Abstract

Living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) is the optimal treatment for end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). The evaluation process for a kidney transplant is complex, time consuming, and burdensome to the ESKD patient. Also, race disparities exist in rates of transplant evaluation completion, transplantation, and LDKT. In December 2012 our transplant center implemented a streamlined, one-day evaluation process, dubbed Kidney Transplant Fast Track (KTFT). This paper describes the protocol of a two-part study to evaluate the effectiveness of KTFT at increasing transplant rates (compared to historical controls) and the TALK intervention (Talking About Live Kidney Donation) at increasing LDKT during KTFT. All participants will receive the KTFT evaluation as part of their usual care. Participants will be randomly assigned to TALK versus no-TALK conditions. Patients will undergo interviews at pre-transplant work-up and transplant evaluation. Transplant status will be tracked via medical records. Our aims are to: (1) test the efficacy and cost effectiveness of the KTFT in reducing time to complete kidney transplant evaluation, and increasing kidney transplant rates relative to standard evaluation practices; (2) test whether TALK increases rates of LDKT during KTFT; and (3) determine whether engaging in a streamlined and coordinated-care evaluation experience within the transplant center reduces negative perceptions of the healthcare system. The results of this two-pronged approach will help pave the way for other transplant centers to implement a fast-track system at their sites, improve quality of care by transplanting a larger number of vulnerable patients, and address stark race/ethnic disparities in rates of LDKT.

Introduction

Kidney transplantation (KT) is the optimal treatment for end-stage renal disease. It reduces mortality, improves quality of life, and is less costly than dialysis.(1–6) Further, living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) is a better option than deceased donor kidney transplantation (DDKT): patients who can identify a living donor will get a transplant sooner than those awaiting DDKT(7, 8), and LDKT also yields better outcomes in terms of cost effectiveness, morbidity, and long-term survival.(9) To be listed for transplant, patients must be referred and then complete the transplant evaluation process.(10) Our previous NIDDK-funded (11–13) research indicated that African Americans (AA) took significantly longer to complete this process. Other research has reported similar results in other vulnerable groups (e.g., Hispanic/Latino, Native Americans, persons with low income).(14–18)

The KT evaluation process is complex, requiring that a patient attend a full day evaluation at the transplant center, and completes at least 15 clinical tests (e.g., blood work, cardiac checks, pap smear, colonoscopy), to be presented to the transplant team before listing a patient. Typically, it is the patient’s responsibility to schedule and complete these tests and to ensure that providers forward the results to the transplant team. This process requires substantial oversight and follow-up and can be confusing for patients. In contrast, evaluations for other organ transplants are typically completed sooner (≤ 3 days) and are facilitated directly by the transplant team. Adapting this approach to KT may help reduce the time to complete an evaluation, allowing more individuals from vulnerable populations to be listed and obtain transplants.(19) Thus, we created the Kidney Transplant Fast Track (KTFT) protocol at our transplant center, a one-day streamlined evaluation process in which all pre-transplant testing occurs at the transplant center. Although similar programs exist at other transplant centers, to our knowledge, none of those centers have studied their effects prospectively.

The evaluation period also provides an opportunity to tackle the other major factor contributing to race disparities in KT, lower rates of LDKT. The Talking About Live Kidney Donation (TALK) intervention is a validated, culturally sensitive program to improve patients’ and families’ consideration of LDKT.(20–22) The educational component of the TALK intervention may increase LDKT in vulnerable group members undergoing transplant evaluation. However, this intervention has never been tested in the context of an expedited transplant evaluation program.

This paper describes the protocol of a two-part study to evaluate the potential for KTFT to increase transplant rates and for the TALK intervention to increase LDKT. Our aims are to: (1) test the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of KTFT in reducing time to complete KT evaluation, and increasing KT rates; (2) using an RCT, test the effectiveness of the TALK intervention in increasing rates of LDKT during KTFT; and, (3) determine whether engaging in a comprehensive, streamlined, and coordinated-care evaluation experience within the transplant center reduces negative perceptions of the healthcare system.

Methods

Overview

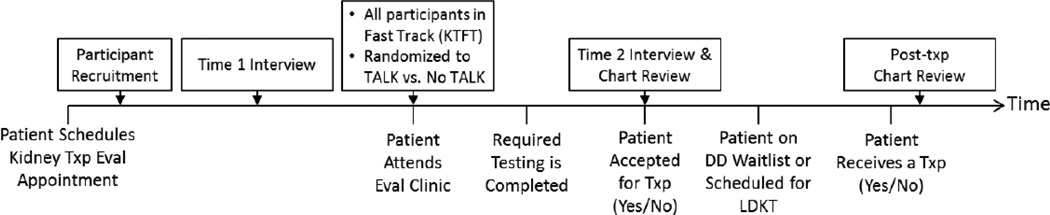

Ours is a two-part study which includes a quasi-experimental design to test the effectiveness of the KTFT, and a randomized controlled trial of the TALK intervention (see Figure 1). We will recruit ESKD patients who schedule an evaluation appointment for KT at the Starzl Transplant Institute at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). The protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. We will obtain written informed consent from all participants. After recruitment (but before their first clinic appointment), participants will be randomly assigned to the TALK or no TALK condition and complete a telephone interview. Because our clinic already fully implemented the KTFT, all participants undergo this process as part of their usual care. Using a quasi-experimental design, we will compare these patients to matched historical controls from our previous study.(23) At the evaluation appointment participants assigned to the TALK condition will receive the TALK intervention. We will follow patients via medical record to determine when they complete testing for evaluation and whether they are accepted or found ineligible for transplant. We will then complete a follow-up interview with all participants.

Figure 1.

Diagram of Pathway to Receiving a Transplant, Intervention and Interview Time Points

Target Populations

Our study focuses on patients undergoing kidney transplant evaluation. We will recruit patients who schedule a kidney transplant evaluation appointment at any of the 3 sites included in our study. Male and female, English speaking, ESKD patients aged 18 and over, who have not previously received a kidney transplant and have not been accepted for kidney transplantation in another center, will be eligible for enrollment. Patients with prior kidney transplants, those who are already on the UNOS waiting list through another center, or those that participated in our previous study(23) will be excluded to eliminate the possibility that past experiences would affect their current treatment decisions.(24)

The historical control group will be based on the 1,727 patients who attended transplant clinics from our previous study. Of them, 1,149 were eligible, gave consent, and completed the same T1 interview that will be used in the current study. Excluding 15% lost to follow-up patients, 793 made it to the T2 interview. And of those, 164 (21%) were transplanted. During the 33 month recruitment period, 640/1149 (55.7%) individuals were accepted or rejected for kidney transplant (with others being accepted or rejected throughout the remaining study period).

Screening and Recruitment

Participants will be recruited using a standard mailed opt-out procedure before their initial transplant clinic appointment. With the assistance of the kidney transplant clinic scheduler, a letter describing the study and signed by the kidney transplant program director at Starzl will be mailed to all patients who have scheduled their initial evaluation clinic appointment. The letter will provide potential participants with instructions to call or email the research team if they do not wish to participate in the study. If a potential participant does not opt-out of the study within one week of mailing, a research staff member will screen his or her UPMC electronic medical record to determine eligibility. Eligible participants will then be contacted via telephone by a study staff member. If a patient is interested in participating in the study, the study staff member screen for eligibility criteria (described above), explain the study, answer any questions, and obtain verbal consent for participation. Participants who provide verbal consent will also be asked to schedule a time over the next 1–2 weeks, prior to the transplant evaluation appointment, to complete a baseline telephone interview.

KTFT Intervention and Adaptation

After extensive discussion and review with administration, transplant physicians, nurse coordinators, and administrative support, our KT program instituted a streamlined evaluation approach, Kidney Transplant Fast Track (KTFT) in December 2012. This approach involves completion of most or all testing on the same day that patients arrive for their first pre-transplant clinic appointment, rather than providing patients with a list of tests to be completed on their own with their referring physician. If patients are unable to complete all testing on the same day as their evaluation, a transplant clinic scheduler or nurse coordinator arranges appointment times and preparatory material for all remaining tests to be completed as soon as possible. Although in operation for more than two years, the KTFT approach has not been systematically compared with previous standard care procedures. Thus, we will take advantage of a unique and unusual natural experiment that arose from system-level clinical changes in the way patients are evaluated for kidney transplantation at our center.

Our kidney transplant program serves patients at four different clinic locations throughout Western Pennsylvania (the main transplant center site, and 3 satellite sites). We included only three of these locations (main and 2 satellite sites) in our study because the fourth site is located at a great distance from Pittsburgh and operates independently of the others. We refer to the included study sites as A (main), B and C (satellites). Upon study initiation, the research team shadowed each clinic location and met with clinic staff members including nurse coordinators, administrators, schedulers, and physicians to fully catalogue the individual components of the KTFT protocol. Through this process, the research team grouped the KTFT intervention procedures into 4 categories based on timing: (1) actions occurring prior to the evaluation clinic appointment; (2) actions occurring during the evaluation clinic appointment; (3) actions occurring during the clinic discharge period; and (4) actions occurring after the clinic appointment (Table 1). Together, these categories characterize the full KTFT protocol.

Table 1.

Procedures occurring during the Fast Track Protocol

| Actions Prior To Evaluation Clinic Appointment | Site A | Site B | Site C |

|---|---|---|---|

| The scheduler tells the patient that he/she may be asked to stay and complete some same day tests on the day of the evaluation, they tell them to plan to be at the clinic for the whole day. |

X | X | X |

| The clinic mails a packet to every patient prior to the evaluation. The packet includes letters that (1) tell the patient to expect to complete testing on the day of the evaluation, (2) tell the patient to expect the evaluation to last the whole day, (3) list the standard testing and encourage patients to complete any testing prior to evaluation appointment, (4) encourage patients to complete all testing within UPMC (so that testing may be secured by the clinic scheduler). |

X | X | X |

| Nurse coordinator reviews patient's chart and completed testing. | X | X | |

| Previously completed tests are retrieved if available. | X | X | |

| Nurse coordinator or clinic staff member schedules any remaining tests for the same day as the evaluation, in same office or nearby facility, or close to same day (next day). |

X | X | |

| Nurse coordinator creates an evaluation schedule for each patient depending on which tests they will need on the day of the evaluation. |

X | X | |

| A clinic scheduler calls the patient prior to the clinic date to confirm the evaluation appointment and scheduled testing. |

X | X | |

| If a patient does not show up to the scheduled evaluation appointment, a nurse coordinator or clinic staff calls first thing in the morning to cancel any scheduled testing. |

X | X | |

| Actions During Evaluation Clinic Appointment | |||

| Patients are pre-screened at the beginning of the visit and patients with contraindications for transplant are sent home, and have their evaluations closed (ex. BMI>40, drug use, poor health, etc.). |

X | X | X |

| Patients participate in an educational class where same-day or close to same-day testing is strongly encouraged. |

X | X | X |

| During the evaluation appointment, clinic staff "ushers" patients to testing locations. | X | X | |

| Walking directions are available to help patients find locations for same day testing facilities (when these facilities are located inside a larger hospital). |

X | ||

| Nurse coordinators retrieve any previously completed testing during the evaluation if it is available (via epic, e-health, care elsewhere or contacting other facilities). |

X | X | X |

| Same day EKG offered | X | X | X |

| Same day Chest X-ray offered | X | X | X |

| Same day Renal Ultrasound offered | X | X | |

| Same day Blood work offered | X | X | X |

| Same day Echocardiogram offered | X | X | |

| Same day Stress test offered | X | X | |

| Same day CT of abdomen offered | X | X | |

| Actions During Evaluation Clinic Discharge | |||

| Nurse coordinator reviews the patient's completed vs. required testing prior to evaluation discharge and creates a tailored evaluation testing plan that is sent home with the patient. |

X | X | X |

| Nurse coordinator communicates to the patient that the patient must complete all remaining testing in order to become listed. |

X | X | X |

| Nurse coordinator encourages patient to schedule remaining testing before leaving the evaluation appointment. |

X | X | X |

| For patients who do not schedule remaining testing before leaving the evaluation appointment, the nurse coordinator instructs them to call the kidney scheduler or coordinator shortly after the evaluation (usually the next day) to schedule any remaining testing. |

X | X | X |

| Nurse coordinator encourages the patient to complete any remaining same day testing before leaving the evaluation location. |

X | X | X |

| Nurse coordinator communicates to patient that completing any remaining testing the same day as the evaluation may help them become listed more quickly. |

X | X | X |

| Actions After Evaluation Clinic Appointment | |||

| Nurse coordinator communicates to the patient that all testing must be completed within 90 days or their evaluation will be closed. |

X | X | X |

| A letter listing the patient's remaining required testing is mailed to the patient, their PCP and their dialysis center. |

X | X | X |

| Nurse coordinators aggressively follow up with patients to retrieve any remaining testing. |

X | X | X |

| Nurse coordinators offer to help schedule any remaining testing after the evaluation (and can help patients with obtaining earlier appointment dates). |

X | X | X |

| Patients call in to the clinic scheduler to schedule any remaining testing | X | X | X |

During our observation and discussion period, we determined that the transplant team implemented the KTFT protocol differently at each site due to various structural and financial barriers. Namely, Sites B and C offer patients all actions that make up the full KTFT protocol, but Site A offers an abbreviated version of the KTFT protocol (Table 1). Specifically, Site A conducts the following procedures in lieu of the KTFT protocol (that was implemented in Site B and C): (1) standardized communication protocol with patients regarding evaluation procedures; (2) streamlined testing and scheduling; and (3) modified educational materials for patients. Fortuitously, this variation in protocol implementation will allow our research team to examine a dose-response effect of the KTFT protocol. We will be able to test whether full KTFT is essential for the desired outcomes and will add important cost-effectiveness detail to our final analyses.

TALK Education Intervention

The Talking About Live Kidney Donation (TALK) intervention was developed by Boulware and colleagues (20–22) at Johns Hopkins University. Participants in the TALK intervention will receive a culturally sensitive educational booklet and a video administered by the Study Interventionist at their first transplant evaluation clinic appointment. Participants will be given the option of reviewing these materials either on their own or with the interventionist, and either in their homes or at a central location of their choice. The interventionist will also encourage participants to share the materials with their family members or friends.

The material encourages patient and families’ shared and informed consideration of LDKT by providing a booklet that addresses several topics: 1) eligibility for LDKT, 2) the clinical evaluation required for LDKT, 3) the donor selection process, 4) surgical procedures for transplantation and donation, 5) and concerns associated with LDKT (e.g. safety of procedures, concerns about recovery) identified through structured group interviews. The booklet is written at a fourth to sixth grade reading so that it is accessible to persons with limited health literacy. It also provides example ‘model conversations’ which patients and/or family members might use to initiate LDKT discussions, as well as strategies for handling difficult situations (e.g., concerns about pressuring donors during discussions about LDKT (for patients) or methods for approaching potential recipients in need of LDKT (for family members)), a glossary of commonly used medical terms related to LDKT as well as information about publicly available resources for obtaining further information about LDKT.

The video is available via the internet or on DVD, by participant preference. It features testimonials from AA and non-AA patients and families sharing their experiences in considering LDKT, including deliberations about donation and the impact of LDKT on their families. Physicians and social workers describe other factors, such as the need for social support and regular medical follow up for both patients and families that are important for successful long-term outcomes. The video also addresses AAs’ potential mistrust of the transplant process. The video and booklet were both screened by AA and non-AA patients and families prior to final production and their input was incorporated into the final interventions.(21)

The study interventionist will follow-up with all TALK participants via telephone 2 weeks after administering the intervention to encourage the participant to review the materials if they have not done so already and to answer any questions the participant may have.

Random Assignment

Although all participants will undergo the KTFT evaluation, participants will be randomly assigned to the TALK versus No-TALK condition immediately following verbal consent before their first clinic appointment. Transplant clinic staff are blinded to participants’ TALK versus no-TALK condition. Participants are also blinded to condition, until they receive the TALK intervention material. However, all patients are informed about the different conditions of the study during verbal and written consent.

We will use a computer-generated permuted blocked randomization method prepared by our team statistician to avoid bias while ensuring a close balance of the numbers in each group at any time during the trial. We will use random block sizes up to 10, to help avoid the team from being aware of the block size. No-TALK participants will receive usual care and education as they usually would through the Starzl Kidney Transplant Program. Usual transplant education includes general information about transplantation, the evaluation and wait listing process, and general information about LDKT. Participants assigned to the TALK condition will undergo the TALK intervention at their first clinic visit.

Data Collection

We will collect data for this project via two telephone interviews, and medical record review. Telephone interviews will be conducted by the Survey Research Program (SRP) at the University of Pittsburgh Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR). The SRP has extensive experience conducting telephone interviews with a variety of patient populations using a computer-aided telephone interview process in which responses are automatically entered as coded data onto a secure server. Participant contact information and calling times will be forwarded to UCSUR through a secure, password-protected database website and a trained UCSUR interviewer will contact and interview each participant.

The baseline telephone interview (T1) will take place prior to the participant’s evaluation clinic appointment. Telephone interviewers from USCUR and the transplant team will be blinded to participants’ assigned condition (TALK vs. no TALK). T1 data collection includes measures of culturally-related factors, kidney transplant-related knowledge and beliefs, and demographic/health characteristics (Table 2). Total completion time is approximately 35 minutes. The T2 interview will be administered to all participants who took part in the T1 interview, shortly after the participant has completed the transplant evaluation. T2 data collection includes an interview to assess the participant’s perceptions of the quantity and quality of contact with providers from the transplant team, evaluation of the TALK material (for those in the TALK condition), and health related quality of life (QOL) (Table 2). The culturally-related factors will be repeated at this session for all participants to assess and compare changes pre-to-post evaluation. Total completion time for this interview is approximately 30 minutes. T2 data collection will also include a medical record review to obtain kidney transplant-related health information such as the number of potential donors being evaluated, whether there were any medical contraindications for transplant for the recipient and donor, the participant’s status on the waitlist, physical disposition, as well as receipt of transplant, time to transplant, type of transplant received (LD or DD), and any early post-transplant health outcomes for those candidates that were accepted for kidney transplant.

Table 2.

Outcomes and predictors in KTFT-TALK protocol

| Study Variables | Description | When Assessed |

Supporting References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | |||

| Receipt of KT & type of transplant | Medical record abstraction:

|

T2 and post-KT |

-- |

| Time to complete evaluation | Medical record abstraction | T2 | -- |

| Kidney transplant decision-making | 7-item measure to assess type of transplant preference |

T1, T2 | (11, 12, 25– 27) |

| Booklet and video helpfulness | Perceptions of video and booklet quality and helpfulness (for TALK participants only) |

T2 | (20, 21) |

| QOL | KDQOL-SF | T2 | (28) |

| Culturally-related factors | |||

| Medical mistrust/Trust in physician |

18 items adapted from LaVeist’s Medical Mistrust Index (MMI) |

T1, T2 | (29–31) |

| Discrimination experience | 7-item measure to assess perceived discrimination in health care |

T1, T2 | (32–34) |

| Perceived Racism | 4-items based on the work of LaVeist | T1, T2 | (11, 12, 27, 29, 31) |

| Religious Beliefs | Religious affiliation and level of importance of religious beliefs Revised subscale of the Organ Donation Attitude Survey (ODAS) |

T1 | (11, 12, 27, 35) |

| Family loyalty | 16-item Bardis Familism scale. | T1 | (11, 12, 36, 37) |

| Transplant-Related Beliefs | |||

| Kidney transplant knowledge | Items adapted from the Kidney Transplant Knowledge Survey and the Kidney Transplant Questionnaire |

T1 | (11, 12, 25– 27) (38) |

| Learning activities | How patients first heard about kidney transplant Who first told them that they can get a kidney transplant 10 items adapted from the KTQ |

T1 | (11, 12, 25– 27) |

| Kidney transplant concerns | 30 items adapted from the KTQ | T1 | (11, 12, 25– 27) |

| Kidney transplant attitudes | 28 items adapted from Pradel and the KTQ | T1 | (8, 11, 12, 25– 27) |

| Perceptions of clinical encounter | Client Satisfaction Questionnaire | T2 | (39, 40) |

| Demographic/Health Characteristics | |||

| Demographic characteristics | Items include:

|

T1 | (41) |

| ESKD Health History | 12-items adapted from the KTQ to assess self-reported ESKD health history |

T1 | (11, 12, 25– 27) |

| Pre-transplant Health Status | Medical record abstraction:

|

T1 | (42) |

| Donor characteristics | Medical record abstraction:

|

T2 | (42, 43) |

Participant Reimbursement and Retention Methods

Participants will receive a $40 payment after completing each interview. Payments will be administrated either through the mail or in person at the transplant clinic, per participant preference. Participant tracking and follow-up procedures that focus on the monitoring and observation of every recruited participant will be used to maintain high retention and response rates. The first step in this process will be to maintain an online recruitment database shared by the core research team and the SRP at UCSUR that includes real-time communication of all newly-recruited participants and the status and outcome of each participant interview. Another internal database will be maintained by the Project Coordinator, Research Assistant, and Database Manager. This database will include participant information (e.g., contact information), recruitment dates, interview dates, completion dates, and payment dates. It will be used to create weekly reports of recruitment tallies, and to keep track of ineligible patients, refusals, and follow-up phone call lists.

The second step in this process will be a weekly meeting of the core research team including the Principal Investigator, Project Coordinator, Study Interventionist and Research Assistant to review clinic totals, numbers recruited and refused, reasons for refusal and detailed discussions to determine ways to address similar refusals in the future. These weekly meetings also will be devoted to discussing hard to reach participants, and determining alternate ways to reach the participant. Although hard to reach participants are expected to be minimal based on our previous work, a careful, detailed approach will be used to ensure that participants complete the interview, while at the same time balancing the desire to refrain from any undue burden or feelings of harassment on the participant. Alternate interview methods will be explored, including in-person interviews during other clinic appointments, alternate call locations, or alternate methods of interview completion (e.g., mailed questionnaires). For each hard to reach participant, a detailed plan of follow-up will be determined and a follow-up date is assigned to ensure that the study team is aware of their status.

Our final method of participant recruitment and retention will involve communication with participants in the study via a bi-annual newsletter. These newsletters will include a brief summary of study progress, a description of the study team, a research staff spotlight, special interest pieces regarding national, international, and local kidney events, web resources for kidney transplant recipients, donors, and their caregivers, and a kidney-friendly recipe. The newsletters will be created by the core research staff and produced by the University of Pittsburgh, the content will be approved by the IRB, and a professional-grade newsletter will be mailed to each participant. The newsletters were highly successful in maintaining participant interest and engagement with our previous projects, and also helped to identify incorrect or outdated mailing addresses for participants.

Analysis of Specific Aims

Our main analysis will be intent-to-treat. We will describe baseline demographic and health-related characteristics for patients in each racial group. Attrition rates and reasons will also be recorded. Patients who do not show up for the scheduled clinical appointments or report that they never reviewed the TALK booklet will be deemed nonadherent to the intervention.

For Aim 1 (test the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of KTFT in reducing time to complete KT evaluation, and increasing KT rates), we will use a survival regression model (e.g., Cox proportional hazards model) to examine the distributions of time from enrollment to complete transplant evaluation and receipt of kidney transplant for KTFT versus historical control groups, and to compare the rates between the two groups. A weighted survival regression model or a survival regression model with multiple imputed data may be necessary depending on the percent and type of missing data. We will calculate and compare the rates of acceptance for KT between the historical control and KTFT groups. Poisson regression model will be used to adjust for any possible confounders.

For Aim 2 (test the effectiveness of the TALK intervention in increasing rates of LDKT during KTFT), we will compare the outcomes between TALK and no-TALK by focusing on the intent-to-treat analysis. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test will be used to compare the proportions of LDKT between the two groups. We will perform a post hoc analysis for participants in the TALK condition to compare those who reviewed the TALK materials independently to those who did so with the interventionist.

For Aim 3 (determine whether engaging in a streamlined and coordinated-care evaluation experience within the transplant center reduces negative perceptions of the healthcare system), we will examine the change in negative perceptions of the healthcare system (i.e., medical mistrust, perceived discrimination and racism) before and after the KTFT intervention by conducting McNemar’s test to examine whether the change is significant, and use a logistic regression model to adjust for potential confounders. We will also conduct a logistic regression model to test whether the proportion of participants with negative perceptions of the healthcare system in KTFT is different from the proportion in the historical control group adjusting for the proportion before KTFT intervention and potential confounding variables. For the possible impact of missing data, we will use weighted generalized estimate equations (GEE) for logistic models or GEE for logistic models with multiple imputed data (44–46).

Power and Sample Size Estimates

Based on our previous work and UPMC data over the past 5 years, the KTFT group is estimated to include 2093 patient who attend transplant clinic. Of those, 1611 are estimated to be eligible, and 1289 (conservative 20% refusal rate) are estimated to give consent, be randomized to an intervention or control group, and complete the T1 interview. Of those who complete the T1 interview, using a 15% loss-to-follow up rate, we estimate that 1096 will complete the T2 interview. Among the T2 completers, at least 230 are expected to be transplanted (21%) by the end of the study period (based on our previous study). Thus, based on these rates, we will have 80% power to detect a hazard ratio of 1.22 between the two groups (Specific Aim 1: test the efficacy and cost effectiveness of the KTFT in reducing time to complete kidney transplant evaluation, and increasing kidney transplant rates relative to standard evaluation practices). A log-rank model of a two-sided test is assumed. The type I error rate will be set to 0.05. For Specific Aim 2 (Using an RCT, test the effectiveness of the TALK intervention in increasing rates of LDKT during KTFT), based on the intent-to-treat analysis, we will have 80% power to detect a 5% increase in rates of LDKT for those in the TALK intervention. For Specific Aim 3 (determine whether engaging in a streamlined and coordinated-care evaluation experience within the transplant center reduces negative perceptions of the healthcare system), based on the historical controls, we estimate mean (SD) = 2.6 (0.5) for the medical trust measure. We will have 80% power to detect a 0.1 unit difference between the KTFT patients and the controls and to detect a 0.0425 unit difference before and after intervention among KTFT patients. Based on the historical controls, we will have 27.9% AA patients and 50.8% of them reported discrimination in our previous work. Therefore, we will have 80% power to detect a 10.7% decreasing rate of discrimination for the KTFT patients compared to the controls and to detect a 3.8% difference in rate of discrimination before and after intervention among KTFT patients. For all calculations, two-sided tests and Type I error rate of 0.05 are assumed.

Cost-Effectiveness Analyses for Aims 1 and 2

Given the potential for added costs of the KTFT intervention relative to usual care, we will need to consider whether the revised clinical approach appears cost-effective by comparing the costs and benefits for each intervention (Aim 1). To evaluate the cost-effectiveness analysis of KTFT+TALK, KTFT alone, and standard care, we will collect costs incurred by the program (e.g., TALK intervention staff, material costs, additional transplant clinic staff costs), as well as preference-based quality of life measures, measures of kidney function, and kidney transplant-specific outcomes (e.g., time to complete evaluation, number of kidney transplants completed, number of LDKT or DDKT).

We will separately account for program-related costs essential to any clinic-based implementation of these interventions and research-related costs specific to this project (see Table 3). Personnel costs will be estimated based on mean salary information and reported time costs. For example, clinic staff will prospectively track time spent performing various duties associated with coordinating and managing patients through the evaluation process, including telephone and email communications with patient participants, answering participant questions, scheduling appointments). Schedulers will log dates, times, and durations of contact with participants and the reasons for the contact; they will also track meetings and contacts with research staff. TALK interventionist salary and materials will also be included in the increased clinical costs of the RCT intervention.

Table 3.

Costs to be included in the cost-effectiveness analysis

| Clinical Costs | Research Costs |

|---|---|

| Staffing - Clinic Schedulers, standard care staff, TALK interventionist |

Staffing: Project coordinator, research assistants, statisticians, researchers |

| Lab work, blood tests | Data management |

| Evaluation and testing (clinical evaluations) | Participant payments |

| Direct care costs (dialysis- and KT-related) | Participant newsletters |

| Interventionist training | Dissemination at scientific meetings |

In addition to clinical and staff costs, we will also estimate patient time to complete the numerous tests comprising the evaluation process. These and other similar time costs associated with seeking and receiving care will be treated as true costs of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio and will appear in the numerator as recommended,(47) while productivity losses will be reflected in quality of life estimates and therefore will appear in the denominator. These base case values for time costs will be rough approximations and consequently will be key parameters to test in sensitivity analyses.

Discussion

Medical factors alone do not explain racial disparities in kidney transplantation, intensifying the need for interventions that address non-medical factors. The KTFT-TALK study uses two separate, but complementary approaches to address the two most critical factors leading to race disparities in kidney transplantation rates: longer time to complete kidney transplant evaluation and lower rates of LDKT among minorities. The KTFT intervention applies system level changes to relieve non-medical barriers to kidney transplantation. By decreasing the complexity and logistical challenges related to completing the kidney transplant evaluation, KTFT aims to increase the number of vulnerable group members who complete the evaluation process which could increase their access to kidney transplant. Further, the TALK intervention is a validated, culturally-tailored tool based on focus groups, patient interviews, and previous validation studies. Incorporating the educational component of the TALK intervention may increase the likelihood that more vulnerable patients will explore LDKT with their loved ones, thereby increasing the number of vulnerable patients that ultimately pursue LDKT. Although each intervention could individually increase rates of kidney transplantation and reduce disparities, we believe that the two interventions together should yield greater benefit to vulnerable groups. The results of this two-pronged approach will help pave the way for other transplant centers to implement a fast-track system at their sites, improve quality of care by transplanting a larger number of vulnerable patients, and may help address stark race/ethnic disparities in rates of LDKT.

Acknowledgments

The project described is supported by Award Number 1R01DK101715-01A1 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. The NIDDK had no involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of this report; or in the decision to submit this article for publication

We thank the following individuals for their contributions to the project: Allison Asbury, Angelina Biziaev, Antoinette Carroll, Lydia Dandapat, Lynette Defilippo, Erin Hansen, Natalie Iacovoni, Jacqueline Miller.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Evans R, Manninen D, Garrison LJ, Hart L, Blagg C, Gutman R, et al. The quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 1985;312(9):553–559. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198502283120905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunsicker L. A survival advantage for renal transplantation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341:1762–1763. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasiske BL, Snyder JJ, Matas AJ, Ellison MD, Gill JS, Kausz AT. Preemptive kidney transplantation: The advantage and the advantaged. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2002;13(5):1358–1364. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000013295.11876.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LYC, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341(23):1725–1730. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eggers P. Effect of transplantation on the Medicare end-stage renal disease program. New England Journal of Medicine. 1988;318(4):223–229. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198801283180406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Port F, Wolfe R, Mauger E, Berling D, Jiang K. Comparison of survival probabilities for dialysis patients vs. cadaveric renal transplant recipients. JAMA. 1993;270(11):1339–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schweitzer EJ, Yoon S, Hart J, Anderson L, Barnes R, Evans D, et al. Increased living donor volunteer rates with a formal recipient family education program. American Journal of Kidney Disease. 1997;29(5):739–745. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pradel FG, Limcangco MR, Mullins CD, Bartlett ST. Patients' attitudes about living donor transplantation and living donor nephrectomy. American Journal of Kidney Disease. 2003a;41(4):849–858. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ojo AO, Port FK, Mauger EA, Wolfe RA, Leichtman A. Relative impact of donor type on renal allograft survival in black and white recipients. American Journal of Kidney Disease. 1995;25(4):623–628. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garg PP, Frick KD, Diener-West M, Powe NR. Effect of the ownership of dialysis facilities on patients' survival and referral for transplantation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341(22):1653–1660. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911253412205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myaskovsky L, Doebler D, Posluszny D, Dew M, Unruh M, Fried L, et al. Perceived discrimination predicts longer time to be accepted for kidney transplant. Transplantation, “Editor’s Pick”. 2012;93(4):423–429. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318241d0cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myaskovsky L, Pleis J, Ramkumar M, Mittalhenkle A, Langone A, Thomas C. Preliminary Results from the National VA Kidney Transplant Study. Seattle, WA: American Transplant Congress; 2013. Has the VA Found a Way to Reduce Racial Disparities in Kidney Transplant Evaluation? [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myaskovsky L, Switzer G, Dew M, Shapiro R, Unruh M, Ford AF, et al. Understanding Race and Culture in Living Donor Kidney Transplantation. Starzl Transplant Institute, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center: NIDDK; 2009–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health and Human Services HRaSA, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation, editor. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. OPTN / SRTR 2011 Annual Data Report. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sequist TD, Narva AS, Stiles SK, Karp SK, Cass A, Ayanian JZ. Access to renal transplantation among American Indians and Hispanics. American Journal of Kidney Disease. 2004;44(2):344–352. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander CG, Sehgal AR. Barriers to cadaveric renal transplantation among blacks, women and the poor. The Journal of American Medical Association. 1998;280(13):1148–1152. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young CJ, Gaston RS. Understanding the influence of ethnicity on renal allograft survival. American Journal of Transplantation. 2005;5(11):2603–2604. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Formica RN, Barrantes F, Asch WS, Bia MJ, Coca S, Kalyesubula R, et al. A one-day centralized work-up for kidney transplant recipient candidates: A quality improvement report. American Journak of Kidney Disease. 2012;60(2):288–294. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boulware L, Hill-Briggs F, Kraus E, Melancon J, Falcone B, Ephraim P, et al. Effectiveness of educational and social worker interventions to activate patients' discussion and pursuit of preemptive living donor kidney transplantation: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Kidney Disease. 2013;61(3):476–486. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boulware L, Hill-Briggs F, Kraus E, Melancon J, McGuire R, Bonhage B, et al. Protocol of a randomized controlled trial of culturally sensitive interventions to improve African Americans' and non-African Americans' early, shared, and informed consideration of live kidney transplantation: the Talking About Live Kidney Donation (TALK) Study. BMC Nephrology. 2011;12(34) doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-12-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DePasquale N, Hill-Briggs F, Darrell L, Lewis-Boyer L, Ephraim P, Boulware LE. Feasibility and acceptability of the TALK Social Worker intervention to improve live kidney transplantation. Health and Social Work. 2012;37(4):234–249. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hls034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myaskovsky L, Switzer G, Dew M, Shapiro R, Unruh M, Ford AF, et al. Understanding Race and Culture in Living Donor Kidney Transplantation. Starzl Transplant Institute, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center: NIDDK; 2009–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holley JL, McCauley C, Doherty B, Stackiewicz L, Johnson JP. Patients' views in the choice of renal transplant. Kidney International. 1996;49(2):494–498. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waterman AD, Barrett AC, Stanley SL. Optimal transplant education for recipients to increase pursuit of living donation. Progress in Transplantation. 2008;18(1):55–62. doi: 10.1177/152692480801800111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waterman AD, Stanley SL, Covelli T, Hazel E, Hong BA, Brennan DC. Living donation decision making: Recipients' concerns and educational needs. Progress in Transplantation. 2006;16(1):17–23. doi: 10.1177/152692480601600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myaskovsky L, Pleis J, Dew MA, Switzer GE, Shapiro R. Cultural and psychosocial factors predict racial disparities in kidney transplant evaluation. Baltimore, MD: Academy Health Annual Research Meeting; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, Coons SJ, Amin N, Carter WB. Kidney disease quality of life short form (KDQOL-SF), Version 1.3: A manual for use and scoring. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 1997. p. 7994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boulware LE, Ratner LE, Cooper LA, Sosa JA, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Understanding disparities in donor behavior: Race and gender differences in willingness to donate blood and cadaveric organs. Medical Care. 2002;40(2):85–95. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200202000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaVeist TA, Isaac L, Peterson S, Jackson J, Thomas D. Assessing the validity and reliability of a new measure of distrust of medical care settings: the Medical Mistrust Index. 2003 unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 31.LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African-American and White cardiac patients. Medical Care Research & Review. 2000;57(Suppl 1):146–161. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bird ST, Bogart LM. Perceived race-based and socioeconomic status (SES)-based discrimination in interactions with health care providers. Ethnicity and Disease. 2001;11:554–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bird ST, Bogart LM. Birth control conspiracy beliefs, perceived discrimination, and contraception among African Americans: An exploratory study. Journal of Health Psychology. 2003;8(2):263–276. doi: 10.1177/1359105303008002669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson N. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress, and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rumsey S, Hurford DP, Coles AK. Influence of knowledge and religiousness on attitudes toward organ donation. Transplantation Proceedings. 2003;35(8):2845–2850. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bardis PD. A familism scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1959;21:340–341. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haj-Yahia MM. Attitudes of Arab women toward different patterns of coping with wife abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17:721–745. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murray LR, Conrad NE, Bayley E. Perceptions of kidney transplant by persons with end stage renal disease. Anna Journal. 1999;26(5):479–483. 500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larsen D, Attkinson C, Hargreaves W, Nguyen T. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1979;2:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Attkisson CC, Larsen D, Hargreaves W, LeVois M, Nguyen T, Roberts R, et al. Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 (CSQ-8) In: John Rush A, editor. American Psychiatric Association Task Force for the Handbook of Psychiatric Measures APA. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000. pp. 186–188. Handbook of psychiatric measures. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mays VM, Ponce NA, Washington DL, Cochran SD. Classification of race and ethnicity: Implications for public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 2003;24:83–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jassal SV, Schaubel DE, Fenton SSA. Baseline comorbidity in kidney transplant recipients: A comparison of comorbidity indices. Transplantation. 2005;46(1):136–142. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andreoni KA, Brayman KL, Guidinger MK, Sommers CM, Sung RS. Kidney and Pancreas Transplantation in the United States, 1996–2005. American Journal of Transplantation. 2007;7(5(part 2)):1359–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liange K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal Data Analysis Using Generalized Linear Models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preisser JS, Lohman KK, Rathouz PJ. Performance of Weighted Estimating Equations for Longitudinal Binary Data with Drop-Outs Missing at Random. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21:3035–3054. doi: 10.1002/sim.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robins JM, Rotnitzky A. Semiparametric Efficiency in Multivariate Regression Models with Missing Data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90:581–592. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drummond M, Sculpher M, Torrance G, O’Brien B, Stoddart G. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]