Abstract

Objective

Persons with chronic mental disorders are disproportionately burdened with physical health conditions. We determined whether Life Goals Collaborative Care compared to usual care improves physical health in patients with mental disorders within 12 months.

Method

This single-blind randomized controlled effectiveness study of a collaborative care model was conducted at a mid-western Veterans Affairs urban outpatient mental health clinic. Patients (N=293 out of 474 eligible approached) with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder and at least one cardiovascular disease risk factor were consented and randomized (02/24/10 to 04/29/15) to Life Goals (N=146) or usual care (N=147). A total of 287 completed baseline assessments and 245 completed 12-month follow-up assessments. Life Goals included five weekly sessions that provided semi-structured guidance on managing physical and mental health symptoms through healthy behavior changes, augmented by ongoing care coordination. The primary outcome was change in physical health-related quality of life score (VR-12 physical health component score). Secondary outcomes included control of cardiovascular risk factors from baseline to 12 months (blood pressure, lipids, weight), mental health-related quality of life, and mental health symptoms.

Results

Among patients completing baseline and 12-month outcomes assessments (N=245), the mean age was 55.3 (SD=10.8; range 28-75 years) and 15.4% were female. Intent-to-treat analysis revealed that compared to those in usual care, patients randomized to Life Goals had slightly increased VR-12 physical health scores (coefficient=3.21;p=0.01).

Conclusion

Patients with chronic mental disorders and cardiovascular disease risk who received Life Goals had improved physical health-related quality of life.

Keywords: care management, self-management, mood disorders, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Chronic mental disorders including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder1 are associated with worse physical health2,3 and premature mortality.2,4,5 A key driver is cardiovascular disease (CVD),2,6,7 and common physical health conditions, such as hypertension and obesity, disproportionately burden these patients with mental disorders6 and are also leading risk factors for CVD.

Poor self-management and unhealthy behaviors contribute up to 60% increased CVD-related mortality risk in this group.7 Lack of coordinated physical and mental health care, as well as limited dissemination of self-management strategies to support patients with mental health symptoms, can also further exacerbate morbidity and mortality risk.8-11

Treatment models for persons with chronic mental disorders need to address barriers to self-management and care coordination. Collaborative Care Models (CCMs),12 which provide proactive care for patients through self-management and care coordination have been shown to improve health outcomes, primarily for patients with depression.13,14 Life Goals Collaborative Care (LG-CC), a CCM-based intervention was shown to improve physical health-related quality of life, and reduce CVD risk factors in patients with bipolar disorder.15-18 However, to date LG-CC has not been tested in a broader psychiatric patient population, beyond single diagnoses.7

The goal of this single-blind randomized controlled trial was to determine whether LG-CC compared to usual care (UC) improved physical and mental health outcomes in 12 months among patients with chronic mental disorders who are at risk for CVD. Our primary hypothesis is that patients randomized to receive LG-CC compared to those randomized to receive usual care will have improved physical health-related quality of life (Veterans RAND 12-item Short Form Health Survey; VR-1219,20) scores from baseline to 12 months later. Commonly used in several clinical trials,21,22 improved health-related quality of life scores have been linked to improvements in CVD symptom-specific measures,23 and lower physical health-related quality of life scores was associated with a 2-3-fold increased risk in CVD-related mortality.24

Our secondary and exploratory hypotheses are compared to those enrolled in UC, patients in the LG-CC group will have improved mental health-related quality of life scores, , increased physical activity in 12 months, decreased psychiatric symptoms, and changes in intermediate and long-term CVD risk factors (Framingham Score25).

METHOD

This randomized controlled effectiveness intervention trial was conducted between 2/24/2010-02/15/2014 (with the last assessment completed 4/29/15) among adult patients diagnosed with chronic mental disorders with at least one CVD risk factor who received care in a large urban VA outpatient mental health clinic.26 This study received approval from the VA Ann Arbor Institutional Review Board. All patients provided informed consent, and the trial has been registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01487668 and NCT01244854).

Setting, Recruitment, and Participants

A clinical assessor, who was blinded to treatment allocation, screened for eligibility using electronic medical records per the following inclusion criteria:

Age 18 years or older with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder (single or recurrent) among patients receiving care in the mental health clinic. Mental disorder diagnosis was based on the presence of at least one inpatient or outpatient ICD-9-CM27 diagnosis of within the past year from the study recruitment start date (February 15, 2010). These diagnoses were chosen because they were considered the most chronic and debilitating mental health diagnoses that are primarily seen in VA mental health specialty.28 Previous research suggests that a single ICD-9 encounter code is sufficient for case ascertainment in studies in mental health clinics29. We used the following previously established diagnosis hierarchy to categorize patients: 1) schizophrenia, 2) bipolar disorder (but no presence of schizophrenia diagnosis), and 3) major depressive disorder diagnosis (without presence of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder diagnosis).30

- At least one of the following CVD risk factors recorded in the medical record:

- Body mass index (BMI) >28 or waist circumference >35 (women)/>40 (men) inches

- Diagnosis of or treatment for hypertension (diagnosis or blood pressure of >140/90 on 2 occasions or prescription for an antihypertensive medication),31 dyslipidemia (diagnosis or LDL>160 or prescription for a lipid-lowering medication), or diabetes mellitus (diagnosis or HbA1C >7% or current prescription for oral hypoglycemic therapy)

All potentially eligible participants based on medical record review were approached by the clinical assessor, who then confirmed eligibility and excluded potential participants based on the following criteria: 1) Unresolved substance intoxication or withdrawal (e.g., incoherent, slurred speech), 2) unwilling or unable to provide informed consent or comply with study requirements at the time of enrollment, or 3) expressing active suicidal ideation at time of enrollment (these patients were immediately referred to their mental health provider).

Those eligible and who consented to participate completed a baseline survey and underwent a clinical assessment that included systolic/diastolic blood pressure (two readings) and weight/height/waist circumference.

Treatment Assignment and Intervention

After confirmation of eligibility, documentation of informed consent, and completion of a baseline questionnaire and brief clinical assessment, participants were randomized to LG-CC or UC by a separate data analyst. Randomization was stratified by gender, age, race, and diabetes diagnosis (given that patients with diabetes may already be receiving health education and nutrition counseling through the VA).

LG-CC Intervention

Participants randomized to receive LG-CC were contacted by a study interventionist to schedule the first group self-management session. The interventionist (masters-level in health education) was trained over a 2-day period in LG-CC by study investigators using a previously established protocol.28,32-34 LG-CC, described in detail elsewhere,26 consisted of five group sessions lasting 90 minutes each session (with on average 10 participants per group), and subsequent care management contacts lasting on average 20 minutes each contact that were delivered by the interventionist for up to 6 months after the group sessions ended (Table 1). LG-CC is based on the Collaborative Care Model but customized to include use of symptom coping strategies that targeted CVD risk factors among persons with chronic mental disorders.35-39 LG-CC group sessions focused on helping patients manage mental health symptoms by promoting healthy behaviors that also addressed physical health issues, notably CVD risk, especially healthy eating and physical activity.

Table 1.

Life Goals Collaborative Care (LG-CC) Intervention and Usual Care Components

| Component | LG-CC Group | Usual Care Group |

|---|---|---|

|

Self-management

(Months 1-2) |

Five weekly self-management sessions by

health specialist Five group sessions (90 minutes, approx. 8-10 individuals per group cohort) covering:

|

|

|

Care Coordination

(Months 1-12) |

Care management:

|

|

|

Mental health clinic

resources (Months 1- 12) |

|

|

Monthly care management calls included monitoring of progress on achieving healthy behavior goals and additional guidance on symptom coping strategies. The interventionist also shared with providers the patients’ care plans, health goals, and guidelines for cardio-metabolic risk management for key psychotropic medications where appropriate.40 Taking provider contact time into consideration (5 minutes per encounter), the overall time the interventionist spent delivering LG-CC was 952 hours average 6.5 hours per participant).

Fidelity to the LG-CC intervention was tracked using in-person monitoring of group sessions to ensure core topic areas of the self-management program were completed. Session attendance and contact completion were also tracked for each participant. Using a previous definition which was associated with improved outcomes from LG-CC,41 adequate attendance was defined as participating in 4 out of 5 self-management sessions and completing at least four care management contacts.42

Usual Care

Patients who were randomized to usual care received routine VA care (Table 1), but were not provided LG-CC self-management sessions or ongoing contacts by the interventionist. UC included routine medication management provided by psychiatrists, as well as psychotherapy for specific diagnoses (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy) provided by mental health clinicians, but were not focused on CVD risk factors.

Data Collection and Measures

All study participants completed a survey and clinical exam that were administered at baseline, six, and twelve months by the clinical assessor. Survey questions covered the primary (physical health-related quality of life), secondary (mental health-related quality of life, measures of cardiovascular risk), and exploratory outcomes (symptoms, and other health behaviors), as well as covariates. The clinical exam was completed in-person in a private room in the mental health clinic and included CVD risk indicators including blood pressure (average of two readings of systolic and diastolic blood pressure ascertained when the patient was sitting down), and height/weight to calculate body mass index (BMI). Additional CVD risk factors including lipids were ordered as fasting labs through the VA medical record and the results were extracted by the outcomes assessor nearest to the baseline, 6, and 12 month survey dates.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome was changes in physical health-related quality of life between baseline and 12 months later. Physical health-related quality of life was found to be directly affected by LG-CC based on prior studies.15,17,18,24 The Veterans Short-Form (VR)-12,19,20 a widely used and validated instrument, was the source of data on physical health-related quality of life. The VR-12 generated a physical health (PCS) and mental health (MCS) composite score, in which each component score ranged from 0-100, whereas a higher score represented better health-related quality of life.

Secondary outcomes included mental health-related quality of life based on the aforementioned MCS score, as well as measures of CVD risk including systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), and physical activity.17,18 Physical activity was ascertained from the patient survey using the Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF),43 a self-reported four-item measure of habitual physical activity over the past 7 days. IPAQ-SF ascertains information on time spent walking in moderate intensity, in vigorous-intensity, and sitting, on weekdays and weekend days.

Other exploratory outcomes included psychiatric symptoms, 10-year CVD risk based on the Framingham score,25 and waist circumference. Psychiatric symptoms are ascertained from the patient survey and include mood, psychosis, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms.44 Mood symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)45 and the Internal State Scale (ISS).46,47 Psychotic symptoms were ascertained 5-item Behavior Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS©).48 Anxiety symptoms were measured using the GAD-7, a 7-item self-report tool designed to screen for the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). The GAD-7 measure is recognized for its reliability and validity for assessing anxiety.49 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms were assessed based on the PTSD CheckList – Civilian Version (PCL-C) 17-item measure which includes key symptoms of PTSD.50,51

The Framingham Risk Score25 estimated 10-year risk of acquiring CVD based on a weighted score derived from blood pressure data, diabetes diagnosis (VA electronic medical record diagnoses at baseline), patient age, sex, and current smoking status (from the baseline survey), and fasting low-density lipoprotein levels in mg/dL ascertained from the VA electronic medical record review52-55 based on lab results recorded nearest to the patient’s assessment dates at baseline, 6 and 12 months. Finally, socio-demographics and other health behaviors were ascertained from the participant survey.56,57

Sample Size and Power

The sample size for the study (N=240) enabled a minimum power of .80 to detect a small to moderate effect (Cohen’s D>.30),17,18 at a significance level of .05 (using a two-tailed statistical test) on our primary outcome.58

Analysis

Repeated measures analyses were used to assess the intervention effects on changes in outcomes, adjusting for LG-CC, time (6, 12 month using dummy indicators), the interaction between LG-CC and time, as well as baseline variables that were significantly different between in the intervention and control groups. All the analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (U.S. Cary, NC) and included the 245 individuals with complete baseline and 12-month data. The coefficients reported represent main effects of the difference in LG-CC scores compared to differences in the usual care scores over the baseline and 12-month period. Primary and secondary outcomes were changes over the baseline and 12-month period between LG-CC and usual care groups.

RESULTS

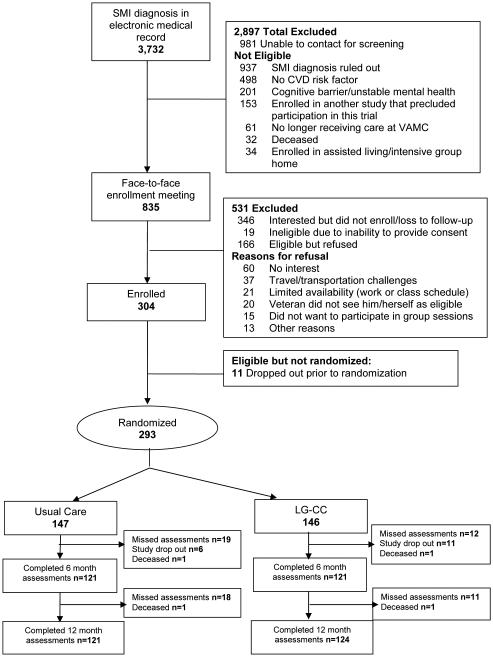

A total of 3,732 eligible patients were screened for study participation, of which 2,897 were not found to be eligible (Figure 1). Of the 835 approached, 474 were found to be eligible, and of those, 304 agreed to participate and were enrolled. Out of the 304, a total of 11 dropped out prior to randomization, resulting in a final baseline sample size of 293, and 245 of the 293 completed baseline and 12 month assessments. The mean age was 55.3 (SD=10.8; range 28-75 years), 44 (15.4%) were women, 50 (18.1%) were African-American, reflecting similar demographics in this VA mental health clinic (mean age = 55, 6% female, 11% African-American). The majority 165(57.5%) were diagnosed with depression (Table 2).

Figure 1.

CONSORT: Participant Recruitment and Enrollment Flow Diagram

Table 2.

Participant Demographic and Clinical Characteristicsa

| Total (N =287) |

LG-CC (N=141) |

Usual care (N =146) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± sd or median (IQR) |

% | mean ± sd or median (IQR) |

% | mean ± sd or median (IQR) |

% | t | p-value | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age;Range:25-78 yrs | 55.3 ± 10.8 | 55.3 ± 10.7 |

55.4 ± 11.0 | .08 | .93 | |||

| Age breakdown | ||||||||

| <50 years | 25.7 | 24.3 | 27.1 | .86 | ||||

| 50-59 years | 31.3 | 32.1 | 30.6 | |||||

| ≥ 60 years | 42.9 | 43.6 | 42.4 | |||||

| Female | 15.4 | 15.6 | 15.3 | .93 | ||||

| Black (vs. non-Black) | 18.1 | 22.1 | 14.2 | .08 | ||||

| Some college education | 72.9 | 73.8 | 72.2 | .77 | ||||

| Lives alone | 32.2 | 29.6 | 34.8 | .35 | ||||

| Clinical Factors | ||||||||

| Current Diagnosisb | ||||||||

| Schizophrenia | 7.3 | 5.7 | 8.9 | .67 | ||||

| Bipolar disorder | 24.0 | 23.4 | 24.7 | |||||

| Major depressive disorder | 57.5 | 60.3 | 54.8 | |||||

| Other SMI diagnosis | 11.2 | 10.6 | 11.6 | |||||

| Current Substance Use | ||||||||

| Current Smoker | 26.1 | 23.5 | 28.6 | .33 | ||||

| Alcohol misuse | ||||||||

| AUDIT-C Scorec | 0 (0,3) | 0 (0,3) | 0 (0,3) | .88 | ||||

| % Hazardous Drinking | 12.3 | 11.8 | 12.9 | .78 | ||||

| Current CVD Diagnosisd | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 63.8 | 65.3 | 62.3 | .60 | ||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 62.0 | 62.4 | 61.6 | .89 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 31.4 | 34.0 | 28.8 | .33 | ||||

| Medicationse | ||||||||

| Antipsychotics | 38.0 | 33.1 | 42.8 | .09 | ||||

| Antidepressants | 83.5 | 85.6 | 81.4 | .33 | ||||

| Mood Stabilizers | 52.1 | 49.6 | 54.5 | .41 | ||||

| Statins | 51.2 | 52.5 | 50.0 | .67 |

Statistical method: Chi-squared test for categorical variables (% reported); Two independent samples t-test for numeric variables (mean ± sd reported); Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for the variables with a highly skewed distribution (median (IQR) reported).

Mental disorder diagnosis based on medical record review and delineated based on the following diagnosis hierarchy: 1) schizophrenia, 2) bipolar disorder but no presence of schizophrenia diagnosis, and 3) major depressive disorder diagnosis (without diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder).

Current hazardous drinking is based on the score of one item of AUDIT-C defined as having 6 or more drinks on one occasion in the past month (yes/no). AUDIT-C scores are defined on 0-12 scale and based on 3 items with higher scores indicating more serious drinking. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test is used for this variable

CVD-related diagnoses based on medical record review

Medication use ascertained from the medical record include any current use of antipsychotic medications, antidepressants, or mood stabilizing medications

At baseline (Table 3), overall health-related quality of life scores were on average substantially lower (17 points) than the national norms (50 points) for the VR-12 component scores, Furthermore, the mean BMI was 33, in which a BMI of >30 is the definition of obesity. There were no statistically significant differences in baseline demographic characteristics (age, gender, race, college education, living alone) between participants who remained in the analysis at 12 months compared those who did not complete 12 month follow up survey.

Table 3.

Differences in Baseline Primary and Secondary Outcomes comparing Intervention (LG-CC) and Usual Care Groupsa

| Total (N =287) |

LG-CC (N=141) |

Usual care (N =146) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± sd or median (IQR) |

% | mean ± sd or median (IQR) |

% | mean ± sd or median (IQR) |

% | t |

p

-value |

|

| Primary outcome | ||||||||

| HRQOL physical health Score (VR-12)b |

33.3 ± 10.9 | 32.8 ± 10.9 | 33.9 ± 11.0 | .86 | .39 | |||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||

| HRQOL mental health Score (VR-12)b |

34.6 ± 12.1 | 35.5 ± 12.4 | 33.8 ± 11.8 | −1.23 | .21 | |||

| Systolic BP, mmHgc | 135.3 ± 14.5 | 135.7 ± 14.5 | 134.9 ± 14.5 | −.47 | .63 | |||

| Diastolic BP, mmHgc | 77.4 ± 9.8 | 76.8 ± 9.7 | 77.9 ± 9.9 | .92 | .35 | |||

| BMI, kg/m2d | 33.3 ± 6.2 | 34.3 ± 7.1 | 32.3 ± 5.2 | −2.71 | .007 | |||

| Physical activity (min/wk)e | 270.9 ± 287.1 | 167.5 ± 225.1 | 344.6 ± 305.5 | 2.78 | .006 | |||

| Psychiatric Symptoms | ||||||||

| Depression: PHQ-9f | 11.9 ± 5.9 | 11.5 ± 5.8 | 12.4 ± 6.0 | 1.34 | .18 | |||

| <10 | 36.4 | 40.7 | 32.2 | .31 | ||||

| 10-14 | 38.1 | 35.0 | 41.1 | |||||

| >=15 | 25.5 | 24.3 | 26.7 | |||||

| Psychosisg | .8 (.1, 1.7) | .7 (.1, 1.5) | .8 (.1, 1.8) | .24 | ||||

| Manic (activation)h | 20.4 ± 11.2 | 19.8 ± 11.1 | 20.9 ± 11.3 | .89 | .37 | |||

| Well-beingh | 16.5 ± 6.7 | 16.5 ± 6.7 | 16.4 ± 6.7 | −.07 | .94 | |||

| GAD | 9.4 ± 5.9 | 8.9 ± 5.8 | 9.7 ± 5.9 | 1.02 | .30 | |||

| PCL | 46.7 ± 16.5 | 45.2 ± 16.9 | 48.2 ± 16.0 | 1.48 | .14 | |||

| Framingham (FH) Scorei | 12.5 ± 7.8 | 12.6 ± 7.7 | 12.3 ± 7.9 | −.36 | .72 | |||

| FH < 10% | 36.2 | 35.7 | 36.8 | .97 | ||||

| FH 10-20% | 54.7 | 55.0 | 54.4 | |||||

| FH > 20% | 9.1 | 9.3 | 8.8 | |||||

| Lipids | ||||||||

| LDL | 11.3 ± 35.5 | 112.0 ± 36.5 | 110.6 ± 34.7 | −.34 | .73 | |||

| HDL | 41.5 ± 11.1 | 40.7 ± 10.3 | 42.3 ± 11.8 | 1.25 | .21 | |||

| Total cholesterol Waist Circumference, in.j |

184.2 ± 43.9 45.2 ± 6.1 |

182.1 ± 43.6 45.9 ± 6.6 |

186.2 ± 44.2 44.4 ± 5.4 |

.78 −2.13 |

.43 .03 |

Statistical method: Chi-squared test for categorical variables (% reported); Two independent samples t-test for numeric variables (mean ± sd reported); Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for the variables with a highly skewed distribution (median (IQR) reported).

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) was assessed from the patient survey using the 12-item Veterans Short-Form Health Survey (VR-12). Mental health (MCS) and physical health (PCS) component scores each ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better health

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were ascertained from a clinical assessment: based on the average of two blood pressure readings sitting down

Height and weight measurements to calculate body mass index (BMI) were ascertained from medical records and the clinical assessment, respectively

Physical activity was assessed via the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), which defines physical activity in # minutes per week based on 7-day self-report

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression symptom scale is a 9-item measure scored 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Scores <10 represent minimal symptoms, 10–14: dysthymia or mild depression, and >=15: moderate-severe depressive symptoms

Psychosis was assessed using a 5-item subscale of BASIS® measure; as a weighted sum of 4 items (scores range from 0-4), with a higher score indicating more severe symptoms. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test is used for this variable

Manic and well-being symptoms were assessed using the Internal State Scale (ISS), which includes scales for manic symptoms (scores range from 0 to 50, with higher score indicating more severe manic symptoms) and well-being (scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating great well-being)

Framingham Risk Scores: 3 risk categories estimate 10-year risk for coronary heart disease: high risk (>20%), moderately high risk (10%-20%), or lower to moderate risk (10-year risk <10%). The score was calculated based on the following variables: sex, age, Diabetic status, smoking status, total cholesterol, HDL, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure

Waist circumference was ascertained from the patient clinical assessment

Comparisons on baseline (pre-treatment) outcomes revealed significant differences in BMI, waist circumference, and physical activity between the intervention and control groups (Table 3) so these variables were included in the repeated measures analyses.

Table 4 presents repeated measures results which were estimates in the differences of changes from baseline to 12 months between patients randomized to either LG-CC or usual care. Overall, patients randomized to LG-CC compared to those randomized to usual care had a greater improvement, or difference in 12-month health-related quality of life VR-12 physical health component scores (β=3.21, p=0.01, Cohen’s d=0.39). There was a statistically significant reduction in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels for the LG-CC group compared to those from the usual care group (β =-8.77, p=0.04, Cohen’s d=-0.30).

Table 4.

12-Month Changes in Primary and Secondary Outcomes Comparing Participants Randomized to Life Goals Collaborative Care (LG-CC) or Usual Care (UC)a

| N=245 (includes those completing baseline and 12- month assessments) |

Life-goal(LG) N=124 |

Usual Care(UC) N=121 |

β, estimate of 12 month changes between LG and UC group (95% CI) |

Cohen’s D |

t-value | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Mean(SD) |

6 Month Mean(SD) |

12 month Mean(SD) |

Baseline Mean(SD) |

6 Month Mean(SD) |

12 month Mean(SD) |

|||||

| HRQOL physical health Score (VR-12)b |

32.41 (10.59) |

32.76 (11.89) |

33.61 (11.36) |

34.31 (10.92) |

33.54 (11.31) |

34.00 (11.49) |

3.21 (0.55-5.86) |

0.39 | 2.37 | 0.01 |

| HRQOL mental health Score (VR-12)c |

35.42 (12.23) |

38.25 (12.87) |

38.13 (12.41) |

34.49 (11.41) |

35.69 (10.97) |

36.36 (12.11) |

−0.004 (−3.38- 3.37) |

0.00 | −0.00 | 0.99 |

| Systolic BP, mmHgb | 135.39 (14.36) |

137.18 (17.74) |

135.95 (17.23) |

135.07 (14.58) |

136.37 (15.44) |

137.42 (16.95) |

−1.82 (−6.26-2.62) |

−0.12 | −0.80 | 0.42 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHgb | 76.44 (8.74) |

76.14 (10.28) |

75.46 (9.05) |

77.71 (9.69) |

77.61 (9.83) |

77.43 (9.32) |

−1.07 (−3.75-1.62) |

−0.11 | −0.78 | 0.43 |

| BMI, kg/m2d | 34.01 (6.74) |

34.38 (6.56) |

34.07 (6.98) |

32.48 (5.26) |

32.79 (5.66) |

32.76 (5.55) |

−0.50 (−1.05-0.05) |

−0.27 | −1.80 | 0.07 |

| Physical Activity (Minutes per week)e |

1212.61 (1776.04) |

1583.09 (2222.08) |

1494.50 (1927.02) |

1294.25 (1538.96) |

1492.99 (1943.34) |

1230.77 (1617.59) |

364.54 (−240.9-970.1) |

0.18 | 1.18 | 0.23 |

| Depressive symptoms (PHQ- 9 Score)f |

11.39 (5.67) |

9.99 (6.33) |

9.53 (6.19) |

12.06 (5.78) |

10.74 (5.44) |

11.26 (6.04) |

−0.73 (−2.35-0.89) |

−0.13 | −0.88 | 0.37 |

| ISS Activation scoreg | 19.53 (10.86) |

20.37 (11.70) |

19.83 (11.65) |

21.05 (11.26) |

21.22 (11.59) |

21.51 (11.67) |

−0.73 (−4.13-2.66) |

−0.07 | −0.42 | 0.67 |

| ISS Wellbeing scoreg | 16.52 (6.53) |

17.18 (6.71) |

18.19 (6.51) |

16.73 (6.81) |

17.39 (6.31) |

17.45 (6.47) |

−0.29 (−2.29-1.71) |

−0.04 | −0.29 | 0.77 |

| GAD scoreh | 8.93 (5.84) |

7.55 (5.48) |

6.35 (5.39) |

9.42 (5.78) |

9.16 (5.75) |

8.86 (5.51) |

−1.48 (−3.10- 0.15) |

−0.28 | −1.78 | 0.07 |

| PTSD scorei | 45.42 (16.63) |

41.80 (16.52) |

39.85 (16.51) |

47.45 (15.48) |

44.95 (14.12) |

45.00 (14.12) |

−0.59 (−3.92-2.74) |

−0.05 | −0.35 | 0.72 |

| Overall BASIS-24 Symptom scorej |

1.63 (0.56) |

1.43 (0.60) |

1.38 (0.61) |

1.63 (0.64) |

1.56 (0.54) |

1.53 (0.57) |

−0.05 (−0.21-0.11) |

−0.09 | −0.60 | 0.55 |

| Framingham Risk scores (%)k |

12.59 (7.73) |

14.69 (10.19) |

12.84 (8.69) |

12.29 (7.95) |

13.13 (8.24) |

13.86 (9.88) |

−1.79 (−4.23-0.66) |

−0.26 | −1.43 | 0.15 |

| LDL (mg/dl) |

112.24 (35.52) |

112.13 (35.13) |

107.71 (34.18) |

110.57 (34.31) |

115.15 (38.10) |

112.84 (37.72) |

−8.77 (−17.25 to −0.29) |

−0.30 | −2.03 | 0.04 |

| HDL (mg/dl) |

40.90 (10.49) |

41.75 (10.69) |

42.24 (10.56) |

41.86 (11.73) |

41.45 (10.48) |

42.81 (11.15) |

0.72 (−1.54-2.98) |

0.09 | 0.62 | 0.53 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) |

182.65 (42.32) |

185.71 (42.11) |

179.47 (41.70) |

186.31 (45.50) |

187.99 (46.68) |

187.08 (46.52) |

−6.53 (−17.0-3.99) |

−0.18 | −1.22 | 0.22 |

| Waist circumferencel | 45.68 (6.37) |

45.96 (6.31) |

45.34 (6.91) |

44.59 (5.51) |

44.63 (5.74) |

44.38 (5.55) |

−0.02 (−0.78- 0.74) |

−0.01 | −0.06 | 0.95 |

All models used repeated measures analyses, adjusting for time (6, 12 months), the LG-CC intervention, interaction term LG-CC X time, baseline IPAQ minutes per week, and waist circumference

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) was assessed from the patient survey using the 12-item Veterans Short-Form Health Survey (VR-12). Mental health (MCS) and physical health (PCS) component scores each ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better health

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were ascertained from a clinical assessment: based on the average of two blood pressure readings sitting down

Height and weight measurements to calculate body mass index (BMI) were ascertained from medical records and the clinical assessment, respectively

Physical activity was assessed via the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), which defines physical activity in # minutes per week based on 7-day self-report

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression symptom scale is a 9-item measure scored 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Scores <10 represent minimal symptoms, 10–14: dysthymia or mild depression, and >=15: moderate-severe depressive symptoms

Manic and well-being symptoms were assessed using the Internal State Scale (ISS), which includes scales for manic symptoms (scores range from 0 to 50, with higher score indicating more severe manic symptoms) and well-being (scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating great well-being)

GAD is a 7-item self-report tool designed to screen for the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). Higher score represent greater symptom intensity

The PTSD PCL assesses Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms via a 17-item self-reported measure, where higher score is equivalent to more symptoms

Psychosis was assessed using a 5-item subscale of BASIS® measure; as a weighted sum of 4 items (scores range from 0-4), with a higher score indicating more severe symptoms. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test is used for this variable

Framingham Risk Scores: 3 risk categories estimate 10-year risk for coronary heart disease: high risk (>20%), moderately high risk (10%-20%), or lower to moderate risk (10-year risk <10%). The score was calculated based on the following variables: sex, age, Diabetic status, smoking status, total cholesterol, HDL, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure

Waist circumference was ascertained from the patient clinical assessment

DISCUSSION

Patients with chronic mental disorders and at least one CVD risk factor receiving LG-CC had a greater improvement in physical health-related quality of life after 12 months compared to those receiving usual care. These findings reflect similar results elsewhere in which Life Goals Collaborative Care compared to usual care improved physical health-related quality of life among patients with bipolar disorder.15-18 While this finding was statistically significant, the effect size was moderate (Cohen’s D=.39) and the actual change in points based on the Physical Health Component score was small. Previous studies23,24 based on the physical health-related quality of life measure found that a 7-point improvement in the physical health component score was strongly correlated with improvements in cardiovascular disease symptom-specific measures.23 Nonetheless the substantially low physical health-related quality of life scores in this patient population (e.g., 33-34 points on average, when the population norm is 50 points) was found in previous research to be associated with a clinically significant increased risk in cardiovascular disease-related mortality (2-3 fold increased risk).24

We did not find observed improvement in secondary outcomes, notably CVD risk factors. In a recent review, evidence suggests that more intensive interventions for a longer duration might be needed to achieve weight loss in persons with mental disorders (e.g., direct physical activity involvement, direct provision of healthier food).59 Life Goals was designed as a briefer intervention that primarily focused on implementing collaborative care model components, notably self-management skills, among patients with chronic mental disorders among existing teams of providers. In contrast, more intensive weight loss programs for persons with chronic mental disorders60,61 typically involved added investments in new provider teams62-65 or deployment of closely supervised diet or exercise regimens.66-68 Nonetheless, LG-CC did have an observed impact on physical health-related quality of life, which in turn can be an important functional milestone towards the adoption of healthier lifestyles.18

In addition, we did not find any impact of LG-CC on mental health outcomes. The lack of findings on mental health effects might have been due to the fact that patients in both the intervention and control groups were not only enrolled in outpatient mental health services but had access to psychotherapies in a VA clinic, including individual and group therapy. Moreover, the LG-CC intervention was focused mainly on mitigating physical health risk.

There are limitations to this study that warrant consideration. The intervention was evaluated in a single VA site so generalizability may not extend to sites beyond Midwestern VA mental health clinics.69 The inclusion criteria were broad (with the inclusion of different CVD risk factors) in order to closely resemble a real-world clinic population, which may have also led to heterogeneity in the sample and limited impact on outcomes or significance in findings. Still, the persistent level of CVD risk factors has been observed elsewhere in non-VA settings.70 In addition, the study relied on a single interventionist with a health education background. While consistent results were found in previous LG-CC studies utilizing interventionists with nursing, psychology, and other medical backgrounds,12,16,17,32 it is possible that the study results were influenced by the individual characteristics of the interventionist. There was insufficient information on diet and medication use to determine the mechanisms by which LG-CC might have contributed to changes in LDL levels. There were also questions regarding whether the usual care group received any of the LG-CC components, notably through patients’ providers who might have had another patient in the LG-CC group. Diagnoses based on ICD-9 codes to identify those with mental disorder were not confirmed by clinician diagnostic confirmation. Finally, only self-completed physical activity measures were included and no direct observation of health behaviors such as physical activity.

Overall, LG-CC compared to usual care produced modest improvements in physical health-related quality of life and had no effect on specific CVD-related outcomes with the exception of LDL levels. Despite the dissemination of guidelines to manage CVD risk factors,40 outcomes remain suboptimal for persons with chronic mental disorders. Moreover, the consistently low health-related quality of life scores suggest that this population is particularly vulnerable to poor CVD-related outcomes. The VA is one of the largest providers of care for patients with chronic mental disorders across the U.S. and thus results will have implications for improving care for this group. Interventions such as Life Goals Collaborative Care that are driven by patient self-management approaches may improve overall health in this group. Further studies are needed to determine whether changes in quality of life lead to long-term effects on morbidity or mortality.

Clinical Points.

Collaborative Care Models (CCMs) provide proactive care for patients through self-management education and ongoing care coordination with providers, but have not been evaluated in a diverse patient population with mental disorders.

CCMs may improve health-related quality of life for persons with chronic mental disorders, but more support might be needed to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service, Washington D.C. (IIR 10-340) and (RRP 10 226). The funding agency had no role in the decision to publish study results.

Footnotes

Indications of previous presentations: Study outcomes were presented as posters at the University of Michigan Health System Social Work Research Symposium in Ann Arbor, MI on October 8, 2015, the VA Health Services Research and Development Annual Meeting in Philadelphia, PA on July 9, 2015, and the 26th Annual Albert J. Silverman Research Conference hosted by the Department of Psychiatry, University Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor, MI on May 27, 2015.

Disclaimer statements: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. AMK and MSB are authors of the workbook, “Overcoming Bipolar Disorder: A Comprehensive Workbook for Managing Your Symptoms & Achieving Your Life Goals” (New Harbinger Publications, Inc., 2008) which was the basis for many of the current study intervention materials and receive publication royalties. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01487668 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01487668) and NCT01244854 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01244854)

REFERENCES

- 1.Schinnar AP, Rothbard AB, Kanter R, Jung YS. An empirical literature review of definitions of severe and persistent mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147(12):1602–1608. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.12.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilbourne AM, Ignacio RV, Kim HM, Blow FC. Datapoints: are VA patients with serious mental illness dying younger? Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(5):589. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells KB, Miranda J, Gonzalez JJ, Workgroup NAD. Overcoming barriers and creating opportunities to reduce burden of affective disorders: a new research agenda. Ment Health Serv Res. 2002;4(4):175–178. doi: 10.1023/a:1020947829820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334–41. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilbourne AM, Cornelius JR, Han X, et al. General-medical conditions in older patients with serious mental illness. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(3):250–254. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kilbourne AM, Morden NE, Austin K, et al. Excess heart-disease-related mortality in a national study of patients with mental disorders: identifying modifiable risk factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horvitz-Lennon M, Kilbourne AM, Pincus HA. From silos to bridges: meeting the general health care needs of adults with severe mental illnesses. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25(3):659–669. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kilbourne AM, Welsh D, McCarthy JF, Post EP, Blow FC. Quality of care for cardiovascular disease-related conditions in patients with and without mental disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1628–1633. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0720-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):216–226. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kilbourne AM, Brar JS, Drayer RA, Xu X, Post EP. Cardiovascular disease and metabolic risk factors in male patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(5):412–417. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.5.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, Georges H, Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(8):790–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11111616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, et al. Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, et al. Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: Part II. Impact on clinical outcome, function, and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(7):937–945. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Bauer MS, Unutzer J, Operskalski B. Long-term effectiveness and cost of a systematic care program for bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):500–508. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilbourne AM, Goodrich DE, Lai Z, et al. Randomized controlled trial to assess reduction of cardiovascular disease risk in patients with bipolar disorder: the Self-Management Addressing Heart Risk Trial (SMAHRT) J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(7):e655–662. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Nossek A, Drill L, Cooley S, Bauer MS. Improving medical and psychiatric outcomes among individuals with bipolar disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(7):760–768. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.7.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selim AJ, Rogers W, Fleishman JA, et al. Updated U.S. population standard for the Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey (VR-12) Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):43–52. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9418-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kazis LE, Selim A, Rogers W, Ren XS, Lee A, Miller DR. Dissemination of methods and results from the veterans health study: final comments and implications for future monitoring strategies within and outside the veterans healthcare system. J Ambul Care Manage. 2006;29(4):310–319. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200610000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hays RD, Hahn H, Marshall G. Use of the SF-36 and other health-related quality of life measures to assess persons with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:S4–9. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.36837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware J, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wyrwich KW, Nienaber NA, Tierney WM, Wolinsky FD. Linking clinical relevance and statistical significance in evaluating intra-individual changes in health-related quality of life. Med Care. 1999;37(5):469–78. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosworth HB, Siegler IC, Brummett BH, et al. The association between self-rated health and mortality in a well-characterized sample of coronary artery disease patients. Med Care. 1999;37:1226–36. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97(18):1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilbourne AM, Bramlet M, Barbaresso MM, et al. SMI life goals: description of a randomized trial of a collaborative care model to improve outcomes for persons with serious mental illness. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;39(1):74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blow FC, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Bowersox NW, Visnic S. Care for Veterans with Psychosis in the Veterans Health Administration, FY10: 12th Annual National Psychosis Registry Report; Ann Arbor, MI. VA Serious Mental Illness Treatment Resource and Evaluation Center (SMITREC); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodrich DE, Kilbourne AM, Lai Z, et al. Design and rationale of a randomized controlled trial to reduce cardiovascular disease risk for patients with bipolar disorder. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(4):666–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauer MS, Lee A, Miller CJ, Bajor L, Li M, Penfold RB. Effects of diagnostic inclusion criteria on prevalence and population characteristics in database research. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;1(66):141–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blow FC, Zeber JE, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Gillon L, Bingham CR. Ethnicity and diagnostic patterns in veterans with psychoses. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:841–51. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0824-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Report From the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, et al. Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: part I. Intervention and implementation in a randomized effectiveness trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(7):927–936. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon GE, Ludman E, Unutzer J, Bauer MS. Design and implementation of a randomized trial evaluating systematic care for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4(4):226–236. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Nossek A, et al. Service delivery in older patients with bipolar disorder: a review and development of a medical care model. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(6):672–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: A decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bauer MS, McBride L. Structured Group Psychotherapy for Bipolar Disorder: The Life Goals Program. 2nd Springer Publishing Co.; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. 2nd Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Mental Illness Treatment Research and Evaluation Center (MIRECC) Clinical practice and formulary guidelines: MIRECC Initiative on Antipsychotic Management Improvement [MIAMI] 2011 [cited 2011 May 1]; Available from: http://vaww.mirecc.va.gov/miamiproject/guidelines.asp.

- 41.Kilbourne AM, Goodrich DE, Nord KM, et al. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes from a Randomized Controlled Trial of Two Implementation Strategies to Promote Collaborative Care Attendance in Community Practices. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0598-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waxmonsky J, Kilbourne AM, Goodrich DE, et al. Enhanced fidelity to treatment for bipolar disorder: results from a randomized controlled implementation trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(1):81–90. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faulkner G, Cohn T, Remington G. Validation of a physical activity assessment tool for individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;82(2-3):225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young AS, Niv N, Chinman M, et al. Routine outcomes monitoring to support improving care for schizophrenia: report from the VA Mental Health QUERI. Community Ment Health J. 2011;47(2):123–135. doi: 10.1007/s10597-010-9328-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bauer MS, Vojta C, Kinosian B, Altshuler L, Glick H. The Internal State Scale: replication of its discriminating abilities in a multisite, public sector sample. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2(4):340–346. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.020409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glick HA, McBride L, Bauer MS. A manic-depressive symptom self-report in optical scanable format. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5(5):366–369. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eisen SV, Normand SL, Belanger AJ, Spiro A, Esch D. The Revised Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-R): reliability and validity. Med Care. (3rd) 2004;42(12):1230–1241. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conybeare D, Behar E, Solomon A, Newman MG, Borkovec TD. The PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version: reliability, validity, and factor structure in a nonclinical sample. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68(6):699–713. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilkins KC, Lang AJ, Norman SB. Synthesis of the psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) military, civilian, and specific versions. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(7):596–606. doi: 10.1002/da.20837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fenn HH, Bauer MS, Altshuler L, et al. Medical comorbidity and health-related quality of life in bipolar disorder across the adult age span. J Affect Disord. 2005;86(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Bauer MS, et al. Therapeutic drug and cardiovascular disease risk monitoring in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1-3):145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1968;16(5):622–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Conwell Y, Forbes NT, Cox C, Caine ED. Validation of a measure of physical illness burden at autopsy: the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(1):38–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb05945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS. The AUDIT-C: screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the presence of other psychiatric disorders. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2005;46(6):405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kilbourne AM, Nord KM, Kyle J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a health plan-level mood disorders psychosocial intervention for solo or small practices. BMC Psychol. 2014;2(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s40359-014-0048-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ward MC, White DT, Druss BG. A meta-review of lifestyle interventions for cardiovascular risk factors in the general medical population: lessons for individuals with serious mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(4):e477–486. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gierisch JM, Nieuwsma JA, Bradford DW, et al. Pharmacologic and behavioral interventions to improve cardiovascular risk factors in adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(5):e424–440. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Siantz E, Aranda MP. Chronic disease self-management interventions for adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review of the literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Compton MT, Rask KJ, Zhao L, Parker RM. A randomized trial of medical care management for community mental health settings: the Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):151–159. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morgan MA, Coates MJ, Dunbar JA, Reddy P, Schlicht K, Fuller J. The TrueBlue model of collaborative care using practice nurses as case managers for depression alongside diabetes or heart disease: a randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Druss BG, Zhao L, von Esenwein SA, et al. The Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) Program: a peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr Res. 2010;118(1-3):264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bartels SJ, Aschbrenner KA, Rolin SA, Hendrick DC, Naslund JA, Faber MJ. Activating older adults with serious mental illness for collaborative primary care visits. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2013;36(4):278–288. doi: 10.1037/prj0000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bartels SJ, Pratt SI, Aschbrenner KA, et al. Pragmatic replication trial of health promotion coaching for obesity in serious mental illness and maintenance of outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;AiA:1–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14030357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Daumit GL, Dickerson FB, Wang NY, et al. A behavioral weight-loss intervention in persons with serious mental illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1594–1602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Green CA, Yarborough BJ, Leo MC, et al. The STRIDE weight loss and lifestyle intervention for individuals taking antipsychotic medications: a randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):71–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kilbourne AM, Goodrich D, Miklowitz DJ, Austin K, Post EP, Bauer MS. Characteristics of patients with bipolar disorder managed in VA primary care or specialty mental health care settings. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(5):500–507. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.5.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Druss BG, Zhao L, Cummings JR, Shim RS, Rust GS, Marcus SC. Mental comorbidity and quality of diabetes care under Medicaid: a 50-state analysis. Med Care. 2012;50(5):428–433. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]