Abstract

NR1 knockdown (NR1KD) mice are genetically modified to express low levels of the NR1 subunit of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, and show deficits in affiliative social behaviour. In this study, we determined which brain regions were selectively activated in response to social stimulation and asked whether differences in neuronal activation could be observed in mice with reduced sociability. Furthermore, we aimed to determine whether brain activation patterns correlated with the amelioration of social deficits through pharmacological intervention. The cingulate cortex, lateral septal nuclei, hypothalamus, thalamus and amygdala showed an increase in c-Fos immunoreactivity that was selective for exposure to social stimuli. NR1KD mice displayed a reduction in social behaviour and a reduction in c-Fos immunoreactivity in the cingulate cortex and septal nuclei. Acute clozapine did not significantly alter sociability; however, diazepam treatment did increase sociability and neuronal activation in the lateral septal region. This study has identified the lateral septal region as a neural substrate of social behaviour and the GABA system as a potential therapeutic target for social dysfunction.

Keywords: Antipsychotic, benzodiazepine, GABA, glutamate, neural substrate, NMDA, social behaviour

Sociability is defined as the tendency to seek out social interactions (Caldwell 2012). In terms of the neural substrates that regulate sociability, there are striking similarities across the vertebrate species (Goodson 2005; Newman 1999). A number of studies have outlined the ‘social behaviour network’, which is comprised of the medial amygdala, bed nucleus of stria terminalis (BNST), lateral septum, medial preoptic area, the anterior hypothalamus, the ventromedial hypothalamus and the periaqueductal grey (Goodson 2005; Newman 1999). Each of these nodes of the ‘social behaviour network’ have all been implicated in the mediation of a number of social behaviours including aggression, sexual behaviour, various forms of communication, social recognition, affiliation, bonding, parental behaviour and responses to social stressors (Goodson 2005).

Because humans are highly social animals, deficits in social interaction are often debilitating, and as such are diagnostic features of autism and schizophrenia. Social withdrawal in schizophrenia is one of the symptoms that does not respond well to pharmacological treatments and this prevents patients from participating in normal daily activities (Yizhar 2012). To improve treatment for social withdrawal, it is important to delineate the areas of the brain that are responsible for different aspects of social interaction, and study how pharmacological interventions affect functioning of these areas.

In this study, we wanted to determine how the neural activity of the social brain is affected by impaired N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor signalling, which has been proposed to contribute to the social deficits observed in schizophrenia and autism (Gandal et al. 2012a). NMDA receptor (NMDAR) antagonists, such as phencyclidine (PCP), are known to induce social withdrawal in humans and animal models (Corbett et al. 1995); however, acute antagonism is not likely to fully model chronic diseases such as schizophrenia. Therefore, we used a genetic mouse model of NMDAR deficiency, the NR1 knockdown (NR1KD) mouse, to understand how the social brain is impacted.

NR1 knockdown mice (also termed Nr1neo−/−) have only 10–15% of wildtype levels of NMDARs because of a hypomorphic mutation in the gene that encodes the essential NR1 subunit of these receptors (Mohn et al. 1999). Studies from multiple laboratories have demonstrated robust alterations in social interaction in a number of behavioural paradigms, including resident-intruder assays and a modified three-chamber sociability paradigm (Duncan et al. 2004, 2009; Halene et al. 2009; Mohn et al. 1999; Ramsey et al. 2011). In this study, we compared the pattern of neural activation in NR1KD mice with that in wildtype mice in response to a non-threatening, novel, social stimulus. This study focused on the lateral septum and cingulate cortex, two brain regions that have been previously identified to regulate social interaction (Goodson 2005). In addition, we studied the ability of two drugs, clozapine and diazepam, to normalize social interactions and patterns of neuronal activation within these brain regions.

Materials and methods

Animal subjects

Adult (13–15 weeks) male mice (NR1KD or wildtype littermates) were used. NR1KD mice express low levels of the NR1 subunit of the NMDAR; the hypomorphic mutation is achieved by the targeted insertion of a neomycin cassette into intron 17 of the Grin1 sequence, reducing levels of full-length mRNA, as described (Mohn et al. 1999). Experimental mice (NR1KD and wildtype littermates) were generated from intercross breeding of congenic C57BL/6 J NR1KD heterozygotes with congenic 129X1Sv/J NR1KD heterozygotes, producing F1 progeny of a defined genetic background. Animal housing and experimentation were carried out in accordance with the Canadian Council in Animal Care (CCAC) guidelines for the care and use of animals and an approved animal protocol from the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy Animal Care Committee at the University of Toronto. Animals were housed on a 12-h light–dark cycle (0700 to 1900 h) and were given access to food (2018 Tekland Global 18% Protein Rodent Diet, Harlan Laboratories Canada Ltd., Toronto, ON, Canada) and water ad libitum.

Drug administration

Clozapine (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; Cat. No. C6305) was dissolved in saline acidified with glacial acetic acid (1%) to a final 0.1 mg/ml solution. Experimental animals were administered clozapine (1.0 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection 1 h prior to starting the social affiliative behaviour paradigm. Diazepam (Toronto Research Chemicals, Toronto, ON, Canada; Cat. No. D416855) was dissolved in 95% ethanol to make a 5 mg/ml solution, subsequently prepared to a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml in saline solution. Experimental animals were administered diazepam (2.0 mg/kg) via i.p. injection 30 min prior to starting the social affiliative behaviour paradigm.

Social affiliative behaviour paradigm

Male wildtype and NR1KD mice aged 13–15 weeks were assessed in a social affiliative behaviour paradigm to measure sociability. All behavioural tests were completed between 0800 and 1200 h. Sociability was measured via video recording using gender and age-matched mice (C3H/HeJ inbred mouse, novel to the test subject) as social stimuli. The experimental mouse (wildtype or NR1KD; drug-treated or vehicle) was allowed to explore the open arena (opaque white walls, 62 × 42 × 22 cm) for 10 min. The arena contained two inverted wire cups [as described by Crawley (2004)], one containing a stimulus mouse (‘social’ area) and the other empty (‘non-social’ area). This was a modified version of the three-chamber social approach paradigm, as described by Nadler et al. (2004), where there were no dividing walls (forming three chambers) in the arena. Instead, the arena is one ‘chamber’ where the test mouse freely explores the open area and wire cups (social and non-social) (Fig. 2a). Over the 10-min period, the test mouse was video-recorded and its movements were tracked using Biobserve Viewer (version 2) software. Sociability was measured as follows: (1) time spent in social zone, which is the time spent in the 3 cm zone around the cup containing the social stimulus mouse, (2) social investigation, which is the difference between time spent in social investigation (social zone) and time spent in non-social/novel object investigation (non-social zone) and (3) time spent in the social zone per visit, which is the time spent in the social zone divided by the number of visits.

c-Fos immunohistochemistry

Neuronal activation was quantified using induction of c-Fos expression as a biochemical marker as described (Bullitt 1990); protein product can be detected 20–90 min following neuronal excitation. 60 minutes (median of time range for the detection of protein product) following completion of the social affiliative behaviour paradigm described above, mice were anaesthetized with 250 mg/kg Avertin [2,2,2-tribromoethanol (Sigma Aldrich, Cat. No. T48402) dissolved in 2-methyl-2-butanol (Sigma Aldrich, Cat. No. 152463) (2.5% v/v)] administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) and transcardially perfused through the right ventricle with cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (w/v) using a peristaltic pump P-1 (GE Healthcare, Baie d’Urfe, QC, Canada). Brains were post-fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C for 3–4 h, followed by cryopreservation in 30% (w/v) sucrose solution for 3 days at 4°C, and then sectioned with a cryostat (40 μm coronal sections; 1.0–0.3 mm Bregma). Alternatively, 100 μm sagittal (0.12 and 1.92 mm lateral) sections were collected by vibratome for representative images of neuronal activation following exposure to social stimuli (Fig. 1). Sections were processed for c-Fos immunoreactivity as described (Ramsey et al. 2008). Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody anti-c-Fos (Ab-2) (4–17) (Calbiochem, Hessen, Germany; Cat. No. PC05; 1:5000).

c-Fos immunoreactive neurons within sagittal sections (representative images; Fig. 1) were imaged by confocal microscopy. c-Fos immmunoreactive neurons (coronal sections; Figs. 4,6,8) were quantified in a semi-automated manner using Nikon Elements software (NIS-Elements Basic Research, version 3.10) at a magnification of 20X by a blinded experimenter. Using automatic exposure, fluorescent intensity thresholds were set automatically and adjusted to fall within the linear range. Three basic operations were performed on the binary layer (clean: 6X, smooth: 6X and separate: 4X). Defining limits were set on size restriction (between 0.025 and 0.5 mm) and circularity (between 0.00 and 1.00). The two brain regions selected for quantification were cingulate cortex [0.13 mm2/field, 12 fields total (6/hemisphere), 1.6 mm2 total area] and lateral septal region [0.13 mm2/field, 4 fields total (2/hemisphere), 0.53 mm2 total area] (Fig. 2b).

Statistical analysis

Data for sociability were analysed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test comparing measures of sociability with respect to genotype (wild type or NR1KD; Fig. 3) or drug treatment (NR1KD vehicle compared with NR1KD drug; Figs. 5,7). Data for each brain region were analysed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test, comparing factors of genotype (Fig. 4) or drug treatment (Figs. 6, 8). For all comparisons, data are represented as the mean ± SEM and significance set at P < 0.05. Statistically calculated outliers (for both behaviour and c-Fos immunohistochemistry) were excluded from data using Grubbs’ test: Fig. 3c – one excluded from NR1KD; Fig. 5a – one excluded from NR1KD clozapine; Fig. 5b – one excluded from NR1KD vehicle; Fig. 5c – one excluded from NR1KD in both vehicle and clozapine; Fig. 7b – one excluded from NR1KD diazepam; Fig. 8a – one excluded from NR1KD diazepam lateral septal nuclei. Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 6.

Results

c-Fos immunoreactivity identifies brain regions that are selectively activated by interaction with a novel mouse

c-Fos immunoreactivity is routinely used as an indicator of neuronal activity, as nuclear c-Fos protein is produced 20–90 min following intense neuron activity (Bullitt 1990). In this study, wildtype mice were exposed to a novel mouse to measure c-Fos immunoreactivity and identify the brain regions that are activated following social stimulation. In this paradigm, the tested mouse was placed in an open arena with two inverted wire cups, one empty and one containing a novel male mouse, the social stimulus mouse. The genetic background of the social stimulus was C3H/HeJ, which has been used in other social interaction paradigms because it displays highly sociable behaviour (Moy et al. 2007). Test animals that spent at least 3 min engaged in social investigation were used for subsequent expression analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Identification of social regions in mouse brain.

Neuron activation patterns were determined by c-Fos immunoreactivity 1 h post-exposure to a social stimulus (social) or an empty arena (non-social). The brain regions that were more activated by social stimulus, than non-social stimulus, include the amygdala, cingulate cortex, hypothalamus, lateral septum and thalamus. Illustrations of sagittal sections at 0.12 and 1.92 mm from the midline demonstrate the location of brain structures that were analysed. Confocal micrographs at 10X magnification depict representative images of c-Fos immunoreactivity.

Because the test was performed in a novel arena with other non-social elements, such as the wire cups, a control group of wildtype males was tested in the same arena with two wire cups, but without the presence of the social stimulus mouse. This was done to control for neuron activation mediating locomotion, olfaction and vision that occurs with investigation of a novel environment.

By comparing the c-Fos labelling of the two groups of wildtype mice (exposed to social stimulus or non-social stimulus), several brain regions show selective activation in response to a social stimulus (Fig. 1). The brain regions that were more activated in the social exposure than the non-social exposure were the amygdala, cingulate cortex, hypothalamus, septal region and thalamus. We focused on the cingulate cortex and the septal region (Figs. 1,2b) for our subsequent studies in mutant mice.

Figure 2. Methods for the quantification of sociability in the social affiliative behaviour paradigm and the semi-automatic quantification of activated neurons.

(a) Quantification of sociability via video recording using gender and age-matched mice (C3H/HeJ inbred mouse, novel to the test subject) as social stimuli. The experimental mouse (wild type or NR1KD; drug-treated or vehicle) was allowed to explore the open arena (opaque white walls, 62 × 42 × 22 cm) for 10 min. The arena contained two inverted wire cups: one containing a stimulus mouse (‘social’ area) and the other empty (‘non-social’ area). (b) Semi-automatic quantification of activated (c-Fos immmunoreactive) neurons in the cingulate cortex and the lateral septal region. c-Fos immmunoreactive neurons were quantified in a semi-automated manner using Nikon Elements software at a magnification of 20X. The two brain regions selected for quantification were cingulate cortex [0.13 mm2/field, 12 fields total (6/hemisphere), 1.6 mm2 total area] and lateral septal region [0.13 mm2/field, 4 fields total (2/hemisphere), 0.53 mm2 total area]; 40 μm coronal sections, 1.0–0.3 mm Bregma.

NR1KD mice show a decrease in sociability and neuronal activation

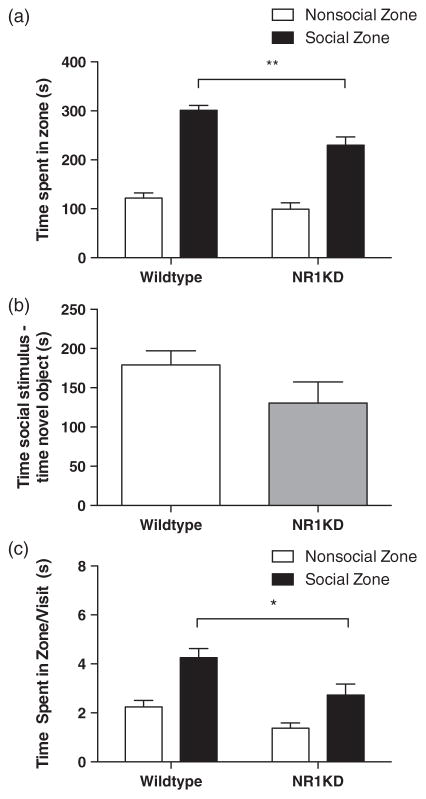

As the cingulate cortex and lateral septum were engaged during social interaction, we next asked whether there would be a change in the level of neuron activation within these regions in a mutant mouse with decreased sociability, the NR1KD mouse (Duncan et al. 2004; Halene et al. 2009; Mohn et al. 1999; Ramsey 2009; Ramsey et al. 2011). Wildtype and NR1KD male mice were tested in the social affiliative behaviour paradigm. NR1KD mice showed a marked decrease in social behaviour as quantified by a decrease in the amount of time spent in the social zone (Fig. 3a; WT 301.06 ± 10.24 seconds, NR1KD 229.73 ± 16.95 seconds, t18 = 3.752, P = 0.0015). NR1 knock-down mice also showed a decrease in time spent per visit to the social zone (Fig. 3c; WT 4.26 ± 0.38 seconds vs. NR1KD 2.73 ± 0.45 seconds, t17 = 2.609, P = 0.0183). NR1KD mice were not significantly different from wildtype mice when social investigation was measured as the difference between time spent in social minus time spent in non-social investigation, although there was a trend towards a decrease in social investigation (Fig. 3b; WT 179.10 ± 18.01 seconds vs. NR1KD 130.50 ± 26.88 seconds, t18 = 1.548 P = 0.1390). Levels of neuronal activation in the cingulate cortex and the lateral septal region correlated with the levels of sociability, as there was a marked decrease in c-Fos immunoreactivity in both regions of NR1KD brains (Fig. 4a; cingulate cortex – WT 689.10 ± 34.68/mm2, NR1KD 552.01 ± 15.52/mm2, t12 = 3.220, P = 0.0074; lateral septal region – WT 511.94 ± 42.34/mm2, NR1KD 384.80 ± 24.12/mm2, t12 = 2.375, P = 0.0351). This further supports a correlation between social behaviour (measured in terms of sociability) and neuronal activation patterns in two key neural substrates of social behaviour.

Figure 3. NR1KD mice show a decrease in sociability when compared with wildtype mice.

Behaviour in the social affiliative behaviour paradigm during a 10 min trial in WT and NR1KD male adult (13–15 weeks) mice (a, b, c). (a) Measure and comparison of total amount of time spent in social zone (black bars). (b) Measure and comparison of social investigation; the difference between time spent in social investigation (cup with social stimulus, social zone) and time spent in non-social/novel object investigation (empty cup, non-social zone) (investigation = time in social zone – time in non-social zone). (c) Measure and comparison of time spent in social zone per visit made (total time spent in zone/number of visits; black bars). All data shown as means ± SEM. Numbers for each group are as follows: (a) WT = 11, NR1KD = 9; (b) WT = 11, NR1KD = 9; (c) WT = 11, NR1KD = 8. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Figure 4. NR1KD mice show a decrease in neuronal activation in the cingulate cortex and lateral septal region following social exposure.

Activation (cell counts) of c-Fos-labelled neurons in WT and NR1KD male adult (13–15 weeks) mice (a). Representative images of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the cingulate cortex and the lateral septal region (b). (a) Quantification of neuronal activation following exposure to the social affiliative behaviour paradigm in the cingulate cortex and the septal region. (b) Representative images of neuronal activation and its semi-automated quantification (40 μm coronal sections, 1.0–0.3 mm Bregma). All data are represented as mean ± SEM. Numbers for each group are as follows: WT = 8, NR1KD =6. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

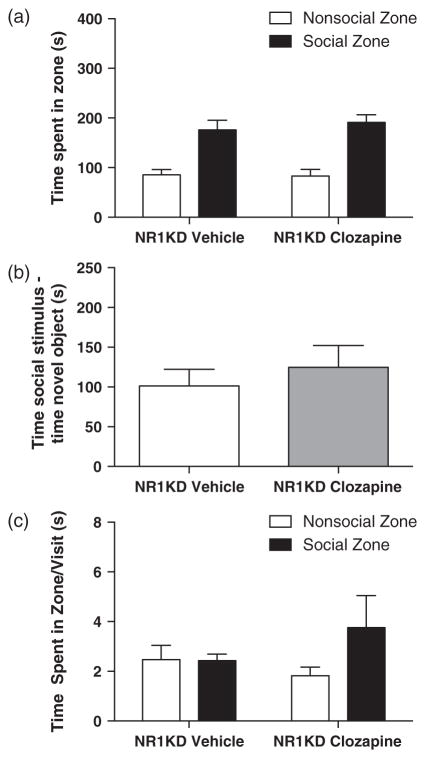

Acute clozapine does not increase social investigation or neuron activation in NR1KD mice

Our previous study indicated that the antipsychotic clozapine could improve some aspects of social interaction in NR1KD mice using a resident-intruder behavioural paradigm (Mohn et al. 1999). Therefore, we sought to normalize social investigation in NR1KD mice by acute clozapine treatment. Clozapine (1.0 mg/kg, i.p) or vehicle was administered to NR1KD mice 1 h prior to testing in the social affiliative behaviour paradigm. Acute clozapine treatment did not increase sociability in the three measures used in this study. There was no significant change in the total amount of time spent in the social zone (Fig. 5a; NR1KD vehicle 176.32 ± 19.12 seconds, NR1KD clozapine 191.18 ± 15.39 seconds, t20 = 0.6057, P = 0.5515.), or in social investigation (Fig. 5b; NR1KD vehicle 101.40 ± 20.77 seconds, NR1KD clozapine 124.70 ± 27.38 seconds, t20 = 0.6560, P = 0.5193) or in time spent per visit to the social zone (Fig. 5c; NR1KD vehicle 2.43 ± 0.26 seconds, NR1KD clozapine 3.759 ± 1.289 seconds, t19 = 0.9633, P = 0.3475). Furthermore, neuronal activation in the cingulate cortex and the lateral septal region remained unchanged (Fig. 6a; cingulate cortex – NR1KD vehicle 452.44 ± 66.89/mm2, NR1KD clozapine 449.11 ± 32.79/mm2, t12 = 0.04836 P = 0.9622; lateral septal region – NR1KD vehicle 355.90 ± 41.49/mm2, NR1KD clozapine 444.09 ± 57.98/mm2, t12 = 1.155, P = 0.2706).

Figure 5. Acute clozapine does not increase sociability in NR1KD mice.

Behaviour in the social affiliative behaviour paradigm during a 10 min trial in NR1KD male adult (13–15 weeks) mice treated with either acute clozapine (1.0 mg/kg) or vehicle (a, b, c). (a) Measure and comparison of total amount of time spent in social zone (black bars). (b) Measure and comparison of social investigation; the difference between time spent in social investigation (cup with social stimulus, social zone) and time spent in non-social/novel object investigation (empty cup, non-social zone) (investigation = time in social zone – time in non-social zone). (c) Measure and comparison of time spent in social zone per visit made (total time spent in zone/number of visits; black bars). All data shown as means ± SEM. Numbers for each group are as follows: (a) NR1KD vehicle = 11, NR1KD clozapine = 11; (b) NR1KD vehicle = 10, NR1KD clozapine = 12; (c) NR1KD vehicle = 10, NR1KD clozapine = 11. *P < 0.05.

Figure 6. Acute clozapine does not increase neuronal activation in the cingulate cortex or the lateral septal region following a social stimulus in NR1KD mice.

Activation (cell counts) of c-Fos-labelled neurons in NR1KD male adult (13–15 weeks) mice treated with either acute clozapine (1.0 mg/kg) or vehicle (a). Representative images of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the cingulate cortex and lateral septal region (b). (a) Quantification of neuronal activation following exposure to the social affiliative behaviour paradigm in the cingulate cortex and septal region. (b) Representative images of neuronal activation and its semiautomated quantification (40 μm coronal sections, 1.0–0.3 mm Bregma). All data are represented as mean ± SEM. Numbers for each group are as follows: NR1KD vehicle = 6, NR1KD clozapine = 8. *P < 0.05.

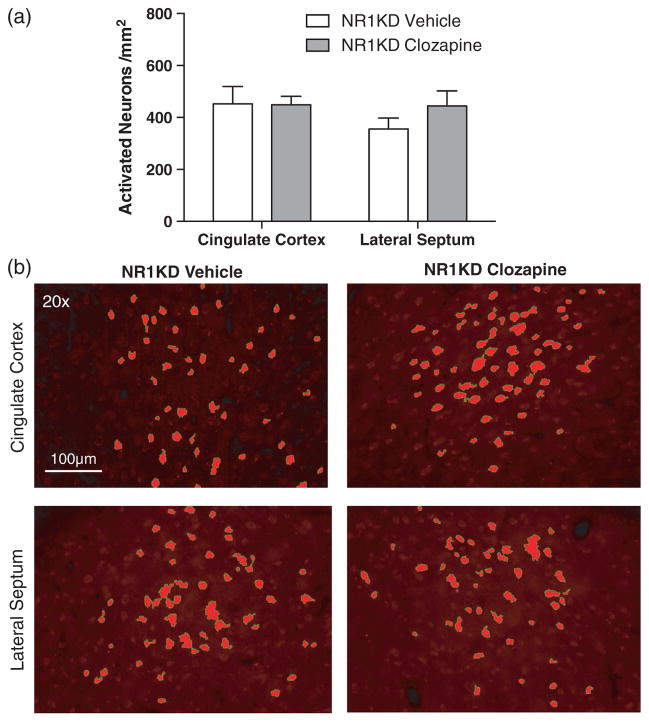

Acute diazepam increases sociability and neuronal activation in the lateral septal region of NR1KD mice

We next asked whether benzodiazepines, which reduce social anxiety in humans (Pollack 1999), could improve the social behaviour of NR1KD mice. NR1KD mice were treated acutely with the benzodiazepine diazepam (2.0 mg/kg, i.p) or vehicle 30 min prior to testing in the social affiliative behaviour paradigm. Acute diazepam treatment markedly increased sociability in NR1KD mice as measured by an increase in the amount of time spent in the social zone (Fig. 7a; NR1KD vehicle 152.67 ± 19.28 seconds, NR1KD diazepam 237.55 ± 25.98 seconds, t25 = 2.509, P = 0.0190), the time spent in social investigation (Fig. 7b; NR1KD vehicle 61.64 ± 18.37 seconds, NR1KD diazepam 191.80 ± 26.88 seconds, t24 = 3.864, P = 0.0007) and the time spent per visit to the social zone (Fig. 7c; NR1KD vehicle 2.59 ± 0.25 seconds, NR1KD diazepam 5.07 ± 0.95 seconds, t25 = 2.288, P = 0.0309). Of the two brain regions studied, neuronal activation in the lateral septal region showed the stronger correlation with improved behaviour. c-Fos immunoreactivity in the lateral septal region significantly increased with acute diazepam treatment prior to sociability testing (Fig. 8a; cingulate cortex –NR1KD vehicle 609.71 ± 24.76/mm2, NR1KD diazepam 616.12 ± 23.84/mm2, t11 = 0.1861, P = 0.8558; lateral septal region – NR1KD vehicle 510.45 ± 27.07/mm2, NR1KD diazepam 595.89 ± 16.66/mm2, t10 = 2.689, P = 0.0228).

Figure 7. Acute diazepam increases sociability in NR1KD mice.

Behaviour in the social affiliative behaviour paradigm during a 10 min trial in NR1KD male adult (13–15 weeks) mice treated with either acute diazepam (2.0 mg/kg) or vehicle (a, b, c). (a) Measure and comparison of total amount of time spent in social zone (black bars). (b) Measure and comparison of social investigation; the difference between time spent in social investigation (cup with social stimulus, social zone) and time spent in non-social/novel object investigation (empty cup, non-social zone) (investigation = time in social zone – time in non-social zone). (c) Measure and comparison of time spent in social zone per visit made (total time spent in zone/number of visits; black bars). All data are shown as means ± SEM. Numbers for each group are as follows: (a) NR1KD vehicle = 12, NR1KD diazepam = 15; (b) NR1KD vehicle = 12, NR1KD diazepam = 14; (c) NR1KD vehicle = 12, NR1KD diazepam = 15. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Figure 8. Acute diazepam increases neuronal activation in the lateral septal region following a social stimulus in NR1KD mice.

Activation (cell counts) of c-Fos-labelled neurons in NR1KD male adult (13–15 weeks) mice treated with either acute diazepam (2.0 mg/kg) or vehicle (a). Representative images of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the cingulate cortex and lateral septal region (b). (a) Quantification of neuronal activation following exposure to the social affiliative behaviour paradigm in the cingulate cortex and septal region. (b) Representative images of neuronal activation and its semi-automated quantification (40 μm coronal sections, 1.0–0.3 mm Bregma). All data are represented as mean ± SEM. Numbers for each group are as follows: NR1KD vehicle = 6, NR1KD diazepam = 7. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

The NR1KD mouse line is a developmental model of NMDAR hypofunction, in which a genetic disruption of NMDAR signalling leads to extensive behavioural abnormalities. Behavioural impairments include reduced social interactions and mating, locomotor hyperactivity, deficits in sensorimotor gating, self-injury and cognitive inflexibility (Duncan et al. 2004; Gandal et al. 2012a; Mohn et al. 1999). The profound reduction in social interactions within these mice is one of the most severe phenotypes observed (Gandal et al. 2012a). This decrease in sociability is not due to other confounding behaviours, such as hyperlocomotion, fear or increased anxiety; NR1KD mice exhibit a higher tendency to explore an open environment (elevated zero maze and open field test) (Halene et al. 2009). They also show little preference for a novel social stimulus over a novel unanimated object based on the social investigation score in this study. Furthermore, these mutant mice exhibit reduced huddling in home cages with cagemates during sleep, reduced social investigation of a resident intruder and reduced mating behaviour (Halene et al. 2009; Mohn et al. 1999). Therefore, the NR1KD mouse model is a robust model of reduced sociability, and a useful tool to identify neural substrates implicated in social behaviour.

This study was set out to identify key neural substrates of social affiliative behaviour, and to determine whether there is a relationship between activation of these substrates and changes in social behaviour. In this study, we identified several neural substrates (brain regions) in adult male wildtype mice that showed selective activation in response to a social stimulus, including the amygdala, cingulate cortex, hypothalamus, lateral septal region and the thalamus (Fig. 1). For this study, we focused on the cingulate cortex and the lateral septal region because of their known implications in social behaviour. NR1 knockdown adult male mice, a known model of decreased sociability (Duncan et al. 2004; Halene et al. 2009; Mohn et al. 1999; Ramsey 2009; Ramsey et al. 2011), showed a reduction in social affiliative behaviour (as measured in time spent in social zone, social investigation and time spent per visit) (Fig. 3) as well as a decrease in neuronal activation in both the cingulate cortex and the lateral septal region when compared with wildtype littermate controls (Fig. 4). Acute clozapine treatment did not ameliorate decreases in sociability in adult male NR1KD mice (Fig. 5), and caused no significant change in neuronal activation patterns in either the cingulate cortex or the lateral septal region when compared with vehicle controls (Fig. 6). Importantly, acute diazepam treatment did increase sociability in male NR1KD mice (Fig. 7), and also increased neuronal activation in the lateral septal region, but not in the cingulate cortex (Fig. 8).

To test sociability and quantify aspects of social behaviour, we used a modified version of the three-chamber social approach paradigm as previously described by Nadler et al. (2004). The social approach paradigm was chosen as a measure of sociability as there is no direct contact between mice (preventing confounding factors of aggression and fighting). Furthermore, this paradigm allows for automated scoring of sociability, ruling out subjectivity and bias from the experimenter (Hanks et al. 2013). The modified version of the three-chamber social approach paradigm abolishes the ‘chamber’ aspect (no walls divide the arena) and instead employs an open arena that contains two inverted wire cups, one representing the ‘social’ zone and the other the ‘non-social’ zone (Fig. 2a). This modified version of the social approach paradigm tracks ‘cylinder’ scores (times spent in a small area around the cylinder), rather than ‘chamber’ scores (time spent in respective chamber), to quantify sociability. These scores show a higher correlation with time spent in social interaction as well as a higher reliability and validity when compared with chamber scores (Fairless et al. 2011). Moreover, chamber scores can be subject to confounds such as grooming in the ‘social’ chamber, without any actual social investigation of the stimulus mouse (Hanks et al. 2013).

The observed reduction in social behaviour in NR1KD mice, and reduction in neuronal activation in the identified neural substrates, was not ameliorated with acute clozapine. The failure of clozapine to improve social approach supports some previous studies in NR1KD mice with atypical antipsychotics, and is also similar to clinical findings in patients treated with clozapine (Hanks et al. 2013). Although clozapine was effective to reduce escape behaviours of NR1KD mice in the resident-intruder paradigm, it did not improve approach-oriented behaviours in that study (Mohn et al. 1999). Despite the fact that clozapine has been shown to be somewhat more effective than other antipsychotics in improving negative symptoms and cognitive deficits of schizophrenia (Pereira et al. 2011), previous rodent studies have reported variable results in the ability of clozapine to ameliorate social deficits (Labrie et al. 2008).

Unlike clozapine, acute diazepam increased sociability (time spent in social zone, social investigation and time spent per visit) (Fig. 7). Diazepam also increased neuronal activation in the lateral septal region (Fig. 8). Diazepam is a classic benzodiazepine, acting as a positive allosteric modulator at gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABAA) receptors. Interestingly, several recent studies have highlighted the potential for GABA modulation (both GABAA and GABAB receptors) as a treatment for symptoms of syndromic autism, specifically cognitive deficits and social withdrawal (Gandal et al. 2012b; Han et al. 2014; Sandhu et al. 2014). In fact, a recent study has shown that baclofen (GABAB receptor agonist) improves social behaviour in NR1KD mice in a dose-dependent fashion (Gandal et al. 2012b).

There is a long history of benzodiazepine use in patient populations with schizophrenia, either as a monotherapy or, more commonly, as an adjunctive therapy to antipsychotics (Baandrup et al. 2011; Ciudad et al. 2006; Dold et al. 2012). It is evident that GABA modulation has some beneficial effects in ameliorating symptoms in this population; however, the underlying mechanism, whether as a monotherapy or in an adjunctive capacity, is not well known. In states of NMDAR hypofunction, low-dose GABA agonists may improve behaviours by increasing inhibitory transmission and correcting the imbalance between excitation and inhibition, as is observed in NR1KD mice. This study provides additional support for the suggestion that non-sedating, non-anxiolytic doses of GABA-positive modulators could be effective for schizophrenia and autism symptoms (Gandal et al. 2012b; Levitt et al. 2004; Lewis et al. 2005; Yizhar et al. 2011).

Diazepam also increased the activation of neurons in the lateral septum, a key component of the limbic system. The septum is involved in a number of functions, including learning and memory, emotions, fear and reward-seeking. More specifically, the lateral septal nucleus has strong projections to midbrain and hypothalamic regions, implicating strong associations in the modulation of social behaviour (Ophir et al. 2009; Veenema & Neumann 2008). Studies have shown that vasopressin-specific activation of the lateral septal region is critical for normal social recognition (Bielsky et al. 2005). GABAergic projections from the lateral septal to the anterior hypothalamus are important for the regulation of anxiety-like behaviours, undoubtedly contributing to overall social behaviour (Anthony et al. 2014). Therefore, by enhancing GABAergic signalling through diazepam treatment, it is reasonable to believe that a direct effect on the activation of neurons in the lateral septal region, as observed through neuronal activation patterns in this study (Fig. 8), reverses the decrease in sociability seen in the NR1KD mouse.

Although we have identified the lateral septal region as a neural substrate of social behaviour, and the GABA system as a potential therapeutic target for social dysfunction, there remain a number of other neural substrates that need to be investigated to gain a complete understanding of the circuitry and brain regions involved in social behaviour. Despite having solely investigated male–male non-aggressive social behaviour in this study, it is imperative to further examine the differing nuances of other social behaviours: sexual, maternal, aggressive behaviours, etc. Therefore, it will be beneficial to continue this study, investigating other neural substrates, as well as other social contexts, to gain a more rounded interpretation of possible targets in the treatment and amelioration of dysfunction in social behaviour.

References

- Anthony TE, Dee N, Bernard A, Lerchner W, Heintz N, Anderson DJ. Control of Stress-induced persistent anxiety by an extra-amygdala septohypothalamic circuit. Cell. 2014;156:522–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baandrup L, Fagerlund B, Jennum P, Lublin H, Hansen JL, Winkel P, Gluud C, Oranje B, Glenthoj BY. Prolonged-release melatonin versus placebo for benzodiazepine discontinuation in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial – the SMART trial protocol. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:160. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielsky IF, Hu SB, Ren X, Terwilliger EF, Young LJ. The V1a vasopressin receptor is necessary and sufficient for normal social recognition: a gene replacement study. Neuron. 2005;47:503–513. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullitt E. Expression of C-fos-like protein as a marker for neuronal activity following noxious stimulation in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;296:517–530. doi: 10.1002/cne.902960402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell HK. Neurobiology of sociability. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;739:187–205. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-1704-0_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciudad A, Olivares JM, Bousoño M, Gómez JC, Álvarez E. Improvement in social functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia with prominent negative symptoms treated with olanzapine or risperidone in a 1 year randomized, open-label trial. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30:1515–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett R, Camacho F, Woods AT, Kerman LL, Fishkin RJ, Brooks K, Dunn RW. Antipsychotic agents antagonize non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist-induced behaviors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;120:67–74. doi: 10.1007/BF02246146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN. Designing mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autistic-like behaviors. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:248–258. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dold M, Li C, Tardy M, Khorsand V, Gillies D, Leucht S. Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD006391. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006391.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GE, Moy SS, Perez A, Eddy DM, Zinzow WM, Lieberman JA, Snouwaert JN, Koller BH. Deficits in sensorimotor gating and tests of social behavior in a genetic model of reduced NMDA receptor function. Behav Brain Res. 2004;153:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan G, Inada K, Farrington J, Koller B, Moy S. Neural activation deficits in a mouse genetic model of NMDA receptor hypofunction in tests of social aggression and swim stress. Brain Res. 2009;1265:186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairless AH, Shah RY, Guthrie AJ, Li H, Brodkin ES. Deconstructing sociability, an autism-relevant phenotype, in mouse models. Anat Rec. 2011;294:1713–1725. doi: 10.1002/ar.21318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandal MJ, Anderson RL, Billingslea EN, Carlson GC, Roberts TPL, Siegel SJ. Mice with reduced NMDA receptor expression: more consistent with autism than schizophrenia? Genes Brain Behav. 2012a;11:740–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00816.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandal MJ, Sisti J, Klook K, Ortinski PI, Leitman V, Liang Y, Thieu T, Anderson R, Pierce RC, Jonak G, Gur RE, Carlson G, Siegel SJ. GABAB-mediated rescue of altered excitatory–inhibitory balance, gamma synchrony and behavioral deficits following constitutive NMDAR hypofunction. Transl Psychiatry. 2012b;2:e142–e149. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL. The vertebrate social behavior network: evolutionary themes and variations. Horm Behav. 2005;48:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halene TB, Ehrlichman RS, Liang Y, Christian EP, Jonak GJ, Gur TL, Blendy JA, Dow HC, Brodkin ES, Schneider F, Gur RC, Siegel SJ. Assessment of NMDA receptor NR1 subunit hypofunction in mice as a model for schizophrenia. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:661–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Tai C, Jones CJ, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Enhancement of inhibitory neurotransmission by GABAA receptors having α2,3-subunits ameliorates behavioral deficits in a mouse model of autism. Neuron. 2014;81:1282–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks AN, Dlugolenski K, Hughes ZA, Seymour PA, Majchrzak MJ. Pharmacological disruption of mouse social approach behavior: relevance to negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res. 2013;252:405–414. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie V, Lipina T, Roder JC. Mice with reduced NMDA receptor glycine affinity model some of the negative and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;200:217–230. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt P, Eagleson KL, Powell EM. Regulation of neocortical interneuron development and the implications for neurodevelopmental disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW. Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:312–324. doi: 10.1038/nrn1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohn A, Gainetdinov R, Caron M, Koller B. Mice with reduced NMDA receptor expression display behaviors related to schizophrenia. Cell. 1999;98:427–436. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81972-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Young NB, Perez A, Holloway LP, Barbaro RP, Barbaro JR, Wilson LM, Threadgill DW, Lauder JM, Magnuson TR, Jacqueline N, Crawley JN. Mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autism: phenotypes of 10 inbred strains. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176:4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler JJ, Moy SS, Dold G, Trang D, Simmons N, Perez A, Young NB, Barbaro RP, Piven J, Magnuson TR, Crawley JN. Automated apparatus for quantitation of social approach behaviors in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:303–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman SW. The medial extended amygdala in male reproductive behavior. A node in the mammalian social behavior network. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:242–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ophir AG, Zheng DJ, Eans S, Phelps SM. Social investigation in a memory task relates to natural variation in septal expression of oxytocin receptor and vasopressin receptor 1a in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:979–991. doi: 10.1037/a0016663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira A, Sugiharto-Winarno A, Zhang B, Malcolm P, Fink G, Sundram S. Clozapine induction of ERK1/2 cell signalling via the EGF receptor in mouse prefrontal cortex and striatum is distinct from other antipsychotic drugs. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;15:1149–1160. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack MH. Social anxiety disorder: designing a pharmacologic treatment strategy. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 9):20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey AJ. NR1 knockdown mice as a representative model of the glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia. Prog Brain Res. 2009;179:51–58. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17906-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey AJ, Laakso A, Cyr M, Sotnikova TD, Salahpour A, Medvedev IO, Dykstra LA, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Genetic NMDA receptor deficiency disrupts acute and chronic effects of cocaine but not amphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2701–2714. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey AJ, Milenkovic M, Oliveira AF, Escobedo-Lozoya Y, Seshadri S, Salahpour A, Sawa A, Yasuda R, Caron MG. Impaired NMDA receptor transmission alters striatal synapses and DISC1 protein in an age-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5795–5800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012621108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu KV, Lang D, Müller B, Nullmeier S, Yanagawa Y, Schwegler H, Stork O. Glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 haplodeficiency impairs social behavior in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2014;13:439–450. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenema AH, Neumann ID. Central vasopressin and oxytocin release: regulation of complex social behaviours. Prog Brain Res. 2008;170:261–276. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yizhar O. Optogenetic insights into social behavior function. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:1075–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Prigge M, Schneider F, Davidson TJ, O’Shea DJ, Sohal VS, Goshen I, Finkelstein J, Paz JT, Stehfest K, Fudim R, Ramakrishnan C, Huguenard JR, Hegemann P, Karl Deisseroth K. Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature. 2011;477:171–178. doi: 10.1038/nature10360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]