Abstract

As the market and related industry for wearable electronics dramatically expands, there are continuous and strong demands for flexible and stretchable devices to be seamlessly integrated with soft and curvilinear human skin or clothes. However, the mechanical mismatch between the rigid conventional electronics and the soft human body causes many problems. Therefore, various prospective nanomaterials that possess a much lower flexural rigidity than their bulk counterparts have rapidly established themselves as promising electronic materials replacing rigid silicon and/or compound semiconductors in next-generation wearable devices. Many hybrid structures of multiple nanomaterials have been also developed to pursue both high performance and multifunctionality. Here, we provide an overview of state-of-the-art wearable devices based on one- or two-dimensional nanomaterials (e.g., carbon nanotubes, graphene, single-crystal silicon and oxide nanomembranes, organic nanomaterials and their hybrids) in combination with zero-dimensional functional nanomaterials (e.g., metal/oxide nanoparticles and quantum dots). Starting from an introduction of materials strategies, we describe device designs and the roles of individual ones in integrated systems. Detailed application examples of wearable sensors/actuators, memories, energy devices, and displays are also presented.

Keywords: Silicon nanomembrane, Functional nanomaterials, Flexible electronics, Stretchable electronics, Wearable electronics

Introduction

In the rapid technology development of low-power silicon electronics, light-emitting diodes (LEDs) fabricated on unconventionally shaped substrates, high-capacity lithium-ion batteries, and various wearable electronic devices such as smart glasses, watches, and lenses have been unveiled both in academic journals and on the market. In spite of their superb performance, wearable form factors, and compact sizes, challenges remain mainly owing to their large thickness and mechanical rigidity, which result in a mechanical mismatch between the device and the skin, and thereby discomfort, a low signal-to-noise ratio, and measurement errors [1]. In this regard, achieving mechanical deformability of the wearable electronic/optoelectronic devices while maintaining high performances has been a major research goal [2–6].

One promising strategy is to replace the rigid electronic materials (e.g., silicon wafer) with flexible nanomaterials (e.g., silicon nanomembrane (SiNM) [7–11], carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [12–14], graphene (GP) [1, 15, 16], and organic nanomaterials [17, 18]). The electronic properties of the SiNM (down to tens of nanometers) remain the same as the bulk silicon wafer [19], but its bendability dramatically increases owing to the reduced thickness [5]. SiNM-based devices outperform their competitors including low-temperature polycrystalline silicon (LTPS) and organic devices by virtue of their high electron mobility [20]. However, SiNM based device might have issues in the high cost and complicated fabrication processes. Meanwhile, carbon nanomaterials (e.g., CNTs and GP) [21, 22] have been getting attentions as next-generation semiconducting nanomaterials. The mobility of single-walled CNTs (SWNTs) and exfoliated GP have been reported up to 100,000 [21] and 230,000 cm2 V−1 s−1 [22], respectively, which are higher than that of single-crystal silicon. Their ultrathin thickness enables them to be seamlessly integrated in wearable devices while achieving the transparency [23–25]. The mass production, device performance, and fabrication processes of these carbon nanomaterials, however, have many remaining challenges for commercial device applications [26]. Organic nanomaterials such as organic nanowires/nanofibers also have recently utilized as electric materials for fabricating complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) circuits [27] and wearable power generators [28, 29]. Intrinsic deformability of organic nanomaterials, solution processability, and low cost make them promising for wearable devices [27]. However, their low electrical performances should be resolved for its widespread applications [17].

Another approach to achieve both high performance and multifunctionality is to utilize hybrids of nanomaterials [30–36]. Functional hybrid nanomaterials often exhibit substantially different physical, mechanical, magnetic, chemical, and optical properties compared to their individual and/or bulk counterparts [37–40]. By integrating different functional nanomaterials, the performance of wearable devices can be dramatically improved and/or diversified [1, 7, 41–46]. For the realization of this goal, the type, size, thickness, and concentration of the nanomaterials should be carefully designed [46]. In the following, we summarize recently reported wearable sensors/actuators [7, 13, 47], memories [41, 48], energy storage devices [49], and displays [50, 51] that exploit various nanomaterials [7, 44, 46, 52, 53] and their hybrids (Fig. 1). We also describe the roles of each nanomaterial in specific devices, improved device functions, their system integrations, and provide brief perspectives on future research directions.

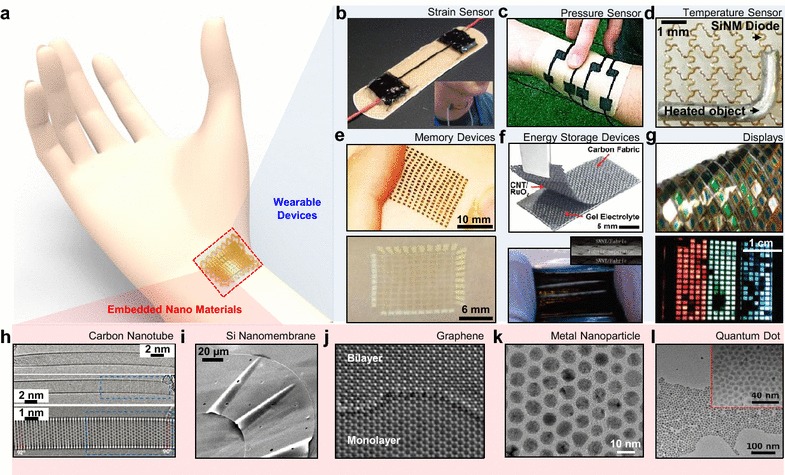

Fig. 1.

Overview of wearable devices with integrated nanomaterials. a Schematic of a wearable device mounted on human skin. b–g Optical images of representative wearable devices consisting of functional nanomaterials: b strain sensor, c pressure sensor, d temperature sensor, e memory arrays, f energy storage devices; and g displays. (b–g Reproduced with permission from b Ref. [13], © 2011, Nature Publishing Group; c Ref. [47], © 2014, WILEY–VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim; d Ref. [7], © 2014, Nature Publishing Group; e Refs. [48] and [41], © 2015, American Chemical Society and © 2014, Nature Publishing Group; f Ref. [45] and [49], © 2014, WILEY–VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim and © 2010, American Chemical Society; g Refs. [51] and [50], © 2009, Nature Publishing Group and © 2013, Nature Publishing Group). h–l Transmission/scanning electron microscopy (TEM/SEM) images of representative functional nanomaterials integrated into wearable devices: h CNTs, i an SiNM, j GP, k metal nanoparticles, and l quantum dots. (h–l Reproduced with permission from h Ref. [52], © 2011, Nature Publishing Group; i Ref. [7], © 2014, Nature Publishing Group; j Ref. [53], © 2011, Nature Publishing Group; k Ref. [46], © 2015, WILEY–VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim; l Ref. [44], © 2015, Nature Publishing Group)

Review

Wearable sensors/actuators

Wearable sensors/actuators have recently attracted considerable interest because of their mobile healthcare [54] and virtual reality applications [55]. Sensors/actuators worn on the body, in particular, have drawn attention for the continuous and accurate monitoring of physiological (e.g., motion [1, 47] and temperature [56, 57]) and electrophysiological (e.g., electrocardiograms [58, 59] and electromyograms [60, 61]) signals and appropriate instant feedback on them [1], which are important for point-of-care medical diagnostics and therapy. This section describes representative wearable sensors/actuators based on functional nanomaterials and their application examples in healthcare and human–machine interfaces.

SiNM-based sensors

Deformability, which is one of the key characteristics of wearable electronics, can be achieved by making inorganic materials (i.e., silicon) as thin as possible, down to the nanometer scale (i.e., nanomembrane) [5]. SiNM can be fabricated through several processes. One easy fabrication method is to remove the buried oxide of a silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafer and pick the top part up or to etch the bottom silicon of the SOI wafer and use the remaining top part [7]. The obtained SiNM can be located in the desired position of the designed layout by using previously reported transfer printing techniques. SiNM maintains the high carrier mobility [20] and intrinsic piezoresistivity [7] of the bulk monocrystalline silicon, while having a high flexibility, which enables diverse wearable electronics applications.

For instance, multiplexing through SiNM transistors integrated into the flexible high-density electrode array achieves the real-time analysis of electrophysiological signals over a large area of the brain [10] and heart [62] surface. SiNM strain gauges integrated onto polymeric substrates are applied as wearable motion sensors thanks to their high piezoresistive sensitivity [7, 8]. Figure 2a shows images of a SiNM strain gauge array integrated with a finger tube that conforms to the thumb. The bending motion of the thumb applies a tensile stress to the SiNM strain gauges, and their resistance increases accordingly without any hysteresis (Fig. 2b). Multiplexing by SiNM p–i–n junction diodes is also advantageous for constructing a wearable high-spatial-resolution temperature sensor array. Figure 2c depicts an 8 × 8 p–i–n junction diode array located on a heated Cu element (left) and its measured temperature distribution (right). The rectifying characteristics of silicon diodes enable each cell to be individually addressable with the minimum number of wires and crosstalk, achieving a high spatial resolution. The ultrathin dimensions of the sensor array facilitate not only conformal contacts with the target surface but also a fast response time by virtue of its extremely low thermal mass.

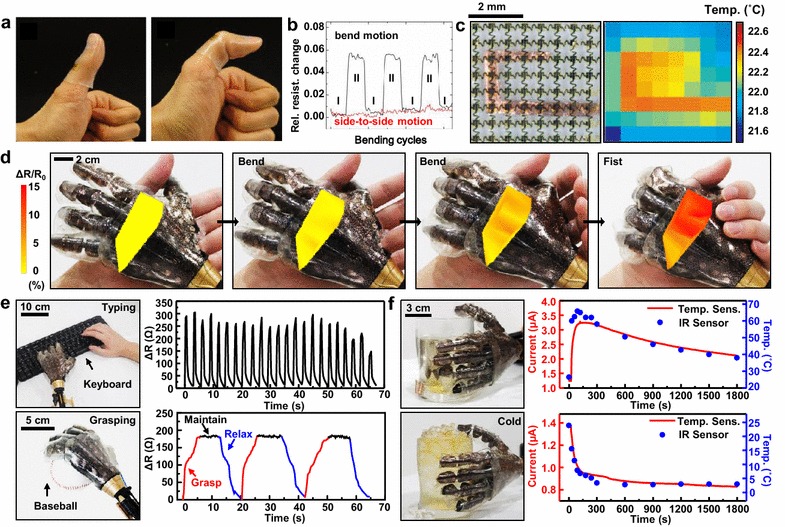

Fig. 2.

SiNM-based wearable sensors. a SiNM-based strain gauge array on a polymer-based finger tube mounted on a relaxed (left) and bent thumb (right). b Relative change in the resistance of the SiNM strain gauge according to the bending (black) and side-to-side (red) motion of the thumb. (a, b Reproduced with permission from Ref. [8], © 2012, IOP Science). c SiNM-diode-based wearable temperature sensor located on a heated metal element (left) and the measured temperature distribution (right). d SiNM strain gauge array integrated onto prosthetic skin, which measures the strain distribution when during handshaking. (c, d Reproduced with permission from Ref. [57], © 2013, Nature Publishing Group). e SiNM pressure sensor integrated onto prosthetic skin, which measures the applied pressure when the wearer is typing with a keyboard (top right) and grasping a ball (bottom left), and the corresponding measured change in the resistance of the SiNM pressure sensor (right). f SiNM temperature sensor integrated onto prosthetic skin, which measures the changes in the temperature of hot (top) and cold (bottom) glass cups. (d–f Reproduced with permission from Ref. [7], © 2014, Nature Publishing Group)

By combining the SiNM strain gauge, pressure sensor, and temperature sensor array in a single platform, a skin-like device conformally mounted onto a prosthetic arm is demonstrated. The SiNM strain gauge array monitors the change in the strain distribution according to the clenching motion of the prosthetic hand (Fig. 2d). Similarly, the SiNM pressure sensor measures the applied pressure when typing with a keyboard (Fig. 2e, top) and grasping a baseball (Fig. 2e, bottom). The SiNM temperature sensor mounted on the prosthetic skin distinguishes different surface temperatures (Fig. 2f). Although these SiNM sensors exhibit a high potential for various wearable sensing applications, there are cost issues to be addressed for the development of commercial products.

CNT-based wearable sensors

The macroscopic form of CNTs in most devices is either their aligned arrays or random networks. Hata et al. [12] developed a synthesis method for ultra-long vertically aligned CNTs using the water-assisted chemical vapor deposition (CVD) process. The vertically aligned CNTs could be selectively grown on a patterned catalyst layer and transferred onto a stretchable substrate for device applications such as a strain sensor (Fig. 3a) [13]. In this strain measurement, the CNT film deforms as the substrate is stretched and its resistance increases. This relative change in the resistance according to the applied strain can be used for human-motion detection. When the sensor is attached to a human knee, the change in the resistance exhibits variations corresponding to the wearer’s motion (Fig. 3b). Although vertical CNTs are densely aligned similar to a forest and therefore have a dark color, randomly oriented CNT networks are relatively transparent, particularly at reduced CNT concentrations [14]. Figure 3c shows a schematic of a transparent patch-type strain sensor using random-network CNTs integrated with a conducting polymer. By virtue of its optical transparency (62 %), it was inconspicuously patched onto a human face and successfully distinguished facial motions (Fig. 3d–f).

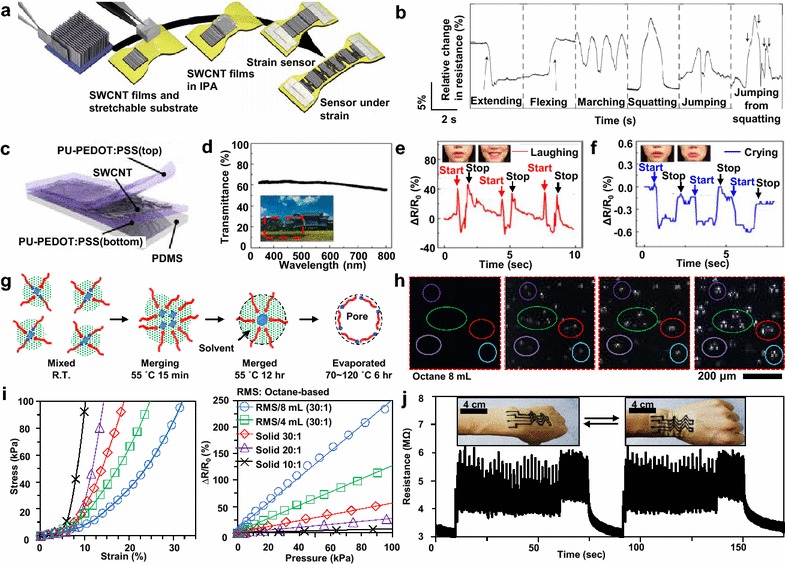

Fig. 3.

CNT-based wearable sensors. a Schematic of the fabrication process of the aligned CNT strain sensor. b Relative change in the resistance of the strain sensor patched onto the knee depending on his/her specific movements. (a–b Reproduced with permission from Ref. [13], © 2011, Nature Publishing Group). c Schematic exploded view of the transparent patchable strain gauge. d Transmittance of the strain gauge depending on the wavelength and a photograph showing the device placed on a picture (inset). e, f Relative change in the resistance of the strain sensor patched onto the face while e he/she is laughing and f crying. (c–f Reproduced with permission from Ref. [14], © 2015, American Chemical Society). g Schematics of the pore generation process according to the heat treatment conditions. h Successive images of the ECR under heat treatment, showing the gradually forming pores inside. i Stress–strain curves of various types of ECRs, obtained by deforming them and measuring the strain and applied stress (left), and the relative change in the resistance of the ECRs with respect to the applied pressure (right). j Change in the resistance of the wearable porous ECRs according to the repetitive bending and relaxing motions of the wrist. (g–j Reproduced with permission from Ref. [47], © 2014, WILEY–VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim)

CNTs are also excellent nanoscale filler materials owing to their small size with good dispersion and exceptional electrical and physical properties [63, 64]. In this regard, electrically conductive rubber (ECR), which is a composite of CNTs and elastomeric polymers, is prepared and used for a wearable mechanical sensor [47]. To enhance the sensitivity, nanopores and micropores are introduced into the ECR, thereby increasing its piezoresistivity and maximizing the locally induced strain when deformed [47]. Figure 3g shows a representative method for introducing pores with a uniform size and distribution in the ECR. The key idea of this method is to use a reverse micelle solution (RMS) comprising an emulsifier, deionized (DI) water, and an organic solvent. In accordance with careful sequential heat treatments, the migration and merging of the reverse micelles and subsequent pore generations occur (Fig. 3h). A larger porosity and lower elastic modulus are achieved if a larger amount of solvent is included in the RMS, thereby resulting in a higher pressure sensitivity (Fig. 3i). An ECR-based strain gauge fabricated on a medical bandage by using ink-jet printing forms a conformal contact with the human wrist and successfully monitors wrist motions. Although sensors based on CNT networks/composites are relatively cheap, especially those that are solution-processed, and mechanically compatible when worn on the human body, several issues such as a slow response time, a large area uniformity, and the hysteresis and drift of signals still need to be solved.

Wearable sensors/actuators based on nanomaterial hybrids

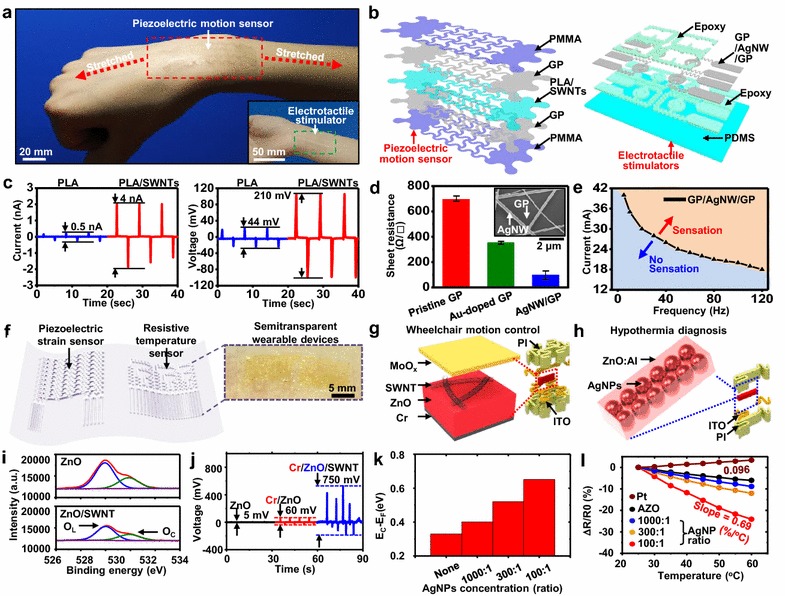

In several cases, electronic materials having a relatively poor performance are incorporated owing to the limited processing temperature and chemical/mechanical resistance of plastic substrates [65]. Appropriately chosen functional nanomaterials compensate for these limitations and improve the device performance [46, 66]. Figure 4a shows a transparent piezoelectric motion sensor and electrotactile stimulator (inset) conformally laminated onto the human skin. The piezoelectric motion sensor consists of GP layers as the transparent electrodes, polylactic acid (PLA) as the piezoelectric material, and SWNTs as the piezoelectric performance enhancer (Fig. 4b, left). Moreover, the electrotactile stimulator utilizes doped GP layers as transparent electrodes and silver nanowires (AgNWs) as a conductivity enhancer (Fig. 4b, right). The strain-induced charge separation in PLA is the main mechanism for piezoelectric energy generation. The local increase in the modulus by the CNTs increases the locally induced strain inside PLA under deformation, which maximizes charge generation (Fig. 4c). Figure 4d shows the conductivity enhancement by AgNWs sandwiched between GP layers. The enhanced conductivity of the GP/AgNWs/GP hybrid contributes to effective electrotactile stimulation (Fig. 4e).

Fig. 4.

Wearable devices with performance-enhancing nanomaterials. a Photographs showing a transparent wearable motion sensor based on a GP heterostructure and the wearable electrotactile stimulator mounted onto human skin. b Schematic exploded structure of the transparent wearable motion sensor (left) and electrotactile stimulator (right). c Output current (left) and voltage (right) of the wearable motion sensor consisting of PLA (blue) and PLA/SWNTs (red) according to the bending and relaxing motions of the device. d Sheet resistance of pristine GP (red), GP doped with an AuCl3 solution (green), an AgNW/GP composite (blue), and its SEM image (inset). e Minimum required current for the wearer to sense stimulation with respect to the stimulation frequency. (a–e Reproduced with permission from Ref. [1], © 2015, WILEY–VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim). f Schematics of a semitransparent piezoelectric strain sensor, resistive sensor, and photograph of their applied form on skin (inset). g, h Schematics of g, the wearable piezoelectric strain sensor and h resistive temperature sensor. i X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy results obtained from a ZnO nanomembrane (top) and ZnO/SWNT composite (bottom). j Output voltage of the piezoelectric strain sensor consisting of ZnO (black), Cr/ZnO (red), and Cr/ZnO/SWNT (blue) for repetitive bending and relaxing of the sensor. k EC − EF of the AZO nanomembrane with different concentrations of AgNPs. l Relative change in the resistance of various types of temperature sensors with respect to temperature. (f–l Reproduced with permission from Ref. [46], © 2015, WILEY–VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim)

Figure 4f shows an illustration and optical image (inset) of a semitransparent piezoelectric strain sensor and resistive temperature sensor for measuring wrist motions and body-temperature changes for wheelchair control and hypothermia diagnosis, respectively. The strain sensor consists of a ZnO nanomembrane as the piezoelectric material and SWNT networks as the performance enhancer (Fig. 4g). The temperature sensor consists of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) embedded in the ZnO:Al (AZO) nanomembrane for improving its sensitivity (Fig. 4h). For the strain sensor, co-deposited Cr and SWNTs layers improve the crystallinity of ZnO and passivate intrinsic defects, respectively (Fig. 4i). These modifications dramatically amplify the piezoelectric voltage output of the intrinsic ZnO nanomembrane (Fig. 4j). For the temperature sensor, EC – EF (EC, minimum energy of the conduction band; EF, Fermi energy level) is proportional to the concentration of AgNPs inside the ZnO nanomembrane (Fig. 4k). The high concentration of AgNPs increases the carrier density and therefore improves the sensitivity of the temperature sensor (Fig. 4l). A more in-depth study of functional hybrid nanomaterials would provide new opportunities for high-performance wearable devices.

Wearable memories

Data recorded by wearable sensors should be either transferred or stored for the analysis. Usually, the data are stored in memory devices and retrieved when needed. In this section, two types of ultrathin deformable nonvolatile memory devices—charge-trap floating-gate memory (CTFM) [48] and resistive random access memory (RRAM) [41]—are described.

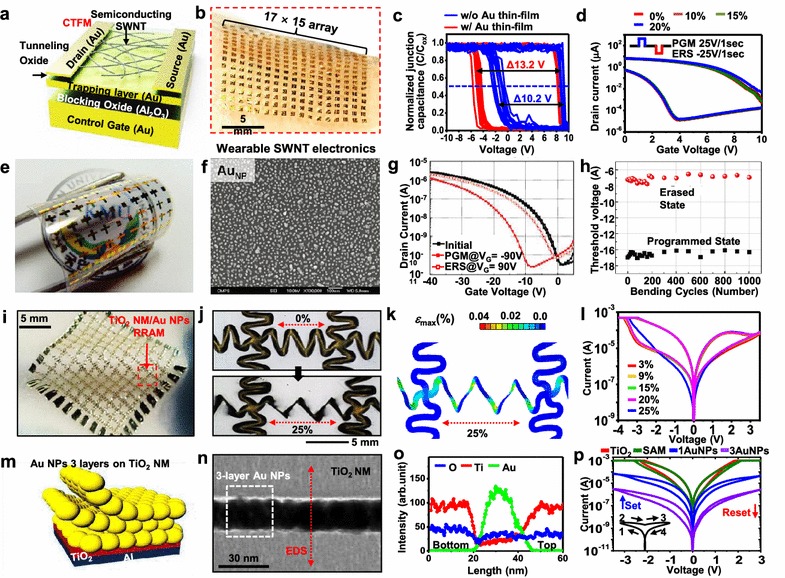

Deformable charge-trap floating-gate memory

Since the concept of memory devices using floating gates was first proposed [67], field-effect transistor (FET)-based CTFM has established itself as a dominant data storage device owing to its small area and compatibility with the CMOS process [68, 69]. For the realization of deformable CTFMs as next-generation devices, the rigid active materials are replaced with deformable ones such as organic materials [70, 71], SWNTs [48], 2D nanomembranes [72], and even inorganic SiNMs [73]. Figure 5a and b show the device structure of an SWNT-based CTFM and its laminated form on the human skin, respectively. The Au nanomembrane as a floating gate maximizes the charge capturing functionality (Fig. 5c). Soft active layers of SWNT networks are located at the neutral mechanical plane and allow stable operation under deformation.

Fig. 5.

Nanomaterials embedded wearable memory devices. a Schematic of CTFM. b Photograph of the CTFM array conformally attached to human skin. c C–V hysteresis curves of a CNT-based memory capacitor with (red) and without (blue) an Au thin-film floating gate. d Transfer curves of stretched (0–20 %) CTFM for the program and erase modes. (a–d Reproduced with permission from Ref. [48], © 2015, American Chemical Society). e Photograph of a flexible organic memory device with an AuNP floating gate. f SEM image of AuNPs attached to the blocking oxide. g Transfer curves of the flexible organic memory device for the initial, programmed, and erased states. h Threshold voltage of the flexible organic memory device for the programmed and erased states according to the number of bending cycles. (e–h Reproduced with permission from Ref. [71], © 2010, American Chemical Society). i Photograph showing wearable RRAM attached to a medical bandage. j Optical images of wearable RRAM in the initial (top) and stretched (bottom) states. k Finite-element-analysis results showing the strain distribution of stretched (25 %) wearable RRAM. l I–V characteristic curves of wearable RRAM for different stretched states. m Schematic structural view of three layers of AuNPs assembled on a TiO2 nanomembrane, n TEM image showing three layers of AuNPs embedded between TiO2 nanomembranes. o Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy results showing the quantitative material composition scanned along the red arrow in Fig. 5n. p I–V characteristic curves showing the bipolar switching of wearable RRAM for different trap materials. (i–p Reproduced with permission from Ref. [41], © 2014, Nature Publishing Group)

The floating gate of a continuous metal film has a critical limitation for the retention time [74]. Instead, metal nanoparticles (NPs) are a promising candidate as the floating gate to realize a fast program/erase speed and long retention time [74]. Figure 5e shows an optical image of a fabricated flexible CTFM using poly(4-vinylphenol) (PVP), pentacene, and gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) as the dielectric, semiconductor, and charge-trap layer, respectively. AuNPs are electrostatically adsorbed onto the PVP blocking oxide, thereby forming a monolayer of AuNPs (Fig. 5f). A large on/off window (>10 V) is obtained owing to the high density of AuNPs (Fig. 5g). Repetitive bending up to 1000 cycles with a bending radius of 20 mm does not diminish the performance of the CTFM.

Nanoparticle-embedded wearable RRAM

RRAM is another promising candidate for future nonvolatile memory devices [75–77]. By integrating RRAM with wearable sensors, a low power consumption and mechanical deformability are important for long-term use in mobile environments [41]. Figure 5i shows wearable RRAM consisting of AuNP charge-trap layers that reduce its operation current. Serpentine interconnections make the wearable RRAM stretchable up to 25 % strain (Fig. 5j–l). AuNPs embedded between TiO2 nanomembranes by Langmuir–Blodgett assembly form a uniform layer over a large area (Fig. 5m–o). The operation current of the wearable RRAM with one AuNP layer is decreased by one order of magnitude compared to that without AuNPs (Fig. 5p). Three layers of AuNPs exhibit a larger current decrease (by almost a factor of three).

Wearable displays

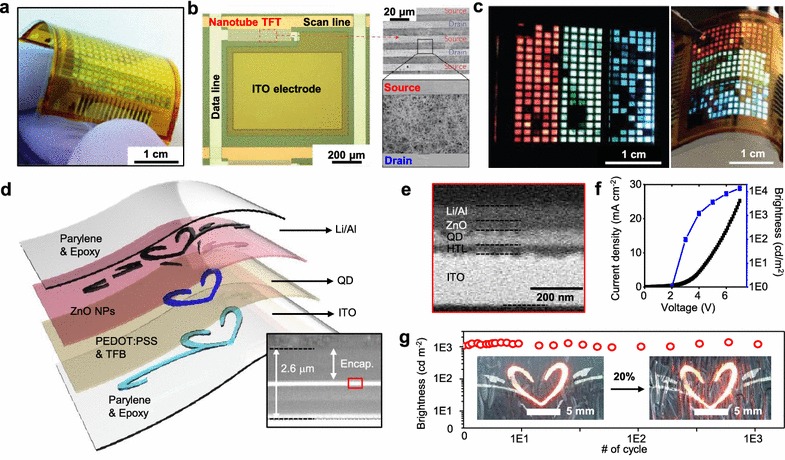

To construct user-interactive wearable electronic systems, deformable displays that visualize measured or stored data are indispensable for users. Recently, several breakthroughs in deformable LED technologies, including deformable inorganic/organic LEDs [51, 78–81], polymer LEDs [82–84], and quantum-dot LEDs (QLEDs) [85–87], have been reported.

Figure 6a–c show an image of a deformable actively multiplexed organic LED array, the device structure, and the bending capability, respectively. However, organic light-emitting materials have a low stability in air and a low photostability, and thus they need thick encapsulation under ambient conditions. Quantum dots, on the other hand, have favorable properties such as a good stability in air, good photostability, printability on various substrates, and a high brightness at low operating voltages, which are important key factors for deformable/wearable displays [88, 89]. Figure 6d and e show the structure of recently reported wearable QLED devices [44]. Thanks to ultrathin active and encapsulation layers, the total thickness of the device is ~ 2.6 μm, enabling conformal contact with the wearer’s skin. The wearable QLED is turned on at a low voltage (2 V; Fig. 6j) and endures 20 % stretching up to 1000 cycles without any degradation in its brightness (Fig. 6g). The use of biocompatible quantum dots and the replacement of the rigid transparent electrodes with soft ones further improve the practical applications of wearable QLEDs.

Fig. 6.

Deformable displays. a Photograph of a fabricated flexible OLED display containing 16 × 16 pixels. b Optical image of one pixel of the flexible OLED (left) and an enlarged view of the multiplexing CNT FET (right). c, Full-color flexible OLED display in which all pixels are turned on (left) and its bent form (right). (a–c Reproduced with permission from Ref. [50], © 2013, Nature Publishing Group). d Schematic exploded view showing the device structure of a wearable QLED and an SEM image showing the cross section of the display. e TEM image of the active layer indicated by the red box in the inset of d. f J–V–L characteristic curves of the wearable QLED. g Stable brightness of the wearable QLED during repetitive stretching cycles. Insets show the initial and stretched states of the wearable QLED. (d–g Reproduced with permission from Ref. [44], © 2015, Nature Publishing Group)

Wearable energy devices

Energy storage devices and power generators that supply power to wearable electronics need flexibility and biocompatibility. An all-solid-state supercapacitor (SC) [45, 49, 90, 91] is a suitable energy storage device with regard to this point. Moreover, SCs have a high power density, a fast charging/discharging speed, and cycle durability [92]. In case of the wearable power generators, flexible and soft fiber-based materials are suitable owing to the requirement of high deformability [28]. In this section, carbon-nanomaterial-based flexible SCs and organic nanofiber-based power generators are reviewed.

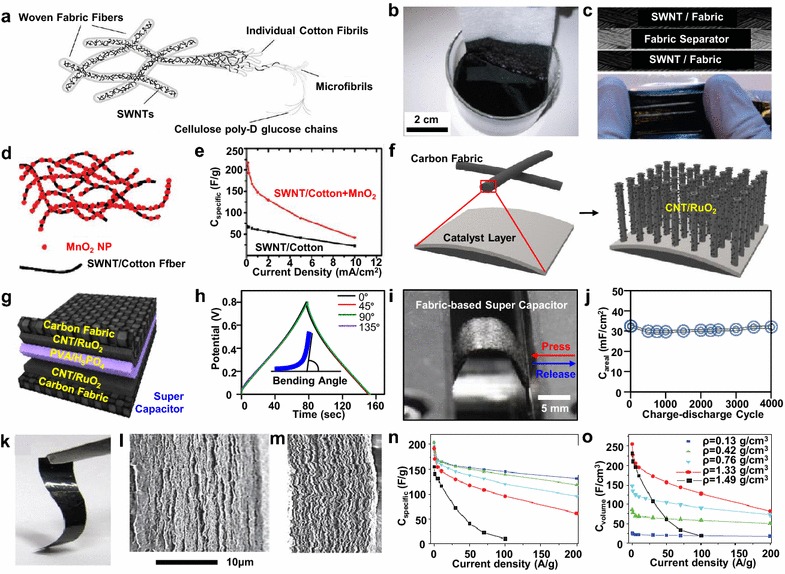

CNT-based wearable energy devices

The excellent electrochemical properties, electrical conductivity, large surface area, and mechanical softness of CNTs make them apt for the electrodes and current collectors of wearable SCs [93]. Cui et al. dipped fabric into a CNT-dispersed ink to coat the fabric fibers with CNT random networks (Fig. 7a, b) [49]. These engineered fabric electrodes assembled with a fabric separator in between form the SC (Fig. 7c). The large surface area of CNTs enables further decoration with other nanomaterials (e.g., pseudocapacitive metal oxide NPs such as MnO2 and RuO2) [94, 95]. The surface of the CNT fabric is electroplated with MnO2 NPs (Fig. 7d, e), which increases the specific capacitance.

Fig. 7.

Energy storage devices based on 1D/2D carbon nanomaterials. a Schematic microstructure of cotton fabric with random networks of CNTs inside. b Photograph of the cotton fabric dipped in the CNT ink. c Structure of the fabric-based supercapacitor (top) and a photograph when it is stretched (bottom). d Schematic of the SWNT/cotton fiber electroplated with MnO2 nanoparticles. e Specific capacitances of the supercapacitors with (red) and without (black) MnO2 within the current density range of 0–10 mA/cm2. (a–e Reproduced with permission from Ref. [49], © 2010, American Chemical Society). f Schematic of the vertical CNT forest grown on the carbon fabric and electroplated with RuO2 nanoparticles. g Schematic exploded view of the carbon-fabric-based wearable supercapacitor. h Galvanostatic charge–discharge curves of the wearable supercapacitor at different bending angles. i Photograph showing the fabric-based supercapacitor while bent. j Areal capacitances of the supercapacitor for different charge–discharge cycles. (f–j Reproduced with permission from [45], © 2014, WILEY–VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim). k Photograph of the GP-stacked film. l–m SEM images of the cross sections of the GP film with l 78.9 and m 27.2 vol% of H2SO4. n Specific and o volumetric capacitances of the GP-based supercapacitors with different packing densities (ρ) for different current densities. (k–o Reproduced with permission from Ref. [15], © 2013, American Association for the Advancement of Science)

Instead of coating fabrics, carbon fibers are used to make a woven fabric, which can be applied to flexible textile electrodes [45]. To maximize the surface area, vertically-aligned CNTs are additionally synthesized on the carbon fabric. Electroplating vertical CNTs with RuO2 NPs further increases the capacitance (Fig. 7f), and an all-solid-state wearable SC is fabricated by sandwiching a poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA)-H3PO4 gel electrolyte between two modified carbon fabric electrodes (Fig. 7g). The resulting SC exhibits high performance up to 135-degree bending and 4000 charge–discharge cycles (Fig. 7h–j).

GP-based wearable energy devices

Multiple chemically converted GP sheets are beneficial for fast ion transport [15]. GP flakes and/or reduced GP oxides are densely packed by capillary pressure to fabricate flexible carbon electrodes (Fig. 7k). The packing density (ρ) of the GP sheets can be controlled by changing the ratio of the volatile and nonvolatile liquids in the gel (Fig. 7l, m). Figure 7n and o show the specific capacitance and volumetric capacitance, respectively, of SCs using stacked GP electrodes for different values of ρ. The specific capacitance slightly decreases as ρ increases, whereas the volumetric capacitance is nearly proportional to ρ. Although most SCs made of activated carbon exhibit a volumetric energy density of 5–8 Wh/L, SCs made of the GP assembly exhibit a volumetric energy density of 60 Wh/L, which is similar to that of lead-acid batteries (50–90 Wh/L).

Organic nanofiber-based wearable power generators

To harvest electrical energy from body movements, piezoelectric nanogenerators (PENGs) and triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) have been used [28, 96]. Organic nanofibers such as polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) formed by using electrospinning processes have shown superb deformability as well as high piezoresistivity, facilitating its use in wearable applications [18, 28]. Piezoelectric power generation using a single PVDF nanofiber [97], aligned multiple PVDF nanofibers [98, 99], and randomly distributed nanofiber networks [100] have been demonstrated. Parallel and series connection of PVDF nanofibers increase the generated voltage and current [98]. However, relatively low output power of PENGs has limited the application for wearable devices with high power consumption [28]. In contrast, TENGs have shown much higher output power than PENGs [28]. Electrospun PVDF nanofibers are also suitable for fabrication of the TENG because of their strong electronegativity and high porous morphology offering large contact area to increase the output power [28, 101]. The PVDF nanofiber-based TENG has been recently demonstrated as wearable forms [28]. Seamless integration of the organic nanofiber-based wearable power generators with energy storage devices and control circuits is another important future research topic.

Conclusions

The mechanical, electrical, and optical properties of bulk materials change as their size is reduced and/or nanoscale structure engineering is introduced. By using the unique properties of such nanomaterials or their hybrids, many breakthroughs in wearable devices have been accomplished. In this paper, we reviewed the current status of wearable devices including sensors/actuators, memory devices, displays, and energy storage devices. We particularly focused on the use of functional nanomaterials to enhancing the deformability and performance of these devices. Continuous research and development of new nanomaterials/hybrids and their integration into variety of electronic/optoelectronic devices would provide new opportunities for next-generation wearable electronics.

Authors’ contributions

JK and JL contributed equally. JK, JL, and D-HK wrote the manuscript. JK, JL, DS, MKC and D-HK designed the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by IBS-R006-D1. This work was supported by a Seoul National University Research Grant.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Jaemin Kim and Jongsu Lee contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Jaemin Kim, Email: zephyr@snu.ac.kr.

Jongsu Lee, Email: yukgagsu@gmail.com.

Donghee Son, Email: daniel3600@snu.ac.kr.

Moon Kee Choi, Email: cmgj1436@snu.ac.kr.

Dae-Hyeong Kim, Email: dkim98@snu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Lim S, Son D, Kim J, Lee YB, Song JK, Choi S, Lee DJ, Kim JH, Lee M, Hyeon T, Kim DH. Transparent and stretchable interactive human machine interface based on patterned graphene heterostructures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015;25:375–383. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201402987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J, Lee M, Rhim J, Wang P, Lu N, Kim D-H. Next-generation flexible neural and cardiac electrode arrays. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2014;4:95–108. doi: 10.1007/s13534-014-0132-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim DH, Ahn JH, Choi WM, Kim HS, Kim TH, Song JZ, Huang YGY, Liu ZJ, Lu C, Rogers JA. Stretchable and foldable silicon integrated circuits. Science. 2008;320:507–511. doi: 10.1126/science.1154367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim DH, Ghaffari R, Lu NS, Rogers JA. Flexible and stretchable electronics for biointegrated devices. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2012;14:113–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071811-150018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim DH, Lu NS, Ghaffari R, Rogers JA. Inorganic semiconductor nanomaterials for flexible and stretchable bio-integrated electronics. NPG Asia Mater. 2012;4:e15. doi: 10.1038/am.2012.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim DH, Xiao JL, Song JZ, Huang YG, Rogers JA. Stretchable, curvilinear electronics based on inorganic materials. Adv. Mater. 2010;22:2108–2124. doi: 10.1002/adma.200902927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim J, Lee M, Shim HJ, Ghaffari R, Cho HR, Son D, Jung YH, Soh M, Choi C, Jung S, Chu K, Jeon D, Lee ST, Kim JH, Choi SH, Hyeon T, Kim DH. Stretchable silicon nanoribbon electronics for skin prosthesis. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5747. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ying M, Bonifas AP, Lu NS, Su YW, Li R, Cheng HY, Ameen A, Huang YG, Rogers JA. Silicon nanomembranes for fingertip electronics. Nanotechnology. 2012;23:344004. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/23/34/344004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim DH, Lu NS, Huang YG, Rogers JA. Materials for stretchable electronics in bioinspired and biointegrated devices. MRS Bull. 2012;37:226–235. doi: 10.1557/mrs.2012.36. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viventi J, Kim DH, Vigeland L, Frechette ES, Blanco JA, Kim YS, Avrin AE, Tiruvadi VR, Hwang SW, Vanleer AC, Wulsin DF, Davis K, Gelber CE, Palmer L, Van der Spiegel J, Wu J, Xiao JL, Huang YG, Contreras D, Rogers JA, Litt B. Flexible, foldable, actively multiplexed, high-density electrode array for mapping brain activity in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:1599–1605. doi: 10.1038/nn.2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim D-H, Choi WM, Ahn J-H, Kim H-S, Song J, Huang Y, Liu Z, Lu C, Koh CG, Rogers JA. Complementary metal oxide silicon integrated circuits incorporating monolithically integrated stretchable wavy interconnects. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008;93:044102. doi: 10.1063/1.2963364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hata K, Futaba DN, Mizuno K, Namai T, Yumura M, Iijima S. Water-assisted highly efficient synthesis of impurity-free single-waited carbon nanotubes. Science. 2004;306:1362–1364. doi: 10.1126/science.1104962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamada T, Hayamizu Y, Yamamoto Y, Yomogida Y, Izadi-Najafabadi A, Futaba DN, Hata K. A stretchable carbon nanotube strain sensor for human-motion detection. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011;6:296–301. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roh E, Hwang BU, Kim D, Kim BY, Lee NE. Stretchable, transparent, ultrasensitive, and patchable strain sensor for human-machine interfaces comprising a nanohybrid of carbon nanotubes and conductive elastomers. ACS Nano. 2015;9:6252–6261. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b01613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang XW, Cheng C, Wang YF, Qiu L, Li D. Liquid-mediated dense integration of graphene materials for compact capacitive energy storage. Science. 2013;341:534–537. doi: 10.1126/science.1239089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SM, Kim JH, Ahn JH. Graphene as a flexible electronic material: mechanical limitations by defect formation and efforts to overcome. Mater. Today. 2015;18:336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2015.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min SY, Kim TS, Lee Y, Cho H, Xu W, Lee TW. Organic nanowire fabrication and device applications. Small. 2015;11:45–62. doi: 10.1002/smll.201401487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang JY, Domnner M, Chang C, Lin LW. Piezoelectric nanofibers for energy scavenging applications. Nano Energy. 2012;1:356–371. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2012.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang H, Lee W, Won SM, Ryu SY, Lee D, Koo JB, Ahn SD, Yang CW, Jo MH, Cho JH, Rogers JA, Ahn JH. Quantum confinement effects in transferrable silicon nanomembranes and their applications on unusual substrates. Nano Lett. 2013;13:5600–5607. doi: 10.1021/nl403251e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim DH, Ahn JH, Kim HS, Lee KJ, Kim TH, Yu CJ, Nuzzo RG, Rogers JA. Complementary logic gates and ring oscillators on plastic substrates by use of printed ribbons of single-crystalline silicon. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2008;29:73–76. doi: 10.1109/LED.2007.910770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durkop T, Getty SA, Cobas E, Fuhrer MS. Extraordinary mobility in semiconducting carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2004;4:35–39. doi: 10.1021/nl034841q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolotin KI, Sikes KJ, Jiang Z, Klima M, Fudenberg G, Hone J, Kim P, Stormer HL. Ultrahigh electron mobility in suspended graphene. Solid State Commun. 2008;146:351–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ssc.2008.02.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Artukovic E, Kaempgen M, Hecht DS, Roth S, GrUner G. Transparent and flexible carbon nanotube transistors. Nano Lett. 2005;5:757–760. doi: 10.1021/nl050254o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu LB, Yuan W, Brochu P, Gruner G, Pei QB. Highly stretchable, conductive, and transparent nanotube thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009;94:161108. doi: 10.1063/1.3114463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nair RR, Blake P, Grigorenko AN, Novoselov KS, Booth TJ, Stauber T, Peres NMR, Geim AK. Fine structure constant defines visual transparency of graphene. Science. 2008;320:1308. doi: 10.1126/science.1156965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Volder MFL, Tawfick SH, Baughman RH, Hart AJ. Carbon nanotubes: present and future commercial applications. Science. 2013;339:535–539. doi: 10.1126/science.1222453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Min SY, Kim TS, Kim BJ, Cho H, Noh YY, Yang H, Cho JH, Lee TW. Large-scale organic nanowire lithography and electronics. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1773. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang T, Wang C, Yu H, Wang HZ, Zhang QH, Zhu MF. Human walking-driven wearable all-fiber triboelectric nanogenerator containing electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride piezoelectric nanofibers. Nano Energy. 2015;14:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2015.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gheibi A, Latifi M, Merati AA, Bagherzadeh R. Piezoelectric electrospun nanofibrous materials for self-powering wearable electronic textiles applications. J. Polym. Res. 2014;21:469. doi: 10.1007/s10965-014-0469-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang X, Tan CL, Yin ZY, Zhang H. 25th anniversary article: hybrid nanostructures based on two-dimensional nanomaterials. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:2185–2204. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan Z, Ma LL, Zhu Y, Lahiri I, Hahm MG, Liu Z, Yang SB, Xiang CS, Lu W, Peng ZW, Sun ZZ, Kittrell C, Lou J, Choi WB, Ajayan PM, Tour JM. Three-dimensional metal–graphene–nanotube multifunctional hybrid materials. ACS Nano. 2013;7:58–64. doi: 10.1021/nn3015882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh LP, Srivastava K, Mishra R, Ningthoujam RS. Multifunctional hybrid nanomaterials from water dispersible CaF2:Eu3+, Mn2+ and Fe3O4 for luminescence and hyperthermia application. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:18087–18096. doi: 10.1021/jp502825p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strassert CA, Otter M, Albuquerque RQ, Hone A, Vida Y, Maier B, De Cola L. Photoactive hybrid nanomaterial for targeting, labeling, and killing antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2009;48:7928–7931. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fahmi A, Pietsch T, Mendoza C, Cheval N. Functional hybrid materials. Mater. Today. 2009;12:44–50. doi: 10.1016/S1369-7021(09)70159-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Son D, Lee J, Lee DJ, Ghaffari R, Yun S, Kim SJ, Lee JE, Cho HR, Yoon S, Yang SX, Lee S, Qiao ST, Ling DS, Shin S, Song JK, Kim J, Kim T, Lee H, Kim J, Soh M, Lee N, Hwang CS, Nam S, Lu NS, Hyeon T, Choi SH, Kim DH. Bioresorbable electronic stent integrated with therapeutic nanoparticles for endovascular diseases. ACS Nano. 2015;9:5937–5946. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b00651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SJ, Cho HR, Cho KW, Qiao ST, Rhim JS, Soh M, Kim T, Choi MK, Choi C, Park I, Hwang NS, Hyeon T, Choi SH, Lu NS, Kim DH. Multifunctional cell-culture platform for aligned cell sheet monitoring, transfer printing, and therapy. ACS Nano. 2015;9:2677–2688. doi: 10.1021/nn5064634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeng SW, Baillargeat D, Ho HP, Yong KT. Nanomaterials enhanced surface plasmon resonance for biological and chemical sensing applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:3426–3452. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60479a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buzea C, Pacheco II, Robbie K. Nanomaterials and nanoparticles: sources and toxicity. Biointerphases. 2007;2:MR17–172. doi: 10.1116/1.2815690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park TJ, Papaefthymiou GC, Viescas AJ, Moodenbaugh A, Wong SS. Size-dependent magnetic properties of single-crystalline multiferroic BiFeO3 nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2007;7:766–772. doi: 10.1021/nl063039w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo D, Xie GX, Luo JB. Mechanical properties of nanoparticles: basics and applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014;47:013001. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/47/1/013001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Son D, Lee J, Qiao S, Ghaffari R, Kim J, Lee JE, Song C, Kim SJ, Lee DJ, Jun SW, Yang S, Park M, Shin J, Do K, Lee M, Kang K, Hwang CS, Lu NS, Hyeon T, Kim DH. Multifunctional wearable devices for diagnosis and therapy of movement disorders. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014;9:397–404. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi S, Park J, Hyun W, Kim J, Kim J, Lee YB, Song C, Hwang HJ, Kim JH, Hyeon T, Kim DH. Stretchable heater using ligand-exchanged silver nanowire nanocomposite for wearable articular thermotherapy. ACS Nano. 2015;9:6626–6633. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b02790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi MK, Park OK, Choi C, Qiao S, Ghaffari R, Kim J, Lee DJ, Kim M, Hyun W, Kim SJ, Hwang HJ, Kwon S-H, Hyeon T, Lu N, Kim D-H. Cephalopod-inspired miniaturized suction cups for smart medical skin. Adv. Healthc. Mater. Early View. 2015;5:80–87. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi MK, Yang J, Kang K, Kim DC, Choi C, Park C, Kim SJ, Chae SI, Kim TH, Kim JH, Hyeon T, Kim DH. Wearable red–green–blue quantum dot light-emitting diode array using high-resolution intaglio transfer printing. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7149. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jung S, Lee J, Hyeon T, Lee M, Kim DH. Fabric-based integrated energy devices for wearable activity monitors. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:6329–6334. doi: 10.1002/adma.201402439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park M, Do K, Kim J, Son D, Koo JH, Park J, Song J-K, Kim JH, Lee M, Hyeon T, Kim D-H. Oxide nanomembrane hybrids with enhanced mechano- and thermo-sensitivity for semitransparent epidermal electronics. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2015;4:992–997. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jung S, Kim JH, Kim J, Choi S, Lee J, Park I, Hyeon T, Kim DH. Reverse-micelle-induced porous pressure-sensitive rubber for wearable human-machine interfaces. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:4825–4830. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Son D, Koo JH, Song JK, Kim J, Lee M, Shim HJ, Park M, Lee M, Kim JH, Kim DH. Stretchable carbon nanotube charge-trap floating-gate memory and logic devices for wearable electronics. ACS Nano. 2015;9:5585–5593. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b01848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu L, Pasta M, Mantia FL, Cui L, Jeong S, Deshazer HD, Choi JW, Han SM, Cui Y. Stretchable, porous, and conductive energy textiles. Nano Lett. 2010;10:708–714. doi: 10.1021/nl903949m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang C, Hwang D, Yu ZB, Takei K, Park J, Chen T, Ma BW, Javey A. User-interactive electronic skin for instantaneous pressure visualization. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:899–904. doi: 10.1038/nmat3711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sekitani T, Nakajima H, Maeda H, Fukushima T, Aida T, Hata K, Someya T. Stretchable active-matrix organic light-emitting diode display using printable elastic conductors. Nat. Mater. 2009;8:494–499. doi: 10.1038/nmat2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Warner JH, Young NP, Kirkland AI, Briggs GAD. Resolving strain in carbon nanotubes at the atomic level. Nat. Mater. 2011;10:958–962. doi: 10.1038/nmat3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Urban KW. Electron microscopy the challenges of graphene. Nat. Mater. 2011;10:165–166. doi: 10.1038/nmat2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel S, Park H, Bonato P, Chan L, Rodgers M. A review of wearable sensors and systems with application in rehabilitation. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2012;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ponce BA, Menendez ME, Oladeji LO, Fryberger CT, Dantuluri PK. Emerging technology in surgical education: combining real-time augmented reality and wearable computing devices. Orthopedics. 2014;37:751–757. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20141023-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao L, Zhang YH, Malyarchuk V, Jia L, Jang KI, Webb RC, Fu HR, Shi Y, Zhou GY, Shi LK, Shah D, Huang X, Xu BX, Yu CJ, Huang YG, Rogers JA. Epidermal photonic devices for quantitative imaging of temperature and thermal transport characteristics of the skin. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4938. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Webb RC, Bonifas AP, Behnaz A, Zhang YH, Yu KJ, Cheng HY, Shi MX, Bian ZG, Liu ZJ, Kim YS, Yeo WH, Park JS, Song JZ, Li YH, Huang YG, Gorbach AM, Rogers JA. Ultrathin conformal devices for precise and continuous thermal characterization of human skin. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:938–944. doi: 10.1038/nmat3755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yeo WH, Kim YS, Lee J, Ameen A, Shi LK, Li M, Wang SD, Ma R, Jin SH, Kang Z, Huang YG, Rogers JA. Multifunctional epidermal electronics printed directly onto the skin. Adv. Mater. 2013;25:2773–2778. doi: 10.1002/adma.201204426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jeong JW, Kim MK, Cheng HY, Yeo WH, Huang X, Liu YH, Zhang YH, Huang YG, Rogers JA. Capacitive epidermal electronics for electrically safe, long-term electrophysiological measurements. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014;3:642–648. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim DH, Lu NS, Ma R, Kim YS, Kim RH, Wang SD, Wu J, Won SM, Tao H, Islam A, Yu KJ, Kim TI, Chowdhury R, Ying M, Xu LZ, Li M, Chung HJ, Keum H, McCormick M, Liu P, Zhang YW, Omenetto FG, Huang YG, Coleman T, Rogers JA. Epidermal electronics. Science. 2011;333:838–843. doi: 10.1126/science.1206157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jeong JW, Yeo WH, Akhtar A, Norton JJS, Kwack YJ, Li S, Jung SY, Su YW, Lee W, Xia J, Cheng HY, Huang YG, Choi WS, Bretl T, Rogers JA. Materials and optimized designs for human-machine interfaces via epidermal electronics. Adv. Mater. 2013;25:6839–6846. doi: 10.1002/adma.201301921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Viventi J, Kim DH, Moss JD, Kim YS, Blanco JA, Annetta N, Hicks A, Xiao JL, Huang YG, Callans DJ, Rogers JA, Litt B. A conformal, bio-interfaced class of silicon electronics for mapping cardiac electrophysiology. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010;2:24ra22. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moniruzzaman M, Winey KI. Polymer nanocomposites containing carbon nanotubes. Macromolecules. 2006;39:5194–5205. doi: 10.1021/ma060733p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fiedler B, Gojny FH, Wichmann MHG, Nolte MCM, Schulte K. Fundamental aspects of nano-reinforced composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2006;66:3115–3125. doi: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2005.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sharma BK, Jang B, Lee JE, Bae SH, Kim TW, Lee HJ, Kim JH, Ahn JH. Load-controlled roll transfer of oxide transistors for stretchable electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013;23:2024–2032. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201202519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee H, Lee Y, Song C, Cho HR, Ghaffari R, Choi TK, Kim KH, Lee YB, Ling D, Lee H, Yu SJ, Choi SH, Hyeon T, Kim DH. An endoscope with integrated transparent bioelectronics and theranostic nanoparticles for colon cancer treatment. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:10059. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kahng D, Sze SM. A floating gate and its application to memory devices. Bell Sys. Tech. J. 1967;46:1288–1295. doi: 10.1002/j.1538-7305.1967.tb01738.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meena JS, Sze SM, Chand U, Tseng TY. Overview of emerging nonvolatile memory technologies. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014;9:526. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-9-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bez R, Camerlenghi E, Modelli A, Visconti A. Introduction to flash memory. Proc IEEE. 2003;91:489–502. doi: 10.1109/JPROC.2003.811702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sekitani T, Yokota T, Zschieschang U, Klauk H, Bauer S, Takeuchi K, Takamiya M, Sakurai T, Someya T. Organic nonvolatile memory transistors for flexible sensor arrays. Science. 2009;326:1516–1519. doi: 10.1126/science.1179963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim S-J, Lee J-S. Flexible organic transistor memory devices. Nano Lett. 2010;10:2884–2890. doi: 10.1021/nl1009662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim SM, Song EB, Lee S, Zhu JF, Seo DH, Mecklenburg M, Seo S, Wang KL. Transparent and flexible graphene charge-trap memory. ACS Nano. 2012;6:7879–7884. doi: 10.1021/nn302193q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim J, Son D, Lee M, Song C, Song J-K, Koo JH, Lee DJ, Shim HJ, Kim JH, Lee M, Hyeon T, Kim DH. A wearable multiplexed silicon nonvolatile memory array using nanocrystal charge confinement. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1501101. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee J-S. Recent progress in gold nanoparticle-based non-volatile memory devices. Gold Bull. 2010;43:189–199. doi: 10.1007/BF03214986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Waser R, Aono M. Nanoionics-based resistive switching memories. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:833–840. doi: 10.1038/nmat2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kwon DH, Kim KM, Jang JH, Jeon JM, Lee MH, Kim GH, Li XS, Park GS, Lee B, Han S, Kim M, Hwang CS. Atomic structure of conducting nanofilaments in TiO2 resistive switching memory. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010;5:148–153. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Borghetti J, Snider GS, Kuekes PJ, Yang JJ, Stewart DR, Williams RS. ‘Memristive’ switches enable ‘stateful’ logic operations via material implication. Nature. 2010;464:873–876. doi: 10.1038/nature08940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim RH, Kim DH, Xiao JL, Kim BH, Park SI, Panilaitis B, Ghaffari R, Yao JM, Li M, Liu ZJ, Malyarchuk V, Kim DG, Le AP, Nuzzo RG, Kaplan DL, Omenetto FG, Huang YG, Kang Z, Rogers JA. Waterproof AlInGaP optoelectronics on stretchable substrates with applications in biomedicine and robotics. Nat. Mater. 2010;9:929–937. doi: 10.1038/nmat2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim TI, McCall JG, Jung YH, Huang X, Siuda ER, Li YH, Song JZ, Song YM, Pao HA, Kim RH, Lu CF, Lee SD, Song IS, Shin G, Al-Hasani R, Kim S, Tan MP, Huang YG, Omenetto FG, Rogers JA, Bruchas MR. Injectable, cellular-scale optoelectronics with applications for wireless optogenetics. Science. 2013;340:211–216. doi: 10.1126/science.1232437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Park SI, Xiong YJ, Kim RH, Elvikis P, Meitl M, Kim DH, Wu J, Yoon J, Yu CJ, Liu ZJ, Huang YG, Hwang K, Ferreira P, Li XL, Choquette K, Rogers JA. Printed assemblies of inorganic light-emitting diodes for deformable and semitransparent displays. Science. 2009;325:977–981. doi: 10.1126/science.1175690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Han TH, Lee Y, Choi MR, Woo SH, Bae SH, Hong BH, Ahn JH, Lee TW. Extremely efficient flexible organic light-emitting diodes with modified graphene anode. Nat. Photon. 2012;6:105–110. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2011.318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liang JJ, Li L, Niu XF, Yu ZB, Pei QB. Elastomeric polymer light-emitting devices and displays. Nat. Photon. 2013;7:817–824. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2013.242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yu ZB, Niu XF, Liu ZT, Pei QB. Intrinsically stretchable polymer light-emitting devices using carbon nanotube-polymer composite electrodes. Adv. Mater. 2011;23:3989–3994. doi: 10.1002/adma.201101986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.White MS, Kaltenbrunner M, Glowacki ED, Gutnichenko K, Kettlgruber G, Graz I, Aazou S, Ulbricht C, Egbe DAM, Miron MC, Major Z, Scharber MC, Sekitani T, Someya T, Bauer S, Sariciftci NS. Ultrathin, highly flexible and stretchable pleds. Nat. Photon. 2013;7:811–816. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2013.188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim TH, Cho KS, Lee EK, Lee SJ, Chae J, Kim JW, Kim DH, Kwon JY, Amaratunga G, Lee SY, Choi BL, Kuk Y, Kim JM, Kim K. Full-colour quantum dot displays fabricated by transfer printing. Nat. Photon. 2011;5:176–182. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2011.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang XY, Mutlugun E, Dang C, Dev K, Gao Y, Tan ST, Sun XW, Demir HV. Highly flexible, electrically driven, top-emitting, quantum dot light-emitting stickers. ACS Nano. 2014;8:8224–8231. doi: 10.1021/nn502588k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Choi MK, Park I, Kim DC, Joh E, Park OK, Kim J, Kim M, Choi C, Yang J, Cho KW, Hwang J-H, Nam J-M, Hyeon T, Kim JH, Kim D-H. Thermally controlled, patterned graphene transfer printing for transparent and wearable electronic/optoelectronic system. Adv. Funct. Mater. Early View. 2015;9:7109–7118. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201502956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kwak J, Bae WK, Lee D, Park I, Lim J, Park M, Cho H, Woo H, Yoon DY, Char K, Lee S, Lee C. Bright and efficient full-color colloidal quantum dot light-emitting diodes using an inverted device structure. Nano Lett. 2012;12:2362–2366. doi: 10.1021/nl3003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dai XL, Zhang ZX, Jin YZ, Niu Y, Cao HJ, Liang XY, Chen LW, Wang JP, Peng XG. Solution-processed, high-performance light-emitting diodes based on quantum dots. Nature. 2014;515:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature13829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kang YJ, Chun SJ, Lee SS, Kim BY, Kim JH, Chung H, Lee SY, Kim W. All-solid-state flexible supercapacitors fabricated with bacterial nanocellulose papers, carbon nanotubes, and triblock-copolymer ion gels. ACS Nano. 2012;6:6400–6406. doi: 10.1021/nn301971r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xiao X, Li TQ, Yang PH, Gao Y, Jin HY, Ni WJ, Zhan WH, Zhang XH, Cao YZ, Zhong JW, Gong L, Yen WC, Mai WJ, Chen J, Huo KF, Chueh YL, Wang ZL, Zhou J. Fiber-based all-solid-state flexible supercapacitors for self-powered systems. ACS Nano. 2012;6:9200–9206. doi: 10.1021/nn303530k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Simon P, Gogotsi Y. Materials for electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Mater. 2008;7:845–854. doi: 10.1038/nmat2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Futaba DN, Hata K, Yamada T, Hiraoka T, Hayamizu Y, Kakudate Y, Tanaike O, Hatori H, Yumura M, Iijima S. Shape-engineerable and highly densely packed single-walled carbon nanotubes and their application as super-capacitor electrodes. Nat. Mater. 2006;5:987–994. doi: 10.1038/nmat1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang H, Cao GP, Wang ZY, Yang YS, Shi ZJ, Gu ZN. Growth of manganese oxide nanoflowers on vertically-aligned carbon nanotube arrays for high-rate electrochemical capacitive energy storage. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2664–2668. doi: 10.1021/nl800925j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ye JS, Cui HF, Liu X, Lim TM, Zhang WD, Sheu FS. Preparation and characterization of aligned carbon nanotube-ruthenium oxide nanocomposites for supercapacitors. Small. 2005;1:560–565. doi: 10.1002/smll.200400137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jung S, Hong S, Kim J, Lee S, Hyeon T, Lee M, Kim DH. Wearable fall detector using integrated sensors and energy devices. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:17081. doi: 10.1038/srep17081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chang CE, Tran VH, Wang JB, Fuh YK, Lin LW. Direct-write piezoelectric polymeric nanogenerator with high energy conversion efficiency. Nano Lett. 2010;10:726–731. doi: 10.1021/nl9040719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.J. Chang, L. Lin, Large array electrospun PVDF nanogenerators on a flexible substrate. Paper presented at the 16th international conference on solid-state sensors, actuators and microsystems (TRANSDUCERS), Beijing, 5–9 June 2011

- 99.Hansen BJ, Liu Y, Yang RS, Wang ZL. Hybrid nanogenerator for concurrently harvesting biomechanical and biochemical energy. ACS Nano. 2010;4:3647–3652. doi: 10.1021/nn100845b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fang J, Wang XG, Lin T. Electrical power generator from randomly oriented electrospun poly(vinylidene fluoride) nanofibre membranes. J. Mater. Chem. 2011;21:11088–11091. doi: 10.1039/c1jm11445j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Diaz AF, Felix-Navarro RM. A semi-quantitative tribo-electric series for polymeric materials: the influence of chemical structure and properties. J. Electrostat. 2004;62:277–290. doi: 10.1016/j.elstat.2004.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]