Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To compare outcomes of partial nephrectomy (PN) and radical nephrectomy (RN) in patients 65 years and older.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our institutional renal mass registry was queried for patients 65 and older with solitary cT1–T2 renal mass resected by PN or RN. Clinicopathologic features and perioperative outcomes were compared between groups. Renal function outcomes measured by change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and freedom from eGFR< 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 were analyzed. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard models for overall survival and cancer-specific survival were analyzed.

RESULTS

Overall, 787 patients met inclusion criteria. Of these, 437 (55.5%) underwent PN and 350 (44.5%) underwent RN. Median follow-up was 36 months. Patients in the PN cohort were younger (median age 70.3 years vs 71.9 years, P < .001), had lower American Society of Anesthesiologists scores (2.6 vs 2.8, P = .001), smaller tumors (tumor diameter 2.8 cm vs 5.0 cm, P < .001), and lower proportion of renal cell carcinoma (76.7% vs 87.4%, P < .001). Perioperative outcomes were similar between PN and RN groups as were complications (37.8% vs 38.9%). Estimated change in eGFR was less in PN vs RN (6.4 vs 19.7, P < .001) at last follow-up. Overall survival and cancer-specific survival were equivalent between modalities.

CONCLUSION

Because the renal functional benefit of PN is realized over many years and the procedure has a higher historical complication rate than RN, some suspected elderly patients might benefit more from RN over PN. However, these data suggest that elderly patients are not harmed and may potentially benefit from PN. Age alone should not be a contraindication to nephron-sparing surgery.

The incidence of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has been increasing with improved imaging and a growing aging population.1 RCC is most often diagnosed in the sixth to eight decade of life. Because individuals over the age of 65 now comprise the fastest-growing age group in the United States,2 the number of elderly patients diagnosed with RCC will likely continue to rise. The management of older adults who need surgery presents unique challenges, as the degree of aggressive management must be balanced with expected life expectancy, patient willingness, and urgency of the intervention. Relative to their younger counterparts, patients in the geriatric community have lower baseline kidney function, have more significant chronic systemic disease, and have greater difficulty with complications and recovery.3 Indeed, the risk of other-cause mortality among elderly patients with RCC is high.4

For patients with localized renal masses (cT1–T2), both partial nephrectomy and radical nephrectomy (PN and RN, respectively) are effective treatment options. However, PN is the preferred surgical treatment for most patients with cT1 renal masses for its added long-term renal function preservation benefit.5

An unanswered question in the treatment of elderly patients with renal masses is whether they live long enough to realize the benefit of nephron-sparing surgery.6 For this reason, many elderly patients are offered laparoscopic RN, which is historically associated with fewer complications and shorter return to convalescence.7–9 However, age-associated loss of kidney function predisposes older kidneys to acute kidney injury and progressive chronic kidney disease (CKD). The same amount of nephron loss can have even greater implications in older patients who already have decreased baseline function. It is therefore the objective of this study to compare oncologic, perioperative, and renal functional outcomes of renal cell tumors treated with PN or RN in the elderly population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our institutional review board-approved renal mass registry (2003–2015) was queried for patients with clinically localized (cT1-2N0M0) renal masses undergoing PN or RN in patients aged 65 or older at the time of surgery. Patients with solitary kidneys and bilateral tumors were excluded. Demographic, pathologic, operative, and postoperative information was obtained from the medical record.

Postoperative complications were evaluated within 90 days of the surgery, and classified using the Clavien-Dindo grading for surgical complications.10 The preoperative patients and operative and postoperative data were evaluated using comparative statistics (rank-sum for continuous data, Fisher’s exact for categorical data). Overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) were compared using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the impact of intervention type was determined by Cox proportional hazard regression, controlling for patient age, tumor diameter, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, and pathologic stage.

Follow-up for all patients with RCC included physical examination, chest imaging and cross-sectional abdominal imaging, and serum creatinine within 6 months after surgery and annually thereafter. CSS was calculated from the time of surgery to death from kidney cancer. An annual query of the Social Security Death Index is performed to confirm vital status and date of death for all patients. Survival analysis was limited to patients with RCC. Study end points were perioperative complications, change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at last follow-up, freedom from eGFR<45 mL/min/1.73 m2, OS, and CSS. Statistical analysis was performed with Stata 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Tumor Characteristics

A total of 787 patients were identified, 437 (55.5%) and 350 (44.5%) underwent PN and RN, respectively. Median follow-up for the entire cohort was 36 months (interquartile range [IQR] 14–70 months), and did not differ significantly between interventions (PN 32.9 [IQR 12.3–70.2] and RN 38.7 [IQR 15.4–68.5], P = .27). The patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Of note, the PN patients were younger than the RN patients (70.3 years vs 71.9 years, P < .001), had smaller tumor diameter (2.8 cm vs 5.0 cm, P < .001), had lower percentage of tumors found to be RCC (76.7% vs 87.4%, P < .001), and had a lower percentage of pT3a upstaged tumors (9.9% vs 33.7%, P < .001). Median Charlson comorbidity index was not significantly different between groups (1 vs 1, P = .63).

Table 1.

Demographics and tumor characteristics of patients undergoing partial nephrectomy and radical nephrectomy

| Overall | Partial Nephrectomy | Radical Nephrectomy | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 787 | 437 (55.5) | 350 (44.5) | |

| Age | 70.9 (67.6–76.0) | 70.3 (67.2–74.7) | 71.9 (68.2–77.5) | <.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 511 (64.9) | 283 (66.9) | 205 (61.6) | 0.15 |

| BMI | 28.2 (24.7–32.0) | 28.5 (25.3–32.0) | 27.3 (23.7–31.6) | .07 |

| ASA score (mean) | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.8 | .001 |

| CCI | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.63 |

| Tumor diameter (cm) | 3.6 (2.5–5.2) | 2.8 (2–4) | 5.0 (3.5–7) | <.001 |

| RCC, n (%) | 641 (81.5) | 335 (76.7) | 306 (87.4) | <.001 |

| RCC subtype, n (%) | .003 | |||

| Clear cell | 372 (58.7) | 177 (53.2) | 195 (64.8) | |

| Papillary | 157 (24.8) | 99 (29.7) | 58 (19.3) | |

| Chromophobe | 52 (8.2) | 28 (8.4) | 24 (8.0) | |

| Other | 60 (9.4) | 31 (9.3) | 29 (9.5) | |

| Pathologic T stage, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| pT1a | 319 (49.7) | 234 (69.9) | 85 (27.8) | |

| pT1b | 136 (21.2) | 53 (15.8) | 83 (27.1) | |

| pT2a | 34 (5.3) | 13 (3.9) | 21 (6.9) | |

| pT2b | 15 (2.3) | 2 (0.6) | 13 (4.3) | |

| pT3a | 136 (21.2) | 33 (9.9) | 103 (33.7) | |

| pT4 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

Values are expressed as medians (interquartile range) unless otherwise specified.

Perioperative Outcomes

Median operative time was similar between PN and RN groups (195 vs 182, P = .5). There was greater estimated blood loss (200 vs 100, P < .001) and utilization of open technique (25.9% vs 9.1%, P < .0001) for PN compared to RN. However, the rate and severity of complications were similar between the 2 groups. A total of 165 (37.8%) and 136 (38.9%) complications occurred in the PN and RN groups, respectively (P = .3). Clavien grade I–II complications occurred in 116 (26.5%) of PN and 103 (29.4%) of RN patients. Clavien grade III–IV complications occurred in 49 (11.2%) of PN and 33 (9.4%) of RN patients. No patients in either group died in the perioperative period (Clavien grade V). Overall rate of urologic complications was not significantly different between the PN and RN groups (43% vs 38%, P = .4). Individual complication varied by surgical approach. Patients undergoing PN had higher rates of bleeding (7.3% vs 1.5%, P = .03) and urine leak (10.3% vs 0.7%, P = .004), whereas RN patients had higher rates of urinary retention (28% vs 9.7%, P = .01), wound infection (13.2% vs 4.2%, P = .007), and wound dehiscence (3.7% vs 0%, P = .002). There was also a trend for increased arteriovenous malformation or pseudoaneurysm (3% vs 0%, P = .7) in the PN group; however, this difference was not statistically significant. There was no difference in the rate of abscess (1.2% vs 0%, P = .5), acute kidney injury (3% vs 4.4%, P = .6), anemia (3.6% vs 2.9%, P = 1), clot retention (0.6% vs 0.1%, P = 1), epididymitis or orchitis (1.2% vs 2.2%, P = .7), hernia (3.6% vs 2.9%, P = 1), lymphocele (0% vs 0.7%, P = .4), pneumothorax (1.8% vs 2.9%, P = .7), or urinary tract infections (7.9% vs 11.8%, P = .3) among the 2 groups. Rates of nonurologic complications were also similar (57% vs 61.8%, P = .4).

Renal Function Outcomes

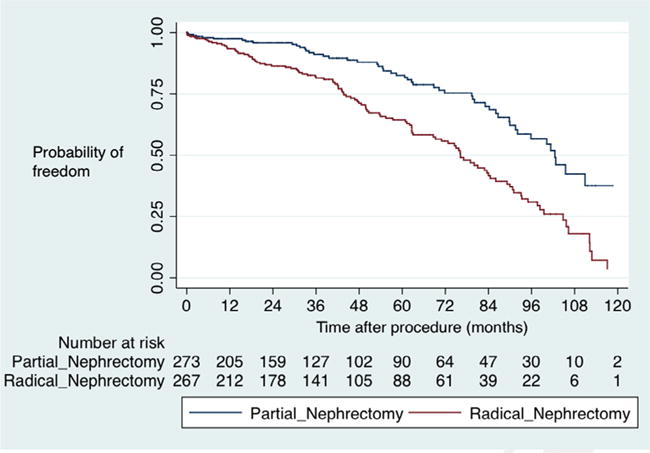

Both cohorts had similar eGFR at baseline (65.7 vs 64.7, P = .3). Postoperative renal function outcomes favored PN (Table 2). PN had higher eGFR at last follow-up (59.1 mL/min/1.73 m2 vs 42.5 mL/min/1.73 m2, P < .001), percent change in eGFR from baseline (6.4% vs 19.7%, P < .001), and greater probability of freedom from eGFR<45 mL/min/1.73 m2 (83.7% vs 64.0%, P < .001) (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Perioperative and postoperative outcomes of patients undergoing partial nephrectomy and radical nephrectomy

| Partial nephrectomy (n = 437) | Radical nephrectomy (n = 350) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time (min) | 195 (150–249) | 182 (150–218) | .051 |

| Approach, n (%) | |||

| Minimally invasive | 324 (74.1) | 318 (90.9) | <.0001 |

| Open | 113 (25.9) | 32 (9.1) | |

| EBL (mL) | 200 (100–300) | 100 (50–200) | <.0001 |

| Postoperative complication, n (%) | 165 (37.8) | 136 (38.9) | 0.3 |

| Clavien I–II | 116 (26.5) | 103 (29.4) | |

| Clavien III–IV | 49 (11.2) | 33 (9.4) | |

| Clavien V | 0 | 0 | |

| Type of complication, n (%) | 0.4 | ||

| Urologic | 71 (43) | 52 (38.2) | |

| Nonurologic | 94 (57) | 84 (61.8) | |

| Urology complications | |||

| AVM or pseudoaneurysm | 5 (3.0) | 0 | .07 |

| Abscess | 2 (1.2) | 0 | 0.5 |

| AKI | 5 (3.0) | 6 (4.4) | 0.6 |

| Anemia | 6 (3.6) | 4 (2.9) | 1 |

| Bleeding | 12 (7.3) | 2 (1.5) | .03 |

| Clot retention | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) | 1 |

| Epididymitis or orchitis | 2 (1.2) | 3 (2.2) | 0.7 |

| Hernia | 6 (3.6) | 4 (2.9) | 1 |

| Lymphocele | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0.4 |

| Pneumothorax | 3 (1.8) | 4 (2.9) | 0.7 |

| UTI | 13 (7.9) | 16 (11.8) | 0.3 |

| Urinary retention | 16 (9.7) | 28 (20.6) | .01 |

| Urine leak | 17 (10.3) | 1 (0.7) | .0004 |

| Wound dehiscence | 0 | 5 (3.7) | .002 |

| Wound infection | 7 (4.2) | 18 (13.2) | .007 |

| Preoperative eGFR | 65.7 (52.2–80.7) | 64.7 (52.8–74.2) | 0.3 |

| Last postoperative eGFR | 59.1 (42.7–72.2) | 42.5 (32.6–54.7) | <.0001 |

| Change in eGFR from baseline | 6.4 (−2.2 to 17.4) | 19.7 (10.0–29.4) | <.001 |

| eGFR < 45, n (%) | 71 (16.3) | 126 (36) | <.001 |

AKI, acute kidney injury; AVM, arteriovenous malformation; EBL, estimated blood loss; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Values are expressed as medians (interquartile range) unless otherwise specified.

Figure 1.

Freedom from eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2.

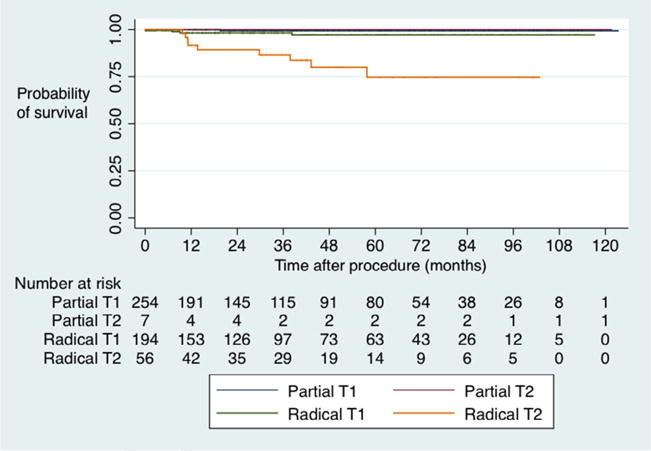

Cancer-specific and Overall Survival Outcomes

In unadjusted survival analysis, CSS favored PN over RN both at 5 years (100% vs 87.5%, P < .001) and at 10 years (100% vs 80.2%, P < .001). Stratified by stage, patients with T2 tumors undergoing RN had the worst CSS (Fig. 2). Interestingly, among patients upstaged to pT3 disease, there was no difference in OS (P = .8) or CSS (P = .5).

Figure 2.

Cancer-specific survival by intervention and clinical stage.

Similarly, OS also favored PN over RN at 5 years (80.2% vs 65.4%, P < .001) and at 10 years (60.6% vs 35.1%, P < .001). However, on multivariable analysis controlling for patient age, tumor diameter, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, and pathologic stage, PN had similar CSS (hazard ratio 1.4, 95% confidence interval [0.3–7.4], P = .7) and OS (hazard ratio 1.0, 95% confidence interval [0.6–1.7], P = .9) compared to RN (Supplementary Table S1).

DISCUSSION

Although PN is currently the preferred surgical treatment for most patients with localized renal masses, the role of PN and RN in elderly patients is not well defined. In this study, we found that elderly patients undergoing PN had better preservation of renal function and similar perioperative morbidity compared to RN, albeit with slightly higher blood loss and rate of open approach in the PN cohort. However, there was no difference in OS or CSS between cohorts. These data may have implications for the choice of therapy in clinical practice.

Recent American Urological Association guidelines state that tumor size, patient comorbidity, and anticipated life expectancy are key factors for selecting treatment approach.11 Our data revealed uneven utilization of treatment in correspondence with these guidelines, revealing an appropriate selection bias. Older patients with more comorbidities and larger, more aggressive tumors were more likely to undergo RN than PN.

A perception in renal surgery is that a “quick” RN may impart a benefit in elderly patients relative to a longer or more complex PN. Our analysis showed similar perioperative outcomes, including operating time. There was a clinically insignificant increase in estimated blood loss and slightly higher rate of open procedures for the PN group. Similar perioperative outcomes between these 2 groups may be attributed to the high volume of our center and kidney surgeons, resulting in relatively faster PN times. Alternatively, as a large volume, academic center, teaching, or resident involvement in laparoscopic RN may skew operative times in the opposite direction. However, operative times were not dramatically different among our large patient population. Importantly, complication rates were also similar among patients undergoing PN and RN. This finding is also supported by a recent study using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, which found that PN had a lower overall complication rate than RN.12

A recent systematic review completed under the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evaluated the comparative efficacy of PN and RN and found similar results—rates of minor and major complications were consistent among surgical approaches.13 The risk of urologic complications and blood transfusion was higher for PN, whereas nonurologic complications (likely related to comorbidities) were higher in RN. Our data did not show a greater incidence of urologic complications in PN. With our population of interest, a more global assessment of the quality of surgical care is necessary. Although many factors contribute to increased surgical morbidity and mortality of the elderly, perioperative complications is a direct cause of poor outcomes in this population.3 In future analysis, a more rigorous assessment of geriatric-specific postoperative complications such as delirium and fall will be included.

The risk of a cardiovascular event leading to death is significantly increased in those with renal dysfunction.14,15 As highlighted in a recent report by Capitanio et al, patients treated with PN have roughly half the risk of developing a new cardiovascular event than their RN counterpart after adjusting for baseline confounders.14 The practical benefit of PN was questioned when a large, multicentered, prospective, randomized trial conducted by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC 30904) indicated that patients undergoing RN had superior OS at 9 years.16 Additionally, patients undergoing PN have improved freedom from eGFR <60, but similar rates of advanced CKD (eGFR <30 and <15) as patients undergoing RN.17 However, patients in EORTC 30904 were, in general, healthy and may not have medical comorbidities that contribute to decreasing eGFR with time. Although the median follow-up for the trial is nearly a decade, this time period may be premature to determine the long-term effects of renal surgery on CKD and subsequent outcomes.

In our analysis, renal functional outcomes were found to be superior in the PN cohort in terms of both change in eGFR and freedom from eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2. Nephron preservation should not be weighted lightly, as it has vast systemic implications. Although the current literature fails to demonstrate a causal relationship between renal surgery and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, a fair amount of circumstantial and retrospective data exist to the merits of PN. The proposed advantages of preserved renal function include avoidance of dialysis, reduced CKD, and reduced death by cardiac events. The risk of a cardiovascular event leading to death is greatly increased in those with renal dysfunction.18 Therefore, it is reasonable to consider that PN can prevent or delay renal, cardiovascular, and other debilitating systemic detriments. Indeed, there is a growing body of literature demonstrating significant differences among patients with surgical CKD in relation to patients with medical CKD.19 This is particularly relevant in the geriatric population, where medical comorbidities may accentuate the effects of surgery. The concept of frailty and functional decline in older adults is closely linked with decreased survival.20 Knowing this, we suspect that nephron-sparing technique holds even greater significance in this vulnerable population.

With regard to survival outcomes, previous studies have yielded conflicting results. Tan and colleagues examined the impact of treatment modality on survival among Medicare beneficiaries with T1a kidney cancer.21 In contrast to our results, they found that PN was associated with a survival benefit that became more apparent with longer follow-up. Whereas our unadjusted data also demonstrated survival benefit, the adjusted data did not; however, our patients were not limited to those with T1a tumors. Because the renal functional benefit of PN is realized over many years, it is possible that not all elderly patients might have a measurable benefit due to their life expectancy.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality report cited above also concluded that CSS was similar between PN and RN, and OSS related to competing risks of health and renal functional outcomes favored PN.13 However, the report cited significant risks of bias in the retrospective literature. In our analysis, PN and RN were shown to have similar outcomes in both CSS and OS after correcting for cofounders. It is unknown if the renal protective benefit of PN would lead to better OS with longer follow-up.

One criticism of these data may be the rate of benign pathology (20%–25%) found at the time of surgery. Our center is increasingly integrating clinical data,22 with renal mass biopsy23 and nuclear imaging data,24 to better determine which patients may be spared from surgical resection. However, for many patients in this 12-year series, these methods were unavailable or infrequently used at the time of their diagnosis.

Limitations of this study include those inherent to a single-institution, retrospective study, as well as limited follow-up. It is also worth noting that 70.9% of the patients had T1 tumors, so findings are mainly driven by patients with smaller cancers. Furthermore, our analysis only included those who underwent surgical management of their renal mass, limiting our ability to assess for alternative management options. Although multiple patient and tumor factors were included in our multivariable analysis, unmeasured confounders and competing risk factors of death were not evaluated for in this analysis.

CONCLUSION

In this series, PN was associated with improved renal function outcomes with no additional morbidity compared to RN. Although no difference was noted between OS and CSS, nephron-sparing technique can have greater implication in the elderly due to reduced baseline kidney function. These data suggest that appropriately selected elderly patients may benefit from PN, and age alone should not be a contraindication to nephron-sparing surgery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: This work is supported by the National Institute on Aging [RFA-AG-15-009], the American Federation for Aging Research, and The John A. Hartford Foundation.

APPENDIX: SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2016.10.047.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

References

- 1.Tsui KH, Shvarts O, Smith RB, Figlin R, de Kernion JB, Belldegrun A. Renal cell carcinoma: prognostic significance of incidentally detected tumors. J Urol. 2000;163:426–430. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)67892-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colby SL, Ortman JM, US Census Bureau, editors. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2015. pp. 25–1143. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turrentine FE, Wang H, Simpson VB, Jones RS. Surgical risk factors, morbidity, and mortality in elderly patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel HD, Kates M, Pierorazio PM, et al. Comorbidities and causes of death in the management of localized T1a kidney cancer. Int J Urol. 2014;21:1086–1092. doi: 10.1111/iju.12527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Touijer K, Jacqmin D, Kavoussi LR, et al. The expanding role of partial nephrectomy: a critical analysis of indications, results, and complications. Eur Urol. 2010;57:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crepel M, Jeldres C, Perrotte P, et al. Nephron-sparing surgery is equally effective to radical nephrectomy for T1BN0M0 renal cell carcinoma: a population-based assessment. Urology. 2010;75:271–275. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.04.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lesage K, Joniau S, Fransis K, Van Poppel H. Comparison between open partial and radical nephrectomy for renal tumours: perioperative outcome and health-related quality of life. Eur Urol. 2007;51:614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowrance WT, Yee DS, Savage C, et al. Complications after radical and partial nephrectomy as a function of age. J Urol. 2010;183:1725–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadjipavlou M, Khan F, Fowler S, et al. Partial vs radical nephrectomy for T1 renal tumours: an analysis from the British Association of Urological Surgeons Nephrectomy Audit. BJU Int. 2016;117:62–71. doi: 10.1111/bju.13114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell SC, Novick AC, Belldegrun A, et al. Guideline for management of the clinical T1 renal mass. J Urol. 2009;182:1271–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel HD, Ball MW, Cohen JE, Kates M, Pierorazio PM, Allaf ME. Morbidity of urologic surgical procedures: an analysis of rates, risk factors, and outcomes. Urology. 2015;85:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierorazio PM, Johnson MH, Patel HD. Management of renal masses and localized renal cancer. J Urol. 2016;196:989–999. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.04.081. Prepared by the JHU Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. HHSA290201200007I. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capitanio U, Terrone C, Antonelli A, et al. Nephron-sparing techniques independently decrease the risk of cardiovascular events relative to radical nephrectomy in patients with a T1a–T1b renal mass and normal preoperative renal function. Eur Urol. 2015;67:683–689. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Poppel H, Da Pozzo L, Albrecht W, et al. A prospective, randomised EORTC intergroup phase 3 study comparing the oncologic outcome of elective nephron-sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy for low-stage renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2011;59:543–552. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scosyrev E, Messing EM, Sylvester R, Campbell S, Van Poppel H. Renal function after nephron-sparing surgery versus radical nephrectomy: results from EORTC randomized trial 30904. Eur Urol. 2014;65:372–377. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demirjian S, Lane BR, Derweesh IH, Takagi T, Fergany A, Campbell SC. Chronic kidney disease due to surgical removal of nephrons: relative rates of progression and survival. J Urol. 2014;192:1057–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane BR, Campbell SC, Demirjian S, Fergany AF. Surgically induced chronic kidney disease may be associated with a lower risk of progression and mortality than medical chronic kidney disease. J Urol. 2013;189:1649–1655. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marengoni A, von Strauss E, Rizzuto D, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. The impact of chronic multimorbidity and disability on functional decline and survival in elderly persons. A community-based, longitudinal study. J Intern Med. 2009;265:288–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan HJ, Norton EC, Ye ZJ, Hafez KS, Gore JL, Miller DC. Long-term survival following partial vs radical nephrectomy among older patients with early-stage kidney cancer. JAMA. 2012;307:1629–1635. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ball MW, Gorin MA, Bhayani SB, et al. Preoperative predictors of malignancy and unfavorable pathology for clinical T1a tumors treated with partial nephrectomy: a multi-institutional analysis. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:112.e9–112.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahbar H, Bhayani S, Stifelman M, et al. Evaluation of renal mass biopsy risk stratification algorithm for robotic partial nephrectomy—could a biopsy have guided management? J Urol. 2014;192:1337–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorin MA, Rowe SP, Baras AS, et al. Prospective evaluation of (99m)Tc-sestamibi SPECT/CT for the diagnosis of renal oncocytomas and hybrid oncocytic/chromophobe tumors. Eur Urol. 2016;69:413–416. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.