Abstract

Redox neutral photocatalytic transformations often require careful pairing of the substrates and photoredox catalysts in order to achieve a catalytic cycle. This can limit the range of viable transformations, as we recently observed in attempting to extend the scope of the photocatalytic synthesis of N-heterocycles using silicon amine protocol (SLAP) reagents to include starting materials that require higher oxidation potentials. We now report that the inclusion of Lewis acids in photocatalytic reactions of organosilanes allows access to a distinct reaction pathway featuring an Ir(III)*/Ir(IV) couple instead of the previously employed Ir(III)*/Ir(II) pathway, enabling the transformation of aromatic and aliphatic aldehydes to thiomorpholines and thiazepanes. The role of the Lewis acid in accepting an electron—either directly or via coordination to an imine—can be extended to other classes of photocatalysts and transformations, including oxidative cyclizations. The combination of light induced reactions and Lewis acids therefore promises access to new pathways and transformations that are not viable using the photocatalysts alone.

Short abstract

The presence of Lewis acids enabled the photocatalystic synthesis of thiomorpholines and thiazepanes. Mechanistic investigations additionally led to new conditions for the synthesis of morpholines and the oxidative cyclization of alkenes.

Introduction

Chiral saturated N-heterocycles are privileged scaffolds for modern drug discovery and are present in an increasing number of newly approved small molecule drugs.1,2 To provide access to these structures3−6 in a predictable manner from readily available starting materials, our group has developed stannyl amine protocol (SnAP) reagents for the one-step transformation of aldehydes and ketones into a wide variety of N-heterocycles.7−14 These reagents and protocols have been widely adopted and have emerged as a leading method for the small scale synthesis of morpholines, piperazines, oxazepanes, diazepanes, and thiomorpholines, including substituted and spirocyclic variants. The SnAP chemistry is characterized by broad substrate scope and versatility under a standard set of reaction conditions, making it ideally suited for preparing libraries of saturated N-heterocycles. The requirement for stoichiometric tin reagents and halogenated solvents, however, renders it unsuited for large-scale reactions and the development of sustainable routes to these important structures.

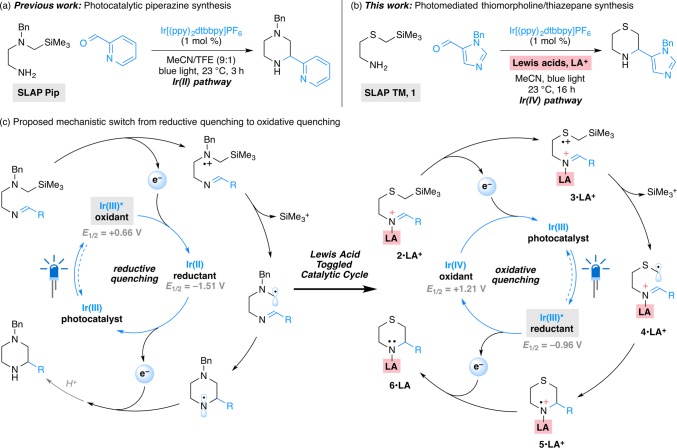

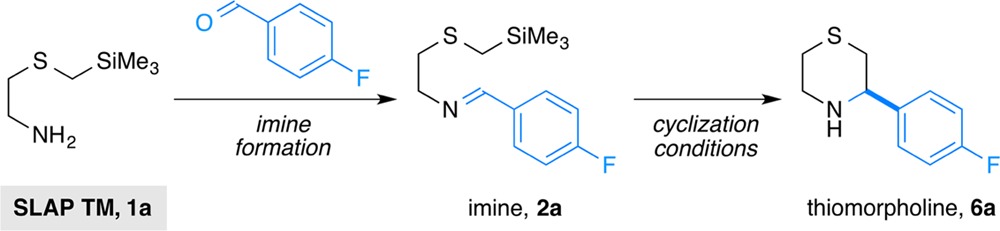

As part of efforts to develop tin-free alternatives to the SnAP reagents, we recently reported the synthesis of N-Bn piperazines using silicon-based SLAP (silicon amine protocol) reagents under photocatalytic conditions (Scheme 1a).15−18 The requisite redox cycle is achieved by the combination of two single-electron transfer events: (1) oxidation of the α-silyl amines (Ep = +0.65 V vs SCE for 1-((trimethylsilyl)methyl)piperidine)19 and (2) reduction of the N-centered radical formed upon radical cyclization (E1/2red > −1.5 V vs SCE for dialkylaminyl radicals or radical cations).20,21 The relatively high reduction potential of the second step necessitated the use of a specific photocatalyst IrIII[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 (Ir(III), where ppy = 2-phenylpyridine, dtbbpy = 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine), one of the few promoters that offer both sufficient oxidation and reduction ability (E1/2*III/II = +0.66 V and E1/2III/II = −1.51 V vs SCE in MeCN)22,23 for N-alkyl and N-aryl piperazine-forming SLAP (SLAP Pip) reagents. Unfortunately, its relatively low oxidation ability was not sufficient for the corresponding SLAP reagents that would form thiomorpholines from α-silyl sulfides (Ep = +1.1–1.4 V vs SCE in MeCN) or morpholines from α-silyl ethers (Ep = +1.90 V vs SCE in MeCN).24−27

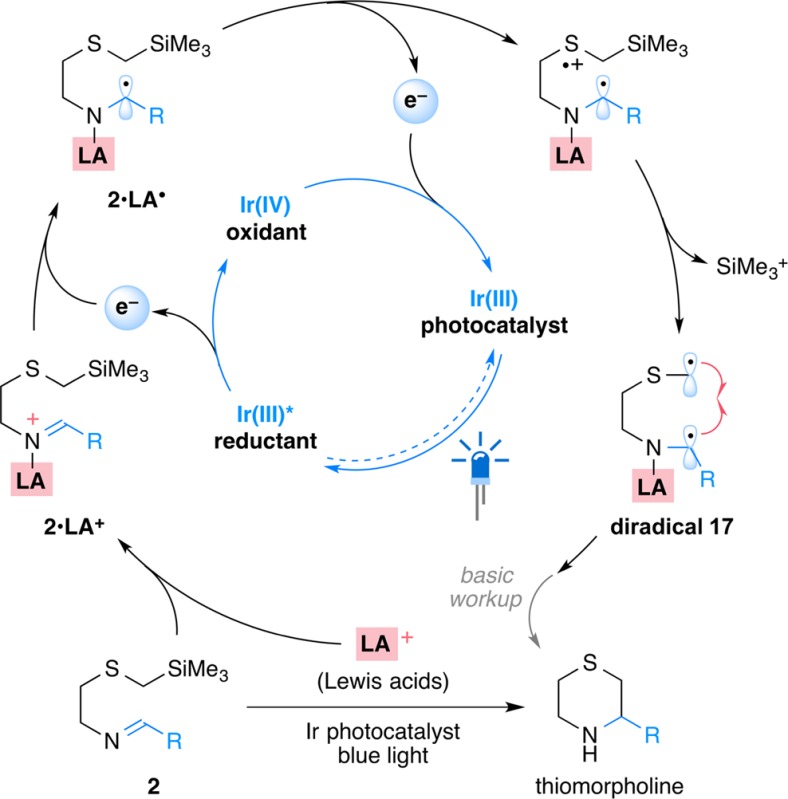

Scheme 1. Photomediated Synthesis of Saturated N-Heterocycles, Such as (a) Piperazines and (b) Thiomorpholines and Thiazepanes, Using SLAP Reagents. (c) Mechanistic Switch in the Presence of Lewis Acids (LA).

We now report that Lewis acid additives are an unexpectedly simple but effective means of accessing an alternative photocatalytic cycle with the same iridium catalyst, one with distinct oxidation and reduction potentials that allow the formation of thiomorpholines from the corresponding SLAP reagents and light (Scheme 1b). Under these conditions, the commercially available IrIII[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 catalyst is effective and can be used to prepare a wide range of thiomorpholine and thiazepane products. Mechanistic studies support reduction of a sacrificial amount of the Lewis acid coordinated imine (2·LA+) by the photoexcited *IrIII[(ppy)2dtbbpy]+ (Ir(III)*), inducing a switch of catalytic pathway to an oxidative quenching cycle (Scheme 1c). The resulting IrIV[(ppy)2dtbbpy]2+ (Ir(IV)) possesses higher oxidation ability (E1/2IV/III = +1.69 V vs SCE in MeCN)22,23 than the photoexcited Ir(III)* (E1/2*III/II = +0.66 V) as an oxidant. It is therefore able to effectively promote single electron oxidation on the sulfur of α-silyl sulfides (2·LA+), desilylation to give 3·LA+, and generation of the C-centered radical 4·LA+. After cyclization, the Lewis acid coordinated N-centered radical (5·LA+) has a lower reduction potential than its uncoordinated counterpart,20,21 allowing the cycle to be completed by reduction with Ir(III)*. In preliminary studies, the combination of Lewis acids and photoredox catalysts28−35 enables transformations not possible with photocatalysts alone and is poised to become a general strategy for expanding the scope of photocatalytic reactions.

Reaction Design

At the outset of our studies with thiomorphoine-forming SLAP (SLAP TM) reagents, we examined photoredox catalysts that provide higher oxidation potentials in their photoexcited states. For example, the excited state species of photocatalyst IrIII[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)PF6 (E1/2*III/II = +1.21 V vs SCE in MeCN; where dF(CF3)ppy = 2-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)pyridine)22,23 should be able to oxidize the α-silyl sulfides of SLAP TM reagents. However, attempted cyclizations with these catalysts led to no desired products, likely due to insufficient ability (E1/2III/II = −1.37 V vs SCE in MeCN)22,23 to reduce the N-centered radical and complete the catalytic cycle.36−38 We therefore questioned in the other case of using IrIII[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 whether it would be possible to access an alternative catalytic cycle: if its photoexcited species Ir(III)* could serve as a reductant, would the resulting Ir(IV) species (E1/2IV/III = +1.21 V vs SCE in MeCN)22,23 be able to oxidize the SLAP TM reagents? More importantly, as the reduction ability of *IrIII[(ppy)2dtbbpy]+ (E1/2*III/IV = −0.96 V vs SCE in MeCN)22,23 seems too low for reducing the uncoordinated N-centered radical, will such radicals be easier to reduce in the presence of suitable additives?

Results and Discussion

Our standard conditions for SnAP chemistry7−14 (Table 1, entry 1) and the previously reported photocatalytic system for SLAP Pip regents15 (entry 2) were not effective, and no formation of thiomorpholine 6a from imine 2a was observed. We therefore surveyed additives that would allow the photocatalyst IrIII[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 to access the oxidative quenching cycle, in which the photoexcited Ir(III)* species functions as a reducing agent. Several potential oxidants,39 including I2, triphenylcarbenium tetrafluoroborate (Ph3C+BF4–), and benzoquinone in the presence of Ir(III) under blue light irradiation, were tested (entry 3). However, the reactions resulted in a mixture of unidentified products and hydrolysis; no desired product was observed.

Table 1. Screening and Optimization of Reaction Conditions with Iminea,b.

| entry | cyclization condition | resultc |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | SnAP conditions: Cu(OTf)2 (1.0 equiv), 2,6-lutidine (1.0 equiv), CH2Cl2/HFIP (4:1) | imine recovered |

| 2 | SLAP N-Bn conditions: Ir[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 (1 mol %), MeCN, BL | imine recovered |

| 3 | oxidants (I2, Ph3C+·BF4–, or benzoquinone, 2.0 equiv), Ir[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 (1 mol %), MeCN, BL | unidentified byproducts |

| 4 | TMSOTf (1.0 equiv), Ir[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 (1 mol %), MeCN, BL | mostly imine recovered |

| 5 | TMSOTf (2.0 equiv), Ir[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 (1 mol %), MeCN, BL | 6a, 34% |

| 6 | TMSOTf (2.0 equiv), MeCN, 60 °C | mostly imine recovered |

| 7 | BF3·MeCN (2.0 equiv), Ir[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 (1 mol %), MeCN, BL | 6a, 36% |

| 8 | Bi(OTf)3 (2.0 equiv), Ir[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 (1 mol %), MeCN, BL | 6a, 56% |

| 9 | Cu(OTf)2 (2.0 equiv), Ir[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 (1 mol %), MeCN, BL | 6a, 42% |

| 10 | Bi(OTf)3 (1.0 equiv), Cu(OTf)2 (1.0 equiv), Ir[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 (1 mol %), MeCN, BL | 6a, 47% |

| 11 | Bi(OTf)3 (0.5 equiv), Cu(OTf)2 (1.0 equiv), Ir[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 (1 mol %), MeCN, BL | 6a, 46% |

Reactions were conducted at 23 °C for 16 h, unless stated otherwise.

Each reaction was performed on a 0.10 mmol scale in 0.1 M concentration.

Calculated yield from 1H NMR measurement of unpurified reaction mixture with 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an additional internal standard. BL = blue light; HFIP = 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoroisopropanol.

We therefore considered activation of the imine with Lewis acids to induce reduction by Ir(III)* and selected trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (TMSOTf) for initial studies. Substoichiometric amounts or a single equivalent of TMSOTf was not effective (entry 4), but the addition of 2 equiv led to the formation of the desired product in 36% yield, as judged by 1H NMR; no significant side products were observed (entry 5). Control experiments confirmed the requirement for TMSOTf, IrIII[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6, and blue light for product formation; TMSOTf alone was not effective in the absence of light or the photocatalyst (entry 6). Various Lewis acids including BF3·MeCN (entry 7), Bi(OTf)3 (entry 8), Cu(OTf)2 (entry 9), and many others (e.g., BiCl3, BiBr3 In(OTf)3, Sc(OTf)3) were found to promote the cyclization. Interestingly, the use of BF3·Et2O did not afford the cyclized product. We also observed that the presence of certain cosolvents including THF and alcohols (e.g., MeOH and HFIP) suppressed the reaction.

Despite the better outcome with Bi(OTf)3 among the Lewis acids in Table 1, our evaluation of the substrate scope (vide infra) revealed that imines from electron-donating aldehydes usually gave superior results with Cu(OTf)2. In the case of thiazepane formation, the use of Bi(OTf)3 was nearly always superior to Cu(OTf)2. Other Lewis acids, including TMSOTf and BF3·MeCN, were almost as effective but gave, in general, slightly lower yields. As a compromise, we combined the two Lewis acids (Bi(OTf)3 (0.5 equiv) and Cu(OTf)2 (1.0 equiv)) to provide a “first-try” general protocol applicable to most substrates (Table 1, entry 11). Substrate specific optimization by changing the Lewis acid can improve the outcome in many examples.

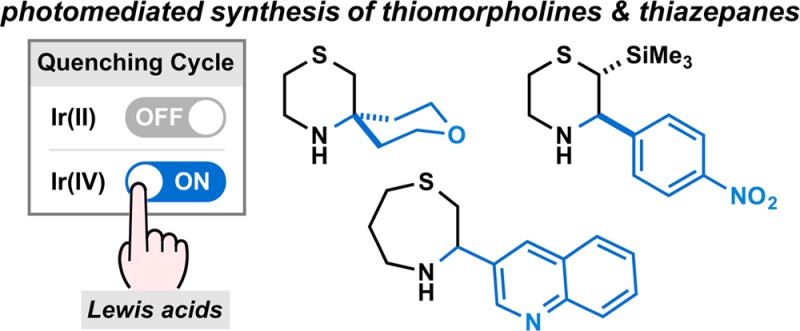

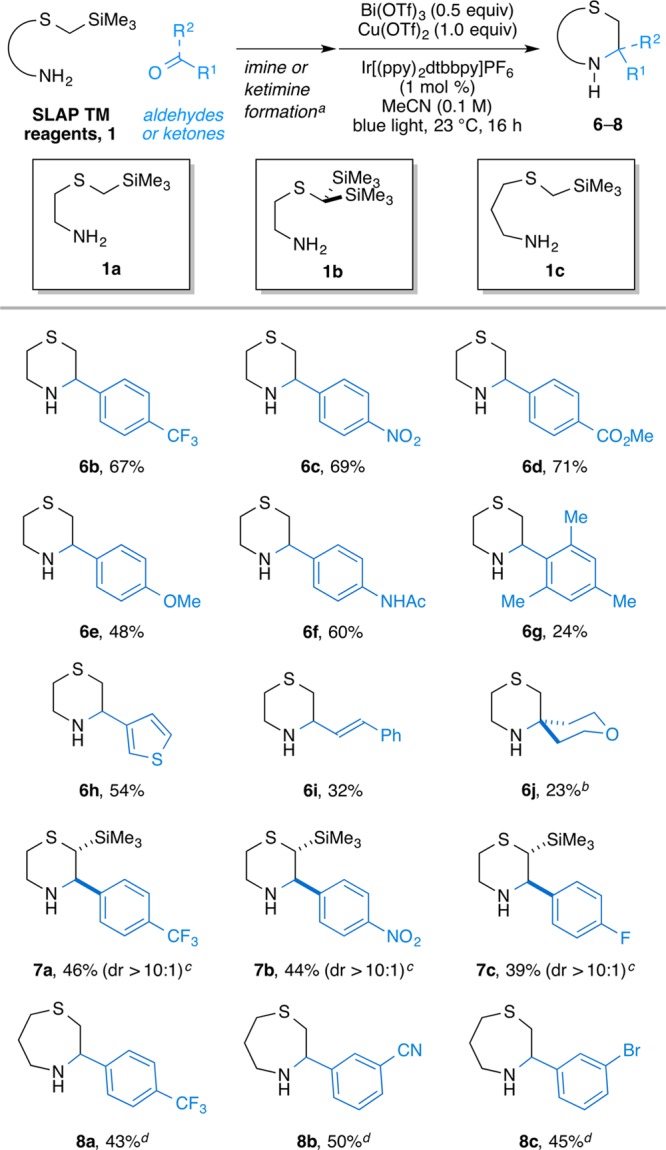

With the optimal reaction conditions in hand, the substrate scope of thiomorpholine and thiazepane formation from a variety of aliphatic and aromatic aldehydes and ketones was examined (Scheme 2). The cyclization tolerated a broad spectrum of different substituents and functional groups. Aliphatic and hindered aldehydes also provided the desired cyclized products, albeit in reduced yields. Interestingly, in the cyclization from the bistrimethylsilyl SLAP reagent 1b, only monodesilylated, 2,3-disubstituted products 7 were generated, always as the trans diastereomers; fully desilylated products were not detected in the unpurified reaction mixture. This observation can be attributed to the lower oxidation potentials of α-bistrimethylsilyl sulfides than the α-monotrimethylsilyl counterparts.24 In addition, these cyclization conditions also allowed for the synthesis of thiazepanes 8, albeit with longer reaction times. This is an important finding, as our attempts at forming thiazepanes with SnAP reagents were plagued by low yield and poor conversion under our standard conditions.

Scheme 2. Substrate Scope of SLAP TM Reagents with Nonheterocyclic Aldehydes and Ketones.

(a) See the Supporting Information for the details. (b) Additional BF3·MeCN (2.0 equiv) and extended reaction time (48 h) were applied. (c) The diastereomeric ratios were determined by 1H NMR measurement of unpurified reaction mixture. (d) Reaction time was 48 h.

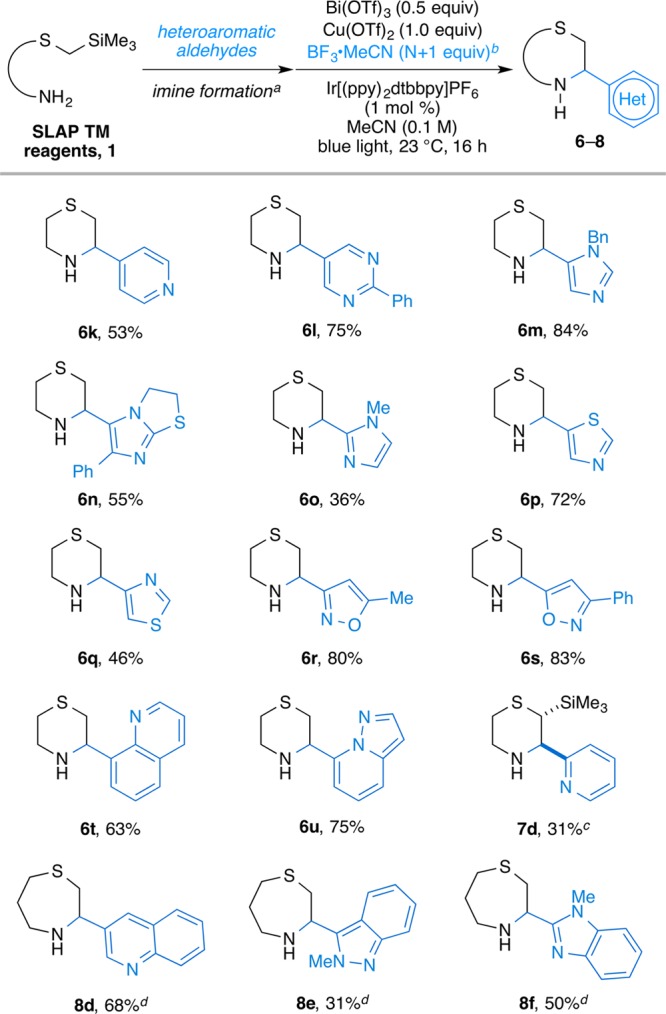

In early evaluations, imines derived from heteroaromatic aldehydes were challenging, likely because the basic nitrogen atoms could bind to the Lewis acids, hampering access to the photocatalytic cycle. By “protecting” the heteroaromatic moieties in situ with BF3·MeCN, followed by a simple basic workup to remove the Lewis acids after the cyclization, we could easily expand the substrate scope to include these important substrates. A series of imines containing different types of heteroaromatic substituents (e.g., pyridine, pyrimidine, isoxazole, thiazole, and imidazole) were examined and found to give the cyclization product in good yields (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Substrate Scope of SLAP TM Reagents with Heterocyclic Aldehydes.

(a) See the Supporting Information for the details. (b) N = the number of heteroatoms on the heterocyclic ring. (c) The diastereomeric ratios were determined by 1H NMR measurement of unpurified reaction mixture. (d) Reaction time was 48 h.

Mechanistic Considerations

We initially considered several possible explanations for the beneficial effect of Lewis acids on the photocyclization to afford thiomorpholines. In one hypothesis, the Lewis acid could coordinate to the sulfur atom of the SLAP TM reagents, thereby modulating their oxidation potentials and allowing the reagents to be oxidized by the Ir(III)*. This hypothesis, however, was both counterintuitive—as coordination should raise, rather than lower, the oxidation potential—and was discounted by electrochemical studies that showed almost no change to the oxidation potential of a model substrate in the presence of Lewis acids.40

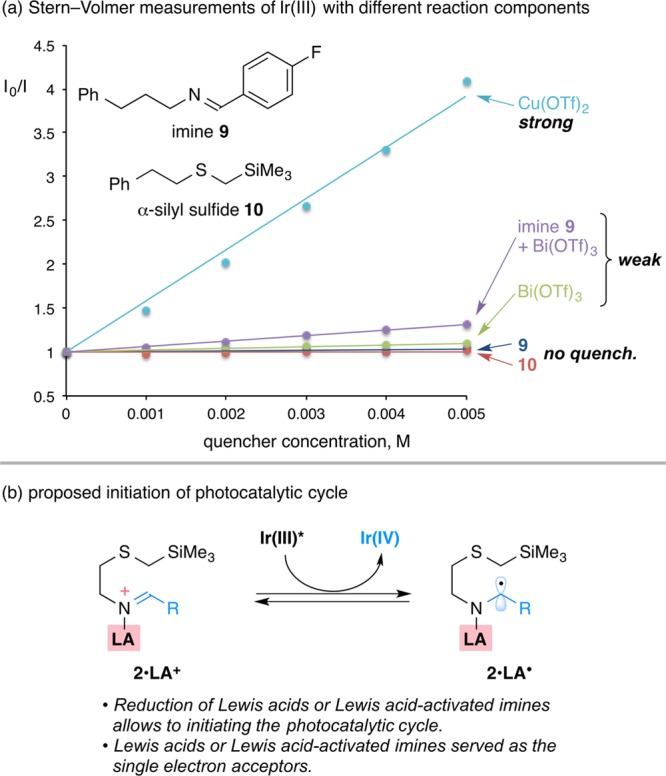

Our favored mechanism features a role for the Lewis acid or the corresponding coordinated imine as an electron acceptor from the photoexcited Ir(III)* species to form the Ir(IV) oxidant. The resulting Ir(IV) species (E1/2IV/III = +1.21 V)22,23 should be able to oxidize the α-silyl sulfide (Ep = +1.1–1.4 V)24−27 to form the C-centered radical that would deliver the N-centered radical followed by cyclization. This stabilized, N-centered radical cation (shown as 5·LA+, Scheme 1c) is regarded as having a lower reduction potential than the uncoordinated N-centered radical,20,21 and can likely be reduced by Ir(III)* to give the Lewis acid coordinated product (6·LA) and complete the catalytic cycle (Scheme 1c). To support this conjecture, we performed Stern–Volmer fluorescence quenching experiments of the current photocatalyst Ir[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 with different reaction components (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Stern–Volmer quenching experiments of Ir[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 (100 μM in MeCN) with different reaction components. (b) Proposed reduction of Lewis acid activated imine.

Neither imine 9 nor α-silyl sulfide 10 alone showed a linear relationship in the Stern–Volmer quenching experiments with IrIII[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 (Figure 1a), which supported the unproductive result from the initial screening of reaction conditions (Table 1, entry 2). Interestingly, further investigations showed that the fluorescence was quenched in the presence of Cu(OTf)2 and Bi(OTf)3 respectively, consistent with favored reduction of Cu(OTf)2 (E0 = +0.8 V vs SCE)39 and Bi(OTf)3 (E0 ca. – 0.1 V vs SCE)41 by the excited species *IrIII[(ppy)2dtbbpy]+ (E1/2*III/IV = −0.96 V vs SCE in MeCN).22,23 The cyclic voltammetry experiment also supported that the reduction of BF3·MeCN (Ep = −0.28 V vs SCE in MeCN) and TMSOTf (Ep = −0.18 V vs SCE in MeCN) be favored by the Ir(III)* species.40 On the other hand, the fluorescence of Ir(III)* was quenched by the Lewis acid activated imines (Figure 1a, the purple line), suggesting that the proposed reduction can also be applied to other Lewis acid–imine complexes, such as those imine complexes with TMSOTf, Bi(OTf)3, and BF3·MeCN. Collectively, these Lewis acids—or more likely their coordinated counterparts—serve as electron acceptors and react with the photoexcited species Ir(III)* to generate Ir(IV) (Figure 1b), which initiates the photocatalytic cycle.42,43 It is worth noting that the product from the final reduction step is the Lewis acid coordinated thiomorpholine (6·LA, Scheme 1c), which is consistent with the need for a superstoichiometric amount of Lewis acid for successful cyclizations.

Equally important to the success of the overall reaction is reduction of the N-centered radical by a photoexcited state Ir(III)* species. Although the Ir(III)* reductant (E1/2*III/IV = −0.96 V)22,23 has a lower reduction potential than the Ir(II) species (E1/2III/II = −1.51 V) formed in the alternative system, we found it to be sufficient to reduce the Lewis acid coordinated N-centered radical (5·LA+). In the case of Cu(II) this is not surprising since the reduced Cu(OTf)–imine complex can be regarded as the same as the Cu(I) species–imine (radical anion) thought to be involved in copper catalyzed SnAP chemistry.7−14

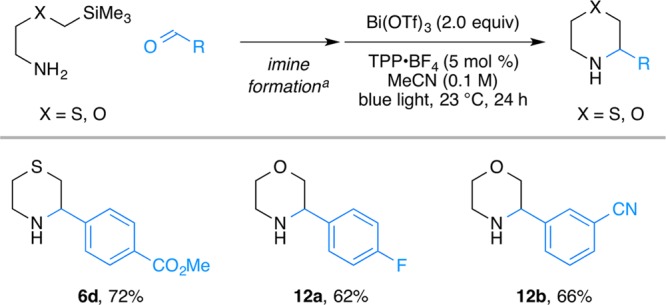

As the Lewis acid–N-centered radical cation complexes are easier to reduce than their uncoordinated variants, this conjecture suggests that photocatalysts with stronger oxidizing abilities (which usually have poorer reducing power) could be used to broaden the substrate scope of the SLAP chemistry. For the synthesis of substituted morpholines, the oxidation of α-silyl ethers (Ep = +1.90 V vs SCE in MeCN)24−27 is challenging, since the current photocatalyst IrIII[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6—even in its Ir(IV) state—is not suited to perform the oxidation. We therefore examined cyclizations with the organic photocatalyst, 2,4,6-triphenylpyrylium tetrafluoroborate (TPP·BF4), selected for its high oxidation ability (E(S*/S•–) = +2.02 V).44−47 While the reduced catalyst has rather low reduction potential (E(S/S–) = −0.32 V), this was sufficient to reduce the Lewis acid coordinated imine. With this system, both thiomorpholines and morpholines can be prepared using TPP·BF4 as the photocatalyst (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Application to the Synthesis of Substituted Morpholines and Thiomorpholines.

(a) See the Supporting Information for the details.

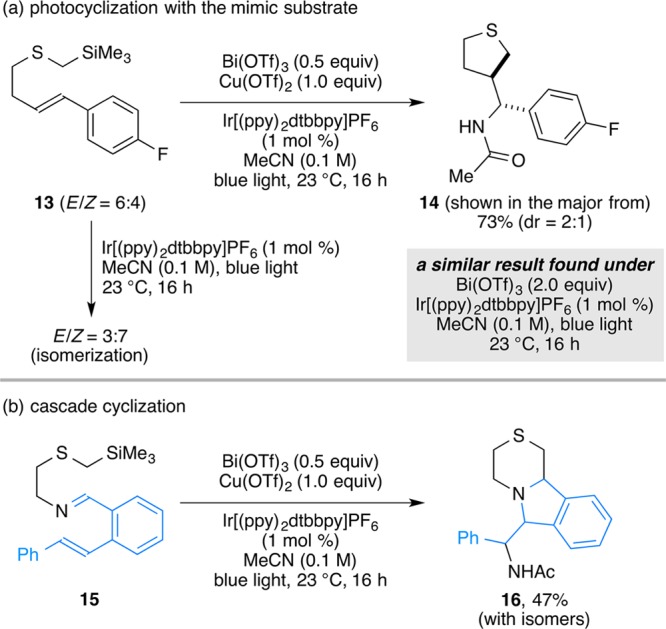

In further studies, we found that the combination of Lewis acids and photocatalytic conditions can lead to processes not typically thought to be viable. For example, alkene 13 gives only alkene isomerization in the presence of Ir[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 with exposure to blue light, but gives cyclic product 14 when sufficient Cu(OTf)2 or Bi(OTf)3 are included in the reaction (Scheme 5). This product is formally a two-electron oxidation, likely via a radical cyclization to form the benzylic radical, which is further oxidized, and the resulting carbocation is trapped with one molecule of acetonitrile.48,49 This implies that 2 equiv of the Lewis acid are reduced in the process. A similar observation was made with imine 15, designed as a probe to capture the formation of the N-centered radical. These studies strongly suggest that the combination of Lewis acids or other electron acceptors can expand the range of accessible transformation available under photomediated conditions.

Scheme 5. Application to (a) the Cyclization of Mimic Substrate Alkene 13 and (b) Cascade Cyclization with Imine 15.

In summary, we have established that the inclusion of Lewis acids in photomediated reactions can induce an alternative photocatalytic cycle from the same Ir[(ppy)2dtbbpy]PF6 catalyst, thereby enabling transformations not available with previous systems. Taking advantage of this phenomenon, we expanded our recently developed SLAP reagents to more challenging thiomorpholine formation. The role of Lewis acids in modulating the reduction potential of the key intermediates can be further extended to other systems, including those mediated by organic photocatalysts. Mechanistic studies also point to a role for Lewis acids as single electron acceptors, resulting in transformations that are formally oxidations. These findings should make possible the development of general conditions for the formation of N-heterocycles from SLAP reagents and enable new photocatalytic transformations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC Starting Grant No. 306793—CASAA). We appreciate the construction of blue light reactors by Dr. Benedikt Wanner (ETH Zürich) and the preliminary investigations from Dr. Cam-Van Vo and Dr. Tuo Jiang (ETH Zürich). We are greatly thankful for insightful discussions on mechanistic studies with Dr. Reinhard Kissner (particularly with the assistance of cyclic voltammetry measurement), Yayi Wang, and Dr. Hsueh-Ju Liu (ETH Zürich). We are also grateful to the Laboratorium für Organische Chemie at ETH Zürich for MS analysis service by Oswald Greter and Louis Bertschi, and for the acquisition of X-ray structures by Dr. Nils Trapp.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00334.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Vitaku E.; Smith D. T.; Njardarson J. T. Analysis of the structural diversity, substitution patterns, and frequency of nitrogen heterocycles among U.S. FDA approved pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 10257–10274. 10.1021/jm501100b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley D. J.; Nelson A.; Marsden S. P. Evaluating new chemistry to drive molecular discovery: fit for purpose?. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 13650–13657. 10.1002/anie.201604193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer J., Ed. Asymmetric Synthesis of Nitrogen Heterocycles; Wiley-VCH Verlag: Weinheim, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schnurch M.; Dastbaravardeh N.; Ghobrial M.; Mrozek B.; Mihovilovic M. D. Functionalization of saturated and unsaturated heterocycles via transition metal catalyzed C–H activation reactions. Curr. Org. Chem. 2011, 15, 2694–2730. 10.2174/138527211796367291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eicher T.; Hauptmann S.; Speicher A.. The Chemistry of Heterocycles: Structure, Reactions, Synthesis, and Applications, 3rd, Compl. Revised and Enlarged ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vo C.-V. T.; Bode J. W. Synthesis of saturated N-heterocycles. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 2809–2815. 10.1021/jo5001252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo C.-V. T.; Mikutis G.; Bode J. W. SnAP reagents for the transformation of aldehydes into substituted thiomorpholines—an alternative to cross-coupling with saturated heterocycles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 1705–1708. 10.1002/anie.201208064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luescher M. U.; Vo C.-V. T.; Bode J. W. SnAP reagents for the synthesis of piperazines and morpholines. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 1236–1239. 10.1021/ol500210z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo C.-V. T.; Luescher M. U.; Bode J. W. SnAP reagents for the one-step synthesis of medium-ring saturated N-heterocycles from aldehydes. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 310–314. 10.1038/nchem.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siau W.-Y.; Bode J. W. One-step synthesis of saturated spirocyclic N-heterocycles with stannyl amine protocol (SnAP) reagents and ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17726–17729. 10.1021/ja511232b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoghegan K.; Bode J. W. Bespoke SnAP reagents for the synthesis of C-substituted spirocyclic and bicyclic saturated N-heterocycles. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1934–1937. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luescher M. U.; Bode J. W. Catalytic synthesis of N-unprotected piperazines, morpholines, and thiomorpholines from aldehydes and SnAP reagents. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10884–10888. 10.1002/anie.201505167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luescher M. U.; Bode J. W. SnAP-eX reagents for the synthesis of exocyclic 3-amino- and 3-alkoxypyrrolidines and piperidines from aldehydes. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 2652–2655. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A brief review for SnAP chemistry, see:Luescher M. U.; Geoghegan K.; Nichols P. L.; Bode J. W. Access saturated N-heterocycles in a SnAP. Aldrichimica Acta 2015, 48, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh S.-Y.; Bode J. W. Silicon amine reagents for the photocatalytic synthesis of piperazines from aldehydes and ketones. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 2098–2101. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inspired by the pioneer work from Yoon and Mariano:Yoon U. C.; Mariano P. S. Mechanistic and synthetic aspects of amine–enone single electron transfer photochemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 1992, 25, 233–240. 10.1021/ar00017a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon U. C.; Kwon H. C.; Hyung T. G.; Choi K. H.; Oh S. W.; Yang S.; Zhao Z.; Mariano P. S. The photochemistry of polydonor-substituted phthalimides: Curtin–Hammett-type control of competing reactions of potentially interconverting zwitterionic biradical intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 1110–1124. 10.1021/ja0305712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho D. W.; Yoon U. C.; Mariano P. S. Studies leading to the development of a single-electron transfer (SET) photochemical strategy for syntheses of macrocyclic polyethers, polythioethers, and polyamides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 204–215. 10.1021/ar100125j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broka K.; Stridins J. P.; Sleiksa I.; Lukevics E. Electrochemical oxidation of several silylated cyclic amines in acetonitrile. Latv. Khim. Z. 1992, 5, 575–579. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson M.; Wayner D. D. M.; Lusztyk J. Redox and acidity properties of alkyl- and arylamine radical cations and the corresponding aminyl radicals. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 17539–17543. 10.1021/jp961286q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wille U.; Heuger G.; Jargstorff C. N-Centered radicals in self-terminating radical cyclizations: experimental and computational studies. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 1413–1421. 10.1021/jo702261u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slinker J. D.; Gorodetsky A. A.; Lowry M. S.; Wang J.; Parker S.; Rohl R.; Bernhard S.; Malliaras G. G. Efficient yellow electroluminescence from a single layer of a cyclometalated iridium complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 2763–2767. 10.1021/ja0345221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry M. S.; Goldsmith J. I.; Slinker J. D.; Rohl R.; Pascal R. A.; Malliaras G. G.; Bernhard S. Single-layer electroluminescent devices and photoinduced hydrogen production from an ionic iridium(III) complex. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 5712–5719. 10.1021/cm051312+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida J.-i.; Maekawa T.; Murata T.; Matsunaga S.; Isoe S. The origin of β-silicon effect in electron-transfer reactions of silicon-substituted heteroatom compounds. Electrochemical and theoretical studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 1962–1970. 10.1021/ja00161a049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida J.-i. Electrochemical reactions of organosilicon compounds. Top. Curr. Chem. 1994, 170, 39–81. 10.1007/3-540-57729-7_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jouikov V. V. Electrochemical reactions of organosilicon compounds. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1997, 66, 509–540. 10.1070/RC1997v066n06ABEH000251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida J.-i.; Kataoka K.; Horcajada R.; Nagaki A. Modern strategies in electroorganic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2265–2299. 10.1021/cr0680843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanam J. M. R.; Stephenson C. R. J. Visible light photoredox catalysis: applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 102–113. 10.1039/B913880N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prier C. K.; Rankic D. A.; MacMillan D. W. C. Visible light photoredox catalysis with transition metal complexes: applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322–5363. 10.1021/cr300503r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckenthäler M.; Griesbeck A. G. Photoredox catalysis for organic syntheses. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 2727–2744. 10.1002/adsc.201300751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Y.; Yi H.; Lei A. Synthetic applications of photoredox catalysis with visible light. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 2387–2403. 10.1039/c3ob40137e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike T.; Akita M. Visible-light-induced photoredox catalysis: an easy access to green radical chemistry. Synlett 2013, 24, 2492–2505. 10.1055/s-0033-1339874. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angnes R. A.; Li Z.; Correia C. R. D.; Hammond G. B. Recent synthetic additions to the visible light photoredox catalysis toolbox. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 9152–9167. 10.1039/C5OB01349F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravelli D.; Protti S.; Fagnoni M. Carbon–carbon bond forming reactions via photogenerated intermediates. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 9850–9913. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw M. H.; Twilton J.; MacMillan D. W. C. Photoredox catalysis in organic chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6898–6926. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organic photocatalysts with higher oxidation abilities were also investigated, such as 2CzIPN and 4DAIPN (refs (37) and (38)). See Supporting Information for more experimental details.

- Uoyama H.; Goushi K.; Shizu K.; Nomura H.; Adachi C. Highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes from delayed fluorescence. Nature 2012, 492, 234–238. 10.1038/nature11687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J.; Zhang J. Donor–acceptor fluorophores for visible-light-promoted organic synthesis: photoredox/Ni dual catalytic C(sp3)–C(sp2) cross-coupling. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 873–877. 10.1021/acscatal.5b02204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly N. G.; Geiger W. E. Chemical redox agents for organometallic chemistry. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 877–910. 10.1021/cr940053x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See Supporting Information for more details.

- Singh S. P.; Karmakar B. Controlled oxidative synthesis of Bi nanoparticles and emission centers in bismuth glass nanocomposites for photonic application. Opt. Mater. 2011, 33, 1760–1765. 10.1016/j.optmat.2011.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Similar initiation of a photocatalytic cycle via the reduction of activated heteroarene species by photoexcited Ir(III)* to obtain Ir(IV) was recently reported. See:Jin J.; MacMillan D. W. C. Alcohols as alkylating agents in heteroarene C–H functionalization. Nature 2015, 525, 87–90. 10.1038/nature14885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An alternative diradical

mechanism was also considered. This mechanism begins from the reduction

of activated imines by photoexcited species Ir(III)* and follows with

the oxidation of α-trimethylsilyl sulfides by Ir(IV), to generate

the diradical species 17. While possible, we consider

it less likely based on both kinetic considerations and the results

on the alkene substrates shown in Scheme 5.

- Searle R.; Williams J. L. R.; DeMeyer D. E.; Doty J. C. The sensitization of stilbene isomerization. Chem. Commun. (London) 1967, 1967, 1165–1165. 10.1039/c19670001165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akaba R.; Sakuragi H.; Tokumaru K. Triphenylpyrylium-salt-sensitized electron transfer oxygenation of adamantylideneadamantane. Product, fluorescence quenching, and laser flash photolysis studies. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1991, 1991, 291–297. 10.1039/p29910000291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Haze O.; Dinnocenzo J. P.; Farid S.; Farid R. S.; Gould I. R. Bonded exciplexes. A new concept in photochemical reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 6970–6981. 10.1021/jo071157d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A recent review on organic photoredox catalysis, see:Romero N. A.; Nicewicz D. A. Organic photoredox catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10075–10166. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recent photocatalytic transformation related to the capture of one molecule of acetonitrile to generate acetamide products, see:Yasu Y.; Koike T.; Akita M. Intermolecular aminotrifluoromethylation of alkenes by visible-light-driven photoredox catalysis. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 2136–2139. 10.1021/ol4006272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Similar traps with acetonitrile and other nitriles, see:Prasad Hari D.; Hering T.; König B. The Photoredox-catalyzed Meerwein addition reaction: intermolecular amino-arylation of alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 725–728. 10.1002/anie.201307051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.