incorporate state‐level economic factors, including unemployment rates and average profession‐specific wages. State‐level estimates at baseline reflect each provider's practice location, while regional and national estimates reflect aggregated counts summed across applicable states.

New entrants to each year's workforce, as well as annual workforce attrition due to retirement, mortality, and career change, are simulated for each successive year beyond baseline using current patterns of training, retirement, and mortality. Thus, for a specific provider type, the workforce supply in a given year is equal to the previous year's supply plus the number of new entrants expected for that year minus the number of providers lost due to career change, retirement, and mortality. Ordinary least‐squares regression is then used to estimate the number of hours each provider works each week over the course of the year. For each provider type, the projected annual supply is reported as full‐time equivalents, calculated as the total estimated hours worked divided by the average number of hours worked per week.

Provider Demand

Estimates for health care demand similarly begin with individual‐level data. First, population characteristics, including demographic and socioeconomic information, are obtained from ACS and other data compiled by the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. states. This information is linked to health status and risk factor data from the Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and to health care utilization and insurance information collected through surveys, including the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (overseen by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).

Regression models are then used to estimate each person's health care utilization at baseline based on their demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, health and insurance status, and health risk factors. These estimates reflect both delivery setting and provider type/specialty.

Finally, staffing ratios specific to each delivery setting, provider type, and utilization measure (e.g., office visits, procedures, hospitalizations) are derived, assuming that current provider supply is sufficient to meet current demand, with adjustment for identified provider shortages (Ono, Lafortune, and Schoenstein 2013). For example, baseline demand for primary care physicians is assumed to be equal to baseline supply plus the approximately 8,200 physicians needed to address HRSA's Primary Care Health Provider Shortage Areas (HPSAs; HHS/HRSA 2014b). The derived staffing ratios are assumed to remain constant over the projection period.

Demand in each year after baseline is estimated by “aging” the population forward 1 year and using Census Bureau projections to account for population growth, migration, aging, and mortality. The baseline staffing ratios are then applied to each successive year's population to estimate total annual demand by delivery setting and provider type. Demand estimates are calculated at the national level and then pro‐rated to state levels based on each state's projected population characteristics (i.e., age, sex, socioeconomic characteristics, health status, insurance status, health risk factors).

HWSM Strengths and Limitations

Important strengths of the HWSM include application of a consistent approach to analyzing supply and demand across practitioner type and medical discipline; use of microsimulation methodologies to ensure representativeness and provide reliable population‐level estimates; and the capability to simultaneously examine the impact of multiple health care drivers, including population growth, changing demographics, health status, and expanded health insurance coverage.

A major limitation of the HWSM lies in its assumption of baseline equivalence. While consistent with other recent health workforce projection models (Ono, Lafortune, and Schoenstein 2013), HRSA recognizes that this assumption does not address local workforce imbalances. This limitation also impacts the interpretation of projected shortages and surpluses, as discussed later in this article.

Other limitations include the use of current levels of provider education, training, and attrition to estimate out‐year supplies, and the use of baseline staffing ratios to estimate out‐year demands. HRSA anticipates that future versions of the HWSM will allow more nuanced modeling of these factors.

Finally, HRSA recognizes that the current model produces only point estimates, rather than ranges, for supply and demand. While this is similar to other workforce projections, HRSA is continuing to build new capabilities into the HWSM to expand its scenario modeling capabilities and produce ranges of supply and demand.

Primary Care

The Institute of Medicine (IOM 1996) defines primary care as follows:

[T]he provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community.

In reiterating this definition, IOM emphasized several key aspects of primary care: It focuses on the person, not the illness; it serves as an initial resource when an individual seeks health care; and it is coordinated and comprehensive (Starfield and Horder 2007; IOM 2012). A report from the Agency for Health Research and Quality (Totten et al. 2016) expanded on these strengths, noting that primary care is amply sufficient to address a broad range of conditions, illnesses, and injuries, and that, even with serious conditions or diseases, primary care practitioners link an individual's health care utilization across settings and providers (Wilson et al. 2005). Moreover, by providing a usual source of care, primary care practitioners help individuals to foster ongoing provider relationships and to incorporate preventive services into their care plans. Specifically, primary care access is associated with lower rates of hospital readmission (Herrin et al. 2014; HRET 2015; McHugh et al. 2016). Higher numbers of general practitioners per capita are also associated with decreased hospital readmission rates (Herrin et al. 2014). Significant reductions in emergency department visits have been reported among individuals with chronic physical and/or behavioral health conditions who had more than two visits to a primary care clinic (Kim, Mortensen, and Eldridge 2015). Similarly, a California study of previously uninsured adults found that a policy targeting greater use of primary care providers and greater continuity of care resulted in decreased numbers of emergency department visits (Pourat et al. 2015). Collectively, these findings underscore the need to ensure adequate supplies of primary care providers across the United States.

While millions of Americans may now have financial access to primary care through insurance coverage, many still do not have physical access to care, even in areas where provider supplies may appear adequate. For example, Huang and Finegold estimated that 7 million people may lack access to health providers in areas where increased demand under the Affordable Care Act is greater than 10 percent of baseline supply (Huang and Finegold 2013). Sharzer et al. estimated that 16 percent of adults have difficulty accessing care. Among adults reporting access problems, 30 percent could not find a doctor who would see them (Sharzer, Long, and Anderson 2016), suggesting that in many areas, narrow provider networks may limit access to health care (Jost 2016).

Primary care providers include physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs) who practice in general and family medicine, general internal medicine, geriatrics, and general pediatrics (National Library of Medicine/MedLine Plus 2016).1 The Association of American Medical Colleges estimates that approximately 30 percent of the physicians practicing in 2014 were primary care physicians (IHS Inc 2016), while nearly 40 percent of PAs practice in primary care (NCCPA 2016). In contrast, approximately 80 percent of NPs are prepared in family care, adult care, geriatric care, or pediatric care (AANP 2015a, b).

Although academic and clinical training requirements vary across professions, all three professions undergo examination and certification at the national level and licensure at the state level. Like physicians, NPs and PAs may take medical histories, conduct exams, diagnose and treat illnesses, order and interpret tests, develop treatment plans, and provide preventive care. While some restrictions exist regarding the type of medication, NPs and PAs may prescribe medication in all 50 states and the District of Columbia (AANP 2015a, b; AAPA 2016).

Nurse practitioners and PAs do not replace physicians completely, but they can serve important roles as independent providers and as primary care team members. Indeed, substantial research evidence shows that primary care quality, including reduced hospitalization and emergency room visits, patient safety, and patient satisfaction, are comparable between patients served by NPs and PAs and those served by physicians (Mundinger et al. 2000; Horrocks, Anderson, and Salisbury 2002; Grumbach et al. 2003; Wilson et al. 2005; Laurant et al. 2009, 2005; Naylor and Kurtzman 2010; Hooker and Muchow 2015; Perloff, DesRoches, and Buerhaus 2016).

Recognizing that a well‐trained, well‐distributed primary care workforce is vital for America's health, considerable effort has focused on examining the distribution of primary care physicians, but less research has focused on NPs and PAs. Yet, because physicians, NPs, and PAs together form the bulwark of the primary care system, it is essential to take a holistic look at provider projections across occupations to obtain a clear picture of workforce adequacy and understand the collective geographic distribution of primary care practitioners.

This analysis offers a much needed window into primary care by examining the national, regional, and state distributions of primary care physicians, NPs, and PAs. These analyses speak to the importance of ongoing, rigorous work in developing projection models that consider entire sectors, rather than individual professions (Grover, Orlowski, and Erikson 2016). A comprehensive understanding of provider geography is also integral to health workforce planning (Dummer 2008) that supports effective deployment of the health workforce and overcomes geographic disparities in access to care.

Approach

Our analyses utilize HRSA's 2013 baseline estimates and 2025 projections of supply and demand for primary care physicians, NPs, and PAs. We examined supply and demand across provider type to give a comprehensive picture of how regional and state‐level distributions of each profession may influence the adequacy of the U.S. primary care provider workforce between 2013 and 2025.

Results

National Findings

In 2013, the supply of primary care physicians2 in the United States is estimated to be 216,580 FTEs, while demand is estimated to be 224,780 FTEs (Table 1). This difference between supply and demand reflects the approximately 8,200 primary care physicians needed to de‐designate HRSA's primary care HPSAs. Primary care physician adequacy, measured as the difference between supply and demand as a proportion of demand, is estimated to be −4 percent of 2013 demand. The estimated 2013 supplies of primary care NPs and PAs are 57,330 FTEs and 33,390 FTEs, respectively. Demands for these providers equal 2013 supplies, reflecting the assumption of baseline equivalence for NPs and PAs.

Table 1.

Primary Care Provider Supply and Demand, 2013

| Physicians | Nurse Practitioners (NPs) | Physician Assistants (PAs) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supply (S ) | Demand (D) | S –D | Adequacy (%) | Supply (S) | Demand (D) | S –D | Adequacy (%) | Supply (S) | Demand (D) | S –D | Adequacy (%) | |

| United States | 216,580 | 224,780 | −8,200 | −4 | 57,330 | 57,330 | 0 | – | 33,390 | 33,390 | 0 | – |

| Northeast | 43,720 | 41,600 | 2,120 | 5 | 10,950 | 10,640 | 310 | 3 | 6,300 | 6,100 | 200 | 3 |

| New England | ||||||||||||

| Connecticut | 2,690 | 2,710 | −20 | −1 | 980 | 690 | 290 | 42 | 420 | 400 | 20 | 5 |

| Maine | 1,320 | 990 | 330 | 33 | 510 | 250 | 260 | 104 | 240 | 150 | 90 | 60 |

| Massachusetts | 6,420 | 5,190 | 1,230 | 24 | 2,280 | 1,330 | 950 | 71 | 580 | 770 | −190 | −25 |

| New Hampshire | 1,110 | 950 | 160 | 17 | 460 | 240 | 220 | 92 | 180 | 140 | 40 | 29 |

| Rhode Island | 870 | 800 | 70 | 9 | 170 | 200 | −30 | −15 | 80 | 120 | −40 | −33 |

| Vermont | 630 | 450 | 180 | 40 | 220 | 120 | 100 | 83 | 100 | 70 | 30 | 43 |

| Middle Atlantic | ||||||||||||

| New Jersey | 6,050 | 6,590 | −540 | −8 | 1,020 | 1,690 | −670 | −40 | 340 | 980 | −640 | −65 |

| New York | 15,160 | 14,200 | 960 | 7 | 3,210 | 3,630 | −420 | −12 | 2,580 | 2,110 | 470 | 22 |

| Pennsylvania | 9,480 | 9,740 | −260 | −3 | 2,100 | 2,490 | −390 | −16 | 1,790 | 1,450 | 340 | 23 |

| Midwest | 48,230 | 49,270 | −1,040 | −2 | 11,700 | 12,560 | −860 | −7 | 6,500 | 7,380 | −880 | −12 |

| East North Central | ||||||||||||

| Illinois | 9,440 | 9,190 | 250 | 3 | 1,700 | 2,340 | −640 | −27 | 880 | 1,370 | −490 | −36 |

| Indiana | 4,040 | 4,810 | −770 | −16 | 1,380 | 1,220 | 160 | 13 | 230 | 710 | −480 | −68 |

| Michigan | 7,140 | 7,480 | −340 | −5 | 1,240 | 1,910 | −670 | −35 | 1,360 | 1,110 | 250 | 23 |

| Ohio | 8,170 | 8,660 | −490 | −6 | 1,960 | 2,210 | −250 | −11 | 450 | 1,290 | −840 | −65 |

| Wisconsin | 4,340 | 4,120 | 220 | 5 | 1,170 | 1,050 | 120 | 11 | 640 | 610 | 30 | 5 |

| West North Central | ||||||||||||

| Iowa | 2,140 | 2,240 | −100 | −4 | 420 | 570 | −150 | −26 | 490 | 330 | 160 | 48 |

| Kansas | 1,970 | 2,090 | −120 | −6 | 730 | 530 | 200 | 38 | 500 | 310 | 190 | 61 |

| Minnesota | 4,580 | 3,850 | 730 | 19 | 1,090 | 980 | 110 | 11 | 820 | 570 | 250 | 44 |

| Missouri | 3,950 | 4,480 | −530 | −12 | 1,270 | 1,140 | 130 | 11 | 220 | 660 | −440 | −67 |

| Nebraska | 1,310 | 1,280 | 30 | 2 | 300 | 320 | −20 | −6 | 480 | 190 | 290 | 153 |

| North Dakota | 530 | 490 | 40 | 8 | 250 | 120 | 130 | 108 | 160 | 70 | 90 | 129 |

| South Dakota | 610 | 590 | 20 | 3 | 180 | 150 | 30 | 20 | 280 | 90 | 190 | 211 |

| South | 73,570 | 83,010 | −9,440 | −11 | 22,490 | 21,160 | 1,330 | 6 | 11,710 | 12,400 | −690 | −6 |

| South Atlantic | ||||||||||||

| Delaware | 670 | 680 | −10 | −1 | 160 | 170 | −10 | −6 | 90 | 100 | −10 | −10 |

| District of Columbia | 1,090 | 420 | 670 | 160 | 230 | 110 | 120 | 109 | 100 | 60 | 40 | 67 |

| Florida | 12,250 | 14,160 | −1,910 | −13 | 3,670 | 3,610 | 60 | 2 | 1,680 | 2,110 | −430 | −20 |

| Georgia | 5,930 | 6,690 | −760 | −11 | 1,570 | 1,700 | −130 | −8 | 950 | 990 | −40 | −4 |

| Maryland | 4,810 | 4,280 | 530 | 12 | 860 | 1,100 | −240 | −22 | 540 | 640 | −100 | −16 |

| North Carolina | 6,480 | 6,960 | −480 | −7 | 1,610 | 1,770 | −160 | −9 | 1,900 | 1,030 | 870 | 84 |

| South Carolina | 2,910 | 3,340 | −430 | −13 | 870 | 850 | 20 | 2 | 360 | 500 | −140 | −28 |

| Virginia | 5,670 | 5,800 | −130 | −2 | 1,980 | 1,480 | 500 | 34 | 700 | 860 | −160 | −19 |

| West Virginia | 1,340 | 1,480 | −140 | −9 | 340 | 380 | −40 | −11 | 390 | 220 | 170 | 77 |

| East South Central | ||||||||||||

| Alabama | 2,720 | 3,540 | −820 | −23 | 770 | 900 | −130 | −14 | 130 | 530 | −400 | −75 |

| Kentucky | 2,660 | 3,330 | −670 | −20 | 930 | 850 | 80 | 9 | 480 | 490 | −10 | −2 |

| Mississippi | 1,470 | 2,010 | −540 | −27 | 1,080 | 510 | 570 | 112 | 30 | 300 | −270 | −90 |

| Tennessee | 4,220 | 4,780 | −560 | −12 | 2,310 | 1,220 | 1,090 | 89 | 520 | 710 | −190 | −27 |

| East South Central | ||||||||||||

| Arkansas | 1,810 | 2,160 | −350 | −16 | 610 | 550 | 60 | 11 | 110 | 320 | −210 | −66 |

| Louisiana | 2,770 | 3,220 | −450 | −14 | 730 | 820 | −90 | −11 | 240 | 480 | −240 | −50 |

| Oklahoma | 2,290 | 2,830 | −540 | −19 | 560 | 720 | −160 | −22 | 530 | 420 | 110 | 26 |

| Texas | 14,490 | 17,330 | −2,840 | −16 | 4,220 | 4,400 | −180 | −4 | 2,960 | 2,560 | 400 | 16 |

| West | 51,080 | 50,880 | 200 | <1 | 12,190 | 12,970 | −780 | −6 | 8,870 | 7,500 | 1,370 | 18 |

| Mountain | ||||||||||||

| Arizona | 4,030 | 4,740 | −710 | −15 | 1,300 | 1,210 | 90 | 7 | 850 | 700 | 150 | 21 |

| Colorado | 3,950 | 3,510 | 440 | 13 | 1,100 | 890 | 210 | 24 | 1,290 | 520 | 770 | 148 |

| Idaho | 960 | 1,110 | −150 | −14 | 240 | 280 | −40 | −14 | 380 | 160 | 220 | 138 |

| Montana | 700 | 690 | 10 | 1 | 320 | 170 | 150 | 88 | 220 | 100 | 120 | 120 |

| Nevada | 1,460 | 1,850 | −390 | −21 | 320 | 470 | −150 | −32 | 240 | 270 | −30 | −11 |

| New Mexico | 1,440 | 1,400 | 40 | 3 | 530 | 350 | 180 | 51 | 320 | 210 | 110 | 52 |

| Utah | 1,520 | 1,970 | −450 | −23 | 410 | 500 | −90 | −18 | 360 | 290 | 70 | 24 |

| Wyoming | 350 | 390 | −40 | −10 | 160 | 100 | 60 | 60 | 140 | 60 | 80 | 133 |

| Pacific | ||||||||||||

| Alaska | 600 | 470 | 130 | 28 | 330 | 120 | 210 | 175 | 340 | 70 | 270 | 386 |

| California | 26,120 | 25,900 | 220 | 1 | 4,700 | 6,600 | −1,900 | −29 | 3,120 | 3,870 | −750 | −19 |

| Hawaii | 1,140 | 960 | 180 | 19 | 230 | 250 | −20 | −8 | 120 | 140 | −20 | −14 |

| Oregon | 3,350 | 2,900 | 450 | 16 | 920 | 740 | 180 | 24 | 520 | 430 | 90 | 21 |

| Washington | 5,430 | 5,020 | 410 | 8 | 1,630 | 1,280 | 350 | 27 | 960 | 750 | 210 | 28 |

U.S. Census Bureau Regions are shown in bold and Divisions are italicized (http://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf).

Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

Adequacy = 100 * [projected 2013 supply (S) − projected 2013 demand (D)]/[projected 2013 demand (D)].

Projections reflect baseline assumptions regarding supply, demand, new entrants into each profession, retirement patterns, and provider‐utilization ratios.

By 2025, the supply of primary care physicians is estimated to be 239,460 FTEs, while the demand is estimated to rise to 263,100 FTE, resulting in a shortage of 23,640 FTE primary care physicians (−9 percent of 2025 demand; Table 2). In contrast, both primary care NPs and PAs are expected to have national surpluses in 2025. The 2025 supply of primary care NPs is estimated to be 110,540 FTEs, and the demand is estimated to be 68,040 FTEs, yielding a national level surplus of 42,500 FTE NPs (62 percent of 2025 demand). The 2025 supply of primary care PAs is estimated to be 58,770 FTEs, and the demand is 39,060 FTEs, resulting in a surplus of 19,710 FTEs (50 percent of 2025 demand). Across all providers, aging and population growth account for the majority of increases in demand (86 to 90 percent). The remaining increases in demand for each provider type reflect expanded insurance coverage under the Affordable Care Act.

Table 2.

Primary Care Provider Supply and Demand, 2025

| Physicians | Nurse Practitioners (NPs) | Physician Assistants (PAs) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supply (S ) | Demand (D) | S –D | Adequacy (%) | Supply (S) | Demand (D) | S –D | Adequacy (%) | Supply (S) | Demand (D) | S –D | Adequacy (%) | |

| United States | 239,460 | 263,100 | −23,640 | −9 | 110,540 | 68,040 | 42,500 | 62 | 58,770 | 39,060 | 19,710 | 50 |

| Northeast | 44,110 | 44,920 | −810 | −2 | 15,790 | 11,650 | 4,140 | 36 | 9,450 | 6,580 | 2,870 | 44 |

| New England | ||||||||||||

| Connecticut | 2,860 | 3,000 | −140 | −5 | 1,190 | 770 | 420 | 55 | 710 | 440 | 270 | 61 |

| Maine | 1,270 | 1,050 | 220 | 21 | 640 | 270 | 370 | 137 | 410 | 150 | 260 | 173 |

| Massachusetts | 6,470 | 5,580 | 890 | 16 | 2,420 | 1,430 | 990 | 69 | 880 | 820 | 60 | 7 |

| New Hampshire | 1,150 | 1,100 | 50 | 5 | 730 | 280 | 450 | 161 | 260 | 160 | 100 | 63 |

| Rhode Island | 840 | 850 | −10 | −1 | 220 | 210 | 10 | 5 | 150 | 130 | 20 | 15 |

| Vermont | 600 | 480 | 120 | 25 | 390 | 130 | 260 | 200 | 190 | 70 | 120 | 171 |

| Middle Atlantic | ||||||||||||

| New Jersey | 6,470 | 7,530 | −1,060 | −14 | 1,950 | 1,940 | 10 | 1 | 670 | 1,100 | −430 | −39 |

| New York | 15,310 | 15,190 | 120 | 1 | 4,550 | 3,890 | 660 | 17 | 3,890 | 2,220 | 1,670 | 75 |

| Pennsylvania | 9,140 | 10,140 | −1,000 | −10 | 3,700 | 2,600 | 1,100 | 42 | 2,290 | 1,480 | 810 | 55 |

| Midwest | 47,650 | 52,970 | −5,320 | −10 | 21,570 | 13,690 | 7,880 | 58 | 10,000 | 7,910 | 2,090 | 26 |

| East North Central | ||||||||||||

| Illinois | 9,620 | 10,020 | −400 | −4 | 3,290 | 2,560 | 730 | 29 | 1,380 | 1,500 | −120 | −8 |

| Indiana | 3,920 | 5,100 | −1,180 | −23 | 2,240 | 1,300 | 940 | 72 | 360 | 760 | −400 | −53 |

| Michigan | 6,940 | 7,900 | −960 | −12 | 2,870 | 2,030 | 840 | 41 | 1,940 | 1,180 | 760 | 64 |

| Ohio | 7,990 | 9,190 | −1,200 | −13 | 3,470 | 2,350 | 1,120 | 48 | 810 | 1,370 | −560 | −41 |

| Wisconsin | 4,260 | 4,420 | −160 | −4 | 1,900 | 1,130 | 770 | 68 | 900 | 660 | 240 | 36 |

| West North Central | ||||||||||||

| Iowa | 2,020 | 2,220 | −200 | −9 | 1,000 | 570 | 430 | 75 | 710 | 330 | 380 | 115 |

| Kansas | 1,930 | 2,220 | −290 | −13 | 1,140 | 560 | 580 | 104 | 700 | 330 | 370 | 112 |

| Minnesota | 4,590 | 4,290 | 300 | 7 | 2,360 | 1,100 | 1,260 | 115 | 1,310 | 640 | 670 | 105 |

| Missouri | 3,930 | 5,150 | −1,220 | −24 | 1,890 | 1,310 | 580 | 44 | 530 | 770 | −240 | −31 |

| Nebraska | 1,330 | 1,360 | −30 | −2 | 740 | 340 | 400 | 118 | 700 | 200 | 500 | 250 |

| North Dakota | 520 | 480 | 40 | 8 | 290 | 120 | 170 | 142 | 260 | 70 | 190 | 271 |

| South Dakota | 600 | 610 | −10 | −2 | 390 | 160 | 230 | 144 | 400 | 90 | 310 | 344 |

| South | 84,690 | 98,550 | −13,860 | −14 | 43,540 | 25,470 | 18,070 | 71 | 21,150 | 14,730 | 6,420 | 44 |

| South Atlantic | ||||||||||||

| Delaware | 710 | 820 | −110 | −13 | 290 | 210 | 80 | 38 | 170 | 120 | 50 | 42 |

| District of Columbia | 1,070 | 400 | 670 | 168 | 180 | 100 | 80 | 80 | 120 | 60 | 60 | 100 |

| Florida | 14,620 | 17,680 | −3,060 | −17 | 7,640 | 4,520 | 3,120 | 69 | 3,530 | 2,650 | 880 | 33 |

| Georgia | 7,000 | 8,310 | −1,310 | −16 | 3,230 | 2,120 | 1,110 | 52 | 1,880 | 1,240 | 640 | 52 |

| Maryland | 5,300 | 5,060 | 240 | 5 | 1,600 | 1,300 | 300 | 23 | 1,050 | 760 | 290 | 38 |

| North Carolina | 7,620 | 8,640 | −1,020 | −12 | 3,550 | 2,200 | 1,350 | 61 | 3,180 | 1,290 | 1,890 | 147 |

| South Carolina | 3,220 | 3,940 | −720 | −18 | 1,700 | 1,010 | 690 | 68 | 640 | 590 | 50 | 8 |

| Virginia | 6,350 | 6,970 | −620 | −9 | 3,620 | 1,780 | 1,840 | 103 | 1,520 | 1,040 | 480 | 46 |

| West Virginia | 1,280 | 1,460 | −180 | −12 | 720 | 380 | 340 | 89 | 480 | 220 | 260 | 118 |

| East South Central | ||||||||||||

| Alabama | 2,680 | 3,870 | −1,190 | −31 | 1,080 | 980 | 100 | 10 | 260 | 580 | −320 | −55 |

| Kentucky | 2,560 | 3,520 | −960 | −27 | 1,300 | 900 | 400 | 44 | 640 | 520 | 120 | 23 |

| Mississippi | 1,490 | 2,220 | −730 | −33 | 1,210 | 570 | 640 | 112 | 70 | 330 | −260 | −79 |

| Tennessee | 4,410 | 5,460 | −1,050 | −19 | 3,100 | 1,400 | 1,700 | 121 | 940 | 820 | 120 | 15 |

| West South Central | ||||||||||||

| Arkansas | 1,820 | 2,410 | −590 | −24 | 1,210 | 620 | 590 | 95 | 160 | 360 | −200 | −56 |

| Louisiana | 2,830 | 3,500 | −670 | −19 | 1,180 | 900 | 280 | 31 | 420 | 520 | −100 | −19 |

| Oklahoma | 2,320 | 3,150 | −830 | −26 | 1,200 | 800 | 400 | 50 | 830 | 470 | 360 | 77 |

| Texas | 19,390 | 21,150 | −1,760 | −8 | 10,730 | 5,380 | 5,350 | 99 | 5,250 | 3,150 | 2,100 | 67 |

| West | 62,990 | 66,660 | −3,670 | −6 | 29,640 | 17,230 | 12,410 | 72 | 18,180 | 9,840 | 8,340 | 85 |

| Mountain | ||||||||||||

| Arizona | 6,050 | 7,040 | −990 | −14 | 3,450 | 1,800 | 1,650 | 92 | 1,990 | 1,040 | 950 | 91 |

| Colorado | 4,800 | 4,640 | 160 | 3 | 2,300 | 1,180 | 1,120 | 95 | 2,150 | 680 | 1,470 | 216 |

| Idaho | 1,100 | 1,350 | −250 | −19 | 630 | 340 | 290 | 85 | 610 | 200 | 410 | 205 |

| Montana | 700 | 750 | −50 | −7 | 380 | 190 | 190 | 100 | 330 | 110 | 220 | 200 |

| Nevada | 2,270 | 2,780 | −510 | −18 | 1,190 | 710 | 480 | 68 | 710 | 410 | 300 | 73 |

| New Mexico | 1,660 | 1,780 | −120 | −7 | 1,050 | 450 | 600 | 133 | 610 | 260 | 350 | 135 |

| Utah | 1,770 | 2,370 | −600 | −25 | 980 | 610 | 370 | 61 | 790 | 350 | 440 | 126 |

| Wyoming | 340 | 400 | −60 | −15 | 160 | 100 | 60 | 60 | 280 | 60 | 220 | 367 |

| Pacific | ||||||||||||

| Alaska | 660 | 580 | 80 | 14 | 530 | 150 | 380 | 253 | 510 | 90 | 420 | 467 |

| California | 32,470 | 34,020 | −1,550 | −5 | 13,620 | 8,700 | 4,920 | 57 | 7,290 | 5,030 | 2,260 | 45 |

| Hawaii | 1,210 | 1,130 | 80 | 7 | 410 | 290 | 120 | 41 | 210 | 170 | 40 | 24 |

| Oregon | 3,650 | 3,520 | 130 | 4 | 1,690 | 900 | 790 | 88 | 870 | 520 | 350 | 67 |

| Washington | 6,310 | 6,290 | 20 | 0 | 3,240 | 1,610 | 1,630 | 101 | 1,830 | 930 | 900 | 97 |

U.S. Census Bureau Regions are shown in bold and Divisions are italicized (http://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf).

Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

Adequacy = 100 * [projected 2025 supply (S) − projected 2025 demand (D)]/[projected 2025 demand (D)].

Projections reflect baseline assumptions regarding supply, demand, new entrants into each profession, retirement patterns, and provider‐utilization ratios.

These findings are consistent with recent projections prepared for the Association of American Medical Colleges (IHS 2016), which estimated a shortfall between 14,900 and 35,600 primary care physicians by 2025. IHS also estimated that total U.S. physician shortages may range from 61,700 to 94,700 by 2025, suggesting primary care physician deficits are only one component of a larger health care challenge.

The HWSM projections reflect baseline assumptions regarding supply, demand, new entrants into each profession, retirement patterns, and provider‐utilization ratios. Projected shortages and surpluses must be considered in the context of those assumptions. For example, if the national baseline shortage of primary care physicians is greater than the assumed 8,200 physicians needed to de‐designate the HPSAs, then the 2025 shortages may be greater than estimated by the HWSM. Similarly, if 2013 primary care NP and PA demands are greater than baseline supplies, then the 2025 demands may be higher than projected, which could reduce projected surpluses of NPs and exacerbate projected shortages of PAs.

Regional and State‐Level Findings

The modest shortages of primary care physicians in 2013 and 2025 (−4 percent of 2013 demand and −9 percent of 2025 demand) mask considerable variation in physician supply and demand at regional and state levels. Similarly, both the baseline equilibrium and 2025 surpluses estimated for NPs and PAs at the national level obscure important differences in provider adequacy across the United States.

At the regional level, 2013 primary care physician adequacy ranges from −11 percent of 2013 demand (a shortage) in the South Region to 5 percent of 2013 demand (a surplus) in the Northeast Region (Table 1). Comparable ranges in 2013 regional adequacy are observed for primary care NPs and PAs. For NPs, 2013 adequacy is lowest in the Midwest Region (−7 percent of 2013 demand) and highest in the South Region (6 percent of 2013 demand). For PAs, 2013 adequacy is also lowest in the Midwest Region (−12 percent of 2013 demand), while 2013 adequacy is highest in the West Region (18 percent of 2013 demand). The 2013 geographic distribution of NPs and PAs complements each other in the South and West regions. In the Midwest Region, both NP and PA supplies are in deficit in 2013, while physician supply appears to be close to adequate (−2 percent of 2013 demand).

Primary care provider distribution at the state level reveals even more variability. In 2013, 29 states have shortages of primary care physicians, with 18 states having shortages of 10 percent or more (Table 1). Shortages are particularly marked in the South, where, of the 17 jurisdictions, only Maryland and the District of Columbia have physician surpluses. Primary care physician shortages in the South Region range from 1 percent of 2013 demand in Delaware to 27 percent of 2013 demand in Mississippi. Shortages in primary care physicians are also notable in the Mountain Division of the West Region in 2013, with five of eight states having primary care physician deficits. These shortages range from 10 percent of 2013 demand in Wyoming to 23 percent of 2013 demand in Utah.

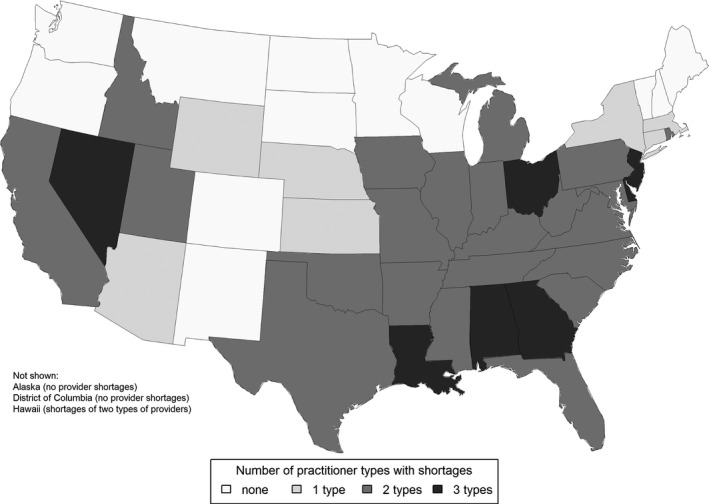

A number of states with 2013 primary care physician shortages also have shortages of primary care NPs and PAs (Table 1; Figure 1). For example, Alabama has a physician shortage estimated at 23 percent of 2013 physician demand coupled with an NP shortage of 14 percent of 2013 NP demand and a PA shortage of 75 percent of 2013 PA demand. Estimates for Louisiana and Nevada tell similar stories. Looking across provider type, Louisiana reveals shortages of all three primary care provider types: 14 percent of physician demand, 11 percent of NP demand, and 50 percent of PA demand. Nevada's provider shortages are 21 percent of physician demand, 32 percent of NP demand, and 11 percent of PA demand.

Figure 1.

States with Shortages of Primary Care Providers, 2013

Note. Projections reflect baseline assumptions regarding supply, demand, new entrants into each profession, retirement patterns, and provider‐utilization ratios.

By 2025, primary care physician shortages become pervasive across all regions, with the greatest shortage expected in the South region, where the deficit is 14 percent of 2025 demand (Table 2). Although all regions are predicted to have surpluses of both primary care NPs and PAs by 2025, these regional surpluses are variable. For NPs, surpluses range from 36 percent of 2025 demand in the Northeast Region to 72 percent of demand in the West Region. For PAs, surpluses range from 26 percent of 2025 demand in the Midwest Region to 85 percent of demand in the West Region.

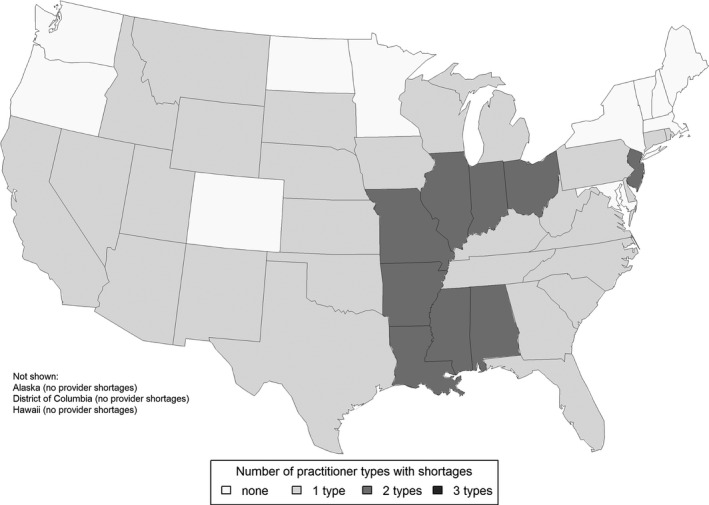

State‐level projections of primary care physician adequacy in 2025 are again quite variable, with the projected severity of the 2025 shortages greater than in 2013. Thirty‐seven states are expected to have shortages of primary care physicians in 2025, of which eight states will be unable to meet 20 percent or more of their demand in 2025. In addition, nine states are projected to have shortages of both primary care physicians and PAs (Table 2; Figure 2). While no state is projected to have a 2025 shortage of primary care NPs, many states are expected to have only small surpluses. Of particular note are two states, Alabama and New Jersey, where there are projected shortages of both physicians and PAs combined with only small surpluses of NPs.

Figure 2.

States with Shortages of Primary Care Providers, 2025

Note. Projections reflect baseline assumptions regarding supply, demand, new entrants into each profession, retirement patterns, and provider‐utilization ratios.

Unlike 2013 when seven states had shortages in all three types of primary care providers, no states are expected to have 2025 shortages of all providers. Across provider types, 27 states are expected to improve their overall provider adequacy (as measured by the number of primary care practitioner types that have an estimated shortage), while 19 states and the District of Columbia are projected to maintain their level of provider adequacy (again, based on the number of primary care practitioner types that have a shortage). Only four states (Montana, New Mexico, South Dakota, and Wisconsin) are expected to transition from having no provider shortages in 2013 to having a shortage of at least one type of primary care provider in 2025.

Discussion

Expectations of increased demand for primary care have generated considerable concern about physician shortages and deteriorating access to primary care (Petterson et al. 2012). This article looks forward to assess future provider availability and finds that, under current patterns of service delivery and physician recruitment, the availability of primary care physicians will decline nationwide, with all U.S. regions projected to experience physician shortages. Moreover, the geographic distribution of physicians is projected to become increasingly skewed, potentially leading to serious access problems. In 2013, 29 states had shortages of primary care physicians. This situation worsens in 2025 when the number of states with physician shortages increases to 37. These findings are consistent with other work reporting distributional imbalances (Huang and Finegold 2013). Moreover, shifts toward smaller population‐to‐primary care physician ratios may lead to greater shortages than are suggested by current projection models (Grover, Orlowski, and Erikson 2016).

Physicians, NPs, and PAs all contribute significantly to the provision of primary care (Petterson et al. 2015). Indeed, NPs and PAs constitute more than 40 percent of the primary care workforce (HHS/AHRQ 2014). While physician recruitment to primary care, especially in underserved and rural areas, is limited, the number of NPs and PAs in primary care has been growing (Pohl, Barksdale, and Werner 2014). By 2025, all U.S. regions and states are projected to have a surplus of primary care NPs, and all but nine states are projected to have a surplus of primary care PAs. Furthermore, no state is projected to be deficient in all three provider types.

Suggested solutions to ensuring adequate and equitable access to primary care reflect a number of interrelated factors beyond workforce distribution. These include recruitment and retention; team members and roles; provider scopes of practice; payment models; and delivery modes (Grover, Orlowski, and Erikson 2016). Given that it takes an average of 6 to 8 years of education and training to produce new NPs and PAs, compared with 11 to 12 years (or more) for physicians, the potential to overcome geographic disparity in primary care access by focusing on NPs and PAs seems attractive, especially as NP and PA supplies are largely expected to be sufficient over the next decade according to the HWSM projections. Here, we consider two solutions to effectively use NPs and PAs to overcome geographic barriers to access: team‐based care and expanded scopes of practice.

Workforce Solutions to Challenges—Team‐Based Care

Recognizing the rise in chronic health conditions and disabilities, including asthma, obesity, behavioral health conditions, and neurodevelopmental disorders (Porter, Pabo, and Lee 2013), many health systems are responding through reorganization. One such approach seeks to create stronger links between local primary care providers and specialty care available at regional centers (Perrin, Anderson, and Van Cleave 2014; Totten et al. 2016). Primary care providers can effectively handle common routine conditions and can also effectively monitor treatment for complex illnesses.

Porter et al. also offer a framework for rethinking primary care, suggesting that primary care be organized around groups of patients with similar needs, increased focus on team‐based care, and better integration of primary care with specialty providers (Porter, Pabo, and Lee 2013).

Simulation modeling has shown that the use of care teams, together with improved information technology and data sharing, can meaningfully increase access to care and offset physician shortages (Green, Savin, and Lu 2013). Care teams, including NPs and PAs, working with primary care physicians, have been found to reduce costs and hospital readmissions for elderly patients with complex health needs (Melnick, Green, and Rich 2016). Although small or isolated populations may make it hard to cost‐effectively implement in‐person team‐based care models (Doescher et al. 2014), the use of telehealth coupled with the effective integration of primary care practitioners into regionalized care teams can help to alleviate these limitations. Geographic analyses, such as introduced here, can support the planning needed to implement such approaches.

Workforce Solutions to Challenges—Expanding Scopes of Practice

Nurse practitioners and PAs effectively augment and expand physician capacity in many care settings (Horrocks, Anderson, and Salisbury 2002; Rohrer et al. 2013). Moreover, NPs and PAs offer a timely and cost‐effective remedy for projected provider shortages (AANP 2013; Riley, Litsch, and Cook 2016). NPs and PAs may be particularly essential in ensuring access to care for underserved populations (Grumbach et al. 2003).

Yet in 27 of the 37 states with 2013 provider shortages, NPs have reduced or restricted scopes of practice (as of May 2016; AANP 2016). In approximately half of these 37 states, PAs also have less than full practice opportunities (AAPA 2016). As a result, NPs and PAs are not able to practice to the full extent of their training and preparation, and direct access to full services provided by NPs and PAs may be constrained for certain populations. Assuming that scopes of practice are unchanged in 2025, NPs and PAs are restricted from full scopes of practice in more than half of states with shortages of one or more provider types.

The demand for primary care services is expected to increase with the aging and growth of the population with multiple chronic conditions and the passing of the ACA. Nationwide, the number of states removing scope of practice restrictions has increased over the last several years, and the movement is to allow full practice authority for NPs (Tolbert 2013). Research suggests that if scope of practice restrictions is removed, NPs have the potential to increase access to primary care, particularly in medically underserved areas, and increase quality outcomes (IOM 2010; NGA 2012; Martsolf, Auerbach, and Arifkhanova 2015). Several studies have compared the impact of care provided by physicians and NPs (Newhouse et al. 2011; Johantgen et al. 2012; Tolbert 2013; Martinez‐Gonzalez et al. 2014). The results of these studies indicate that NPs provide at least equal quality of care to patients as compared to physicians; NPs are able to successfully manage chronic conditions with good outcomes; and NPs are favored in patient satisfaction scores and in achieving patient compliance with health care recommendations. Based on these findings, it may be necessary to address state licensure and scope of practice laws relating to NPs and PAs that currently limit the services these practitioners can deliver to improve access to care, especially in medically underserved areas; increase care efficiency; and decrease costs. These findings also suggest the importance of continuing to develop state compacts, allowing NPs and PAs who are licensed in one state to have reciprocity with other states.3 Currently, 25 states have adopted the Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC), which allows an Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN) to hold one multistate license and have the privilege to practice in any of the other compact states. The migration of nurses out of states where they were licensed is a significant issue in many states, and the NLC has provided more flexibility with regard to mobility. The NLC also increases opportunities for nurses who are practicing in telehealth environments. The state boards of nursing are ensuring that the NLC reflects best practices and high‐quality care (NCSBN 2015).

Limitations

A major limitation of these projections is the uncertainty in how health care use and delivery will evolve over time. The ongoing collection of information to characterize these dynamics will greatly help to improve workforce projections.

It must be reiterated that these projections reflect assumptions about the relationship between supply and demand at baseline, and the findings must be interpreted in the context of those assumptions. For NPs and PAs, baseline supply and demand were assumed to be in equilibrium, while, for physicians, demand was assumed to be equal to 2013 supply plus the approximately 8,200 physicians needed to de‐designate the primary care HPSAs. If the baseline supplies of NPs and PAs, for example, are less than baseline demands, then projected 2025 NP and PA supplies may, in fact, be balanced by projected demands.

Conclusion

Health Resources and Services Administration's recently released health workforce projections suggest primary care provider shortages through 2025. Deficits are particularly notable in the Midwest and South, where physician shortages are coupled with shortages of other primary care providers. These findings must be interpreted in the context of baseline assumptions regarding supply, demand, provider‐service ratios, and other factors. Still, these findings reveal geographies with likely future primary care shortages and suggest opportunities for increasing workforce flexibility through greater focus on team care and expanding NP and PA scopes of practice. These findings also underscore the importance of continuing to strengthen health workforce modeling to improve estimates of provider supply and demand.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Timothy Dall and the health workforce projections modeling teams at IHS Global Inc. and The Center for Health Workforce Studies at SUNY Albany for their work in developing HRSA's primary care provider projections. All authors are full‐time employees of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). The views, analyses, and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimer: None.

Notes

Some definitions of primary care include gynecologists and obstetricians who may provide primary care to women. These providers are not included in the HWSM primary care projections, consistent with the Association of American Medical Colleges’ 2016 report (IHS Inc 2016) and with legislation governing the Medicare and Medicaid programs presented in the Reconciliation Act of 2010. Physician estimates also do not include hospitalists.

Physicians include providers who have a Doctor of Medicine or Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine degree and who have completed their graduate medical education. Full‐time equivalent (FTE) estimates do not include residents or fellows pursuing graduate medical education.

Expanded state license reciprocity for physicians may also help to address physician shortages (Rogove and Stetina 2015).

References

- American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) . 2016. “What Is a PA?” [accessed February 17, 2016]. Available at https://www.aapa.org/What-is-a-PA/

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) . 2013. “Nurse Practitioner Cost‐Effectiveness” [accessed May 10, 2016]. Available at https://www.aanp.org/aanpqa2/images/documents/publications/costeffectiveness.pdf

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) . 2015a. “NP Infographic: Nurse Practitioners” [accessed May 10, 2016]. Available at https://www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/what-is-an-np-2

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) . 2015b. “NP Fact Sheet” [accessed May 10, 2016]. Available at https://www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) . 2016. “State Practice Environment” [accessed May 11, 2016]. Available at https://www.aanp.org/legislation-regulation/state-legislation/state-practice-environment

- Doescher, M. P. , Andrilla C. H. A., Skillman S. M., Morgan P., and Kaplan L.. 2014. “The Contribution of Physicians, Physician Assistants, and Nurse Practitioners Toward Rural Primary Care: Findings from a 13‐State Survey.” Medical Care 52 (6): 549–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dummer, T. J. B. 2008. “Health Geography: Supporting Public Health Policy and Planning.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 178 (9): 1177–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, L. V. , Savin S., and Lu Y.. 2013. “Primary Care Physician Shortages Could Be Eliminated through Use of Teams, Nonphysicians, and Electronic Communication.” Health Affairs 32 (1): 11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover, A. , Orlowski J. M., and Erikson C. E.. 2016. “The Nation's Physician Workforce and Future Challenges.” American Journal of the Medical Sciences 351 (1): 11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumbach, K. , Hart L. G., Mertz E., Coffman J., and Palazzo L.. 2003. “Who Is Caring for the Underserved? A Comparison of Primary Care Physicians and Nonphysician Clinicians in California and Washington.” Annals of Family Medicine 1 (2): 97–104 [accessed May 11, 2016]. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1466573/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Research and Educational Trust (HRET) . 2015. “Community Factors Substantially Influence Hospital Readmission Rates” [accessed February 12, 2016]. Available at http://www.hsr.org/hsr/abouthsr/content/Community_Factor_Substantially_HSR_PR_Jan2015.pdf

- Herrin, J. , Andre J. St., Kenward K., Joshi M. S., Audet A‐M. J., and Hines S. C.. 2014. “Community Factors and Hospital Readmission Rates.” Health Services Research, published online April 9, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker, R. S. , and Muchow A.. 2015. “Modifying State Laws for Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants Can Reduce Cost of Medical Services.” Nursing Economics, 33 (2): 88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks, S. , Anderson E., and Salisbury C.. 2002. “Systematic Review of Whether Nurse Practitioners Working in Primary Care Can Provide Equivalent Care to Doctors.” British Medical Journal 324: 819–23 [accessed May 11, 2016]. Available at http://www.bmj.com/content/324/7341/819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, E. S. , and Finegold K.. 2013. “Seven Million Americans Live in Areas Where Demand for Primary Care May Exceed Supply by More Than 10 Percent.” Health Affairs 32 (3): 614:21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IHS Inc . 2016. 2016 Update: The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2014 to 2025. Prepared for the Association of American Medical Colleges, Washington, DC: [accessed October 7, 2016]. Available at https://www.aamc.org/download/458082/data/2016_complexities_of_supply_and_demand_projections.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) . 2010. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; Available at http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2010/The-Future-of-Nursing-Leading-Change-Advancing-Health.aspx [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) . 2012. Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM), Committee on the Future of Primary Care, Division of Health Care Services . 1996. “Summary: Definition of Primary Care.” In Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era, edited by Donaldson M. S., Yordy K. D., Lohr K. N., and Vanselow N. A., (p. 1). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johantgen, M. , Fountain L., Zangaro G., Newhouse R., Stanik‐Hutt J., and White K. M.. 2012. “Comparison of Labor and Delivery Care Provided by Certified Nurse‐Midwives and Physicians: A Systematic Review, 1990–2008.” Women's Health Issues 22 (1): 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost, T. S. 2016. “A Critical Year for the Affordable Care Act.” Health Affairs 35 (1): 8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T. Y. , Mortensen K., and Eldridge B.. 2015. “Linking Uninsured Patients Treated in the Emergency Department to Primary Care Shows Some Promise in Maryland.” Health Affairs 34 (5): 796–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurant, M. , Reeves D., Hermens R., Braspenning J., Grol R., and Sibbald B.. 2005. “Substitution of Doctors by Nurses in Primary Care” (Review).” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 18 (2): doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub2 [accessed May 11, 2016]. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15846614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurant, M. , Harmsen M., Wollersheim H., Grol R., Faber M., and Sibbald B.. 2009. “The Impact of Nonphysician Clinicians: Do They Improve the Quality and Cost‐Effectiveness of Health Care Services?” Medical Care Research and Review 66 (6 suppl): 36S–89S [accessed May 10, 2016]. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19880672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez‐Gonzalez, A. N. , Djalali S., Tandjung R., Huber‐Geismann F., Markun S., Wensing M., and Rosemann T.. 2014. “Substitution of Physicians by Nurses in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis.” BMC Health Services Research 14: 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martsolf, G. R. , Auerbach D. I., and Arifkhanova A.. 2015. The Impact of Full Practice Authority for Nurse Practitioners and Other Advanced Practice Registered Nurses in Ohio. Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, CA: [accessed May 11, 2016]. Available at http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR848/RAND_RR848.pdf [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M. , Harvey J. B., Kang R., Shi Y., and Scanlon D. P.. 2016. “Community‐Level Quality Improvement and the Patient Experience for Chronic Illness Care.” Health Services Research 51 (1): 76–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick, G. A. , Green L., and Rich J.. 2016. “House Calls: California Program for Homebound Patients Reduces Monthly Spending, Delivers Meaningful Care.” Health Affairs 35 (1): 28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundinger, M. O. , Kane R. L., Lenz E. R., Totten A. M., Tsai W. Y., Cleary P. D., Friedewald W. T., Siu A. L., and Shelanski M. L.. 2000. “Primary Care Outcomes in Patients Treated by Nurse Practitioners or Physicians.” Journal of the American Medical Association 283 (1): 59–68 [accessed May 10, 2016]. Available at http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=192259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants (NCCPA) . 2016. “2015 Statistical Profile of Certified Physician Assistants” [accessed October 4, 2016]. Available at http://www.nccpa.net/Uploads/docs/2015StatisticalProfileofCertifiedPhysicianAssistants.pdf

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) . 2015. “APRN Compact” [accessed February 18, 2016]. Available at https://www.ncsbn.org/aprn-compact.htm.

- National Governors Association (NGA) . 2012. The Role of Nurse Practitioners in Meeting Increasing Demand for Primary Care. Washington, DC: Health Division, December 2012 [accessed May 10, 2016]. Available at http://www.nga.org/cms/home/nga-center-for-best-practices/center-publications/page-health-publications/col2-content/main-content-list/the-role-of-nurse-practitioners.html [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine/MedlinePlus . 2016. “Choosing a Primary Care Provider” [accessed February 16, 2016]. Available at https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001939.htm

- Naylor, M. D. , and Kurtzman E. T.. 2010. “The Role of Nurse Practitioners in Reinventing Primary Care,” Health Affairs 29 (5): 893–9 [accessed May 10, 2016]. Available at http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/29/5/893.abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse, R. P. , Stanik‐Hutt J., White K. M., Johantgen M., Bass E., Zangaro G., Wilson R., Fountain L., Steinwachs D. M., Heindel L., and Weiner J. P.. 2011. “Advanced Practice Nurse Outcomes 1990–2008: A Systematic Review.” Nursing Economics 29 (5): 1–21 [accessed May 10, 2016]. Available at https://www.nursingeconomics.net/ce/2013/article3001021.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono, T. , Lafortune G., and Schoenstein M.. 2013. “Health Workforce Planning in OECD Countries: A Review of 26 Projection Models from 18 Countries.” OECD Health Working Papers, No. 62, OECD Publishing [accessed October 7, 2016]: 10.1787/5k44t787zcwb-en [DOI]

- Perloff, J. , DesRoches C. M., and Buerhaus P.. 2016. “Comparing the Cost of Care Provided to Medicare Beneficiaries Assigned to Primary Care Nurse Practitioners and Physicians.” Health Services Research. 51 (4): 1407–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, J. M. , Anderson L. E., and Van Cleave J.. 2014. “The Rise in Chronic Conditions among Infants, Children, and Youth Can Be Met with Continued Health System Innovations.” Health Affairs 33 (12): 2099–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petterson, S. M. , Liaw W. R., Phillips R. L., Rabin D. L., Meyers D. S., and Bazemore A. W.. 2012. “Projecting U.S. Primary Care Physician Workforce Needs: 2010–2025.” Annals of Family Medicine 10 (6): 503–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petterson, S. M. , Liaw W. R., Tran C., and Bazemore A. W.. 2015. “Estimating the Residency Expansion Required to Avoid Projected Primary Care Physician Shortages by 2035.” Annals of Family Medicine 13 (2): 107–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, J. , Barksdale D., and Werner K.. 2014. “Revisiting Primary Care Workforce Data: A Future without Barriers for Nurse Practitioners and Physicians.” Health Affairs Blog, July 28, 2014 [accessed May 12, 2016]. Available at http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/07/28/revisiting-primary-care-workforce-data-a-future-without-barriers-for-nurse-practitioners-and-physicians/ [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. E. , Pabo E. A., and Lee T. H.. 2013. “Redesigning Primary Care: A Strategic Vision to Improve Value by Organizing around Patients’ Needs.” Health Affairs 32 (3): 516–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourat, N. , Davis A. C., Chen X., Vrungos S., and Kominski G. F.. 2015. “In California, Primary Care Continuity Was Associated with Reduced Emergency Department Use and Fewer Hospitalizations.” Health Affairs 34 (7): 1113–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley, L. , Litsch T., and Cook M. L.. 2016. “Preparing the Next Generation of Health Care Providers: A Description and Comparison of Nurse Practitioner and Medical Student Tuition in 2015.” Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners 28 (2016): 6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogove, H. , and Stetina K.. 2015. “Practice Challenges of Intensive Care Unit Telemedicine.” Critical Care Clinics 31 (2): 319–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer, J. E. , Angstman K. B., Garrison G. M., Pecina J. L., and Maxson J. A.. 2013. “Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants Are Complements to Family Medicine Physicians.” Population Health Management 16 (4): 242–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharzer, A. , Long S. K., and Anderson N.. 2016. “Access to Care and Affordability Have Improved Following Affordable Care Act Implementation; Problems Remain.” Health Affairs 35 (1): 161–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starfield, B. , and Horder J.. 2007. “Interpersonal Continuity: Old and New Perspectives.” British Journal of General Practice 57 (540): 527–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert, E . 2013. “The Future for Nurse Practitioner Scope of Practice Laws Looks Merry and Bright This Season, Barton Blog” [accessed December 20, 2016]. Available at http://www.bartonassociates.com/2013/12/09/the-future-for-nurse-practitioner-scope-of-practice-laws-looks-merry-and-bright-this-season/

- Totten, A. M. , White‐Chu E. F. Wasson N., Morgan E., Kansagara D., Davis‐O'Reilly C., and Goodlin S.. 2016. “Home‐Based Primary Care Interventions.” Prepared by: Pacific Northwest Evidence‐based Practice Center under Contract No. 290‐2012‐00014‐I. AHRQ Publication No. 15(16)‐EHC036‐EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; [accessed May 10, 2016]. Available at www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ) . 2014. Primary Care Workforce Facts and Stats. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; [accessed May 11, 2016]. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/primary/pcworkforce/index.html [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) . 2014b. “Shortage Designation: Health Professional Shortage Areas and Medically Underserved Areas/Populations” [accessed on May 10, 2016]. Available at http://www.hrsa.gov/shortage/

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), National Center for Health Workforce Analysis (NCHWA) . 2014a. “Technical Documentation for Health Resources Service Administration's Health Workforce Simulation Model” [accessed December 2, 2016]. Available at http://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/projections/simulationmodeldocumentation.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), National Center for Health Workforce Analysis (NCHWA) . 2016a. National and Regional Projections of Supply and Demand for Primary Care Practitioners: 2013‐2025. Rockville, MD: National Center for Health Workforce Analysis; [accessed December 2, 2016]. Available at http://bhw.hrsa.gov/health-workforce-analysis [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), National Center for Health Workforce Analysis (NCHWA) . 2016b. State‐Level Projections of Supply and Demand for Primary Care Practitioners: 2013‐2025. Rockville, MD: National Center for Health Workforce Analysis; [accessed December 2, 2016]. Available at http://bhw.hrsa.gov/health-workforce-analysis [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) . 2015. “Report to Congressional Requestors: Health Care Workforce: Comprehensive Planning by HHS Needed to Meet National Needs.” GAO‐16‐17.

- Wilson, I. B. , Landon B. E., Hirschhorn L. R., McInnes K., Ding L., Marsden P.V., and Cleary P. D.. 2005. “Quality of HIV Care Provided by Nurse Practitioners, Physician Assistants, and Physicians,” Annals of Internal Medicine 143 (10), November 2005 [accessed May 10, 2016]. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16287794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.