Abstract

Background

Racial/ethnic minorities bear a disproportionate burden of alcohol-related problems in the U.S. It is unknown whether this reflects harmful patterns of lifecourse heavy drinking. Prior research shows little support for the latter but has been limited to young samples. We examine racial/ethnic differences in heavy drinking trajectories from ages 21 to 51.

Methods

Data on heavy drinking (6+ drinks/occasion) are from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (N=9,468), collected between 1982 and 2012. Sex-stratified, generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to model heavy drinking frequency trajectories as a function of age with a cubic curve, and interactions of race with age terms were tested to assess racial/ethnic differences. Models adjusted for time-varying socioeconomic status and marital and parenting status; predictors of trajectories were examined in race- and sex-specific models.

Results

White men and women had similarly steep declines in heavy drinking frequency throughout the 20s, contrasting with slower declines (and lower peaks) in Black and Hispanic men and women. During the 30s there was a Hispanic-White crossover in men’s heavy drinking curves, and a Black-White female crossover among lifetime heavy drinkers; by age 51, racial/ethnic group trajectories converged in both sexes. Greater education was protective for all groups.

Conclusion

Observed racial/ethnic crossovers in heavy drinking frequency following young adulthood might contribute to disparities in alcohol-related problems in middle adulthood, and suggest a need for targeted interventions during this period. Additionally, interventions that increase educational attainment may constitute an important strategy for reducing heavy drinking in all groups.

Keywords: longitudinal analysis, racial/ethnic disparities, heavy drinking

1. INTRODUCTION

Racial/ethnic minorities bear a disproportionate burden of alcohol-related morbidity and mortality in the U.S. (Greenfield, 2001; Hilton, 2006; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), 2001; Stinson et al., 1993; Yoon and Yi, 2007). Compared to Whites, Black and Hispanic drinkers are at greater risk for negative drinking consequences and alcohol dependence symptoms (Caetano and Clark, 1998; Greenfield et al., 2003; Herd, 1994), as well as later alcohol use disorder onset and persistence (Grant et al., 2012). They also have higher rates of alcoholic liver disease (Chartier and Caetano, 2010), with Hispanics showing earlier onset and more severe consequences than Whites (Levy et al., 2015; Polednak, 2008; Yoon et al., 2011). Such disparities appear somewhat paradoxical given the lower or similar rates of heavy drinking and alcohol disorders in Blacks and Hispanics compared to Whites (Grant et al., 2015). This seeming discrepancy might be explained by differential abstention and access to alcohol interventions (Dawson et al., 2015; Mulia et al., 2014a), as well as possible differences in lifecourse drinking patterns.

Information on long-term heavy drinking, in particular, might shed light on disparities in conditions that often develop after years of heavy drinking, such as alcohol dependence and alcoholic liver disease, yet such data are uncommon. Much of what is known about long-term drinking patterns comes from developmental studies indicating that drinking commonly begins in adolescence, increases and peaks in the early twenties, and decreases thereafter (Chen and Jacobson, 2012; Maggs and Schulenberg, 2004/2005). While different types of alcohol trajectories have been observed (e.g., Capaldi et al., 2013; Casswell et al., 2002; Jackson and Sher, 2005; Sher et al., 2011; Warner et al., 2007), a pattern of “aging out” of heavy drinking is normative (Karlamangla et al., 2006; White and Jackson, 2004–2005).

There are, however, some indications that “aging out” may differ across race. In contrast to White heavy drinking prevalence rates that rise and fall significantly during the twenties, Black heavy drinking rates climb slowly and plateau in the late 20s (Godette et al., 2006). Further, two studies based on the U.S. National Alcohol Survey (NAS) suggest more prolonged heavy drinking among minorities. In a 1992 follow-up of a 1984 sample of heavy drinkers, Hispanics and Blacks evidenced longer heavy drinking careers than Whites (Caetano and Kaskutas, 1995), and a recent analysis of the 2009-10 NAS found that Hispanic men and Black women had greater relative risks for persistent (vs. declining) heavy drinking compared to Whites (Mulia et al., in press).

Prospective longitudinal data are needed to confirm such patterns and determine whether and how racial/ethnic groups differ in lifetime heavy drinking. The sparse research examining this question has yielded mixed findings, however. Using time-varying effect models to analyze data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (AddHealth), Evans-Polce et al. (2015) found that White heavy drinking rose steeply to age 21 then declined, while Hispanic and Black trajectories remained comparatively flat or increased slightly throughout the 20s. By age 30, White and Hispanic heavy drinking converged, but Whites still exceeded Blacks in heavy drinking. A second AddHealth study by Keyes et al. (2015) examined sex-stratified, difference-in-differences models and showed consistently greater consumption in Whites compared to Blacks; the authors speculated about possible convergence in White and Black men’s risky drinking beyond the ages observed. In a third study, Chen et al.’s (2012) multilevel analysis showed a clear convergence in heavy drinking frequency of all three racial/ethnic groups by the early 30s. This is similar to Muthén and Muthén’s (2000) results based on the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) and Cooper et al.’s (2008) longitudinal findings, which both showed eventual Black-White convergence in heavy drinking frequency.

While these studies indicate some racial/ethnic differences in “aging out” of heavy drinking, there is little evidence of more prolonged heavy drinking by minorities. However, nearly all of these studies ended with young adulthood. The exception was the NLSY study which followed individuals to age 37 and revealed both an upward trend in Black heavy drinking and a “crossover” in alcohol problems, with Blacks surpassing Whites and Hispanics in the mid-30s (Muthén and Muthén, 2000). This raises the question of whether longer follow-up might yield a different picture of racial/ethnic drinking patterns that could further understanding alcohol-related health disparities in middle adulthood. Additionally, the findings of Keyes et al. (2015) suggest the need to consider sex-specific trajectories.

The current study aims to address these questions by examining the heavy drinking trajectories of White, Black and Hispanic men and women from ages 21 to 51. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective, longitudinal study based on nationally representative U.S. data to examine disparities in heavy drinking from early adulthood to middle age.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Dataset

We used data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), which follows a nationally-representative sample of non-institutionalized, civilian (non-military) youth selected using multi-stage probability sampling, including a general population sample and oversamples of Black, Hispanic, and economically-disadvantaged youth. Respondents provided verbal consent prior to each interview after having received an advance letter explaining the study and discussing concerns with interviewers. The NLSY interviewed 12,686 youth aged 14–21 in 1979 and followed them annually through 1994 and biennially since then (ages 47–55 in 2012), with a response rate of 79% in 2012 among those remaining eligible and non-deceased (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2012). The analytic sample for this study includes 4,633 men and 4,835 women who were in the civilian population sample and who provided data on heavy drinking between ages 21 and 51. Data were weighted using the NLSY custom weighting program which uses data from multiple survey years, adjusts for the sampling design, and includes a post-stratification weighting adjustment to ensure representation proportionate to the 1979 Census (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016b). In the current analysis of heavy drinking, weighting takes into account (non)participation in survey waves where drinking data were collected such that those respondents who participated in at least one of these waves were included in the analytic sample.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1 Heavy drinking

Our primary outcome was the frequency of heavy drinking (defined as “6 or more drinks on one occasion”) in the 30 days prior to interview. Because the NLSY response options changed in 2006, we used a four-category variable (never, less than once a week, 1–2 times per week, more than 2 times per week) coded using the weighted empirical means of the midpoints for each response category, and limiting the upper value to be consistent across both sets of response options. Category values were 0, 1.8 (mean of once and 2–3 times per month), 5.1 (mean of 4–5 times and 6–7 times per month), and 11.0 (mean of 8–9 times and 10 or more times per month), and the outcome was treated as a continuous variable. The mean frequency of heavy drinking in 1982 was 1.79 (SD=2.93); in 2012, it was 0.69 (SD=1.98).

Substantial changes in the interview protocol in 1985 resulted in estimates of heavy drinking that were markedly and systematically lower than all other years. We therefore excluded this interview from our analyses. Heavy drinking was measured at 11 time-points, with an average of 8 data points per individual; 98.4% of men and 98.7% of women had data at three or more time-points.

2.2.2 Demographic variables

Race/ethnicity was based on the NLSY assignment of respondents according to self-reported “origin or descent” and self-reported origin with which they most closely identify (for those with multiple racial/ethnic origins). Race/ethnicity was coded at baseline using two mutually-exclusive dummy variables for Black/African American (1,361 men; 1,409 women) and Hispanic/Latino (858 men; 893 women); White/Caucasian was the referent (2,414 men; 2,533 women). We omitted data from all other respondents (719 men and 774 women) due to small and heterogeneous sub-samples for groups such as Native Americans, Asian/Pacific Islanders, and those of other race/ethnicity.

Poverty status was a time-varying variable indicating whether family income in the 12 months prior to each interview was below the federal poverty level. Education was a time-varying variable indicating the highest grade completed, coded in one-year increments from “no formal education” (0) to “8 years of college” (20). Marital status was a time-varying variable coded with two dummy variables for single (never married) and divorced/separated/widowed, using currently married as the referent. Parenthood status was represented with a time-varying dichotomous variable indicating whether the respondent had at least one child (versus none). U.S. nativity status (dichotomous) for Hispanics/Latinos was assessed at baseline.

2.3 Analyses

We used generalized estimating equations (GEE) to model longitudinal heavy drinking trajectories as a function of chronological age, using an exchangeable correlation structure and specifying a cubic curve to describe intra-individual change over time. Models were implemented in Stata (version 13; Stata Corp., 2013). Similar to random effects models, population-average GEE models estimate parameters of a generalized linear model with consideration of within-subject correlation in repeated-measure outcomes (Liang and Zeger, 1986). After verifying there were no cohort differences in the intercepts or slopes, we combined cohorts to take advantage of the accelerated longitudinal design (Miyazaki and Raudenbush, 2000). To reduce instability of predicted values for ages at the extreme ends of the distribution, we limited analyses to ages 21 to 51.

In sex-stratified, unadjusted models we tested racial/ethnic differences in the overall group trajectories (i.e., in intercepts and slopes) using omnibus chi-square tests (henceforth referred to as “tests of racial/ethnic differences”). These tests included a given race indicator, raceXage, raceXage-squared, and raceXage-cubed. To test for significant racial/ethnic differences across the entire age range, we reran models varying the age-centering point, following Muthén and Muthén (2000); age was centered at 21 (in all tables) as well as at 5-year intervals from 25 to 45, and also at 51. Additional chi-square tests simultaneously evaluated the set of racial/ethnic main effects (i.e., the impact on the trajectory intercept) at each age.

Sex-stratified adjusted models included time-varying SES and adult social roles, the latter including marital and parenthood status. Interaction terms and chi-square tests assessed whether SES and social roles were differentially related to heavy drinking across racial/ethnic groups. The final adjusted models were stratified by both sex and race/ethnicity. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using the subsets of (1) respondents who reported heavy drinking on at least one survey (N=3,715 men and 2,629 women), and (2) US-born Hispanics/Latinos (N=582 men and 658 women).

3. RESULTS

3.1 Descriptive Characteristics by Race/ethnicity and Sex

Compared to Whites, Black and Hispanic men and women had significantly less education and greater exposure to poverty. In addition, Blacks and Hispanics were less likely than Whites to be married, and Hispanics and Black women were more likely to have children than their White counterparts.

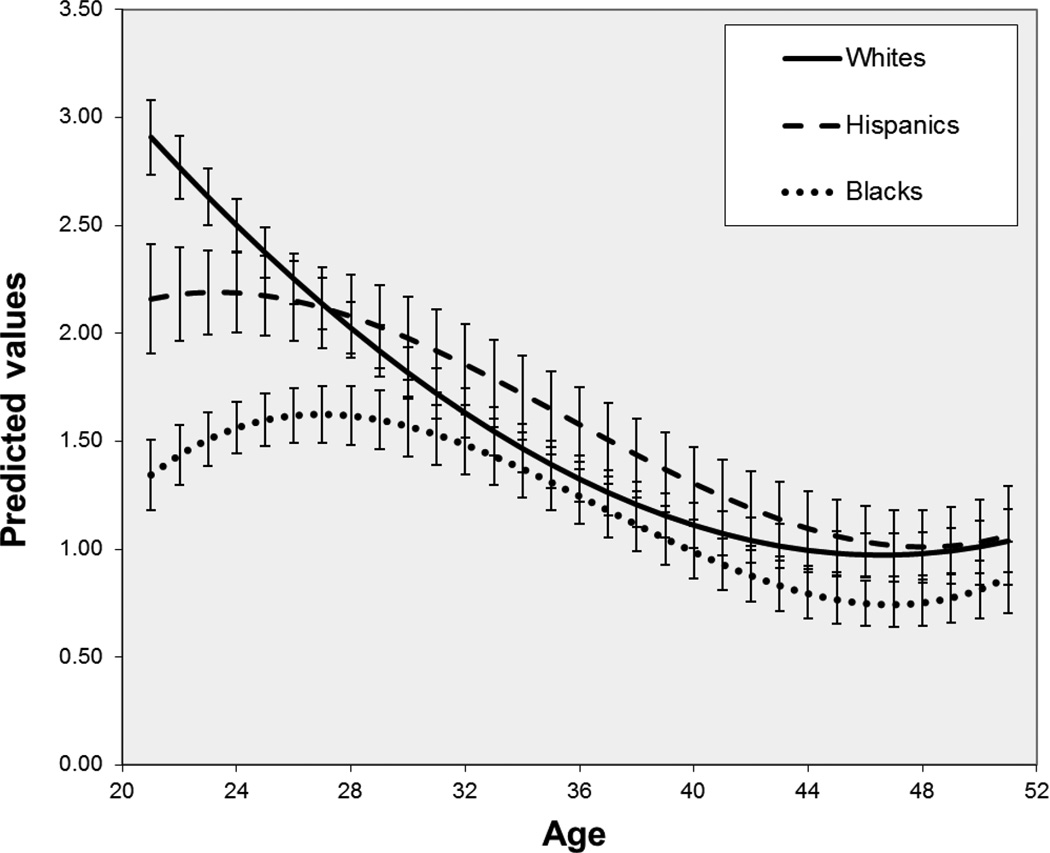

3.2 Trajectory Models for Men

Figure 1 shows the predicted curves for each group of men based on the unadjusted growth curve model (Table 2). There was a steep, rapid decline in heavy drinking frequency for White men, a lower peak and slower decline for Hispanic men, and a delayed increase, lower peak and later decline in heavy drinking frequency for Black men. The confidence intervals indicate that Hispanic and White men’s trajectories become statistically similar and crossover during the late 20s, while Black and White men’s trajectories converge during the early 30s. Tests of racial/ethnic differences in overall trajectories were significant for Black (χ2 (df=4)=172.88, p<001) and Hispanic (χ2 (df=4)=34.79, p<001) men (compared to White men). Specific tests using age re-centered models showed that Black-White differences in heavy drinking were significant only at younger ages (all chi-square p’s < .01 at ages 21, 25 and 30). These age re-centered models confirmed the Hispanic-White crossover and re-convergence shown in Figure 1: Hispanic men’s heavy drinking frequency was lower than White men’s at young ages (significantly at age 21 and marginally at 25), indistinguishable at 30, significantly greater at 35, marginally greater at 40, and again indistinguishable at ages 45 and 51 (coefficients available upon request). At age 51, the main effect of race/ethnicity was no longer significant (χ2 (df=4)=2.85, p>.10) and neither Black nor Hispanic men differed significantly from Whites.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted trajectories of heavy drinking frequency for men, with 95% confidence intervals

Table 2.

Trajectory models of heavy drinking by men in the NLSY79

| Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=4,633) | (N=4,593) | |||

| Coef. (95% CI) | P>|t| | Coef. (95% CI) | P>|t| | |

| Intercept | 2.909 (2.736, 3.082) | <0.01 | 3.797 (3.417, 4.177) | <.01 |

| Black/African American | −1.564 (−1.803, −1.325) | <0.01 | −1.733 (−1.982, −1.483) | <.01 |

| Hispanic/Latino | −0.75 (−1.057, −0.443) | <0.01 | −0.885 (−1.202, −0.567) | <.01 |

| Age | −0.143 (−0.187, −0.099) | <0.01 | −0.072 (−0.121, −0.024) | <.01 |

| Black X Age | 0.246 (0.180, 0.311) | <0.01 | 0.226 (0.154, 0.297) | <.01 |

| Hispanic X Age | 0.172 (0.092, 0.252) | <0.01 | 0.16 (0.075, 0.245) | <.01 |

| Age-squared | 0.002 (−0.001, 0.006) | 0.17 | −0.001 (−0.005, 0.003) | 0.58 |

| Black X Age-squared | −0.013 (−0.018, −0.008) | <0.01 | −0.012 (−0.017, −0.006) | <.01 |

| Hispanic X Age-squared | −0.009 (−0.015, −0.003) | <0.01 | −0.009 (−0.015, −0.002) | 0.01 |

| Age-cubed | 0 (−0.0001, 0.0001) | 0.73 | 0.0001 (−0.00001, 0.0001) | 0.10 |

| Black X Age-cubed | 0.0002 (0.0001, 0.0003) | <0.01 | 0.0002 (0.0001, 0.0003) | <.01 |

| Hispanic X Age-cubed | 0.0001 (0, 0.0003) | 0.03 | 0.0001 (0, 0.0003) | 0.05 |

| Below poverty | −0.113 (−0.262, 0.035) | 0.14 | ||

| Education | −0.112 (−0.138, −0.086) | <.01 | ||

| Single a | 0.69 (0.537, 0.842) | <.01 | ||

| Divorced/separated/widowed a | 0.505 (0.33, 0.68) | <.01 | ||

| 1+ children b | −0.03 (−0.147, 0.087) | 0.62 | ||

Note. Coef, coefficient. CI, confidence interval.

Currently married as reference.

No children as reference.

3.2.1 Adjusted heavy drinking trajectories and race-stratified predictors

After adjusting for poverty, education, and marital and parenthood status, tests of racial/ethnic differences in overall group trajectories (compared to Whites) remained significant for Black men (χ2 (df=4)=210.20, p<.001) and Hispanic men (χ2 (df=4)=32.54, p<.001). The overall adjusted model (Table 2) shows that greater education and being married were protective. Effects of marital status varied by race/ethnicity (χ2 (df=4)=13.28, p<.01; data not shown), indicating that being single (vs. married) was less strongly associated with increasing heavy drinking in Black and Hispanic men compared to White men. Parenthood and poverty status were not significant predictors of heavy drinking for men overall, although race-specific models (Table 4) indicated that parenthood and poverty status were protective for Hispanic men.

Table 4.

Adjusted, stratified models of heavy drinking in the NLSY79

| Coef. (95% CI) | P>|t| | Coef. (95% CI) | P>|t| | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White men (N=2,388) | White women (N=2,510) | |||

| Intercept | 3.758 (3.316, 4.199) | <0.01 | 1.635 (1.347, 1.924) | <0.01 |

| Age | −0.099 (−0.124, −0.074) | <0.01 | −0.039 (−0.053, −0.025) | <0.01 |

| Age-squared | 0.002 (0.0009, 0.002) | <0.01 | 0.001 (0.0003, 0.001) | <0.01 |

| Age-cubed | c | c | ||

| Below poverty | −0.078 (−0.305, 0.149) | 0.50 | 0.010 (−0.130, 0.151) | 0.89 |

| Education | −0.110 (−0.141, −0.078) | <0.01 | −0.059 (−0.079, −0.039) | <0.01 |

| Single a | 0.772 (0.585, 0.960) | <0.01 | 0.509 (0.383, 0.634) | <0.01 |

| Divorced/separated/widoweda | 0.559 (0.336, 0.782) | <0.01 | 0.314 (0.201, 0.428) | <0.01 |

| 1+ children b | −0.020 (−0.162, 0.121) | 0.78 | −0.13 (−0.213, −0.046) | <0.01 |

| Black Men (N=1,349) | Black Women (N=1,402) | |||

| Intercept | 2.416 (1.866, 2.966) | <0.01 | 1.031 (0.722, 1.340) | <0.01 |

| Age | 0.134 (0.077, 0.191) | <0.01 | 0.058 (0.027, 0.090) | <0.01 |

| Age-squared | −0.012 (−0.016, −0.007) | <0.01 | −0.004 (−0.007, −0.002) | <0.01 |

| Age-cubed | 0.0002 (0.0001, 0.0003) | <0.01 | 0.0001 (0.00003, 0.0001) | <0.01 |

| Below poverty | −0.077 (−0.255, 0.101) | 0.40 | 0.206 (0.115, 0.297) | <0.01 |

| Education | −0.117 (−0.156, −0.079) | <0.01 | −0.062 (−0.083, −0.042) | <0.01 |

| Single | 0.359 (0.146, 0.572) | <0.01 | 0.209 (0.122, 0.295) | <0.01 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 0.252 (0.038, 0.466) | 0.02 | 0.087 (0.006, 0.168) | 0.04 |

| 1+ children | 0.011 (−0.176, 0.198) | 0.91 | −0.072 (−0.158, 0.013) | 0.10 |

| Hispanic Men (N=856) | Hispanic Women (N=886) | |||

| Intercept | 3.578 (2.750, 4.407) | <0.01 | 0.859 (0.591, 1.128) | <0.01 |

| Age | 0.074 (0.002, 0.147) | 0.04 | 0.031 (−0.005, 0.067) | 0.09 |

| Age-squared | −0.009 (−0.014, −0.003) | <0.01 | −0.004 (−0.006, −0.001) | 0.01 |

| Age-cubed | 0.0002 (0.00007, 0.0003) | <0.01 | 0.0001 (0.00002, 0.0001) | 0.01 |

| Below poverty | −0.292 (−0.557, −0.026) | 0.03 | −0.113 (−0.241, 0.016) | 0.09 |

| Education | −0.131 (−0.192, −0.07) | <0.01 | −0.024 (−0.043, −0.005) | 0.01 |

| Single | 0.223 (−0.103, 0.550) | 0.18 | 0.260 (0.111, 0.408) | <0.01 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 0.236 (−0.099, 0.572) | 0.17 | 0.261 (0.136, 0.387) | <0.01 |

| 1+ children | −0.33 (−0.607, −0.053) | 0.02 | −0.154 (−0.263, −0.045) | 0.01 |

Note. Coef, coefficient. CI, confidence interval.

Currently married as reference.

No children as reference.

Age term removed because not statistically significant.

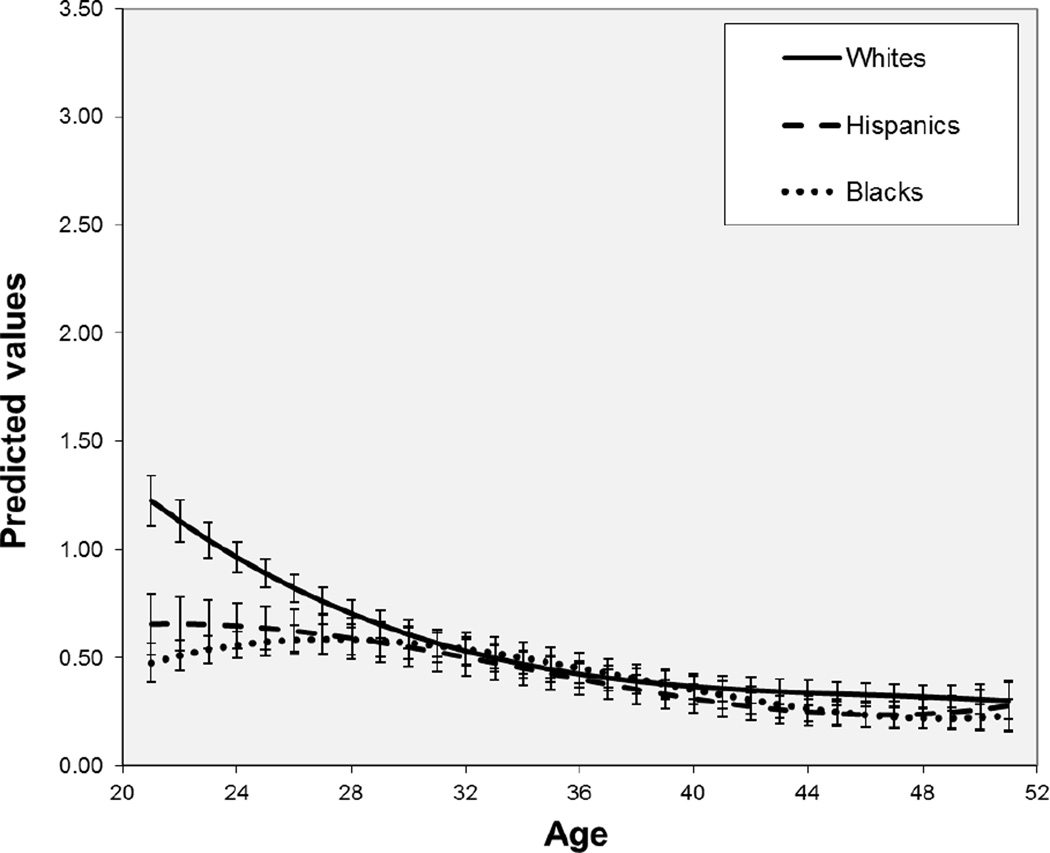

3.3 Trajectory models for Women

Women’s predicted growth curves (Figure 2) showed that White women (similar to White men) had a high peak followed by a steep decline in heavy drinking frequency throughout the 20s. By contrast, Hispanic women had a lower peak and slower decline, and Black women (similar to Black men) had a delayed and lower peak, and slower decline in heavy drinking. Tests of racial/ethnic differences in these overall group trajectories (compared to Whites) were significant for both Black (χ2 (df=4)=104.50, p< 001) and Hispanic women (χ2 (df=4)=37.42, p<.001). Yet age re-centered models showed that these racial/ethnic differences in heavy drinking frequency were significant only at younger ages (specifically 21 and 25, coefficients from re-centered models available upon request). Significant omnibus tests and the model coefficients revealed that at age 21 (χ2 (df=4)=100.80, p<.001) and at age 25 (χ2 (df=4)=48.49, p<001), black and Hispanic women’s heavy drinking was less frequent than that of whites. At older ages (30–51) there were no significant main effects of race/ethnicity (all chi-square p’s > .10).

Figure 2.

Unadjusted trajectories of heavy drinking frequency for women, with 95% confidence intervals

3.3.1 Adjusted drinking trajectories and race-stratified predictors

Tests of racial/ethnic differences remained significant after adjusting for poverty, education and marital and parenthood status (Blacks: χ2 (df=4)=121.43, p<001; Hispanics: χ2 (df=4)=46.11, p<.001). The overall adjusted model in Table 3 shows that, similar to men, greater educational attainment and being married were each associated with less heavy drinking by women, and poverty status was not a significant predictor. Unlike for men, parenthood was a protective factor for women.

Table 3.

Trajectory models of heavy drinking by women in the NLSY79

| Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=4,835) | (N=4,798) | |||

| Coef. (95% CI) | P>|t| | Coef. (95% CI) | P>|t| | |

| Intercept | 1.226 (1.109, 1.344) | <0.01 | 1.631 (1.392, 1.87) | <.01 |

| Black/African American | −0.75 (−0.897, −0.603) | <0.01 | −0.779 (−0.932, −0.626) | <.01 |

| Hispanic/Latino | −0.57 (−0.754, −0.387) | <0.01 | −0.556 (−0.729, −0.384) | <.01 |

| Age | −0.098 (−0.126, −0.07) | <0.01 | −0.045 (−0.073, −0.017) | <.01 |

| Black X Age | 0.136 (0.097, 0.176) | <0.01 | 0.113 (0.071, 0.154) | <.01 |

| Hispanic X Age | 0.101 (0.059, 0.144) | <0.01 | 0.086 (0.041, 0.13) | <.01 |

| Age-squared | 0.004 (0.002, 0.006) | <0.01 | 0.001 (−0.001, 0.003) | 0.30 |

| Black X Age-squared | −0.007 (−0.01, −0.005) | <0.01 | −0.006 (−0.009, −0.003) | <.01 |

| Hispanic X Age-squared | −0.006 (−0.009, −0.003) | <0.01 | −0.005 (−0.008, −0.002) | <.01 |

| Age-cubed | −0.0001 (−0.0001, −0.00001) | 0.02 | −0.00001 (−0.0001, 0.00004) | 0.76 |

| Black X Age-cubed | 0.0001 (0.0001, 0.0002) | <0.01 | 0.0001 (0.00003, 0.0002) | 0.01 |

| Hispanic X Age-cubed | 0.0001 (0.00004, 0.0002) | <0.01 | 0.0001 (0.00002, 0.0002) | 0.01 |

| Below poverty | 0.041 (−0.049, 0.132) | 0.37 | ||

| Education | −0.055 (−0.071, −0.04) | <.01 | ||

| Single a | 0.438 (0.344, 0.531) | <.01 | ||

| Divorced/separated/widoweda | 0.28 (0.195, 0.364) | <.01 | ||

| 1+ children b | −0.129 (−0.194, −0.064) | <.01 | ||

Note. Coef, coefficient. CI, confidence interval.

Currently married as reference.

No children as reference.

The effects of poverty (χ2 (df=4)=16.45, p<.001), being single (χ2 (df=4)=16.36, p<.001) and being divorced, separated or widowed (χ2 (df=4)=12.92, p<.01) varied by race/ethnicity among women. Poverty was related to increasing heavy drinking for Black women, being single rather than married was more strongly associated with increasing heavy drinking in White (vs. both Black and Hispanic) women, and divorce was more strongly associated with increasing heavy drinking in White (vs. Black) women. In the race-specific models (Table 4), parenthood was significantly protective only for White and Hispanic women, and poverty status was a significant risk factor only for Black women.

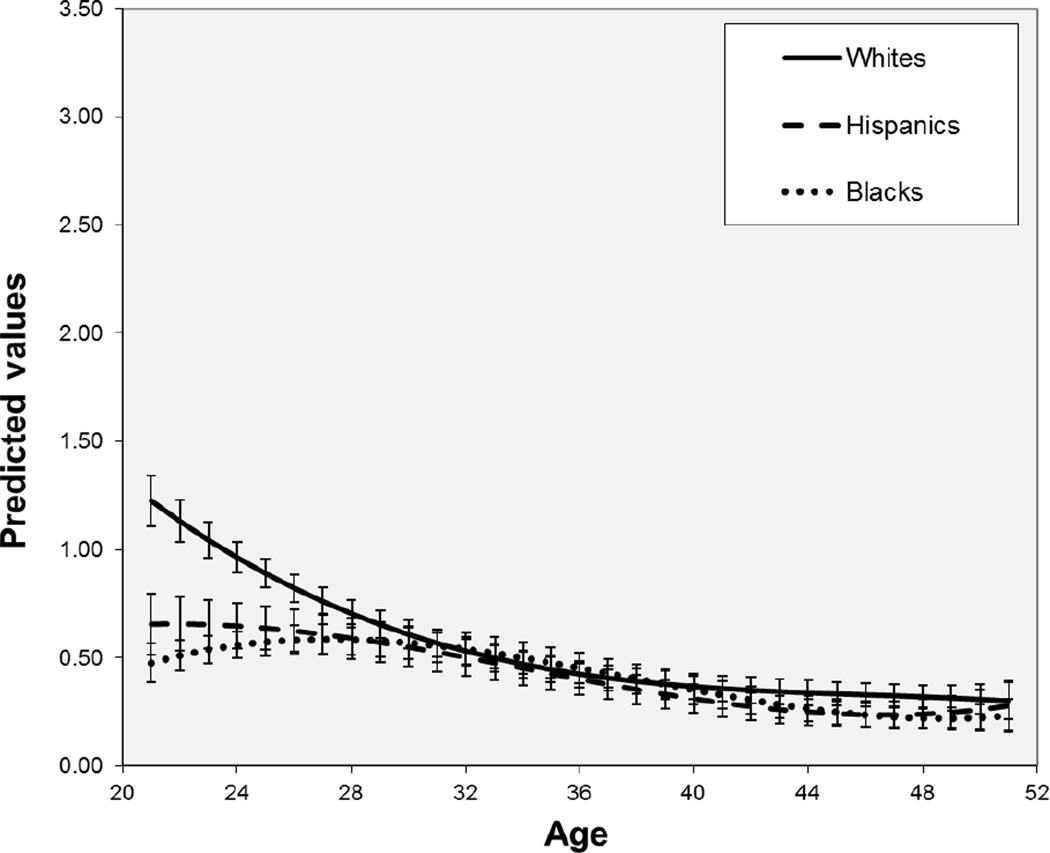

3.4 Sensitivity analyses

Due to racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of abstinence and lifetime heavy drinking, we limited the sample in a sensitivity analysis to drinkers who reported heavy drinking at least once in the study period (omitted observations included 53 men and 123 women who were lifetime abstainers). Findings from unadjusted models were essentially the same as models including the full sample, except the trajectory was shifted upward (i.e., levels of heavy drinking were higher over time). A notable exception was the finding of a significant Black-White crossover in women’s trajectories by age 30 (Figure 3, data available upon request), with Black women drinking heavily more often than White women; this was followed by re-convergence at age 40. Findings from the overall adjusted models were very similar when limited to lifetime heavy drinkers (data available upon request).

Figure 3.

Unadjusted trajectories of heavy drinking frequency for White and Black female lifetime heavy drinkers women, with 95% confidence intervals

In other sensitivity analyses, we ran adjusted models in the sub-sample of US-born Hispanics given prior findings of nativity differences in Hispanic alcohol outcomes (Alegría et al., 2006; Caetano et al., 2009). Results were essentially the same as the models including foreign-born Hispanics, with the exception that the protective effect of poverty reached statistical significance for US-born Hispanic women (data available upon request).

4. DISCUSSION

This general population study entailed a rare examination of the long-term heavy drinking patterns of racial/ethnic groups across 30 years, thereby extending prior alcohol trajectory studies beyond adolescence and young adulthood into midlife. Our findings for this large segment of the adult life course provide additional context for understanding disparities in alcohol use disorders, morbidity, and mortality during and after young adulthood.

Consistent with prior research (Chen and Jacobson, 2012; Maggs and Schulenberg, 2004/2005), we found a steady and steep reduction in White men and women’s heavy drinking frequency throughout the 20s. Unlike other racial/ethnic groups, both Black men and women increased their heavy drinking frequency during their early and mid-20s; this parallels the rising prevalence of African American heavy drinking during this age period (Godette et al., 2006). Compared to Whites, Blacks and Hispanics showed a lower peak frequency but also slower decline in heavy drinking over time. By the end of young adulthood, the heavy drinking of Blacks, Hispanics and Whites converged in both sexes, consistent with reports of Hispanic-White convergence (Evans-Polce et al., 2015 Chen et and Jacobson, 2013; Muthén and Muthén, 2000) and Black-White convergence (Chen and Jacobson, 2013; Muthén and Muthén, 2000; Cooper et al., 2008) described earlier. Future studies are needed with large enough sub-samples to include Native Americans, Asian/Pacific Islanders and multi-racial individuals.

An important new finding from this study concerns the observed crossover in heavy drinking between Hispanic and White men, and Black and White female “ever-heavy” drinkers during the fourth decade of life. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a racial/ethnic crossover in heavy drinking in a U.S. longitudinal sample. This Hispanic-White crossover provides one possible explanation for recently reported age differences in the manifestation of alcoholic liver disease in Hispanic and White patients (a large majority of whom were men), with Hispanics presenting in their early 40s, on average 4 to 10 years earlier than Whites (Levy et al., 2015). The heavy drinking crossover by Hispanic men and Black women is also consistent with previous findings of their greater risk for later AUD onset and persistence into middle age, relative to Whites (Grant et al., 2012).

The absence of a crossover in Black and White men suggests that Black men are not more likely than White men to persist in frequent heavy drinking, contrary to findings from nearly 25 years ago (e.g., Caetano and Kaskutas, 1995). We acknowledge a small increase in Black men’s heavy drinking frequency in the late 40s; it remains to be seen whether extending follow-up into later middle age results in a Black-White crossover. At present, our data suggest that differences in heavy drinking frequency are not a likely cause of Black-White male disparities in alcohol-related problems at this stage of life. Similarly, the convergence in heavy drinking of all three groups by age 51 suggests that other factors may be more important influences on alcohol-related disparities in middle adulthood.

Possible explanations should be examined in future work. Some research suggests that Hispanic men consume greater amounts of alcohol than non-Hispanic men when they do drink (Stinson et al., 2001), and that Black and Hispanic men consume stronger drinks than White men (Kerr et al., 2009a, 2009b). Conceivably, racial/ethnic differences in maximum drink volume and drink strength could compound over the life course, leading to alcohol-related disparities. Another factor could be the large racial/ethnic health inequalities that arise in middle adulthood (Brown et al., 2012; Shuey and Willson, 2008; Yao and Robert, 2008) which, combined with differential access to quality health care and alcohol-related services (Smedley et al., 2002), could contribute to the greater alcohol morbidity and mortality of some minority groups despite convergent heavy drinking in midlife. Other avenues for future inquiry include racial/ethnic differences in nutritional status and biological or genetic vulnerability to alcohol-related health conditions [e.g., alcohol-related pancreatic complications and liver disease (Levy et al., 2015; Yang et al.)], along with possibly differential relationships between heavy drinking and externalizing disorders across groups. Finally, drinking to cope may be another relevant factor (Zapolski et al., 2014; Zemore et al.) given the greater cumulative stress experienced by minorities (Hatch and Dohrenwend, 2007), and has been related to alcohol dependence independent of heavy drinking (Peirce et al., 1994).

Other notable study findings relate to the predictors of heavy drinking for the three racial/ethnic groups. Poverty was a significant risk factor only for Black women, while in U.S.-born Hispanic men and women, poverty was associated with less frequent heavy drinking. Such varied effects may point to qualitatively different experiences of poverty. Blacks are exposed to longer-lasting and more chronic poverty (McKernan et al., 2009; Stevens, 2013), and low-income Black women who are also single parents are often exposed to extreme poverty (Mather, 2010; Shaefer and Edin, 2014). They might therefore face particularly severe and chronic stressors that contribute to their heavy drinking (Mulia et al., 2008). Although this may be surprising considering their lower levels of disposable income, alcohol has become highly affordable over time (Kerr et al., 2013), and studies of the recent recession find that severe economic hardship can motivate heavy drinking despite financial constraints (Mulia et al., 2014b; Zemore et al., 2013). For U.S.-born Hispanics, on the other hand, poverty might be linked with residence in coethnic enclaves, and related social support and mental health benefits (Mair et al., 2010).

Another key finding was that for White men and women, heavy drinking appears to be strongly associated with being young and single, more so than for Black and Hispanic men and women. The significantly steeper decline found in White (vs. Black or Hispanic) heavy drinking during young adulthood thus makes sense, considering Whites’ higher rates of marriage, and that the average age at first marriage used to be in the early 20s (Settersten and Ray, 2010). With regard to our finding that parenthood tends to confer greater protection for women than men, this may reflect women’s greater involvement in parenting (permitting less time available for drinking), and that women who give up heavy drinking during pregnancy and early childrearing might not return to it at older ages (Wilsnack et al., 2009). Finally, greater education was associated with a downward shift in heavy drinking trajectories for all groups, consistent with extensive research showing protective effects of higher education on heavy drinking.

Several study limitations should be noted. First, as discussed, the NLSY measurement of heavy drinking changed in 2006 to incorporate new response categories at the high end of the frequency range. To standardize responses across years, based on extensive preliminary analyses we used a four-category variable that assigned 11 times/month for response categories of at least 3 times/week. This might result in a downward bias for high-frequency heavy drinking assessed as of 2006. Post-hoc descriptive analyses of men and women suggest that all racial/ethnic groups were similarly affected by this measurement issue. Additional sensitivity analyses using a 0–3 scale instead of assigned values for heavy drinking frequency showed a similar pattern of results as reported here. Second, we note that the 6+ drinks/day threshold used in the NLSY79 exceeds current NIAAA guidelines (up to 4 drinks for men and 3 drinks for women in any given day). Our trajectory findings may therefore reflect more extreme heavy drinking, particularly among women. As an important goal is to better understand alcohol-related health disparities, future studies should examine racial/ethnic differences in long-term drinking at levels lower than 6+ but greater than federally recommended daily and weekly limits. Third, several limitations pertain to the available data on race/ethnicity. For instance, while we recognize the cultural heterogeneity within the Hispanic population and sub-ethnic group differences in alcohol outcomes (Alegría et al., 2006; Vaeth et al., 2012), small numbers precluded analysis of Hispanic ethnic subgroups. Similarly, the very small sub-samples of Asians and Native Americans did not allow us to examine whether their trajectories differed from those of Whites; and multiracial individuals were not readily identifiable in these data. A final study limitation is that our findings are only generalizable to those born between 1957 and 1964. It is possible that younger cohorts might show different lifecourse drinking patterns, given recent U.S. demographic shifts that could affect heavy drinking, such as later age of first marriage and longer transitions to other adult roles (Lui et al., 2014; Settersten and Ray, 2010), as well as changing social and legal attitudes towards drinking and its consequences (e.g., Subbaraman and Kerr, 2013). Future studies of disparities across cohorts could shed light on this.

While there appears to be a universal, overall decline in heavy drinking in all three racial/ethnic groups, there are also some important differences in the phenomenon of aging out or “maturing out” of heavy drinking. These include slower declines in Hispanic and Black (vs. White) heavy drinking that result in a trajectory crossover by Hispanic men and Black female lifetime heavy drinkers. Future studies that can identify modifiable factors contributing to this racial/ethnic crossover would be valuable in advancing efforts to reduce alcohol-related disparities. At present, study results suggest that policy and programmatic interventions to mitigate poverty also may decrease heavy drinking by Black women. Poverty reductions may be facilitated, in part, by increasing access to quality education and educational attainment, which should decrease heavy drinking in all other groups examined here. Recent work by Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2010) shows that each additional year of schooling is associated with less frequent heavy drinking, particularly among those with at least 11 years of education, and that this and other health benefits of higher education were partly due to greater economic resources. While these findings reinforce the notion of education as a crucial pathway to improved health and well-being, we should bear in mind racial/ethnic differences in the economic returns on education (Williams, 1996, 1999). Future studies should consider possible differences in the health benefits of education and across different life stages, as a recent report finds that college drop-out may have greater adverse effects on subsequent heavy drinking in Black young adults than Whites (Chen and Jacobson, 2013). Research of this kind can help to ensure progress towards improving population health and reducing health inequities.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the NLSY79 Sample, 1979 – 2012

| White | Black / African American |

Hispanic / Latino |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | N=2,388 | N=1,349 | N=856 |

| Mean Age | 32.7 (0.039) | 32.9 (0.046)** | 32.8 (0.067) |

| Education (mean years of education) | 13.4 (0.057) | 12.5 (0.061)*** | 12.1 (0.112)*** |

| Below Poverty | 7% (0.003) | 23.2% (0.008)*** | 16.4% (0.008)*** |

| Single | 32.6% (0.008) | 52.1% (0.012)*** | 36.4% (0.015) |

| Married | 55.4% (0.008) | 32.9% (0.010)*** | 48.8% (0.014)*** |

| Divorced/ Separated/ Widowed | 12.0% (0.005) | 15.0% (0.007)*** | 14.7% (0.009)** |

| 1+ Children | 37.6% (0.008) | 30.2% (0.010)*** | 43.7% (0.014)*** |

| Non-Heavy Drinking | 59.0% (0.008) | 71.2% (0.008)*** | 59.5% (0.013) |

| Women | N=2,510 | N=1,402 | N=886 |

| Mean Age | 32.9 (0.035) | 33.2 (0.037)*** | 33.0 (0.061) |

| Education (mean years of education) | 13.4 (0.054) | 12.9 (0.057)*** | 12.2 (0.110)*** |

| Below Poverty | 9.7% (0.004) | 33.4% (0.009)*** | 23.7% (0.011)*** |

| Single | 21.4% (0.007) | 44.2% (0.012)*** | 23.4% (0.013) |

| Married | 62.9% (0.007) | 31.5% (0.009)*** | 54.7% (0.013)*** |

| Divorced/ Separated/ Widowed | 15.7% (0.006) | 24.3% (0.009)*** | 21.9% (0.011)*** |

| 1+ Children | 61.9% (0.008) | 74.1% (0.010)*** | 74.5% (0.014)*** |

| Non-Heavy Drinking | 80.8% (0.006) | 87.5% (0.006)*** | 85.1% (0.009)*** |

Note. Means and percentages shown with standard errors in parentheses. All comparisons are to whites.

p<.001,

p<.01,

p<.05.

Highlights.

Whites’ heavy drinking frequency declined steeply in the 20s

Blacks’ and Hispanics’ less frequent heavy drinking declined more slowly

Minority-white crossovers occurred for some groups in the 30s

By age 51 there were no significant racial/ethnic differences in either gender

These crossovers might help to explain racial disparities in health at midlife

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank two anonymous reviewers and the associate editor for their helpful comments and suggestions on the manuscript, and Dr. Tammy Tam for elucidating the NLSY data structure and developing early analysis plans which inform this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Disclosures

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health (R01AA022668, N. Mulia PI and P50AA005595, W. Kerr PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributors

NM and KKJ conceptualized the study; KKJ led the analysis with support from JW, JB, and EW; EW was responsible for data management; all authors were involved in interpreting results; NM and KKJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to revisions prior to submission.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared.

REFERENCES

- Akins S, Lanfear C, Cline S, Mosher C. Patterns and correlates of adult American Indian substance use. J. Drug Issues. 2013;43:497–516. [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Canino GJ, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Nativity and DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Puerto Ricans, Cuban Americans, and Non-Latino Whites in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2006;67:56–65. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Manson SM, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Novins DK, Mitchell CM. Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders and attendant help-seeking in 2 American Indian reservation populations. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:99–108. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TH, O’Rand AM, Adkins DE. Race-ethnicity and health trajectories: tests of three hypotheses across multiple groups and health outcomes. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2012;53:359–377. doi: 10.1177/0022146512455333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1979: Retention and reasons for noninterview. Washington, DC: 2012. [Accessed: 2016-04-19]. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6gtcIW5tR] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1979. Washington, DC: 2016a. [Accessed: 2016-04-20]. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6gum2rjbv] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Longitudinal Surveys: Custom weighting program documentation. Washington, DC: 2016b. [Accessed: 2016-04-20]. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6guiInSY0] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL. Trends in alcohol-related problems among whites, blacks, and Hispanics: 1984–1995. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1998;22:534–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Kaskutas LA. Changes in drinking patterns among whites, blacks and Hispanics: 1984–1992. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1995;56:558–565. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Rodriguez LA. The Hispanic Americans Baseline Alcohol Survey (HABLAS): the association between birthplace, acculturation and alcohol abuse and dependence across Hispanic national groups. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Feingold A, Kim HK, Yoerger K, Washburn IJ. Heterogeneity in growth and desistance of alcohol use for men in their 20s: prediction from early risk factors and association with treatment. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2013;37:E347–E355. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casswell S, Pledger M, Pratap S. Trajectories of drinking from 18 to 26 years: identification and prediction. Addiction. 2002;97:1427–1437. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K, Caetano R. Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Res. Health. 2010;33:152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: gender and racial/ethnic differences. J. Adolesc. Health. 2012;50:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Jacobson KC. Longitudinal relationships between college education and patterns of heavy drinking: a comparison between Caucasian and African-Americans. J. Adolesc. Health. 2013;53:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Krull JL, Agocha VB, Flanagan ME, Orcutt HK, Grabe S, Dermen KH, Jackson M. Motivational pathways to alcohol use and abuse among black and white adolescents. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2008;117:485–501. doi: 10.1037/a0012592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A. Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. J. Health Econ. 2010;29:1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Grant BF. Changes in alcohol consumption: United States, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Polce RJ, Vasilenko SA, Lanza ST. Changes in gender and racial/ethnic disparities in rates of cigarette use, regular heavy episodic drinking, and marijuana use: ages 14 to 32. Addict. Behav. 2015;41:218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godette DC, Headen S, Ford CL. Windows of opportunity: fundamental concepts for understanding alcohol-related disparities experienced by young blacks in the United States. Prev. Sci. 2006;7:377–387. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B, Hasin DS. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JD, Vergés A, Jackson KM, Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Bucholz KK. Age and ethnic differences in the onset, persistence and recurrence of alcohol use disorder. Addiction. 2012;107:756–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene KM, Eitle TM, Eitle D. Adult social roles and alcohol use among American Indians. Addict. Behav. 2014;39:1357–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK. Health disparities in alcohol-related disorders, problems, and treatment use by minorities. FrontLines: Linking Alcohol Services Research and Practice. 2001 Jun;3:7. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Ye Y, Bond J, Midanik LT. Alcohol Consumption And Related Problems Among Black, White, And Hispanic Groups In The United States: The 2000 NAS; 46th International Council on Alcohol and Addictions; October 19–24; Toronto, Canada. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch SL, Dohrenwend BP. Distrubution of traumatic and other stressful life events by race/ethnicity, gender, SES and age: a review of the research. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007;40:313–332. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9134-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd D. Predicting drinking problems among black and white men: results from a national survey. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1994;55:61–71. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton J. Race and Ethnicity in Fatal Motor Vehicle Traffic Crashes 1999–2004 (DOT HS 809 956) Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic and Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation; 2006. [Accessed: 2015-04-14]. p. 22. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6XmxLVceI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ. Similarities and differences of longitudinal phenotypes across alternate indices of alcohol involvement: a methodologic comparison of trajectory approaches. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2005;19:339–351. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlamangla A, Zhou K, Reuben D, Greendale G, Moore A. Longitudinal trajectories of heavy drinking in adults in the United States of America. Addiction. 2006;101:91–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Patterson D, Greenfield TK. Differences in the measured alcohol content of drinks between black, white and Hispanic men and women in a US national sample. Addiction. 2009a;104:1503–1511. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Patterson D, Greenfield TK, Jones AS, McGeary KA, Terza JV, Ruhm CJ. U.S. alcohol affordability and real tax rates, 1950- 2011. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013;44:459–464. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Patterson D, Koenen MA, Greenfield TK. Large drinks are no mistake: glass size, not shape, affects alcoholic beverage drink pours. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009b;28:360–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Vo T, Wall MM, Caetano R, Suglia S, Martins SS, Galea S, Hasin D. Racial/ethnic differences in use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana: is there a cross-over from adolescence to adulthood? Soc. Sci. Med. 2015;124:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy RE, Catana AM, Durbin-Johnson B, Halsted CH, Medici V. Ethnic differences in presentation and severity of alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2015;39:566–574. doi: 10.1111/acer.12660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lui CK, Chung PJ, Wallace SP, Aneshensel CS. Social status attainment during the transition to adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014;43:1134–1150. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0030-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Schulenberg JE. Trajectories of alcohol use during the transition to adulthood. Alcohol Res. Health. 2004/2005;28:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Mair C, Diez Roux AV, Osypuk TL, Rapp SR, Seeman T, Watson KE. Is neighborhood racial/ethnic composition associated with depressive symptoms? The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010;71:541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M. U.S. children in single-mother families. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau; 2010. [Accessed: 2016-02-24]. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6fXdJ2YkJ] [Google Scholar]

- McKernan S-M, Ratcliffe C, Cellini SR. Transitioning in and out of poverty. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2009. [Accessed: 2016-04-22]. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6gxoQt9Zr] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki Y, Raudenbush SW. Tests for linkage of multiple cohorts in an accelerated longitudinal design. Psychol. Methods. 2000;5:44–63. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.5.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Schmidt L, Bond J, Jacobs L, Korcha R. Stress, social support and problem drinking among women in poverty. Addiction. 2008;103:1283–1293. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Tam T, Bond J, Zemore SE, Li L. Racial/ethnic disparities in lifecourse heavy drinking from adolescence to mid-life. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2016.1275911. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Tam T, Schmidt LA. Disparities in the use and quality of alcohol treatment services and some proposed solutions. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014a;65:626–633. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Zemore SE, Murphy R, Liu H, Catalano R. Economic loss and alcohol consumption and problems during the 2008 to 2009 U.S. recession. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2014b;38:1026–1034. doi: 10.1111/acer.12301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. The development of heavy drinking and alcohol-related problems from ages 18 to 37 in a U.S. national sample. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2000;61:290–300. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Forecast for the Future: Strategic plan to address health disparities. Bethesda, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Updated 2005 Edition, revised October 2015 (NIH Publication No. 07-3769) Rockville, MD: 2005. [Accessed: 2016-08-12]. Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician’s guide. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6jiIsTNiY] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce RS, Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Relationship of financial strain and psychosocial resources to alcohol use and abuse: the mediating role of negative affect and drinking motives. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1994;35:291–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polednak AP. Temporal trend in the U.S. black-white disparity in mortality rates from selected alcohol-related chronic diseases. J. Ethn. Subst. Abuse. 2008;7:154–164. doi: 10.1080/15332640802055558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA, Jr, Ray B. What’s going on with young people today? The long and twisting path to adulthood. Future Child. 2010;20:19–41. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaefer HL, Edin K. The rise of extreme poverty in the United States [Accessed: 2016-02-24. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6fXcIWx98] Pathways. :28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Jackson KM, Steinley D. Alcohol use trajectories and the ubiquitous cat’s cradle: cause for concern? J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2011;120:322–335. doi: 10.1037/a0021813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuey KM, Willson AE. Cumulative disadvantage and black-white disparities in life-course health trajectories. Res. Aging. 2008;30:200–225. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial And Ethnic Disparities In Health Care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens AH. Transitions Into And Out Of Poverty In The United States. Policy Brief, UC Davis Newsletter 1. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Dufour MC, Steffens RA, DeBakey SF. Alcohol-related mortality in the United States, 1979–1989. Alcohol Health Res. World. 1993;17:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dufour MC. The critical dimension of ethnicity in liver cirrhosis mortality statistics. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2001;25:1181–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraman MS, Kerr WC. State panel estimates of the effects of the minimum legal drinking age on alcohol consumption, 1950–2002. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2013;37:E291–E296. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01929.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaeth PA, Caetano R, Rodriguez LA. The Hispanic Americans Baseline Alcohol Survey (HABLAS): the association between acculturation, birthplace and alcohol consumption across Hispanic national groups. Addict. Behav. 2012;37:1029–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner LA, White HR, Johnson V. Alcohol initiation experiences and family history of alcoholism as predictors of problem-drinking trajectories. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:56–65. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Jackson K. Social and psychological influences on emerging adult drinking behavior. Alcohol Res. Health. 2004–2005;28:182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status: measurement and methodological issues. Int. J. Health Serv. 1996;26:483–505. doi: 10.2190/U9QT-7B7Y-HQ15-JT14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status, and health. The added effects of racism and discrimination. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999;896:173–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz-Holm ND, Gmel G. Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction. 2009;104:1487–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang AL, Vadhavkar S, Singh G, Omary B. Epidemiology of alcohol-related liver and pancreatic disease in the United States. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008;168:649–656. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L, Robert SA. The contributions of race, individual socioeconomic status, and neighborhood socioeconomic contest on the self-rated health trajectories and mortality of older adults. Res. Aging. 2008;30:251–273. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y-H, Yi H-y. Liver Cirrhosis Mortality in the United States, 1970–2004 [Surveillance Report #79] Arlington, VA: National Institue on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y-H, Yi H-Y, Thompson PC. Alcohol-related and viral hepatitis C-related cirrhosis mortality among Hispanic subgroups in the United States, 2000–2004. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011;35:240–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Pedersen SL, McCarthy DM, Smith GT. Less drinking, yet more problems: understanding African American drinking and related problems. Psychol. Bull. 2014;140:188–223. doi: 10.1037/a0032113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE, Mulia N, Jones-Webb RJ, Lui H, Schmidt L. The 2008–2009 recession and alcohol outcomes: differential exposure and vulnerability for black and Latino populations. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74:9–20. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE, Ye Y, Mulia N, Martinez P, Jones-Webb R, Karriker-Jaffe KJ. Poor, persecuted, young, and alone: toward explaining the elevated risk of alcohol problems among black and Latino men who drink. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;163:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]