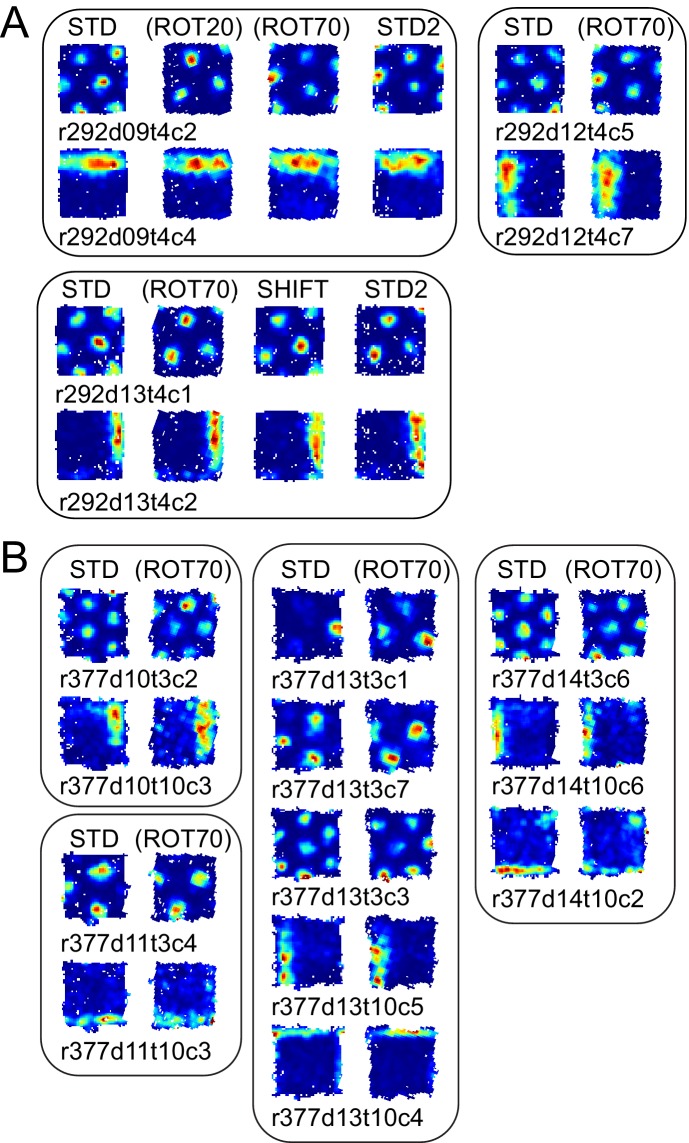

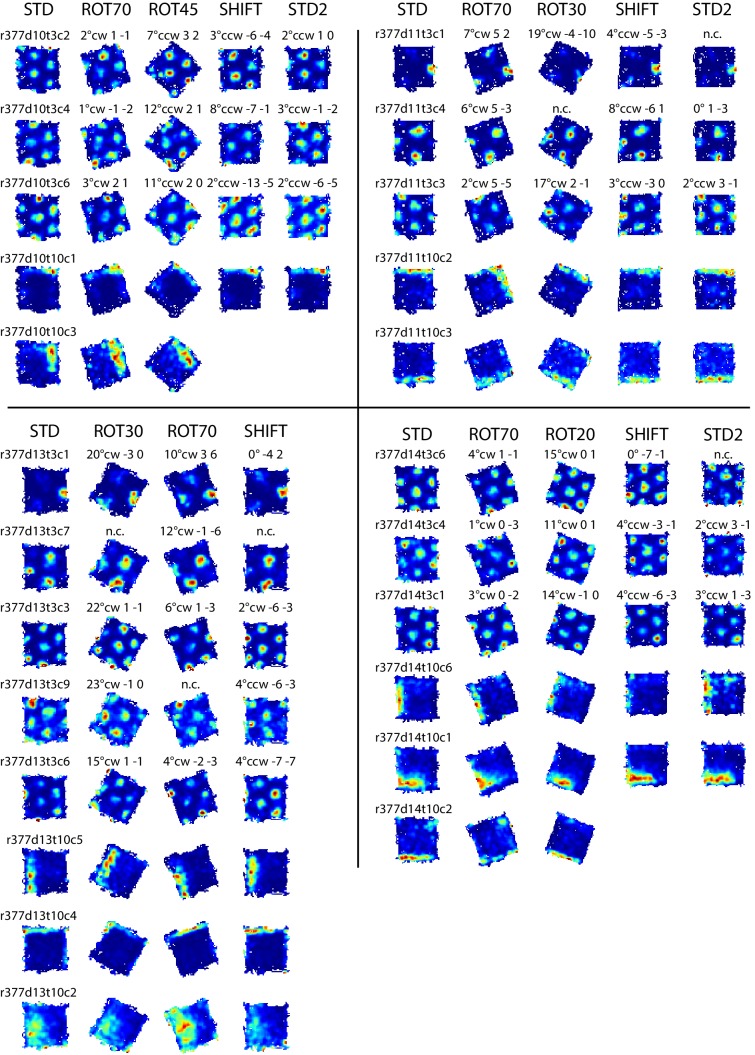

Figure 7. More examples of grid and boundary cells recorded simultaneously from rats 292 (A) and 377 (B).

Each simultaneously recorded set is in a separate bounding box. The rate maps for sessions labeled in parentheses were rotated to aid visual comparison of the changing firing patterns of grid cells vs. the repeating patterns of boundary cells. Rate maps for all sessions in which these cells were recorded are given in Figure 6, Figure 6—figure supplement 2 (rat 292) and Figure 7—figure supplement 1 (rat 377).