Abstract

Maintaining adequate oxygenation during one-lung ventilation (OLV) requires high inspired oxygen fraction (FiO2). However, high FiO2 also causes inflammatory response and lung injury. Therefore, it remains a great interest to clinicians and scientists to optimize the care of patients undergoing OLV. The aim of this study was to determine and compare oxygenation, inflammatory response and lung injury during OLV in rabbits using FiO2 of 0.6 vs. 1.0. After 30 minutes of two-lung ventilation (TLV) as baseline, 30 rabbits were randomly assigned to three groups receiving mechanical ventilation for 3 hours: the sham group, receiving TLV with 0.6 FiO2; the 1.0 FiO2 group, receiving OLV with 1.0 FiO2; the 0.6 FiO2 group, receiving OLV with 0.6 FiO2. Pulse oximetry was continuously monitored and arterial blood gas analysis was intermittently conducted. Histopathologic study of lung tissues was performed and inflammatory cytokines and the mRNA and protein of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) p65 were determined. Three of the 10 rabbits in the 0.6 FiO2 group suffered hypoxemia, defined by pulse oximetric saturation (SpO2) less than 90%. Partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2), acute lung injury (ALI) score, myeloperoxidase (MPO), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), mRNA and protein of NF-κB p65 were lower in the 0.6 FiO2 group than in the 1.0 FiO2 group. In conclusion, during OLV, if FiO2 of 0.6 can be tolerated, lung injury associated with high FiO2 can be minimized. Further study is needed to validate this finding in human subjects.

Keywords: one-lung ventilation, oxygen, acute lung injury, rabbits

Introduction

There are tremendous cases of general thoracic surgery requiring one lung ventilation (OLV) each year. One of the major challenges for clinicians is to maintain adequate oxygenation during OLV[1]. This could be achieved by providing high inspired oxygen fraction (FiO2) at FiO2 of 1.0. However, it is also well known high FiO2 is associated with many complications, including pneumonia, empyema, lung atelectasis, sepsis, and acute lung injury (ALI)[2–4]. These pulmonary complications contribute significantly to surgical risks and anesthesia, with a major impact on outcome and financial burden to the health system[5]. Therefore, minimizing lung injury has been a clinical focus in management of patients undergoing general thoracic surgery, particularly of those receiving OLV.

Recently, some protective ventilation strategies which have been widely used in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome also have been found beneficial in OLV. Some of these studies include low FiO2 into their protective ventilation strategy[6]. Della et al. suggested that FiO2 = 1.0 during OLV should be avoided[7]. However, the protective effect of low FiO2 has not been systemically evaluated even it showed some benefit. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that pathologic changes associated with high FiO2 are similar to other forms of ALI, and oxygen toxicity occurs even during OLV[8-9].

Since the severity of hyperoxic acute lung injury (HALI) is directly proportional to partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) (particularly above 450 mmHg, or FiO2 higher than 0.6) and duration of exposure[10], FiO2 less than or equal to 0.6 is usually considered to be safe in two lung ventilation (TLV)[11]. However, it remains unclear if 0.6 FiO2 is safe for OLV even if it is safe for TLV. It has been of great interest to determine the optimal FiO2 during OLV where both lung injuries associated with high FiO2 and the complications resulted from low FiO2 are maximally reduced. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine and compare oxygenation, inflammatory response, and lung injury during OLV in rabbits using FiO2 of 0.6 vs. 1.0. We hope that the results of this study will help clinicians to optimize the care of patients undergoing OLV.

Materials and methods

Animals and ethics

Thirty healthy New Zealand white rabbits (1.9-2.4 kg, either gender, purchased from Jinling Zhongtu Company, Nanjing, China) were used in this study. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Animal Experimentation of the authors' affiliated hospital.

Experimental protocols

A 24 G intravenous (IV) angiocatheter (BD intravenous cannula, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Singapore) was inserted into the right auricular vein for intravenous fluid and drug administration. The rabbits were anesthetized with 30% urethane IV (4 mL/kg of loading dose, followed by continuous infusion at a rate of 5-8 mL/(kg×hour) until tracheotomy was completed, and then continuous infusion was maintained throughout the entire experiment at a rate of 1 mL/(kg×hour) after tracheotomy). Afterwards, the rabbits were placed in the supine position. Pulse oximetric saturation (SpO2) was continuously monitored with the disposable SpO2 sensor on the left ear (pediatric disposable SpO2 sensor, Shenzhen Teveik Technology Co., Ltd, Shenzhen, China). Ringer's solution was infused at 10 mL/kg/hour continuously throughout the procedure. Tracheotomy was performed in the supine position aseptically at the level of 2-3 tracheal cartilage using a midline incision after infiltration with 1 mL of 2% lidocaine at incision site. Cisatracurium was given intravenously at a loading dose of 2 mg/kg and then infused at 2 mg/(kg×hour) throughout the procedure. An uncuffed endotracheal tube (3.0 mm, Mallinckrodt Medical, Athlone, Ireland) was inserted into the trachea (depth = 4 cm) through tracheotomy. After breathing sound and peak airway pressure (Ppeak) were checked, the trachea was tied to prevent air leak and tube dislodgement, and then mechanical TLV was started (DW3000B small animal ventilation machine, ZS Dichuang Development of Science and Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) using volume controlled mode, tidal volume (VT) = 10 mL/kg, respiratory rate (RR) = 40 breaths/minute, inspiratory: expiratory ratio (I:E) = 1:2, FiO2 of 0.6, and zero positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP). The right femoral artery was cannulated (22, or 24 G, BD arterial cannula, Becton, Dickinson and Company) for arterial blood pressure and arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis. Room temperature was set at 25°C.

After baseline data was collected after 30 minutes of TLV, 30 rabbits were randomly assigned to three groups: TLV with 0.6 FiO2 (the sham group), OLV with 1.0 FiO2 (the 1.0 FiO2 group), and OLV with 0.6 FiO2 (the 0.6 FiO2 group). Ventilation was continued for 3 hours in each group (n = 10). The ventilatory settings were as those of the baseline TLV: volume controlled ventilation, VT = 10 mL/kg, RR = 40 breaths/minute, I:E = 1:2, and PEEP = 0 cm H2O. OLV was carried out by isolating the left lung with customized bronchial blocker. Breathing sound and Ppeak were checked and fiberscope (FI-9RBS Portable Intubation Fiberscope, Pentax, Canada) was also used to ensure the appropriate positioning of the tube. Then, the rabbits were placed in the right lateral position and ventilation was continued in this position for 3 hours. Tube position was checked every 30 minutes. Vital signs including blood pressure (BP), and heart rate (HR) were monitored by a standard anesthesia monitoring system (PM-9000 Express Patient Monitor, Mindray Medical International Limited, China), and arterial blood sample was measured (i-STAT portable clinical analyzer, Abbott Laboratories, USA) for PaO2, arterial hemoglobin oxygen saturation (SaO2), PaO2/ FiO2, acidity (pH), partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) at baseline (t = 0), 10 minutes (t = 10 minutes), 30 minutes (t = 30 minutes), 1 hour (t = 1 hour), 2 hours (t = 2 hours), and 3 hours (t = 3 hours). At the end of 3 hours (endpoint), the rabbits were sacrificed by quick bleeding after anesthesia was deepened with boluses of urethane. The correct position of the endotracheal tube (the sham group) or blocker (the 0.6 FiO2 group and 1.0 FiO2 group) was eventually confirmed at the end of the experiment by autopsy and bronchial dissection. Lung tissue specimens were surgically obtained immediately which included 2 trimmed lung-tissue blocks (1.5 × 1 × 0.3 cm3) from the same site of both lungs. One tissue block was fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin; the other was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for the measurement of inflammatory cytokines and mRNA and protein level of NF-κB p65.

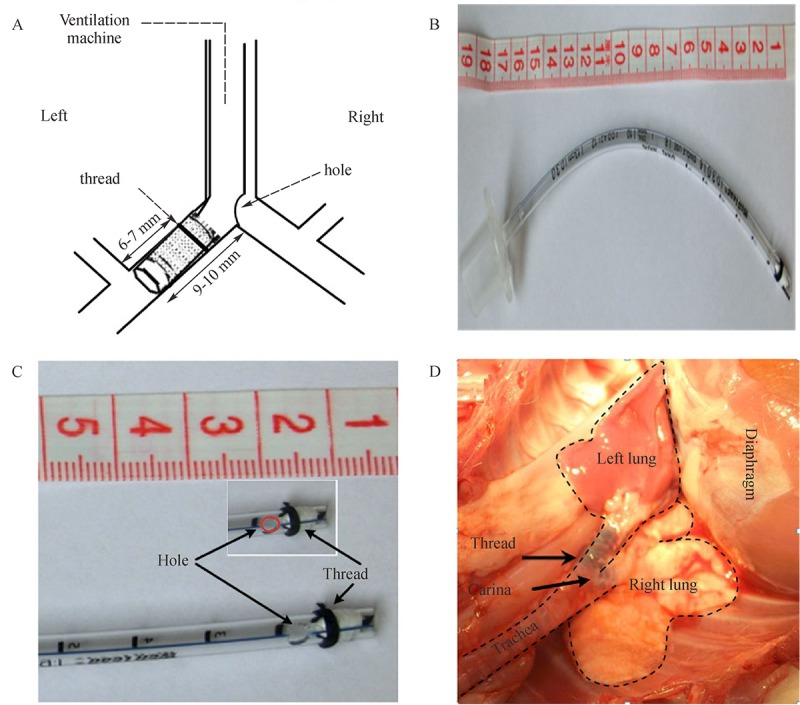

Lung isolation

Left lung isolation was achieved by advancing the customized bronchial blocker into the left main bronchus. The end of the blocker was sealed to block the left lung, and approximately 9-10 mm from the tip of the blocker, an opening was created to face the opening of the right main bronchus, thus to ventilate only the right lung. The detailed description was provided in our previous study[12] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Demonstration of the customized bronchial blocker16.

A: Dimensions of the customized bronchial blocker. B: A photograph of the customized bronchial blocker. C: Major details of the customized bronchial blocker. D: In vivo right-one lung ventilation (OLV) model created with the customized bronchial blocker.

Histopathologic examination

The paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were sliced at a thickness of 5 μm for histopathologic examination. Routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed on each section for histopathologic examination, which was evaluated by two individual pathologists who were not from the study team. Random fields from each slide were digitally imaged for qualitative analysis (BX40, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and photographed with a Panasonic WV-CP450 camera (Panasonic, Osaka, Japan).

Lung injury was scored on the basis of the following four morphological features: (1) alveolar congestion, (2) hemorrhage, (3) infiltrations or aggregations of neutrophils in the airspace or the vessel wall, and (4) thickness of the alveolar wall/hyaline membrane formation. Each category was graded using a five-point scale, as described previously: 0 = minimal (little) damage, 1 = mild damage, 2 = moderate damage, 3 = severe damage and 4 = maximal damage[13].

ELISA

The levels of myeloperoxidase (MPO), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in lung homogenates were measured using the Rabbit ELISA Assay Kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Technique of quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay was employed which was described previously[14].

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from lung tissues of rabbits using Trizol reagent (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China). One μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed to generate cDNA using RNA PCR Kit (RR047, Takara) strictly according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then, amplification was carried out in a total volume of 25 μL containing 0.5 μL of each primer, 12 μL SybrGreen qPCR Master Mix (Ruian BioTechnologies Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and 2 μL of 1:12.5 diluted cDNA. Standard curves and quantitative real-time PCR results were analyzed using ABI7900 software (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA, USA). The primer sequences are listed as follows: Forward: 5′-AGCCCACCACTCCTTCTAT-3′, Reverse: 5′-GTATCTGCAGGGTGTCCATATC-3′ for NF-κB p65; Forward: 5′-AAGGTCGGAGTGAACGGATTTG-3′, Reverse: 5′-CGTGGGTGGAATCATACTGGAAC-3′ for GAPDH. Expression data were normalized to the geometric mean of housekeeping gene GAPDH to control variability in expression levels and analyzed using the 2-△△CT method.

Preparation of nuclear extracts

Nuclear extracts of lung tissues were prepared by hypotonic lysis followed by high salt extraction[15]. Briefly, 50 mg frozen lungs were homogenized in 0.5 mL ice-cold buffer A, composed of 10 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.9), 10 mmol/L KCl, 2 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.1 mmol/L EDTA, 1.0 mmol/L dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.5 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonylfluoride (PMSF) (all from Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The homogenate was incubated on ice for 15 minutes, after which 50 μL of 10% Nonidet P-40 solution was added; the mixture was vortexed for 30 seconds and centrifuged for 1 minute at 6,000 g at 4°C. The crude nuclear pellet was resuspended in 200 μL of buffer B, containing 20 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.9), 420 mmol/L NaCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L DTT, 0.5 mmol/L PMSF, and 25% (v/v) glycerol, and was incubated on ice for 30 minutes with intermittent mixing. The suspension was centrifuged at 12,000 g at 4°C for 15 minutes. The supernatant containing the nuclear proteins was collected and kept at -80°C. The protein concentration was measured according to the Bradford procedure.

Western blotting method

Western blotting assays were performed according to standard procedures. Briefly, protein (50 μg) were separated on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The samples was blocked by 5% milk in TBST (Tris buffered saline and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 hour at room temperature, and then incubated with primary antibody against p65 subunit of NF-κB (1:1,000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 hours. After three washes with TBS, the detected bands were quantified using UVP EC3 Imaging System (UVP, Upland, CA, USA). β-actin was used as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean±SD for quantitative variables, and ALI scores were presented as mean rank. Quantitative variables were analyzed by the general linear model followed by multivariate test, and ALI scores were analyzed by the general linear model followed by univariate test after rank transformation. All statistical analyses were carried out by using the SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

There were no significant differences among the three groups of rabbits in terms of weight, total dose of urethane and cisatracurium, total volume of Ringer's solution (Table 1). HR and MAP showed no differences among the three groups. Ppeak increased significantly after OLV in both the 0.6 FiO2 and 1.0 FiO2 group compared with that of the sham group, but there were no differences between the 0.6 FiO2 and 1.0 FiO2 group (Table 2).

Table 1.

Weight of the rabbits and total usage of urethane, cisatracurium, and Ringer's solution

| Sham (n = 10) |

1.0 FiO2 (n = 10) |

1.0 FiO2 (n = 10) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 2.06±0.14 | 2.08±0.14 | 2.10±0.13 |

| Urethane (g) | 19.2±2.3 | 18.4±2.0 | 20.1±2.4 |

| Cisatracurium (mg) | 11.1±1.1 | 11.3±1.8 | 12.1±3.0 |

| Ringer's solution (mL) | 118±11 | 110±14 | 116±11 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD (standard deviation). There were no differences among the three groups, P > 0.05.

Table 2.

Peak pressure (Ppeak), heart rate (HR), and mean arterial pressure (MAP) over time.

| Group | 0 | 10 minutes | 30 minutes | 1 hour | 2 hours | 3 hours | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ppeak (kpa) | Sham | 1.64±0.16 | 1.69±0.18 | 1.63±0.11 | 1.67±0.09 | 1.68±0.11 | 1.68±0.12 |

| 1.0 FiO2 | 1.65±0.26 | 2.05±0.23* | 2.04±0.27* | 2.10±0.32* | 2.05±0.39* | 2.13±0.43* | |

| 0.6 FiO2 | 1.68±0.07 | 1.91±0.13* | 1.94±0.09* | 1.93±0.17* | 1.96±0.21* | 1.97±0.13* | |

| HR (/minute) | Sham | 241±28 | 236±26 | 227±19 | 222±20 | 208±25 | 209±25 |

| 1.0 FiO2 | 225±21 | 234±23 | 236±16 | 221±13 | 214±29 | 199±28 | |

| 0.6 FiO2 | 243±13 | 223±14 | 227±16 | 218±13 | 219±30 | 207±29 | |

| MAP (mmHg) | Sham | 77±10 | 78±14 | 78±12 | 76±14 | 76±11 | 77±13 |

| 1.0 FiO2 | 69±12 | 74±12 | 72±12 | 73±11 | 71±11 | 73±8 | |

| 0.6 FiO2 | 76±12 | 72±11 | 74±10 | 76±10 | 79±9 | 79±11 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD (standard deviation). n = 10 in the sham and 1.0 FiO2 group, and n = 7 in the 0.6 FiO2 group. * P < 0.05 vs. the sham group.

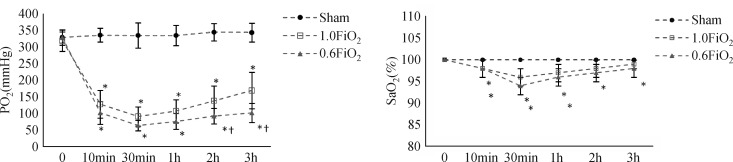

FiO2 of 0.6 decreased PaO2

Three rabbits in the 0.6 FiO2 group suffered hypoxemia and were excluded from the final analysis. No animal suffered hypoxemia in the 1.0 FiO2 group and the sham group. PaO2, SaO2, and PaO2/FiO2 in both the 0.6 FiO2 and 1.0 FiO2 group declined during OLV compared with those in the sham group (P < 0.05). PaO2 was lower at 2 hours and 3 hours of OLV in the 0.6 FiO2 group, than that in the 1.0 FiO2 group, while SaO2, PaO2/FiO2, acidity (pH), and PaCO2 showed no difference between the 0.6 FiO2 and 1.0 FiO2 group (Fig. 2, Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Effect of FiO2 on partial PaO2 and SaO2 over time.

This figure shows a lower mean PaO2 in the 0.6 FiO2 group at 2 hours and 3 hours of one lung ventilation (OLV), compared with those in the 1.0 FiO2 group. SaO2 shows no differences between the 0.6 FiO2 and 1.0 FiO2 group over time.* P < 0.05 vs. the sham group, † P < 0.05 vs. the 1.0 FiO2 group.

Table 3.

Partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2), arterial hemoglobin oxygen saturation (SaO2), arterial oxygen tension (PaO2)/ inspired oxygen fraction (FiO2), acidity (pH), and carbon dioxide tension (PaCO2) over time.

| Group | 0 | 10 minutes | 30 minutes | 1 hour | 2 hours | 3 hours | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PO2 (mmHg) | Sham | 329±23 | 336±21 | 335±38 | 335±30 | 345±26 | 344±28 |

| 1.0 FiO2 | 319±32 | 128±42* | 91±29* | 107±35* | 138±45* | 169±55* | |

| 0.6 FiO2 | 329±17 | 102±34* | 64±16* | 76±24* | 92±23*† | 102±29*† | |

| SaO2 (%) | Sham | 100±0 | 100±0 | 100±0 | 100±0 | 100±0 | 100±0 |

| 1.0 FiO2 | 100±0 | 98±2* | 96±2* | 97±2* | 98±2 | 99±1 | |

| 0.6 FiO2 | 100±0 | 98±2* | 94±2* | 96±2* | 97±2* | 98±2* | |

| PaO2/FiO2 | Sham | 549±39 | 560±35 | 558±64 | 559±51 | 575±43 | 573±46 |

| 1.0 FiO2 | 531±54 | 128±42* | 91±29* | 107±35* | 138±45* | 169±55* | |

| 0.6 FiO2 | 549±28 | 170±57* | 106±26* | 127±40* | 154±38* | 170±48* | |

| pH | Sham | 7.57±0.12 | 7.45±0.18 | 7.47±0.10 | 7.47±0.09 | 7.46±0.11 | 7.38±0.12 |

| 1.0 FiO2 | 7.60±0.12 | 7.49±0.09 | 7.44±0.10 | 7.40±0.09 | 7.39±0.08 | 7.39±0.08 | |

| 0.6 FiO2 | 7.59±0.10 | 7.52±0.11 | 7.47±0.07 | 7.44±0.06 | 7.42±0.03 | 7.43±0.06 | |

| PaCO2(mmHg) | Sham | 26±3 | 28±3 | 28±4 | 26±4 | 26±5 | 24±5 |

| 1.0 FiO2 | 25±3 | 27±3 | 30±4 | 30±6 | 29±4 | 27±4 | |

| 0.6 FiO2 | 27±2 | 27±4 | 29±4 | 29±4 | 29±4 | 25±3 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD (standard deviation). n = 10 in the sham and 1.0 FiO2 group, n = 7 in the 0.6 FiO2 group. * P < 0.05 vs. the sham group, †P < 0.05 vs. the 1.0 FiO2 group.

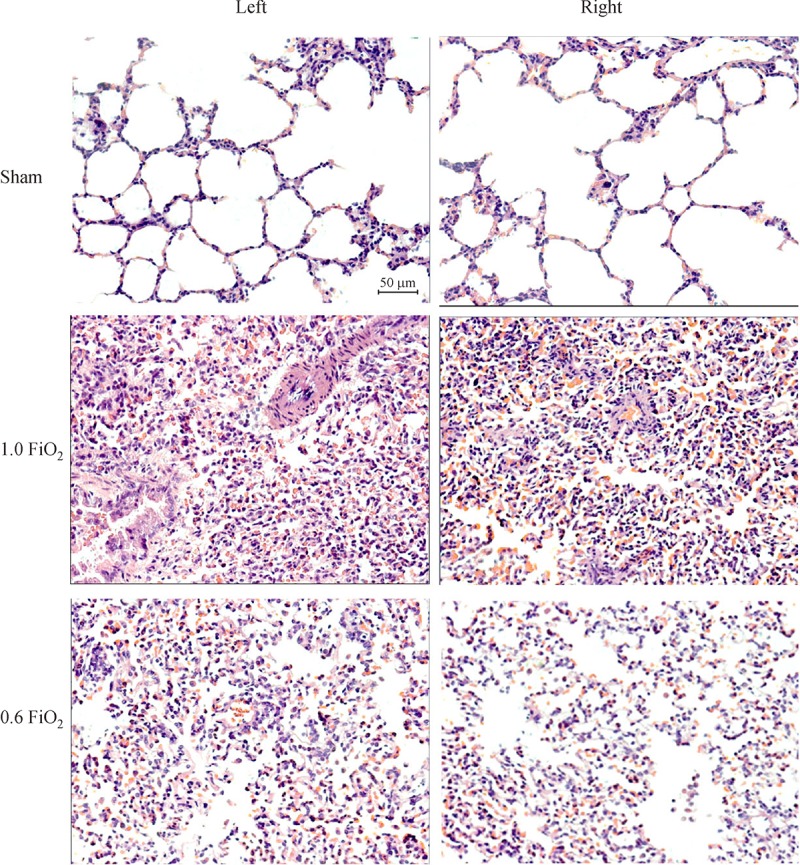

FiO2 of 0.6 alleviated lung injury in both ventilated and collapsed lungs

At 3 hours, the sham group showed nearly normal lung histology, while the 0.6 FiO2 and 1.0 FiO2 group showed extensive morphological lung injury with higher ALI score (P < 0.05). However, the 0.6 FiO2 group showed less edema, thickening of the alveolar wall, infiltration of inflammatory cells into alveolar space and interstitial space (Fig. 3) with lower ALI score (the left lung: 2.1±1.3 vs. 3.3±1.1, P < 0.05; the right lung: 2.3±1.1 vs. 3.4±0.7, P < 0.05), compared with the 1.0 FiO2 group.

Fig. 3.

Representative histological sections of both lungs at 3 hours.

There are less edema, thickening of the alveolar wall, and infiltration of inflammatory cells into the alveolar space and interstitial space in the 0.6 FiO2 group, with a lower ALI score (the left lung: 2.1±1.3 vs. 3.3±1.1, P < 0.05; the right lung: 2.3±1.1 vs. 3.4±0.7, P < 0.05), compared with those in the 1.0 FiO2 group. All photos are 200 magnifications.

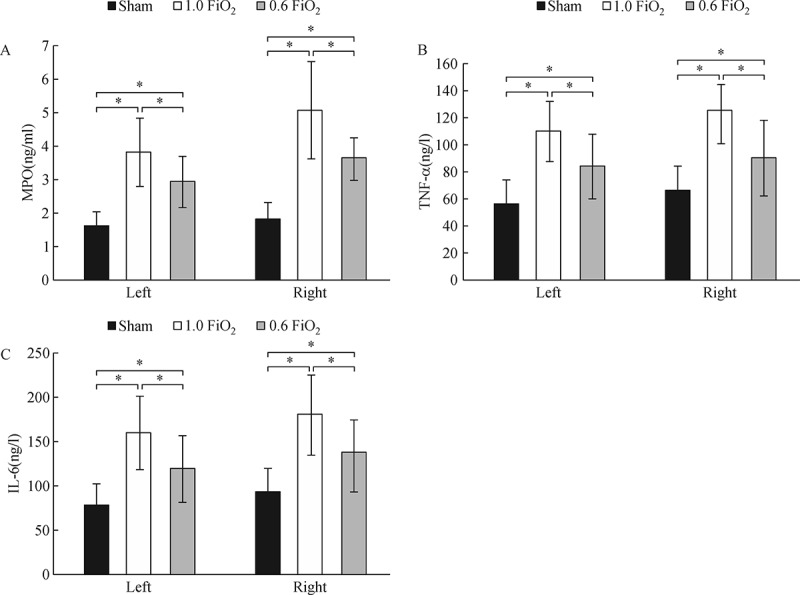

FiO2 of 0.6 alleviated inflammatory response in both ventilated and collapsed lungs

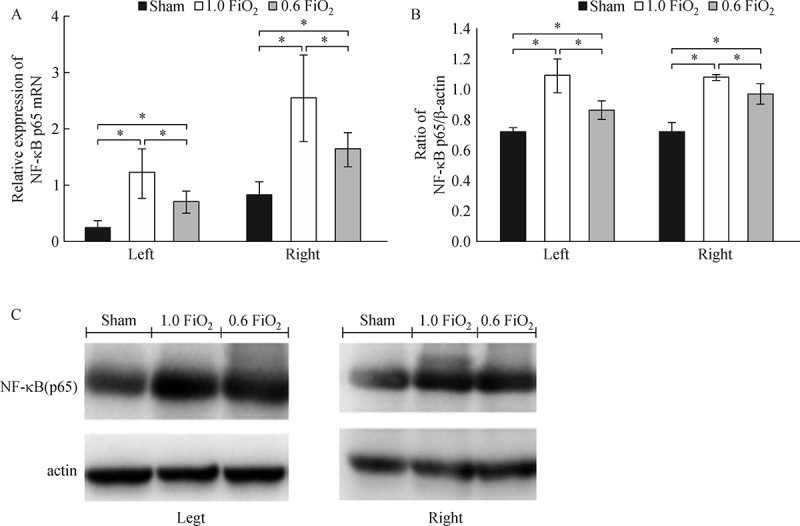

MPO, TNF-α and IL-6 of both lungs were higher in the 0.6 FiO2 and 1.0 FiO2 group at 3 hours, compared with the sham group, while these three indexes were lower in the 0.6 FiO2 group than those in the 1.0 FiO2 group (Fig. 4). The mRNA expression and protein level of NF-κB p65 in bilateral lungs were higher in the 0.6 FiO2 and 1.0 FiO2 group at 3 hours than those in the sham group, while lower in the 0.6 FiO2 group than those in the 1.0 FiO2 group (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO), tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in lung tissues.

Levels of MPO, TNF-α and IL-6 in lung tissue homogenates from the collapsed and ventilated lungs are higher in the 0.6 FiO2 and 1.0 FiO2 group at 3 hours, compared with the sham group, while they are lower in the 0.6 FiO2 group, compared with those in 1.0 FiO2 group. * P < 0.05.

Fig. 5.

The mRNA expression and protein level of NF-κB p65 in bilateral lung tissues.

The mRNA expression and protein level of NF-κB p65 in the bilateral lungs are higher at 3 hours in the 0.6 FiO2 and 1.0 FiO2 group, compared with the sham group, while they are lower in the 0.6 FiO2 group, compared with those in the 1.0 FiO2 group. * P < 0.05.

Discussion

In this rabbit model using a randomized approach, we found that 70% rabbits were able to maintain SpO2 at or greater than 90% with FiO2 of 0.6 during OLV and with FiO2 of 0.6, the lung injury of the animals was significantly reduced compared with those using FiO2 of 1.0. To our knowledge, this is the first animal study demonstrating that lung injury during OLV can be minimized by lowering FiO2 if oxygenation is not significantly compromised.

Clinicians are well aware that the benefit of high FiO2 during OLV to maintain adequate oxygenation, because of the high rate of desaturation events with low FiO2[16]. However, the complications associated with high FiO2 are also well known which include pneumonia, empyema, lung atelectasis, sepsis, and ALI. Many studies have shown that toxicity increases rapidly as FiO2 is greater than 0.6. The injury is also time sensitive[10]. In the past decade, several studies have demonstrated that ALI is caused by combined effects of hyperoxia and mechanical lung-stretch, suggesting either an additive or synergistic effect of high VT and hyperoxia, and the risk of HALI is minimal when the FiO2 is≤0.6[17–20].

However, not so many experiments have focused on FiO2 during OLV. Some studies showed that hypoxemia during OLV, defined by a decrease in SaO2 to less than 90%, occurred in 4-10% of patients[21–22]. Yang et al. [6] found that during OLV, 58% of the patients needed to increase FiO2 from 0.5 to maintain SpO2 > 95%. In our study, hypoxemia occurred in three of the ten rabbits in the 0.6 FiO2 group, which indicated that exposure to 0.6 FiO2 significantly increased the risk of hypoxemia compared with 1.0 FiO2.

However, those rabbits in the 0.6 FiO2 group which did not suffer hypoxemia showed less edema, thickening of the alveolar wall, and infiltration of inflammatory cells into the alveolar space and interstitial space with a lower ALI score with alleviated lung inflammatory response at 3 hours of OLV, compared to those in the 1.0 FiO2 group.

We cannot ignore the disadvantage of low FiO2 as three of the ten rabbits could not maintain SpO2≥90%. We would emphasize that those that could tolerate 0.6 FiO2 did benefit from low FiO2 and demonstrated reduction in lung injury. To extrapolate this finding in clinical setting, the majority of patients undergoing OLV can receive 0.6 FiO2 safely. The remaining patients who could not tolerate low FiO2 can be managed with certain techniques such as CPAP on the non-ventilated lung, PEEP on the ventilated lung and others[23–24]. If application of these techniques is unable to achieve adequate oxygenation, greater FiO2 may be used. On the other hand, our results also indicated that the protective effect of low FiO2 was diminished if adequate oxygenation was not achieved. Therefore, in clinical practice, clinicians must ensure that the arterial oxygen saturation is not lower than 90% when low FiO2 is applied.

There are several limitations of this study. First, we did not study the full spectrum of protective effects and rather chose arbitrarily FiO2 of 0.6 and 1.0. This is mainly due to the limitation of our funding availability. However, our result can be extrapolated that the protective effect of FiO2 of 0.8 is likely between those of FiO2 0.6 and 1.0. Therefore, our finding is still meaningful even though the entire spectrum of the FiO2 effect was not illustrated. Second, we chose a few parameters of lung injuries. Other studies also include different inflammatory cytokines, e.g. IL-1, 8, 10, 12, etc. [25–27]. However, we believe that the parameters we chose were sufficient to reveal lung injuries.

Third, we chose only right OLV in this experiment as it is easier to isolate the left lung in rabbit. We assume the difference in lung tissues between the left and right lung is minimal and the response to low FiO2 and hypoxia is comparable between the two lungs. Finally, we arbitrarily chose the duration of OLV 3 hours. We assumed that 3 hours represented the typical clinical scenario of major thoracic surgery. The trajectory of PaO2 during OLV was reported to decrease to the minimum within 1 hour, and then gradually increase after the minimum[28]. Our preliminary work (Supplementary Data) and other research showed that the ALI from OLV is time-related, which means more serious injury with longer OLV duration, and lung injury had already been detected at 3 hours of OLV[29]. Therefore, the effect of low FiO2 protection and hypoxia could be well presented in the 3-hour OLV model.

In conclusion, our present study showed that FiO2 of 0.6 provides adequate oxygenation in the majority of rabbits during OLV. If adequate oxygenation can be achieved with low FiO2, lung injury associated with hyperoxia can be minimized. Further study is needed to validate if our finding is reproducible in human subjects and if application of this approach positively impacts the outcome of patients undergoing OLV.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from Department of Anesthesiology, Jiangsu Cancer Hospital. The authors thank our colleague, epidemiologist Suping Li, for the guidance of statistical work in this study.

References

- [1].Kim KN, Kim DW, Jeong MA, et al. Comparison of pressure-controlled ventilation with volume-controlled ventilation during one-lung ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. BMC Anesthesiol, 2016, 16(1): 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hopf HW, Holm J. Hyperoxia and infection[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol, 2008, 22(3): 553–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Magnusson L, Spahn DR. New concepts of atelectasis during general anaesthesia[J]. Br J Anaesth, 2003, 91(1): 61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Licker M, Fauconnet P, Villiger Y, et al. Acute lung injury and outcomes after thoracic surgery[J]. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol, 2009, 22(1): 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].de Abreu MG, Pelosi P. How can we prevent postoperative pulmonary complications[J]? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol, 2013, 26(2): 105–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yang M, Ahn HJ, Kim K, et al. Does a protective ventilation strategy reduce the risk of pulmonary complications after lung cancer surgery?: a randomized controlled trial[J]. Chest, 2011, 139(3): 530–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Della Rocca G, Coccia C. Acute lung injury in thoracic surgery[J]. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol, 2013, 26(1): 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Royer F, Martin DJ, Benchetrit G, et al. Increase in pulmonary capillary permeability in dogs exposed to 100% O2[J]. J Appl Physiol (1985), 1988, 65(3): 1140–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Royston BD, Webster NR, Nunn JF. Time course of changes in lung permeability and edema in the rat exposed to 100% oxygen [J]. J Appl Physiol (1985), 1990, 69(4): 1532–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kallet RH, Matthay MA. Hyperoxic acute lung injury[J]. Respir Care, 2013, 58(1): 123–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Brower RG, Ware LB, Berthiaume Y, et al. Treatment of ARDS[J]. Chest, 2001, 120(4): 1347–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Xu ZP, Gu LB, Bian QM, et al. A novel method for right one-lung ventilation modeling in rabbits[J]. Exp Ther Med, 2016, 12(2): 1213–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].You Z, Feng D, Xu H, et al. Nuclear factor-kappa B mediates one-lung ventilation-induced acute lung injury in rabbits[J]. J Invest Surg, 2012, 25(2): 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tripsianis G, Papadopoulou E, Anagnostopoulos K, et al. Coexpression of IL-6 and TNF-α: prognostic significance on breast cancer outcome[J]. Neoplasma, 2014, 61(2): 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Liu D, Zeng BX, Shang Y. Decreased expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in endotoxin-induced acute lung injury[J]. Physiol Res, 2006, 55(3): 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Karzai W, Schwarzkopf K. Hypoxemia during one-lung ventilation: prediction, prevention, and treatment[J]. Anesthesiology, 2009, 110(6): 1402–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bailey TC, Martin EL, Zhao L, et al. High oxygen concentrations predispose mouse lungs to the deleterious effects of high stretch ventilation[J]. J Appl Physiol (1985), 2003, 94(3): 975–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sinclair SE, Altemeier WA, Matute-Bello G, et al. Augmented lung injury due to interaction between hyperoxia and mechanical ventilation[J]. Crit Care Med, 2004, 32(12): 2496–2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Makena PS, Gorantla VK, Ghosh MC, et al. Lung injury caused by high tidal volume mechanical ventilation and hyperoxia is dependent on oxidant-mediated c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation[J]. J Appl Physiol (1985), 2011, 111(5): 1467–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Li LF, Liao SK, Ko YS, et al. Hyperoxia increases ventilator-induced lung injury via mitogen-activated protein kinases: a prospective, controlled animal experiment[J]. Crit Care, 2007, 11(1): R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schwarzkopf K, Klein U, Schreiber T, et al. Oxygenation during one-lung ventilation: the effects of inhaled nitric oxide and increasing levels of inspired fraction of oxygen[J]. Anesth Analg, 2001, 92(4): 842–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Slinger P, Suissa S, Triolet W. Predicting arterial oxygenation during one-lung anaesthesia[J]. Can J Anaesth, 1992, 39(10): 1030–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fujiwara M, Abe K, Mashimo T. The effect of positive end-expiratory pressure and continuous positive airway pressure on the oxygenation and shunt fraction during one-lung ventilation with propofol anesthesia[J]. J Clin Anesth, 2001, 13(7): 473–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Michelet P, Roch A, Brousse D, et al. Effects of PEEP on oxygenation and respiratory mechanics during one-lung ventilation[J]. Br J Anaesth, 2005, 95(2): 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Komatsu Y, Yamamoto H, Tsushima K, et al. Increased interleukin-8 in epithelial lining fluid of collapsed lungs during one-lung ventilation for thoracotomy[J]. Inflammation, 2012, 35(6): 1844–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Leite CF, Calixto MC, Toro IF, et al. Characterization of pulmonary and systemic inflammatory responses produced by lung re-expansion after one-lung ventilation[J]. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth, 2012, 26(3): 427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sugasawa Y, Yamaguchi K, Kumakura S, et al. The effect of one-lung ventilation upon pulmonary inflammatory responses during lung resection[J]. J Anesth, 2011, 25(2): 170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ishikawa S.. Oxygenation may improve with time during one-lung ventilation[J]. Anesth Analg, 1999, 89: 258–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].You Z, Yao S, Liang H. Comparison of lung injury degrees after one-lung ventilation for different time[J]. Chin J Crit Care Med, 27(2): 133–135. [Google Scholar]