Abstract

Background:

Patients are educated about their illness and its treatment at the time of diagnosis. However, little is known about how much of this education is retained and how it influences knowledge about, attitudes toward, and experiences with medication in antidepressant-naive patients with depression.

Methods:

Antidepressant-naive outpatients with International Classification of Diseases-10 dysthymia or mild to moderate depression, who were advised antidepressant monotherapy, were randomized to control (n = 22) or intervention (n = 17) groups. Control patients received treatment as usual, and intervention patients received, in addition, a face-to-face, individualized, 10-min education session about the nature of depression, antidepressant treatment, efficacy and adverse effects of the prescribed drug, and plan of management. Knowledge about the illness and its treatment were assessed at baseline (before the educational intervention) and 6 weeks later. At follow-up, experiences with treatment were also evaluated. The study was double-blind.

Results:

At baseline, patients had poor knowledge about their illness and its treatment (most patients could not even name their diagnosis); however, few held unfavorable attitudes toward their prescribed medicines. At follow-up, there were modest improvements in both sets of outcomes. There were no differences between intervention and control groups in knowledge and attitude outcomes at baseline and end-point. Drug compliance did not differ between groups. However, importantly, intervention patients experienced a significantly larger number of adverse events than controls (mean, 3.5 vs. 1.7, respectively).

Conclusions:

For ethical reasons, patients need to be educated about their illness and its treatment. However, such education may be a two-edged sword, with an increased nocebo effect as the most salient consequence. Failure to identify benefits in our study may have been the result of a Type 2 error. This study provides a wealth of information on a large number of issues related to knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of depressed, mostly low-income outpatients in relation to education about depression and its treatment, and future research can build on the findings of this study. We also provide an extensive discussion on directions for further research.

Key words: Adverse effects, antidepressants, attitudes, depression, education, experiences, knowledge

INTRODUCTION

Patients diagnosed with depression need to be educated about the nature of their illness and its management. This is an ethical requirement; it forms the basis for the therapeutic relationship, allows the patient to make rational decisions regarding treatment and course of life, and improves treatment adherence and follow-up, among other matters.[1,2] Psychoeducation (PE) can enhance patient confidence in the treatment and can prove to be a nonspecific factor that boosts the placebo effect in pharmacotherapy.[2] Furthermore, most patients harbor myths about the nature of depression and antidepressant drugs; these can be identified and resolved during PE sessions.

PE and its efficacy is a neglected subject in depression research in India. There is little information about the beliefs that patients have about their illness and antidepressant medications. This is especially a problem because patients are often not well educated and commonly harbor myths peculiar to their culture. Most important of all, there is no information about how much patients retain after having been provided with information during the initial session.

Heavy caseloads in conventional clinical care limit the time that mental health professionals can spend in PE. It is hence necessary to develop time-cost-energy PE programs for clinical practice in India and to evaluate the performance of such programs. This study was, therefore, conducted with the following general objectives:

To assess how much patients really know and understand about their illness and its treatment after their initial consultation for current depression

To develop a brief educational module about depression and its treatment with antidepressant medications and to determine whether the administration of this module has measurable and favorable effects on knowledge, attitudes, medication compliance, and experiences of depressed patients as assessed at a 6-week follow-up.

In this context, we emphasize that our study differed substantially in nature and objectives from educational and psychosocial interventions (in depression and related disorders) that address health outcomes, such as the landmark study of Patel et al.[3] in Goa, India.

METHODS

Setting

This randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted in the Departments of Nursing, Psychiatry, and Psychopharmacology at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore. The study was approved through a review process coordinated by the Departments of Nursing and Biostatistics, with attending experts from ancillary departments in the institute. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study; the consenting procedure did not provide information that would allow participants to guess to which group they were randomized.

Patients

Patients were drawn from the Screening Block, NIMHANS, where patients are seen at first contact with the hospital. All patients who were diagnosed with depression and who fulfilled the study selection criteria were invited to participate in the study after they had completed their consultation and received their prescription.

Patients were included if they met the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) criteria for mild depression, moderate depression, or dysthymia; all diagnoses were made by residents in psychiatry and were confirmed by a senior member of the unit on duty on that day. Additional inclusion criteria were age 18–60 years, residence within the catchment area of the hospital, ability to sit through a 30–60 min interview during which the study procedures were conducted, prescription containing antidepressant monotherapy, and a 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score of 12–23. Patients were excluded if they had significant medical or psychiatric comorbidities that might have confounded the diagnosis or prognosis or that might have affected their ability to understand and retain information provided during the study. Other exclusion criteria were antidepressant exposure during the past year and pregnancy and lactation.

Study procedure

Patients who consented for the study were randomized into PE and treatment-as-usual (TAU) groups using a preselected random number sequence obtained from a published source. Patients were then assessed, after which they were exposed to the educational module or its control equivalent.

Assessments

Patients were assessed using two instruments: The 17-item HAM-D and a knowledge, attitudes, and experiences (KAEs) questionnaire that was based on a previously validated instrument[4] and specifically adapted, after face validation, for the present study.

The KAE questionnaire comprised 71 items: Nine addressing sociodemographic variables, five addressing background clinical variables, 14 addressing knowledge, 23 addressing attitudes, 17 addressing experiences (including adverse effects [AEs]), and three addressing compliance.

These instruments were administered at baseline, before exposure to the PE module (or its TAU equivalent). These instruments were administered once again at a 6-week (±1 week) follow-up.

Educational module

The educational module was administered by an experienced clinician to patients in the experimental group. Besides the patient, the attending relative(s), if available, also participated in the educational session. All sessions were individualized; that is, patients were seen individually and not in groups.

The module was manual-driven with detailed instructions set out regarding content and delivery. The contents were explained using clear and simple language that the recipients could understand without difficulty.

The module provided an explanation about what depression is and about biological and environmental causes of depression; the concepts were simply presented, with the help of examples, for patients to understand influences related to genes, chemical changes, and stress. Psychological, social, biological, and other symptoms of depression were described. Depression was compared with medical illnesses to explain why antidepressant drugs help the condition.

Antidepressant drugs were discussed with regard to efficacy, timelines for response, AEs (with special reference to the antidepressant prescribed), and pertinent warnings (e.g., related to pregnancy and manic switch). The importance of medication adherence and the likely duration of treatment were both emphasized. Common myths about antidepressants were dispelled.

The duration of the educational session was approximately 10 min. At the end of the session, the patient and relative(s) were encouraged to seek clarification for whatever doubts they still had.

Patients who were randomized to TAU were asked about their symptoms. Afterward, their prescription was explained to them and they were encouraged to take their medicines as advised. No PE was provided, and the session lasted about 5 min. To ensure uniformity of interactional characteristics, the same clinician conducted all sessions for patients in both experimental and control groups.

Blinding

Patients knew that they were participating in a study that assessed KAEs with antidepressant drugs. They were unaware of the nature of the content of the intervention sessions and so would have been unaware of treatment assignment. The rater who administered the KAE questionnaire was a trained psychiatric nurse who did not know the group to which the patients had been assigned. Thus, the study was double-blind.

Statistical analysis

This study was planned as pilot, proof-of-concept investigation and it was decided to recruit twenty patients in each treatment arm. Neither primary outcome variable was set nor was sample size pre-estimated. A completer analysis was conducted on the follow-up data because the investigation was intended to identify areas for attention in larger follow-up studies.

Continuous variables were compared between groups using the independent sample t-test and across time using the paired t-test; where data were not normally distributed, the Mann–Whitney test was applied, correcting for ties. Categorical data were compared between groups using the Chi-square and Fisher's exact probability (FEP) tests. Correlations were determined using the Pearson and Spearman procedures. Changes across time were compared between groups using two-way repeated measures analysis of variance, examining only the interaction between variables in a completer analysis.

All tests were two-tailed. Alpha for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05; because of the exploratory nature of the study, no corrections were applied for multiple statistical testing.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

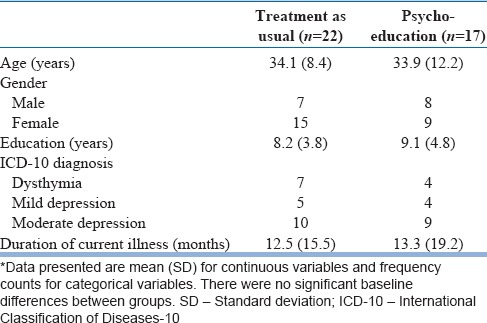

The sample comprised 39 patients, randomized to TAU (n = 22) or PE (n = 17) groups. The mean age of the sample was 34 years and the sample was 62% female. Although 69% of the sample comprised semi-skilled (which category was assigned to housewives, as well) or skilled persons, all but two fell into low-income categories (income <Rs. 10,000 per month). Whereas 62% of the sample was married, only two patients resided alone. Dysthymia accounted for 28% of the sample; the remainder had ICD-10 mild or moderate depression. Only four patients had previous antidepressant exposure (two in each group). A brief sociodemographic and clinical description of the sample is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical description of the sample*

Six patients dropped out of treatment from the TAU group and seven from the PE group (Chi-square, 0.83; df = 1; P = 0.36).

Baseline knowledge

At baseline, 49% of patients were satisfied with the information that their doctor had provided them about their illness; however, only 23% were satisfied with the information that they had received about their medication. Surprisingly, only two patients were able to state depression as their diagnosis; 72%, in fact, provided no meaningful answer or a wrong answer to the question about their diagnosis.

The average patient was able to name five symptoms of his/her illness. Almost all patients (92%) identified one or more stressors as the cause of the illness. Interestingly, a quarter of the sample offered explanations unrelated to stress, such as black magic, or their fate. Only four patients suggested that there might be biological explanations for their illness.

Only one patient knew the name of the medicine that was prescribed. Surprisingly, only five patients could correctly state how their medicine was supposed to be taken with regard to dose and time of day. Two patients were able to suggest that their antidepressant would work by chemical action in their brain. Almost all patients considered that the medicine would begin to act after a few days or weeks. With the exception of 6 patients (15%), all realized that it could take weeks to months for them to recover from the illness. However, only six patients (15%) identified a likely duration of treatment (at least 6 months).

The TAU and PE groups did not differ significantly in their baseline knowledge of their illness and its treatment.

Baseline attitudes

On a visual analog scale (0–10), patients scored marginally >6 as their estimate of the importance of medicines in the treatment of their illness. On a visual analog scale ranging from -5 (“I can overcome my illness without the use of drugs”) to + 5 (“drugs are very important for my illness”), patients scored + 2, indicating a reasonable recognition of the importance of medical treatment.

Two patients reported that their psychiatric consultation resulted in alarm rather than in reassurance. Surprisingly, despite the bad press that psychiatric medicines receive, only five patients (13%) were afraid that their medicines were sleeping pills; however, 9 (23%) thought that the medicines might be habit forming. A small but clinically significant number of patients admitted to a fear of early onset (26%), late onset (21%), or permanent (15%) AEs with medication use. However, only two patients thought that medications may make their illness worse.

Fears about medication arose spontaneously in 26% of patients; as a result of AEs of other drugs in 13%; as a result of exposure to visual or printed media (one patient, each); and from interactions with other patients (15%). No patient reported anxieties about medications resulting from internet sources.

On a visual analog scale (0–10), patients rated slightly over seven as their confidence that their doctor had understood their problem and as their confidence that their medicine would help them recover.

The TAU and PE groups did not differ significantly in their baseline attitudes toward their illness and its treatment.

Knowledge at follow-up

There was a substantial improvement in recognition of the psychological nature of the illness at the 6-week follow-up, with 73% of patients stating a psychological expression or specifically naming depression; however, patients were able to name only four symptoms of their illness, on average. This represented a small and statistically significant (but clinically unimportant) decrease from baseline (F = 4.66; df = 1.24; P = 0.041).

At follow-up, almost all patients (85%) identified stress as a cause of their illness; no patient offered reasons unrelated to stress, but only a quarter of the sample endorsed a biological explanation.

Surprisingly, only four (15%) patients were able to name their antidepressant. However, all but two patients were able to provide a reasonable explanation about how their medication was dosed. Whereas 60% of the PE patients endorsed a biological mechanism of action for their medication, only one TAU patient did so; the remaining TAU patients thought that the medication acts by improving specific symptoms such as sleep.

Half of the PE group and 38% of the TAU group recognized that they would probably require to continue their medication for at least 6 months.

Statistical testing between groups was not possible because the data violated the expected frequency requirement for contingency table testing; however, on visual evaluation, there was little difference in percentages between groups.

Attitudes at follow-up

On a visual analog scale (0–10), patients scored a mean (standard deviation (M [SD]) of 6.4 (3.2) versus 6.6 (3.6) in the PE versus TAU groups, respectively, as their estimate of the importance of medicines in the treatment of their illness. On a visual analog scale ranging from -5 (“I can overcome my illness without the use of drugs”) to + 5 (“Drugs are very important for my illness”), patients scored 3.9 (1.1) versus 2.9 (2.1).

Importantly, only one patient was concerned that the medication might be habit forming; only two thought that the medication may cause permanent AEs; no patient was worried that medication may make illness worse; and only four patients were afraid that their medications may be sleeping pills. On a visual analog scale (0–10), patients scored 7.3 (3.1) versus 6.3 (3.8) in PE and TAU groups, respectively, as their confidence that their medicine would help them recover.

The experience of benefit influenced attitudes toward medication in 90% versus 75% of PE versus TAU patients, respectively. However, the experience of AEs influenced attitudes in 80% versus 18.8% of patients in the two groups (Fisher's exact P = 0.004). Notwithstanding, 70% versus 62.5% of patients reported that experience of benefits most influenced their attitudes toward medication; this figure was 20% versus 18.8% for the experience of AEs, and 10% versus 18.8% for interactions with a health-care professional. Interestingly, no patient reported that other patients or the mass media influenced their attitudes.

Patients who expressed happiness that medication was available to treat their illness accounted for 70% versus 50% in PE versus TAU groups, respectively; one PE and three TAU patients were unhappy with their medication, apparently because of insufficient benefit. No patient definitely viewed medication as a curse that they had to bear.

Unless specifically stated otherwise, the PE and TAU groups did not differ significantly in any of these regards.

Experiences at follow-up

At the 6-week follow-up, 100% of the PE and 75% of the TAU groups considered that they had benefited from drug treatment; the difference was not statistically significant (FEP = 0.14). In each group, patients considered that it took about 10 days for the medicine to begin to help. AEs reported in the PE versus TAU groups were disturbed sleep (40% vs. 37.5%), disturbed appetite (10% vs. 40%), general physical complaints such as headache, body ache, and weakness (50% vs. 6.3%), general mental complaints (10% vs. 0%), general mood complaints (20% vs. 12.6%), gastrointestinal complaints (50% vs. 12.5%), sexual complaints (10% vs. 0%), motor disturbances (10% vs. 6.3%), skin complaints (30% vs. 6.3%), and miscellaneous complaints (30% vs. 25%). Among women, 1 of 4 in the PE group and 1 of 9 in the TAU group reported gender-specific complaints.

On a visual analog scale, PE patients reported greater AE-related impairment in happiness and quality of life (mean, 3.8 vs. 0.8, respectively; P < 0.01). On a visual analog scale, PE and TAU patients reported minimal AE-related interference in daily activities (means, 1.9 vs. 0.9, respectively; P = 0.16). Both PE and TAU patients reported that benefits outweighed AEs related to treatment; the scores in the two groups were almost identical. Three (30%) PE patients and no (0%) TAU patients were unwilling to accept their present degree of AEs so that they could continue to experience the medication-related benefits.

Compliance

Many PE and TAU patients (30% vs. 37.5%; P = 1.00) thought that they could skip medication doses sometimes or even often, without problems. PE patients knowingly missed doses more often than TAU patients (means, 4.5 vs. 2.1; P = 0.39) but forgot to take doses less often (means, 0.8 vs. 2.8; P = 0.12); neither difference was statistically significant.

Knowledge, attitude, and adverse effect subscale analyses

Items were combined from the KAE sections of the KAE questionnaire to obtain knowledge, attitude, and AE subscales, respectively, with higher scores indicating greater knowledge, more negative attitudes, and more AEs.

The M (SD) knowledge score in the PE versus TAU groups was 6.7 (1.7) versus 6.7 (0.9), respectively, at baseline (t = 0.05, df = 23, P = 0.96), and 7.5 (1.5) versus 6.5 (0.8), respectively, at 6 weeks (t = 1.93, df = 12.4, P = 0.08). Change in knowledge did not differ significantly between groups across the course of the study (F = 2.68, df = 1.24, P = 0.12).

The M (SD) attitude score in the PE versus TAU groups was 1.4 (2.6) versus 2.0 (3.0), respectively, at baseline (z = 0.77, P = 0.44), and 1.7 (2.4) versus 0.6 (1.0), respectively, at 6 weeks (z = 1.13, P = 0.26). Change in attitudes did not differ significantly between groups across the course of the study (F = 0.20, df = 1.24, P = 0.66).

Patients experienced 3–18 and 0–12 AEs in the PE and TAU groups, respectively; the M (SD) were 3.5 (2.6) versus 1.7 (1.9). There were significantly more AEs in the PE group (z = 2.02; P = 0.044).

In exploratory analyses, AEs showed no significant correlation with age, education, income, or duration of illness. AEs also did not differ significantly as a function of gender, occupational skill, marital status, or depression type.

DISCUSSION

In this pilot, proof-of-concept RCT, we sought to understand the patients' knowledge about and attitudes toward their illness and its treatment before and 6 weeks after initiating treatment. We also sought to examine the effects of a brief, manual-driven PE intervention on KAEs related to depression and its treatment; the importance of manualization is that replicability and generalization are enhanced. We obtained a wealth of information about what poorly educated, low-income patients know and think about depression and its treatment, and our findings and experiences in this study can serve as a springboard for future efforts in the field.

The first important though unexpected finding in this study is that the personalized PE program, although comprehensive in scope, did not seem to have made a greater impact than TAU on patient knowledge and attitudes. One explanation for the finding is that the program was brief; perhaps something that is practical and brief enough to be suitable for clinical contexts in India may not be adequate to meet the educational needs of the average patient. Another explanation, and a more likely one, is that at the initial consultation, patients are preoccupied with stressors and their depression, and so they do not retain much; and depression-related cognitive impairments[5] may compromise comprehension and retention of technical information. Furthermore, patients would have been unfamiliar with the concepts being explained, and this could have further compromised their ability to acquire and retain knowledge. Finally, normal forgetting after 6 weeks could have diminished the impact of the education provided. The bottomline is that the initial PE session is insufficient; materials discussed during the initial session require to be reviewed in subsequent sessions if PE is to be clinically useful.

The next important finding in this study was that the PE group experienced a larger number of AEs. This was not an artifact of reporting because, in this study, we systematically enquired about adverse events associated with antidepressant treatment, and so the larger number of adverse events identified in the PE group was not a result of biased spontaneous reporting resulting from greater awareness. It was not due to better compliance, either because compliance did not differ significantly between groups. There are two possible interpretations of this outcome. One is that the PE patients were more aware of adverse events and therefore looked out for them and remembered them better. That is, patients knew what to look for and what to report; and when they experienced the adverse event, it reinforced the memory. However, this does not explain why TAU patients forgot the AEs if the AEs occurred with equal frequency. Therefore, the other and more likely possibility is that briefing patients about AEs primes them for a nocebo effect. There is some support for the latter explanation in literature; Kaptchuk and Miller[6] observe that telling patients about drug AEs increases the likelihood of those AEs. In addition, AEs commonly identified in medication trials are specific to the AE profile of the trialed drugs and not to the AE profile of other drugs; this also suggests a nocebo effect arising out of knowing what to expect.[6]

It would not be ethical to conceal the risk of AEs in PE sessions. However, there are two ways in which a nocebo effect can be diminished during PE:

The health-care professional can emphasize the mildness and infrequency of the AEs, as appropriate, priming the patient to the likelihood that the AE is unlikely as opposed to the AE being possible. This is a reasonable approach, given that most drugs have a favorable risk-benefit ratio. In this approach, also, coping strategies can be taught that will help the patient deal with the AE should it occur. Empowering the patient could provide confidence and thereby diminish the likelihood of a nocebo response

Instead of itemizing the AEs, the health-care professional can make a generic statement that most patients do not have AEs; or, if AEs occur, they are mild and untroubling. Should the patient experience an event of concern, she/he can get in touch with the treatment team. This approach is more controversial and cannot be adopted when there are AEs of importance, such as the risk of sedation or weight gain. However, this approach has its advantages in that it dispenses with the recitation of a laundry list of possible AEs that are unlikely to occur but that will certain alarm patients, especially those who are already anxious and depressed.

Both of the options suggested above require empirical study. Strategies to diminish the nocebo effect were also suggested by Bingel.[7] We do not discuss the remaining findings of our study because, being descriptive in nature, these are readily apparent from the text and tables, and because our study was a pilot, proof-of-concept investigation that was intended to guide future research.

Limitations and guidance for future research

Our study had several limitations. The sample size was small because this was a pilot, proof-of-concept RCT, and therefore many analyses would have been underpowered to detect significance in the many trends that emerged favoring PE over TAU; nevertheless, the trends observed provide guidance for areas meriting future attention.

The sample was drawn from a tertiary care, government hospital; patients mostly belonged to lower socioeconomic strata and the average patient had not completed schooling. Therefore, the findings of the study cannot be generalized to more educated patients from higher socioeconomic strata. It is possible that patients from different socioeconomic strata would need differently constructed and administered PE programs.

Baseline attitudes toward medication seemed generally favorable. We do not know whether this was the result of a Hawthorne effect[8] where patients provided socially acceptable responses; this, therefore, requires special attention in future studies.

We did not record data about the antidepressants that patients received and the dose that was advised; dose and drug could separately and together have influenced attitudes and experiences; this will need to be addressed in work that builds on the current study. Individual patient data on baseline depression severity were unavailable to assess whether this variable influenced the outcome measures in the study. Depression severity was not rated at follow-up; treatment nonresponse could have confounded end-point attitudes. It may also be desirable for future studies to separately analyze data from patients with dysthymia and those with mild to moderate (major) depression because these two disorders are qualitatively different.

Additional possibilities that can be considered in future include starting the session by allowing patients to ask questions; involving the family in the PE; performing subgroup analyses based on prespecified categories (e.g. defined by diagnosis or socioeconomic status, or prior exposure to medication, or prior adverse experiences with healthcare systems); and obtaining end-point data from patients who drop out of treatment (because reasons for drop out are unlikely to be random). Finally, important confounds can be included as covariates in adequately powered analyses that compare PE with TAU.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Channabasavanna SM. Drug therapy in India: Critical issues in the quality of care. Indian J Psychiatry. 1996;38:67–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mintz DL, Flynn DF. How (not what) to prescribe: Nonpharmacologic aspects of psychopharmacology. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35:143–63. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, Naik S, Pednekar S, Chatterjee S, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:2086–95. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61508-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bopanna KN. Knowledge about, Attitudes Towards, and Experiences with Antidepressant Drugs in an Indian Setting. PhD Thesis. Bangalore: National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Culpepper L. Impact of untreated major depressive disorder on cognition and daily function. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:e901. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13086tx4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaptchuk TJ, Miller FG. Placebo effects in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:8–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1504023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bingel U. Placebo Competence Team. Avoiding nocebo effects to optimize treatment outcome. JAMA. 2014;312:693–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrade C. There's more to placebo-related improvement than the placebo effect alone. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1322–5. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12f08124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]