Canada's new public health agency will track Clostridium difficile infections in 25 teaching hospitals across the country, after Quebec acknowledged an “epidemic” of infections in Montréal and surrounding hospitals.

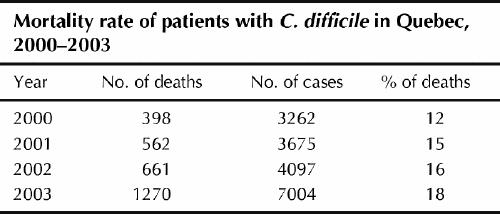

There were 7004 cases of C. difficile across Quebec from Apr. 1, 2003, to Mar. 31, 2004, and 1270 people died after contracting the nosocomial infection, according to data generated by Med-Echo, the provincial hospitalization database. The data were obtained from a presentation that Colette Gaulin of the Quebec Health Ministry's office of epidemiological surveillance made to microbiologists in September (see Table on next page).

Table 1

The Med-Echo data reveal a dramatic increase in the number of C. difficile infections among hospitalized patients in all regions of Quebec. Between March 2000 and April 2004, the number of cases doubled from 3262 to 7004. In addition, there was a 60% increase in the number of deaths associated with C. difficile infection. In 2000/01, 398 of 3262 hospitalized people with C. difficile (12%) died. By 2003/04, this increased to 7004 people, of which 1270 died (18%).

In an interview, Gaulin cautioned that while the data indicate an increased number of deaths, “that's all we can say.” The patients had C. difficile, “but we don't know if the death is associated or related because people can die [from] another disease,” she said.

Until now, physicians and hospitals have not been required to report nosocomial infections such as C. difficile to public health authorities. Earlier this summer, after CMAJ broke the news about infections in Montréal and Calgary, Manitoba announced it would be the first province to require mandatory reporting (CMAJ 2004;171 [1]: 19-21; 171 [1]: 33-8; 171[5]: 466-72). Ontario is also considering the need to add C. difficile infection to its list of reportable diseases.

The Public Health Agency of Canada will track the infection at the hospitals as a pilot project until next March, says spokesperson Aggie Adamczyk.

But infection-control experts in Montréal and elsewhere say tracking the numbers is only the first step toward controlling the outbreaks. Hospitals also need the resources for infection control, says Dr. Charles Frenette, who heads a new task force in Quebec formed to tackle the epidemic.

“Local administrations have to pump up their infection control nurse ratio so it is at least 1 per 133 acute care beds, which is not the case presently,” Frenette told CMAJ. He believes the hospitals need more funds from the province dedicated specifically for that purpose.

Quebec Health Minister Philippe Couillard responded to the data about caseloads and deaths by speculating that Quebec's “enthusiastic” prescribing of antibiotics might be the reason behind the C. difficile outbreaks in the province.

“We are, by far, the province that prescribes the largest quantities of antibiotics,” he told a news conference. Couillard also announced the creation of infection-control committees that will travel to hospitals to advise them about hand-washing, disinfection, isolation and other techniques to try to control the infection. A few days earlier, the minister had confirmed the caseload figure.

“Quebec is making every possible effort to limit or even diminish the seriousness of this scourge that is currently affecting our hospitals,” Couillard said then. “This is a serious problem.”

Microbiologists promptly held their own news conference, to argue that there are not enough private rooms in existing hospitals to properly isolate patients.

“Local experts already know what to do,” said Marie Goudreau, a doctor with Montréal's public health department. “The problem is that they don't always have the support or the resources to do it.”

The Quebec Health Ministry and infection control efforts were initially responding to a Radio-Canada news report based on the Med-Echo data that caused a furor in the Quebec medical establishment on Oct. 20 when it revealed the high number of cases and deaths. Headlines generated by the report prompted Dr. Vivian Loo, the lead infection control specialist in a Montréal group assembled to study the outbreak, to quickly present her findings.

Loo, at the Montreal University Health Centre, confirmed that in a narrower window of time — from January to June of this year — 217 patients died at 10 area hospitals after contracting C. difficile infection in those hospitals. Of that number, C. difficile was directly responsible for 109 deaths and contributed to another 108 deaths, Loo said. Colectomies were performed on another 33 people with the infection. In total, there were 1621 cases of C. difficile infection in 12 Montréal-area hospitals during that 6-month period. Two of those hospitals have not yet submitted their figures on deaths and colectomies.

“I would say this is a hospital-based epidemic, not an epidemic in the community,” Loo told CMAJ.

Increasing numbers of C. difficile cases began showing up in Montréal at the end of 2002, says Loo. The mortality rate for patients with C. difficile during the period she tracked was 8.6% in the 12 hospitals she studied.

“C. diff would rank as Number 1 in terms of superbugs like VRE and MRSA,” Loo said. “It's more virulent than MRSA.”

By sending samples from Montréal hospitals to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Loo confirmed that the strain of C. difficile active in Quebec is the same strain responsible for increased mortality in outbreaks in the US. Both Loo and the CDC experts believe the strain is more virulent than those circulating before the end of 2002, and that the US outbreaks predated those in Montréal.

“It's remarkable that you have such a closely related strain, geographically dispersed,” says Dr. Cliff McDonald, an epidemiologist who specializes in hospital-acquired infections at the CDC.

Currently, C. difficile infection rates at the Montreal University Health Centre, where Loo works, are down to 12 cases per 1000 patients admitted, close to the baseline of 8–10 cases per 1000, says Loo. But because the caseload has previously increased in the winter months, she is not yet confident the danger for patients has passed.

“I'm not holding my breath. We're still quite cautious,” Loo says. “Really the coming months will be a test of whether the measures we've put in place will control it further.” — Laura Eggertson, CMAJ

Figure. Dr. Loo: C. diff ranks as the Number 1 superbug Photo by: Canapress, R. Remiorz

Footnotes

Published at www.cmaj.ca on Nov. 2, 2004.