Abstract

Objective

To investigate the psychometric properties of the Clinical Dementia Scale—frontotemporal lobar degeneration (CDR‐FTLD) psychometric properties using Rasch analysis and its sensitivity distinguishing disease progression between FTLD and Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Methods

Of 603 consecutive patients from the National Alzheimer Coordinating Center dataset (FTLD = 350; AD = 253), 120 FTLDs were included in a Rasch analysis to verify CDR‐FTLD psychometric properties; 483 (FTLD = 230; AD = 253) were included to analyse disease progression, with 195 (FTLD = 82; AD = 113) followed‐up (24 months).

Results

The CDR‐FTLD demonstrated good consistency, construct and concurrent validity and correlated well with mini‐mental state examination (MMSE) and disease duration (ps < 0.05). At baseline, FTLD showed greater dementia severity than AD after matched for MMSE and disease duration (p < 0.001). Independent Rasch analyses demonstrated different patterns of progression for FTLD and AD in terms of the domains initially and then subsequently affected with disease progression. At follow‐up, although MMSE showed significant changes (p < 0.05), these were greater on the CDR‐FTLD (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

The CDR‐FTLD satisfactorily measures dementia severity and change in FTLD, distinguishing disease progression between FTLD and AD, with clear implications for care, prognosis and future clinical trials. © 2016 The Authors. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: frontotemporal dementia, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, disease progression, CDR‐FTLD, dementia severity

Introduction

The ability to detect clinical change and attribution of accurate disease severity in frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) is critical for appropriate characterization of research cohorts, prognosis, clinical management and future trials. In the spectrum of clinical disorders due to Alzheimer's disease (AD), the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) (Morris, 1993) is widely regarded as an excellent instrument for rating severity. It is extensively used in drug trials and research studies (Schneider et al., 1997; Rattinger et al., 2015). Specific dementia staging tools in FTLD have not achieved the same kind of consensus. The Frontotemporal Dementia Rating Scale was published in 2010 (Mioshi et al., 2010), demonstrating ability to detect differences in disease progression in frontotemporal dementia (FTD) subtypes and over time. As such, specific tools such as the CDR or Frontotemporal Dementia Rating Scale have demonstrated capability to detect clinical change in different dementia subtypes, but tools that can be reliably applied in both disease groups are limited.

The Clinical Dementia Rating ‐ FTLD scale‐modified (CDR‐FTLD) (Knopman et al., 2008) addresses this issue with the addition of two extra domains, language and behaviour, making it more sensitive to FTLD subtypes, while enhancing description of disease progression in the AD spectrum. It has been shown ability to detect significant change in FTLD‐simulated trials, but its applicability in AD clinical trials has not been tested yet.

Here, we applied Rasch modelling to understand the performance of the CDR‐FTLD. Rasch analysis is a powerful methodology based on item‐response theory, able to investigate items from a scale concomitantly with the performance of patients in these same items, allowing for a direct comparison. Patients and items can be placed in the same continuum, providing great insight into patient performance as well as item difficulty, making this method very appropriate for the validation of disease progression assessment tools.

This study aimed to (i) verify psychometric properties of the CDR‐FTLD via Rasch analysis; (ii) investigate if the CDR‐FTLD could reveal different patterns of disease progression between FTLD and AD dementia; and (3) examine if the CDR‐FTLD could detect longitudinal changes in FTLD and AD dementia.

Methods

Participants

The National Alzheimer Coordinating Center (NACC) developed a database containing extensive clinical information on participants from 34 past and present Alzheimer's Disease Centres (ADCs) in the USA. The NACC database was interrogated on 2 November 2012 to identify patients diagnosed with FTLD or AD according to international criteria. The dataset contained 11 902 patients who were assessed between September 2005 and August 2012. Of those, 603 patients were consecutively included if fulfilling the following criteria: for FTLD (Neary et al., 1998; Gorno‐Tempini et al., 2011; Rascovsky et al., 2011) (n = 350), diagnosis of behavioural variant FTD, primary progressive aphasia semantic variant or non‐fluent variant and no concurrent diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, depression or other psychiatric disease at their first visit, as recorded in the NACC database. Inclusion criteria for dementia due to AD (n = 253) were diagnosis of possible or probable AD (McKhann et al., 2011) and no concurrent diagnosis of vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, depression or other psychiatric disease at the first visit. The NACC protocol and diagnostic criteria have been extensively published.

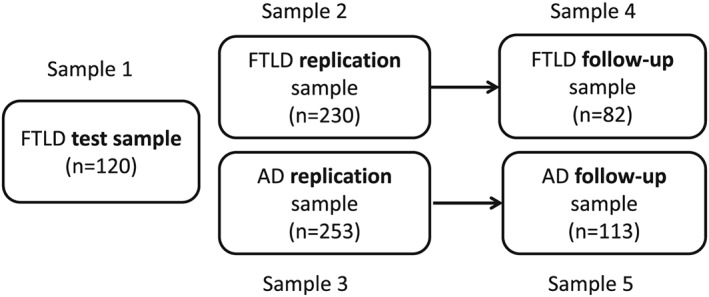

Participants were consecutively included to the FTLD test sample 1 (n = 120), the FTLD replication sample 2 (n = 230) or the AD dementia replication sample 3 (n = 253). Of the replication sample, 82/230 patients with FTLD had 1–3 follow‐up visits; 113/253 patients with AD dementia had follow‐up data (Figure 1). Follow‐up data were taken from the visit that took place approximately 24 months following baseline.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of data samples used in the study.

Instruments

Clinical Dementia Rating Scale for FTLD

The CDR‐FTLD is an extended version of the CDR and includes two additional domains: language and behaviour. It has shown to be more sensitive to FTLD than the original CDR, where it was 27% more sensitive in detecting decline over 12 months than the standard CDR score (Knopman et al., 2011). The ‘sum of boxes’, that is, the sum of the individual domain ratings, was used to determine global dementia severity.

General cognitive assessment

The mini‐mental state examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975) was used at baseline and follow‐up visits. The MMSE is a global cognitive assessment widely used in clinical and research dementia centres. The maximum score is 30, with two cut‐offs: 24 (sensitivity 66%, specificity 99%) and 27 (sensitivity 89%, specificity 91%) indicative of cognitive decline yielding different rates of sensitivity and specificity for dementia (O'Bryant et al., 2008).

Statistical analyses

For the investigation of the psychometric properties of the CDR‐FTLD and its validation, a number of metrics were generated by a Rasch analysis (Sample 1) to verify scale item suitability, internal validity and unidimensionality. Rasch analysis allows for the simultaneous verification of the ranking of items in a scale (very difficult to easy), while concomitantly ranking all patients in order of ability (less severe to more severe). Concurrent validity of the scale was checked against the MMSE and length of symptoms, using IBM SPSS 20. The Rasch analyses steps were analysed using Winsteps 7.

For the investigation of the clinical change in FTLD and AD dementia, another two independent Rasch analyses were conducted, one with each diagnostic subgroup (Samples 2 and 3), which revealed the clinical progression of each dementia subtype. Given the violation of normality in the distribution of the CDR‐FTLD scores for both FTLD and AD dementia, non‐parametric repeated measures Wilcoxon test was applied in a subset of patients with follow‐up visits (average 24 months) to verify the ability of the scale in detecting change over time. Non‐parametric Spearman rank correlation analyses were also performed between the CDR‐FTLD and the MMSE and length of symptoms.

Results

Patient characteristics

The FTLD and AD groups were well matched for the time of disease duration (Table 1). The proportion of men and women was dissimilar in both groups, which had also different rates of married people, but mostly had English as their first language. General cognitive scores were matched for FTLD and AD dementia, but severity of dementia was greater for FTLD, as defined by the CDR‐FTLD ‘sum of boxes’.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with FTLD and AD at baseline (Samples 2 and 3). Means; SD in brackets

| FTLD (n = 230) | AD dementia (n = 253) | FTLD versus AD dementia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.9 (8.97) | 74.8 (10.0) | * p < 0.001 |

| Disease duration, years | 4.8 (3.5) | 4.4 (3.0) | * p = 0.169 |

| Male, % | 57.6 | 44.7 | ** p < 0.001 |

| Primary language, English % | 91.7 | 91.7 | **n.s. |

| Marital status, married % | 78.6 | 66.4 | ** p < 0.001 |

| MMSE (max 30) | 21.7 (7.5) | 22.4 (12.5) | * p = 0.089 |

| CDR‐FTLD sum of boxes (max 24) | 8.4 (5.8) | 4.7 (3.7) | * p < 0.001 |

t‐test, p > 0.05.

Chi‐square, p < 0.05.

Validation of the CDR‐FTLD: psychometric properties (Sample 1)

The CDR‐FTLD fulfils all criteria for a valid scale. In regard to items (construct validity), the mean square infit [M = 1.12 (SD = 0.76), Z = −0.5 (SD = 3.9)] and outfit [M = 1.26 (SD = 0.94), Z = 0 (SD = 3.7)] were within the desired values (0.60–1.49; Z = −2 to 2). Unidimensionality was low (29%; desired raw variance would be 50%) because the scale is inherently not unidimensional: It contains different dimensions such as memory, language and behaviour. Test consistency was excellent (0.93), very close to Cronbach's alpha of 0.95 (Bland and Altman, 1997). Item separation was 3.78, which is also very close to the desired value of 3.0 (Linacre and Wright, 2000) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with FTLD and AD at follow‐up (Sample 3). Means; SD in brackets

| FTLD (n = 82) | AD dementia (n = 113) | FTLD versus AD dementia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66.6 (9.4) | 78.3 (9.2) | * p < 0.001 |

| Disease duration, years | 6.8 (3.0) | 7.1 (3.6) | * p = 0.541 |

| Male, % | 57.8 | 55.8 | ** p = 0.772 |

| Primary language, English % | 88.0 | 90.3 | ** p = 0.139 |

| Marital status, married % | 77.1 | 62.8 | ** p < 0.05 |

| MMSE (max 30) | 22.34 (7.2) | 22.5 (5.6) | * p = 0.763 |

| CDR FTLD sum boxes (max 24) | 8.3 (5.3) | 5.0 (3.8) | * p = 0.001 |

| Time between baseline and follow‐up visit (months) | 22.1 (1.0) | 26.3 (11.7) | * p = 0.01 |

t‐test, p > 0.05.

Chi‐square, p < 0.05.

Concurrent validity of the CDR‐FTLD was confirmed by correlations with the MMSE: There was a significant correlation for both patients with FTLD (r = −0.591, p < 0.001) and patients with AD (r = −0.778, p < 0.001). There were also significant correlations between the CDR‐FTLD and length of symptoms for both disease groups (FTLD: r = 0.348, p < 0.001) and AD dementia: r = 0.386, p < 0.001).

Is clinical change in FTLD different from AD?

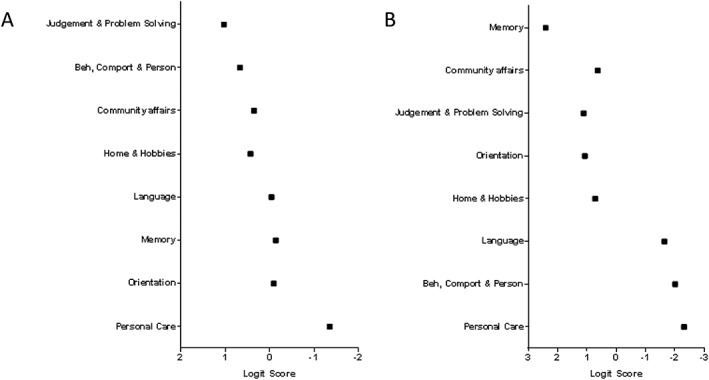

Two independent Rasch analyses (Samples 2 and 3, Figure 1) were conducted for the investigation of clinical change in FTLD and AD using the CDR‐FTLD items. In this analysis, the CDR‐FTLD items were ranked according to the higher assignment of severity exhibited by the patient sample, in this case, each diagnostic group. Figure 2 shows that items with high values are areas affected very early in the disease course, while low value items referring to domains preserved until late in the disease course.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Clinical Dementia Scale—frontotemporal lobar degeneration items for (A) patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration TLD and (B) Alzheimer's disease. Higher logit scores represent greater severity.

As such, the patients with FTLD showed early susceptibility to impairment in judgement and problem solving; next, it was behaviour, comportment and personality and community affairs (Figure 2). Language, memory and orientation were affected later on, and the last domain to be affected was personal care.

For the patients with AD dementia, the expected profile of clinical change was distinct from that of FTLD. Memory was by far the most susceptible domain to be affected, followed by community affairs, judgement and problem solving, orientation and home and hobbies. Language and behaviour were only affected much later in the clinical course, together with personal care.

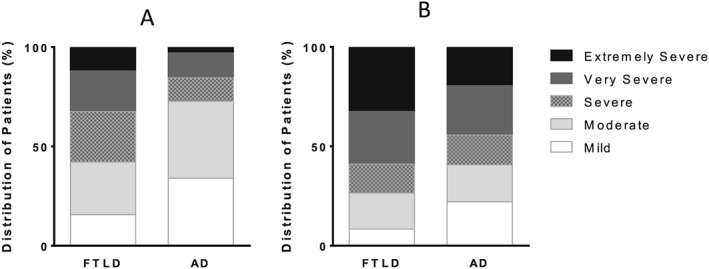

Clinical decline at follow‐up

At baseline, both groups were matched for MMSE scores and length of symptoms, but the CDR‐FTLD scores were clearly distinct (FTLD > AD dementia, p < 0.001). At follow‐up (average 24 months), the CDR‐FTLD sum of boxes (max 24) were significantly lower for both FTLD and AD (both ps < 0.001), reflecting sensitivity to change over time (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(A) Baseline scores; (B) Follow up scores Distribution of CDR‐FTLD sum of boxes severity for FTLD and AD at (A) baseline and (B) follow up.

Discussion

This study systematically investigated patterns of disease progression in FTLD and AD at different stages with a well‐validated staging measure. The results confirm that the CDR‐FTLD provided a clear distinction of clinical changes in the two dementia subtypes, with evident implications for clinical management and future trials of pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions.

The CDR‐FTLD can detect clinical change in FTLD and satisfies required psychometric properties in a number of parameters. Item suitability and item separation were confirmed, with test consistency considered excellent. The measure was strongly associated with global cognitive changes, as measured by the MMSE and length of symptoms, while demonstrating a distinct clinical pattern of progression difference between FTLD and AD dementia. This study went beyond prior analyses (Knopman et al., 2011) and confirmed the utility of the CDR‐FTLD in detecting changes in FTLD and AD dementia over time using Rasch analysis.

The application of Rasch modelling in the process of validating scales is very robust (Bond and Fox, 2015), given its roots in item‐response theory. Item‐response theory models the relationship between abilities measured (e.g. domains in dementia progression) and responses (e.g. patients' performance in the scale) in a mathematical way. In this way, items and respondents are placed in the same dimension and can be compared directly. Traditional approaches in validating health scales tend to rely on classic test theory, which relies on correlations and may be limited in its applicability when tests adopt Likert scales (Churchill, 1979), such as the CDR‐FTLD.

Another advantage of Rasch analysis in validating assessments lies in its strength to determine the most important aspect of test validity, namely construct validity (Wampold, 1998). Construct validity refers to the ability of the scale in measuring things hierarchically, which in the case of the CDR‐FTLD, fits seamlessly in confirming disease progression in FTLD. The validation Rasch results demonstrated that the items of the CDR‐FTLD can effectively order well a patient sample in a disease continuum, from very mild to very severe. Importantly, the replication sample not only confirmed the test applicability in FTLD but also in an independent sample of AD dementia.

By examining the clinical changes in FTLD in a data‐driven approach such as Rasch analysis, our results can guide future interventions to clear targets of disease‐modifying therapies (as well as non‐pharmacological approaches) at different dementia stages.

The limitations in this study include the merging of FTLD subtypes, and for this reason, the differences in variants could not be investigated here. We also lacked autopsy confirmation in both FTLD and AD dementia subgroups, but as with most published studies, we relied on clinical diagnoses made by expert clinicians in the US Alzheimer centres. The strengths of our study include the Rasch analysis methodology for the validation of the CDR‐FTLD in FTLD, large clinical samples, as well as validation in independent cohorts of patients with FTLD and AD, which have also contributed to a greater understanding of the variances in disease progression in the two dementia subtypes.

The understanding of differences in the course of dementia subtypes and validation of appropriate measures not only inform future trials and clinical research, but it can also provide clinical teams with an instrument that can objectively measure relevant health and social care needs at different stages of FTLD.

Key points.

The CDR‐FTLD satisfactorily measures dementia severity and change in FTLD, distinguishing disease progression between FTLD and AD, with clear implications for care, prognosis and future clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

Prof. Mioshi receives research support from the Alzheimer Association (USA, grant NIRP‐12‐258380) and the Alzheimer's Society (UK, grant AS‐SF‐14‐003). Ms Flanagan reports no conflicts of interest. Dr Knopman serves on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals and for the DIAN study, is an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by TauRX Pharmaceuticals, Lilly Pharmaceuticals and the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study and receives research support from the NIH.

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA‐funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI David Teplow, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP) and P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD).

Mioshi, E. , Flanagan, E. , and Knopman, D. (2017) Detecting clinical change with the CDR‐FTLD: differences between FTLD and AD dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, 32: 977–982. doi: 10.1002/gps.4556.

References

- Bland JM, Altman DG. 1997. Cronbach's alpha. BMJ: Brit Med J 314: 572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond T, Fox CM. 2015. Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences. Routledge: Mahwah, New Jersey. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill GA Jr. 1979. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J Marketing Res 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, Mchugh PR. 1975. “Mini‐mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorno‐Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. 2011. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 76: 1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, Kramer JH, Boeve BF, et al. 2008. Development of methodology for conducting clinical trials in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain 131: 2957–2968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, Weintraub S, Pankratz VS. 2011. Language and behavior domains enhance the value of the clinical dementia rating scale. Alzheimers Dement 7: 293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linacre JM, Wright B. 2000. Winsteps. URL: http://www.winsteps.com/index.htm [accessed 2013‐06‐27][WebCite Cache]

- Mckhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. 2011. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 7: 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mioshi E, Hsieh S, Savage S, Hornberger M, Hodges J. 2010. Clinical staging and disease progression in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 74: 1591–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. 1993. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. 1998. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 51: 1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Bryant SE, Humphreys JD, Smith GE, et al. 2008. Detecting dementia with the mini‐mental state examination in highly educated individuals. Arch Neurol 65: 963–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, et al. 2011. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 134: 2456–2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattinger GB, Schwartz S, Mullins CD, et al. 2015. Dementia severity and the longitudinal costs of informal care in the Cache County population. Alzheimers Dement 11: 946–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider LS, Olin JT, Doody RS, et al. 1997. Validity and reliability of the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study—Clinical Global Impression of Change (ADCS‐CGIC). Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disorder 11(Suppl 2): S22–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE 1998. Necessary (but not sufficient) innovation:cComment on Fox and Jones (1998), Koehly and Shivy (1998), and Russell, Kahn, Spoth, and Altmaier (1998).