Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases due to atherosclerosis are the leading cause of death globally. We aimed to investigate the potentially altered gene and pathway expression in advanced peripheral atherosclerotic plaques in comparison to healthy control arteries. Gene expression analysis was performed (Illumina HumanHT-12 version 3 Expression BeadChip) for 68 advanced atherosclerotic plaques (15 aortic, 29 carotid and 24 femoral plaques) and 28 controls (left internal thoracic artery (LITA)) from Tampere Vascular Study. Dysregulation of individual genes was compared to healthy controls and between plaques from different arterial beds and Ingenuity pathway analysis was conducted on genes with a fold change (FC) > ±1.5 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. 787 genes were significantly differentially expressed in atherosclerotic plaques. The most up-regulated genes were osteopontin and multiple MMPs, and the most down-regulated were cell death-inducing DFFA-like effector C and A (CIDEC, CIDEA) and apolipoprotein D (FC > 20). 156 pathways were differentially expressed in atherosclerotic plaques, mostly inflammation-related, especially related with leukocyte trafficking and signaling. In artery specific plaque analysis 50.4% of canonical pathways and 41.2% GO terms differentially expressed were in common for all three arterial beds. Our results confirm the inflammatory nature of advanced atherosclerosis and show novel pathway differences between different arterial beds.

Atherosclerosis, the most common cause for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) is a complex disease affecting millions of people around the world1. Genetic factors, environment, lifestyle choices and the various interactions between these affect the development of atherosclerotic plaques and modify individuals risk for adverse CVD events. Development of atherosclerotic plaque modifies the arterial wall through many metabolic pathways with inflammation and deposition of lipids being the most crucial processes involved. There is great variability in the development of this disease between individuals and even though atherosclerosis has a systemic nature, there are differences in gene-expression in plaques occurring in different arterial beds2. Also the prevalence of calcified or unstable plaques often varies according to vascular region3 and the on-going processes in a plaque differ greatly according to the stage of the plaque4.

Atherosclerosis begins with microscopic changes in the arterial wall. Accumulation of lipoproteins5 attracts inflammatory cells that begin to invade the intima6,7. As the disease progresses the arterial wall gathers more lipids and inflammatory cells (mainly T-cells and monocytes) and a visible fatty streak forms. Although the formation of a fatty streak is seen as a reversible event, it can be followed by the formation of fibrotic tissue leading to the stabilization of the plaque. The vascular smooth muscle cells begin to replicate contributing to the formation of the atheroma and the blood flow in the artery is impaired7,8. The plaque can also gather calcium and form a hard calcified plaque. The rupture or erosion of the the atherosclerotic plaque may result in a local thrombosis or release of distant thromboemboli, which both can have lethal consequences depending on the location of the plaque7,9.

Differentially expressed genes have been shown in various studies designed to specifically demonstrate the regulation of selected single genes in atherosclerosis. These studies have mostly been conducted in vivo, focusing on up-regulating or down-regulating selected genes, in order to find out their effect on the development and progression of atherosclerosis. Results show that changes in the expressions of target genes can also lead into the suppression of some atheroprotective qualities10,11. Previous studies have shown the inflammatory nature of atherosclerosis12, demonstrating the roles of different leukocytes present in atherosclerotic plaques13. Degradation and remodeling of the extracellular matrix14 and changes in the arterial wall15 are the most important processes related with atherosclerosis. Therefore, instead of single gene analysis to reveal the pathways – an unbiased whole genome wide pathway analyses against most recently updated gene-pathway databases are needed16,17,18. So far, a lot of data has been collected in murine and porcine models. Nevertheless, research on humans and human tissues is needed as genetically unaltered mice do not spontaneously develop atherosclerosis and the time frame and contributing risk factors differ greatly in animal models.

In ongoing Tampere Vascular Study (TVS)2 we aim to detect specific genes as well as pathways consisting of a set of genes differentially expressed in advanced atherosclerotic plaques compared to healthy non-atherosclerotic arteries (referred simply as differentially expressed). In our previous pilot work with 24 samples (6 controls and 18 cases)2 we established genes and pathways differentially expressed in atherosclerosis, including some MMPs and ApoC1 and upregulated proinflammatory pathways. In this study, with a substantially larger set of samples, and using novel Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) for the pathway analysis we aimed to further analyze the pathways and genes differentially expressed in peripheral advanced atherosclerotic plaques in humans. We also aimed to find possible differences between gene sets specific for plaques formed in certain arterial beds in different parts of arterial network. This larger sample set has been utilized in analyzing individual genes and their role in atherosclerotic plaques in hypothesis based studies19,20,21,22, and this study was performed to create a more comprehensive description of different expression of genes and pathways in atherosclerosis.

Materials and Methods

Tampere Vascular Study

The atherosclerotic vascular samples used in this study were obtained from patients subjected to carotid (N = 29) and femoral (N = 24) endarterectomy or an abdominal aortic bypass (N = 15) procedure (i.e., aortobifemoral bypass) due to occlusive atherosclerosis. The control vessel, left internal thoracic artery (LITA) (N = 28) samples were obtained during coronary artery bypass surgery22,23,24,25,26,27. Each sample was obtained from a different individual. All open vascular surgical procedures were performed at the Division of Vascular Surgery and the Heart Center at Tampere University Hospital between 2006 and 200927. The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Pirkanmaa Hospital District and clinical investigation followed the principles of Helsinki declaration. Informed consent was acquired from patients enrolled in this study. In the present work the severity of atherosclerotic lesions in artery wall was histologically classified according to the American Heart Association classification (AHA classification I-VI)28. Demographics of the study population are presented in Supplementary File 1.

RNA isolation and genome wide expression analysis

The fresh tissue samples were soaked in RNALater solution (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX, USA) and isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and the RNAEasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The RNA quality as well as concentration was evaluated spectrophotometrically (BioPhotometer, Eppendorf, Wesseling-Berzdorf, Germany). The RNA isolation protocol was validated with Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit and the RNA integrity number (RIN) and the shape of the electropherogram were evaluated. In all the samples with successful gene expression profiling the 260/280 ratio was between 1.94–2.23. Over 23,000 known and candidate genes were analyzed with Illumina HumanHT-12 version 3 Expression BeadChip (Illumina Inc.), according to manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Briefly, 200 ng aliquots of total RNA from each sample were amplified to cDNA using the Ambion’s Illumina RNA Amplification kit according to the instructions (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX, USA). Samples of cRNA (1500 ng) were hybridized to Illumina’s Expression BeadChip arrays (Illumina). Hybridized biotinylated cRNA was detected with 1 μg/ml Cyanine3-streptavidine (Amersham Biosciences, Pistacataway, NJ, USA). BeadChips were scanned with the Illumina BeadArray Reader2. The accuracy of this array has been previously tested in our TVS validation study where the results of 192 differentially expressed genes were verified by RT-PCR23. The correlation of expression measurements between GWE and RT-PCR methods was good (r = 0.87, y = 0.151 + 0.586x), and the Bland-Altman plot showed that the FCs were in agreement with these two methods, although for highly up- or down-regulated transcripts, GWE yielding lower absolute FC values than in LDA23.

Microarray array data analysis and multiple testing corrections

After background subtraction, raw intensity data were exported using the Illumina GenomeStudio software. Raw expression data were imported into R version 3.1.1 (http://www.r-project.org/), log2 transformed and normalized by the locally estimated scatterplot smoothing normalization method implemented in the R/Bioconductor package Lumi (www.bioconductor.org). Locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) normalization for the data was selected because it gives the best accuracy in comparison with quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction data for artery samples23. Data quality control criteria included detection of outlier arrays based on the low number of robustly expressed genes and hierarchical clustering. Artery samples (n = 96: 68 plaque, 28 LITA) fulfilled all data quality control criteria, whilst 6 samples were discarded. To estimate fold changes between groups, we calculated differences between medians (in log2 scale) and then back transformed the log ratios to fold changes. To ease the interpretation, we replaced fold-change values that are <1 by the negative of its inverse. Statistical significance of differences in gene expression was assessed using the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test and the log-transformed data. Pathway analysis of the expression data was done with QIAGEN’s Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, QIAGEN Redwood City, www.qiagen.com/ingenuity) for genes with FC ± 1.5 and FDR < 0.05. Pathways with FDR < 0.05 (Benjamini-Hochberg method29) were found to be significantly differentially expressed. The GO-terms were analysed using GOrilla online tool30. The Venn diagrams were done using Venny 2.1.0 online tool31.

Results

Overall gene expression differences between atherosclerotic and atherosclerosis free arteries

787 of genes were significantly differentially expressed (FC > ±3.0, FDR < 0.05) in atherosclerotic plaques in comparison to healthy control arteries (Supplementary File 2). Table 1 lists the most significantly differentially expressed genes between all atherosclerotic plaque samples versus atherosclerosis free control arteries (LITAs) (All vs. LITA, up- or down-regulated, FC ≥ 15, FDR < 0.05) and the corresponding FC and p-values obtained from comparisons between different atherosclerotic plaque groups (aortic, carotid, femoral) and LITAs. The single most up-regulated gene was osteopontin (SPP1/secreted phophoprotein-1) (FC = 121.9 in all atherosclerotic plaques in comparison to controls). It was highly up-regulated in all analyzed atherosclerotic arterial beds (FC > 100) and it was the most differentially expressed gene in femoral and carotid plaques (Supplementary Files 1 and 2).

Table 1. The most significantly differentially expressed genes in All atherosclerotic plaques versus atherosclerosis free control arteries (LITA), (FC ≥ ± 15 and FDR < 0.05) and the corresponding FC and p-values from comparisons between atherosclerotic plaques from different arterial beds (abdominal aorta, carotid, femoral) compared to LITA.

| Gene symbol | ACCESSION | All vs. LITA |

Aorta vs. LITA |

Carotid vs. LITA | Femoralis vs LITA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC | P-value | FC | p-value | FC | p-value | FC | p-value | ||

| SPP1 | NM_001040058.1 | 121.9 | 1.82*10−13 | 104.3 | 2.73*10−8 | 135.7 | 1.19*10−15 | 105.4 | 3.16*10−14 |

| SPP1 | NM_000582.2 | 109.1 | 1.82*10−13 | 90.9 | 2.73*10−8 | 113.9 | 1.19*10−15 | 99.9 | 3.16*10−14 |

| MMP12 | NM_002426.2 | 88.9 | 1.82*10−13 | 72.4 | 2.73*10−8 | 124.9 | 1.19*10−15 | 68.3 | 3.16*10−14 |

| MMP9 | NM_004994.2 | 76.1 | 1.82*10−13 | 32.0 | 2.73*10−8 | 98.8 | 1.19*10−15 | 76.9 | 3.16*10−14 |

| CIDEC | NM_022094.2 | −61.2 | 2.91*10−11 | −17.0 | 2.00*10−3 | −90.4 | 1.19*10−15 | −50.1 | 3.71*10−10 |

| KIAA1881 | XM_001130790.1 | −60.1 | 9.97*10−12 | −17.7 | 2.73*10−8 | −80.1 | 1.19*10−15 | −50.9 | 6.60*10−11 |

| LOC642113 | XM_936253.1 | 53.3 | 5.44*10−12 | 135.0 | 2.91*10−8 | 36.1 | 8.72*10−12 | 38.7 | 3.71*10−10 |

| MMP7 | NM_002423.3 | 52.5 | 2.21*10−13 | 17.8 | 3.93*10−8 | 91.8 | 1.19*10−15 | 36.2 | 3.16*10−14 |

| LOC647450 | XM_936518.1 | 52.4 | 5.12*10−12 | 153.5 | 2.91*10−8 | 47.6 | 8.72*10−12 | 32.5 | 2.94*10−10 |

| LOC652493 | XM_941953.1 | 52.1 | 3.55*10−12 | 127.7 | 2.91*10−8 | 45.2 | 4.17*10−12 | 32.1 | 1.82*10−10 |

| LOC652694 | XM_942302.1 | 47.2 | 3.14*10−12 | 129.4 | 2.14*10−8 | 46.0 | 2.48*10−12 | 22.2 | 1.43*10−10 |

| MMP12 | NM_002426.2 | 47.1 | 7.00*10−13 | 72.4 | 2.73*10−8 | 63.2 | 1.19*10−15 | 25.5 | 1.43*10−10 |

| APOD | NM_001647.2 | −39.7 | 1.24*10−10 | −1.4 | 3.76*10−2 | −68.1 | 1.19*10−15 | −43.9 | 3.16*10−14 |

| APOC1 | NM_001645.3 | 36.2 | 2.21*10−13 | 30.3 | 9.94*10−11 | 53.2 | 2.38*10−15 | 32.8 | 6.33*10−14 |

| PLA2G7 | NM_005084.2 | 29.9 | 2.21*10−13 | 12.5 | 5.97*10−10 | 43.6 | 1.19*10−15 | 28.0 | 3.16*10−14 |

| MMP7 | NM_002423.3 | 28.3 | 2.21*10−13 | 17.8 | 1.99*10−10 | 54.6 | 1.19*10−15 | 21.2 | 3.16*10−14 |

| KIAA1199 | NM_018689.1 | 25.5 | 1.82*10−13 | 31.0 | 4.97*10−11 | 26.5 | 1.19*10−15 | 19.5 | 3.16*10−14 |

| CIDEA | NM_001279.2 | −24.5 | 6.22*10−11 | −17.9 | 5.42*10−5 | −30.4 | 8.13*10−13 | −23.4 | 4.46*10−8 |

| ADAMDEC1 | NM_014479.2 | 24.2 | 1.82*10−13 | 26.1 | 4.97*10−11 | 28.5 | 1.19*10−15 | 15.0 | 3.16*10−14 |

| SCARA5 | NM_173833.4 | −22.8 | 6.16*10−13 | −3.3 | 1.08*10−6 | −27.0 | 1.19*10−15 | −23.8 | 3.16*10−14 |

| ACP5 | NM_001611.2 | 22.6 | 4.78*10−13 | 7.4 | 3.40*10−8 | 31.4 | 1.19*10−15 | 32.0 | 3.16*10−14 |

| IGLL1 | NM_020070.2 | 20.0 | 7.83*10−12 | 38.1 | 1.99*10−10 | 19.2 | 1.39*10−11 | 16.0 | 1.70*10−9 |

| LOC652102 | XM_941434.1 | 19.0 | 5.23*10−11 | 58.9 | 4.97*10−11 | 16.6 | 2.53*10−10 | 11.9 | 7.40*10−8 |

| APOE | NM_000041.2 | 17.6 | 7.45*10−13 | 15.8 | 1.34*10−7 | 27.7 | 2.38*10−15 | 16.4 | 3.16*10−14 |

| PLIN | NM_002666.3 | −17.3 | 5.87*10−11 | −12.9 | 4.66*10−5 | −19.0 | 1.44*10−12 | −18.5 | 1.70*10−9 |

| ACTA1 | NM_001100.3 | −16.3 | 7.40*10−11 | −9.3 | 7.02*10−7 | −19.6 | 2.26*10−14 | −9.2 | 3.86*10−7 |

| RGS1 | NM_002922.3 | 15.8 | 6.57*10−13 | 23.9 | 4.97*10−11 | 12.0 | 8.13*10−13 | 12.6 | 3.80*10−13 |

| OLR1 | NM_002543.3 | 15.8 | 3.70*10−13 | 20.6 | 5.97*10−10 | 15.4 | 5.35*10−14 | 17.1 | 1.27*10−13 |

| MYOC | NM_000261.1 | −15.2 | 3.05*10−13 | −11.1 | 2.24*10−9 | −17.8 | 1.19*10−15 | −10.9 | 6.33*10−14 |

aAbbreviations: FC = fold changes (FC); FDR = False discovery rate; LITA = left internal thoracic artery.

Many of the most up-regulated genes are previously known inflammatory genes, such as CD4, CD28 and chemokines and chemokine receptor genes. Other significantly up-regulated gene families are the MMPs (MMP7, MMP9 and MMP12, FC > 28 for all when comparing all atherosclerotic plaques to controls, Table 1). In addition, several gene families associated with lipid transport were the most differentially expressed ones in atherosclerotic plaques (Table 1, Supplementary File 2). Apolipoprotein-D (ApoD) was down-regulated in all the studied arterial beds, whilst ApoE and ApoC1 were both significantly up-regulated in atherosclerotic plaques. ApoC1 was especially up-regulated in carotid plaques (FC = 53.2). In addition, cell death-inducing DFFA-like effector C and A (CIDEC, CIDEA) were significantly down-regulated in atherosclerotic plaques in comparison to control LITA. CIDEC and CIDEA were down-regulated in the plaques from all the studied arterial beds but there were large differences in the magnitude of the down-regulation (Table 1, Supplementary File 2).

Gene expression differences between plaques derived from different arterial beds

We also found significant differences in the gene expression patterns between plaques taken from different types of arteries from different vascular regions. Most significant differences were seen between plaques from aortic and carotid arteries (FC > 5, FDR < 0.05) (Table 2). Especially ApoD and chemokine ligand 14, CXCL14, genes were down-regulated when comparing aortic to carotid artery plaque. Twenty-two genes were differentially expressed when comparing plaques from femoral artery to those from aorta whilst the plaques from carotid and femoral artery presented the most similar gene expression patterns (Table 2). The most differentially expressed genes between different arterial plaques (FC > 5.0, FDR < 0.05) are listed in Table 2 and more completely in Supplementary File 3.

Table 2. The most significantly differentially expressed (FC ≥ ± 5, FDR < 0.05) genes between atherosclerotic plaques from plaques from different arterial beds (abdominal aorta, carotid, femoral).

| SYMBOL | ACCESSION | FC | P | FDR | SYMBOL | ACCESSION | FC | P | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aorta vs carotid | Carotid vs femoral | ||||||||

| APOD | NM_001647.2 | 43.4 | 2.87*10−7 | 7.15*10−5 | HOXC6 | NM_004503.3 | −17.5 | 2.57*10−15 | 3.41*10−11 |

| CXCL14 | NM_004887.3 | 22.3 | 1.04*10−10 | 2.15*10−7 | AK123741 | −8.9 | 2.57*10−15 | 3.41*10−11 | |

| HOXC6 | NM_004503.3 | 16.2 | 8.70*10−12 | 8.98*10−8 | MMP13 | NM_002427.2 | −7.5 | 3.77*10−9 | 3.33*10−6 |

| PLA2G2A | NM_000300.2 | 16.1 | 4.42*10−9 | 3.26*10−6 | HOXC8 | NM_022658.3 | −6.7 | 2.57*10−15 | 3.41*10−11 |

| PI16 | NM_153370.2 | 14.2 | 7.95*10−9 | 5.02*10−6 | LMO3 | NM_018640.3 | 6.5 | 1.13*10−9 | 1.16*10−6 |

| SOST | NM_025237.2 | −10.5 | 3.52*10−7 | 8.23*10−5 | HOXA5 | NM_019102.2 | −6.2 | 2.57*10−15 | 3.41*10−11 |

| IL6 | NM_000600.1 | 9.7 | 1.65*10−10 | 2.74*10−7 | PITX1 | NM_002653.3 | −6.0 | 4.88*10−14 | 1.89*10−10 |

| RASD1 | NM_016084.3 | 9.0 | 7.95*10−9 | 5.02*10−6 | HOXC4 | NM_014620.4 | −5.8 | 2.57*10−15 | 3.41*10−11 |

| LOC653879 | XM_936226.1 | 8.6 | 7.66*10−7 | 1.46*10−4 | HOXA9 | NM_152739.3 | −5.7 | 2.57*10−15 | 3.41*10−11 |

| THBS4 | NM_003248.3 | 8.6 | 2.61*10−10 | 3.62*10−7 | SFRP1 | NM_003012.3 | 5.2 | 1.13*10−5 | 1.09*10−3 |

| HOXA5 | NM_019102.2 | 8.4 | 8.70*10−12 | 8.98*10−8 | Femoral vs aorta | ||||

| C3 | NM_000064.1 | 7.3 | 1.53*10−7 | 4.80*10−5 | APOD | NM_001647.2 | −27.8 | 2.85*10−5 | 9.15*10−3 |

| DARC | NM_002036.2 | 7.2 | 1.33*10−6 | 2.19*10−4 | CXCL14 | NM_004887.3 | −16.8 | 6.96*10−6 | 4.56*10−3 |

| SCARA5 | NM_173833.4 | 6.5 | 1.11*10−6 | 1.93*10−4 | PI16 | NM_153370.2 | −12.7 | 3.53*10−7 | 9.36*10−4 |

| C4orf7 | NM_152997.2 | 6.4 | 1.01*10−4 | 5.34*10−3 | PLA2G2A | NM_000300.2 | −11.5 | 3.91*10−6 | 3.46*10−3 |

| APOLD1 | NM_030817.1 | 6.2 | 8.70*10−12 | 8.98*10−8 | SFRP1 | NM_003012.3 | −11.5 | 5.77*10−6 | 4.22*10−3 |

| SLC14A1 | NM_015865.2 | −6.0 | 2.26*10−6 | 3.30*10−4 | IL6 | NM_000600.1 | −8.3 | 1.01*10−5 | 5.47*10−3 |

| CD19 | NM_001770.4 | 5.8 | 8.32*10−6 | 8.88*10−4 | LOC653879 | XM_936226.1 | −8.3 | 2.13*10−6 | 2.64*10−3 |

| CD79A | NM_021601.3 | 5.8 | 5.19*10−6 | 6.14*10−4 | SPON1 | NM_006108.2 | −7.3 | 3.95*10−5 | 1.04*10−2 |

| C6 | NM_000065.1 | 5.8 | 6.09*10−11 | 1.62*10−7 | C4orf7 | NM_152997.2 | −6.9 | 1.15*10−4 | 1.75*10−2 |

| CCL19 | NM_006274.2 | 5.5 | 6.22*10−8 | 2.34*10−5 | CCL21 | NM_002989.2 | −6.8 | 2.62*10−6 | 2.83*10−3 |

| NLF2 | XM_940314.2 | 5.5 | 3.24*10−9 | 2.76E-*10−6 | CCL19 | NM_006274.2 | −6.3 | 1.65*10−7 | 8.06*10−4 |

| LOC651751 | XM_940969.1 | 5.5 | 2.26*10−6 | 3.30*10−4 | FCRLA | NM_032738.3 | −6.3 | 3.21*10−6 | 3.07*10−3 |

| FBLN1 | NM_001996.2 | 5.5 | 6.22*10−8 | 2.34*10−5 | GREM1 | NM_013372.5 | −6.2 | 1.11*10−8 | 1.71*10−4 |

| NR4A2 | NM_006186.2 | 5.3 | 1.21*10−9 | 1.34*10−6 | C3 | NM_000064.1 | −6.1 | 3.21*10−6 | 3.07*10−3 |

| SPON1 | NM_006108.2 | 5.3 | 1.90*10−6 | 2.89*10−4 | CD79A | NM_001783.3 | −5.9 | 4.76*10−6 | 3.88*10−3 |

| GREM1 | NM_013372.5 | 5.3 | 3.24*10−9 | 2.76*10−6 | SCARA5 | NM_173833.4 | −5.8 | 5.84*10−4 | 3.75*10−2 |

| C7 | NM_000587.2 | 5.3 | 6.09*10−11 | 1.62*10−7 | LOC652694 | XM_942302.1 | −5.8 | 1.21*10−5 | 5.83*10−3 |

| SVEP1 | NM_153366.2 | 5.2 | 3.52*10−7 | 8.23*10−5 | CD79A | NM_021601.3 | −5.5 | 1.21*10−5 | 5.83*10−3 |

| FOSB | NM_006732.1 | 5.2 | 2.37*10−9 | 2.27*10−6 | DARC | NM_002036.2 | −5.4 | 5.84*10−4 | 3.75*10−2 |

| LOC401845 | XM_377426.1 | 5.0 | 1.76*10−5 | 1.55*10−3 | CD19 | NM_001770.4 | −5.4 | 3.36*10−5 | 9.77*10−3 |

| LOC651751 | XM_940969.1 | −5.3 | 1.44*10−5 | 6.28*10−3 | |||||

| ABCA8 | NM_007168.2 | −5.0 | 6.96*10−6 | 4.56*10−3 | |||||

aAbbreviations: FC = fold changes (FC); FDR = False discovery rate.

Altered canonical pathways in advanced atherosclerotic plaques in comparison to LITA

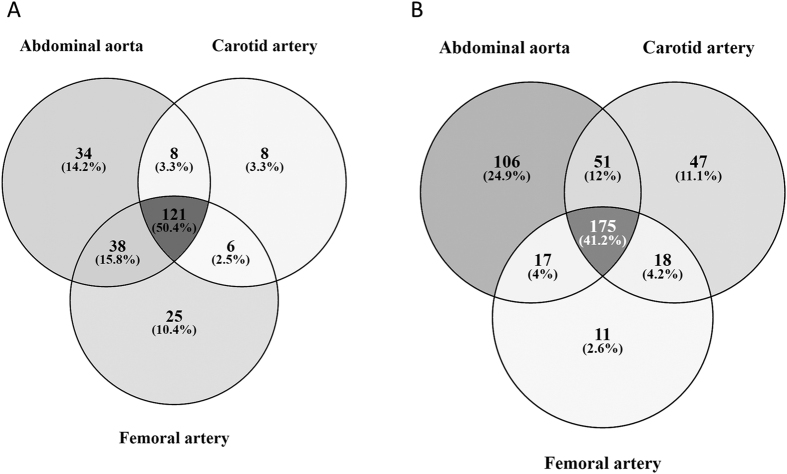

Ingenuity pathway analysis identified 156 altered pathways between atherosclerotic plaques and healthy arteries, with FDR < 0.05, when analyzing genes with FC > ±1.5. In aortic, carotid and femoral plaques 201, 143 and 190 pathways were respectively differentially expressed, of which 121 were shared by all of the arterial beds (Fig. 1A). The top 10 canonical pathways of each arterial bed in comparison to the healthy control to, as well as the top 25 pathways from the analysis of all atherosclerotic arteries versus healthy controls are shown in Tables 3 and 4 and the full list of pathways with significant differential expression is provided in Supplementary File 4. The number of genes up- and downregulated is shown as well as the ratio of differentially expressed genes on the pathway to all the genes on the pathway. Most of the pathways that showed significant (FDR < 0.05) up-regulation in atherosclerotic plaques were related to the inflammatory process in the arterial wall, including inflammatory markers, such as CD4 and CD28, as well as CXCR4. The pathways that are differentially expressed are all closely related to the inflammation and ensuing apoptosis of the cells of the arterial wall. The 121 pathways differentially expressed in all the atherosclerotic arteries are mostly related to the leukocyte activity of arterial wall, involving for example pathways that lead to adhesion and diapedesis of agranulocytes. Abdominal aortic plaques were found to have more unique differentially expressed pathways, including up-regulation of several distinct inflammatory pathways, whilst the 25 pathways differentially expressed only in femoral plaques included several down-regulated catabolic pathways (Table 4).

Figure 1.

A Venn diagram showing the number of (A) Ingenuity Canonical Pathways and (B) GO-terms differentially expressed in different arterial beds and the overlapping of those pathways/GO-terms between atherosclerotic plaques from different arterial beds.

Table 3. Top 25 pathways differentially expressed in advanced atherosclerotic plaques when compared to the healthy left internal thoracic artery (LITA).

| Ingenuity Canonical Pathways | B-H p-value (FDR)a | Ratio: differentially expressed/all pathway genes | Downregulated genes on the pathway | Up-regulated genes on the pathway | Genes not differentially expressed on the pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen Presentation Pathway | 3.89*10−10 | 0.730 | 0/37 (0%) | 27/37 (73%) | 10/37 (27%) |

| Hepatic Fibrosis/Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation | 7.41*10−10 | 0.404 | 21/183 (11%) | 53/183 (29%) | 109/183 (60%) |

| Dendritic Cell Maturation | 7.41*10−10 | 0.407 | 14/177 (8%) | 58/177 (33%) | 105/177 (59%) |

| Crosstalk between Dendritic Cells and Natural Killer Cells | 7.08*10−8 | 0.472 | 6/89 (7%) | 36/89 (40%) | 47/89 (53%) |

| Leukocyte Extravasation Signaling | 7.08*10−8 | 0.369 | 23/198 (12%) | 50/198 (25%) | 125/198 (63%) |

| Role of Macrophages. Fibroblasts and Endothelial Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis | 7.94*10−8 | 0.331 | 29/296 (10%) | 69/296 (23%) | 198/296 (67%) |

| Granulocyte Adhesion and Diapedesis | 1.95*10−7 | 0.373 | 9/177 (5%) | 57/177 (32%) | 111/177 (63%) |

| Type I Diabetes Mellitus Signaling | 7.24*10−7 | 0.418 | 3/110 (3%) | 43/110 (39%) | 64/110 (58%) |

| Axonal Guidance Signaling | 4.17*10−6 | 0.288 | 56/434 (13%) | 69/434 (16%) | 309/434 (71%) |

| TREM1 Signaling | 4.47*10−6 | 0.453 | 1/75 (1%) | 33/75 (44%) | 41/75 (55%) |

| LXR/RXR Activation | 5.62*10−6 | 0.388 | 16/121 (13%) | 31/121 (26%) | 74/121 (61%) |

| Agranulocyte Adhesion and Diapedesis | 1.29*10−5 | 0.339 | 17/189 (9%) | 47/189 (25%) | 125/189 (66%) |

| Communication between Innate and Adaptive Immune Cells | 1.35*10−5 | 0.416 | 2/89 (2%) | 35/89 (39%) | 52/89 (58%) |

| Role of Pattern Recognition Receptors in Recognition of Bacteria and Viruses | 1.35*10−5 | 0.376 | 6/125 (5%) | 41/125 (33%) | 78/125 (62%) |

| CD28 Signaling in T Helper Cells | 1.35*10−5 | 0.381 | 7/118 (6%) | 38/118 (32%) | 73/118 (62%) |

| Role of NFAT in Regulation of the Immune Response | 1.35*10−5 | 0.345 | 14/171 (8%) | 45/171 (26%) | 112/171 (65%) |

| LPS/IL-1 Mediated Inhibition of RXR Function | 2.09*10−5 | 0.321 | 29/221 (13%) | 42/221 (19%) | 150/221 (68%) |

| Graft-versus-Host Disease Signaling | 2.19*10−5 | 0.500 | 1/48 (2%) | 23/48 (48%) | 24/48 (50%) |

| CTLA4 Signaling in Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes | 7.08*10−5 | 0.398 | 6/88 (7%) | 29/88 (33%) | 53/88 (60%) |

| NF-ΰB Signaling | 7.08*10−5 | 0.331 | 16/172 (9%) | 41/172 (24%) | 115/172 (67%) |

| Production of Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species in Macrophages | 7.08*10−5 | 0.328 | 16/180 (9%) | 43/180 (24%) | 121/180 (67%) |

| ILK Signaling | 8.13*10−5 | 0.324 | 35/185 (19%) | 25/185 (14%) | 125/185 (68%) |

| FcÎ3 Receptor-mediated Phagocytosis in Macrophages and Monocytes | 8.91*10−5 | 0.387 | 7/93 (8%) | 29/93 (31%) | 57/93 (61%) |

| Integrin Signaling | 1.02*10−4 | 0.314 | 30/207 (14%) | 35/207 (17%) | 142/207 (69%) |

| Complement System | 1.38*10−4 | 0.514 | 4/37 (11%) | 15/37 (41%) | 18/37 (49%) |

ap-value calculated with Benjamini-Hochberg method.

Table 4. Top 10 differentially expressed canonical pathways from atherosclerotic plaques from different arterial beds (abdominal aorta, carotid, femoral) in comparison to left internal thoracic artery controls.

| Ingenuity Canonical Pathways | B-H p-value (FDR) | Ratio: differentially expressed/all pathway genes | Downregulated genes on the pathway | Up-regulated genes on the pathway | Genes not differentially expressed on the pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic vs LITA | |||||

| Hepatic Fibrosis/Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation | 5.01*10−13 | 0.470 | 23/183 (13%) | 63/183 (34%) | 97/183 (53%) |

| Dendritic Cell Maturation | 1.00*10−12 | 0.469 | 15/177 (8%) | 68/177 (38%) | 94/177 (53%) |

| Role of Macrophages. Fibroblasts and Endothelial Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis | 3.89*10−10 | 0.382 | 32/296 (11%) | 81/296 (27%) | 183/296 (62%) |

| Granulocyte Adhesion and Diapedesis | 1.74*10−9 | 0.429 | 8/177 (5%) | 68/177 (38%) | 101/177 (57%) |

| Crosstalk between Dendritic Cells and Natural Killer Cells | 2.00*10−9 | 0.528 | 6/89 (7%) | 41/89 (46%) | 42/89 (47%) |

| Leukocyte Extravasation Signaling | 1.32*10−8 | 0.404 | 21/198 (11%) | 59/198 (30%) | 118/198 (60%) |

| Axonal Guidance Signaling | 1.66*10−8 | 0.334 | 64/434 (15%) | 81/434 (19%) | 289/434 (67%) |

| Type I Diabetes Mellitus Signaling | 2.29*10−8 | 0.473 | 3/110 (3%) | 49/110 (45%) | 58/110 (53%) |

| Antigen Presentation Pathway | 5.62*10−8 | 0.676 | 0/37 (0%) | 25/37 (68%) | 12/37 (32%) |

| TREM1 Signaling | 9.33*10−8 | 0.520 | 1/75 (1%) | 38/75 (51%) | 36/75 (48%) |

| Carotid vs LITA | |||||

| Hepatic Fibrosis/Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation | 3.31*10−10 | 0.432 | 25/183 (14%) | 54/183 (30%) | 104/183 (57%) |

| Dendritic Cell Maturation | 5.75*10−9 | 0.418 | 16/177 (9%) | 58/177 (33%) | 103/177 (58%) |

| Axonal Guidance Signaling | 1.86*10−7 | 0.320 | 61/434 (14%) | 78/434 (18%) | 295/434 (68%) |

| Granulocyte Adhesion and Diapedesis | 1.86*10−7 | 0.395 | 11/177 (6%) | 59/177 (33%) | 107/177 (60%) |

| Crosstalk between Dendritic Cells and Natural Killer Cells | 1.86*10−7 | 0.483 | 6/89 (7%) | 37/89 (42%) | 46/89 (52%) |

| Antigen Presentation Pathway | 3.16*10−7 | 0.649 | 0/37 (0%) | 24/37 (65%) | 13/37 (35%) |

| Leukocyte Extravasation Signaling | 6.76*10−7 | 0.374 | 23/198 (12%) | 51/198 (26%) | 124/198 (63%) |

| TREM1 Signaling | 7.59*10−7 | 0.493 | 1/75 (1%) | 36/75 (48%) | 38/75 (51%) |

| Agranulocyte Adhesion and Diapedesis | 4.90*10−6 | 0.365 | 19/189 (10%) | 50/189 (26%) | 120/189 (63%) |

| Role of Macrophages. Fibroblasts and Endothelial Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis | 6.03*10−6 | 0.328 | 29/296 (10%) | 68/296 (23%) | 199/296 (67%) |

| Femoral vs LITA | |||||

| Leukocyte Extravasation Signaling | 3.98*10−11 | 0.404 | 26/198 (13%) | 54/198 (27%) | 118/198 (60%) |

| Hepatic Fibrosis/Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation | 1.48*10−10 | 0.404 | 20/183 (11%) | 54/183 (30%) | 109/183 (60%) |

| Dendritic Cell Maturation | 1.48*10−10 | 0.407 | 15/177 (8%) | 57/177 (32%) | 105/177 (59%) |

| Antigen Presentation Pathway | 4.57*10−8 | 0.649 | 0/37 (0%) | 24/37 (65%) | 13/37 (35%) |

| Role of Macrophages. Fibroblasts and Endothelial Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis | 8.13*10−8 | 0.324 | 28/296 (9%) | 68/296 (23%) | 200/296 (68%) |

| Granulocyte Adhesion and Diapedesis | 1.58*10−7 | 0.367 | 7/177 (4%) | 58/177 (33%) | 112/177 (63%) |

| TREM1 Signaling | 1.62*10−7 | 0.48 | 1/75 (1%) | 35/75 (47%) | 39/75 (52%) |

| Crosstalk between Dendritic Cells and Natural Killer Cells | 2.88*10−6 | 0.427 | 6/89 (7%) | 32/89 (36%) | 51/89 (57%) |

| Integrin Signaling | 3.24*10−6 | 0.333 | 33/207 (16%) | 36/207 (17%) | 138/207 (67%) |

| Production of Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species in Macrophages | 3.55*10−6 | 0.344 | 19/180 (11%) | 43/180 (24%) | 118/180 (66%) |

GO-term analyses showed that 288 Go terms were up-regulated in atherosclerotic plaques in comparison to controls (Supplementary File 5). Similarly to IPA pathway analysis gene sets up-regulated in individual arterial beds greatly overlapped (Fig. 1B) and were mostly related to inflammatory processes (Supplementary File 4). As with the IPA pathways, aortic plaques had the greatest number of unique differentially expressed gene sets. Only GO term “ncRNA metabolic process” was down-regulated in carotid plaques in comparison to controls.

Discussion

Our results underline the importance of osteopontin in the development of atherosclerosis and suggest that the different expression of cell death-inducing DFFA-like effector C and A may also be involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. These results offer more specified and wider information on the biochemical pathways differentially expressed (against most recently updated data bases) in atherosclerotic plaques, artery type specific expression information and further extend and specify the previously published results. We demonstrate the extensively individual genes that are differentially expressed and biological pathways in atherosclerotic plaques using the unique sample collection of the TVS. Perisic et al.32 conducted a similar study, which yielded similar results, where atherosclerotic plaques were compared to blood samples from, we consider using a healthy artery to be a more valid method as the tissues are more alike. The differentially expressed genes and pathways reported here are mostly involved in the inflammatory events previously assumed to occur in the atherosclerotic arterial wall, i.e. the recruitment and translocation of leucocytes through the intimal layer and infiltration of the vessel wall, differentiation of macrophages to foam cells, and the remodeling of extracellular matrix, which affects the stability of the plaque.

Osteopontin was the most up-regulated gene in the atherosclerotic plaques in comparison to healthy control arteries. Ikeda et al. have previously shown atherosclerotic severity dependent expression of osteopontin in human aortic plaques33 and osteopontin has also been connected to coronary artery disease in a large GWAS study34. Osteopontin is a key component in inflammatory processes, involved in cell migration and as a chemoattractant for monocytes35 and in adhesion in vascular and T-cells35. Our results showing the up-regulation of osteopontin are supported also by previous evidence that it is expressed by foam cells derived from smooth muscle cells33 and that it has been indicated in the calcification process of the atherosclerotic plaque. Osteopontin has the ability to bind calcium25,36 which is presumed to be a response to prevent further mineralization of the plaque37. Osteopontin also participates in the recruitment and further differentiation of macrophages36, through this role, the expression levels of osteopontin also correlate with the plaques’ stability as the amount and subtype of macrophages correlate with plaque stability. Due to the wide range of effects and excessive expression in the plaque tissue, osteopontin is clearly one of the key players in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Interferon beta has been shown to modulate the expression of osteopontin by Chen et al.38 in multiple sclerosis and our results suggest it might be an interesting pharmacological approach in atherosclerosis as well.

Also cathepsins, a group of proteinases including some collagenases and bone reabsorption associated enzymes, some of which are known to participate in vascular diseases39 were significantly up-regulated. Now our results give context and show the role of cathepsins (CTS) in relation to other differentially expressed genes as part of the complex process of atherosclerosis pathogenesis.

Several multiple matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) showed very substantial up-regulation in atherosclerotic plaques. Our results further affirm the role of two MMPs (MMP12 and −9) previously associated with stroke in GWAS analysis by the METASTROKE collaboration40, and carotid artery atherosclerosis32. MMPs are peptidases that have been shown to participate in vascular remodeling14 and plaque formation14 as well as in plaque rupture39 in atherosclerotic arteries. They also have modulatory functions in cell signaling41. In our pathway analysis MMPs were found in canonical pathways related to adhesion and diapedesis of leukocytes, facilitating the transmigration of leukocytes through endothelial layer. Of the MMP family MMP7, MMP9, MMP11 and MMP12 had the highest up-regulation levels with different proportional levels in different arterial beds. The abundance of MMP9 in femoral plaques and MMP12 in carotid plaques supports the idea of MMPs expression in plaque formation being site-, and possibly sex-, specific42,43.

Differentially expressed lipid metabolism related genes included CIDEC, CIDEA and apolipoproteins E, D and C1. The up-regulation of ApoE and ApoC1 in our advanced atherosclerotic artery samples seem to support the correlations that have been found with lipid deposits and cholesterol accumulation44 and plaque size45. Interestingly, in our study we also showed that ApoD was down-regulated in the plaque tissue. CIDEC and CIDEA have previously been associated with the intake of lipids and formation of lipid droplets in macrophage derived foam cells46. Therefore, their down-regulation may indicate decreased foam cell formation in advanced atherosclerotic plaques or possibly other currently unknown roles in the atherosclerotic plaque47.

Several chemokines, as well as their receptors, were up-regulated, the most important ones being CCL5 and CCL2. These have been shown to be involved in chemokinesis, dendritic cell signaling48, monocyte recruitment49 and enhancement of vascular permeability, all of which fit the pathology of atherosclerosis and have been associated with several pathological conditions50, including, but not limited to, atherosclerosis50.

From our results we can speculate that the genes differently expressed in plaques from different arterial beds might help to explain as to why certain plaques tend to be more stable and calcify or become fibrotic. The delay to surgery is shorter in carotid surgery, as opposed to femoral artery or abdominal aorta, because they often contain an unstable plaque and are highly symptomatic. This is likely to explain a part of the different expression patterns in the carotid plaques. As the carotid plaques are more frequently unstable the role of MMP12 and −7 might warrant further research, as our results show that of all the arterial beds these MMPs have the greatest expression in carotid artery samples. Also, our results suggest the role of homeobox-genes as stabilizing elements because two homeobox genes, HOXC6 and HOXA5 (Table 2), were the significantly down-regulated genes in carotid artery as opposed to the femoral artery and abdominal aorta.

Our pathway analysis results are well in line with previous analysis done with smaller sample sets or with those deduced from GWAS results. When comparing IPA pathways enriched with genes associated with CAD34 or large artery stroke51 in GWAS, our data indicated 44 pathways out of the 96 pathways connected with CAD were differentially expressed and 11 pathways out of the 16 connected with large artery stroke17. Moreover 12 out of the 16 pathways previously connected to large artery stroke were differentially expressed in carotid plaques in comparison to controls17. The GO terms with significant different expression are also very similar to those found by Nai et al.16. Although their analysis contained only carotid plaques and they used different control material - the healthy arteries obtained near the plaques -the pathways identified in their study well match our results. In addition, 9 of the 10 most up-regulated GO terms in their study are up-regulated also in our data, and although “cytokine production” is not up-regulated in our results, “regulation of cytokine production” is ref. 16. Similar GO terms have also been shown to be enriched in the study conducted by Perisic et al.32.

Our pathway analysis highlights the importance of inflammation related pathways also in advanced atherosclerotic plaques. The pathways activated show that the movement and attachment of leukocytes is a crucial part of the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Also the remodeling of extracellular matrix and differentiation of cells producing extracellular components were activated, such as the pathway of hepatic stellate cell activation. The GO term search further affirmed the results of the inflammatory nature of atherosclerosis, as many of the GO terms were inflammation related. Our results also show that similar pathways are differentially expressed in peripheral atherosclerotic plaques from different locations, but abdominal aortic plaques have more inflammatory pathways up-regulated and down-regulation of several catabolic pathways can only be seen in femoral plaques.

Limitations of the study

The different hemodynamics associated with plaque localization on the arterial wall might have contributed to the results, along with the fact that controls had coronary artery disease, which implies similar systemic factors. In our study we used the LITA samples as control, as LITA is usually quite impervious to atherosclerosis52, and is therefore widely used as a control material in similar studies. Control samples from corresponding arterial beds free of atherosclerosis and from healthy subjects without systemic risk factors could have provided more precise analysis. However, due to ethical reasons we were not able to obtain such samples. In endarterectomy, intima mainly containing the plaque and inner media are removed. In non-atherosclerotic LITA control arteries, it is not feasible to remove the adventitia and outer media. Due to this setting, the LITA samples include the thin adventitia consisting mainly of loose connective tissue, whilst plaque samples lack the adventitial layer. This should not reduce the validity or hamper interpretation of our results. The suitability of LITAs as controls16 is further supported by our results being well in line with the Gene ontology results performed with carotid plaques and adjacent healthy tissues as controls by Perisic et al.32. In addition, we have previously shown that the tissue morphology is similar in LITA samples, healthy carotid artery, and abdominal aorta and verified the similar expression patterns of focal adhesion molecules in these healthy arterial beds53.

Both cases and controls had similar prevalence of statin users, with 87.5% of cases and 73.5% of controls (Supplementary File 1) and we therefore consider the groups comparable. High rate of statin usage may have some effect on gene expression but does not explain the differences between cases and controls. However, it is noteworthy that we cannot separate the changes in gene expression caused by the pathological state from those caused by statins or other medication. As majority of the samples were advanced atherosclerotic plaques, more research is needed to determine the dominant genes and pathways active in more early phases of the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. We do not use qRT-PCR to further affirm our results as it has been shown by Raitoharju et al.23 that when FC > 3 the specificity is 100% and when FC > 1.5 it is 73.7%.

In conclusion, the development of atherosclerotic plaque extensively disturbs the function of the human arterial wall and leads to different expression of a multitude of genes and pathways. Our gene expression analysis from human peripheral atherosclerotic plaques confirm the previous associations of many differentially expressed gene families, such as matrix metalloproteinases, apolipoproteins and cholesterol related receptors. Also, the role of osteopontin as one of the central genes in atherosclerosis was underlined in our results, as it was the single gene with the greatest fold change in our samples, possibly having a role in the calcification process and progression of atherosclerotic plaques. We also report for the first time the down-regulation of ApoD in human atherosclerotic plaques, and although its association with atherosclerosis is indisputable its role is still not completely understood. The inflammatory nature of the disease was further supported here, as many inflammatory pathways were differentially expressed in the advanced peripheral atherosclerotic plaques. As seen in Fig. 1, atherosclerosis has significant differences in gene expression depending on the site of the arterial plaque, and only 50.4% of IPA pathways and 41.2% of GO terms are in common between all atherosclerosis affected arteries. These results will serve as a good map for further research on the genes and pathways behind human atherosclerosis.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Sulkava, M. et al. Differentially expressed genes and canonical pathway expression in human atherosclerotic plaques – Tampere Vascular Study. Sci. Rep. 7, 41483; doi: 10.1038/srep41483 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Union 7th Framework Programme funding for the AtheroRemo project [201668], the Competitive Research Funding of Tampere University Hospital [grant X51001 for T.L and 9S054 for E.R], the Academy of Finland: grants 286284 (T.L.), 285902 (E.R.), Finnish Foundation of Cardiovascular Research (T.L.); Finnish Cultural Foundation; Tampere Tuberculosis Foundation (T.L.); Emil Aaltonen Foundation (T.L. and N.O.); and Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation (T.L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions M.S. wrote the manuscript and performed statistical analysis. E.R. acquired data, reviewed/edited the manuscript and acquired funding. M.L. participated in cohort collection and acquired data. I.S. performed statistical analysis and reviewed the manuscript. L.-P.L. performed statistical analysis. A.M., J.-P.S. and T.I acquired data and reviewed the manuscript. O.J., R.Z. and N.K. acquired data. N.M. participated in cohort collection and reviewed/edited the manuscript. R.L. acquired funding. M.K. acquired funding and reviewed the manuscript. N.O. acquired data, participated and organized cohort collection and supervision, and reviewed/edited the manuscript. T.L. handled funding and supervision, participated in cohort collection and reviewed/edited the manuscript.

References

- Gargiulo P. et al. Ischemic heart disease in systemic inflammatory diseases. An appraisal. Int. J. Cardiol. 170, 286–290 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levula M. et al. Genes involved in systemic and arterial bed dependent atherosclerosis–Tampere Vascular study. PLoS One 7, e33787 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herisson F. et al. Carotid and femoral atherosclerotic plaques show different morphology. Atherosclerosis 216, 348–354 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde L. et al. Novel associations for coronary artery disease derived from genome wide association studies are not associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness, suggesting they do not act via early atherosclerosis or vessel remodeling. Atherosclerosis 219, 684–689 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K. J. & Tabas I. The response-to-retention hypothesis of early atherogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15, 551–561 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stary H. C. Changes in components and structure of atherosclerotic lesions developing from childhood to middle age in coronary arteries. Basic Res. Cardiol. 89 Suppl 1, 17–32 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R. Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 340, 115–126 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentzon J. F., Otsuka F., Virmani R. & Falk E. Mechanisms of plaque formation and rupture. Circ. Res. 114, 1852–1866 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starke R. M. et al. Vascular smooth muscle cells in cerebral aneurysm pathogenesis. Transl. Stroke Res. 5, 338–346 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimbrone M. A. Jr. & Garcia-Cardena G. Vascular endothelium, hemodynamics, and the pathobiology of atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 22, 9–15 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonarduzzi G., Gamba P., Gargiulo S., Biasi F. & Poli G. Inflammation-related gene expression by lipid oxidation-derived products in the progression of atherosclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 52, 19–34 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttolomondo A. et al. Atherosclerosis as an inflammatory disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 18, 4266–4288 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomisto T. T. et al. Gene expression in macrophage-rich inflammatory cell infiltrates in human atherosclerotic lesions as studied by laser microdissection and DNA array: overexpression of HMG-CoA reductase, colony stimulating factor receptors, CD11A/CD18 integrins, and interleukin receptors. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 2235–2240 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galis Z. S. & Khatri J. J. Matrix metalloproteinases in vascular remodeling and atherogenesis: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Circ. Res. 90, 251–262 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Li Y. S. & Chien S. Shear stress-initiated signaling and its regulation of endothelial function. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 34, 2191–2198 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nai W. et al. Identification of novel genes and pathways in carotid atheroma using integrated bioinformatic methods. Sci. Rep. 6, 18764 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasterkamp G. et al. Human Validation of Genes Associated With a Murine Atherosclerotic Phenotype. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey S. A. et al. Epigenome-guided analysis of the transcriptome of plaque macrophages during atherosclerosis regression reveals activation of the Wnt signaling pathway. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004828 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksala N. et al. Kindlin 3 (FERMT3) is associated with unstable atherosclerotic plaques, anti-inflammatory type II macrophages and upregulation of beta-2 integrins in all major arterial beds. Atherosclerosis 242, 145–154 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksala N. et al. Association of neuroimmune guidance cue netrin-1 and its chemorepulsive receptor UNC5B with atherosclerotic plaque expression signatures and stability in human(s): Tampere Vascular Study (TVS). Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 6, 579–587 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y. M. et al. Upstream Transcription Factor 1 (USF1) allelic variants regulate lipoprotein metabolism in women and USF1 expression in atherosclerotic plaque. Sci. Rep. 4, 4650 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turpeinen H. et al. Proprotein convertases in human atherosclerotic plaques: the overexpression of FURIN and its substrate cytokines BAFF and APRIL. Atherosclerosis 219, 799–806 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raitoharju E. et al. A comparison of the accuracy of Illumina HumanHT-12 v3 Expression BeadChip and TaqMan qRT-PCR gene expression results in patient samples from the Tampere Vascular Study. Atherosclerosis 226, 149–152 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksala N. et al. ADAM-9, ADAM-15, and ADAM-17 are upregulated in macrophages in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques in aorta and carotid and femoral arteries–Tampere vascular study. Ann. Med. 41, 279–290 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksala N. et al. Carbonic anhydrases II and XII are up-regulated in osteoclast-like cells in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques-Tampere Vascular Study. Ann. Med. 42, 360–370 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turpeinen H. et al. A genome-wide expression quantitative trait loci analysis of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin enzymes identifies a novel regulatory gene variant for FURIN expression and blood pressure. Hum. Genet. 134, 627–636 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raitoharju E. et al. miR-21, miR-210, miR-34a, and miR-146a/b are up-regulated in human atherosclerotic plaques in the Tampere Vascular Study. Atherosclerosis 219, 211–217 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stary H. C. et al. A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation 92, 1355–1374 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y. & Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 57, 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Eden E., Navon R., Steinfeld I., Lipson D. & Yakhini Z. GOrilla: a tool for discovery and visualization of enriched GO terms in ranked gene lists. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 48–2105–10–48 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html.

- Perisic L. et al. Gene expression signatures, pathways and networks in carotid atherosclerosis. J. Intern. Med. 279, 293–308 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda T., Shirasawa T., Esaki Y., Yoshiki S. & Hirokawa K. Osteopontin mRNA is expressed by smooth muscle-derived foam cells in human atherosclerotic lesions of the aorta. J. Clin. Invest. 92, 2814–2820 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schunkert H. et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat. Genet. 43, 333–338 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund S. A., Giachelli C. M. & Scatena M. The role of osteopontin in inflammatory processes. J. Cell. Commun. Signal. 3, 311–322 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Regan A. & Berman J. S. Osteopontin: a key cytokine in cell-mediated and granulomatous inflammation. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 81, 373–390 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolak T. Osteopontin - a multi-modal marker and mediator in atherosclerotic vascular disease. Atherosclerosis 236, 327–337 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. et al. Regulatory effects of IFN-beta on production of osteopontin and IL-17 by CD4+ T Cells in MS. Eur. J. Immunol. 39, 2525–2536 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby A. C. Proteinases and plaque rupture: unblocking the road to translation. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 25, 358–366 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traylor M. et al. A novel MMP12 locus is associated with large artery atherosclerotic stroke using a genome-wide age-at-onset informed approach. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004469 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanjul-Fernandez M., Folgueras A. R., Cabrera S. & Lopez-Otin C. Matrix metalloproteinases: evolution, gene regulation and functional analysis in mouse models. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803, 3–19 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra R. et al. The role of matrix metalloproteinases and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in central and peripheral arterial aneurysms. Surgery 157, 155–162 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Chai H., Ding R. & Lam H. Y. Distribution of inflammatory mediators in carotid and femoral plaques. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 211, 92–98 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins I. J. et al. Apolipoprotein E, cholesterol metabolism, diabetes, and the convergence of risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease and cardiovascular disease. Mol. Psychiatry 11, 721–736 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noto A. T., Mathiesen E. B., Brox J., Bjorkegren J. & Hansen J. B. The ApoC-I content of VLDL particles is associated with plaque size in persons with carotid atherosclerosis. Lipids 43, 673–679 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Identification by microarray technology of key genes involved in the progression of carotid atherosclerotic plaque. Genes Genet. Syst. 89, 253–258 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Zhou L. & Li P. CIDE proteins and lipid metabolism. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 1094–1098 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessner A. & Weyand C. M. Dendritic cells in atherosclerotic disease. Clin. Immunol. 134, 25–32 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuschner F. et al. Therapeutic siRNA silencing in inflammatory monocytes in mice. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 1005–1010 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor T., Borsig L. & Heikenwalder M. CCL2-CCR2 Signaling in Disease Pathogenesis. Endocr Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 15, 105–118 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traylor M. et al. Genetic risk factors for ischaemic stroke and its subtypes (the METASTROKE collaboration): a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol. 11, 951–962 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajja L. R. & Mannam G. Internal thoracic artery: anatomical and biological characteristics revisited. Asian Cardiovasc. Thorac. Ann. 23, 88–99 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Essen M. et al. Talin and vinculin are downregulated in atherosclerotic plaque; Tampere Vascular Study. Atherosclerosis 255, 43–53 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.