Abstract

T follicular helper (TFH) cells have been shown to be critically required for the germinal center (GC) reaction where B cells undergo class switch recombination and clonal selection to generate high affinity neutralizing antibodies. However, detailed knowledge of the physiological cues within the GC microenvironment that regulate T cell help is limited. The cAMP-elevating, Gs protein-coupled A2a adenosine receptor (A2aR) is an evolutionarily conserved receptor that limits and redirects cellular immunity. However, the role of A2aR in humoral immunity and B cell differentiation is unknown. We hypothesized that the hypoxic microenvironment within the GC facilitates an extracellular adenosine-rich milieu, which serves to limit TFH frequency and function, and also promotes immunosuppressive T follicular regulatory cells (TFR). In support of this hypothesis, we found that following immunization, mice lacking A2aR (A2aRKO) exhibited a significant expansion of T follicular cells, as well as increases in TFH to TFR ratio, GC T cell frequency, GC B cell frequency, and class switching of GC B cells to IgG1. Transfer of CD4 T cells from A2aRKO or wild type donors into T cell-deficient hosts revealed that these increases were largely T cell-intrinsic. Finally, injection of A2aR agonist, CGS21680, following immunization suppressed T follicular differentiation, GC B cell frequency, and class switching of GC B cells to IgG1. Taken together, these observations point to a previously unappreciated role of GS protein-coupled A2aR in regulating humoral immunity, which may be pharmacologically targeted during vaccination or pathological states in which GC-derived autoantibodies contribute to the pathology.

Keywords: adenosine, adenosine receptor, cyclic AMP (cAMP), hypoxia, vaccine, vaccine development, A2a adenosine receptor (A2aR), T follicular helper (TFH) cell, T follicular regulatory (TFR) cell, germinal center (GC), class switch recombination (CSR)

Introduction

Novel vaccination strategies to elicit high affinity broadly neutralizing antibodies to difficult immunogens such as HIV-1 and influenza require detailed investigation into the physiologically relevant, evolutionarily conserved mechanisms that control humoral immunity. Ideally, such mechanisms that are easily pharmacologically targetable would be of particular value for vaccine design. Although work in recent years has yielded much new knowledge about the role of specific transcription factors and surface ligands that regulate humoral immunity (1–4), there have been somewhat fewer studies investigating the role of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)3 in regulating this process (5–8). In terms of the potential for modulating the vaccine response, GPCRs have the considerable advantage of often being readily targetable by small molecules, and thus represent one of the most studied and highly used classes of drugs in medicine (9).

The germinal center (GC) is the microanatomic site where activated B cells undergo class switch recombination, somatic hypermutation, and clonal selection to produce effective, long lived antibody responses following vaccination (1, 10). The GC reaction has been shown to be critically dependent on T follicular helper cells (TFH), which provide help to B cells through a variety of surface molecules such as ICOS (inducible costimulator) and CD40 ligand (CD40L) and by soluble cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-21, as well (11). TFH have been shown to be limiting for both entry into the GC as well as for GC maintenance and affinity maturation during the iterative process of somatic hypermutation and clonal selection (2, 3). Studies of mechanisms that regulate the GC have led to the identification of a relatively new subset of T regulatory (Treg) cells, T follicular regulatory cells (TFR) (12, 13), which have been shown to limit the GC reaction partially through the action of the inhibitory receptor CTLA-4 (14, 15).

The A2a adenosine receptor (A2aR) has been shown to be a cyclic AMP-elevating, GS protein-coupled GPCR that can limit cellular immunity in vivo in multiple murine models of inflammation (16, 17) and anti-tumor responses (18). Additional evidence has shown that the role of A2aR in limiting inflammation appears to be phylogenetically conserved on human T cells (19–21). Functionally, A2aR has been shown to be expressed at higher levels on differentiated human Th1 and Th2 cells that produce cytokines (19). However, the role of A2aR in regulating humoral immunity following vaccination or infection has remained largely unexplored.

We recently reported that the GC develops a hypoxic microenvironment that promotes B cell differentiation (22). Because hypoxic microenvironments are also often rich in extracellular adenosine (“hypoxia-adenosinergic”) (17), we hypothesized that the hypoxic GC develops an adenosine-rich microenvironment that could serve to regulate local T cell help through A2aR. We show here that A2aR is indeed required for maintaining normal frequencies of TFH, TFH/TFR ratios, and the overall ratio of T to B cells in GCs. Additionally, we found that A2aR deletion results in increased frequencies of GC B cells and class switching to IgG1 within GCs. Utilizing a T cell transfer model, we determined these observed differences to be due largely to A2aR signaling specifically on CD4 T cells. Lastly, in excellent correlation with these determinations, we found that pharmacological stimulation of the A2aR from days 2 to 8 following primary vaccination led to significant decreases in the frequency of GC B cells and T follicular cells as well as reduced class switching of GC B cells to IgG1.

Results

T Follicular Cells Have the Potential to Generate Extracellular Adenosine and Express Functional A2aR

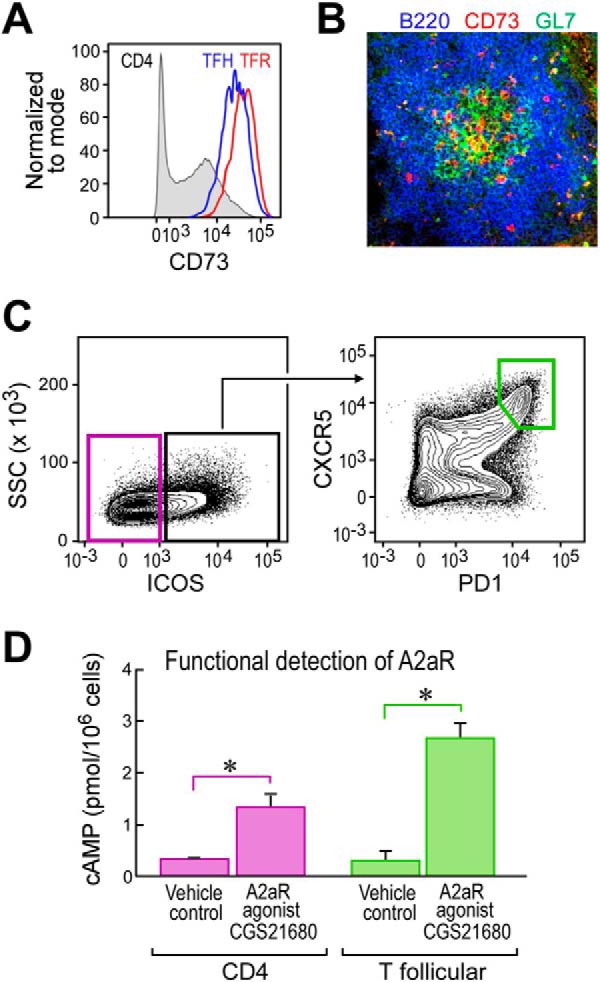

To ascertain whether the GC comprises regions of high extracellular adenosine (exAdo), we looked for a proxy for adenosine generation as direct measurement of exAdo via equilibrium microdialysis probes is not technically feasible. Expression of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked ecto-enzyme 5′-nucleotidase (CD73), which catalyzes the degradation of AMP to adenosine (17, 23), is often up-regulated in hypoxic conditions (17, 24–27). Therefore, in lieu of direct exAdo measurements, we assessed whether CD73 was up-regulated on TFH and TFR as defined by the diagnostic CD4+,B220−,CXCR5+, PD-1+, FoxP3− and CD4+, B220−, CXCR5+, PD-1+,FoxP3+ phenotypes, respectively. We found that CD73 is highly expressed on both TFH and TFR (Fig. 1A), consistent with other groups showing high expression on T follicular cells (28). Because a clear definition of GC TFH by flow cytometry in mouse is somewhat difficult, we opted to directly stain GCs for CD73 by immunohistology in situ to assess whether CD73 was detectable within GCs. We found prominent expression of CD73 by a subset of cells within the GCs (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

T follicular cells demonstrate capacity for A2aR signaling. A, representative flow cytometric plot 8 days following i.p. NP-OVA/alum immunization depicting CD73 expression on total CD4 T cells, TFH gated as CD4+, B220−, CXCR5+, PD-1+, Foxp3−, and TFR gated as CD4+, B220−, CXCR5+, PD-1+, Foxp3+. B, histological analysis of a splenic germinal center 12 days following i.p. immunization with NP-OVA/alum staining for B220 (blue), GL7 (green), and CD73 (red). The image was taken using a 20× objective. C, sort layout for CD4 and T follicular CD4 T cells gated as scatter, singlet, live, CD19−,CD11c−, GR-1−, CD8−, CD4+, TCRβ+. D, ELISA results from cAMP induced following stimulation with CGS21680 of sorted T follicular or CD4 T cells. *, p < 0.05. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. ELISA wells were run in duplicate.

With the observation that the GC is likely under the influence of the hypoxia adenosinergic pathway, we next assessed whether A2aR is prominently expressed on T follicular cells. Due to the fact that there is no reliable monoclonal antibody for detecting mouse A2aR via flow cytometry, we opted to purify T follicular cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting and then stimulate the cells with A2aR-specific agonist CGS21680 (CGS) in vitro and measure downstream cAMP induction. We found that both control CD4 T cells and to a greater extent T follicular cells showed increases in cAMP upon A2aR stimulation, indicative of functional A2aR expression (Fig. 1, C and D).

The A2a Adenosine Receptor Regulates T Follicular Cells and GC B Cells following Immunization

To test our hypothesis that exAdo in the GC regulates the GC via the A2aR, we chose to immunize A2aR-deficient mice (A2aRKO) i.p. with the hapten-protein conjugate, 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl(acetyl) ovalbumin (NP-OVA), precipitated in aluminum hydroxide adjuvant (alum), and assessed the induction of splenic T follicular cells 12 days after immunization. By flow cytometric analysis, we found that A2aRKO mice exhibited significant increases in the frequency of T follicular cells as defined by either CD4+,CD8−,CXCR5+, PD-1+, or CD4+,B220−, CXCR5+, BCL-6+ phenotypes (Fig. 2, A and B) when compared with C57Bl/6J WT controls. Furthermore, we determined that naive unimmunized A2aRKO mice housed in our specific pathogen-free vivarium contained no appreciable perturbations in major lymphocyte population or the frequency of naive CD4 T cells capable of responding to immunization (supplemental Fig. S1).

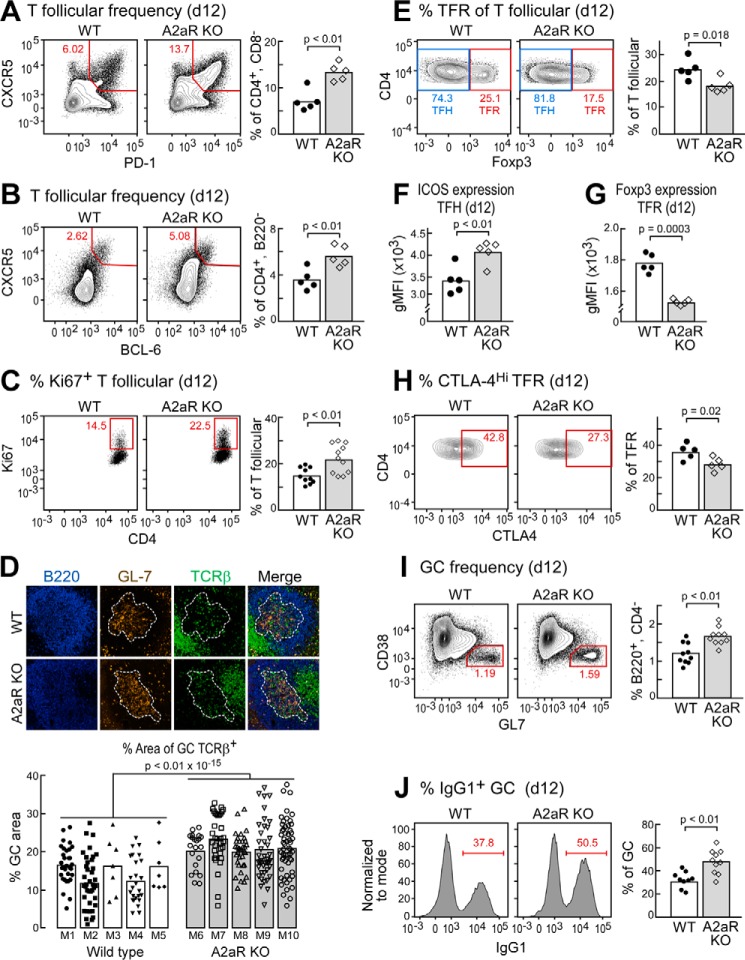

FIGURE 2.

The A2a adenosine receptor regulates T follicular cells and GC B cells following immunization. A and B, representative flow cytometric plots of splenic T follicular cells of WT or A2aRKO mice immunized i.p. with NP-OVA/alum 12 days following immunization. Cells were gated as scatter, singlet, live, CD4+, B220−. C, Ki-67 expression of cells described in A, gated as scatter, singlet, live, CD4+, B220−, CXCR5+, PD-1+. D, histological analysis of GCs on day 12 as described in A of WT or A2aR KO mice (upper). Quantification of TCRβ+ cells within the germinal center from 5 mice per group was as follows: n = 189 GCs analyzed for A2aRKO, and n = 113 GCs for analyzed WT. Each bar represents one mouse, each dot represents one GC. E, Foxp3 staining of cells gated as in C to identify TFR and TFH. F, ICOS expression of TFH gated as scatter, singlet, live, CD4+, B220−, CXCR5+, PD-1+, Foxp3−. G and H, expression of Foxp3 and CTLA-4 on TFR as defined by scatter, singlet, live, CD4+, B220−, CXCR5+, PD-1+, Foxp3+. I, GC frequencies of WT or A2aRKO mice as defined by scatter, singlet, live, CD4−, B220+, CD38−, GL7+. J, IgG1+ cells within the GC gated cells were defined as in I. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments containing 5–10 mice per group. Images were taken using a 20× objective.

Consistent with the increase in frequencies of T follicular cells, we noted a significant increase in the frequency of T follicular cells in A2aRKO mice that expressed the proliferation marker Ki-67 (Fig. 2C). To determine whether the increase in T follicular cells was reflected in the proportion of T cells within the GC, we performed immunohistology to quantify T cells in GCs. Indeed, we found a significant increase (p < 0.01 × 10−15) in the fraction of TCRβ+ cells contained within the GC areas as determined by GL-7 and B220 staining (Fig. 2D).

Because the T follicular compartment (CD4+,B220−,CXCR5+, PD-1+) contains both TFH and TFR, we wanted to determine whether our observed increases in T follicular cells in A2aRKO mice were a proportional increase between the two populations, or whether either population was more favorably expanded. To distinguish TFH from TFR, we utilized the detection of the transcription factor Foxp3, thus defining TFR as CD4+,B220−,CXCR5+, PD-1+, Foxp3+ and TFH as CD4+, B220−,CXCR5+, PD-1+, Foxp3−. In this way, we found that A2aRKO mice exhibit a significant increase in the proportion of TFH to TFR (Fig. 2E), showing reduced relative frequency of TFR. Taken together with our data showing expansion of T follicular cells (CD4+,B220−,CXCR5+, PD-1+), this relative reduction in TFR frequency suggests that A2aR deficiency allows for selective expansion of the TFH population.

We next sought to determine whether A2aR deficiency affected functional aspects of TFH and TFR. Further investigation into the activation state of TFH revealed that TFH in A2aR KO mice exhibited increased expression level of the co-activator ICOS (Fig. 2F), which is critical for TFH development (29) and is one mechanism by which TFH provide help to GC B cells (2).

Due to the fact that A2aR signaling is known to promote the function of conventional Treg (30), and TFR are thought to arise from natural Treg (12, 13), we hypothesized that A2aR may have a similar function on TFR by potentiating TFR regulatory capacity. Analysis of the TFR population revealed a significant decrease in Foxp3 expression level in A2aRKO mice (Fig. 2G), suggesting the possibility that A2aRKO TFR may have reduced suppressive ability. To investigate this notion further, we determined the level of CTLA-4 expression on TFR in A2aRKO mice, as CTLA-4 expression has been specifically shown to be one of the mechanisms by which TFR suppress GC reactions (14, 15). In support of the hypothesis that A2aR signaling promotes TFR suppressive capacity, we found that A2aRKO mice had reduced expression of CTLA-4 on TFR (Fig. 2H).

Consistent with the observation of increased TFH frequencies and potential increase in T cell help capacity in A2aRKO mice, we investigated the GC compartment by flow cytometry as defined by B220+, CD4−, CD38−, GL-7+. Consequently, we found a small but statistical increase in frequencies of GC B cells in A2aRKO mice on day 12 following immunization (Fig. 2I). It is important to note that the increase we observed in GC B cells was not as substantial as the increases we observed within the T follicular compartment (Fig. 2, A and B), consistent with our histological analysis showing increased frequency of T cells within the GC (Fig. 2D). We next sought to investigate whether GC B cells were more functionally differentiated in A2aRKO mice. We observed that on day 12 following immunization, there was a greater proportion of class-switched IgG1+ cells within the GC B cell compartment in A2aRKO mice when compared with WT controls (Fig. 2J).

A2aR Deficiency in T Cells Leads to Expanded T Cell Help in the GC

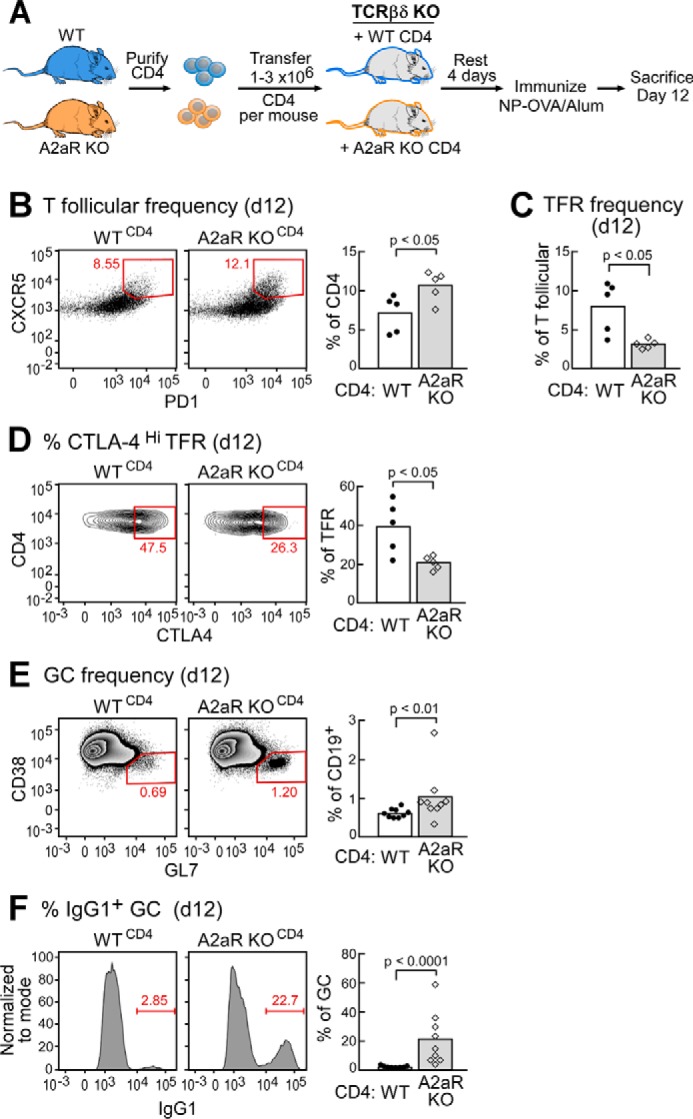

We next asked whether these functional effects could be specifically attributed to A2aR signaling directly in T cells. To answer this question, we purified CD4 T cells by magnetic depletion and transferred equal numbers of either WT or A2aRKO CD4 T cells into mice genetically lacking T cells (TCRβ/δ) KO mice, thus generating mice in which A2aR deficiency is specific to the CD4 T cell compartment (referred to as WTCD4 or A2aRKOCD4) (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

A2aR deficiency on T cells leads to expanded T cell help in the GC. A, schematic overview of experimental design. B, splenic T follicular frequencies on day 12 following immunization of WT or A2aRKO chimeric mice. Cells were gated as scatter, singlet, live, CD4+, B220−, CXCR5+, PD-1+. C and D, relative frequency of TFR defined as scatter, singlet, live, CD4+, B220−, CXCR5+, PD-1+, Foxp3+ and the proportion of TFR highly expressing CTLA-4 within the TFR gate. E, representative flow plots of GC B cells from WT or A2aRKO chimeric mice immunized as in A. Cells were gated as scatter, singlet, live, CD4−, B220+, CD38−, GL7+. F, frequency of IgG1+ cells within the GC gate of WT or A2aRKO chimeric mice as defined in E. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments containing 5–10 mice per group.

After resting the mice for 4 days, we immunized them with NP-OVA/alum i.p. as we did before and determined the frequencies of splenic T follicular and GC B cells 12 days following immunization (Fig. 3A). We determined by flow cytometry that A2aRKOCD4 mice showed significant increases in T follicular frequencies (Fig. 3B) as well as a reduced proportion of TFR to TFH (Fig. 3C), suggesting a preferential expansion of TFH in A2aRKOCD4 mice. We also observed decreases in CTLA-4 expression on TFR in A2aRKOCD4 mice (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these data suggest that increases in the potential for T cell help in total A2aRKO mice are largely due to lack of intrinsic A2aR signaling in CD4 T cells.

Consistent with this observation, we noted a small but statistically significant increase in GC B cell frequency in A2aRKOCD4 mice when compared with controls (Fig. 3E). Most strikingly, however, we found a nearly 10-fold increase in class switching of GC B cells to IgG1 in A2aRKOCD4 mice (Fig. 3F). This observation further supports the hypothesis that A2aR on CD4 T cells functionally limits T cell help to GC B cells.

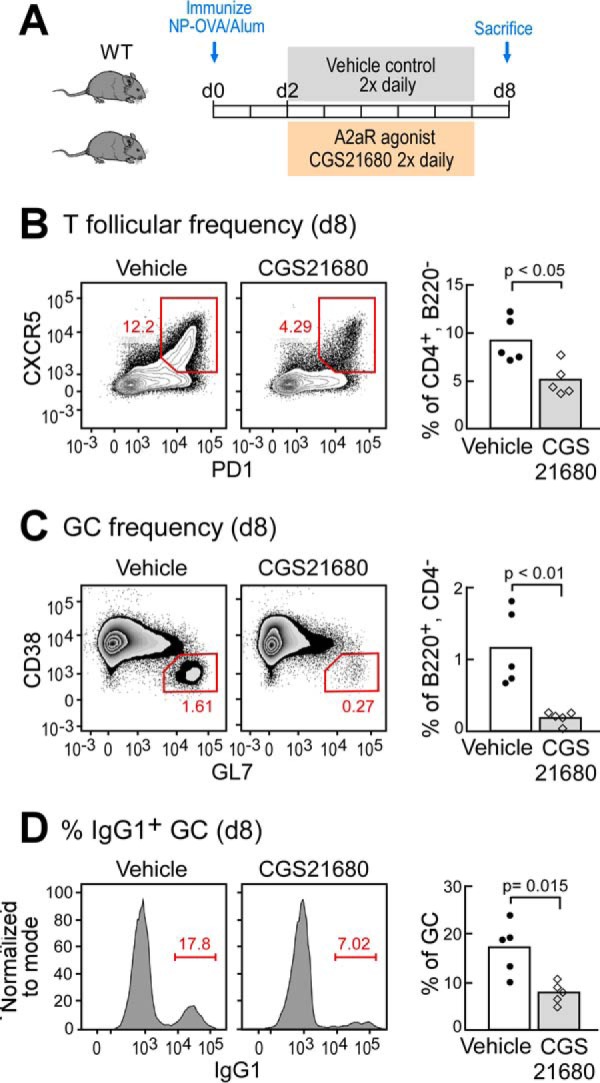

Stimulation of A2aR Suppresses T Follicular and GC Frequencies

Because we determined that A2aR signaling is required in regulating T follicular responses and GCs in vivo, we asked whether this pathway could be modulated by pharmacological manipulation following vaccination. To test this prediction, we immunized WT C57Bl/6J mice i.p. with NP-OVA/alum as before and administered the A2aR-specific agonist CGS twice daily starting from day 2 to day 8 following immunization (Fig. 4A). We found that splenic T follicular cells were significantly reduced on day 8 in mice treated with CGS when compared with vehicle control (Fig. 4B). Additionally, we found that the GC B cell population was significantly reduced in mice treated with CGS (Fig. 4C). Moreover, CGS-treated mice exhibited impairment in functional differentiation of GC B cells as evidenced by reduced frequencies of class-switched IgG1+ GC B cells (Fig. 4D). Consistent with our data from A2aRKO and A2aRKOCD4 mice, the results from our studies utilizing CGS indicate that extracellular adenosine signaling through A2aR serves to limit the GC reaction. Furthermore, these studies show that this pathway can be pharmacologically manipulated following vaccination.

FIGURE 4.

Stimulation of A2aR suppresses T follicular and GC frequencies. A, schematic overview of experimental design. B, frequency of splenic T follicular cells of WT mice on day 8 (d8) following immunization with NP-OVA/alum and treated with A2aR agonist CGS21680 two times daily (0.5 mg/kg) or vehicle control from days 2 to 8. Cells were gated as scatter, singlet, live, CD4+, B220−, CXCR5+, PD-1+. C, GC frequencies of mice treated as in B. Cells were gated as scatter, singlet, live, CD4−, B220+, CD38−, GL7+. D, frequency of IgG1+ cells within GCs of mice treated as in B and C, and gated as in C. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments containing 5–7 mice per group.

Discussion

Taken together, our data reveal a previously unknown role for extracellular adenosine signaling through A2aR in the regulation of GC responses. We found that following immunization, A2aR functions to limit the magnitude of TFH help and that both A2aRKO and chimeric A2aRKOCD4 mice exhibit increased T follicular and GC B cell frequencies as well as GC B cell class switching to IgG1 (Figs. 2 and 3). A2aR deficiency also revealed potential reductions in relative TFR frequencies and function via CTLA-4 expression in both A2aRKO and A2aRKOCD4 mice when compared with respective controls (Figs. 2, E and H, and 3, C and D). Reaffirming these observations for a clear role of A2aR signaling in regulation of GCs, we found that administration of A2aR-specific agonist CGS from days 2 to 8 following immunization led to significant decreases in T follicular frequencies, GC B cell frequencies, and GC B cell class switching to IgG1 (Fig. 4). Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that A2aR plays a key role in regulating T cell help within the GC.

While this investigation into the role of A2aR in regulating GC responses has provided evidence for a clear role for A2aR in regulating T follicular help within the GC, it is important to note both the limitations of our study and future directions. Although we show that A2aR intrinsically regulates CD4 T cell help in adoptive transfer studies (Fig. 3), it remains to be seen whether A2aR signaling is most critical in limiting TFH function intrinsically or by potentiating the suppressive capacity of TFR intrinsically, or due to the combination of the two. Generation of conditional knock-out mice, in which A2aR is specifically ablated in TFR independently, may help answer these questions. Additionally, there is the possibility of further role(s) for A2aR signaling directly on GC B cells, as we were able to detect functional A2aR expression on GC B cells (data not shown).

It is tempting to postulate that extracellular adenosine signaling through A2aR serves to limit T cell help within the GC to both regulate clonal entry into the GC, as T cell help has been shown to be limiting for this process (31), and maintain an appropriate level of T cell help within the GC to drive affinity maturation. This notion also raises the idea that limiting T cell help within the GC microenvironment by A2aR signaling on TFH and TFR may serve to limit the genetic event of class switch recombination, which is the product of induced DNA damage (32–34), and if left unchecked may lead to off-target deleterious mutations (35). Furthermore, this regulation of T cell help by A2aR may help prevent the generation of autoreactive effector B cells that occurs in uncontrolled GC responses such as in systemic lupus erythematous (36, 37).

In terms of vaccine design, it is important to appreciate that both A2aR agonist and A2aR antagonist have been safely administered in human trials and approved for human use (38–40), and A2aR signaling appears to be phylogenetically conserved on human CD4 T cells (19). Perhaps pharmacological manipulation of the A2a receptor during different time points following vaccination could modulate the magnitude and/or epitope specificity for responding B cells to difficult immunogens such as candidate flu and HIV vaccines. Moreover, it is also a possibility that stimulating A2aR during established GC reactions for certain immunogens may help guide affinity maturation, as excessive T cell help has been shown to impair this process (41).

Clearly, future studies are needed to answer these questions. We view this study as opening the door for future work to elucidate the full role of adenosine signaling in the vaccine response and in diseases in which GC-derived autoantibodies may contribute to the pathology.

Experimental Procedures

Mice and Immunizations

A2aR gene (Adora2a)-deficient mice were originally generated as described (42), and backcrossed on to C57Bl/6J for 13 generations. Mice were held under specific pathogen-free conditions at Northeastern University. Age- and sex-matched wild type C57Bl/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Female mice between 8 and 12 weeks of age were used for most experiments. TCRβ/δ knock-out mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and maintained as a breeding colony at Northeastern University. NP-OVA was conjugated in-house at a valency of 4–8 NP molecules per OVA. In most experiments, mice were immunized with 3 μg of NP-OVA i.p. in co-precipitated alum hydroxide. CGS21680 injections were given in Hanks' balanced salt solution subcutaneously twice daily at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg. All animal work was done in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocols at Northeastern University.

Cell Transfer

CD4+ Resting T cells were purified by magnetic depletion using the CD4 T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Depletion was done using an autoMACS (Miltenyi Biotec), and purity was assessed to be greater than 95% by flow cytometry following purification. Cells (ranging between 1 and 3 × 106/mice per experiment depending on recovery) were washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution and transferred i.p., and then recipient mice were rested for 4 days and immunized.

Cell Sorting and Flow Cytometry

Single cell suspensions were prepared by mechanical dissociation in FACS buffer (5% FCS in PBS). Cells were counted, and then Fc Block (2.4G2) was added for 10 min. Fluorescently conjugated mAbs were then added to each sample for 30 min at 4 °C. Fluorescently conjugated mAbs used were purchased from eBioscience, BD Biosciences, and BioLegend. Cells were acquired on a Cytek DxP 8 upgraded FACSCalibur, a BD Biosciences LSRII, or a BD Biosciences LSRFortessa. Cell sorting was done on a BD Biosciences Aria II. Analysis was done on FlowJo X (TreeStar). For cell sorting for T follicular and CD4 T cells, generally pools of 5–10 mice in a given experiment (day 8 following NP-OVA/alum) were used to recover enough cells for the functional assay to detect A2aR.

ELISA

cAMP detection was done essentially as described (18).

Histology

Spleens from immunized mice were frozen in Tissue-Tek compound in a liquid nitrogen-cooled bath of 2-methylbutane. 5-μm sections were cut on a cryostat, air-dried, fixed in a 1:1 mixture of acetone and methanol, and kept frozen until staining. The staining procedure was done generally as described (26).

For CD73 imaging, a Nikon Eclipse e80i was used with Spot software. Fluorochromes used were Alexa Fluor 350, FITC/anti-FITC Oregon Green 488, and phycoerythrin. For T cell quantification, images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 710 microscope, and then collected using Zen software. ImageJ/Fiji was used for analysis. Fluorochromes used include Alexa Fluor 488, phycoerythrin, and Pacific Blue. Mask files were created for GCs (B220+, GL-7+) and T cells (TCRβ+). T cell occupancy of GC was assessed by quantifying the percentage of the area of the GC mask that overlaps with the TCRβ mask.

Author Contributions

R. K. A. designed experiments, conceptual scope of the study, acquired and interpreted data, managed all aspects of the study, and wrote the manuscript. J. L. conducted experiments, performed histological imaging and analysis, and edited the manuscript. M. Silva conducted experiments and edited the manuscript. A. O. guided research and performed experiments. D. W. C. helped with experiments and edited the manuscript. M. T., P. P., S. S., and S. H. performed and helped with experiments. M. Sitkovsky offered the original idea, participated in interpretation of the results, and supervised the study and scope of research. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved final submission.

Acknowledgments

We thank both Dr. Ellis Reinherz and Dr. Garnett Kelsoe for long term support, helpful discussions, and guidance. We thank Maris Handley for expert cell sorting and Dr. Erin Cram for generous use of the Cram lab microscope.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants U19 AI 091693 and R01 CA 111985 (to M. Sitkovsky). The authors R. K. A., S. H., and M. Sitkovsky have filed a patent partially based on this work. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- NP-OVA

- 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl(acetyl) ovalbumin

- alum

- aluminum hydroxide

- A2aR

- A2a adenosine receptor

- A2aRKO

- A2a adenosine receptor knockout

- GC

- germinal center

- TFH

- T follicular helper cell(s)

- TFR

- T follicular regulatory cell(s)

- Treg

- T regulatory cell(s)

- CGS

- exAdo

- extracellular adenosine

- CTLA-4

- cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

- TCR

- T cell receptor.

References

- 1. Victora G. D., and Nussenzweig M. C. (2012) Germinal centers. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 30, 429–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crotty S. (2014) T follicular helper cell differentiation, function, and roles in disease. Immunity 41, 529–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crotty S. (2011) Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH). Annu. Rev. Immunol. 29, 621–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vinuesa C. G., Linterman M. A., Yu D., and MacLennan I. C. (2016) Follicular helper T cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 34, 335–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Muppidi J. R., Lu E., and Cyster J. G. (2015) The G protein-coupled receptor P2RY8 and follicular dendritic cells promote germinal center confinement of B cells, whereas S1PR3 can contribute to their dissemination. J. Exp. Med. 212, 2213–2222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moriyama S., Takahashi N., Green J. A., Hori S., Kubo M., Cyster J. G., and Okada T. (2014) Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 is critical for follicular helper T cell retention in germinal centers. J. Exp. Med. 211, 1297–1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Green J. A., Suzuki K., Cho B., Willison L. D., Palmer D., Allen C. D., Schmidt T. H., Xu Y., Proia R. L., Coughlin S. R., and Cyster J. G. (2011) The sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor S1P2 maintains the homeostasis of germinal center B cells and promotes niche confinement. Nat. Immunol. 12, 672–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li J., Lu E., Yi T., and Cyster J. G. (2016) EBI2 augments Tfh cell fate by promoting interaction with IL-2-quenching dendritic cells. Nature 533, 110–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lappano R., and Maggiolini M. (2011) G protein-coupled receptors: novel targets for drug discovery in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 47–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eisen H. N. (2014) Affinity enhancement of antibodies: how low-affinity antibodies produced early in immune responses are followed by high-affinity antibodies later and in memory B-cell responses. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2, 381–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crotty S. (2015) A brief history of T cell help to B cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 185–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Linterman M. A., Pierson W., Lee S. K., Kallies A., Kawamoto S., Rayner T. F., Srivastava M., Divekar D. P., Beaton L., Hogan J. J., Fagarasan S., Liston A., Smith K. G., and Vinuesa C. G. (2011) Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nat. Med. 17, 975–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chung Y., Tanaka S., Chu F., Nurieva R. I., Martinez G. J., Rawal S., Wang Y. H., Lim H., Reynolds J. M., Zhou X. H., Fan H. M., Liu Z. M., Neelapu S. S., and Dong C. (2011) Follicular regulatory T cells expressing Foxp3 and Bcl-6 suppress germinal center reactions. Nat. Med. 17, 983–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sage P. T., Paterson A. M., Lovitch S. B., and Sharpe A. H. (2014) The coinhibitory receptor CTLA-4 controls B cell responses by modulating T follicular helper, T follicular regulatory, and T regulatory cells. Immunity 41, 1026–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wing J. B., Ise W., Kurosaki T., and Sakaguchi S. (2014) Regulatory T cells control antigen-specific expansion of Tfh cell number and humoral immune responses via the coreceptor CTLA-4. Immunity 41, 1013–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ohta A., and Sitkovsky M. (2001) Role of G-protein-coupled adenosine receptors in downregulation of inflammation and protection from tissue damage. Nature 414, 916–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eltzschig H. K., Sitkovsky M. V., and Robson S. C. (2012) Purinergic signaling during inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 2322–2333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ohta A., Gorelik E., Prasad S. J., Ronchese F., Lukashev D., Wong M. K., Huang X., Caldwell S., Liu K., Smith P., Chen J. F., Jackson E. K., Apasov S., Abrams S., and Sitkovsky M. (2006) A2A adenosine receptor protects tumors from antitumor T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13132–13137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koshiba M., Rosin D. L., Hayashi N., Linden J., and Sitkovsky M. V. (1999) Patterns of A2A extracellular adenosine receptor expression in different functional subsets of human peripheral T cells. Flow cytometry studies with anti-A2A receptor monoclonal antibodies. Mol. Pharmacol. 55, 614–624 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hynes T. R., Yost E. A., Yost S. M., Hartle C. M., Ott B. J., and Berlot C. H. (2015) Inhibition of Gαs/cAMP signaling decreases TCR-stimulated IL-2 transcription in CD4+ T helper cells. J. Mol. Signal. 10, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu S., Shao Q. Q., Sun J. T., Yang N., Xie Q., Wang D. H., Huang Q. B., Huang B., Wang X. Y., Li X. G., and Qu X. (2013) Synergy between the ectoenzymes CD39 and CD73 contributes to adenosinergic immunosuppression in human malignant gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 15, 1160–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abbott R. K., Thayer M., Labuda J., Silva M., Philbrook P., Cain D. W., Kojima H., Hatfield S., Sethumadhavan S., Ohta A., Reinherz E. L., Kelsoe G., and Sitkovsky M. (2016) Germinal center hypoxia potentiates immunoglobulin class switch recombination. J. Immunol. 197, 4014–4020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hart M. L., Grenz A., Gorzolla I. C., Schittenhelm J., Dalton J. H., and Eltzschig H. K. (2011) Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α-dependent protection from intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury involves ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) and the A2B adenosine receptor. J. Immunol. 186, 4367–4374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24. Bullen J. W., Tchernyshyov I., Holewinski R. J., DeVine L., Wu F., Venkatraman V., Kass D. L., Cole R. N., Van Eyk J., and Semenza G. L. (2016) Protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation stimulates the transcriptional activity of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Sci. Signal. 9, ra56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Synnestvedt K., Furuta G. T., Comerford K. M., Louis N., Karhausen J., Eltzschig H. K., Hansen K. R., Thompson L. F., and Colgan S. P. (2002) Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates permeability changes in intestinal epithelia. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 993–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hatfield S. M., Kjaergaard J., Lukashev D., Schreiber T. H., Belikoff B., Abbott R., Sethumadhavan S., Philbrook P., Ko K., Cannici R., Thayer M., Rodig S., Kutok J. L., Jackson E. K., Karger B., et al. (2015) Immunological mechanisms of the antitumor effects of supplemental oxygenation. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 277ra30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hatfield S. M., Kjaergaard J., Lukashev D., Belikoff B., Schreiber T. H., Sethumadhavan S., Abbott R., Philbrook P., Thayer M., Shujia D., Rodig S., Kutok J. L., Ren J., Ohta A., Podack E. R., et al. (2014) Systemic oxygenation weakens the hypoxia and hypoxia inducible factor 1α-dependent and extracellular adenosine-mediated tumor protection. J. Mol. Med. 92, 1283–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Iyer S. S., Latner D. R., Zilliox M. J., McCausland M., Akondy R. S., Penaloza-Macmaster P., Hale J. S., Ye L., Mohammed A. U., Yamaguchi T., Sakaguchi S., Amara R. R., and Ahmed R. (2013) Identification of novel markers for mouse CD4+ T follicular helper cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 3219–3232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Choi Y. S., Kageyama R., Eto D., Escobar T. C., Johnston R. J., Monticelli L., Lao C., and Crotty S. (2011) ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity 34, 932–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ohta A., and Sitkovsky M. (2014) Extracellular adenosine-mediated modulation of regulatory T cells. Front. Immunol. 5, 304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schwickert T. A., Victora G. D., Fooksman D. R., Kamphorst A. O., Mugnier M. R., Gitlin A. D., Dustin M. L., and Nussenzweig M. C. (2011) A dynamic T cell-limited checkpoint regulates affinity-dependent B cell entry into the germinal center. J. Exp. Med. 208, 1243–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Revy P., Muto T., Levy Y., Geissmann F., Plebani A., Sanal O., Catalan N., Forveille M., Dufourcq-Labelouse R., Gennery A., Tezcan I., Ersoy F., Kayserili H., Ugazio A. G., et al. (2000) Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) deficiency causes the autosomal recessive form of the Hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM2). Cell 102, 565–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Muramatsu M., Kinoshita K., Fagarasan S., Yamada S., Shinkai Y., and Honjo T. (2000) Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell 102, 553–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Muramatsu M., Sankaranand V. S., Anant S., Sugai M., Kinoshita K., Davidson N. O., and Honjo T. (1999) Specific expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a novel member of the RNA-editing deaminase family in germinal center B cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 18470–18476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shaffer A. L. 3rd, Young R. M., and Staudt L. M. (2012) Pathogenesis of human B cell lymphomas. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 30, 565–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Choi J. Y., Ho J. H., Pasoto S. G., Bunin V., Kim S. T., Carrasco S., Borba E. F., Gonçalves C. R., Costa P. R., Kallas E. G., Bonfa E., and Craft J. (2015) Circulating follicular helper-like T cells in systemic lupus erythematosus: association with disease activity. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 988–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ueno H., Banchereau J., and Vinuesa C. G. (2015) Pathophysiology of T follicular helper cells in humans and mice. Nat. Immunol. 16, 142–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Navarro G., Borroto-Escuela D. O., Fuxe K., and Franco R. (2016) Purinergic signaling in Parkinson's disease: relevance for treatment. Neuropharmacology 104, 161–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thompson C. A. (2008) FDA approves pharmacologic stress agent. Am. J. Health Syst Pharm. 65, 890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Iskandrian A. E., Bateman T. M., Belardinelli L., Blackburn B., Cerqueira M. D., Hendel R. C., Lieu H., Mahmarian J. J., Olmsted A., Underwood S. R., Vitola J., Wang W., and ADVANCE MPI Investigators (2007) Adenosine versus regadenoson comparative evaluation in myocardial perfusion imaging: results of the ADVANCE phase 3 multicenter international trial. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 14, 645–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Preite S., Baumjohann D., Foglierini M., Basso C., Ronchi F., Fernandez Rodriguez B. M., Corti D., Lanzavecchia A., and Sallusto F. (2015) Somatic mutations and affinity maturation are impaired by excessive numbers of T follicular helper cells and restored by Treg cells or memory T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 45, 3010–3021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ledent C., Vaugeois J. M., Schiffmann S. N., Pedrazzini T., El Yacoubi M., Vanderhaeghen J. J., Costentin J., Heath J. K., Vassart G., and Parmentier M. (1997) Aggressiveness, hypoalgesia and high blood pressure in mice lacking the adenosine A2a receptor. Nature 388, 674–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]