Abstract

The MOF with the encapsulated CO2 molecule shows that the CO2 molecule is ligated to the unsaturated Cu(II) sites in the cage using its Lewis basic oxygen atom via an angular η1-(OA) coordination mode and also interacts with Lewis basic nitrogen atoms of the tetrazole ligands using its Lewis acidic carbon atom. Temperature dependent structure analyses indicate the simultaneous weakening of both interactions as temperature increases. Infrared spectroscopy of the MOF confirmed that the CO2 interaction with the framework is temperature dependent. The strength of the interaction is correlated to the separation of the two bending peaks of the bound CO2 rather than the frequency shift of the asymmetric stretching peak from that of free CO2. The encapsulated CO2 in the cage is weakly interacting with the framework at around ambient temperatures and can have proper orientation for wiggling out of the cage through the narrow portals so that the reversible uptake can take place. On the other hand, the CO2 in the cage is restrained at a specific orientation at 195 K since it interacts with the framework strong enough using the multiple interaction sites so that adsorption process is slightly restricted and desorption process is almost clogged.

Recent global warming is closely related to the increased CO2 concentration in the atmosphere1. One way to tackle the problem is CO2 capture-storage and utilization2,3,4,5. Microporous metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) received great attentions for CO2 capture and utilization6,7,8,9,10,11,12. The properties of a MOF can be modulated to meet necessities for CO2 sequestration agents using not only its organic residues but also metal ions in pore surface.

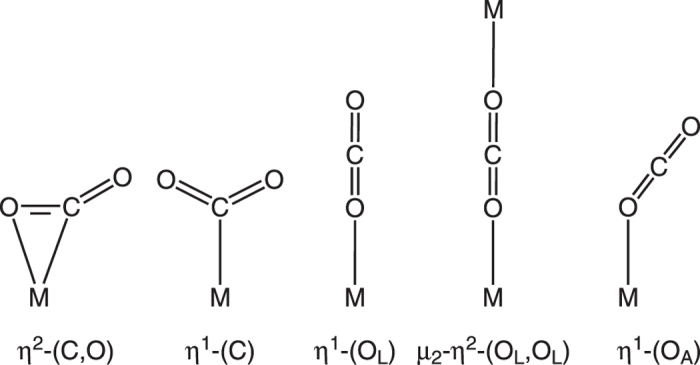

Though there are many structural reports on the CO2 bound species, most of them are of molecular complexes that contain metal sites interacting with CO2 in strong coordination bond such as η2-(C, O)5, η1-(C)6 and linear η1-(OL) coordination modes13 (Fig. 1). There are also several reports on the structural characteristics of the CO2 encapsulated in micropores of MOFs13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, however, the interactions are weak non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, dipole-quadrupole interaction and van der Waals interactions (C- and O-

and O- interactions), only with organic residues in the pore surface.

interactions), only with organic residues in the pore surface.

Figure 1. Coordination modes of CO2 to metal center.

The structural information of the encapsulated CO2 interacting with the framework using multiple binding sites is scarce22. On the other hand, while there are several reports on the vibrational mode analysis of CO2 strongly bound to metal centers13,23,24,25,26,27, only a few investigations on the correlation between the vibrational modes of the encapsulated CO2 weakly interacting with the framework and its structural data are reported16,17,18,19,22,28,29.

Here, we report the temperature dependent single crystal structure analyses of a microporous MOF with bound CO2 in microporous 1-D channels via both a weak angular η1-(OA) coordination of CO2 to Cu(II) sites and a dipole-quadrupole interaction between a Lewis basic atom of a framework and the Lewis acidic carbon atom of CO2. Temperature dependent vibrational modes of bound CO2 are investigated using infrared (IR) spectroscopy together with temperature dependent crystal structures with the encapsulated CO2. Reversible CO2 uptakes at around ambient temperatures but irreversible CO2 uptake at 195 K could be explained based on temperature dependent structural information and vibrational band analyses of the bound CO2.

Results and Discussion

Single crystal structure analyses of the MOF and its CO2-bound MOF derivatives

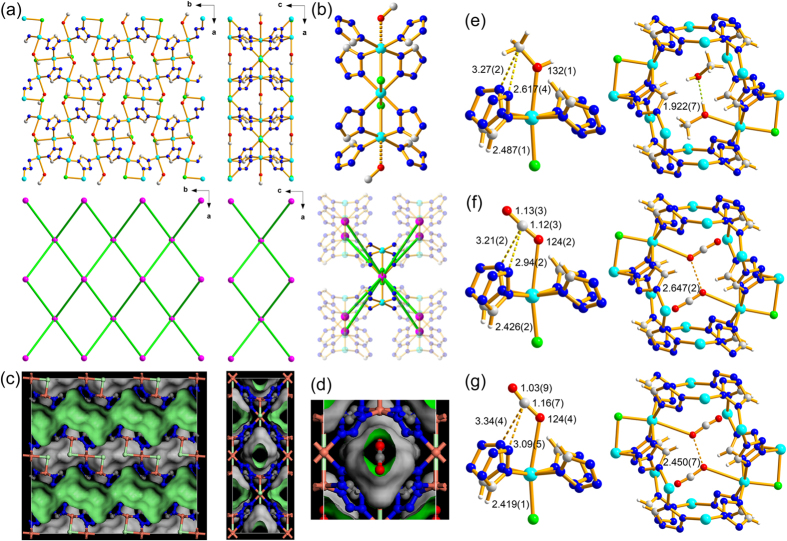

A solvothermal reaction of CuCl2 with tetrazole (tz) in methanol (MeOH)/acetonitrile mixed solvent produced block-shaped blue crystalline product of the formula unit, Cu3Cl2(tz)4(MeOH)2 ((MeOH)2@1a). A single crystal structure analysis revealed that the product is a 3-D MOF of an 8-c bcu topology30 with linear trinuclear [Cu3Cl2] secondary building unit (SBU) as an 8-c node and tridentate tz as a ditopic linker (Fig. 2). A partially occupied methanol molecule is weakly ligated at the Jahn–Teller elongated sixth coordination site of the terminal copper atom (Cu1–O1M: 2.617(4) Å) of the linear trinuclear [Cu3Cl2] SBU (Fig. 2e).

Figure 2.

(a) Ball-and-stick diagrams of 1 viewed along the crystallographic c-axis (left) and b-axis (right), respectively, where [Cu3Cl2] SBU as 8-c nodes are represented by pink spheres and the linkers between the 8-c nodes are represented by the green sticks. (b) A [Cu3Cl2(tz)8] cluster (top) and the [Cu3Cl2] SBU as an 8-c node (bottom). (c) The space-filling diagrams of 1 drawn as the same view as the ball-and-stick diagrams in (a). (d) A 1-D channel viewed along the crystallographic b-axis, where a CO2 is ligated to Cu(II) site. Ball-and-stick diagrams of the single crystal structures of (e) MeOH-bound 1a at 173 K, (f) CO2-bound 1a at 195 K, and (g) CO2-bound 1a at 296 K.

1 has potential 1-D microporous channels made of cages aligned along the crystallographic b-axis (Fig. 2a and c). The shortest and the longest dimensions of the cage are ~3.5 and 5.5 Å, respectively, and the neck-like portal window of ~2.5 Å in diameter is formed between the cages (Figs 2c and S1). Each cage contains two methanol molecules. An approximate half of them in ~0.5 site occupancy are ligated to the two symmetry-related Cu(II) sites in the cage (Figs 2e and S2a) and the remaining lattice methanol molecules are statistically disordered in the vicinity of the ligated methanol molecules (Figs 2e and S2b).

The properly activated sample, 1a, was prepared by vacuuming (~10−2 torr) (MeOH)2@1a at 160 °C for 7 d (Figs S3–S7). Single crystals of the CO2-bound 1a ((CO2)0.8@1a-195K) were obtained by keeping single crystals of 1a in CO2 at ~1.5 bar and at ambient temperature for an hour, and then cooling down to 195 K. The structure analysis revealed that CO2 was ligated to unsaturated metal site using its Lewis basic oxygen atom in an angular η1-(OA) coordination mode with a 0.40(1) site occupancy factor (0.8 CO2 molecule per cage) (Figs 2f and S8). The Cu−OCO2 distance, 2.94(2) Å, is slightly longer than the Cu−OMeOH distance, 2.617(4) Å, of the bound MeOH in the as-synthesized crystal but still significantly shorter than the sum of their van der Waals radii sum (3.55 Å)14. The Cu−OCO2 distance is, much longer than the corresponding Ni-OCO2 bond distances in Ni-MOF-74 structure obtained from the PXRD experiment, 2.29(2) Å22, the corresponding Mg−OCO2 bond distances in Mg-MOF-74 structures obtained from the NPD experiments, from 2.24(3) Å to 2.39(6) Å31, but is comparable to that of Cu-MOF-74, 2.86(3) Å32. It is well-known that the Lewis acidic carbon atom of the CO2 molecule can interact with the Lewis basic nitrogen atom in the pore environment16,17,18,19,29. Similar Lewis acid-base interaction is also observed in the CO2-bound 1a. The Lewis acidic carbon atom (C1C) of the bound CO2 molecule is interacting with the two Lewis basic nitrogen atoms (N3) of two symmetry-related tz ligands. The distance between C1C and N3 (3.21(2) Å) is slightly shorter than their van der Waals radii sum (3.30 Å). The Cu2-O1C-C1C bond angle (124(2)°) is in the range those in Ni-MOF-74, Mg-MOF-74, and Cu-MOF-74 structures (from 117(2) to 144(2)°). The observed site occupancy factor of the ligated CO2 molecule, 0.40(1), is due to steric repulsion between the CO2 molecules bound to the symmetry-related Cu(II) sites in a cage. The interatomic distance between the symmetry-related ligated oxygen atoms of the bound CO2 molecules (2.647(2) Å) is much closer than their van der Waals radii sum (3.1 Å) (Fig. 2f). The steric repulsion between the CO2 molecules hinders simultaneous ligation of two CO2 molecules in the same cage. The geometry of the bound CO2 at 195 K is similar to that of a reported free CO2 structure. The C−O bond distances, 1.12(3) Å and 1.13(3) Å, in the bound CO2 structure are not distinguishable to that in the free CO2 structure, 1.155(1) Å33. The little variation in the C−O bond distance in the bound CO2 is due to the combined effect of two different interactions between the CO2 molecule and the framework. The CO2 molecule donates its σ electron to the metal center through the ligating oxygen atom but simultaneously accepts σ electron from the two Lewis basic nitrogen atoms of the tz ligands through the Lewis acidic carbon atom of the bound CO2. The O−C−O bond angle in the bound CO2 structure, 176(3)°, is also nearly linear as that in the free CO2 structure.

The single crystal of (CO2)0.26(H2O)0.15@1a-296K-5h (the single crystal of CO2@1a-195K stood at ambient condition for five hours) showed the bound CO2 molecule in the cage with reduced site occupancy, 0.13(2) (Fig. 2g). Though the CO2 molecule is still ligated to the metal center, the Cu−O bond distance of (CO2)0.26(H2O)0.15@1a-296K-5h at 296 K, 3.09(5) Å, is elongated by ~0.15 Å than that of (CO2)0.8@1a-195K at 195 K but is still slightly shorter than the van der Waals sum of Cu and O atoms. However, interestingly, the Lewis acidic carbon atom (C1C) of the bound CO2 molecule is no longer interacting with the Lewis basic nitrogen atom (N3) of the ligand. The distance between C1C and N3 (3.34(4) Å) is slightly longer than their van der Waals radii sum, 3.30 Å. The complete replacement of the bound CO2 molecules in the pore by the water molecules in air took 10 days at ambient condition (Figs S8 and S9).

The vibrational mode analysis of the CO2 molecule encapsulated in a cage

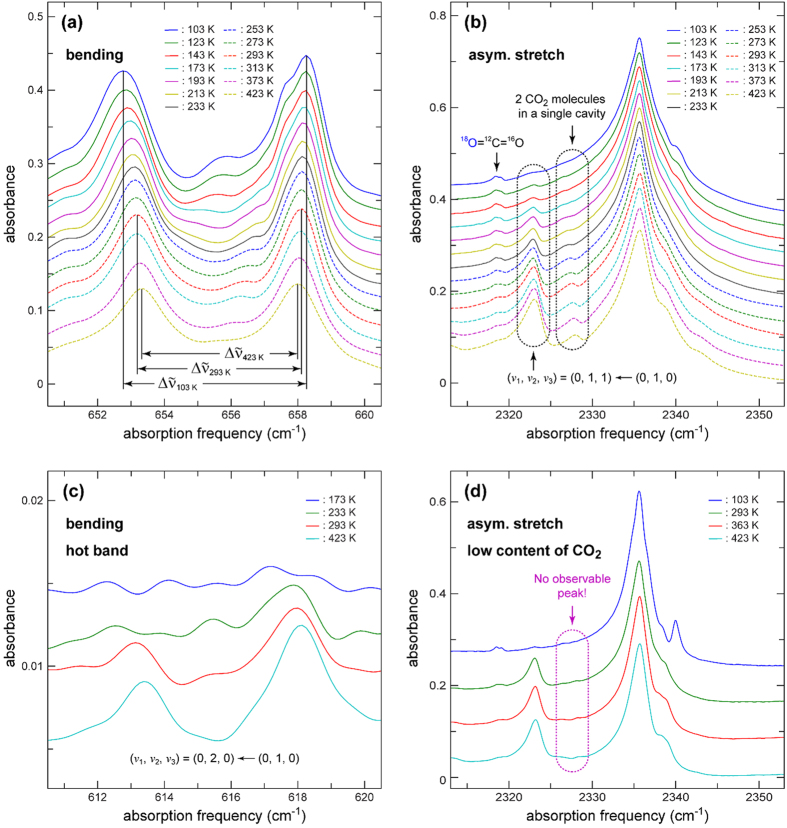

Figure 3 shows temperature-dependent infra-red (IR) spectra of the MOF, 1a, filled with 12CO2 molecules in the bending and asymmetric stretch regions (see Fig. S10 for whole-range spectra). In the IR spectra of the bending region given in Fig. 3a, two separate peaks are observed, which is distinctively different from the case of a free CO2 molecule where only a single bending peak appears because its two bending modes are degenerate. This observation suggests that the interaction between a CO2 molecule and 1a disturbs its bending motion to generate two separate peaks. The center frequency of the two peaks is also red-shifted by 11.7 cm−1 compared to the degenerate bending frequency of a free CO2 of 667.3 cm−1 34. Similar splitting of the bending modes and red-shift of the center frequency has been reported in the IR spectra of the CO2 bound in an η1-(OA) coordination mode in Ni-MOF-7410. The splitting of the two bending modes must be related to the binding energy of a CO2 molecule to the framework and a larger separation indicates stronger interaction between them. The separation between the two peaks decreases as the temperature increases from 5.49 cm−1 at 103 K to 4.92 and 4.67 cm−1, respectively, at 293 and 423 K. Provided that the binding energy is proportional to the separation, the binding energy at 293 and 423 K, respectively, decreases by 11 and 15% compared with that at 103 K. The CO2 molecule encapsulated in the cage is less strongly bound to the framework at elevated temperatures. These observations are in agreement with the temperature dependent crystal structures of CO2@1a. Though the bound CO2 structures themselves from the temperature dependent single crystal structure study are not as sensitive as the bending modes of the bound CO2 molecule, the temperature dependent interactions between the CO2 and the framework are in good agreement with the temperature dependent bending modes of the bound CO2 molecule. While the peak separation of the two symmetric bending modes of the bound CO2 molecule is temperature dependent, the center frequency is insensitive to temperature. Temperature insensitivity of the center frequency is due to the combined result of simultaneous weakening of both the sigma electron donation to the Cu(II) ion through the Lewis basic oxygen atom of the bound CO2 and the sigma electron acceptance from the nitrogen atoms of the tz ligands via the Lewis acidic carbon atom of the bound CO2 molecule.

Figure 3. Temperature- and CO2 concentration-dependent FTIR spectra of 1a filled with 12CO2.

(a) Spectra in the bending region of 12CO2. Δ 103 K (5.49 cm−1), Δ

103 K (5.49 cm−1), Δ 293 K (4.92 cm−1), and Δ

293 K (4.92 cm−1), and Δ 423 K (4.67 cm−1) represent the separation between the two peak maxima at 103, 293, and 423 K, respectively. Similar spectra are reported for 1a filled with 13CO2 in Fig. S11. (b) Spectra in the asymmetric stretch region of 12CO2. The peaks enclosed with rounded rectangles in the spectral region of ~2323 and ~2327 cm−1 represent a vibrational hot band (starting from the first excited state of the bending mode) and a peak originating from the existence of 2 CO2 molecules in a single cavity, respectively. (c) Spectra in the spectral region of v2 = 1 → v2 = 2 transition (hot band). (d) Spectra of 1a with low CO2 content in the spectral region of the asymmetric stretch. Note that the spectra in (a,b and c) were obtained from the same sample (high content of CO2), whereas the spectra in (d) were obtained from a different sample (low content of CO2).

423 K (4.67 cm−1) represent the separation between the two peak maxima at 103, 293, and 423 K, respectively. Similar spectra are reported for 1a filled with 13CO2 in Fig. S11. (b) Spectra in the asymmetric stretch region of 12CO2. The peaks enclosed with rounded rectangles in the spectral region of ~2323 and ~2327 cm−1 represent a vibrational hot band (starting from the first excited state of the bending mode) and a peak originating from the existence of 2 CO2 molecules in a single cavity, respectively. (c) Spectra in the spectral region of v2 = 1 → v2 = 2 transition (hot band). (d) Spectra of 1a with low CO2 content in the spectral region of the asymmetric stretch. Note that the spectra in (a,b and c) were obtained from the same sample (high content of CO2), whereas the spectra in (d) were obtained from a different sample (low content of CO2).

Figure 3b shows that the main asymmetric stretching band at ~2335 cm−1 with a FWHM of ~7 cm−1 is red-shifted by 14 cm−1 compared to the corresponding band of free 12CO2 at 2349 cm−1 33. The red-shift indicates that the σ electron donation through the Lewis basic oxygen atom of the bound CO2 to the Cu(II) center is slightly stronger than the σ electron acceptance through the carbon atom of the bound CO2 from the nitrogen atoms of the tz ligands. An asymmetric stretching band shift is not a good indicator of the binding strength of an encapsulated CO2 to a framework. It is a combined effect of electron donation and acceptance of the encapsulated CO2 to and from the framework. The encapsulated CO2 in the series of isostructural MOFs, M-MOF-74 (where, M = Ni(II), Mg(II), Zn(II), and Co(II)), showed different shifts of the asymmetric CO2 stretching band depending on metal ions even though the frameworks are isostructural35.

The side bands at the high-frequency side are likely to originate from slightly different local structures of CO2 inside the cage. At the lower-frequency side of the main band, two peaks, each of which is enclosed with a rounded rectangle, are observed. The temperature dependent peak at ~2323 cm−1 was assigned as a vibrational hot band coming from the transition, (ν1, ν2, ν3) = (0, 1, 0) → (0, 2, 0)36. The assignment is further clarified by the hot-band spectra in the bending region shown in Fig. 3c, where the magnitude of the peaks follows the Boltzmann distribution. However, the peak at ~2327 cm−1, which shows similar temperature dependence as the peak at ~2323 cm−1, was assigned to be a peak arising from CO2 double occupancy in a single cage (two CO2 molecules in a single cage interacting to each other). Figure 3d shows the asymmetric stretch region of another sample that contains less amount of CO2 by a factor of 3. The integrated areas of the peaks in the spectra of the low CO2 content sample are about 1/3 of those of their corresponding spectra (Fig. S12). The double-occupancy peak is hardly observable at 2327 cm−1 indicating that the integrated area of the peak is not linearly proportional to CO2 concentration and the peak must be from the double occupancy. In the spectra of the low CO2 content sample, the peaks are narrower than their corresponding ones in the high-content spectra. This observation suggests that the skeleton of 1a is rather flexible and the structural distribution of the encapsulated CO2 becomes more inhomogeneous with increase in CO2 content37.

The observation that the magnitude of the double-occupancy peak increases as the temperature increases (Fig. 3b) should also be paid attention to. A single CO2 molecule in a single cage is preferred at lower temperature under lower concentration of CO2. The steric repulsion between the CO2 molecules ligated to the two symmetry-related metal sites in the same cage at low temperature is responsible for this single occupancy. Two CO2 molecules in a single cage are allowed at high temperature under higher CO2 content. The reduced restraint on the position of the weakly interacting CO2 molecule in the cage at high temperature allows two CO2 molecules in a single cage. The existence of the double-occupancy peak helps us to understand the process of CO2 filling into the 1-D microporous channels, made of small cages interlinked with small neck-like portal windows. Not only a hopping process of a CO2 molecule into an empty cage but also a filling process of a second CO2 molecule into the cage with an encapsulated CO2 are operating.

CO2 sorption behaviors

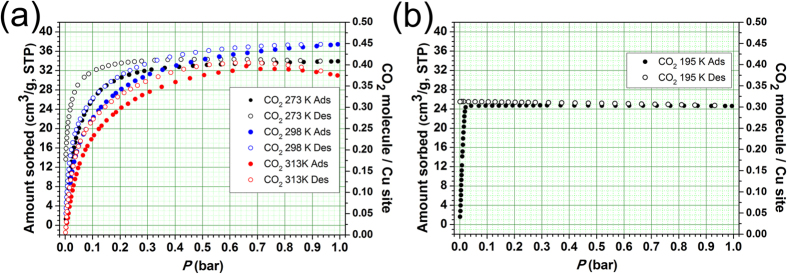

Even though 1a had microporous 1-D channel, it does not show any N2 (at 77 K and 308 K), H2 (at 77 K) and CH4 (at 195 K and 308 K) adsorptions (Fig. S13). However, 1a shows reversible CO2 uptake at 273 K even though the kinetic diameter of CO2 (3.3 Å) is much larger than the dimension of the portal window and the isotherms are of a typical type I (Fig. 4a). The large quadruple moment of CO2 might be responsible for such uptake behavior. The CO2 molecule can interact with the framework strong enough to induce the portal dimension of the 1-D microporous channels large enough for the reversible CO2 adsorption and desorption. The total CO2 uptake amount of 1a at 273 K and 1 bar, 33.9 cm3/g, corresponds to 0.82 CO2 molecules per cage (or 0.41 CO2 molecules per unsaturated Cu(II) center). The CO2 sorption isotherms of 1a at 298 K are also reversible type I isotherms and the total CO2 uptake amount at ~1 bar is 37.4 cm3/g, which is slightly larger than the CO2 uptake amount at 273 K and ~1 bar. The increased CO2 uptake amount at the higher temperature is due to increased double occupancy of CO2 molecules in a single cage and subsequent pore filling up to the cages located at the inner parts of the microporous 1-D channels. The total CO2 uptake amount at 313 K and ~1 bar, 31.3 cm3/g, is slightly smaller than that at 298 K. The reduced CO2 uptake amount is due to decreased CO2-framework interaction at the higher temperature. The adsorption enthalpy (−ΔHads) of CO2 on 1a calculated using the adsorption isotherms at 298 K and 313 K is −32– −25 kJ/mol (Fig. S14), which will be the lower bound because the isotherms obtained are not in the true equilibrium condition due to slow adsorption kinetics of CO2. The adsorption enthalpy (−ΔHads) of CO2 estimated using desorption isotherms at 298 K and 313 K is −41– −35 kJ/mol, which is comparable to the CO2 adsorption enthalpy on Mg-MOF-74, ~40 kJ/mol22,32, but is much larger than that on Cu-MOF-74, ~22.1 kJ/mol32.

Figure 4. Gas sorption of 1a.

(a) Reversible CO2 adsorption and desorption isotherms at 273 K, 298 K, and 313 K. (b) Irreversible CO2 adsorption and desorption isotherms at 195 K.

Interestingly, the CO2 sorption on 1a at 195 K is irreversible (Fig. 4b). The CO2 adsorption isotherm at 195 K shows steep rise at very low pressure. The adsorption reaches to its maximum amount, 24.3 cm3/g, at 0.022 bar. The amount of adsorbed CO2 corresponds to ~0.60 CO2 molecule per cage (or ~0.30 CO2 molecule per unsaturated metal site), which is much smaller than the expected maximum amount, one CO2 molecule per cage (or 0.5 CO2 molecule per unsaturated metal site). Significant portions of the inner cages in the 1-D porous channel may not be accessible for CO2 molecule because the channels are already blocked by the CO2 molecules bound strongly to the framework as shown in Fig. 2d. There is no indication of CO2 desorption even at 0.0015 bar.

At high temperature, not only hopping process of a CO2 molecule into an empty cage but also filling process of a second CO2 molecule into the cage with an encapsulated CO2 molecule are allowed so that even most of the empty inner cages of the 1-D channels could be occupied with CO2 molecules and the CO2 molecules in the inner cages the 1-D channels can also be emptied via a reverse process. However, at low temperature, the filling of a second CO2 molecule into the cage with an encapsulated CO2 molecule is severely hindered because the CO2 molecule bound strongly at the open metal center does not allow the second CO2 molecule into the same cage. At low temperature, the main pore filling is via hopping process so that the maximum amount of CO2 captured in the 1-D channels is significantly smaller than the expected maximum amount of CO2. When multiple consecutive cages in a 1-D channel are filled with CO2 molecules, desorption of CO2 is also severely hindered, which is the cause of the irreversible CO2 sorption behavior of 1a at 195 K.

Conclusions

Although each cage contains two unsaturated Cu(II) sites and the cage size is large enough for two CO2 molecules, the CO2 uptake amount is only ~0.9 CO2 molecule per cage at 298 K and 1 bar, which is due to the steric repulsion between the two bound CO2 molecules in the cage. Temperature dependent single crystal structure analyses revealed that the interaction between the bound CO2 molecule and the framework of the MOF is temperature-dependent. As temperature increases, both the CO2 coordination to the unsaturated Cu(II) center and the Lewis acid−base interaction between the carbon atom of the CO2 molecule and the nitrogen atom of the ligand are simultaneously weakened.

The red-shifted vibrational peaks of the bound CO2 molecule indicate that the electron donation to the metal center through the oxygen atom of the CO2 molecule is slightly larger than the electron acceptance from the nitrogen atom of the ligand through the carbon atom of the CO2 molecule. The temperature dependent separation of the two bending peaks also supports the temperature dependent interaction between the CO2 molecule and the framework of the MOF. As temperature increases, the separation of the bending peaks decreases. The observation tells that the CO2–framework interaction decreases as the temperature increases as observed in the temperature dependent structure analyses of a single crystal of CO2@1a.

The reversible CO2 uptakes on 1a were observed at 298 and 313 K, respectively, even though the portal dimension of the cage aligned along the microporous 1-D channel is smaller than the kinetic diameter of CO2 molecule. The CO2 uptake amount per unsaturated Cu(II) center at 298 K, 1 bar is 0.45 molecule, which is only slightly smaller than the probable maximum value, 0.5. On the other hand, the irreversible CO2 uptake was observed at 195 K and the CO2 uptake amount per unsaturated Cu(II) center is only 0.30 molecule, which is much smaller than the expected value, 0.5. The decreased uptake amount at the lower temperature is due to the strongly interacting CO2 molecules in the cages aligned along the microporous 1-D channel hindering the other CO2 molecules to access the available inner cages in the 1-D channel. The different uptake behaviour at different temperature is related to both the small portal dimension of the cages aligned along the 1-D channel and the different strength of CO2−framework interaction in the cage. The reversible CO2 uptakes were observed at the higher temperature since the CO2 molecule interacting weakly with the framework could have proper orientation for the escape from the cavity through the small portal of the cages. However, the irreversible CO2 uptake was observed at the lower temperature since the CO2 molecule interacting strongly enough with the metal center in the cage could not have proper orientation for the escape from the cavity through the small portal.

Methods

Synthesis of the MOF, Cu3Cl2(tz)4(MeOH)2, 1

A 27.3 mg amount of CuCl2 (0.203 mmol) was dissolved in 4 mL MeOH in a 10 mL vial, and then 0.90 mL 0.45 M tetrazole (tz) acetonitrile solution (0.41 mmol) was added into the solution. The Teflon-sealed vial was heated to 70 °C for 7 days and then slowly cooled down to ambient temperature. The block-shaped blue crystals obtained were washed using 10 mL fresh methanol and filtered.

IR spectroscopy

The samples were in the form of a KBr pellet of a ~200-μm thickness and a 13-mm diameter. The samples were located in a cell composed of two circular KBr windows of a 25-mm diameter. The windows were separated by a 200-μm thick spacer with 25 and 20 mm outer and inner diameters, respectively. FTIR spectra were recorded by a Varian 7000e FTIR spectrometer. The samples with KBr windows were placed in a home-made oxygen-free high thermal conductivity (OFHC) copper cell, and the temperature of the samples was controlled and maintained in a variable temperature cell holder (GS21525, Specac, UK). Details of the temperature-controllable cell assembly have been reported elsewhere38.

Gas sorption measurements

All gas sorption isotherms were measured using a BELSORP-max (BEL Japan, Inc.) with a standard volumetric technique.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kim, D. et al. Temperature dependent CO2 behavior in microporous 1-D channels of a metal-organic framework with multiple interaction sites. Sci. Rep. 7, 41447; doi: 10.1038/srep41447 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NRF (2015R1A2A1A15053104, 2015R1D1A1A01056579, 2011-0015061 and 2016R1A5A1009405) through the National Research Foundation of Korea. The authors acknowledge PAL for beam line use (2014-2st-2D-018) and fs-THz beamline for the vibrational analysis experiments.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions M.S.L. and D.K. designed the research. D.K. synthesized the MOFs, solved the X-ray crystal structures and performed the gas sorption analyses. J.P. and Y.S.K. performed the vibrational analysis experiments. M.S.L. and Y.S.K. wrote the manuscript. All the authors analysed the data, and reviewed and contributed to the manuscript.

References

- Creamer A. E. & Gao B. In Carbon dioxide capture: an effective way to combat global warming, Ed. Sharma, S. K. (Springer, Switzerland 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa J. D. et al. Advances in CO2 capture technology—The U.S. department of energy’s carbon sequestration program. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2, 9 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Benson E. E. et al. Electrocatalytic and homogeneous approaches to conversion of CO2 to liquid fuels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 89 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokoja M. et al. Transformation of carbon dioxide with homogeneous transition-metal catalysts: A Molecular Solution to a Global Challenge? Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 50, 8510 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omae I. Recent developments in carbon dioxide utilization for the production of organic chemicals. Coord. Chem. Rev. 256, 1384 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Schoedel A. et al. The role of metal–organic frameworks in a carbon-neutral energy cycle. Nature Energy 1, 16034 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Sumida K. et al. Carbon dioxide capture in metal−organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 112, 724 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald T. M. Cooperative insertion of CO2 in diamine-appended metal−organic frameworks. Nature 519, 303 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A. et al. Direct air capture of CO2 by physisorbent materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 14372 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.-Q. et al. Visible-light photoreduction of CO2 in a metal−organic framework: boosting electron−hole separation via electron trap states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 13440 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darensbourg D. J. et al. Sequestering CO2 for short-term storage in MOFs: copolymer synthesis with oxiranes. ACS Catal. 4, 1511 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z.-R. et al. Polar group and defect engineering in a metal–organic framework: synergistic promotion of carbon dioxide sorption and conversion. ChemSusChem 8, 878 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Rodriguez I. et al. A linear, O-coordinated η1-CO2 bound to uranium. Science 305, 1757 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornia A. et al. Manganese(III) formate: a three-dimensional framework that traps carbon dioxide molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38, 1780 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maji T. K. et al. Guest-induced asymmetry in a metal–organic porous solid with reversible single-crystal-to-single-crystal structural transformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 17152 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.-P. & Chen X.-M. Optimized acetylene/carbon dioxide sorption in a dynamic porous crystal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 5516 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidhyanathan R. et al. Direct observation and quantification of CO2 binding within an amine-functionalized nanoporous solid. Science 330, 650 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.-B. et al. An ionic porous coordination framework exhibiting high CO2 affinity and CO2/CH4 selectivity. Chem. Commun. 47, 926 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao P.-Q. et al. Strong and dynamic CO2 sorption in a flexible porous framework possessing guest chelating claws. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17380 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wriedt M. et al. Low-energy selective capture of carbon dioxide by a pre-designed elastic single-molecule trap. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 9804 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang S. et al. Microporous metal–organic framework with potential for carbon dioxide capture at ambient conditions. Nat. Commun. 3, 954 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzel P. D. C. et al. Adsorption properties and structure of CO2 adsorbed on open coordination sites of metal–organic framework Ni2(dhtp) from gas adsorption, IR spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction. Chem. Commun. 5125 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano M. et al. Activation of coordinated carbon dioxide in Fe(CO2)(depe)2 by group 14 electrophiles. Organometallics 16, 4206 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Fu P.-F. et al. Carbon dioxide complexes via aerobic oxidation of transition metal carbonyls. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114, 6579 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H. et al. Crystal structure of cis-(carbon monoxide)(η1-carbon dioxide) bis(2,2′-bipyridyl)ruthenium, an active species in catalytic COP reduction affording CO and HCOO−. Organometallics 11, 1450 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Nandi G. & Goldberg I. Fixation of CO2 in bi-layered coordination networks of zinc tetra(4-carboxyphenyl)porphyrin with multi-component [Pr2Na3(NO3)(H2O)3] connectors. Chem. Commun. 50, 13612 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. A. et al. Direct x-ray observation of trapped CO2 in a predesigned porphyrinic metal–organic framework. Chem. — Eur. J. 20, 7632 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H. et al. Adsorption sites and binding nature of CO2 in prototypical metal−organic frameworks: a combined neutron diffraction and first-principles study. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 1946 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Poloni R. et al. CO2 capture by metal−organic frameworks with van der Waals density functionals. J. Phys. Chem. A 116, 4957 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keeffe M. et al. The reticular chemistry structure resource (RCSR) database of, and symbols for, crystal Nets. Accts. Chem. Res. 41, 1782 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queen W. L. et al. Site-specific CO2 adsorption and zero thermal expansion in an anisotropic pore network. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 24915 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Queen W. L. et al. Comprehensive study of carbon dioxide adsorption in the metal–organic frameworks M2(dobdc) (M = Mg, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn). Chem. Sci. 5, 4569 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Simon A. & Peters K. Single-crystal refinement of the structure of carbon dioxide. Acta Cryst B. 36, 2750 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Dennison D. M. The infra-red spectra of polyatomic molecules. Part II. Rev. Mod. Phys. 12, 175 (1940). [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y. et al. Analyzing the frequency shift of physiadsorbed CO2 in metal organic framework materials. Phys. Rev. B 85, 064302 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Giammanco C. H. et al. Coupling of carbon dioxide atretch and bend vibrations reveals thermal population dynamics in an ionic liquid. J. Phys. Chem. B 120, 549 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida J. et al. Structural dynamics inside a functionalized metal–organic framework probed by ultrafast 2D IR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 18442 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D.-H. et al. Dielectric relaxation change of water upon phase transition of a lipid bilayer probed by terahertz time domain spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 175101 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.