Abstract

Purpose

To examine the prospective association between healthy lifestyle behaviors and objectively measured physical function in midlife women.

Methods

Participants included 1,769 racially/ethnically diverse women, ages 56-68, from the SWAN (Study of Women's Health Across the Nation) cohort. Physical function was assessed at the 13th follow-up (FU13) visit with the Short Physical Performance Battery (4 meter walk, repeated chair stands, and balance test) and grip strength. A Healthy Lifestyle Score (HLS), which ranged from 0-6, was calculated by averaging as many as three repeated measures of self-reported smoking, physical activity, and diet, all assessed prior to FU13. Multivariable linear and logistic regressions modeled each component of physical performance as a function of HLS and, in separate models, of each lifestyle behavior, adjusted for the other behaviors.

Results

In multivariable analyses, the time for the 4 M walk was 0.06 secs faster (p=0.001) for every 1 point increase in the HLS. The time for the repeated chair stands was significantly shorter by about 0.20 seconds. Neither grip strength nor balance problems were significantly associated with the HLS (p=.28, p=0.19 respectively). The model examining the individual health behaviors showed that only physical activity was significantly associated with physical performance.

Conclusion

Regular physical activity in early midlife has the potential to reduce the likelihood of physical functional limitations later in midlife.

Keywords: physical activity, diet, smoking, grip strength, balance, mobility, prospective cohort

Introduction

Decrements in physical function are the first stage in the disablement process which extends through functional limitations to disability, frailty, and finally death[41]. Although the prevalence of functional limitations increases with age[24], the disablement process begins in midlife. In the National Health Interview Survey, 15% of respondents ages 45-64, had some functional limitations or disability, with half of those reporting that the limitation or disability first developed between the ages of 40 and 55[1]. In the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN), 29.6% of the cohort, ages 45-57, reported moderate functional limitations and 11.0% reported severe limitations[38].

However, the disablement process is neither inevitable or irreversible[41, 45]; many factors contribute to the transition of a functional impairment into a functional limitation. Given the individual and societal burden of disability, particularly at more advanced ages [11], identifying modifiable factors that can slow, stop, or even reverse, the disablement process at the early stages in midlife is a significant clinical and public health issue.

A number of investigations in older populations suggest the same healthy lifestyle factors that reduce risk of morbidity and mortality (e.g. being physically active, having a healthy diet, and not smoking), also reduce the likelihood of functional limitations and disability[8, 19, 22, 25, 27, 29, 30, 32, 33, 42, 44]. For example, in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I and Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study, increased recreational physical activity (PA) over a period of 10 years resulted in reduced risk of disability, whereas reduced PA increased the risk[14]. Similarly, in a combined analysis of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and the Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) cohorts, current smoking was strongly related to impaired mobility[29], and in the Health ABC cohort, adherence to a Mediterranean diet was associated with less decline in walking speeds over 8 years[32]. Analyses that combine these behaviors into composite measures also show reduced risk of mobility limitation over time[10, 25].

To date, most of this literature is based on older [19, 25, 44], predominantly white populations[8, 29, 32, 42], focused on single health behaviors[8, 14, 22, 32, 42, 44] and/or reliant on self-reported measures of mostly mobility-related physical function, rather than objectively measured physical performance that includes more integrated measures of function[14, 19, 21, 25, 29]. The aim of the current study is to examine the individual and combined influence of participation in regular physical activity, consumption of a healthy diet, and abstinence from tobacco on subsequent performance-based measures of physical function during midlife, using data from the Study of Women Across the Nation (SWAN). The degree to which these relations vary by obesity status or race/ethnicity are also examined.

Methods

Study Population

The sample for this analysis was drawn from the 1,945 women in the SWAN cohort who had at least one measure of physical performance during the Year 13 follow-up exam (FU13) conducted in 2012. The SWAN cohort, which consisted of 3,302 initially pre- and early-peri menopausal women of diverse race/ethnicities, was formed in 1996-97 to study the natural history of the menopausal transition. Details of the sampling and recruitment strategies have been previously described[34]. Briefly, women, ages 42-52, were recruited from defined sampling frames in seven geographic sites across the United States: Boston, Chicago, Detroit area, Los Angeles, Newark, NJ, Oakland, CA, and Pittsburgh. To be eligible, women had to report having had a menstrual period and no use of exogeneous hormones in the 3 months prior to recruitment, not be pregnant or lactating, and to identify their primary race/ethnicity as black(Boston, Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh), Japanese (Los Angeles), Hispanic (Newark), Chinese (Oakland), or white (all sites). The cohort participated in a baseline clinical examination and continues to be seen for annual or bi-annual exams. Retention at FU13 was 77%. All participants provided written informed consent, and all protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions.

Excluded from this analysis were 136 women who reported substantial functional limitation at baseline on any item on the physical functioning subscale of the MOS-SF-3[43], 3 women with unknown baseline physical functional status, and 17 women who had not reached menopause by the Year 13 visit. An additional 20 women were excluded because of incomplete exposure data. The primary analysis is based on the remaining 1,769 participants. In comparison to those who were included, women who were excluded were more likely to be black or Hispanic, current smokers, and obese, and to have less education, more difficulty paying for basics, more depressive symptoms, and poorer health status.

Assessment of Healthy Lifestyle

Three health behaviors, dietary intake, smoking and physical activity, were assessed as components of a healthy lifestyle. All three were measured by self-report at baseline (BL) (1996/7), FU05 (2001/02) and FU09 (2005/6). As explained in detail below, each behavior at each visit was assigned a value of 0, 1, or 2, based on specific criteria for that behavior.

Diet

Dietary intake was assessed with the 1995 Block Food Frequency questionnaire (FFQ) adapated for SWAN by the addition of foods frequently consumed by the populations represented in the SWAN cohort (Hispanic, Chinese and Japanese)[7, 23]. The FFQ, which asks about usual dietary intake during the past year, was administered by trained and certified interviewers in English, Spanish, Chinese and Japanese using food models to help respondents estimate portion size. Details about the development and validity of the Block FFQ have been well described elsewhere [5, 6].

A healthy diet score was created based on the recommendations of the Healthy Eating Index [15] and the availability of the relevant food items in the SWAN FFQ, and included 8 components: fiber, sodium, trans fat, fatty acids, fruits and vegetables, dairy, grains and added sugar. Healthy eating behavior in each of these components was defined as follows: daily intake of fiber ≥ 25 grams, sodium ≤1.1gm/1,000 kcals, trans fat <1% kcals, ratio of poly+mono unsaturated fats (gm) to saturated fats (gm) >2.5., fruits and vegetables ≥ 5 servings, diary ≥1.3 cups/1,000kcals, grains ≥ 3 oz/1,000 kcals, and added sugar <2.5% total kcals. One point was assigned to each of these healthy eating behaviors that were present in a participant's reported diet and then summed over all components for a diet score that could range from 0-8. Based on the distribution, a score of 2 was given when two or more components were present (fewer than 13% met the criteria for more than two components), a score of 1 if only one component was present, and a score of 0 if none were present.

Smoking

Standardized questions from the American Thoracic Association[12] were used to assess smoking behavior at each visit; never smoking was given a score of 2, former smoking a score of 1, and current smoking a score of 0.

Physical Activity

Physical activity was assessed from the sports and exercise questions on the widely used and validated Kaiser Physical Activity Survey[2, 35]. Questions related to duration, frequency, and perceived intensity were used to determine whether women met current physical activity recommendations (moderate-vigorous activity for at least 150 minutes/week)[39]. Those who reported at least 2 hrs/wk of sports/exercise for at least 9 months of the year with at least a moderate increase in heart rate and breathing were classified as meeting those recommendations and given a score of 2. A score of 1 was given to women who played sports or exercised more than once a month but less than twice a week, and a score of 0 for women who did sports or exercise no more than once a month,

Healthy Lifestyle Scores (HLS)

To create an overall healthy lifestyle score for each visit, the scores for diet, smoking and physical activity were summed, yielding a visit-specific HLS with a possible range of 0 to 6. The visit-specific scores were then averaged over all non-missing visits to create an average HLS, also with a possible range of 0-6. The continuous average HLS was used as the primary exposure variable in the multivariable analyses; it was also categorized as a 3-level variable: unhealthy=0-<3, moderately healthy=3-4, and healthy>4, based on approximate quartile cut-points (lower quartile, middle two quartiles, and upper quartile) for ease of presentation of descriptive data and in secondary analyses.

Component Scores

The visit-specific scores for each of the behaviors included in the HLS were also averaged across all non-missing visits to give average component scores for diet, smoking and physical activity for use as exposure variables in secondary analyses.

Measures of Physical Performance

Participants completed a range of physical performance tests at the Year 13 follow-up exam, all conducted by trained and certified staff following a standard SWAN protocol. The results of these tests were summarized into five outcome variables as described below.

Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB)

The SPPB consists of two mobility- and lower body strength measures (timed 4 M walk at usual pace, chair stand with five repetitions) and a series of balance tasks (side-by-side, semi-tandem, tandem, and one foot stands, each held for 10 seconds), following the standard protocol[18]. The SPPB was originally developed for the Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly (EPESE), and has well-established reliability and validity as a measure of lower extremity function necessary for daily activities[18]. The total SPPB score ranges from 0 (worst performance) to 12 (best performance). Given the younger age distribution of the SWAN cohort, relative to the age range for which the SPPB was developed, the distribution of the total SPPB score in SWAN was skewed to the right (mean=10.79, sd=1.66, median=11.0, I-Q range=10-12), with almost half (46.7%) having a perfect score of 12 and fewer than 17% scoring below 10, a cut-point for risk of disability. As a result, for this analysis, the total SPPB was not examined as an outcome, but, rather, each of the SPPB components was considered separately: the minimum time in seconds from two attempts at the 4 meter walk, the time in seconds to sit and stand five times, and the successful completion of all four balance stand tasks (yes vs. no).

Grip Strength

A Baseline® hydraulic dynamometer adjusted for hand size was used to assess grip strength in the dominant hand, following a standardized protocol with the participant seated with her arm bent at a 90 degree angle at the elbow. The maximum (kg) of three attempts was used as an outcome variable.

Decile Score

Because the total SPPB score produced so little variability in physical performance among the SWAN cohort and could not be used as a continuous outcome, given its skewness, a summary decile score was created following the procedure developed by Michael et al [28]. This score ranked participants by decile (1-10), based on their performance in the4 M walk, grip strength and chair stand, and was created by summing the sample-specific decile for each of the tests, producing a score with a range of 3-30. For example, a participant in the bottom decile of the cohort for all 3 components would have a decile score of 3 while a participant in the top decile for the 3 tasks would have a decile score of 30.

Covariates

Body mass index (BMI) at both BL and FU13 was calculated as kg/(meters)2 from measured height and weight, using a calibrated scale and stadiometer, and categorized into ethnic-specific under- or normal weight, overweight and obese (<25 for Caucasian, Hispanic and black women and <24 for Chinese and Japanese women, 25(or 24)-<30, >30)[36]. All other covariates were self-reported. Those assessed only at BL included race/ethnicity (black, Chinese, Hispanic, Japanese, or white) and education (high school or less, some college or college degree and higher). Age in years, marital status (single/never married, married/living as married, and separated/widowed/divorced), difficulty paying for basics (somewhat/very hard, not hard), alcohol consumption (≥1/mo., >1/mo but<2/wk, ≥2/wk), menopausal status (pre, early peri at baseline and surgical post, natural post at FU13), overall health (exercellent/very good, good, or fair/poor), and presence of depressive symptoms, defined by a score of ≥16 on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale [31] were assessed at both BL and FU13. A diagnosis of diabetes or osteoarthritis, ever use of hormone therapy, and number of comorbidities (0,1, ≥2) among cancer, high blood pressure, stroke, heart attack, osteoporosis was considered present at FU13 if reported at any time from BL through FU13. Potential site or participant variability related to the physical performance test protocol, such as floor surface and foot covering, as well as clinical site, were also examined for confounding. All covariates were selected based on the literature and biological plausibility for confounding the main relations of interest.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of the study population at FU13 by category of average HLS (unhealthy, moderately healthy, and healthy) were described by means and standard deviations (sd) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables and compared with ANOVA or Chi square tests, as appropriate. The mean (sd) differences or differences in proportions in each of the performance measures across the categories of average HLS were evaluated with ANOVA.

Linear regression analyses were used to model each continuous physical performance measure as a function of the continuous average healthy lifestyle score, adjusted for FU13 (or baseline if only assessed at baseline) confounders while multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to estimate the risk of balance problems. With the continuous average HLS as the independent variable, models were run for each performance measure outcome, proceeding, first, from unadjusted models, to a minimally adjusted model that included age, number of non-missing visits, race/ethnicity, BMI, overall self-rated health and clinical site, and then adding sequentially: a) outcome-specific quality measures (i.e. floor surface, dynamometer setting);b) demographic variables (education, marital status and difficulty paying for basics); and c) medical/health indicators. Final models were derived by starting with the fully adjusted model, removing the covariate with the largest p-value greater than 0.1, examining the effect estimates on the independent measure of interest, then refitting the model without the covariate to identify the next covariate with a p-value >0.1 and so on, until all remaining covariates, except for those in the minimally adjusted model, had a p<0.1. This strategy has been demonstrated to yield the most parsimonious model while still accounting for all confounding variables [20, 26]). For those covariates assessed at both baseline and FU13, the FU13 value was used in these models. Effect modification by FU13 BMI and race/ethnicity was examined by entering appropriate cross-product terms into the final model for each performance measure; models were stratified if the interaction term had a p value ≤0.10. The same modeling strategy was followed to examine each performance measure as a function of each continuous average component score, adjusted for the other behaviors, and expressed in units of standard deviations to allow for comparison of the magnitude of associations across the three behaviors.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to ensure the robustness of the findings by 1) substitution of average HLS as a categorical variable for the continuous variable; 2) adjustment for baseline characteristics rather than Year 13 characteristics; 3) adjustment for Year 13 physical activity; 4) inclusion only of women with exposure data from all 3 time points (baseline, Years 5 and 9); 5) inclusion only of women who reported no functional limitation at baseline on the SF36 Physical [37]; 6) substitution of visit-specific healthy lifestyle and component scores for average HLS or component scores; and 7) “age-standardized” models to eliminate the variability in the outcome attributable to age by using the residual of age regressed against the performance outcome as an independent variable. Results from these analyses are not reported below since they were all consistent with the primary analyses.

All analyses were conducted in SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA)

Results

In the sample as a whole, the average Healthy Lifestyle Score was reasonably normally distributed, with a mean=3.4 (sd=1.2); 26.3% of the sample had an unhealthy HLS (0=<3), 47.1% had a moderately healthy HLS (3-≤4), and 26.6% had a healthy HLS (>4). Sixty two percent, 25% and 46% of the sample had average smoking, physical activity, or diet scores respectively greater than 1.

As Table 1 shows, the mean age of the cohort at FU13, when physical performance was measured, was 61.9 years (sd=2.7 and range 56-68) with women who had an unhealthy HLS being slightly, but significantly, younger. Black and Hispanic women were more likely to have an unhealthy HLS, while Chinese and Japanese were less likely. Other characteristics associated with an unhealthy HLS were education less than a college degree, obesity, not being married, having difficulty paying for basics, reporting less than excellent or very good overall health, having depressive symptoms, ever being diagnosed with diabetes or osteoarthritis, and having 1 or more co-morbidities. A similar pattern was observed for the association between baseline characteristics and HLS (data not shown).

Table 1. Characteristics of study sample at visit 13 by category1 of average healthy lifestyle score.

| Healthy Lifestyle Score (HLS) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total2 | Unhealthy | Mod Healthy | Healthy | p value | |

| N (%) | 1769 | 466 (26.3) | 833 (47.1) | 470 (26.6) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 61.9 (2.7) | 61.5 (2.6) | 62 (2.7) | 62.1 (2.7) | 0.001 |

| Ethnicity, n (%)1 | |||||

| Black | 465 (26.3) | 170 (36.5) | 224 (26.9) | 71 (15.1) | <0.0001 |

| Caucasian | 857 (48.4) | 217 (46.6) | 402 (48.3) | 238 (50.6) | |

| Chinese | 180 (10.2) | 6 (1.3) | 79 (9.5) | 95 (20.2) | |

| Hispanic | 84 (4.7) | 36 (7.7) | 46 (5.5) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Japanese | 183 (10.3) | 37 (7.9) | 82 (9.8) | 64 (13.6) | |

| Education, n (%)1 | |||||

| ≤ High school | 344 (19.6) | 133 (28.7) | 148 (17.9) | 63 (13.5) | <0.0001 |

| Some college | 560 (31.9) | 165 (35.6) | 284 (34.3) | 111 (23.8) | |

| College degree / post-college | 853 (48.5) | 165 (35.6) | 396 (47.8) | 292 (62.7) | |

| BMI category, n (%) | |||||

| Underweight / Normal | 522 (29.7) | 94 (20.3) | 214 (25.8) | 214 (45.6) | <0.0001 |

| Overweight | 537 (30.5) | 141 (30.5) | 260 (31.4) | 136 (29) | |

| Obese | 701 (39.8) | 227 (49.1) | 355 (42.8) | 119 (25.4) | |

| Smoking, n (%) | |||||

| Never smoker | 1083 (61.8) | 83 (18) | 578 (70.1) | 422 (90.2) | <0.0001 |

| Former Smoker | 541 (30.9) | 265 (57.6) | 230 (27.9) | 46 (9.8) | |

| Current smoker | 129 (7.4) | 112 (24.3) | 17 (2.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Alcohol Use, n (%) | 0.1256 | ||||

| None or low (≤1/month) | 880 (50.2) | 219 (47.5) | 437 (53.1) | 224 (48.1) | |

| Moderate (>1/month, <2/week) | 445 (25.4) | 127 (27.5) | 204 (24.8) | 114 (24.4) | |

| High (≥2/week) | 425 (24.2) | 115 (24.9) | 182 (22.1) | 128 (27.5) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||||

| Single/never married | 208 (11.8) | 64 (13.7) | 104 (12.5) | 40 (8.5) | <0.0001 |

| Married | 1073 (60.7) | 235 (50.4) | 501 (60.1) | 337 (71.7) | |

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 488 (27.6) | 167 (35.8) | 228 (27.4) | 93 (19.8) | |

| Somewhat/very hard to pay for basics, n (%) | 439 (25.5) | 169 (37.2) | 204 (25.2) | 66 (14.4) | <0.0001 |

| Overall health, n (%) | |||||

| Excellent/Very good | 902 (51.5) | 170 (37) | 421 (51.1) | 311 (66.7) | <0.0001 |

| Good | 583 (33.3) | 185 (40.2) | 286 (34.7) | 112 (24) | |

| Fair/Poor | 265 (15.1) | 105 (22.8) | 117 (14.2) | 43 (9.2) | |

| Menopausal status, n (%) | |||||

| Surgical post-menopause | 190 (10.7) | 52 (11.2) | 95 (11.4) | 43 (9.1) | 0.43 |

| Natural post-menopause | 1579 (89.3) | 414 (88.8) | 738 (88.6) | 427 (90.9) | |

| Hormone use (ever), n (%) | 767 (43.4) | 194 (41.6) | 362 (43.5) | 211 (44.9) | 0.60 |

| CES-D ≥16, n (%) | 226 (12.8) | 88 (18.9) | 107 (12.8) | 31 (6.6) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes (ever), n (%) | 314 (17.8) | 112 (24) | 158 (19) | 44 (9.4) | <0.0001 |

| Osteoarthritis (ever), n (%) | 995 (56.2) | 290 (62.2) | 488 (58.6) | 217 (46.2) | <0.0001 |

| No. of comorbidities, n (%) | |||||

| 0 | 661 (37.4) | 146 (31.3) | 308 (37) | 207 (44) | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 826 (46.7) | 243 (52.1) | 372 (44.7) | 211 (44.9) | |

| ≥2 | 282 (15.9) | 77 (16.5) | 153 (18.4) | 52 (11.1) | |

Unhealthy HLS=score of 0-<3, moderately healthy HLS=score of 3-<4, and healthy HLS=score of >4

Total percentages may not be equal to 100 due to rounding

Table 2 demonstrates that all of the physical performance measures were associated in a dose response relation with the categorized average HLS. For the 4 meter walk and chair stands performance was better (i.e., faster) with higher healthy lifestyle scores, with women in the healthy HLS category having 19-21% faster walking or sit-to-stand times than women in the unhealthy HLS category. Similarly, the decile score was almost 17% higher in those with a healthy HLS compared to those with an unhealthy HLS (p for trend 0.0001), and the proportion of women with balance problems was greatest in those in the unhealthy HLS category. In contrast, grip strength was inversely associated with HLS with women who were in the healthy HLS category having 4% lower grip strength compared to women in the unhealthy HLS category (p for trend <0.005).

Table 2. Mean (sd) of physical performance measures by category of average healthy lifestyle score.

| Physical Performance Measures | All (N=1769) | Unhealthy (n=466) | Mod. Healthy (n=833) | Healthy (n=470) | p for linear trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | ||

|

| |||||

| 4 M walk (sec) | 4.09 (1.13) | 4.38 (1.24) | 4.16 (1.13) | 3.68 (0.88) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Grip strength (kg) | 25.35 (5.66) | 25.83 (5.65) | 25.41 (5.75) | 24.79 (5.47) | 0.005 |

|

| |||||

| Chair stand (sec) | 11.14 (3.58) | 12.16 (3.88) | 11.21 (3.5) | 10.04 (3.11) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Physical performance decile score | 16.46 (5.73) | 15.14 (5.71) | 16.21 (5.69) | 18.16 (5.43) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Balance problem | 0.01 | ||||

| No | 1572 (90.0) | 401 (87.4) | 741 (90.1) | 430 (92.3) | |

| Yes | 174 (10.0) | 58 (12.6) | 80 (9.8) | 36 (7.7) | |

Note: The total sample size varied for each of the physical performance measures due to NJ and LA sites not participating in the 40 ft walk, exclusion of women needing assistance on either the 40 ft walk or the 4 M walk, or missing data; n for 40 ft walk = 1309, n for 4 M walk = 1728, n for grip strength = 1760, n for chair stand = 1714, n for decile score = 1707, n for balance problem = 1746

The bivariate associations between the categorized HLS and physical performance were mostly unchanged in the multivariable models that examined the continuous average HLS as the predictor variable and adjusted for multiple confounding variables (Table 3). In both minimally adjusted and final models, the time for the 4 M walk was 0.06 of a second faster for every 1 point increase in the average HLS (p=0.001). The time for the repeated chair stands was significantly shorter by about 0.20 seconds, and the decile score was significantly higher by about three tenths of a point. After adjustment for BMI and other confounders, the associations between HLS and both grip strength and balance problems were no longer statistically significant.

Table 3. Prospective1 association of continuous average healthy lifestyle score2 with physical performance measures, adjusted for confounders.

| Minimally Adjusted Model3 | Final Model4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Beta (95% CI) | p value | Beta (95% CI) | p value |

| 4 M Walk (sec) | -0.06 (-0.1, -0.03) | 0.0005 | -0.06 (-0.1, -0.02) | 0.001 |

| Grip strength (kg) | 0.14 (-0.09, 0.37) | 0.23 | 0.14 (-0.09, 0.37) | 0.24 |

| Chair stand (sec) | -0.21 (-0.34, -0.08) | 0.002 | -0.18 (-0.31, -0.05) | 0.008 |

| Decile Score | 0.44 (0.22, 0.65) | <0.0001 | 0.35 (0.13, 0.57) | 0.002 |

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

| No balance problem (vs. some) | 0.906 (0.78, 1.06) | 0.20 | 0.88 (0.76, 1.04) | 0.13 |

Healthy lifestyle score measured at least 4 years prior to physical performance measures

Possible range of healthy lifestyle score=1-6

Adjusted for age, race, site, BMI, overall self-rated health and number of visits with HLS

All models adjusted for age, race, site, BMI, overall self-rated health, and arthritis; 4 m walk additionally adjusted for number of comorbidities and foot covering; 40 ft walk additionally adjusted for marital status, diabetes, arthritis, type of menopause, floor surface and alcohol use; grip strength additionally adjusted for difficulty paying for basics, alcohol use, dominant hand and dynamometer setting; chair stand additionally adjusted for number of comorbidities, difficulty paying for basics, foot covering; decile score additionally adjusted for number of comorbidities, difficulty paying for basics, education, alcohol use, and arthritis; balance additionally adjusted for CES-D, foot covering, hormone use and alcohol use

Because obesity significantly modified the relation between the HLS and the 4 M walk (p for interaction = 0.03), models were stratified by BMI; the results suggested that the association between the HLS and the 4 M walk was statistically significant only in normal weight women (beta=-0.125, p<0.0001), and not in overweight (beta=-0.05, p=0.11) or obese women (beta=-0.024, p=0.47). Interaction terms between BMI and HLS were not statistically signficant for the other physical performance outcomes, nor were there any statistically signficant interactions with race/ethnicity although small numbers for some race/ethnic groups may have limited the ability to detect such interactions.

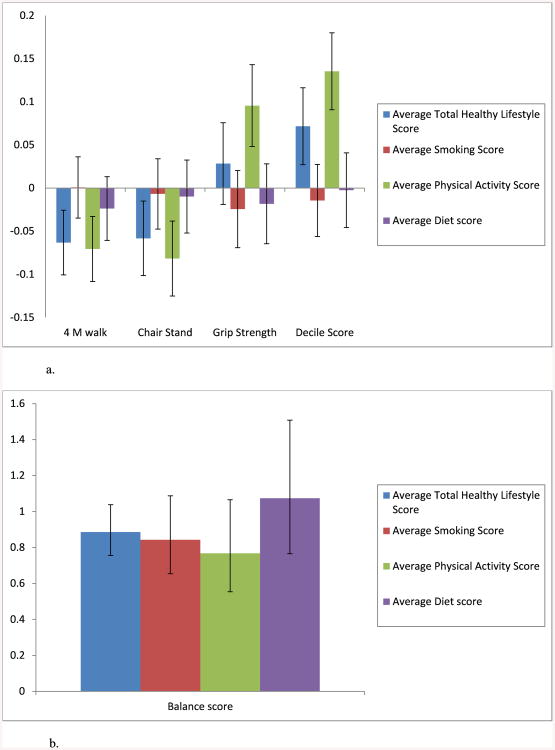

To explore the impact of individual health behaviors on physical performance, the continuous, average component scores, expressed in units of standard deviation, were examined as three independent variables in the same fully adjusted models with each performance variable as an outcome. As Figure 1 demonstrates, neither smoking behavior nor diet, averaged over earlier exams, was significantly associated with any of the physical performance measures at FU13. In contrast, greater physical activity was strongly associated with faster walking time, faster repeated sit to stand, stronger grip strength, and higher decile performance ranking. It was also associated with reduced risk of balance problems, although the association was not statistically significant.

Figure 1.

a. Multivariable prospectivea associations (standardized betas) between continuous physical performance measures and 1) total Healthy Lifestyle Scoreb and 2) each healthy lifestyle behaviorb adjusted for the other behaviors.

a. Healthy lifestyle behaviors measured at least 4 years prior to physical performance measures

b. Total healthy lifestyle score and each component score are treated as a continuous average over all available visits and ranges from 0-6 for total score and 0 to 2 for components scores; results are presented as the average increase in standard deviation of each outcome for one standard deviation of the total healthy lifestyle score or each of the behavior component scores.

Note: Results are from two separate linear regression models: one included the total healthy lifestyle score; the other included all three behavior component scores. Confounders included: for all models: age, race, site, BMI, overall self-rated health, and arthritis; for 4 m walk: number of comorbidities and foot covering; for 40 ft walk: marital status, CES-D, diabetes, type of menopause, alcohol use, and floor surface; for grip strength: difficulty paying for basics, dominant hand and dynamometer setting; for chair stand: difficulty paying for basics, foot covering; for decile score: number of comorbidities, difficulty paying for basics, and education;

b. Multivariable prospectivea risk (odds ratios) of balance limitations associated with 1) total Healthy Lifestyle Scoreb and 2) each healthy lifestyle behaviorb adjusted for other behaviors.

a. Healthy lifestyle behaviors measured at least 4 years prior to physical performance measures

b. Total healthy lifestyle score and each component score are treated as a continuous average over all available visits and range from 0-6 for the total healthy lifestyle score and 0 to 2 for component scores; results are presented as the odds ratio of any balance limitations for each increase in one point of the average score.

Note: Results are from two separate logistic regression models: one included the total healthy lifestyle score; the other included all three behavior component scores. Confounders included age, race, site, BMI, overall self-rated health, and arthritis, CES-D, foot covering, alcohol use and hormone use

Discussion

This study of the SWAN cohort found that, even with adjustment for multiple potential confounders, a composite measure of a healthy lifestyle, averaged over as many as 3 time points in a 10-year period in midlife, was strongly associated with faster walking speed, greater lower body strength, and better overall physical functioning, all assessed at least 4 years later. The only physical performance domains that were not impacted by the healthy lifestyle score in the fully adjusted models were balance and grip strength. In general, associations were similar in all of the race/ethnic groups and across the strata of BMI, with the exception of the 4 M walk which was associated with healthy lifestyle only in normal weight women. The findings were also consistent whether the healthy lifestyle score was expressed as a continuous or categorical variable or as a variable averaged over one or more visits or a time-specific variable measured 4, 9 or 13 years prior to the outcome.

However, when diet, smoking and physical activity were considered as separate behaviors, adjusted for each other, only physical activity remained significantly associated with the physical performance measures and accounted for most, or all, of the relation between the HLS and the performance measures. This may suggest that combining health behaviors into an overall composite score may actually be less informative than examing the influence of specific behaviors separately. Since the chair stand and the walking test are measures of lower body mobility and strength, and most physical activities improve those domains of physical fitness[4], it is not surprising that there is a close relation between physical activity and the specific tests of physical performance examined in this study. It is also consistent with a number of previous studies that have reported lower risk of disability and mobility impairment in elderly individuals who are physically active[27, 42]

On the other hand, these findings differ from some other studies that found that both smoking [25, 29] and unhealthy dietary intake[22, 25, 30, 32] were associated with increased risk of impaired lower body mobility. It is possible that the reason why neither abstention from smoking nor healthy diet were signficantly related to any of the physical performance domains in the SWAN cohort is that the prevalence of smoking was low (62.7% were never smokers) and the cut point for defining a healthy diet, based on the distribution, required meeting recommended intake of only 2 out of 8 dietary components.

One notable finding of the current analysis was that the positive influence of a healthy lifestyle on physical performance was attenuated in women who were overweight or obese only for the 4 meter walk and associations were generally independent of BMI. Many previous studies have demonstrated a direct association between BMI and functional limitations and onset of disability [8, 14, 25, 29, 32, 33], and BMI was an independent risk factor for poorer physical performance (except for grip strength) in this analysis as well (data not shown). However, the lack of evidence for either effect modification or confounding by BMI for the chair stand and the decile score suggests that BMI is not the primary mechanism accounting for the associations between healthy lifestyle behavior and integrated measures of lower body mobility and strength.

The absence of any independent association between the HLS and either balance or grip strength is also notable, and may be the result of the relatively young age of the SWAN cohort. The balance tasks assessed by the SPPB, which require each stance be held only for 10 seconds, may not be sufficiently challenging enough in the SWAN age range to detect variability in balance. Similarly, grip strength, which is indicative of muscle strength and muscle mass and has prognostic value in terms of mortality in the elderly, particularly the frail elderly[13], may be influenced more by overall body size in this younger population. Nonetheless, there was a significant association between physical activity and grip strength, suggesting that behavior that preserves muscle mass is important, even at this relatively young age.

This study does have some limitations that need to be considered. Most importantly, there was no baseline measure of physical performance, which made it impossible to either adjust for the starting level of objectively measured physical function or to examine change in physical function. However, the positive impact of the healthy lifestyle score on physical performance was still evident when only women who self-reported no functional limitation at all at baseline were considered (data not shown), which supports the appropriate temporal relation between healthy lifestyle and physical performance. Another limitation was the reliance on self-reported physical activity which is subject to misclassification bias[3].

The present study makes several unique contributions to the existing body of literature examining healthy lifestyle behavior and physical function and disability. First, it may be the only study to examine a composite healthy lifestyle score, averaged over as many as 10 years, in relation to objective measures of physical function, measured at least four years later. Second, it was conducted among a relatively young population that ranged in age from 42-52 years old at the start of the study and from 56 to 68 when physical performance was assessed; this fills a gap in knowledge about the impact of health behaviors on physical function in the period between late midlife and early older adulthood. Finally, the study was conducted among a racially, ethnically diverse cohort, representative of the population of midlife women in the United States.

This study has clear clinical and public health implications. Even at this relatively young age of the SWAN cohort, the average walking speed of those with an “unhealthy” lifestyle was 1.1 m/sec, which is the minimal walking speed set by the Federal government for safely crossing an intersection with a traffic signal [40]). As the individuals in this group age, it is reasonable to expect that their walking speed will slow even more, putting them at risk for injury, morbidity and mortality [16, 17]. Futhermore, given the aging of the population[9] and the considerable risk for functional impairment and disability in the elderly, identifying strategies in midlife for reducing the risk of future loss of independence is a high public health priority. Large population-based efforts to promote physical activity have been underway for quite some time and need to continue and expand, particularly in minority and less advantaged communities. The greater the resources expended on prevention of disability in midlife, the less will be the resources required by both the individual and society to deal with disability in later life.

Acknowledgments

The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DHHS, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH) (Grants U01NR004061, U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, U01AG012495). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH or the NIH.

The results of the study have been presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification or inappropriate data manipulation.

The results of the current study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Adams PF, Marano MA. Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 1994. Vital Health Stat 10. 1995;(193 Pt 1):1–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ainsworth BE, Sternfeld B, Bensfield E. Evaluation of the Kaiser Physical Activity Survey in Women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(7):1327–38. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200007000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ainsworth B, Levy S. Assessment of health-enhancing physical activity Methodological Issues. In: Oja P, Borms J, editors. Health Enhancing Physical Activity. Oxford, UK: Meyer & Meyer Sport; 2004. pp. 239–270. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(6):992–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Block G, Hartman AM, Dresser CM, Carroll MD, Gannon J, Gardner L. A data-based approach to diet questionnaire design and testing. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:453–469. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Block G, Thompson FE, Hartman AM, Larkin FA, Guire KE. Comparison of two dietary questionnaires validated against multiple dietary records collected during a 1-year period. J Am Diet Assoc. 1992;92(6):686–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Block G, Woods M, Potosky A, Clifford C. Validation of a self-administered diet history questionnaire using multiple diet records. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(12):1327–1335. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90099-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brach JS, VanSwearingen JM, Fitzgerald SJ, Storti KL, Kriska AM. The relationship among physical activity, obesity, and physical function in community-dwelling older women. Prev Med. 2004;39(1):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in aging--United States and worldwide. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(6):101–4. 106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakravarty EF, Hubert HB, Krishnan E, Bruce BB, Lingala VB, Fries JF. Lifestyle risk factors predict disability and death in healthy aging adults. Am J Med. 2012;125(2):190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dall TM, Gallo P, Koenig L, Gu Q, Ruiz D. Modeling the indirect economic implications of musculoskeletal disorders and treatment. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2013;11(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferris BG. Epidemiology Standardization Project (American Thoracic Society) Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118(6 Pt 2):1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman N, Glei DA, Rosero-Bixby L, Chiou ST, Weinstein M. Performance-based measures of physical function as mortality predictors: Incremental value beyond self-reports. Demogr Res. 2014;30(7):227–252. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2013.30.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gretebeck RJ, Ferraro KF, Black DR, Holland K, Gretebeck KA. Longitudinal change in physical activity and disability in adults. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36(3):385–394. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.3.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guenther PM, Casavale KO, Reedy J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hiza HA, Kuczynski KJ, et al. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2010. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(4):569–580. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, Leveille SG, Markides KS, Ostir GV, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(4):M221–M231. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haveman-Nies A, de Groot LC, Van Staveren WA. Relation of dietary quality, physical activity, and smoking habits to 10-year changes in health status in older Europeans in the SENECA study. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):318–323. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosmer DW, L S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houston DK, Ding J, Nicklas BJ, Harris TB, Lee JS, Nevitt MC, et al. The association between weight history and physical performance in the Health, Aging and Body Composition study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(11):1680–1687. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houston DK, Stevens J, Cai J, Haines PS. Dairy, fruit, and vegetable intakes and functional limitations and disability in a biracial cohort: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(2):515–522. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.81.2.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang MH, Schocken M, Block G, Sowers M, Gold E, Sternfeld B, et al. Variation in nutrient intakes by ethnicity: results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Menopause. 2002;9(5):309–319. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200209000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iezzoni LI, Kurtz SG, Rao SR. Trends in U.S. adult chronic disability rates over time. Disabil Health J. 2014;7(4):402–412. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koster A, Penninx BW, Newman AB, Visser M, van Gool CH, Harris TB, et al. Lifestyle factors and incident mobility limitation in obese and non-obese older adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(12):3122–3132. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138(11):923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marques EA, Baptista F, Santos DA, Silva AM, Mota J, Sardinha LB. Risk for losing physical independence in older adults: The role of sedentary time, light, and moderate to vigorous physical activity. Maturitas. 2014;79(1):91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michael YL, Smit E, Seguin R, Curb JD, Phillips LS, Manson JE. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and physical performance in postmenopausal women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20(11):1603–1608. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostbye T, Taylor DH, Jr, Krause KM, Van SL. The role of smoking and other modifiable lifestyle risk factors in maintaining and restoring lower body mobility in middle-aged and older Americans: results from the HRS and AHEAD. Health and Retirement Study. Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(4):691–699. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radavelli-Bagatini S, Zhu K, Lewis JR, Dhaliwal SS, Prince RL. Association of dairy intake with body composition and physical function in older community-dwelling women. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(12):1669–1674. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shahar DR, Houston DK, Hue TF, Lee JS, Sahyoun NR, Tylavsky FA, et al. Adherence to mediterranean diet and decline in walking speed over 8 years in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1881–1888. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharkey JR, Branch LG, Giuliani C, Zohoori M, Haines PS. Nutrient intake and BMI as predictors of severity of ADL disability over 1 year in homebound elders. J Nutr Health Aging. 2004;8(3):131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sowers MF, Crawford SL, Sternfeld B. A multicenter, multiethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition. In: Lobo RA, Kelsey J, Marcus R, editors. Menopause: Biology and Pathobiology. San Diego, Ca: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 175–88. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sternfeld B, Ainsworth BE, Quesenberry CP. Physical activity patterns in a diverse population of women. Prev Med. 1999;28(3):313–323. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevens J. Ethnic-specific revisions of body mass index cutoffs to define overweight and obesity in Asians are not warranted. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(11):1297–1299. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomey K, Sowers MR, Harlow S, Jannausch M, Zheng H, Bromberger J. Physical functioning among mid-life women: associations with trajectory of depressive symptoms. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(7):1259–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tseng LA, El Khoudary SR, Young EA, Farhat GN, Sowers M, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. The association of menopause status with physical function: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2012;19(11):1186–1192. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182565740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S.Department of Health and Human Services OoDPaHP. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration. Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration; 2009. [Accessed September 1, 2016]. Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways. http://mutcd.fhwa.dot.gov/pdfs/2009r1r2/pdf_index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Visser M, Pluijm SM, Stel VS, Bosscher RJ, Deeg DJ. Physical activity as a determinant of change in mobility performance: the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(11):1774–1781. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ware JE. SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams ED, Eastwood SV, Tillin T, Hughes AD, Chaturvedi N. The effects of weight and physical activity change over 20 years on later-life objective and self-reported disability. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(3):856–865. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ylitalo KR, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Fitzgerald N, Zheng H, Sternfeld B, El Khoudary SR, et al. Relationship of race-ethnicity, body mass index, and economic strain with longitudinal self-report of physical functioning: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23(7):401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]