Abstract

Identification of patient characteristics influencing treatment outcomes is a top low back pain (LBP) research priority. Results from the STarT Back Trial support the effectiveness of prognostic stratified care for LBP compared to current best care, however patient characteristics associated with treatment response have not yet been explored. The purpose of this secondary analysis was to identify treatment-effect modifiers within the STarT Back Trial at 4 months follow-up (n=688). Treatment response was dichotomized using back-specific physical disability measured by the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (≥7). Candidate modifiers were identified using previous literature and evaluated using logistic regression with statistical interaction terms to provide preliminary evidence of treatment-effect modification. Socioeconomic status (SES) was identified as an effect modifier for disability outcomes (OR = 1.71, P=.028). High SES patients receiving prognostic stratified care were 2.5 times less likely to have a poor outcome compared to low SES patients receiving best current care (OR = 0.40, P=.006). Education level (OR = 1.33, P=.109) and number of pain medications (OR = 0.64, P=.140) met our criteria for effect modification with weaker evidence (0.20>P≥0.05). These findings provide preliminary evidence for SES, education, and number of pain medications as treatment-effect modifiers of prognostic stratified care delivered in the STarT Back Trial.

Perspective

This analysis provides preliminary exploratory findings about the characteristics of patients who might least likely benefit from targeted treatment using prognostic stratified care for low back pain.

Keywords: low back pain, socioeconomic status, treatment effect modification, stratified care, subgrouping

Background

Identification of patients that are most likely to positively respond or gain the greatest benefit from different treatment approaches has been indicated as a top low back pain (LBP) research priority.15, 18, 60 The STarT Back trial36 evaluated the clinical and cost effectiveness of stratified primary care that involved targeting treatment to subgroups based on their prognostic risk of persistent disabling pain.36 The trial results were favorable for the overall comparison between stratified care compared to current best practice at both 4 and 12 month follow-ups and for the comparison between patients at low, medium and high risk of persistent pain in each arm of the trial.36 In this paper, we focus on identifying the characteristics of patients who benefitted the most (and least) from this stratified care approach.

Identifying which patient level variables influence treatment outcomes has the potential to enhance clinical reasoning.30 Methodological recommendations for study design, analysis and interpretation of such subgroup analyses are available including the need for clear terminology.7, 41, 59, 65, 69 In this study we attempt to distinguish between variables that demonstrated treatment effect modification for stratified care outcomes from those that were predictive of patient outcomes regardless of treatment. We use treatment effect modifiers are used for variables measured at baseline that demonstrated an interaction with the stratified care treatment outcomes (ie. in whom treatment was least effective).44, 59 For example, other study findings suggest older age as a potential treatment effect modifier for chronic LBP patients receiving Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (ie, McKenzie method) compared to Back School, indicating age may be an important factor to consider when identifying responders to this specific treatment.24 We use prognostic factors for variables measured at baseline that were predictive of patient outcomes but did not interact with allocated treatment and were therefore not providing information specific to the stratified care intervention response.44, 59 For example, psychological factors have been found to be strong prognostic indicators for LBP outcomes, however not consistently predictive of response to physical therapist-led exercise and/or advice (ie, a specific treatment).68

Most clinical trials are not adequately powered to investigate subgroup effects, however such analyses can still provide important hypothesis-generating information for future research.44, 59 Pincus et al.59 recommend four key criteria for treatment effect modification analysis using clinical trial data: 1) potential modifiers should be measured prior to randomization; 2) selection of potential modifiers should be based on theory or evidence; 3) measurement of baseline factors should be reliable and valid; and 4) an explicit test of the interaction between potential modifiers and treatment is required. Gurung et al.28 recently used these criteria in their systematic review of potential LBP treatment effect modifiers from four clinical trials, testing acupuncture,12, 78 exercise and manual therapy,71 and psychological treatment.46 Variables associated with treatment outcome that had strong evidence included patients’ age, employment status and type, back pain severity, narcotic medication use, treatment expectations and education level. Variables associated with treatment outcome that had weak evidence included gender, psychological distress, initial pain intensity, disability, and quality of life.

STarT Back trial36 patient characteristics that interact with treatment outcome have not yet been evaluated and these have the potential to provide additional information about which patients might be less likely to benefit from matched treatment in this stratified care approach. Therefore, the purpose of this analysis was to explore potential patient level treatment effect modifiers at four months follow-up. Specifically, our strategy was twofold consisting of: 1) identification of potential treatment effect modification using descriptive statistics to explore the patient characteristics associated with treatment outcome in which there was no benefit from stratified care and 2) preliminary confirmation of treatment effect modification using formal moderation analysis with a test for statistical interaction.

Methods

STarT Back Trial

We conducted a secondary analysis of data from the STarT Back trial.36 Briefly, the STarT Back trial was a parallel, two-armed, randomized controlled trial that evaluated the clinical and cost effectiveness of prognostic risk stratified primary care (intervention) with non-stratified current best care (control) for LBP patients with follow-up at 4 and 12 months. Participants were recruited from 10 general practices in the North West Midlands region of England, UK.

STarT Back Trial Procedures

All participants received an initial 30-minute physical therapy evaluation that was supplemented with a brief intervention consisting of LBP education and advice. Subsequent interventions were based on participant randomized allocation. Additional treatment for control group participants was at the discretion of the treating physical therapist, as per current best care. Additional treatment for intervention group participants was based on baseline risk stratification (low, medium, or high risk for persistent LBP disability) determined using the STarT Back tool.34 Details of the matched treatments have previously been described elsewhere.31

Description of Candidate Treatment Effect Modifiers

Baseline factors were collected from each participant prior to randomization and treatment allocation. Selection of potential treatment effect modifiers for this secondary analysis was based on their influential relationship with LBP clinical outcome as indicated by previous literature (defined below). For this analysis we focused only on treatment modifiers that would not be expected to change during treatment and therefore could be used to characterize patients. Other factors such as pain intensity or psychological variables that were specifically targeted through stratified care interventions and therefore expected to change were not included based on a priori determination. The selected treatment effect modifiers are described below with the hypothesized direction of influence defined for each factor.

Age was categorized into one of three groups (≤ 44; 45–64; ≥65 years) similar to previous studies.62 We hypothesized that prognostic stratified care would be less effective compared to best current care for older (≥65 years) compared to younger patients.28, 32, 46, 63, 66, 76

Gender was categorized into one of two groups (female or male). We hypothesized that prognostic stratified care would be less effective compared to best current care for females compared to males after controlling for baseline disability based on findings from previous review studies.3, 21

Education level was categorized into one of four groups (further or higher education, other work or non-work related, compulsory education, or no qualifications).57 Further education includes all non-advanced courses taken after the period of compulsory education including secondary school, whereas higher education is beyond secondary school commonly offered at the university level. Other work or non-work related education includes other types of non-school, non-university education and training. Compulsory education is required for all children between 5 and 16 years of age. We hypothesized that prognostic stratified care would be less effective compared to current best care for patients with lower levels of education.8, 16, 28, 46

Socioeconomic status (SES) was assessed using the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC) reduced method which is primarily based on job occupation.56 Categorization was solely based on job occupation. The NS-SEC was collapsed into one of three classes of SES (Upper [higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations]; Middle [intermediate occupations]; and Lower [lower supervisory and technical occupations, semi-routine and routine occupations]). We hypothesized that prognostic stratified care would be less effective compared to current best care for patients with lower SES.8–10, 52

Current employment status was dichotomized (yes or no). We hypothesized that prognostic stratified care would be less effective compared to current best care for patients that were not currently employed.27, 28, 46, 52, 76

Work satisfaction was dichotomized (satisfied or not satisfied) based on responses to a five-point Likert scale. ‘Very satisfied’ and ‘satisfied’ responses were collapsed to create a ‘satisfied’ variable and ‘no opinion’, ‘not very satisfied’, and ‘not at all satisfied’ responses were collapsed to create a ‘not satisfied’ variable. We hypothesized that prognostic stratified care would be less effective compared to current best care for patients that were not satisfied with their work.14, 47, 50

Duration of current symptoms was categorized into one of three groups (<1 month; 1 to 3 months; or >3 months). We hypothesized that prognostic stratified care would be less effective compared to current best care for patients that reported a longer duration of symptoms.33, 63, 66, 76

Number of current pain medications was categorized into one of three groups (0; 1 to 2; ≥3). We hypothesized that prognostic stratified care would be less effective compared to current best care for patients that reported using three or more pain medications.23, 25, 26, 38, 51, 61

Expectations for recovery at four months was categorized into one of three groups (high, moderate, low) based on tertile cutoff scores from an 11-point scale with ‘0’ indicating ‘completely better’ to ‘10’ indicating ‘extreme pain’. We hypothesized that prognostic stratified care would be less effective compared to best current care for patients reporting lower expectations for recovery.4, 8, 22, 28, 33, 54

Definition of Outcome

We defined outcome as LBP related physical disability at four months following randomization assessed using the Roland and Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ).64 The 24-item RMDQ assesses physical function over the past 24 hours and has a potential scoring range of 0 ‘no disability due to LBP’ to 24 ‘maximum disability due to LBP’, with higher scores indicating higher LBP related disability. The RMDQ has been found to have high levels of test-retest reliability, internal consistency, validity, and responsiveness.11 To be consistent with previous research involving the STarT Back screening tool34, 77 disability outcome scores at four months were recoded into Satisfactory Outcome (RMDQ <7) and Poor Outcome (RMDQ ≥7). Our rationale for analyzing LBP related disability outcomes at 4 months was based on detection of larger between group effect sizes in the STarT Back trial at this time-point,36 therefore identification of treatment effect modifiers was more likely at 4 months compared to 12 months.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York). Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate for treatment effect modification within and between baseline factors and treatment allocation (ie, stratified care versus best current care) for disability outcome. Chi-square testing was used to compare the proportion of patients with poor outcome (RMDQ ≥7) across treatment groups at each level of individual baseline factors to provide an indication of potential treatment effect modification from stratified care. Specifically, we were interested in potential modifiers associated with a greater proportion of patients with poor outcome for the stratified care group compared to best current care (P<.05), which would potentially provide an indication of treatment effect modification.

Once potential treatment effect modifiers were identified from the above descriptive analysis, they were confirmed with a formal moderation analysis using a test for statistical interaction.59, 69 We fully acknowledge that our sample size may not be adequately powered for these statistical interaction tests following guidance on minimal group size,59 therefore the results should only be interpreted as preliminary. Separate binary logistic regression models were used to evaluate contributions of each individual baseline potential treatment effect modifier and treatment group allocation. We tested for treatment modification by incorporating a group x factor interaction term. Specifically, each model was built using three separate blocks: 1) baseline RMDQ score and treatment group; 2) baseline factor; 3) treatment group x baseline factor interaction term. All interactions with a p-value ≤0.20 were reported to ensure all possible treatment effect modifiers were identified and categorized into exploratory (P<0.05) or additional exploratory evidence (0.20>P≥0.05) similar to criteria used for a recent systematic review.28

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of STarT Back trial participants (n = 851).

| Variable | Total Sample | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| ≤44 | 329 (38.7%) | 221 (38.9%) | 108 (38.2%) |

| 45–64 | 374 (43.9%) | 240 (42.3%) | 134 (47.3%) |

| ≥65 | 148 (17.4%) | 107 (18.8%) | 41 (14.5%) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 500 (58.8%) | 330 (58.1%) | 170 (60.1%) |

| Male | 351 (41.2%) | 238 (41.9%) | 113 (39.9%) |

| Education | |||

| Further or higher education | 230 (27.1%) | 156 (27.5%) | 74 (26.2%) |

| Other work or non-work related | 280 (32.9%) | 185 (32.6%) | 95 (33.7%) |

| Compulsory education | 164 (19.3%) | 104 (18.3%) | 60 (21.3%) |

| No qualifications | 176 (20.7%) | 123 (21.7%) | 53 (18.8%) |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Upper | 233 (28.6%) | 162 (29.9%) | 71 (26.0%) |

| Middle | 209 (25.6%) | 132 (24.4%) | 77 (28.2%) |

| Lower | 373 (45.8%) | 248 (45.8%) | 125 (45.8%) |

| Currently employed | |||

| Yes | 524 (61.6%) | 350 (61.6%) | 174 (61.5%) |

| No | 327 (38.4%) | 218 (38.4%) | 109 (38.5%) |

| Work satisfaction* | |||

| Satisfied | 427 (81.5%) | 288 (82.3%) | 139 (79.9%) |

| Not satisfied | 97 (18.5%) | 62 (17.7%) | 35 (20.1%) |

| Duration of symptoms (How long since whole month without pain?) | |||

| < 1 month | 151 (17.7%) | 97 (17.1%) | 54 (19.1%) |

| 1–3 months | 190 (22.3%) | 124 (21.8%) | 66 (23.3%) |

| > 3 months | 510 (59.9%) | 347 (61.1%) | 163 (57.6%) |

| Pain medications | |||

| 0 | 223 (26.2%) | 136 (23.9%) | 87 (30.7%) |

| 1 to 2 | 444 (52.2%) | 289 (50.9%) | 155 (54.8%) |

| ≥3 | 184 (21.6%) | 143 (25.2%) | 41 (14.5%) |

| Expectation for recovery at 4-months | |||

| High | 342 (40.4%) | 222 (39.2%) | 120 (42.7%) |

| Moderate | 384 (45.3%) | 261 (46.1%) | 133 (43.8%) |

| Low | 121 (14.3%) | 83 (14.7%) | 38 (13.5%) |

Work satisfaction estimates based on participants that were currently employed (n=524).

Potential Treatment Effect Modifiers

The results from the descriptive analysis demonstrated, as expected, that there were similar and consistent within treatment arm relationships between several baseline potential treatment effect modifiers and the proportion of patients with poor outcome. General prognostic factors with an increased proportion of patients with a poor outcome in both stratified care and best current care groups included; older age, lower level of education, greater number of pain medications, and lower expectations for recovery (Table 2). Inspection of the between treatment arm comparisons generally and consistently revealed a higher proportion of best current care patients associated with poor outcome (in favor of stratified care), however there were several baseline factors where the proportion of stratified care patients associated with poor outcome was similar between treatment arms (P >.05) indicating stratified care did not benefit and signifying potential treatment effect modification (ie, lower education, low SES, lack of current employment, >=3 pain medications, and low expectations for recovery) (Table 2). Each factor associated with non-significant (P > .05) between treatment arm relationships was selected for subsequent formal moderation analysis to test for statistical interactions using logistic regression.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants with poor treatment outcome (RMDQ ≥7) at 4 months.

| Variable | Treatment Allocation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||

| Age | |||

| ≤44 | 32 (20.1%) | 22 (33.3%) | P = .052 |

| 45–64 | 70 (33.2%) | 46 (39.7%) | P = .292 |

| ≥65 | 35 (36.5%) | 17 (42.5%) | P = .644 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 85 (31.0%) | 53 (39.3%) | P = .119 |

| Male | 52 (27.1%) | 32 (36.8%) | P = .134 |

| Education | |||

| Further or higher education | 23 (19.0%) | 18 (30.0%) | P = .140 |

| Other work or non-work related | 35 (22.3%) | 28 (37.8%) | P = .021 |

| Compulsory education | 26 (32.1%) | 19 (43.2%) | P = .298 |

| No qualifications | 53 (49.5%) | 19 (44.2%) | P = .684 |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Upper | 26 (19.3%) | 21 (38.9%) | P = .009 |

| Middle | 30 (27.5%) | 24 (35.8%) | P = .322 |

| Lower | 70 (35.4%) | 35 (37.2%) | P = .866 |

| Currently employed | |||

| Yes | 57 (20.6%) | 44 (32.8%) | P = .010 |

| No | 80 (42.3%) | 41 (46.6%) | P = .588 |

| Work satisfaction | |||

| Satisfied | 48 (20.9%) | 33 (30.8%) | P = .065 |

| Not satisfied | 9 (19.1%) | 11 (40.7%) | P = .081 |

| Duration of symptoms (How long since whole month without pain?) | |||

| < 1 month | 23 (28.4%) | 16 (40.0%) | P = .281 |

| 1–3 months | 13 (12.9%) | 13 (23.2%) | P = .150 |

| > 3 months | 101 (35.6%) | 56 (44.4%) | P = .114 |

| Pain medications | |||

| 0 | 18 (17.1%) | 13 (18.3%) | P = .997 |

| 1 to 2 | 77 (31.2%) | 54 (46.6%) | P = .006 |

| ≥3 | 42 (36.8%) | 18 (51.4%) | P = .179 |

| Expectation for recovery at 4-months | |||

| High | 32 (16.9%) | 26 (28.9%) | P = .031 |

| Moderate | 67 (31.9%) | 36 (36.7%) | P = .483 |

| Low | 36 (55.4%) | 23 (71.9%) | P = .179 |

RMDQ – Roland and Morris Disability Questionnaire.

% indicates – percent of those that had poor treatment outcome (RMDQ≥7).

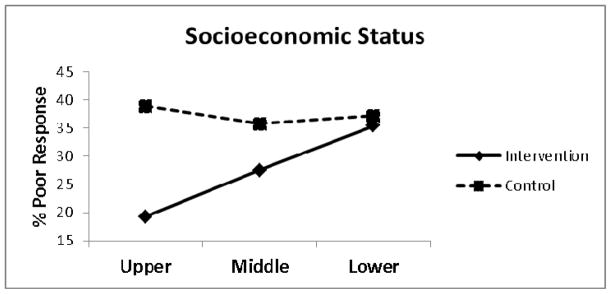

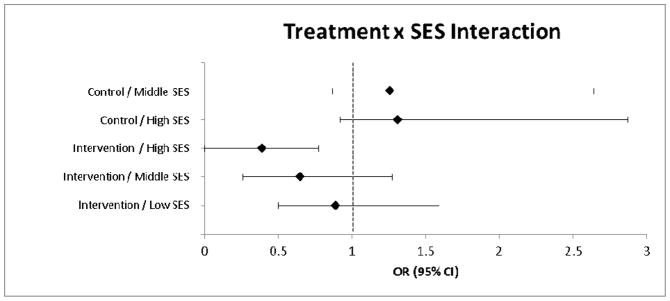

Exploratory Evidence for Treatment Effect Modification

The results of the logistic regression are provided in Table 3. Socioeconomic status (SES) was identified as the only treatment effect modifier for poor treatment outcome (RMDQ ≥7) at four months (OR = 1.71, 95% CI: 1.06, 2.77, P = .028) (Figure 1). Decomposition of the treatment x SES interaction term indicated that compared to those receiving best current care with low SES, those receiving stratified care with high SES were 2.5 times less likely to have a poor treatment outcome (OR = 0.40, 95% CI: 0.20, 0.77, P = .006) (Figure 2). Further exploratory descriptive analysis indicated a greater proportion of low SES patients with poor treatment outcome that received stratified care compared to best current care for low (13.0% and 9.5%) and medium (33.7% and 25.0%) risk subgroups, however this was not observed for the high risk subgroup (55.0% and 69.7%) and needs to be interpreted with caution as cell counts were very low. Similar trends were also observed for patients with low education (ie, no qualifications) for low (18.8% and 11.1%), medium (37.0% and 36.8%) and high (73.3% and 71.3%) risk subgroups. There were no other STarT Back risk groups for whom stratified care produced worse treatment outcomes than those receiving current best care.

Table 3.

Results of separate logistic regression models for 4 month RMDQ (≥7) poor outcome.

| Factor | Treatment Allocation | Factor x Group Term | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.14 (0.72, 1.80), P=.567 | 0.46 (0.15, 1.41), P=.173 | 1.12 (0.65, 1.95), P=.682 |

| Gender | 0.94 (0.50, 1.77), P=.846 | 0.62 (0.19, 1.96), P=.414 | 0.95 (0.43, 2.07), P=.890 |

| Education | 1.09 (0.82, 1.45), P=.558 | 0.28 (0.11, 0.71), P=.008 | 1.33 (0.94, 1.90), P=.109 |

| Socioeconomic status | 0.87 (0.59, 1.28), P=.474 | 0.18 (0.06, 0.54), P=.003 | 1.71 (1.06, 2.77), P=.028 |

| Employment | 1.63 (0.87, 3.06), P=.128 | 0.44 (0.13, 1.42), P=.169 | 1.18 (0.54, 2.57), P=.676 |

| Current status | 1.31 (0.59, 2.91), P=.515 | 0.57 (0.12, 2.59), P=.465 | 0.96 (0.35, 2.66), P=.934 |

| Work satisfaction | 1.37 (0.53, 3.53), P=.513 | 0.83 (0.17, 4.09), P=.822 | 0.68 (0.19, 2.42), P=.554 |

| Symptom duration | 1.58 (1.05, 2.39), P=.029 | 0.60 (0.16, 2.22), P=.443 | 0.96 (0.58, 1.60), P=.889 |

| Medication | 1.60 (0.97, 2.62), P=.063 | 1.36 (0.39, 4.72), P=.634 | 0.64 (0.35, 1.16), P=.140 |

| Expectation | 1.70 (1.07, 2.69), P=.025 | 0.35 (0.12, 1.05), P=.062 | 1.28 (0.72, 2.25), P=.403 |

Values are odds ratio (95% confidence intervals) and associated P value for the effect of the factor, the main effect of treatment group, and the interaction between factor and treatment group on 4 month RMDQ (≥7) poor outcome status. Binary logistic final model estimates (baseline RMDQ included in all models). Treatment allocation (reference = control group)

Figure 1.

Poor treatment response by socioeconomic status

Figure 2.

Decomposed treatment response by socioeconomic status interactions.

Reference: Control /Low SES

SES = socioeconomic status; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

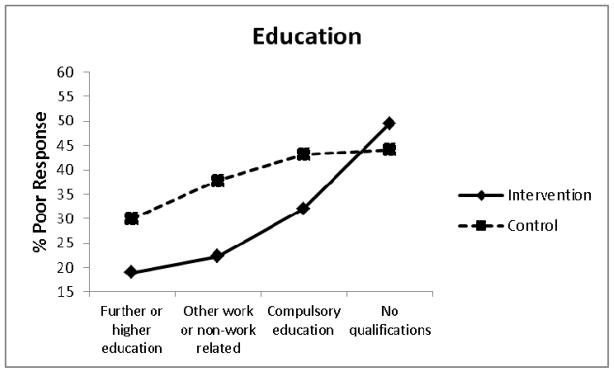

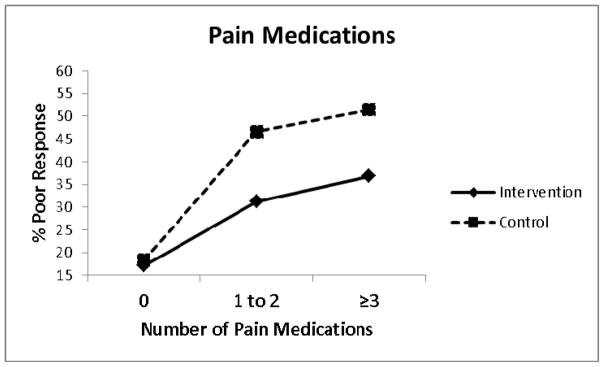

Additional Exploratory Evidence for Treatment Effect Modification

Other treatment effect modifiers meeting our criteria for treatment effect modification with additional exploratory evidence (0.20>P≥0.05) included education level (OR = 1.33, 95% CI: 0.94, 1.90, P = .109) (Figure 3) and number of current pain medications (OR = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.35, 1.16, P = .140) (Figure 4). Decomposition of the treatment x education interaction term indicated that compared to those receiving best current care with ‘no qualifications’, those receiving stratified care who had ‘further or higher education’ were approximately 3 times less likely to have a poor treatment outcome (OR = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.14, 0.63, P = .002). Decomposition of the treatment x pain medication interaction term indicated that compared to those receiving best current care who were using ‘≥3 pain medications’, those receiving stratified care and using ‘no pain medications’ were approximately 5 times less likely to have a poor treatment outcome (OR = 0.19, 95% CI: 0.08, 0.45, P < .001).

Figure 3.

Poor treatment response by level of education.

Figure 4.

Poor treatment response by number of pain medications.

Comparative Moderation Analysis Findings

Additional support for treatment effect modification was reduced when performing similar moderation analyses using linear regression with either RMDQ percent change or continuous scale scores at four months serving as the dependent variable in separate models (complete data not provided). Specifically, observed treatment x SES statistical interaction p-values changed from 0.028 (RMDQ ≥7 model) to 0.066 (RMDQ percent change score model) and 0.072 (RMDQ continuous scale score model).

Discussion

Statement of Principal Findings

The aim of this secondary analysis was to explore for baseline patient level treatment effect modifiers for stratified care within the STarT Back trial, with a focus on those that were associated with a poor treatment outcome. We found that stratified care was associated with fewer patients of high SES with poor outcome (19.3%) compared to best current care (38.9%). However, in patients categorized as low SES the proportion with poor outcome was similar (35.4% and 37.2%). Treatment effect modification was statistically significant (P = .028) for SES and decomposition of the interaction indicated that compared to those receiving best current care who were classed as low SES, those receiving stratified care classed as high SES were 2.5 times less likely to have a poor treatment outcome. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have reported treatment effect modification by SES for other health conditions.48 Weaker evidence for treatment effect modification was found for education and number of pain medications, which although consistent with previous findings, require further exploration in adequately powered studies.

Socioeconomic Status

The observation in this exploratory analysis that the proportion of low SES patients with poor outcome was very similar in both treatment arms of the trial (35.4% and 37.2%) is of potential clinical importance. Although we were not able to definitively determine if stratified care was more beneficial for high SES participants or less beneficial for low SES participants, two plausible theories may provide explanation of the potential influence of SES. First, lower SES patients did not beneficially respond to stratified care (ie, the matched treatments were not sufficiently tailored for lower SES patients, particularly it would seem from descriptive data only, in the STarT Back Tool’s low and medium risk subgroups). Previous suggestions have indicated that increased patient commitment, motivation and potentially more intensive treatment may be required for patients at high risk with other health conditions.45 It is also plausible that barriers to good health outcomes commonly encountered by low SES patients (eg. low health literacy, poorer access to care) involve complex interactions at both the environmental and individual level and these may have influenced our results.9 Therefore, modifying treatment approaches to meet the needs of different SES groups has been previously suggested74 which may have implications for all patients regardless of risk status for clinical outcomes. Second, there is the potential that low SES patients enrolled in the STarT Back trial36 shared similar characteristics to patients that do not respond to LBP treatments in general. For example, secondary analysis of data (n = 949) from the UKBEAM trial where participants were randomized to receive either 1) best general practice care only or in addition: 2) spinal manipulation, 3) exercise or 4) combined spinal manipulation and exercise; found similar findings to our study with the intervention showing a less favorable treatment effect for certain individuals based on three SES indicators.52 Specifically, study participants from areas of high deprivation, with less education, and who were not working consistently (ie. those with low SES) reported greater LBP related disability across all treatment groups.52

Socioeconomic disparities are associated with health inequalities for a variety of conditions including musculoskeletal disorders.53, 55 However, SES influence on LBP outcomes has not been extensively evaluated,10, 73 particularly in comparison to other health conditions. For example, those with higher SES have consistently achieved greater rates of long term abstinence compared to those with lower SES following participation in tobacco dependence treatment programs.67, 75 Therefore, it is not surprising that alternative or enhanced treatments have been suggested for health conditions19, 39, 74 including LBP 9, 17 that specifically consider the circumstances of patients with low SES. Previous suggestions have also indicated that self-management approaches, particularly those incorporating cognitive behavioral principles, may be more appropriate for higher SES individuals.9, 10, 17 Consequently, identifying and addressing barriers that low SES patients commonly encounter such as low health knowledge or literacy 6, 13, 70, 72 is appealing as it has potential to enhance LBP treatment outcomes for this often underserved patient population.

Additional Exploratory Evidence for Treatment Effect Modification

Treatment effect modification trends were also observed for education and use of pain medication, findings similar to a recent systematic review that identified potential moderators for response to LBP treatment.28 Gurung, et al.28 identified younger age, being employed or in sedentary occupations, less narcotic medication use, higher levels of education, and greater positive treatment expectations as potential treatment effect modifiers for positive LBP treatment response using data generated from four randomized trials. In addition, prognostic capabilities associated with lower education level8, 16, 76 and using an increased number of pain medications23, 51 have been reported for musculoskeletal pain clinical outcomes in previous studies that have not specifically tested for treatment effect modification. Collectively, our findings support the need for further exploration of treatment effect modification through adequately powered studies and these should include patient level factors such as education level and use of pain medications.

Although we were not able to identify other treatment effect modifiers based on statistical interactions, several factors demonstrated prognostic capabilities for both intervention and control group outcomes. These findings can inform future LBP intervention studies by providing hypothesis generating information and highlight the fundamental nature of prognostic research from identifying priority areas for risk stratification to evaluating potential candidate factors that may predict treatment response.37 For example, older age was associated with an increased proportion of patients with poor outcome compared to younger age, which is consistent with previous LBP prognostic study findings.32, 33, 63, 76 Moreover, patients with lower expectations for recovery were more likely to have a poor outcome compared to those with higher expectations, and this is also consistent with previous LBP prognostic study findings.8, 29, 42

Strengths and Weaknesses

We conducted secondary analyses of data from a large randomized controlled trial.36 We selected patient level factors as potential treatment effect modifiers based on influential relationships with LBP clinical outcomes previously reported in the literature. We acknowledge that certain selected factors did have potential to change during the course of treatment (ie, number of pain medications and recovery expectations); however including such factors in these analyses would potentially enhance the ability to characterize patients at baseline.

The aims of this study were exploratory following methodological criteria for moderator analysis suggested by Pincus et al.59 Specifically, this current study is a secondary ‘post-hoc’ analysis with findings provided for hypothesis generating purposes as there was no pre-specified ‘a-priori’ moderator effect size reported in the original trial protocol. Our exploratory results provide important hypothesis generating information for future clinical trials which are needed43 and may have specific implications for studies evaluating the clinical effectiveness of stratified care for LBP. Our findings reflect exploratory evidence that should be interpreted with caution and not considered as confirmatory as the factors selected for this secondary analysis were based on theory and previous research.59 For example, lower education level8, 16, 76 and increased number of pain medications23, 51 have demonstrated prognostic capabilities for musculoskeletal pain related clinical outcomes in previous studies, however were only identified as having weak evidence to modify treatment response in our analysis. Future studies are required to confirm these findings prior to changes in clinical practice.

We were not adequately powered to analyze the influence of three-way interactions on poor outcome, which is disappointing as those findings may have provided further perspective to our findings. For example, incorporating three-way [treatment x SES x initial STarT Back tool risk subgroup] interaction terms into our logistic regression models may have provided preliminary support for stratified care being least effective for those patients at low SES also identified as at high risk of persistent pain. Therefore, we were not able to fully establish if stratified care was more beneficial for high SES participants or less beneficial for low SES participants and if so how these relationships were potentially influenced by other factors (eg, risk subgroup, work satisfaction, recovery expectations). Previous suggestions are that there should be a minimum of at least 20 individuals in the smallest group when conducting subgroup analyses59 and many cell counts in this current study did not achieve this criterion when comparing the proportion of patients with poor outcome by SES across initial risk subgroup (or other factors included in these analyses).

We also acknowledge the relative strengths and weaknesses associated with our analyses that used an absolute cut point (≥7) as opposed to RMDQ change scores and the potential effect this may have on our conclusions. Our decision for using the ≥7 RMDQ cut point allows for direct comparisons to previous studies,34, 77 while alsof considering the optimal method for analyzing responsiveness to LBP interventions is debatable. Recent recommendations include reporting the cumulative distribution of responses for treatment and control groups to provide the proportion of patients at each scale score who experience change at that level or better,18 however such an approach may be difficult to interpret group interactions. Others have suggested 30% improvement from baseline to be a useful threshold for identifying clinically meaningful improvement,58 however these methods are also associated with limitations.20 Our decision to use an absolute cut point is consistent with previous studies involving the STarT Back Tool34, 77 and is a common method to assess LBP recovery,40 however may be associated with several limitations including loss of statistical power and increased potential for type I and II errors.37 Moreover, we were not able to determine if patient perspectives of poor outcome at 4 months was consistent with the RMDQ cut point used in this study.

For this secondary analysis, SES was assessed using the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC) reduced method which is primarily based on job occupation, however we acknowledge that SES has been defined as a multidimensional construct that is commonly measured in health services research as a combination of education, income, and occupation.2 Our rationale for using the NS-SEC reduced method, which collapses SES into three potential classes, was primarily based on the observation of extremely low cell counts when using alternative NS-SEC methods that collapse SES into eight potential classes. Although job occupation has been indicated as a valid proxy indicator for SES,1 we acknowledge that the method used in this analysis did not specifically account for other important indicators such as education and income when classifying SES. We did however observe a trend for level of education as a treatment effect modifier providing further support to the SES finding.

Comparison to Other Studies

Comparison of our findings to others should be done with caution as previous studies have not focused on evaluating the influence of non-modifiable patient level factors for LBP treatment effect modification and have used alternative statistical methods.24, 49, 68 Previous studies have commonly used linear regression and incorporated specific thresholds (eg, one standard deviation change from baseline) to aid interpretation of the magnitude of treatment effect modification and determine clinically important interaction effects. Collectively, many of those studies have found that although most factors predicted outcomes regardless of treatment (indicating prognostic capabilities), very few were able to predict response to a particular treatment (indicating treatment effect modification). We used logistic regression because the treatment response outcome was dichotomous (RMDQ ≥7) and reported all interactions with a p-value ≤0.20 to ensure that all potential modifiers were identified similar to the approach used by Gurung et al.,28 however support for treatment effect modification was reduced when using linear regression modelling strategies.

Future studies should be designed and powered so they have the ability to distinguish between factors that demonstrate prognostic or treatment effect modification capabilities (or both) to further inform clinical reasoning.35, 37 We also recognize that for future randomized controlled trials to be adequately powered for robust detection of treatment effect modification, the sample size required should be increased at least fourfold the required sample size to detect main treatment effects,5, 59 presenting a key challenge to research planning, funding and delivery.

Meaning of the Study: Implications for Clinicians

We have provided preliminary findings for SES, level of education, and number of pain medications as potential treatment effect modifiers for LBP prognostic stratified care; however future studies are required to confirm these findings prior to changing clinical practice. If our findings are validated in future studies, the outcomes from stratified care may be improved through greater tailoring of stratified care for specific patient characteristics. For example, development of an enhanced treatment that better supports and meets the needs of low SES patients who are at high risk of persistent disability may provide a beneficial treatment option for this population.

Future Research

Future studies should evaluate complex interactions that may exist between factors identified in this analysis and other potentially influential patient characteristics (eg, health literacy, health knowledge, and motivation) that may be modified with treatment. For example, the feasibility of developing enhanced treatments that better meet the needs of low SES patients has strong potential to inform planning of future studies capable of informing best practice. Collectively, findings from this study provide additional support for future LBP trials to include SES, education, and pain medications as a means to define subgroups and evaluate treatment effect modification.

Highlights.

We conducted a secondary analysis to identify treatment-effect modifiers within the STarT Back Trial at 4 months follow-up.

Socioeconomic status was identified as an effect modifier for disability outcomes with education level and number of pain medications meeting criteria for effect modification with weaker evidence.

We have provided preliminary exploratory findings about characteristics of patients who might least likely benefit from prognostic stratified care treatment for low back pain.

Acknowledgments

Research funding: Jason Beneciuk was supported by the American National Institutes of Health (NIH) Rehabilitation Research Career Development Program (K12-HD055929). Nadine Foster and Jonathan Hill are supported through a UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research Professorship awarded to Nadine Foster (NIHR-RP-011-015). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIH, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Arthritis Research UK funded the STarT Back Trial (grant code 17741). We thank all the participants and general practices who participated in the STarT Back trial; and NHS Stoke-on-Trent and North Staffordshire for hosting the trial, and the North Staffordshire Primary Care Research Consortium and the primary care delivery arm of West Midlands North Comprehensive Local Research Network for service support funding. The authors declare no conflicts of interest exist.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could a3ect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2002;21:60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychological Association. Report of the APA Task Force on Socioeconomic Status. Washington, DC: 2007. Availiable at: http://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/index.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartley EJ, Fillingim RB. Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. British journal of anaesthesia. 2013;111:52–58. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, Cleland JA. Individual expectation: an overlooked, but pertinent, factor in the treatment of individuals experiencing musculoskeletal pain. Physical therapy. 2010;90:1345–1355. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brookes ST, Whitely E, Egger M, Smith GD, Mulheran PA, Peters TJ. Subgroup analyses in randomized trials: risks of subgroup-specific analyses; power and sample size for the interaction test. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2004;57:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke A, Nahin RL, Stussman BJ. Limited Health Knowledge as a Reason for Non-Use of Four Common Complementary Health Practices. PloS one. 2015;10:e0129336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke JF, Sussman JB, Kent DM, Hayward RA. Three simple rules to ensure reasonably credible subgroup analyses. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2015;351:h5651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell P, Foster NE, Thomas E, Dunn KM. Prognostic indicators of low back pain in primary care: five-year prospective study. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2013;14:873–883. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr JL, Klaber Moffett JA, Howarth E, Richmond SJ, Torgerson DJ, Jackson DA, Metcalfe CJ. A randomized trial comparing a group exercise programme for back pain patients with individual physiotherapy in a severely deprived area. Disability and rehabilitation. 2005;27:929–937. doi: 10.1080/09638280500030639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr JL, Moffett JA. The impact of social deprivation on chronic back pain outcomes. Chronic illness. 2005;1:121–129. doi: 10.1177/17423953050010020901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman JR, Norvell DC, Hermsmeyer JT, Bransford RJ, DeVine J, McGirt MJ, Lee MJ. Evaluating common outcomes for measuring treatment success for chronic low back pain. Spine. 2011;36:S54–68. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31822ef74d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Avins AL, Erro JH, Ichikawa L, Barlow WE, Delaney K, Hawkes R, Hamilton L, Pressman A, Khalsa PS, Deyo RA. A randomized trial comparing acupuncture, simulated acupuncture, and usual care for chronic low back pain. Archives of internal medicine. 2009;169:858–866. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chesser A, Burke A, Reyes J, Rohrberg T. Navigating the digital divide: A systematic review of eHealth literacy in underserved populations in the United States. Informatics for health & social care. 2016;41:1–19. doi: 10.3109/17538157.2014.948171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costa-Black KM, Loisel P, Anema JR, Pransky G. Back pain and work. Best practice & research. Clinical rheumatology. 2010;24:227–240. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.da Costa LC, Koes BW, Pransky G, Borkan J, Maher CG, Smeets RJ. Primary care research priorities in low back pain: an update. Spine. 2013;38:148–156. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318267a92f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.da Costa LC, Maher CG, McAuley JH, Hancock MJ, Herbert RD, Refshauge KM, Henschke N. Prognosis for patients with chronic low back pain: inception cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2009;339:b3829. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damush TM, Weinberger M, Perkins SM, Rao JK, Tierney WM, Qi R, Clark DO. The long-term effects of a self-management program for inner-city primary care patients with acute low back pain. Archives of internal medicine. 2003;163:2632–2638. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.21.2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, Andersson G, Borenstein D, Carragee E, Carrino J, Chou R, Cook K, DeLitto A, Goertz C, Khalsa P, Loeser J, Mackey S, Panagis J, Rainville J, Tosteson T, Turk D, Von Korff M, Weiner DK. Report of the NIH Task Force on research standards for chronic low back pain. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2014;15:569–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans SD, Sheffer CE, Bickel WK, Cottoms N, Olson M, Piti LP, Austin T, Stayna H. The Process of Adapting the Evidence-Based Treatment for Tobacco Dependence for Smokers of Lower Socioeconomic Status. Journal of addiction research & therapy. 2015;6 doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferreira ML, Herbert RD, Ferreira PH, Latimer J, Ostelo RW, Nascimento DP, Smeets RJ. A critical review of methods used to determine the smallest worthwhile effect of interventions for low back pain. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2012;65:253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL., 3rd Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2009;10:447–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster NE, Bishop A, Thomas E, Main C, Horne R, Weinman J, Hay E. Illness perceptions of low back pain patients in primary care: what are they, do they change and are they associated with outcome? Pain. 2008;136:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fried TR, O'Leary J, Towle V, Goldstein MK, Trentalange M, Martin DK. Health outcomes associated with polypharmacy in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62:2261–2272. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia AN, Costa LD, Hancock M, Costa LO. Identifying Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain Who Respond Best to Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Physical therapy. 2015 doi: 10.2522/ptj.20150295. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, Naganathan V, Waite L, Seibel MJ, McLachlan AJ, Cumming RG, Handelsman DJ, Le Couteur DG. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2012;65:989–995. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green JL, Hawley JN, Rask KJ. Is the number of prescribing physicians an independent risk factor for adverse drug events in an elderly outpatient population? The American journal of geriatric pharmacotherapy. 2007;5:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grotle M, Foster NE, Dunn KM, Croft P. Are prognostic indicators for poor outcome different for acute and chronic low back pain consulters in primary care? Pain. 2010;151:790–797. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurung T, Ellard DR, Mistry D, Patel S, Underwood M. Identifying potential moderators for response to treatment in low back pain: A systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2015;101:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hallegraeff JM, Krijnen WP, van der Schans CP, de Greef MH. Expectations about recovery from acute non-specific low back pain predict absence from usual work due to chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Journal of physiotherapy. 2012;58:165–172. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hancock M, Herbert RD, Maher CG. A guide to interpretation of studies investigating subgroups of responders to physical therapy interventions. Physical therapy. 2009;89:698–704. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hay EM, Dunn KM, Hill JC, Lewis M, Mason EE, Konstantinou K, Sowden G, Somerville S, Vohora K, Whitehurst D, Main CJ. A randomised clinical trial of subgrouping and targeted treatment for low back pain compared with best current care. The STarT Back Trial Study Protocol. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2008;9:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayden JA, Chou R, Hogg-Johnson S, Bombardier C. Systematic reviews of low back pain prognosis had variable methods and results: guidance for future prognosis reviews. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2009;62:781–796. e781. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Bleasel J, York J, Das A, McAuley JH. Prognosis in patients with recent onset low back pain in Australian primary care: inception cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2008;337:a171. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hill JC, Dunn KM, Lewis M, Mullis R, Main CJ, Foster NE, Hay EM. A primary care back pain screening tool: identifying patient subgroups for initial treatment. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2008;59:632–641. doi: 10.1002/art.23563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill JC, Fritz JM. Psychosocial influences on low back pain, disability, and response to treatment. Physical therapy. 2011;91:712–721. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M, Bryan S, Dunn KM, Foster NE, Konstantinou K, Main CJ, Mason E, Somerville S, Sowden G, Vohora K, Hay EM. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1560–1571. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60937-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hingorani AD, Windt DA, Riley RD, Abrams K, Moons KG, Steyerberg EW, Schroter S, Sauerbrei W, Altman DG, Hemingway H, Group P. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 4: stratified medicine research. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2013;346:e5793. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnell K, Klarin I. The relationship between number of drugs and potential drug-drug interactions in the elderly: a study of over 600,000 elderly patients from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. Drug safety. 2007;30:911–918. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200730100-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jordan KP, Thomas E, Peat G, Wilkie R, Croft P. Social risks for disabling pain in older people: a prospective study of individual and area characteristics. Pain. 2008;137:652–661. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamper SJ, Stanton TR, Williams CM, Maher CG, Hush JM. How is recovery from low back pain measured? A systematic review of the literature. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2011;20:9–18. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1477-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kent P, Keating JL, Leboeuf-Yde C. Research methods for subgrouping low back pain. BMC medical research methodology. 2010;10:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kongsted A, Vach W, Axo M, Bech RN, Hestbaek L. Expectation of recovery from low back pain: a longitudinal cohort study investigating patient characteristics related to expectations and the association between expectations and 3-month outcome. Spine. 2014;39:81–90. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kraemer HC, Frank E, Kupfer DJ. Moderators of treatment outcomes: clinical, research, and policy importance. Jama. 2006;296:1286–1289. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.10.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of general psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuyken W, Hayes R, Barrett B, Byng R, Dalgleish T, Kessler D, Lewis G, Watkins E, Brejcha C, Cardy J, Causley A, Cowderoy S, Evans A, Gradinger F, Kaur S, Lanham P, Morant N, Richards J, Shah P, Sutton H, Vicary R, Weaver A, Wilks J, Williams M, Taylor RS, Byford S. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:63–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lamb SE, Lall R, Hansen Z, Castelnuovo E, Withers EJ, Nichols V, Griffiths F, Potter R, Szczepura A, Underwood M, Be STtg. A multicentred randomised controlled trial of a primary care-based cognitive behavioural programme for low back pain. The Back Skills Training (BeST) trial. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England) 2010;14:1–253. iii–iv. doi: 10.3310/hta14410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Linton SJ. Occupational psychological factors increase the risk for back pain: a systematic review. Journal of occupational rehabilitation. 2001;11:53–66. doi: 10.1023/a:1016656225318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luijks H, Biermans M, Bor H, van Weel C, Lagro-Janssen T, de Grauw W, Schermer T. The Effect of Comorbidity on Glycemic Control and Systolic Blood Pressure in Type 2 Diabetes: A Cohort Study with 5 Year Follow-Up in Primary Care. PloS one. 2015;10:e0138662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macedo LG, Maher CG, Hancock MJ, Kamper SJ, McAuley JH, Stanton TR, Stafford R, Hodges PW. Predicting response to motor control exercises and graded activity for patients with low back pain: preplanned secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Physical therapy. 2014;94:1543–1554. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20140014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Macfarlane GJ, Pallewatte N, Paudyal P, Blyth FM, Coggon D, Crombez G, Linton S, Leino-Arjas P, Silman AJ, Smeets RJ, van der Windt D. Evaluation of work-related psychosocial factors and regional musculoskeletal pain: results from a EULAR Task Force. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2009;68:885–891. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.090829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Makris UE, Pugh MJ, Alvarez CA, Berlowitz DR, Turner BJ, Aung K, Mortensen EM. Exposure to High-Risk Medications is Associated With Worse Outcomes in Older Veterans With Chronic Pain. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2015;350:279–285. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moffett JA, Underwood MR, Gardiner ED. Socioeconomic status predicts functional disability in patients participating in a back pain trial. Disability and rehabilitation. 2009;31:783–790. doi: 10.1080/09638280802309327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murray CJ, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, Abbasoglu Ozgoren A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Aboyans V, Abraham JP, Abubakar I, Abu-Raddad LJ, Abu-Rmeileh NM, Achoki T, Ackerman IN, Ademi Z, Adou AK, Adsuar JC, Afshin A, Agardh EE, Alam SS, Alasfoor D, Albittar MI, Alegretti MA, Alemu ZA, Alfonso-Cristancho R, Alhabib S, Ali R, Alla F, Allebeck P, Almazroa MA, Alsharif U, Alvarez E, Alvis-Guzman N, Amare AT, Ameh EA, Amini H, Ammar W, Anderson HR, Anderson BO, Antonio CA, Anwari P, Arnlöv J, Arsic Arsenijevic VS, Artaman A, Asghar RJ, Assadi R, Atkins LS, Avila MA, Awuah B, Bachman VF, Badawi A, Bahit MC, Balakrishnan K, Banerjee A, Barker-Collo SL, Barquera S, Barregard L, Barrero LH, Basu A, Basu S, Basulaiman MO, Beardsley J, Bedi N, Beghi E, Bekele T, Bell ML, Benjet C, Bennett DA, Bensenor IM, Benzian H, Bernabé E, Bertozzi-Villa A, Beyene TJ, Bhala N, Bhalla A, Bhutta ZA, Bienhoff K, Bikbov B, Biryukov S, Blore JD, Blosser CD, Blyth FM, Bohensky MA, Bolliger IW, Bora Başara B, Bornstein NM, Bose D, Boufous S, Bourne RR, Boyers LN, Brainin M, Brayne CE, Brazinova A, Breitborde NJ, Brenner H, Briggs AD, Brooks PM, Brown JC, Brugha TS, Buchbinder R, Buckle GC, Budke CM, Bulchis A, Bulloch AG, Campos-Nonato IR, Carabin H, Carapetis JR, Cárdenas R, Carpenter DO, Caso V, Castañeda-Orjuela CA, Castro RE, Catalá-López F, Cavalleri F, Çavlin A, Chadha VK, Chang JC, Charlson FJ, Chen H, Chen W, Chiang PP, Chimed-Ochir O, Chowdhury R, Christensen H, Christophi CA, Cirillo M, Coates MM, Coffeng LE, Coggeshall MS, Colistro V, Colquhoun SM, Cooke GS, Cooper C, Cooper LT, Coppola LM, Cortinovis M, Criqui MH, Crump JA, Cuevas-Nasu L, Danawi H, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dansereau E, Dargan PI, Davey G, Davis A, Davitoiu DV, Dayama A, De Leo D, Degenhardt L, Del Pozo-Cruz B, Dellavalle RP, Deribe K, Derrett S, Des Jarlais DC, Dessalegn M, Dharmaratne SD, Dherani MK, Diaz-Torné C, Dicker D, Ding EL, Dokova K, Dorsey ER, Driscoll TR, Duan L, Duber HC, Ebel BE, Edmond KM, Elshrek YM, Endres M, Ermakov SP, Erskine HE, Eshrati B, Esteghamati A, Estep K, Faraon EJ, Farzadfar F, Fay DF, Feigin VL, Felson DT, Fereshtehnejad SM, Fernandes JG, Ferrari AJ, Fitzmaurice C, Flaxman AD, Fleming TD, Foigt N, Forouzanfar MH, Fowkes FG, Paleo UF, Franklin RC, Fürst T, Gabbe B, Gaffikin L, Gankpé FG, Geleijnse JM, Gessner BD, Gething P, Gibney KB, Giroud M, Giussani G, Gomez Dantes H, Gona P, González-Medina D, Gosselin RA, Gotay CC, Goto A, Gouda HN, Graetz N, Gugnani HC, Gupta R, Gupta R, Gutiérrez RA, Haagsma J, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hagan H, Halasa YA, Hamadeh RR, Hamavid H, Hammami M, Hancock J, Hankey GJ, Hansen GM, Hao Y, Harb HL, Haro JM, Havmoeller R, Hay SI, Hay RJ, Heredia-Pi IB, Heuton KR, Heydarpour P, Higashi H, Hijar M, Hoek HW, Hoffman HJ, Hosgood HD, Hossain M, Hotez PJ, Hoy DG, Hsairi M, Hu G, Huang C, Huang JJ, Husseini A, Huynh C, Iannarone ML, Iburg KM, Innos K, Inoue M, Islami F, Jacobsen KH, Jarvis DL, Jassal SK, Jee SH, Jeemon P, Jensen PN, Jha V, Jiang G, Jiang Y, Jonas JB, Juel K, Kan H, Karch A, Karema CK, Karimkhani C, Karthikeyan G, Kassebaum NJ, Kaul A, Kawakami N, Kazanjan K, Kemp AH, Kengne AP, Keren A, Khader YS, Khalifa SE, Khan EA, Khan G, Khang YH, Kieling C, Kim D, Kim S, Kim Y, Kinfu Y, Kinge JM, Kivipelto M, Knibbs LD, Knudsen AK, Kokubo Y, Kosen S, Krishnaswami S, Kuate Defo B, Kucuk Bicer B, Kuipers EJ, Kulkarni C, Kulkarni VS, Kumar GA, Kyu HH, Lai T, Lalloo R, Lallukka T, Lam H, Lan Q, Lansingh VC, Larsson A, Lawrynowicz AE, Leasher JL, Leigh J, Leung R, Levitz CE, Li B, Li Y, Li Y, Lim SS, Lind M, Lipshultz SE, Liu S, Liu Y, Lloyd BK, Lofgren KT, Logroscino G, Looker KJ, Lortet-Tieulent J, Lotufo PA, Lozano R, Lucas RM, Lunevicius R, Lyons RA, Ma S, Macintyre MF, Mackay MT, Majdan M, Malekzadeh R, Marcenes W, Margolis DJ, Margono C, Marzan MB, Masci JR, Mashal MT, Matzopoulos R, Mayosi BM, Mazorodze TT, Mcgill NW, Mcgrath JJ, Mckee M, Mclain A, Meaney PA, Medina C, Mehndiratta MM, Mekonnen W, Melaku YA, Meltzer M, Memish ZA, Mensah GA, Meretoja A, Mhimbira FA, Micha R, Miller TR, Mills EJ, Mitchell PB, Mock CN, Mohamed Ibrahim N, Mohammad KA, Mokdad AH, Mola GL, Monasta L, Montañez Hernandez JC, Montico M, Montine TJ, Mooney MD, Moore AR, Moradi-Lakeh M, Moran AE, Mori R, Moschandreas J, Moturi WN, Moyer ML, Mozaffarian D, Msemburi WT, Mueller UO, Mukaigawara M, Mullany EC, Murdoch ME, Murray J, Murthy KS, Naghavi M, Naheed A, Naidoo KS, Naldi L, Nand D, Nangia V, Narayan KM, Nejjari C, Neupane SP, Newton CR, Ng M, Ngalesoni FN, Nguyen G, Nisar MI, Nolte S, Norheim OF, Norman RE, Norrving B, Nyakarahuka L, Oh IH, Ohkubo T, Ohno SL, Olusanya BO, Opio JN, Ortblad K, Ortiz A, Pain AW, Pandian JD, Panelo CI, Papachristou C, Park EK, Park JH, Patten SB, Patton GC, Paul VK, Pavlin BI, Pearce N, Pereira DM, Perez-Padilla R, Perez-Ruiz F, Perico N, Pervaiz A, Pesudovs K, Peterson CB, Petzold M, Phillips MR, Phillips BK, Phillips DE, Piel FB, Plass D, Poenaru D, Polinder S, Pope D, Popova S, Poulton RG, Pourmalek F, Prabhakaran D, Prasad NM, Pullan RL, Qato DM, Quistberg DA, Rafay A, Rahimi K, Rahman SU, Raju M, Rana SM, Razavi H, Reddy KS, Refaat A, Remuzzi G, Resnikoff S, Ribeiro AL, Richardson L, Richardus JH, Roberts DA, Rojas-Rueda D, Ronfani L, Roth GA, Rothenbacher D, Rothstein DH, Rowley JT, Roy N, Ruhago GM, Saeedi MY, Saha S, Sahraian MA, Sampson UK, Sanabria JR, Sandar L, Santos IS, Satpathy M, Sawhney M, Scarborough P, Schneider IJ, Schöttker B, Schumacher AE, Schwebel DC, Scott JG, Seedat S, Sepanlou SG, Serina PT, Servan-Mori EE, Shackelford KA, Shaheen A, Shahraz S, Shamah Levy T, Shangguan S, She J, Sheikhbahaei S, Shi P, Shibuya K, Shinohara Y, Shiri R, Shishani K, Shiue I, Shrime MG, Sigfusdottir ID, Silberberg DH, Simard EP, Sindi S, Singh A, Singh JA, Singh L, Skirbekk V, Slepak EL, Sliwa K, Soneji S, Ss_etseq;reide K, Soshnikov S, Sposato LA, Sreeramareddy CT, Stanaway JD, Stathopoulou V, Stein DJ, Stein MB, Steiner C, Steiner TJ, Stevens A, Stewart A, Stovner LJ, Stroumpoulis K, Sunguya BF, Swaminathan S, Swaroop M, Sykes BL, Tabb KM, Takahashi K, Tandon N, Tanne D, Tanner M, Tavakkoli M, Taylor HR, Te Ao BJ, Tediosi F, Temesgen AM, Templin T, Ten Have M, Tenkorang EY, Terkawi AS, Thomson B, Thorne-Lyman AL, Thrift AG, Thurston GD, Tillmann T, Tonelli M, Topouzis F, Toyoshima H, Traebert J, Tran BX, Trillini M, Truelsen T, Tsilimbaris M, Tuzcu EM, Uchendu US, Ukwaja KN, Undurraga EA, Uzun SB, Van Brakel WH, Van De Vijver S, van Gool CH, Van Os J, Vasankari TJ, Venketasubramanian N, Violante FS, Vlassov VV, Vollset SE, Wagner GR, Wagner J, Waller SG, Wan X, Wang H, Wang J, Wang L, Warouw TS, Weichenthal S, Weiderpass E, Weintraub RG, Wenzhi W, Werdecker A, Westerman R, Whiteford HA, Wilkinson JD, Williams TN, Wolfe CD, Wolock TM, Woolf AD, Wulf S, Wurtz B, Xu G, Yan LL, Yano Y, Ye P, Yentetseq;r GK, Yip P, Yonemoto N, Yoon SJ, Younis MZ, Yu C, Zaki ME, Zhao Y, Zheng Y, Zonies D, Zou X, Salomon JA, Lopez AD, Vos T. Global, regional, and national disabilityadjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990ovs;2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet. 2015;386:2145–2191. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61340-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Myers SS, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Cherkin DC, Legedza A, Kaptchuk TJ, Hrbek A, Buring JE, Post D, Connelly MT, Eisenberg DM. Patient expectations as predictors of outcome in patients with acute low back pain. Journal of general internal medicine. 2008;23:148–153. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0460-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newton JN, Briggs AD, Murray CJ, Dicker D, Foreman KJ, Wang H, Naghavi M, Forouzanfar MH, Ohno SL, Barber RM, Vos T, Stanaway JD, Schmidt JC, Hughes AJ, Fay DF, Ecob R, Gresser C, McKee M, Rutter H, Abubakar I, Ali R, Anderson HR, Banerjee A, Bennett DA, Bernabé E, Bhui KS, Biryukov SM, Bourne RR, Brayne CE, Bruce NG, Brugha TS, Burch M, Capewell S, Casey D, Chowdhury R, Coates MM, Cooper C, Critchley JA, Dargan PI, Dherani MK, Elliott P, Ezzati M, Fenton KA, Fraser MS, Fürst T, Greaves F, Green MA, Gunnell DJ, Hannigan BM, Hay RJ, Hay SI, Hemingway H, Larson HJ, Looker KJ, Lunevicius R, Lyons RA, Marcenes W, Mason-Jones AJ, Matthews FE, Moller H, Murdoch ME, Newton CR, Pearce N, Piel FB, Pope D, Rahimi K, Rodriguez A, Scarborough P, Schumacher AE, Shiue I, Smeeth L, Tedstone A, Valabhji J, Williams HC, Wolfe CD, Woolf AD, Davis AC. Changes in health in England, with analysis by English regions and areas of deprivation, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:2257–2274. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00195-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Office of National Statistics. [Accessed October 15, 2015];National Statistics Socio-economic classification (NS-SEC rebased on SOC2010) Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105160709/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/classifications/current-standard-classifications/soc2010/soc2010-volume-3-ns-sec--rebased-on-soc2010--user-manual/index.html#top.

- 57.Office of National Statistics. [Accessed October 15, 2015];Education and Training Statistics for the United Kingdom. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/education-and-training-statistics-for-the-uk-2012.

- 58.Ostelo RW, Deyo RA, Stratford P, Waddell G, Croft P, Von Korff M, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine. 2008;33:90–94. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e3a10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pincus T, Miles C, Froud R, Underwood M, Carnes D, Taylor SJ. Methodological criteria for the assessment of moderators in systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials: a consensus study. BMC medical research methodology. 2011;11:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pransky G, Borkan JM, Young AE, Cherkin DC. Are we making progress?: the tenth international forum for primary care research on low back pain. Spine. 2011;36:1608–1614. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f6114e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reid MC, Bennett DA, Chen WG, Eldadah BA, Farrar JT, Ferrell B, Gallagher RM, Hanlon JT, Herr K, Horn SD, Inturrisi CE, Lemtouni S, Lin YW, Michaud K, Morrison RS, Neogi T, Porter LL, Solomon DH, Von Korff M, Weiss K, Witter J, Zacharoff KL. Improving the pharmacologic management of pain in older adults: identifying the research gaps and methods to address them. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass) 2011;12:1336–1357. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Riley JL, III, Wade JB, Robinson ME, Price DD. The stages of pain processing across the adult lifespan. The Journal of Pain. 2000;1:162–170. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rodeghero JR, Cook CE, Cleland JA, Mintken PE. Risk stratification of patients with low back pain seen in physical therapy practice. Manual therapy. 2015;20:855–860. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine. 1983;8:141–144. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198303000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rothwell PM. Treating individuals 2. Subgroup analysis in randomised controlled trials: importance, indications, and interpretation. Lancet. 2005;365:176–186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17709-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rundell SD, Sherman KJ, Heagerty PJ, Mock CN, Jarvik JG. The clinical course of pain and function in older adults with a new primary care visit for back pain. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2015;63:524–530. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sheffer CE, Stitzer M, Landes R, Brackman SL, Munn T, Moore P. Socioeconomic disparities in community-based treatment of tobacco dependence. American journal of public health. 2012;102:e8–16. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smeets RJ, Maher CG, Nicholas MK, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD. Do psychological characteristics predict response to exercise and advice for subacute low back pain? Arthritis and rheumatism. 2009;61:1202–1209. doi: 10.1002/art.24731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sun X, Briel M, Walter SD, Guyatt GH. Is a subgroup effect believable? Updating criteria to evaluate the credibility of subgroup analyses. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2010;340:c117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Swearingen CJ, McCollum L, Daltroy LH, Pincus T, Dewalt DA, Davis TC. Screening for low literacy in a rheumatology setting: more than 10% of patients cannot read "cartilage," "diagnosis," "rheumatologist," or "symptom". Journal of clinical rheumatology : practical reports on rheumatic & musculoskeletal diseases. 2010;16:359–364. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181fe8ab1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Team UBT. United Kingdom back pain exercise and manipulation (UK BEAM) randomised trial: effectiveness of physical treatments for back pain in primary care. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2004;329:1377. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38282.669225.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thorn BE, Day MA, Burns J, Kuhajda MC, Gaskins SW, Sweeney K, McConley R, Ward LC, Cabbil C. Randomized trial of group cognitive behavioral therapy compared with a pain education control for low-literacy rural people with chronic pain. Pain. 2011;152:2710–2720. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Valencia C, Robinson ME, George SZ. Socioeconomic status influences the relationship between fear-avoidance beliefs work and disability. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass) 2011;12:328–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van den Bos GA, Smits JP, Westert GP, van Straten A. Socioeconomic variations in the course of stroke: unequal health outcomes, equal care? Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2002;56:943–948. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.12.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Varghese M, Sheffer C, Stitzer M, Landes R, Brackman SL, Munn T. Socioeconomic disparities in telephone-based treatment of tobacco dependence. American journal of public health. 2014;104:e76–84. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Verkerk K, Luijsterburg PA, Heymans MW, Ronchetti I, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Miedema HS, Koes BW. Prognosis and course of disability in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a 5- and 12-month follow-up cohort study. Physical therapy. 2013;93:1603–1614. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wideman TH, Hill JC, Main CJ, Lewis M, Sullivan MJ, Hay EM. Comparing the responsiveness of a brief, multidimensional risk screening tool for back pain to its unidimensional reference standards: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Pain. 2012;153:2182–2191. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Witt CM, Schutzler L, Ludtke R, Wegscheider K, Willich SN. Patient characteristics and variation in treatment outcomes: which patients benefit most from acupuncture for chronic pain? The Clinical journal of pain. 2011;27:550–555. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31820dfbf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]