Abstract

Objective

To evaluate feasibility, efficacy and tolerability of Sudarshan Kriya yoga (SKY) as an adjunctive intervention in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) with inadequate response to antidepressant treatment.

Method

Patients with MDD (defined by DSM-IV-TR) depressed despite ≥8 weeks of antidepressant treatment were randomized to SKY or a waitlist control (delayed yoga) arm for 8 weeks. The primary efficacy end point was change in 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17) total score from baseline to 2 months. The key secondary efficacy end points were change in Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) total scores. Analyses of the intent-to-treat (ITT) and completer sample were performed. The study was conducted at the University of Pennsylvania between October 2014 and December 2015.

Results

In the ITT sample (n=25), the SKY arm (n=13) showed a greater improvement in HDRS-17 total score compared to waitlist control (n=12)(−9.77 vs. 0.50, P =.0032). SKY also showed greater reduction in BDI total score versus waitlist control (−17.23 vs. −1.75, P = .0101). Mean changes in Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) total score from baseline were significantly greater for SKY than waitlist (ITT mean difference: −5.19; 95% CI −0.93 to −9.34; P = .0097; completer mean difference: −6.23; 95% CI −1.39 to −11.07; P = .0005). No adverse events were reported.

Conclusion

Results of this randomized, waitlist-controlled pilot study suggest the feasibility and promise of an adjunctive SKY-based intervention for patients with MDD who have not responded to antidepressants.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02616549

Keywords: clinical trial, major depressive disorder, Sudarshan Kriya yoga, SKY

INTRODUCTION

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) has been recognized as a major public health issue. In 2014, an estimated 15.7 million or 6.7% of adults in the United States had at least one major depressive episode in the past year.1 As a leading cause of disability among mental disorders, MDD results in significant functional impairment and increases the risk of medical co-morbidity and mortality.2 Furthermore, the loss in productivity has considerable economic ramifications,3 especially among patients who do not respond to treatment.4,5

Antidepressant medications and psychotherapy offer effective first line treatments for MDD, but only about 50–60% of patients respond to the initial course of therapy.6 Moreover, among those patients who improve with treatment, the subset who do not achieve clinical remission are at markedly increased risk for relapse.7 While a number of adjuncts are used to enhance the effects of antidepressant treatments, they typically offer limited additional benefits.8 Side effects can also limit their use, prolonging the duration of a major depressive episode. Consequently, effective adjunctive treatments with favorable tolerability are needed for those who do not fully respond to antidepressant monotherapy.

Yoga interventions include a diverse group of movement and meditative practices that are increasingly being evaluated in the treatment of mental disorders.9 Sudarshan Kriya yoga (SKY) is a breathing-based meditation technique previously proposed to improve symptoms of depression.10,11 In initial research, SKY has demonstrated an antidepressant response in patients with dysthymic disorder,12 depression due to alcohol dependence13 and for inpatients with MDD.14 In these clinical samples, the intervention was well-tolerated. Furthermore, SKY has been reported to decrease cortisol, increase prolactin and improve antioxidant status in practitioners.12,15 Consequently, SKY has therapeutic potential as an antidepressant intervention and as an adjunctive treatment for MDD.

Despite increased interest in yoga interventions16, well-designed clinical studies that evaluate these approaches are needed, especially in the context of standard outpatient care for MDD. The objective of this randomized pilot study was to evaluate the feasibility, efficacy and tolerability of a SKY-based intervention in MDD outpatients with inadequate response to antidepressants.

METHOD

Patients

Adult outpatients aged 18–67 years were enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania Mood and Anxiety Disorders Treatment and Research Program (MADTRP). Written informed consent was obtained for study procedures approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board and the study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT02616549). Patients were diagnosed with a single or recurrent nonpsychotic episode of MDD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria.17 During the current episode, patients needed be on a stable (≥ 8 weeks) dose of an antidepressant(s), which they were required to continue (without dose changes) for the additional 8 week study period. Eligible patients had 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17)18 total scores ≥ 14 at screening and baseline visits. Exclusion criteria included bipolar disorder, psychosis, substance abuse, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, pregnancy, epilepsy or initiating psychotherapy and/or other yoga and meditation programs.

Study Design

This randomized, rater-blind, waitlist-controlled study was conducted between October 2014 and December 2015. A blocked randomization procedure (“blockrand” package from the R statistical programming software19) was utilized to create randomized blocks with age and sex as the blocking factors. Within each possible block, study subjects were randomly assigned with equal probability to either the SKY or waitlist group. Subjects assigned to the waitlist arm were offered the yoga intervention after completing the study.

The yoga intervention consisted of two phases of a manual-based, group program featuring a breathing-based meditative technique called Sudarshan Kriya yoga (SKY). SKY includes a series of sequential, rhythm-specific breathing exercises that bring practitioners into a restful, meditative state. The breathing exercises have been previously described in detail10. During the first phase (Week 1), participants completed a six-session SKY program, which featured SKY in addition to yoga postures, sitting meditation and stress education (3.5 hours per day; Supplementary eTable 1). During the second phase (Week 2–8), participants attended weekly SKY follow up sessions (1.5 hours per session) and were asked to complete a home practice version of SKY (20–25 minutes per day; Supplementary eTable 2). Compliance with the follow-ups and home practice were recorded in participant log sheets. Certified SKY instructors were from the Art of Living Foundation and the International Association of Human Values. All sessions were conducted within the University of Pennsylvania Presbyterian Hospital Clinical and Translational Research Center (CTRC).

Outcome Measures

MADTRP blinded clinical raters conducted study assessments at three time points including baseline (≤ 1 week prior to yoga program), 1 month and 2 month visits. The primary efficacy variable was HDRS-17 total score. Secondary efficacy variables included the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) 20 and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) 21 total scores. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale 22 was used to evaluate suicidal ideation and behavior. Assessment of medication compliance and treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was conducted at each study visit.

Data Analysis

Data reported here are for both the intent-to-treat (ITT) or randomized sample and the completer sample. The ITT analysis was conducted using last observation carried forward (LOCF). The completer analysis comprised all patients who had an evaluation for HDRS-17 total score at baseline and ≥ 1 evaluation after the baseline visit. The primary efficacy endpoint was change in HDRS-17 score from baseline to 2 months. After verifying a normal distribution in the data (“car” 23 and “MASS” 24 package from R), the primary analysis was conducted by fitting a mixed effects linear model with an autoregressive variance covariance structure (“nlme” R package25). The model included one between-subjects factor (group), one within-subjects factor (time) and their interaction (group-by-time) as fixed effects terms. Subject was included as the random effects term. The same mixed effects model was applied for evaluation of key secondary efficacy measures (BDI and BAI). Multiple comparisons were evaluated using Tukey’s test (“multcomp” R package26) to adjust for multiplicity and maintain type I error at 0.05 (2-tailed).

RESULTS

Patients

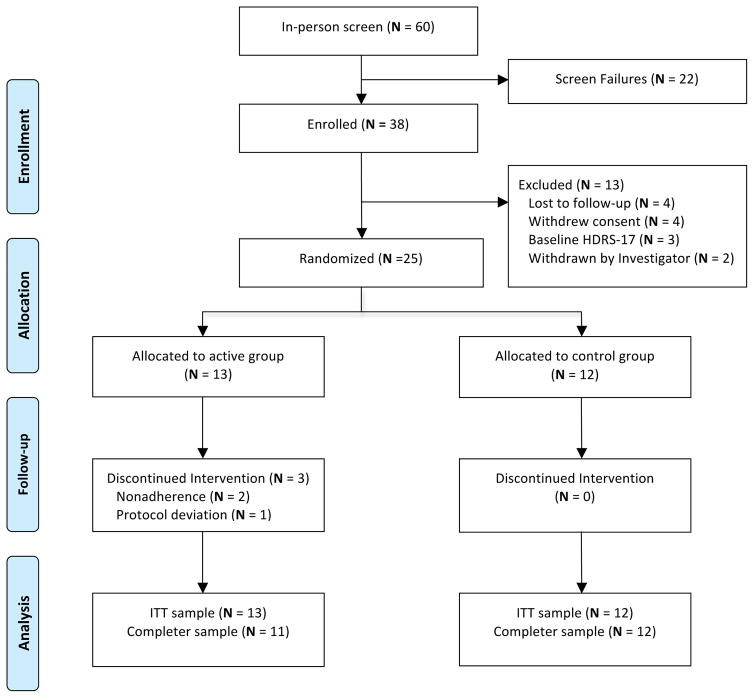

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of the randomized sample were similar between groups (Table 1). At the baseline visit, the mean HDRS-17 total score was 20.4, indicating severe depression. Of the sixty subjects initially screened, twenty-five (ITT sample) were randomized to the SKY active (n=13) or waitlist control (n=12) arms (Figure 1. Study Design and Patient Disposition). Two patients from the SKY arm left the study during Week 1, due to events unrelated to the study protocol. One patient in the SKY group left during Week 7, due to a protocol deviation involving a change in outpatient medication. Consequently, the completer sample consisted of 23 patients (SKY, n=11; waitlist, n=12). Of the randomized patients, 10/13 (77%) of SKY and 12/12 (100%) waitlist control patients completed the entire treatment phase. There were no reported TEAEs for either group.

Table 1.

Demographic and Baseline Clinical Characteristics (ITT sample)

| Variable | SKY (N =13) | Control (N=12) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Agea, mean (SD), y | 39.4 (13.9) | 34.8 (13.6) |

| Female sexa, n (%) | 9 (69.2) | 9 (75) |

| Racea, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 12 (92.3) | 11 (91.7) |

| African American | 1 (7.7) | 1 (8.3) |

| Educationa, n (%) | ||

| High School Degree | 1 (7.7) | 3 (25) |

| College Degree | 8 (61.5) | 6 (50) |

| Graduate Degree | 4 (30.8) | 3 (25) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Duration of current episodea, mo, n (%) | ||

| 0 – 6 | 3 (23.0) | 6 (50) |

| 6–12 | 5 (38.5) | 4 (33) |

| >12 | 5 (38.5) | 2 (17) |

| No. of lifetime episodesa, mean (SD) | 5.6 (3.1) | 5.3 (2.5) |

| No. of prior antidepressantsa, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 3 (23.0) | 3 (25) |

| 3 | 4 (30.8) | 2 (16.7) |

| 4+ | 5 (38.5) | 7 (58.3) |

| HDRS-17 total score, mean (SD)a | 22.0 (3.8) | 18.6 (3.7) |

| BDI total score, mean (SD)a | 32.7 (6.7) | 26.6 (7.9) |

| BAI total score, mean (SD)a | 13.8 (7.4) | 16.9 (9.4) |

Measured at baseline visit. P values (between groups) not significant.

Abbreviations: SKY= Sudarshan Kriya Yoga, ITT = intent-to-treat, HDRS-17 = 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory

Figure 1. Study Design and Patient Disposition.

Abbreviations: HDRS-17 = 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, ITT= intent-to-treat.

Outcomes

Primary Outcome

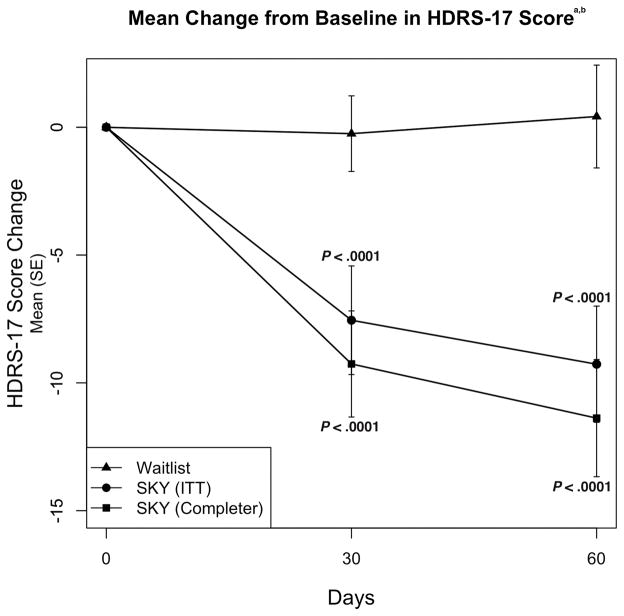

In the ITT sample, mean reduction from baseline to 2 months in HDRS-17 total score for SKY (−9.77) showed greater improvement compared to the waitlist control (0.50; mean difference = −10.27; 95% CI −5.04 to −15.50; P =.0032) (Figure 2). Mean change in HDRS-17 total score for the completer sample for SKY was −11.55 versus 0.50 for waitlist control (mean difference: −12.05; 95% CI −6.71 to −17.38; P =.0014) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mean Change from Baseline in HDRS-17 Score.

aBaseline HDRS-17 total scores were 22.0 for SKY (n=13, ITT sample) and 18.6 for waitlist control (n=12) groups.

bP values are based on mixed model repeated-measures analysis.

Abbreviations: HDRS-17 = 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, ITT= intent-to-treat, SE=standard error.

Secondary Outcomes

For the ITT and completer samples, SKY showed greater improvement compared to the waitlist control for the secondary efficacy measures (Table 2). Mean reductions in BDI total score from baseline to 2 months were greater for SKY (ITT: −17.23; completer: −20.36) compared to the waitlist control (−1.75; ITT mean difference: −15.48; 95% CI −8.34 to −22.62; P = .0101; completer mean difference: −18.61; 95% CI −11.81 to −25.42; P = .0043) (Table 2). Mean change in BAI total score from baseline to 2 months was greater for SKY (ITT: −5.44; completer: −6.48) versus for waitlist control (−0.25; ITT mean difference: −5.19; 95% CI −0.93 to −9.34; P = .0097; completer mean difference: −6.23; 95% CI −1.39 to −11.07; P = .0005) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Secondary Efficacy End Points: Mean Change in Outcome from Baseline to 2 months

| Outcome | Waitlist (n=12)

|

SKY (ITT sample, n = 13)

|

SKY (Completer sample, n=11)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change From Baseline | Change From Baseline | Difference From Waitlist Control in Change from Baseline

|

Change From Baseline | Difference From Waitlist Control in Change from Baseline

|

|||

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (95% CI) | P Value | Mean (SE) | Mean (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Scale | |||||||

| BDI, total score | −1.75 (2.56) | −17.23 (2.70) | 15.48 (−8.34 to −22.62) | 0.0101 | −20.36 (2.76) | 18.61 (−11.81 to −25.42 | 0.0043 |

| BAI, total score | −.25 (1.48) | −5.44 (1.60) | −5.19 (−0.93 to −9.34) | 0.0097 | −6.48(1.75) | −6.23 (−1.39 to −11.07) | 0.0005 |

| HDRS-17, total score | .50 (1.87) | −9.77 (1.90) | 10.27 (−5.04 to −15.50) | 0.0032 | −11.55 (2.00) | 12.05 (−6.71 to −17.38) | 0.0014 |

| HDRS responders (%)a | 8.33% | 46.15% | 0.0730 | 54.54% | 0.0271 | ||

| HDRS remitters (%)b | 8.33% | 30.77% | 0.3217 | 36.36% | 0.1550 | ||

Defined as patients having > 50% reduction from baseline HDRS-17 total score.

Defined as patients with HDRS-17 total score ≤ 7 and > 50% reduction in HDRS-17 total score from baseline.

Abbreviations: SKY = Sudarshan Kriya Yoga, ITT= intent-to-treat, HDRS-17 = 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory

DISCUSSION

In this waitlist controlled pilot study of patients with inadequate response to standard antidepressants, those who received an adjunctive intervention of Sudarshan Kriya yoga obtained significant improvement in depressive and anxious symptoms compared to the waitlist control. Beyond symptom relief, the intervention had a high completion rate without adverse events. To our knowledge, this is the first clinical study demonstrating SKY efficacy and tolerability as an adjunctive treatment for MDD outpatients with inadequate responses to antidepressants. In addition, this study assesses the response to administration of an adjunctive SKY treatment in comparison to the continuation of the subjects’ current medication regimen.

A prior study evaluating Sudarshan Kriya yoga in MDD demonstrated an antidepressant response in untreated, hospitalized inpatients randomized to SKY (n=15), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT, n=15) or imipramine (IMN, n=15) 14. Significant improvements in HDRS-17 and BDI total scores were found for all three groups. The SKY group demonstrated HDRS-17 improvements comparable to IMN and less than ECT. Additional studies of SKY in dysthymic disorder,12 depression due to alcohol dependence13 and depression co-morbid with generalized anxiety disorder27 have demonstrated antidepressant efficacy. Direct comparisons between small studies with different patient populations must be made with caution due to methodological differences. However, the robust improvement in both HDRS-17 and BDI total scores reported in these studies are consistent with the outcomes of the current study.

In this study, the SKY intervention was delivered in two phases with a significant upfront time-commitment and resources required during the first week. During the second phase (Weeks 2–8), the weekly SKY follow-up sessions and the home practice required relatively less time and resources. For the purposes of feasibility, subjects were allowed to potentially miss one session during the first phase, and two follow-up sessions during the second phase of the intervention. Additionally, all sessions were held in the evenings to minimize conflicts with school or work. Of the ITT sample, 20/25 subjects had additional school or work during the two month study period. These findings, along with the subject completion rate (77%), support the feasibility of the SKY intervention for MDD outpatients.

Limitations of the current study include the small sample size, lack of an active comparator group and potential inclusion of subjects without optimized prospective antidepressant treatment. Perhaps most importantly, subjects assigned to the waitlist control condition obtained essentially no benefit during the 8 week wait to begin the intervention, i.e., an outcome that is not typical of patients receiving attention-placebo interventions. Further, although our independent raters did not know what treatment the subjects received, the subjects were not blind. In addition, outcomes may have reflected the fact that the SKY group received substantial clinical contact and group support, which can produce nonspecific treatment benefits. However, it is unlikely that these factors would explain the degree or duration of improvement following SKY in this severely depressed patient population. Similarly, while all subjects regardless of group assignment were offered the intervention, we did not formally assess how subject perception of intervention might impact study outcomes. Future studies, which differentiate the effects of the yoga intervention versus an active comparator group, are needed. With the establishment of short-term efficacy and safety, subsequent studies can assess long-term efficacy, particularly to identify the optimal duration of adjunctive SKY therapy.

In summary, an outpatient program of Sudarshan Kriya yoga demonstrated efficacy as an adjunctive to medication treatment in a randomized, waitlist-controlled pilot study, which included only patients who had inadequate response to ≥8 weeks of antidepressant treatment. The intervention was well tolerated in MDD outpatients. Future efforts to evaluate SKY in MDD may foster integration of novel yoga-based interventions in the treatment of this debilitating disorder.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Points.

Well-designed clinical studies that assess yoga interventions in the context of standard care in MDD are needed.

For patients with MDD with inadequate response to antidepressants, Sudarshan Kriya yoga offers a promising adjunctive treatment.

Acknowledgments

Funding/support: Financial support provided by the American Psychiatric Association/Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Minority Fellowship Program and the Indo-American Psychiatric Association. Financial support for CTRC personnel supported by Grant Number UL1TR000003 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

We would like to thank yoga instructors Ronnie Newman, Ed M, Jennifer Stevenson, BS, Sandeep Karode, PhD, Madhuri Karode, BS and Annelies Richmond, BA; MADTRP raters Golkoo Hosseini, MD, Mary Foley, MS, Frank Rose, BS, Tamar Halpern, BA and Katie Smith, MA and UPENN CTRC staff for participant scheduling and logistics including Joanne Burke, BSN, Domenick Salvatore, CSCS and Eric Nelson, BA. No conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of NCATS or the NIH.

Previous Presentation: 54th American College of Neuropsychopharmacology Meeting, December 9th, 2015, Hollywood, Florida

Potential conflicts of interest: Dr. Thase has received grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Alkermes, Forest, National Institute of Mental Health, Otsuka, PharmaNeuroboost and Roche; has acted as an advisor or consultant for Alkermes, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cerecor, Eli Lilly, Forest, Gerson Lehman Group, GlaxoSmithKline, Guidepoint Global, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, Neuronetics, Novartis, Ortho-McNeil, Otsuka, Pamlab, Pfizer, Shire, Sunovion and Takeda. Drs. Sharma, Barrett, Cucchiara and Gooneratne have no potential conflicts to disclose.

Role of sponsors: The sponsors provided funding support. The authors were responsible for study design, conduct and collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data. All authors were responsible for writing or reviewing this article and approved the final version.

References

- 1.Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website; [Accessed December 15, 2015]. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Medicine. 2013;10(11):e1001547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC. The costs of depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luppa M, Heinrich S, Angermeyer MC, et al. Cost-of-illness studies of depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;98(1–2):29–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olchanski N, McInnis Myers M, Halseth M, et al. The economic burden of treatment resistant depression. Clin Ther. 2013;35(4):512–22. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly KR, Thase ME. If at first you don’t succeed: A review of the evidence for antidepressant augmentation, combination and switching strategies. Drugs. 2011;71(1):43–64. doi: 10.2165/11587620-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paykel ES, Ramana R, Cooper Z, et al. Residual symptoms after partial remission: An important outcome in depression. Psychological Medicine. 1995;25(6):1171–80. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warden D, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. The STAR*D project results: A comprehensive review of findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(6):449–59. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balasubramaniam M, Telles S, Doraiswamy PM. Yoga on our minds: A systematic review of yoga for neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:1–16. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown RP, Gerbarg PL. Sudarshan kriya yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression: Part I-neurophysiologic model. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11(1):189–201. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown RP, Gerbarg PL. Sudarshan kriya yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression. Part II--clinical applications and guidelines. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11(4):711–7. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janakiramaiah N, Gangadhar BN, Naga Venkatesha Murthy PJ, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of sudarshan kriya yoga (SKY) in dysthymic disorder. Nimhans Journal. 1998;16(1):21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vedamurthachar A, Janakiramaiah N, Hegde JM, et al. Antidepressant efficacy and hormonal effects of sudarshana kriya yoga (SKY) in alcohol dependent individuals. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;94(1–3):249–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janakiramaiah N, Gangadhar BN, Naga Venkatesha Murthy PJ, et al. Antidepressant efficacy of sudarshan kriya yoga (SKY) in melancholia: A randomized comparison with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and imipramine. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2000;57(1–3):255–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma H, Sen S, Singh A, et al. Sudarshan kriya practitioners exhibit better antioxidant status and lower blood lactate levels. Biological Psychology. 2003;63(3):281–91. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(03)00071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma A, Newberg A. Mind-Body Practices and the Adolescent Brain: Clinical Neuroimaging Studies. Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;5(2):116–124. doi: 10.2174/2210676605666150311223728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams JB. A structured interview guide for the hamilton depression rating scale. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45(8):742–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800320058007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snow G. [Accessed: October 1, 2014];blockrand: Randomization for block random clinical trials. 2013 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=blockrand.

- 20.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. San Antonio: Harcourt Brace and Company; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox J, Weisberg S. An R Companion to Applied Regression. 2. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S. 4. New York: Springer; 2002. pp. 111–111. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, et al. [Accessed: December 1, 2015];nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. 2014 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme.

- 26.Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P. Simultaneous Inference in General Parametric Models. Biometrical Journal. 2008;50(3):346–363. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doria S, de Vuono A, Sanlorenzo R, et al. Anti-anxiety efficacy of Sudarshan Kriya Yoga in general anxiety disorder: A multicomponent, yoga based, breath intervention program for patients suffering from generalized anxiety disorder with or without comorbidities. Journal of affective disorders. 2015;184:310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.