Abstract

Background:

In many patients, emotional stress may exacerbate acne. Psychological problems such as social phobias, low self-esteem, or depression may also occur as a result of acne. The presence of acne may have some negative effect on the quality of life, self-esteem, and mood of the affected patients. While some studies have been undertaken about anxiety, depression, and personality patterns in patients with acne, only a few studies have been done to identify specific personality disorders in patients with acne. Furthermore, there is a dearth of data regarding the effect of personality disorder on the psychological states of the patients which prompted us to undertake the present study.

Methodology:

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study, undertaken in a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital in Eastern India. Consecutive patients suffering from severe (Grade 3 and 4) acne, attending the Dermatology Outpatient Department, aged above 18 years were included to the study.

Results:

A total of 65 patients were evaluated with a mean age of 26 years. Personality disorder was present in 29.2% of patients. The diagnosed personality disorders were obsessive compulsive personality disorder (n = 9, 13.8%), anxious (avoidant) personality disorder (n = 6, 9.2%), and borderline personality disorder (n = 2, 3%), mixed personality disorder (n = 2, 3%). All patients with personality disorder had some psychiatric comorbidity. Patients having personality disorder had higher number of anxiety and depressive disorders which were also statistically significant.

Conclusion:

The present study highlights that personality disorders and other psychiatric comorbidities are common in the setting of severe acne.

Key words: Anxiety, depression, personality disorders, severe acne

INTRODUCTION

A relationship between psychological factors and skin diseases has long been hypothesized. Psychodermatology addresses the interaction between the mind and the skin.[1] As the brain and the skin have the same developmental origin, i.e., the embryonic ectoderm and are under the influence of the same hormones and neurotransmitters, there might be a close relationship between them. While psychiatrists focus on the “internal indiscernible disease,” dermatologists focus on “external discernible disease.”[2]

Psychological factors might have an important role in the causation of acne in several ways. In many patients, emotional stress may aggravate acne. In a number of patients, psychological problems such as, social phobias, low self-esteem, or depression may arise as a consequence of acne. Moreover, primary psychiatric illnesses such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and psychosis may be deeply rooted to a complaint that is focused on acne.[3] The presence of acne might have some negative effect on the quality of life, self-esteem, and mood in adolescents. Acne is associated with an increased incidence of anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. The presence of these and other comorbid psychological disorders should be addressed in the treatment of patients with acne, when appropriate. A strong physician-patient relationship and thorough history taking are of paramount importance to identify the patients at risk for the adverse psychological effects of acne.[4] Several studies have showed that psychiatric comorbidity of acne excoriee includes body image disorder, depression, anxiety, OCD, delusional disorders, personality disorders, and social phobias.[5,6,7,8] It is noteworthy that the effect of acne on psychosocial and emotional problems is analogous to the effects of arthritis, back pain, diabetes, epilepsy, and disabling asthma.[9] Acne has a definite association with depression, anxiety, and feelings of social isolation; it affects personality, emotions, self-image, self-esteem, and the ability to form interpersonal relationships.[10,11]

A prevalence rate of suicidal ideation to the tune of 5.6% was observed among patients who had noncystic facial acne.[12]

Although several studies have been undertaken about anxiety, depression, and personality patterns in patients with acne, only a few studies have tried to identify specific personality disorders in patients of acne vulgaris. Moreover, there is a paucity of data regarding the effect of personality disorder on the psychological states of the patients. These prompted the authors to undertake the present study to find out the presence and effect of personality disorder in patients with severe acne.

METHODOLOGY

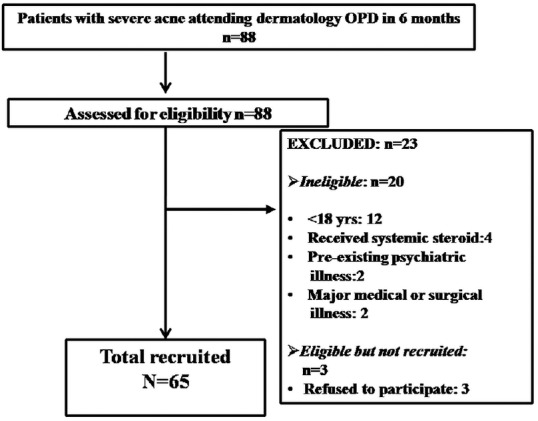

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study, undertaken in the Dermatology and Psychiatry Outpatient Department (OPD) of a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital in Kolkata, in Eastern India. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. The total duration of the study was 6 months (from June 2014 to November 2014). Consecutive patients suffering from severe (Grade 3 and 4) acne,[13] attending the Dermatology OPD, aged above 18 years and giving consent were included to the study [Figure 1]. Patients receiving oral steroid, and sulfonamides and those who were suffering from other major medical or surgical condition, mental retardation, or gross psychotic features were excluded from the study. A predesigned, pretested, semi-structured schedule was used to collect sociodemographic data (age, gender, religion, area of residence, education, family type, marital status, occupation, and per capita income/month).

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the process of recruitment of patients

A detailed psychiatric history was taken, and the mental status examination was done in each and every patient. Personality disorder was diagnosed by the ICD-10 International Personality Disorder Examination[14] by two psychiatrists and a clinical psychologist.

Anxiety and depression were diagnosed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview version 5.[15] Severity of anxiety was assessed by the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A).[16]

The severity of depression was assessed by the Hamilton's Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D).[17] Statistical analysis was done by Chi-square test using GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad software Inc., San Diego; 2007), and Microsoft Excel software.

Operational definition

Grade 3 acne was defined as predominantly pustules, nodules, and abscesses. Grade 4 was defined as mainly, pseudocysts, abscesses, and widespread scarring.[13]

RESULTS

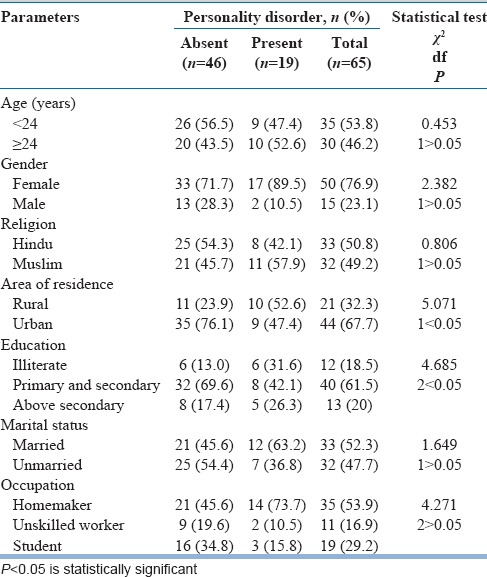

A total of 65 patients were evaluated [Tables 1–3] with a mean age of 26 years with standard deviation (SD) of 7.5. Out of them, 76.9% (n = 50) were female, 50.8% (n = 33) were Hindu, 67.7% (n = 44) belonged to urban residence, 61.5% (n = 40) had studied up to primary and secondary class, 52.3% (n = 34) was married, 61.5% (n = 40) belonged to nuclear family and 53.9% (n = 35) were homemakers. Personality disorder was present in 29.2% (n = 19) patients. The psychiatric diagnosis was major depressive disorder (n = 18, 27.7%), generalized anxiety disorder (n = 10,15.4%), OCD (n = 9, 13.8%), social anxiety disorder (n = 6, 9.23%), dysthymia (n = 5, 7.7%), panic disorder with agoraphobia (n = 2, 3.07%), and panic disorder without agoraphobia (n = 2, 3%). The mean and SD of HAM-D were 13.1 and 2.9, respectively. On the other hand, the mean and SD of HAM-A were 24 and 7.3, respectively.

Table 1.

Association between sociodemographic factors and personality disorder

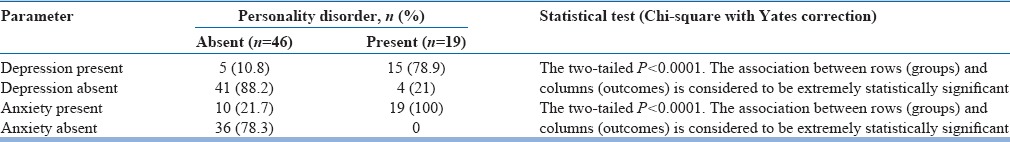

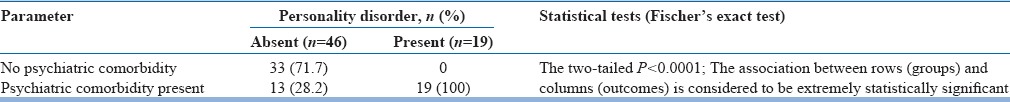

Table 3.

Association between personality disorder and the presence of anxiety and depressive disorders (n=65)

Table 2.

Association between personality disorder and psychiatric comorbidity (n=65)

The diagnosed personality disorders were obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (n = 9, 13.8%), anxious (avoidant) personality disorder (n = 6, 9.2%), borderline personality disorder (n = 2, 3%), and mixed personality disorder (n = 2, 3%). Aged 24 years or more, female gender, Muslims, rural population, persons from lower educational background, married, and homemakers were mostly suffered from personality disorders.

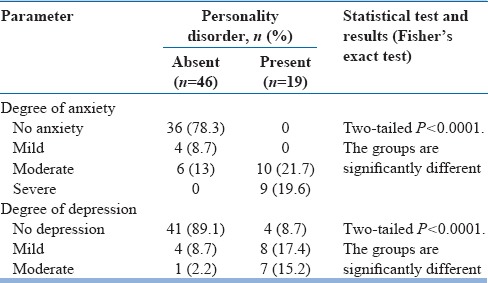

All patients (n = 19) with personality disorder had some psychiatric comorbidity. Patients having personality disorder had higher number of anxiety and depressive disorders which were also statistically significant. They suffered from more severe anxiety and depression as measured by HAM-A and HAM-D, respectively [Table 4].

Table 4.

Association between personality disorder and severity of anxiety and depression (n=65)

DISCUSSION

The psychological and social impacts of acne are a matter of serious concern nowadays. This occurs in view of the fact that acne affects adolescents at a crucial stage of life when they are developing their personalities. All through this period, peer acceptance is extremely important to the teenager and regrettably; it has been found that there are strong associations between physical appearance and attractiveness and peer status. In the present study, a significant portion of patients with severe acne vulgaris had personality disorders.

About half of the study population had some anxiety and depressive disorders. The risk of having such psychiatric morbidity is higher in those having personality disorders. Personality disorders are associated with increased severity of anxiety and depression.

Various studies have dealt with anxiety and depression among acne patients previously. A qualitative review of the selected articles by Dunn et al. revealed that the presence of acne has a significant impact on self-esteem and quality of life. Depression and other psychological disorders are more prevalent in acne patients, and treatment of acne might improve symptoms of these disorders.[4] The present study also supported this observation as 30.8% patients of this study population had depression, and 44.6% patients had anxiety.

Niemeier et al. evaluated a specific questionnaire for patients with chronic skin disorders (CSDs). The CSD revealed significant differences compared to a control group. In addition, the patients' attitudes toward triggering factors and disease-related limitations in everyday life were evaluated. The results of the study showed that patients with acne suffered from emotional distress and psychosocial problems caused by their disease though impairment is not correlated with the objective severity of acne.[18]

In another study, Gupta and Gupta examined the prevalence of depression, death wish, and acute suicidal ideation among 480 patients with dermatological disorders that may be cosmetically disfiguring. Severely affected psoriasis inpatients had most severe depression, followed by the patients with mild to moderate acne. They reported 5.6%–7.2% prevalence of active suicidal ideation among acne patients, which was higher than the 2.4%–3.3% prevalence reported among general medical patients. Although nearly one-third of the subjects of the present study had some depressive disorders, none of them had suicidal ideation or severe depression.[12]

Another study by Picardi et al. found a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders in women and in widows/widowers, controlling for age. High prevalence rates (>30%) were noted among patients with acne, pruritus, urticaria, alopecia, and herpes virus infections. However, they did not find high level of anxiety disorders.[19] We had found a much higher rate of psychiatric comorbidities in the present study.

There are relatively a few studies that deal with personality disorders in dermatology patients. A study by Malick et al. found that patients seeking cosmetic surgery commonly present with psychiatric disorders including body dysmorphic disorder, narcissistic personality disorder, and histrionic personality disorder.[20] Although this study did not exclusively deal with acne patients, it suggests that dermatology patients have high incidence of personality disorders, which was supported by our findings. Unlike the index study, they found that cluster B personality disorders are more common.

Gupta et al. reported major depressive disorder is the most frequently encountered psychiatric disorder in dermatology and are often associated with suicide risk. In this study, other psychiatric syndromes comorbid with dermatologic disorders include OCD, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder associated with dissociation and conversion symptoms, body image pathologies, delusional disorder, and a wide range of personality disorders.[21]

We could not find some of the psychiatric disorders mentioned here. In another study by Gupta et al., ratings associated with poor self-concept, correlated more strongly with self-excoriative behavior than the dermatologic indices of acne severity.[22] In the present study, we found high incidence of similar personality disorders though we did not assess self-excoriating behavior.

In another study by Rasoulian et al., among dermatology outpatients and controls, 70% of the patients and 20% of the control group reported moderate to severe anxiety and depression. Out of them, 15.2% patients and 5% of the controls suffered from personality disorders. Like the index study, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder was the most commonly diagnosed personality disorder.[23]

When the skin is blemished by a disease, it has an immense impact on the mind of the affected person. The intensity of the outcome might depend on several variables including the natural history of the disease, the characteristics of the individual patients, and their condition of life, as well as the attitudes and assumptions of the culture at large about the meaning of skin disease.[24] The presence of comorbid psychological disorders, especially personality disorders should be given due importance in the treatment of acne patients. Future trials are also needed to assess the impact of treatment on psychological outcome.

Patients with personality disorders can be considered as a distinctive group who are at increased risk of anxiety and depression, leading to poor quality of life, compliance, and treatment outcomes.

The existing literature shows that the lifetime prevalence of all depressive disorders taken together is over 20% in general population.[25] On the other hand, near about one-third (30.8%) of the study population of the index study had depression. In a meta-analysis of 13 psychiatric epidemiological studies, Reddy and Chandrashekar found that the prevalence rate of 20.7% (18.7–22.7) for all neurotic disorders.[26] In comparison, in the present study, the occurrence of anxiety disorders was quite high (44.6%). Maanasa et al. reported that the prevalence of personality disorder was 21.55% among psychiatric inpatients.[27] In the present study, 29.2% patients had some kind of personality disorder.

Limitations

There were a few limitations of the present study. Lack of a control group remained one limitation of this study. In addition, it was a hospital-based study with a relatively small study population. Only severe acne vulgaris patients were included in the study. Hence, a larger community-based study including all types of acne is necessary to firmly establish the effect of personality disorders among acne patients. Furthermore, patients of Grade 3 and 4 acne are often managed with oral isotretinoin. In this study, we could not rule out the effect of isotretinoin on the psychological aspects of the study population.

CONCLUSION

The occurrence of anxiety, depression, and personality disorder is relatively higher among acne patients in comparison to that of the general population.

Psychiatrists often encounter patients with several dermatosis having some psychological disorders. Our study highlights that personality disorders and other psychiatric comorbidities are common in the setting of severe acne.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basavaraj KH, Navya MA, Rashmi R. Relevance of psychiatry in dermatology: Present concepts. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:270–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.70992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sathyanarayana Rao TS, Basavaraj KH, Das K. Psychosomatic paradigms in psoriasis: Psoriasis, stress and mental health. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:313–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.120531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koo JY, Smith LL. Psychologic aspects of acne. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:185–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1991.tb00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn LK, O'Neill JL, Feldman SR. Acne in adolescents: Quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spraker MK. Cutaneous artifactual disease: An appeal for help. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1983;30:659–68. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)34432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnold LM, McElroy SL, Mutasim DF, Dwight MM, Lamerson CL, Morris EM. Characteristics of 34 adults with psychogenic excoriation. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:509–14. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sneddon J, Sneddon I. Acne excoriée: A protective device. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1983;8:65–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1983.tb01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bach M, Bach D. Psychiatric and psychometric issues in acné excoriée. Psychother Psychosom. 1993;60:207–10. doi: 10.1159/000288694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallon E, Newton JN, Klassen A, Stewart-Brown SL, Ryan TJ, Finlay AY. The quality of life in acne: A comparison with general medical conditions using generic questionnaires. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:672–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasek RJ, Chren MM. Acne vulgaris and the quality of life of adult dermatology patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:454–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.4.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shuster S, Fisher GH, Harris E, Binnell D. The effect of skin disease on self image [Proceedings] Br J Dermatol. 1978;99(Suppl 16):18–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:846–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adityan B, Kumari R, Thappa DM. Scoring systems in acne vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:323–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.51258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loranger AW, Janca A, Sartorius N, editors. Assessment and diagnosis of personality disorders: The ICD-l0 international personality disorder examination (IPDE) First ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):20–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niemeier V, Kupfer J, Demmelbauer-Ebner M, Stangier U, Effendy I, Gieler U. Coping with acne vulgaris. Evaluation of the chronic skin disorder questionnaire in patients with acne. Dermatology. 1998;196:108–15. doi: 10.1159/000017842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Picardi A, Abeni D, Melchi CF, Puddu P, Pasquini P. Psychiatric morbidity in dermatological outpatients: An issue to be recognized. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:983–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malick F, Howard J, Koo J. Understanding the psychology of the cosmetic patients. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Ellis CN, Koblenzer CS. Psychiatric evaluation of the dermatology patient. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:591–9. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Schork NJ. Psychological factors affecting self-excoriative behavior in women with mild-to-moderate facial acne vulgaris. Psychosomatics. 1996;37:127–30. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(96)71578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasoulian M, Ebrahimi AA, Zare M, Taherifar Z. Psychiatric morbidity in dermatological conditions. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2010;14:18–22. doi: 10.3109/13651500903262370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ginsburg IH. The psychosocial impact of skin disease. An overview. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:473–84. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pattanayak RD, Sagar R. Depressive disorders in Indian context: A review and clinical update for physicians. J Assoc Physicians India. 2014;62:827–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reddy VM, Chandrashekar CR. Prevalence of mental and behavioural disorders in India: A meta-analysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:149–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maanasa TJ, Sivabackiya C, Srinivasan B, Ismail S, Sabari Sridhar OT, Kailash S. A cross sectional study on prevalence and pattern of personality disorders in psychiatric inpatients of a tertiary care hospital. IAIM. 2016;3:94–100. [Google Scholar]