Abstract

Objective

Data gathered via retrospective forms of assessment are subject to various recall biases. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is an alternative approach involving repeated momentary assessments within a participant's natural environment, thus reducing recall biases and improving ecological validity. EMA has been used in numerous prior studies examining various constructs of theoretical relevance to eating disorders.

Method

This investigation includes data from three previously published studies with distinct clinical samples: (a) women with anorexia nervosa (N=118), (b) women with bulimia nervosa (N=133), and (c) obese men and women (N=50; 9 with current binge eating disorder). Each study assessed negative affective states and eating disorder behaviors using traditional retrospective assessments and EMA. Spearman rho correlations were used to evaluate the concordance of retrospective versus EMA measures of affective and/or behavioral constructs in each sample. Bland-Altman plots were also used to further evaluate concordance in the assessment of eating disorder behaviors.

Results

There was moderate to strong concordance for the measures of negative affective states across all three studies. Moderate to strong concordance was also found for the measures of binge eating and exercise frequency. The strongest evidence of concordance across measurement approaches was found for purging behaviors.

Discussion

Overall, these preliminary findings support the convergence of retrospective and EMA assessments of both negative affective states and various eating disorder behaviors. Given the advantages and disadvantages associated with each of these assessment approaches, the specific questions being studied in future empirical studies should inform decisions regarding selection of the most appropriate method.

Keywords: ecological momentary assessment, negative affect, depression, binge eating, purging

Approaches to the assessment of eating disorder behaviors and related clinically relevant constructs (e.g., affective variables) in eating disorder samples remain a source of ongoing debate and discussion in the literature [1,2]. These constructs are most commonly assessed with a variety of retrospective semi-structured interviews (e.g., Eating Disorder Examination [3], Structured Interview for Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa [4], Eating Disorder Assessment-5 [5]) and/or questionnaires (e.g., Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire [6], Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale [7], Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory [8]). Existing research has addressed issues of convergence across questionnaires versus interview-based assessments [1], as well as face-to-face versus telephone-based interviews [9]. However, these retrospective forms of assessment may be limited by individuals' difficulty recalling emotional experiences and behaviors accurately [2]. In particular, various biases may contribute to recall difficulties, including cognitive and memory limitations, effort after meaning, and the impact of current mental states on ability to recall past mental states [2].

One approach that researchers have taken to reduce limitations associated with traditional retrospective assessment approaches is to use alternative methodologies, such as ecological momentary assessment (EMA [10]). EMA employs portable measurement strategies and involves repeated assessments over the course of a given timeframe in a participant's natural environment as events of interest occur (e.g., affective experiences, eating disorder behaviors; [2]). This `real-time' and naturalistic approach to assessment provides benefits over traditional assessment methods including reduced reliance on retrospective recall, increased ability to examine temporal associations between variables in a short-term timeframe, and greater ecological validity compared to laboratory-based research. EMA has been applied in multiple areas of psychopathology and behavioral medicine, including stress and coping, substance use, chronic pain, and eating disorders and obesity [11–16].

One question of relevance to comparing findings across studies utilizing EMA versus traditional retrospective measures is the extent to which there is convergence of data gathered across these differing assessment formats. As such, the goal of the current study was to examine the degree of association between retrospective versus EMA measures of certain affective (e.g., negative affect/depressive symptoms) and behavioral (e.g., frequency of eating disorder symptoms) constructs using data from three separate studies, each associated with a distinct clinical sample (i.e., individuals with anorexia nervosa [AN], bulimia nervosa [BN], or obesity [OB]). We hypothesized that there would be moderate convergence for all variables across the two assessment formats.

METHOD

Participants

Participants in the current study were drawn from three distinct clinical samples that utilized EMA to examine eating disorder behaviors, affect, and other variables. Demographic data for each sample are presented in Table 1. The first sample was comprised of 118 female participants who met the criteria for either full DSM-IV [17] or subthreshold AN. Subthreshold AN was defined as meeting all DSM-IV criteria for AN except: (a) body mass index between 17.5 and 18.5 kg/m2, or (b) absence of amenorrhea, or (c) an absence of the cognitive features of AN. On the basis of these assessments, 121 participants met eligibility criteria, agreed to participate, and were enrolled in the study. Three participants had EMA compliance rates of less than 50% and were excluded from analyses, resulting in a final total of 118 participants. Additional information on the sample is available in Engel et al. [15] and Le Grange et al. [18].

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics and EMA Recording Descriptive Data

| AN Sample (n = 118) | BN Sample (n = 133) | Obesity Sample (n = 50) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 25.3 ± 8.4 | 25.3 ± 7.6 | 43.0 ± 11.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 17.2 ± 1.0 | 23.9 ± 5.2 | 40.3 ± 8.5 |

| Sex (% female) | 100% | 100% | 84% |

| Ethnicity (% Caucasian) | 96.6% | 95.5% | 76.0% |

| EMA Descriptive Data | |||

| Number of EMA Recordings | 14,945 | 13,055 | 7,524 |

| EMA Random Signal Compliance | 77% | 86% | 81% |

The second sample consisted of 133 female participants who met DSM-IV criteria for BN. From a pool of 143 participants who began the EMA protocol, 7 participants dropped out of the EMA protocol before completion, and 3 participants provided incomplete data on the EMA, resulting in a final total of 133 participants. Additional information on this sample is available in Smyth et al. [14].

The third sample was comprised of 50 obese (body mass index > 30 kg/m2) adults. A total of 105 individuals were screened for eligibility and 50 participants were enrolled in the EMA protocol. Of these 50 participants, 9 participants met current criteria for full DSM-IV or subthreshold binge eating disorder (BED). Additional information on this sample is available in Goldschmidt et al. [19] and Berg et al. [20].

Measures

Each of the three studies from which the current samples were drawn assessed a variety of behavioral and affective constructs, many of which are not reported here. Analyses were limited to the following assessments for several reasons, including (a) availability of these measures across multiple samples, and (b) conceptual and clinical relevance to eating disorder psychopathology.

Diagnostic Interview

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P [21]) is a semi-structured interview that assesses Axis I psychiatric disorders. The SCID-I/P was used to determine DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for AN and BN in the first two samples, as well as for BED in the third sample.

Depression Symptoms (Retrospective Measure)

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI [21]) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that assesses symptoms of depression. The psychometric properties of the BDI have been well established [23]. Alpha coefficients for the BDI ranged from .91 to .94 across the 3 samples in this investigation.

Negative Affect (EMA Measure)

Items from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS [24]) were used to assess momentary negative affect in all three samples. A total of 8 negative affect items (nervous, angry at self, afraid, sad, disgusted, distressed, ashamed, and dissatisfied with self) were used in the AN sample, and 11 negative affect items (afraid, lonely, irritable, ashamed, disgusted, nervous, dissatisfied with self, jittery, sad, distressed, angry with self) were used in the BN and obesity samples. PANAS negative affect items were selected for each study based on high factor loadings and theoretical relevance to the specific population under investigation. Eight items were shared across all three studies, and three additional items were included in the BN and obesity samples. Participants rated their current mood for each of these items on a 5-point scale ranging from (1) not at all to (5) extremely. Alpha coefficients for negative affect ranged from .91 to .94 across the 3 samples in this investigation.

Eating Disorder Symptoms (Retrospective Measure)

The Eating Disorders Examination (EDE [3]) is a semi-structured interview used to assess the core aspects of eating disorder psychopathology. The EDE provides a global scale and four subscales (restraint, eating concern, shape concern, and weight concern), as well as frequency measures of binge eating and compensatory behaviors. The Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q [25]) is a self-report measure that provides the same subscales and behavioral frequencies as the interview-based EDE upon which it is based. The EDE was used in the AN and BN sample, whereas the EDE-Q was used in the OB sample. The validity and reliability of both the EDE and EDE-Q have been well documented [3, 26–27]. To simplify the discussion of the concordance between EMA and retrospective measures of eating disorder behaviors, we use the term EDE in subsequent sections to refer to the retrospective measure of eating disorder behaviors, which includes both the interview EDE (used in the AN and BN samples) and the EDE-Q (used in the OB sample).

Eating Disorder Symptoms (EMA Measure)

In all three studies, participants were asked to report on binge eating episodes. In the studies with the AN and BN samples, participants were instructed to provide an EMA rating when they experienced a binge eating episode. In the study with the obesity sample, participants provided dimensional ratings of both overeating and loss of control for each eating episode, which were used to define binge eating episodes (i.e., those episodes characterized by a 3 or higher on a 1 to 5 Likert-type scale for both dimensions were defined as a binge eating episode). In the AN and BN samples, participants were also asked to report on the occurrence of other eating disorder behaviors, including self-induced vomiting, laxative use, and exercise. Additional details regarding the EMA assessments for each sample are available in Engel et al. [15], Smyth et al. [14], and Goldschmidt et al. [19].

Procedures

Participants in all three samples were recruited from a variety of clinical, community, and academic settings. Approval for each study was obtained from the relevant institutional review boards at each site. Potential participants were initially screened via phone, following which eligible individuals attended an informational meeting where they received further information regarding the studies and provided written informed consent. Participants were then scheduled for assessment visits during which structured interviews were conducted and self-report questionnaires were administered.

A similar EMA protocol was used across all three studies. For each study, participants were trained on the use of palmtop computers and completed several practice days of recording prior to commencing the two-week EMA protocol. The EMA assessment schedule for all three studies included three types of daily self-report methods [28]: signal-contingent (i.e., ratings were provided in response to six semi-random signals throughout the waking hours of the day), event-contingent (i.e., participants were asked to record the occurrence of binge eating and certain other eating disorder behaviors), and interval-contingent (i.e., participants were asked to complete EMA ratings at the end of each day). Participants were compensated for completing the EMA assessments and received a bonus for excellent compliance rates.

Statistical Analyses

Given that several of the variables under investigation were not normally distributed, Spearman rho correlations were calculated to examine the association between the retrospective versus EMA measures of each affective or behavioral variable in each of the three studies. Specifically, these included associations between: (a) the BDI and EMA negative affect (calculated as the average of all negative affect ratings provided by each participant); (b) EDE frequency of binge eating and EMA frequency of binge eating; (c) EDE frequency of self-induced vomiting and EMA frequency of self-induced vomiting; (d) EDE frequency of laxative use and EMA frequency of laxative use; and (e) EDE frequency of exercise and EMA frequency of exercise. For eating disorder behavior frequency variables, data are presented as the average number of each respective behavior per week. Further, Bland-Altman plots were created to provide additional information regarding concordance between the measures of eating disorder behavior frequencies. These plots display the difference between behavioral frequencies as assessed via EMA versus EDE as a function of the average behavioral frequency across the two methods. Of note, the time frame for the eating disorder behaviors for the two assessment approaches did not overlap. Specifically, the EDE assessed frequency of behaviors over the previous 28 days, whereas the EMA approach measured the frequency of behaviors during the two-week EMA protocol, which was subsequent to the 28 day period assessed via the EDE.

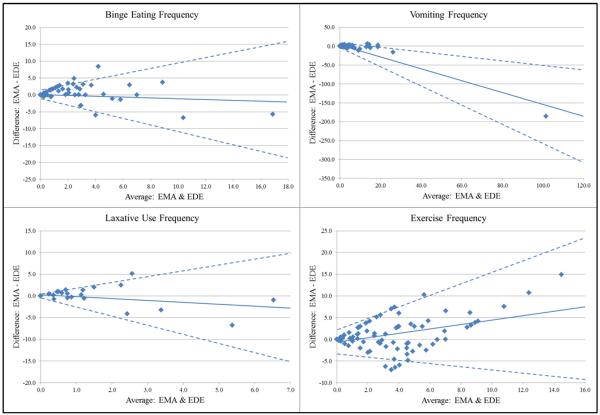

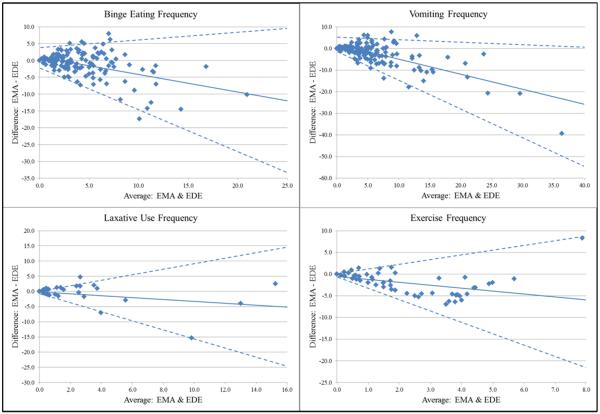

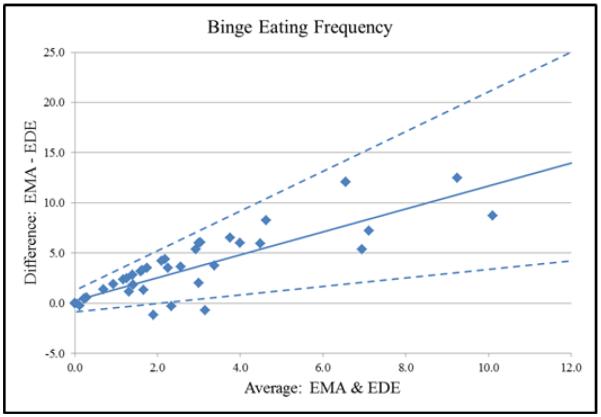

RESULTS

Correlational results are presented in Table 2. Across all three studies, correlations between the retrospective measure of depressive symptoms/negative affect (BDI) and the EMA measure of negative affect (average of all momentary PANAS ratings) were large, ranging from 0.495 to 0.783 (ps <0.0001). With regard to the associations for the various eating disorder behavior frequencies, correlations between frequencies obtained via the two assessment approaches were generally high, with some variation across different behaviors. Correlations ranged from .484 to .608 (ps <0.0001) for the frequency of binge eating, and correlations were .534 and .574 for the frequency of exercise (ps <0.0001). The two approaches for assessing purging behaviors were somewhat more strongly associated, with correlations of .661 and .873 (ps< 0.0001) for self-induced vomiting frequency and correlations of .678 and .745 for laxative use frequency (ps< 0.0001). Finally, Bland-Altman plots for each eating disorder behavior are presented in Figures 1 (AN sample), 2 (BN sample), and 3 (OB sample). Taken together, the plots suggest overall good agreement between the EMA and EDE assessments of eating disorder behavior frequencies, with a general pattern emerging in which the EDE provided somewhat higher estimates than EMA at higher average behavioral frequencies. Two exceptions to this pattern were found for binge eating frequencies in the OB sample and exercise frequencies in the AN sample, in which there was a pattern for somewhat higher estimates via EMA versus EDE.

Table 2.

Spearman Rho Correlations between EMA and Retrospective Measures of Negative Affect and Eating Disorder Behaviors

| Negative Affect | BDI vs. PANAS | Spearman Rho | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AN | .495 | 118 | ||

| BN | .553 | 133 | ||

| Obesity | .783 | 50 | ||

|

| ||||

| Eating Disorder Behavior | ||||

| AN | ||||

| Binges/week | .608 | 117 | ||

| Laxative use/week | .745 | 118 | ||

| Vomiting/week | .873 | 118 | ||

| Exercise/week | .574 | 118 | ||

| BN | ||||

| Binges/week | .484 | 129 | ||

| Laxative use/week | .678 | 132 | ||

| Vomiting/week | .661 | 130 | ||

| Exercise/week | .534 | 133 | ||

| Obesity | ||||

| Binges/week | .568 | 50 | ||

Note. The n varies slightly for each correlation due to missing cases. All correlations p < 0.0001

Figure 1.

Bland-Altman Plots for Eating Disorder Behavior Frequencies in the AN Sample. The solid line in each plot represents the average discrepancy between EMA and EDE across behavioral frequencies, and the dashed lines represents the 95% confidence intervals for the average discrepancy.

Figure 2.

Bland-Altman Plots for Eating Disorder Behavior Frequencies in the BN Sample. The solid line in each plot represents the average discrepancy between EMA and EDE across behavioral frequencies, and the dashed lines represents the 95% confidence intervals for the average discrepancy.

Figure 3.

Bland-Altman Plots for Binge Eating Frequency in the OB Sample. The solid line represents the average discrepancy between EMA and EDE binge eating frequencies, and the dashed lines represents the 95% confidence intervals for the average discrepancy.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to examine the extent to which EMA and retrospective measures of eating disorder behaviors and negative affect were concordant using data from three distinct clinical samples of individuals with AN, BN, or OB. Taken together, the results reflected moderate to strong correlations for both negative affect and eating disorder behaviors, suggesting that these distinct assessment approaches are concordant for the variables assessed in this study. Interestingly, the two purging behaviors were characterized by strong evidence of convergence, while the evidence for binge eating and exercise was more moderate across the samples. This finding is consistent with other studies which have found stronger concordance across assessment formats when assessing frequency of purging behaviors versus binge eating (see Berg et al. [1]). Further, of particular note, the timeframe for the eating disorder behaviors differed for the two assessments; thus, the apparent concordance between the two assessment methods is suggestive of at least moderate consistency in the frequency of eating disorder behaviors over time in these samples. The relative stability of these behavioral parameters further suggests that assessing the frequency of such behaviors in the more recent past may be sufficient to establish an overall pattern of behavior, in contrast to assessments requiring individuals to recall their behaviors across more distant timeframes.

Retrospective questionnaires and interviews such as the BDI and the EDE have a wealth of empirical support in terms of reliability and validity [e.g., 23, 27], and have been widely used in eating disorders research. However, a limitation of such measures is that they are not well-suited for study designs requiring repeated, momentary assessments. Such study designs provide the opportunity to capture dynamic relationships between constructs such as affect and behavior over shorter timeframes that cannot be adequately captured with traditional forms of assessment. Several recent EMA studies have demonstrated that changes in negative affective states are significant predictors of eating disorder behaviors over short time frames [14–15, 29]. In light of the moderate correlations found for the negative affect measures across the two assessment approaches in this investigation, these current findings support the premise that the association between affect and eating disorder behaviors that has been identified in momentary studies may be tapping similar underlying processes as those that have been identified in studies using more traditional retrospective forms of assessment over longer timeframes.

Although moderate to strong convergence of the measures in the present study were found, there are data to suggest that associations between affect and eating disorder behaviors differ based upon the assessment formats used to assess the constructs. For example, in a sample of women with AN, Lavender et al. [30] showed a stronger association between eating disorder psychopathology and affective lability as assessed via EMA versus a traditional self-report questionnaire, although this finding did not hold for a measure of affective intensity (i.e., average levels of anxiety). Similarly, in a sample of women with BN, Anestis et al. [31] found that an EMA measure of affective lability was more strongly associated with binge eating frequency than a traditional self-report measure of affective lability, although associations with overall eating disorder psychopathology did not differ. Thus, although the current findings provide evidence supporting some degree of convergence between the EMA and retrospective measures of negative affect and eating disorder behaviors, meaningful differences between the assessment strategies may still be present.

Certain limitations of this investigation should be noted. Because our samples were comprised primarily of Caucasian women, the lack of diversity leaves the generalizability of the results to more diverse samples unclear. Also, it should be noted that both EMA and traditional measures rely, to some extent, on retrospective recall and participants' willingness to divulge information, which is a limitation of both approaches. Another limitation is that the specific measures used in the retrospective assessment and EMA were not identical as the BDI examines trait level depressive symptoms, while the PANAS captures momentary mood states via EMA. Thus, these results represent the convergence of highly related, but not identical constructs. Additionally, the method by which the EMA negative affect variable was calculated (i.e., via aggregation of all EMA negative affect ratings for a given participant) could have introduced additional error that impacted the results [32]. However, in the present study, this procedure was thought to provide the best approach to deriving an appropriate measure for comparison to retrospective assessments. Finally, EMA data were only collected during a period after participants completed the retrospective measures. As such, the timeframe on which the assessments were based did not overlap. However, the findings of at least moderate convergence, given the absence of temporal overlap, may speak to a fairly robust association between these measurement strategies.

Despite the limitations noted above, these preliminary findings support the convergence of data on affect and eating disorder behaviors gathered through two distinct assessment methodologies, which is important in terms of comparing and synthesizing research findings across studies that use these differing approaches to assessment. EMA provides certain benefits over traditional retrospective measures that typically rely on retrospective recall and global perceptions of a given construct (e.g., how anxious or depressed one typically is), and provides the ability to examine temporal associations between variables in a more momentary fashion (e.g., negative affect prior to and following binge eating). However, EMA is inherently more burdensome compared to most traditional retrospective measures. The present findings suggest that for certain constructs, including the frequency of certain eating disorder symptoms and overall levels of negative affect/depressive symptomatology, there is moderate to strong concordance across assessment formats. Thus, given that each of these assessment approaches have their own advantages and disadvantages, decisions to use one method versus another should be guided by the specific research questions under investigation and related research considerations (e.g., EMA may be less feasible in studies which require very large samples, but would likely be preferable in research examining momentary antecedents and/or consequences of particular behaviors).

References

- [1].Berg KC, Peterson CB, Frazier P, Crow SJ. Convergence of scores on the interview and questionnaire versions of the Eating Disorder Examination: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Assess. 2011;23:714–724. doi: 10.1037/a0023246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Smyth J, Wonderlich S, Crosby R, Miltenberger R, Mitchell J, Rorty M. The use of ecological momentary assessment approaches in eating disorder research. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;30:83–95. doi: 10.1002/eat.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment. Guilford; New York: 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fichter MM, Elton M, Engel K, Meyer AE, Mal H, Poustka F. Structured interview for anorexia and bulimia nervosa (SIAB): Development of a new instrument for the assessment of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 1991;10:571–592. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Glasofer DR, Sysko R, Attia E, Crosby RD, Hildebrandt T, Mitchell JE, et al. Eating disorder assessment for DSM-5: A structured clinical interview for DSM-5 eating disorders. Paper presented at the meeting of the Eating Disorder Research Society; Porto, Portugal. Sep, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Stice E, Telch CF, Rizvi SL. Development and validation of the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale: A brief self-report measure of anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder. Psychol Assess. 2000;12:123–131. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Forbush KT, Wildes JE, Pollack LO, Dunbar D, Luo J, Patterson K, et al. Development and validation of the eating pathology symptoms inventory (EPSI) Psychol Assess. 2013;25:859–878. doi: 10.1037/a0032639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Keel PK, Crow S, Davis TL, Mitchell JE. Assessment of eating disorders: Comparison of interview and questionnaire data from a long-term follow-up study of bulimia nervosa. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:1043–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Stone AA, Shiffman S. Ecological Momentary Assessment in behavioral medicine. Ann Behav Med. 1994;16:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Stone AA, Schwartz JE, Neale JM, Shiffman S, Marco CA, Hickcox M, et al. A comparison of coping assessed by ecological momentary assessment and retrospective recall. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74:1670–1680. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychol Assess. 2009;21:486–497. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bruehl S1, Liu X, Burns JW, Chont M, Jamison RN. Associations between daily chronic pain intensity, daily anger expression, and trait anger expressiveness: an ecological momentary assessment study. Pain. 2012;153:2352–2358. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Smyth J, Wonderlich SA, Heron K, Sliwinski M, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, et al. Daily and momentary mood and stress predict binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Peterson CB, et al. The role of affect in the maintenance of anorexia nervosa: evidence from a naturalistic assessment of momentary behaviors and emotion. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:709–719. doi: 10.1037/a0034010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Goldschmidt AB, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Peterson CB, Le Grange D, et al. Momentary affect surrounding loss of control and overeating in obese adults with and without binge eating disorder. Obesity. 2012;20:1206–1211. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edition. APA; Washington, DC: 2000. test revision (DSM-IV-TR) [Google Scholar]

- [18].Le Grange D, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Cao L, Ndungu A, Crow SJ, et al. DSM-IV-defined anorexia nervosa versus subthreshold anorexia nervosa (EDNOS-AN) Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2013;21:1–7. doi: 10.1002/erv.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Goldschmidt AB, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Crow SJ, Cao L, Peterson CB, et al. Affect and eating behavior in obese adults with and without elevated depression symptoms. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:281–286. doi: 10.1002/eat.22188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Berg KC, Peterson CB, Crosby RD, Cao L, Crow SJ, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA. Relationship between daily affect and overeating-only, loss of control eating-only, and binge eating episodes in obese adults. Psychiatry Res. 2014;215:185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders: Patient Edition (SCID I/P) Biometrics; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Berg KC, Peterson CB, Frazier P, Crow SJ. Psychometric evaluation of the eating disorder examination and eating disorder examination-questionnaire: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:428–438. doi: 10.1002/eat.20931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wheeler L, Reis HT. Self-recording of everyday life events: Origins, types, and uses. J Pers. 1991;59:339–354. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Berg KC, Crosby RD, Peterson CB, Engel SE, Mitchell JE, Wonderlich SA. Facets of negative affect prior to and following binge-only, purge-only, and binge/purge events in women with bulimia nervosa. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:111–118. doi: 10.1037/a0029703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lavender JM, De Young KP, Anestis MD, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Engel SG, et al. Associations between retrospective versus ecological momentary assessment measures of emotion and eating disorder symptoms in anorexia nervosa. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:1514–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Anestis MD, Selby EA, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Joiner TE. A comparison of retrospective self-report versus ecological momentary assessment measures of affective lability in the examination of its relationship with bulimic symptomatology. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Watson D, Tellegen A. Aggregation, acquiescence, and the assessment of trait affectivity. Journal of Research in Personality. 2002;36:589–597. [Google Scholar]