Abstract

Sexual minority adolescents (lesbian, gay, bisexual) experience disparities in behavioral health outcomes compared to their heterosexual peers, generally attributed to minority stress. Although evidence of the applicability of the minority stress model among adolescents exists, it is based on a primarily adult literature. Developmental and generational differences demand further examination of minority stress to confirm its applicability. Forty-eight life history interviews with sexual minority adolescents in California (age 14–19; M=19.27 SD = 1.38; 39.6% cismale, 35.4% cisfemale, 25% other gender) were completed, recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using thematic analysis in QSR NVivo. Following a consensus model, all transcripts were double coded. Results suggest that minority stress is appropriate for use with adolescents; however, further emphasis should be placed on social context, coping resources, and developmental processes regarding identity development. A conceptual model is provided, as are implications for research and practice.

Sexual minority adolescents (lesbian, gay, bisexual) experience disparities in behavioral health outcomes compared to their heterosexual peers. For example, sexual minority adolescents are 3 to 4 times more likely to meet criteria for an internalizing disorder and 2 to 5 times more likely to meet criteria for externalizing disorders than their heterosexual peers (Fergusson, Horwood, & Beautrais, 1999). This includes higher rates of internalizing psychopathology such as depression, anxiety, and self-harm (Anhalt & Morris, 1998; Haas et al., 2010; Hendricks & Testa, 2012) and substance use (Marshal, Friedman, Stall & Thompson, 2009). Sexual minority adolescents are more than twice as likely to have attempted suicide compared to their heterosexual peers (Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Russell & Joyner, 2001; Schulenberg, Maggs, Steinman, & Zucker, 2001). A recent meta-analysis found sexual minority adolescents are almost 3 times more likely to report a history of suicidality and 5 times more likely to make an attempt than their peers (Marshal et al., 2011). These youth also more frequently report lower academic achievement (D’Augelli, Pilkington, & Hershberger, 2002; Kosciw, Greytak, Bartkiewicz, Boesen, & Palmer, 2012; Poteat et al., 2014) and higher rates of eating disorders and obesity (Austin, Nelson, Birkett, Calzo, & Everett, 2013) than their heterosexual peers. When these disparities occur in adolescence, they can negatively influence a lifelong trajectory of health (Baer, 1993). Therefore, identifying appropriate clinical intervention points is critical.

Minority stress

Research has linked the disparate mental health outcomes found among sexual minorities to unique stressors (Alessi, Martin, Gyamerah, & Meyer, 2013; Goldbach, Schrager, Dunlap, & Holloway, 2015; Goldbach, Tanner-Smith, Bagwell, & Dunlap, 2014; Steinberg & Morris, 2001), commonly known as minority stress (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009; Meyer, 2003; Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Gwadz, 2002). Minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) is by far the most widely applied explanatory model for this phenomenon, and posits that an array of unique and chronic psychosocial stressors affects sexual minorities and contributes to negative behavioral health patterns.

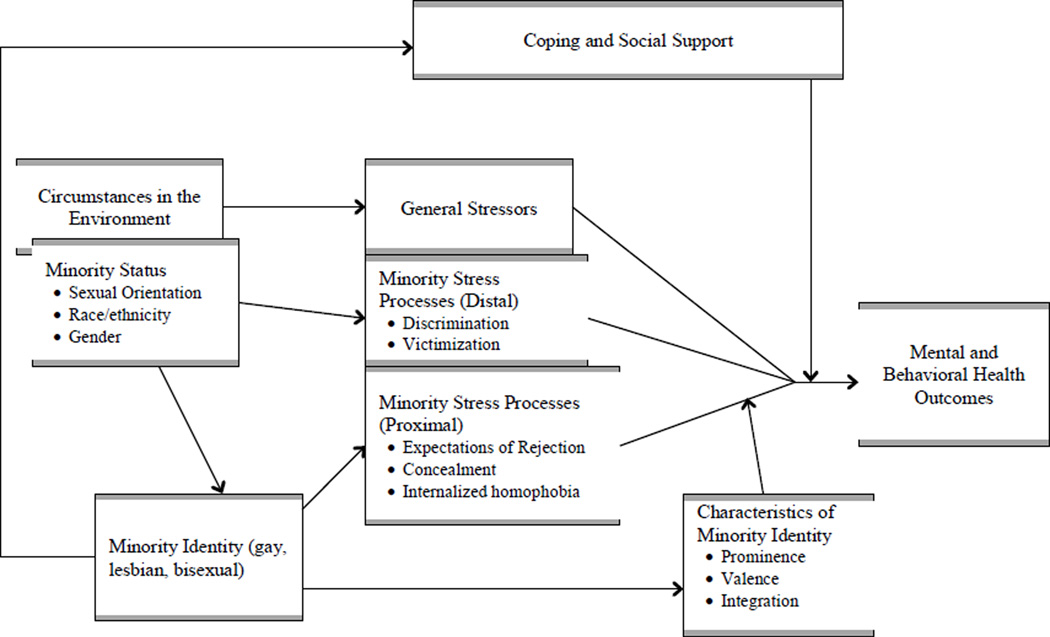

As shown in Figure 1 (Meyer, 2003; pp. 679), minority stress theory considers how stress affects an individual’s mental health outcomes. First, the theory posits that general circumstances in the environment (including socioeconomic circumstances and living conditions) and minority status (including sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, and gender) are interconnected. As Meyer (2003) explained, “circumstances in the environment lead to exposure to stressors, including general stressors, such as a job loss or death of an intimate [partner], and minority stressors unique to minority group members, such as discrimination in employment. Similar to their source circumstances, the stressors are depicted as overlapping as well, representing their interdependency” (p. 678).

Figure 1.

Minority stress processes in lesbian, gay and bisexual populations1

1Reprinted with permission per APA guidelines from Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, p. 694.

Minority stressors

In addition to these general factors, individuals are exposed to three sets of stressors. First, general stressors in the environment influence mental health, such as job loss, death of a loved one, etc. It is important to note that general stressors may be exacerbated through minority stress. For example, losing a job is difficult, but losing a job because you disclose your sexual orientation and experience discrimination by your employer is hypothesized to influence mental health beyond that of job loss alone. Individuals in a minority group (in this case, sexual minorities) are also further affected by two sets of minority-related stressors. These include both distal stressors in the environment (i.e., prejudicial events, discrimination, and violence) and proximal stressors internal to the individual (i.e., expectations of rejection, concealment, and internalized homophobia). Research has suggested that these factors are chronic and unique in their contribution to mental health (Rosario et al., 2002). It is important to note that these factors are interrelated and bidirectional. For example, having a negative disclosure experience (distal) may increase expectations of rejection (proximal). At the same time, concealing one’s identity due to rejection expectations (proximal) may reduce the likelihood of victimization; research has suggested that disclosing a sexual minority identity, or “being out,” to more individuals is correlated with higher rates of violence and victimization (Chesir-Teran & Hughes, 2009; Kosciw, Palmer, & Kull, 2015).

Coping

Although these stressors together influence behavioral health outcomes, they are interrupted (moderated) by (a) the presence of coping and social supports including group solidarity, enhanced in-group identity, and affirming communities; and (b) the characteristics of the minority identity, which include how prominent and important the minority identity is to the participant. Coping (or stress-ameliorating factors; Meyer, 2003) and resilience can occur on the personal level (individual dependent; e.g., enhanced in-group minority identity) and the group level (e.g., in-group reappraisal of stressful events or a gay-affirming church). Further, when group-level coping mechanisms are absent, minority individuals have more difficulty coping because they cannot engage identity-stabilizing external factors. In some instances, the coping strategy employed at the individual level may also have unintentional detrimental effects. For example, coping by concealing one’s sexual identity may help in avoiding negative discriminatory experiences (distal) but may also have a negative impact on an individual’s psyche (proximal).

Characteristics of the minority identity

Finally, the impact of these experiences on a lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) individual’s mental health also influences and is influenced by self-perceptions of the individual’s minority identity; that is, how strongly the individual identifies as part of a minority community. In short, if an individual is exposed to a minority stressor (e.g., called a discriminatory name) but does not identify strongly with that identity, it is perhaps less likely to affect that individual’s mental health patterns.

Minority stress: an appropriate model for adolescence?

Although studies (including meta-analyses) have added evidence to the applicability of the minority stress theory to adolescents (e.g., Friedman et al., 2011; Goldbach et al., 2014; Shilo, Antebi, & Mor, 2015), scholars have noted a reliance on adult or young adult samples (e.g., Kelleher, 2009; Shilo & Savaya, 2012) and lack of attention to other non-LGBT-related mediating factors (e.g., developmental influences, emotional dysregulation, cognitive processes; Herts, McLaughlin & Hatzenbuehler, 2012). The disproportionate attention to adult samples in sexual minority research (particularly young men who have sex with men) has been described elsewhere (e.g., Institute of Medicine, 2011). Examining minority stress theory prospectively from an adolescent perspective is needed. In particular, it is important to consider: (a) identity developmental processes in adolescence; (b) the nature of minority stress during adolescence; and (c) the changing experience of coping and social support among young sexual minority adolescents in the current context.

Identity development

Attention to minority stress during adolescence is essential, because stigmatizing experiences during this time are known to disrupt the achievement of developmental tasks and contribute to negative outcomes later in life (Radkowsky & Siegel, 1997). That is, minority stress experiences during adolescence may have an enduring impact on mental health into adulthood (Gibbs & Rice, 2016). From a developmental framework, adolescence is a critical period during which individuals establish long-term trajectories of health and are often still solidifying their sexual identities (Mustanski, Kuper, & Greene, 2013). Some sexual orientation fluidity in adulthood has been documented (e.g., Tolman & Diamond, 2001), although sexual identities tend to remain stable (Mock & Eibach, 2011). However, for adolescents (including general population youth), sexuality and identity development is a central task (Erikson, 1968), and the articulation of attractions, labels, behaviors, and expressions are noteworthy (Goldbach & Gibbs, 2015; Rusow et al., 2015). Because many sexual minority adolescents appear to “try on” a variety of identity labels as they seek congruence with their sexual identity (e.g., identify as bisexual or pansexual, then gay or lesbian; Rusow et al., 2015), this process may itself be an internal (proximal) stressor. As described in the original minority stress theory, how individuals perceive their membership to a minority community and identity can influence their interpretation of minority stress (i.e., characteristics of minority identity). Thus, if adolescents are unsure of their identity or that label often changes, it may have a differential impact on their mental health outcomes. To our knowledge, only a small handful of studies (see Russell, Clarke, & Clary, 2009) have begun to examine emerging identity characteristics (e.g., pansexual, queer) among samples of sexual minority adolescents, with little attention to this identity development as a potential form of minority stress.

Minority stressors

The exact distal and proximal minority stress experiences that sexual minority adolescents encounter may also differ in relevant ways from their adult counterparts. For example, these youth often report disclosure-related stress in the context of two compulsory social environments that adults do not; that is, living at home with family and attending primary school (D’Augelli, 2006; Goldbach et al., 2014; Rice et al., 2014; Russell, Franz, & Driscoll, 2001). Negative parental reactions to adolescents’ disclosure can create stress in the home in which they live, with significant consequences including homelessness (Clatts, Goldsamt, Yi, & Gwadz, 2005; Rice et al., 2014; Rosario et al., 2002). This is particularly salient because most adolescents rely on the financial support of their family to ensure stability. In-school victimization (i.e., bullying) by other students and teachers is also increasingly of concern (Russell, Ryan, Toomey, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2011; Toomey, Ryan, Diaz, Card, & Russell, 2010), and many sexual minority adolescents attend schools in which homophobic bullying is common and teachers do not readily intervene (Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network, 2012). Youth who are (or are perceived to be) a sexual minority are more likely to be bullied in school, which has been correlated with high rates of absenteeism, lower educational attainment, depression, and suicidality (Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network, 2012; Ybarra, Mitchell, Kosciw, & Korchmaros, 2015). Similarly, structural factors that are out of an adolescent’s control (e.g., legal requirements to attend school, inability to secure emancipation from parents) may contribute to poorer mental health patterns among sexual minority adolescents (Goldbach & Gibbs, 2015; Hatzenbuehler, 2011). We contend that special attention may be warranted in considering minority stress in an adolescent’s lived experience as unique from that of adults.

Coping and social support

Finally, coping processes may also be different for youth today than in 2003. The world, and specifically in the present study the United States, is a different place for sexual minorities than it was more than a decade ago. With the passage of hate crime legislation in 2009, which applies harsher punishments for crimes motivated by hate toward LGBT people in the United States (Matthew Sheppard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crime Act of 2009); the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell in 2010 and subsequent policy changes for transgender service in 2016 that now allows LGBT service members to serve openly in the U.S. Military; the passage of federal marriage equality in 2015 across the United States (Obergefell v. Hodges, 2015); and the passage of more than 30 state employment-based LGBT protection laws in the U.S. (Hunt, 2012), sexual minority adolescents are maturing in a society that views LGBT people very differently. In fact, in Meyer’s (2003) discussion of personal and group resources, he illustrated the interaction between these factors using Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell in the U.S. military as an example. As he accurately stated in 2003, this policy actively “discouraged affiliation and attachments with other LGB persons [making a service member] unable to access and use group-level resources regardless of his or her personal coping abilities” (Meyer, 2003, p. 677). In general, public opinion on same-sex couples has changed dramatically in the past 12 years; in December 2003, an estimated 31% of the US. population supported marriage equality, compared to 61% in 2015 (Gallup, 2016).

Given these changes, it is conceivable that many sexual minority adolescents now mature in social environments in which being a sexual minority is not perceived negatively or in some cases even seen as positive. Further, although sexual minority adolescents may still experience minority stressors, they may also be able to easily access new coping resources (i.e., social or personal tools in a social environment that can be used to cope; Compas, Conner-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001) not readily available to previous generations. These coping resources may include supportive teachers, a supportive parent, a school gay–straight alliance, and supportive straight peers (Goldbach & Gibbs, 2015).

Given this background, the present study was guided by a central question: Does the minority stress theory apply to sexual minority adolescents? Although this research is exploratory, we expected that sexual minority adolescents would report experiencing both distal and proximal stressors related to their sexual identity given extant research documenting ongoing discrimination toward this population. However, we conceived that the aforementioned factors may be influential in understanding how the theory can be best applied to this population of high need.

Methods

Study sites

A formative assessment was conducted with support from a small intramural university grant and involved interviews with 25 key informants. The assessment was conducted at three local social service organizations that cater to a large number of sexual minority adolescents. Based on findings from the formative process, it was determined that recruitment for interviews with youth should occur at three agencies and one school site. These locations were selected in part because they serve racial and ethnically diverse youth in geographically unique settings. Together, the included agencies directly serve more than 3,000 sexual minority adolescents each year, more than 50% of whom identify as a racial or ethnic minority.

Interview participants

An initial set of 54 youth were invited for participation using a purposive strategy known as maximum variation sampling, which captures heterogeneity across a sample population (Patton, 2001). The intention was to include youth from diverse sexual orientation, gender, and racial and ethnic groups. To participate in the present study, youth were required to (a) be 13 to 19 years old (adolescents); (b) speak English or Spanish; (c) self-identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or an alternate nonheterosexual identification; and (d) be willing and able to provide verbal assent. Because LGBT adolescents constitute a vulnerable population and some individuals in their network (parents, friends) may not be aware of their sexual or gender minority status, written consent was waived by the institutional review board. Of the 54 sexual minority adolescents invited, 52 completed the interview and 48 were included in the final analysis. Two participants were excluded because they did not meet study inclusion criteria (i.e., identified as heterosexual) and four were excluded because they were older than 19 at the time of the interview. If during the course of the interview a participant identified with a gender minority status (e.g., transgender, gender nonconforming, gender queer), they were still included in the analysis; however, all participants identified as a sexual minority.

Recruitment and procedures

During a 3-month period, the principal investigator and bilingual research assistants were made available in private offices provided by the participating agency partners for drop-in hours and appointments set for youth through agency partners. Agency staff members conducted a preliminary screening of participants based on inclusion criteria and referred eligible individuals to meet with a member of the research team. After an introduction, the interviewer privately reviewed a consent form and asked for verbal agreement. Interviews were audio recorded and followed a semistructured life history calendar protocol. During the interviews, interviewers summarized respondent comments on a question-by-question basis to aid in analysis. Interviews lasted approximately 90 minutes, and youth were offered a $20 incentive for participation and as many as three $5 incentives for referring additional youth.

Instrument

Given our emphasis on the importance of developmental processes, the semi-structured interview was guided by a life history calendar (Caspi et al., 1996) approach, which encourages participants to identify salient life experiences related to growing up, including reflection on periods both before and after disclosing their sexual identity (i.e., coming out) to various people (parents, friends); significant moments in their life (e.g., first kiss with an individual of the same or other sex); and the potentially dynamic effect of these experiences on psychosocial stress and well-being over time. The chronological structure of our approach was intended to increase participants’ ability to recall events and associated feelings (Caspi et al., 1996) and to acknowledge the fluid and developing aspects of sexual identity formation (Diamond, 1998). Further, the life history approach is appropriate for research topics focusing on populations that have experienced significant trauma or represent a stigmatized group (Harold, Palmiter, Lynch, & Freedman-Doan, 1995) and has been successfully used in other studies involving racially and ethnically diverse youth (Chanmugam, 2011) and sexual minority adolescents (Fisher, 2012; Fisher & Boudreau, 2014).

The life history calendar used in the present study was developed in an Excel worksheet, printed on poster-size paper, and laminated so that participants could draw, write, or otherwise note their responses as they spoke with the interviewer. The calendar was organized with years across the top row, with the current year listed at the far left and counting down for 15 years. Key statements about stress domains were listed along the first column.

To build the list of key stress statements, the research team relied on the extant literature on both domains of minority stress (e.g., Goldbach et al., 2014; Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Meyer, 2003) and existing instruments used in previous research. This process identified an initial set of nearly 200 questions related to sexual and gender identity development, life experiences, and stress commonly found among sexual minority adolescents that had been asked in prior studies. After removing duplicate questions, we organized these questions into nine key domains (life landmarks; sexual minority milestones; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer expressions; home life; peer group; school; spirituality; race and ethnicity; and community connection).

To support the interview process, an interview protocol was developed to both guide the interviewer and provide probing questions to support the inquiry of each domain. For example, although the calendar displayed only “Home life: How it is at home?” and “Home life: Reactions and responses,” the interview guide included both an initial probing question of “What is your life like at home or with your family?” and subsequent probes such as “How has this changed over time?” and “What reactions have you gotten from individual people because of being LGBT?” After a draft of the calendar and the interview protocol was developed, it was sent to a panel of recognized experts in the field of LGBT behavioral health for feedback. Based on expert consultant feedback, the protocol was further refined to include additional probes, presented to agency partners for approval, and finalized for use.

Analysis

The recordings from interviews were transcribed verbatim and entered into QSR NVivo. Because our interest was testing and refining minority stress theory with consideration of the three aforementioned concerns (i.e., development, adolescent-specific experiences, and social support), we relied on a methodology rooted in grounded theory (Glaser, 1978); i.e., theory derived from data and illustrated by characteristic examples of data. Thematic analysis was conducted following a process outlined by Boyatzis (1998). This consisted of (a) generating codes to be attached to similar quotes or topics across transcripts for data reduction; (b) revising codes to become themes that fit with the nature of the data by comparing similar ideas across transcripts; and (c) determining the reliability of codes and themes by identifying both positive and negative examples of qualifications. Two coders independently determined codes to be attached to text fragments representing descriptions or evaluations of stressors and coping processes. After the research team achieved consensus, with an overall interrater agreement of 92%, axial coding was used to reorganize specific text segments according to conceptual minority stress domains. These domains were inspected for conceptual fit with a priori domains identified by the expert panel and previous research (Goldbach et al., 2014; Meyer, 2003) and grouped using minority stress theory as a sensitizing framework. Additional domains were identified with items that did not fit in the original model.

Results

Respondents on average were 16.27 years old (SD = 1.38). Most respondents were enrolled in high school (92%). The majority of the sample identified as cisgender (i.e., 40% male and 35% female), with a minority of participants identifying as transgender or queer (25%). Sexual orientation identification varied, with 40% identifying as gay or lesbian, 27% as bisexual, 17% as pansexual, and 17% as other. Participants reported diverse primary racial and ethnic identifications: 40% Latino, 25% White or Caucasian, 21% Asian, and 1% Black or African American. In addition to a primary racial and ethnic identification, a sizable minority of participants also identified as multiracial (27%). Table 1 provides detailed demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 48).

| n or M | % or SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 16.27 | 1.38 |

| 14 | 4 | 8.30 |

| 15 | 12 | 25.00 |

| 16 | 11 | 22.90 |

| 17 | 13 | 27.10 |

| 18 | 4 | 8.30 |

| 19 | 4 | 8.30 |

| Gender | ||

| Cismale | 19 | 39.60 |

| Cisfemale | 17 | 35.40 |

| Transmale | 7 | 14.60 |

| Transfemale | 2 | 4.20 |

| Queer | 3 | 6.30 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Gay | 12 | 25.00 |

| Lesbian | 7 | 14.60 |

| Bisexual | 13 | 27.10 |

| Pansexual | 8 | 16.70 |

| Asexual | 1 | 2.10 |

| Other | 7 | 14.60 |

| Race | ||

| Latino | 19 | 39.60 |

| African American | 7 | 14.60 |

| White | 12 | 25.00 |

| Asian | 10 | 20.80 |

| Mixed race | 13 | 27.10 |

| Grade | ||

| 9th | 9 | 18.80 |

| 10th | 9 | 18.80 |

| 11th | 14 | 29.20 |

| 12th | 12 | 25.00 |

| College | 2 | 4.20 |

| Not in school | 2 | 4.20 |

Key findings were first examined with regard to their fit with the original minority stress theory. Findings that did not fit with the original theory were largely related to: (a) the importance of social context in understanding minority stress; (b) the presence of context-dependent coping resources; and (c) the importance of considering identity development during adolescence.

Model fit: Minority Stress Theory

All participants reported experiencing some form of minority stress as presented in the original model (Meyer, 2003). These stressors were categorized as distal (discrimination and victimization), proximal (expectations of rejection and internalized stigma such as homophobia), and disclosure (concealment stress). Participants discussed more than 30 unique experiences of sexual minority discrimination, including overt experiences of discrimination (e.g., having family members, friends, and teachers disapprove of the participant being a sexual minority, losing friendships due to being a sexual minority, and peers refusing to engage in school activities with the participant because of sexual minority status) and proxy experiences of discrimination (e.g., seeing other sexual minority peers discriminated against and hearing anti-LGBT messages at church). In many cases, participants also reported violence (i.e., verbal and physical) as a result of the discrimination they experienced. Participants discussed experiencing verbal and social victimization (e.g., derogatory names, threats of physical altercations, rumors about their sexuality, jokes about them being a sexual minority adolescent) and physical violence (e.g., stabbed by a peer, choked by a parent, beaten by a group of kids) because of their sexual minority status.

Participants also discussed the stress of internalized stigma related to being a sexual minority, consistent with minority stress theory. Youth reported how being perceived as being gay caused internal stress:

“[Other students] were like, ‘Oh, you’re gay?’ … and I was like, ‘Am I?’ And then I’m like, ‘No, I’m not. No, I’m not. I don’t want to be.’ And then it was like if someone would be like, ‘Oh, you’re gay,’ I would just turn my head and walk away from them.” (cismale, African American, pansexual, 15)

Participants also pressured themselves to behave in heteronormative ways (that is, trying to behave in a manner reflective of being heterosexual) because being a sexual minority was perceived as unacceptable. One male participant recounted how he would criticize himself for his same-sex attraction: “I started [to] kind of like develop emotions toward other guys … and I always grew up thinking that gays were bad and an abomination, if you would. I always grew up thinking that so I would always bash myself” (cismale, Asian, gay, 16). In addition to managing distal and proximal stressors, youth commonly reported having to manage disclosing their sexual identity to others, which included stress related to concealment and not knowing how to disclose their status.

Also consistent with minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003), participants reported coping strategies used to attenuate minority stress experience. Coping strategies ranged from leveraging LGBT connections (e.g., going to LGBT pride events, using LGBT online resources, going to an LGBT youth center, becoming involved in a gay–straight alliance) to conforming to heteronormative behaviors (e.g., dating individuals of the opposite sex, denying same-sex attraction).

Although minority stress experiences and coping strategies employed to manage these experiences appeared to fit with the original theory, three important themes emerged from the data that are not as clearly articulated in the model.

Distinctions in context and coping

When youth reported stress experiences, they discussed them as being dependent on social context. More specifically, the minority stress experiences (i.e., discrimination, victimization, expectations of rejection, internalized stigma, and disclosure decision-making) identified by youth occurred in six social contexts: family, school, peer and social media, religion, race and ethnic background, and the LGBT community.

Additionally, expanding from coping skills described at length by Meyer (2003), participants discussed coping resources (not described in the original model) that did not require active behavior but instead were simply characteristics of the six social contexts. Eighteen coping resources (e.g., supportive family members, LGBT adults at school, gay–straight alliance at school, online LGBT resources, LGBT presence in the community, accepting religious community, and LGBT family members) were discussed by participants. These resources were social and informational in nature. In each of these social contexts, youth reported both stressors and coping resources related to their sexual and gender minority status. Further, handling stress in one domain often involved coping via resources in different domain. Given this intersection, we present the following results by social context, with emphasis on the unique stress and coping resources participants described.

Family

Many participants reported expecting rejection by their families: “[My parents] already have the perception that ‘Here’s my good Chinese daughter.’ And I’m just kind of a little bit scared to deal with [the] repercussions of what happens when that perception of me changes with my disclosure” (cisfemale, Asian, lesbian, 16).

Because of this fear of rejection, some participants reported concealing their sexual identity to maintain the status quo in their family. In several cases, this meant lying to family members when asked about their sexuality. Youth also reported difficulty finding the words to disclose their sexual identity: “With my family, like I wanted them to know, but I didn’t know how to bring it up” (cisfemale, Latino, lesbian, 17). “If some person asked me, I’d sort of say, yeah. But if I have to tell them I’d freeze up and not know what to do” (cisfemale, White, lesbian, 17). Disclosure decision-making was a process that many youth encountered in their family. Several youth noted that disclosure to their family involved negative repercussions (e.g., violence, punishment, isolation from peers).

One youth reported how rejection from his mom following disclosure influenced his mental health:

[My mom] was like … “I’m so disappointed.” I’m like, “Why are you disappointed? Do you think I’m gay now?” She was like, “Well, what else am I supposed to think?” And I was like, “I don’t know,” so I was really quiet during seventh and eighth year. … I started cutting myself because that was the only way to feel something other than the numbness I felt inside. … [It] distracts me of my internal pain. (cisfemale, Latino, bisexual, 17)

Despite reports of stress in the family domain, youth also reported several coping resources. For example, although some youth expected rejection, others expected acceptance: “I’m going to assume [that my mom] is super cool like that. Her best friend since seventh grade is lesbian” (transmale, Latino, pansexual, 15). Additionally, when youth disclosed their identity, many were met with affirmation instead of discrimination.

So I came out to my dad … [and he said] “I knew since you were younger that you were lesbian.” And it felt like a huge relief that he accepted me … and he accepts me coming to the [LGBT] center … and he’s OK with me having girlfriends. And it was just awesome and it’s nice to be able to bring a girl home and be like, “Hey, this is my family,” and actually not be embarrassed or ashamed. (cisfemale, Latino, lesbian, 16)

Participants also described how having sexual minority family members and seeing them treated positively made them feel more conformable being a sexual minority in their family. One youth talked about seeing his family respond to his lesbian cousin:

My cousin is … a lesbian. I’ve never talked to her about me. But I’ve talked to her about her [and] she said coming out … her dad was like really old school but her dad understood. Yeah, she told me like a really nice story about her dad understood when she came out. It was happy times. … I’ve never heard [my parents] say anything bad. Because we all went to [my cousin’s] wedding. … They didn’t really say anything about them being girls. They were just like, “Oh, that was a nice wedding. They were so cute together.” (cismale, White, pansexual, 15)

School

After family, school was the context most discussed by participants. Youth reported experiencing several forms of discrimination in school (e.g., unsupportive teachers and administrators, seeing other LGBT peers treated badly at school). One participant reported how the principal of the school threatened to “out” him to his teachers. Verbal (e.g., called derogatory names, threatened with violence) and physical (being stabbed, pushed, hit) victimization were also discussed. One youth even reported an altercation with one of his teachers during which the teacher called him a “faggot” (cismale, Latino, pansexual, 19).

Youth discussed uncertainly about whom to trust at school. This included both peers and adults. Participants reported a fear of being rejected based on conversations they would hear in school: “Some don’t [know that I am LGBT] and they just talk about it and I’m just like … I’m not going to come out … [because of] the homophobic words that they use. They see like another queer person out there and they just make fun of them and say how disgusting it is” (cisfemale, Latino, bisexual, 18).

Coping resources at school were also discussed. The presence of a gay–straight alliance provided support for youth as they navigated safety, affirmation, and pride in their school: [The alliance] is a place that makes me happy because people don’t judge me. … I feel better surrounded by the people [like] us” (cismale, White, pansexual, 15). Youth also discussed the safety of having a supportive adult in school:

I had a history teacher that was the greatest teacher I ever had … and then I think she knew [about me being bisexual]. … I was talking to her and she said, “So, do you feel comfortable on campus?” and I was racking my brain like, “How does she know that I’m not straight?” And then I was like, she’s trying to have a conversation with me about if I feel safe. She’s worried about me. And so I was just like, “Yeah, I feel safe.” … I was like … she’s caring about me. (cisfemale, White, bisexual, 18)

Peers and social media

Outside of school, youth interacted with their peers and friends in person and via social media. Participants reported an expectation that they would be rejected by their peers:

I was really scared and afraid that if someone found out, everything would be bad. I didn’t know how [my friend] would act if he really found out who I was because I was getting close to this guy. … I mean, I didn’t like him or anything. It was just like I don’t want to lose a best friend. (cisfemale, Latino, lesbian, 17)

Once youth had been outed or disclosed their minority identity to their peers, they reported multiple forms of discrimination (e.g., loss of friendship, friends using derogatory language in jokes). Several youth reported a fear of victimization after disclosure: “I only told certain people [about being gay] and I was very afraid to tell other people because I could have been beat up or killed” (cismale, White, gay, 17).

I specifically remember we were in the middle of warm-ups and this kid goes, “All Black people, all gay people, and all Jews should die in a pit,” and I was just like what do I do with that? … He just said something so dehumanizing and like that he wants me to die multiple different ways. (cismale, Asian, gay, 19)

Youth reported experiences of being bullied via social media following disclosure: “Some [Facebook] comments that were very negative [said] ‘You need to kill yourself’” (cismale, African American, pansexual, 15).

Youth also discussed leveraging peer coping resources. Although, participants reported experiences of being victimized, they also reported social resources that made them feel safe:

I was on the bus one day and these kids were on the bus. … I was going to get off [because] they were making these [homophobic] remarks about me. … This girl, she was sitting all the way in the front of the bus. … She got up, left her stuff there, and was like, “I don’t like you guys making these remarks. You never know who can be gay. You never know if your friend right there is gay. What if he’s gay and he’s just pretending to be straight in front of you guys? You never know who can be gay.” She just kept on defending and defending me and it made me feel so special knowing there are people who will stand up for someone they don’t know. (cismale, Latino, gay, 16)

Multiple youth reported affirmation from their friends and peers once they disclosed their sexual identity. In an effort to connect with other sexual minority peers, youth also reported using online resources and social media sites to leverage relationships and build pride in their sexual minority identity.

Religion

Although not all youth reported maturing in a religious community or family in which religion had high importance, for those in contexts in which religion was salient, minority stress played a meaningful role. Multiple youth reported expectations and experiences of rejection, including being told “You’re going to hell” and being described as an “abomination.” Additionally, when youth disclosed their identity, they experienced discrimination and in several cases, religious authorities who tried to change their sexual identity: “One of the pastors that knew about [me] took me in and tried to change me straight and stuff like that and teach me how to be a man” (cismale, African American, gay, 17).

Due to the negative religious messages about sexual minorities, youth also reported internalizing stigma related to their sexual identity: “Before I thought that I was … a mistake, like I’m wrong, and that I was just like something that just like, should change” (cismale, Latino, gay, 14). “I hated myself because they were telling me [being gay was a sin]. … It made me feel like I didn’t want to become that person. That’s when I started thinking I wanted to be straight” (cismale, Latino, bisexual, 15).

Although religion was a source of stress for many youth, several participants reported coping resources in this context. Some respondents reported maturing in religious communities that were affirming to sexual minority people: “I identify as Jewish. … They do accept gays and the most beautiful thing is that it’s a religion about people” (cisfemale, Latino, lesbian, 16).

Several youth also reported how religious beliefs helped build pride and confidence in themselves and their sexual identity. One youth in particular discussed this effect of religion on his process of acceptance:

I’ve got a few principles stuck in my brain and it said do no harm to others but do your will … just don’t harm anyone. Don’t hurt anyone physically, emotionally, mentally, spiritually … and just be yourself. That made me believe in my whole being, my sexuality, my mental ability, my strength, my hope. (cismale, Asian, gay, 16)

Racial and ethnic community

Racial and ethnic community was an especially relevant domain for racial and ethnic minority participants. Asian, African American, and Latino participants reported a general fear of rejection by their racial and ethnic community. Youth who feared rejection also discussed experiences of discrimination:

I’ll get dirty looks [from other Latino people] for the way I stand, for the way I talk, for the way my hand gestures … just everything I do, I’ll get dirty looks and they’re like, “Oh, there’s the maricón [faggot].” (cismale, Latino, gay, 16)

Several youth reported how these experiences of discrimination influenced their internalized stigma about being a sexual minority.

Participants discussed ways of coping with minority stress from their racial and ethnic group. For example, one coping resource that provided affirmation and a sense of pride was seeing other LGBT individuals of diverse racial and ethnic groups. Youth who identified as mixed race also reported coping by overidentification with one ethnic community, particularly one that seemed more affirming of sexual minorities. For example, one participant who was both African American and Native American coped with discrimination in the African American community by identifying more as Native American.

LGBT community

Although the LGBT community is a place for coping, youth reported experiences of minority stress in the LGBT community. Several youth discussed how their local LGBT community made them feel like outsiders for not being gay: “It can be a little difficult because I don’t fit in … with the gays. … I’m not part of that scene because I’m pansexual. … There is stigma against bisexuals and anything other than gay or straight, now” (cismale, Latino, pansexual, 19). This was especially true for youth of color:

I guess I could say in the LGBT community, if you’re White, it seems like you have more of a say-so. It seems like, to me anyways, in terms of your voice is a bit more heard. If you’re a person of color in the LGBT community, you’re not as heard.” (cismale, White, pansexual, 17)

One participant reported discrimination based on his race in the LGBT community:

I felt like fetishized because of my race. Like, he’s like, “Oh, I’ve never been with a Pacific Islander before. I like Mexicans and I like Latins.” I’m scared that sometimes White people, in terms of sexual relations, like I sometimes feel like they’re going to fetishize me. (cismale, Asian gay, 19)

Youth reported multiple coping resources in the LGBT community. Besides supportive adults and other LGBT peers, youth discussed the importance of leveraging services at LGBT community centers and the opportunity to be involved in LGBT activities. Involvement in community activities built pride for youth: “Well, I’m just proud … of being gay, yeah like … I’ll tell people straight out, participate in gay activities and I’ll wear the rainbow bracelets and all that stuff” (cisfemale, Latino, bisexual, 18).

Importance of considering multiple social contexts

For many participants, minority stress experiences occurred in one context but not all. In the present study, many participants reported experiencing stress in one context and managing that stress by relying on resources in another context. For example, several youth discussed how their parents were supportive when they were bullied for being a sexual minority:

[At school] they’d be like “faggot” and stuff like that. It hurt me. It hurt me a lot but my parents pretty much told me not to worry about them and that I’m better than those people because I don’t judge other people. (cismale, Latino, bisexual, 17)

One youth reported how he leveraged his cousin (i.e., family coping resource) to gain a resource in the LGBT community context:

My cousin, who was also gay, he moved out of the household because he was dealing with the same [family acceptance issues]. And he got away, and called me and said, “Hey, there is this youth group that you should go to” that was local where I lived. He was like, “I really want you to check it out. I feel like you need the support.” And I went. (cisfemale, Latino, lesbian, 16)

Although multiple youth discussed how the LGBT community context provided needed support, several youth reported how underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minority youth made coping with coming out more difficult:

[The LGBT community is] all White. … It’s just like … I know one of my best friends is a Black gay, so we can like relate … we can talk about stuff. Like, you know, we went through the same thing. … It’s like a cultural difference, I guess. It’d be like a cross-cultural setting between Caucasians and Blacks. It’s easier for a White person to come out because usually their parents are more open. … Imagine being a trans Black person. (cismale, African American, gay, 19)

Most youth who were interviewed reported compulsory social contexts (e.g., school, family, religion). Because in many situations youth were unable to escape minority stress, relying on coping resources from a different social context became necessary. Therefore, participants highlighted the importance of the social context in understanding both experiences of minority stress and the salience of their sexual identity.

Sexual identity development

Somewhat consistent with the minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003), sexual identity was discussed regularly throughout the interviews. However, these youth focused primarily on the emergence and development of sexual identity through adolescence and the stress of this process, as opposed to the presence of identity stress conveyed by Meyer (2003). Many participants (40%) reported an initial feeling of difference from their peers but unawareness of the details of that difference until they had a realization about their sexual identity. Sexual identity development for participants was dynamic, with 44% of participants reporting that they changed their sexual identity labels at least once:

I’ve just been happy with [how I identify]. But [then] after figuring things out, I realized that I’m not bisexual, I’m pansexual. … I’d started realizing that it’s not just, “Oh, I like girls and guys.” I also like trans and others and whatnot. (cisfemale, Latino, pansexual, 16)

Participants discussed how this label change was often due to learning new information about sexuality.

In different social contexts, youth reported how observing heterosexual expectations from family and peers complicated their process of processing their sexual identity. One participant who identified as lesbian recounted:

Even my guy friends would date girls. They would never date another guy. My friends that were girls, they never dated other girls. So, to me, that was like, OK, that’s what I have to do. … I kept thinking that one day I’d be attracted to a guy and I’d fall in love with a guy and I’d marry a guy and I’d have a child with a guy. That’s what I kept thinking. (cisfemale, Latino, lesbian, 17)

Processing one’s identity was a stressful experience. Although some youth reported recognizing their sexual identity was a relief from the feeling of being different, many youth also reported significant stress from this realization.

Discussion

Our study provided support for a minority stress-informed understanding of sexual minority adolescents. In addition, our study revealed three key themes for understanding the adolescent-specific minority stress experience: (a) youth experience minority stress and also readily identify key coping resources; (b) social context is an important factor in understanding both stress experiences and coping resources available to youth not previously described by the minority stress theory; and (c) sexual and gender identity developmental processes are an important element of minority stress that should be considered in a manner more developmentally appropriate for this age group.

Building on the original theory, Figure 2 illustrates our conceptual understanding of these key areas of interest. Our proposed deviations from the basic structure of the minority stress theory are indicated in bold. The circles represent each social context and smaller gray boxes in each social context represent general stressors, distal minority stress, and proximal minority stress.

Figure 2.

Proposed Minority Stress Model

1: Peer and Social Media; 2: Racial/Ethnic Community; 3: LGBTQ Community

Coping processes in adolescents

Sexual minority adolescents in our study found ways to cope, perhaps because “coping is a major factor in the relation between stressful events and adaptational outcomes such as depression, psychological symptoms and somatic illness” (Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel-Schetter, DeLongis, & Gruen, 1986, p. 992). As Lazarus and Folkman (1984) described, coping is generally a direct response to stress that is appraised as taxing or exceeding an individual’s resources and is process oriented and contextual. Given the intrinsic relationship between stress and coping, we were not particularly surprised to find that youth regularly reported the presence of coping in the face of adversity.

The minority stress theory describes in some detail the relationship between stress and “stress-ameliorating factors” (Meyer, 2003, p. 6) and highlights that the relationship between stress and coping with minority experiences is complicated. For example, concealment of sexual identity may be both a stress and a coping process. Some research has indicated that coming out builds resilience and allows sexual minorities to cope with the adverse effects of stress (Morris, Waldo, & Rothblum, 2001). However, identity disclosure may come with real (e.g., violence, rejection) and expected consequences (D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001; Goldbach et al., 2014). On the other hand, concealing a minority identity can also have stressful consequences because it adds cognitive burden and preoccupation (Miller & Major, 2000; Smart & Wegner 2000).

In the present study, many of these coping skills did present in interviews with youth. However, many participants also described supportive parents, teachers, and the presence of a gay-straight alliance (GSA) or LGBT center as meaningful coping resources that existed in their lives and helped to cope with minority stress. Thus, in our proposed adaptation to the minority stress model we suggest that coping resources be assessed directly, and in more depth. This has several scientific and clinical implications.

First, more research is needed to better integrate coping resources as they relate to minority stress domains. In the sparse literature on coping among sexual minority adolescents, factors such as explicit family support and perceived acceptance have been associated with better outcomes for this population (e.g., Padilla, Crisp, & Rew, 2010). But, how one can measure perceived acceptance is unclear. Recently, studies have examined social structures that may influence perceived acceptance in sexual minority adolescents and serve as coping resources. For example, in a study of state-level policies and psychiatric morbidity among LGB adults (Hatzenbuehler, Keyes & Hasin, 2009), adults living in states with hate crime and employment discrimination protections were less likely to report generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and dysthymia than those in states without such policies. Among youth, Hatzenbuehler (2011) found that youth who lived in more supportive counties (as measured by the proportion of same-sex couples, registered democrats, GSA’s in schools and protective school policies) were 20% less likely to attempt suicide than sexual minority adolescents who lived in less supportive environments. Thus, whereas the original minority stress theory indicates expectations of rejection as a key stress domain, better assessment of expectations of acceptance based on the presence of perceived coping resources (for example) may allow for a more complex understanding of behavioral health moving forward. Subsequently, while some stressors such as those in the family and with peers cannot be easily attenuated, many of these coping resources can be put in place through school, county, and statewide policy change.

Social context

Perhaps the most significant finding of the present study is the clear importance of how social context affects both stress and coping among sexual minority adolescents. Although youth often reported finding significant stress in one area of their life, they also reported coping resources in another. Few scholars dispute the relationship between social environment and individual well-being. Research dating back more than a century (e.g., Durkheim, 1897/1951) has established a link between the social contexts in which we live and work and behavioral health patterns including suicide risk (Durkheim, 1897/1951), mental health concerns, and substance abuse (Heaney & Israel, 2002; Wenzel, Glanz, & Lerman, 2002). Research on this relationship has commonly been rooted in social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), which suggests that human behavior can be understood through an individual’s interaction with the social environment. Although traditional developmental theories generally center on the individual’s identity as related to society (Minton & McDonald, 1984), social identity theory focuses on the contexts in which we live and how they influence behavior. Based on the theory’s assumptions, interpretations can be made about the individual’s behaviors and self-perceptions by examining interactions (whether stressful or positive) in various social contexts.

In the minority stress theory, these experiences may be categorized as “circumstances in the environment” (Meyer, 2003, p. 8). However, the variety of contexts in which sexual minority adolescents interact each day may represent discriminant places for stress and coping. For example, peer-perpetrated victimization and discrimination occur at higher rates among sexual minority adolescents youth than heterosexual youth (D’Augelli, Hershberger, & Pilkington, 1998; Russell et al., 2001), and LGBT youth often report losing friends and social support after disclosing their sexual identity (Pilkington & D’Augelli, 1995). On the other hand, Wright and Perry (2006) found that youth who disclosed their sexual identity to more people and felt supported were less likely to have distress associated with mental health and substance use problems. Supportive family members have been associated with positive outcomes for sexual minority adolescents (Ryan et al., 2012), yet growing up in families that are highly religious has been implicated in risk of suicide (Gibbs & Goldbach, 2015).

Given our findings that affirm the complex nature of interacting social contexts for sexual minority adolescents, we propose that the model should consider each component of the minority stress model (i.e., coping skills and resources, general stressors, distal and proximal minority stressors) within the context of each key social environment. For adolescents, these seem to be the family, school, peers, religious communities, racial and ethnic community, and the connection to the LGBTQ community. Although more complex to consider in research design and analysis, it is plausible that a minority stress and coping model could be created six times over for every individual domain. Further, analysis could focus more comprehensively on both a single domain as well as the interactions across multiple domains to better understand how these stress experiences lead to differential outcomes. We contend that without accounting for the potentially vast differences across these social domains, however, our understanding of behavioral health in this population will continue to be limited.

Developmental stressors

A final adaptation we propose for considering minority stress within the context of adolescence is related to sexual identity development. Participants in this study described their process of realizing their sexual minority identity and finding an identity label that fit their experience. This process was stressful for some and in many cases depended on the social context in which they observed heterosexual norms. Both sensitization and acceptance of sexual minority status are aspects of sexual minority identity-stage models (e.g., Cass, 1979; Coleman, 1982; Troiden, 1979), but not necessarily aspects of the original theory (Meyer, 2003), which is not specified to developmental changes.

The minority stress theory does account for the prominence, valence and integration of the minority identity as it may interrupt the stress and health relationship. That is, as we described previously, the relative importance of a minority stress on behavioral health outcomes is influenced by how “important” the individual believes that identity to be. However, for adolescents, identity formation is a central developmental task (Erikson, 1968), and the processes of sexual minority identity sensitization and identity acceptance can be stressful. These issues are typically resolved when it comes to sexual minority adults, who likely have a more formulated identity concept. This is not to say that adults do not have unresolved issues related to their sexual identity, just that they have generally resolved at the very least their identity label. Yet, due to developmental stage, sexual and gender identity processes may act as additional minority stressors during adolescence, which have not been articulated as extensively in the original model (Meyer, 2003).

Thus, we propose in our adapted minority stress model for adolescents that within the characteristics of minority identity, “development” should be closely considered. Future research should include a more refined investigation of contemporary identity labels (e.g., pansexual, queer, asexual) and their meaning for adolescents who ascribe to them, as these “post gay” labels have only been recently considered in research with this population (for exception, see Russell, Clarke & Clary, 2009; Lapointe, 2016). These findings also have potential importance for clinical settings, where youth may present with a variety of sexual identity labels that go outside of lesbian, gay and bisexual. Given the significance of identity development during this life stage, its relation to behavioral health, and the lack of existing knowledge of how important these alternative labels may be to young people, it appears that care should be taken in ensuring identity affirming approaches are used (e.g., Craig, Austin & Alessi, 2013; Alessi, 2014

Limitations and conclusions

Our study is not without limitations. Although we purposefully recruited diverse youth in terms of racial and ethnic background, gender, and sexual orientation, this also meant we had small subsamples. Relatedly, although all participants identified as a sexual minority. Some also identified as genderqueer or transgender; due to the small number of participants, we cautiously assert these findings may also be applicable to gender-nonconforming youth, but additional research must be done to identify which specific minority stress and coping processes are convergent and where these two groups may differ. More work is also needed to better elucidate the nuanced relationships among race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, and coping. Finally, the present sample was recruited from a large urban area. It is possible that youth who mature in rural areas may experience different stressors related to being a sexual minority and employ different forms of coping.

Despite these limitations, we assert that the initial concerns guiding our study are worthy of further attention. Despite commonly being grouped in the category of youth, spanning a wide range of ages from 12 to 25 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016), adolescents are not the same as their young adult counterparts. Beyond biopsychosocial developmental processes occurring during adolescence, sexual minority adolescents are growing up in a world that is far different than it was in 2003. With advances in human rights protections (e.g., repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell; marriage equality), identifying as a sexual minority is not considered universally negative and there is an important value in exploring both the coping resources that counteract stress experiences and the various contexts in which youth report stress and coping, with special attention to developmental processes. Understanding how sexual minority adolescents experience stress and rely on coping resources in the context of diverse environments will meaningfully contribute to the prevention of behavioral health disorders in this population of high need.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no actual or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence, or be perceived to influence, their work.

References

- Alessi EJ. A framework for incorporating minority stress theory into treatment with sexual minority clients. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 2014;18(1):47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Alessi EJ, Martin JI, Gyamerah A, Meyer IH. Prejudice events and traumatic stress among heterosexuals and lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2013;22:510–526. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2013.785455. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anhalt K, Morris TL. Developmental and adjustment issues of gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: A review of the empirical literature. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:215–230. doi: 10.1023/a:1022660101392. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1022660101392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Nelson LA, Birkett MA, Calzo JP, Everett B. Eating disorder symptoms and obesity at the intersections of gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation in US high school students. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:e16–e22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301150. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer DM. A brief, selective history of the Department of Human Development and Family Life at the University of Kansas: The early years. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:569–572. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-569. http://dx.doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1993.26-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Thornton A, Freedman D, Amell JW, Harrington H, Silva PA. The life history calendar: A research and clinical assessment method for collecting retrospective event-history data. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1996;6:101–114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1234-988X(199607)6:2<101::AID-MPR156>3.3.CO;2-E. [Google Scholar]

- Cass VC. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality. 1979;4:219–235. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among youth: Fast facts. 2016 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/youth/

- Chanmugam A. Perspectives on US domestic violence emergency shelters: What do young adolescent residents and their mothers say? Child Care in Practice. 2011;17:393–415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2011.596814. [Google Scholar]

- Chesir-Teran D, Hughes D. Heterosexism in high school and victimization among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:963–975. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9364-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9364-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatts MC, Goldsamt L, Yi H, Gwadz MV. Homelessness and drug abuse among young men who have sex with men in New York City: A preliminary epidemiological trajectory. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.02.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E. Developmental stages of the coming out process. Journal of Homosexuality. 1982;7(2–3):31–43. doi: 10.1300/j082v07n02_06. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J082v07n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:393–403. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.101.3.393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:87–127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Stoll MF, Thomsen AH, Oppedisano G, Epping-Jordan JE, Krag DN. Adjustment to breast cancer: Age-related differences in coping and emotional distress. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 1999;54:195–203. doi: 10.1023/a:1006164928474. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1006164928474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig SL, Austin A, Alessi E. Gay affirmative cognitive behavioral therapy for sexual minority youth: Clinical adaptations and approaches. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2013;41:258–266. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR. Coming out, visibility, and creating change: Empowering lesbian, gay, and bisexual people in a rural university community. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;37:365–376. doi: 10.1007/s10464-006-9043-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10464-006-9043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH. Disclosure of sexual orientation, victimization, and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:1008–1027. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/088626001016010003. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:361–371. doi: 10.1037/h0080345. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0080345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Pilkington NW, Hershberger SL. Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths in high school. School Psychology Quarterly. 2002;17(2):148. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM. Development of sexual orientation among adolescent and young adult women. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1085–1095. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.1085. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.34.5.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. Suicide: A study in sociology. New York, NY: Free Press; 1897/1951. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Beautrais AL. Is sexual orientation related to mental health problems and suicidality in young people? Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:876–880. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.876. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CM. Assessing developmental trajectories of sexual minority youth: Discrepant findings from a life history calendar and a self-administered survey. Journal of LGBT Youth. 2012;9:114–135. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2012.649643. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2012.649643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CM, Boudreau ME. Assessing recent adolescent sexual risk using a sexual health history calendar: Results from a mixed method feasibility study. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2014;25:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.06.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLougis A, Gruen RJ. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:992–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.5.992. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, Wei C, Wong CF, Saewyc EM, Stall R. A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101:1481–1494. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190009. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.190009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup. Marriage. 2016 retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/117328/marriage.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network. 2011 National School Climate Survey. 2012 Retrieved from http://glsen.org/press/2011-national-school-climate-survey. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs JJ, Goldbach J. Religious conflict, sexual identity, and suicidal behaviors among LGBT young adults. Archives of Suicide Research. 2015;19:472–488. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2015.1004476. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2015.1004476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs JJ, Rice E. The social context of depression symptomology in sexual minority male youth: Determinants of depression in a sample of Grindr users. Journal of Homosexuality. 2016;63:278–299. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2015.1083773. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2015.1083773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, Gibbs J. Stress, coping and multiple minority status: The intersection of racial/ethnic and sexual minority status during adolescence; Oral presentation at the Society for Prevention Research Annual Conference; Washington, DC. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, Schrager SM, Dunlap SL, Holloway IW. The application of minority stress theory to marijuana use among sexual minority adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse. 2015;50:366–375. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.980958. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2014.980958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, Tanner-Smith EE, Bagwell M, Dunlap S. Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: A meta-analysis. Prevention Science. 2014;15:350–363. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0393-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0393-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, Mathy RM, Cochran SD, D’Augelli AR, Clayton PJ. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: Review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality. 2010;58:10–51. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.534038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold RD, Palmiter ML, Lynch SA, Freedman-Doan CR. Life stories: A practice-based research technique. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare. 1995;22:23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011;127:896–903. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:2275–2228. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science. 2009;20:1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney C, Israel B. Social networks and social support. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research and practice. 3rd. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 185–209. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the minority stress model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2012;43:460–467. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0029597. [Google Scholar]

- Herts KL, McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking stress exposure to adolescent aggressive behavior. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2012;40(7):1111–1122. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9629-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J. A state-by-state examination of nondiscrimination laws and policies: State nondiscrimination policies fill the void but federal protections are still needed. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress Action Fund; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher C. Minority stress and health: Implications for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2009;22:373–379. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09515070903334995. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Bartkiewicz MJ, Boesen MJ, Palmer NA. The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York, NY: Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Palmer NA, Kull RM. Reflecting resiliency: Openness about sexual orientation and/or gender identity and its relationship to well-being and educational outcomes for LGBT students. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2015;55:167–178. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9642-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe A. Postgay. In: Brockenbrough E, Ingrey J, Martino W, Rodriguez NM, editors. Critical concepts in queer studies and education: An international guide for the twenty-first century. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillian; 2016. pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, Brent DA. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49(2):115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, Thompson AL. Individual trajectories of substance use in lesbian, gay and bisexual youth and heterosexual youth. Addiction. 2009;104(6):974–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Major B. Coping with prejudice and stigma. In: Heatherton T, Kleck R, Hull JG, editors. The social psychology of stigma. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 243–272. [Google Scholar]

- Minton HL, McDonald GJ. Homosexual identity formation as a developmental process. Journal of Homosexuality. 1984;9:91–104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J082v09n02_06. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock SE, Eibach RP. Aging attitudes moderate the effect of subjective age on psychological well-being: evidence from a 10-year longitudinal study. Psychology and aging. 2011;26(4):979. doi: 10.1037/a0023877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JF, Waldo CR, Rothblum ED. A model of predictors and outcomes of outness among lesbian and bisexual women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71:61–71. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.1.61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.71.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Kuper L, Greene GJ. Development of sexual orientation and identity. In: Tolman DL, Diamond LM, editors. Handbook of sexuality and psychology. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 597–628. [Google Scholar]

- Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Padilla YC, Crisp C, Rew DL. Parental acceptance and illegal drug use among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: Results from a national survey. Social Work. 2010;55:265–275. doi: 10.1093/sw/55.3.265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/sw/55.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 3rd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington NW, D’Augelli AR. Victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings. Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:34–56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(199501)23:1<34::AID-JCOP2290230105>3.0.CO;2-N. [Google Scholar]