Abstract

Background

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) are produced by the burning and processing of fuel oils, and have been associated with oxidant stress, insulin resistance and hypertension in adults. Few studies have examined whether adolescents are susceptible to cardiovascular effects of PAHs.

Objective

To study associations of PAH exposure with blood pressure (BP) and brachial artery distensibility (BAD), an early marker of arterial wall stiffness, in young boys attending three schools in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia in varying proximity to an oil refinery.

Methods

Air samples collected from the three schools were analyzed for PAHs. PAH metabolites (total hydroxyphenanthrenes and 1-hydroxypyrene) were measured in urine samples from 184 adolescent males, in whom anthropometrics, heart rate, pulse pressure, brachial artery distensibility and blood pressure were measured. Descriptive, bivariate and multivariable analyses were performed to assess relationships of school location and urinary PAH metabolites with cardiovascular measures.

Results

Total suspended matter was significantly higher (444 ± 143 µg/m3) at the school near the refinery compared to a school located near a ring road (395 ± 65 µg/m3) and a school located away from vehicle traffic (232 ± 137 µg/m3), as were PAHs. Systolic (0.47 SD units, p = 0.006) and diastolic (0.53 SD units, p < 0.001) BP Z-scores were highest at the school near the refinery, with a 4.36-fold increase in prehypertension (p = 0.001), controlling for confounders. No differences in pulse pressure, BAD and heart rate were noted in relationship to school location. Urinary total hydroxyphenanthrenes and 1-hydroxypyrene were not associated with cardiovascular outcomes.

Conclusions

Proximity to an oil refinery in Saudi Arabia is associated with prehypertension and increases in PAH and particulate matter exposures. Further study including insulin resistance measurements, better control for confounding, and longitudinal measurement is indicated.

Keywords: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, Particulate matter, Prehypertension, Brachial artery distensibility, Adolescents

1. Introduction

Outdoor air pollution, a heterogeneous mix of pollutants largely produced through fossil fuel combustion and chemical reactions in the atmosphere (Brook et al., 2004), is well known to contribute to cardiovascular disease (Dockery et al., 1993). Motor vehicles and coal-fired power plants are major sources of these emissions, though oil refineries, aircraft, residential wood burning stoves and natural sources (lightning and wildfires) also are contributors (Bakker et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2010). Associations have been documented to be strongest in particular for two types of air pollution, particulate matter (PM) less than 10 µm in diameter (PM10) and PM less than 2.5 µm in diameter (PM2.5) (Bell et al., 2008; Dominici et al., 2006, 2007a, 2007b). In 2010, 2.1% of the global burden of disease was due to PM-attributable cardiovascular disease (CVD, 53.2 million disability adjusted life years) (Lim et al., 2012).

In an effort to identify sources and guide prevention, studies have rightly endeavored to disaggregate effects of the many chemicals found in air. Among chemical industries, petroleum refineries have been identified as large emitters of pollutants, especially PAHs (Polidori et al., 2010). In particular, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) are known to be potent oxidant stressors (Araujo et al., 2008), which is important because oxidation of lipids contributes to inflammation. PAHs also reduce nitric oxide (Chuang et al., 2012), promoting vasoconstriction, platelet adhesion, and release of inflammatory cytokines (Harrison et al., 2003; Singh and Jialal, 2006). PAHs are also potent aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists, inducting xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes that can augment generation of reactive oxygen species (Korashy and El-Kadi, 2006). Indeed, asphalt workers have been found to have increased fatal ischemic heart disease in association with urinary PAHs (Burstyn et al., 2005), and general population, cross-sectional studies have associated urinary PAHs with CVD (Xu et al., 2010), peripheral arterial disease (Xu et al., 2013), and C-reactive protein (Everett et al., 2010), though another study failed to identify increases in other serum inflammatory markers commonly found in CVD (Clark Iii et al., 2012).

It is well known that children are at particular risk for health effects of air pollutants (Trasande and Thurston, 2005). Children tend to have higher PAH exposure to air, soil and dust than adults because of greater hand-to-mouth activity, time spent close to the ground, and inhalation rates per unit body weight (National Research Council, 1993). In the context of the rising obesity epidemic globally (de Onis et al., 2010), concerns have increased about the action of air pollutants and other environmental stressors on children, especially with increased adipose tissue substrate for oxidant stress. Adding to these concerns, epidemic increases in elevated blood pressure have been documented in the United States (Rosner et al., 2013). Indeed, a study of school-age children identified increases in oxidative stress biomarkers in association with urinary PAHs (Bae et al., 2010).

Jeddah is the second largest city and the most significant commercial center in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The growth of the city over the last thirty years has been rapid, (Saudi Network, 2008) without awareness of health consequences and regulations to limit environmental degradation. In Jeddah, stationary sources of air pollutants include an oil refinery, a desalinization plant, a power generation plant and several manufacturing industries. Many of the industrial facilities, for example, the Jeddah oil refinery, were originally built in nonresidential areas, but with subsequent urban development, the refinery is now surrounded by highly populated areas (Al-Jahdali and Bin Bisher, 2008). The refinery has units for crude distillation, desulphurization of gasoline, diesel and kerosene, vacuum distillation and for asphalt manufacture and produces 60,000 barrels of oil daily (A Barrel Full). Indeed, a recent study identified elevated levels of PM2.5 arising from heavy fuel oil near the refinery, (Khodeir et al., 2012) while another suggested genotoxicity of nearby emissions, with DNA damage directly correlating with organic particulate and PAHs concentrations in the air samples (ElAssouli et al., 2007). Together, these findings suggest the potential for cardiovascular effects of air pollutants from the refinery for vulnerable subpopulations, including children.

In this manuscript, we describe airborne measurements of PM10 and PAH in schools in varying proximity to this large oil refinery, as well 1-hydroxypyrene and several mono-hydroxyphenanthrenes in the urine of children attending these schools. We also assessed associations of cardiovascular profiles in relationship to airborne and urinary measures of pollutants in these children.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

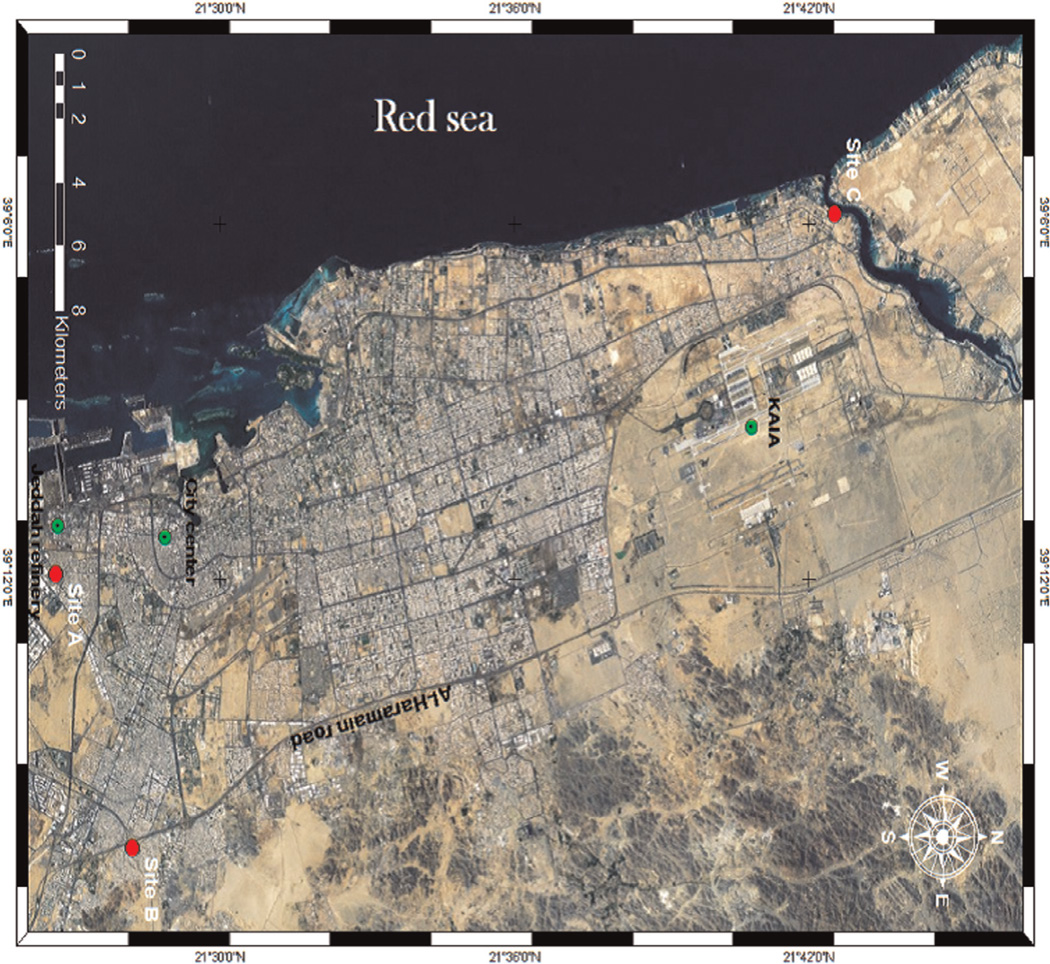

Three schools were identified in varying proximity to the oil refinery and to vehicular traffic. All students enrolled in the three schools were male, and lived within 1 km of the school. There are no mixed (male and female) schools in Saudi Arabia. The sampling sites in Jeddah city are shown in Fig. 1. Site one (A, School 1) is located in Ghulail district, south of the city, close to the port and only 700 m east of Jeddah oil refinery. The school belongs to a poor, highly populated residential area. Site two (B, School 2) is located in Al-Muntazahat District, East of Jeddah, adjacent to the ring road (Al-Haramain road) and 9.5 km east of the refinery. The area has a high population and heavy traffic density. Site three (C, School 3) is located in Al-Murjan District, situated directly on the Red Sea Creek (Sharm Obhur), 30.3 km to the north of the refinery and surrounded by resorts and a few residential areas. This school was selected because it was more likely to have “background” PM10 and PAH concentrations compared to schools near stationary and mobile sources of exposure, and is identified as the background school hereafter in the manuscript. Meterologic conditions (temperature, wind speed, pressure and relative humidity) were qualitatively similar across the three schools.

Fig. 1.

Study locations (red dots) in the context of locations of the refinery, city center and King Abdulaziz International Airport (KAIA, green dots).

At each of these three schools, all 10–14 year old children were approached about participation through their parents. Meetings at each school were held to explain the study objectives, sampling methods, and questionnaire guidelines. After obtaining signed and informed consent, questionnaires were administered to the parent, a urine sample was collected, and brachial artery distensibility and blood pressure were measured. On the eve of the sampling day, a guideline sheet, an individually labeled questionnaire, and a labeled sterile sampling tube were provided. They were instructed to get the first spot urine sample the next morning and bring back the samples together with the completed questionnaires to school for three consecutive days lagged one day from air sampling (Sunday–Tuesday). The exposure assessment questionnaire included information of child’s home characteristics, medical history, demographic factors, semi-quantitative food frequency, food sources, habits, and time–activity profile. Special emphasis was given regarding the consumption of charbroiled food and cigarette smoking during the previous seven days. Environmental assessments and urine sample collections were conducted simultaneously in all regions on the same days.

The study proposal was scrutinized and approved by King Abdulaziz University Research Ethics Committee (protocol number 700-12, approval date 4/1/2012). Dr. Trasande signed a self-certification that his participation did not represent human subjects research as defined by 45 CFR 46.102.

2.2. Air sample collection

Sampling was carried on the school’s roof at a height of approximately 9 m from the ground. Atmospheric PAH samples were collected using a USEPA pesticide sampler (Environmental Tisch, Cleveland-Ohio, USA) In which the air was drawn through a TSP inlet followed by a quartz microfiber filter (TE-QMA4 10.16 cm, Ohio, USA) to collect PAH compounds in the particulate phase and then through adsorbent polyurethane foam (PUF) to collect PAH compounds present in the gaseous phase. Fifteen daily 24–hr samples were collected from each school, with sampling beginning each day at 07:00 AM. The sampling flow rate was measured before and after sampling, and samples were collected during the period from February 23–April 23, 2013.

2.3. Body mass measurements

We measured weight and height and using calibrated stadiometers (Seca model 217; Hamburg, Germany) and scales (Beurer GmbH model PS07; Ulm, Germany). We derived Body Mass Index Z-scores from 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) norms, incorporating height, weight and gender; overweight and obese were categorized as BMI Z-score ≥ 1.036 and ≥ 1.64 (Ogden et al., 2002).

2.4. Cardiovascular measurements

The DynaPulse Pathway (PulseMetric, San Diego, CA) instrument derives brachial artery distensibility from arterial pressure signals obtained from a standard cuff sphygmomanometer (Brinton et al., 1997). The pressure waveform is calibrated and incorporated into a physical model of the cardiovascular system, assuming a straight tube brachial artery and T-tube aortic system. DynaPulse has been previously validated with high correlation between compliance measurements obtained during cardiac catheterization and noninvasive brachial methods (r = 0.83) (Brinton et al., 1997,, 1998) Reproducibility studies using blind duplicates demonstrated good intraclass correlation coefficients for arterial compliance, from which distensibility is calculated (0.72) (Urbina et al., 2011, 2010). Off-line analyzes of brachial artery pressure curves are performed using an automated system.

This yielded measurements of brachial artery distensibility, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, heart rate and pulse pressure. All measurements were averaged. Calculation of systolic and diastolic BP Z-scores utilized mixed-effects linear regression models described in The Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Height Z-scores, gender and age were input to compute expected systolic and diastolic BPs (derived from 1999–2000 NHANES data), and BP Z-scores were then calculated from the measured BPs using the formula Zbp = (x − μ)/σ, where x is the measured BP, μ is the expected BP, and σ is derived from the same NHANES data (National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in and Adolescents, 2004). Prehypertension was defined as SBP or DBP above the 90th percentile for age, height and sex.

2.5. Air analysis

Prior to sampling, the filters were preheated at 400 °C for 48 h in a box furnace, wrapped in clean preheated foil, placed in a cardboard box and sealed in an airtight metallic container. The PUF substrates were pre-cleaned prior to their use in the field by immersing in 100 mL of dichloromethane (DCM) and ultrasonicating at 20 °C for 30 min. The solvent was then drained and the PUF substrates were left to dry in a sealed metal container under a stream of nitrogen. The clean and dry PUF substrates were subsequently sealed in airtight plastic bags and stored in the freezer. Once exposed, the filter and PUF substrates were wrapped separately with clean preheated foil, enclosed in airtight plastic bags and stored at approximately − 18 °C.

Samples were analyzed for 14 PAH using the methodology described previously (Delgado-Saborit et al., 2013). Briefly, filter and PUF substrates were spiked with 1000 pg µL−1 deuterated internal standards for quantification. Filters were immersed in DCM and ultrasonicated for 15 min at 20 °C. The extract was subsequently dried and cleaned using a chromatography column filled with 0.5 g of anhydrous sodium sulfate (Puriss grade for high performance liquid chromatography, or HPLC). The extract was further concentrated to 50 µL under a gentle N2 flow. PUF substrates were immersed in 100 mL of DCM and ultrasonicated for 20 min at 20 °C. The sample was then concentrated to 10 mL using N2 and subsequently dried and cleaned as outlined for the filters above.

Samples were analyzed for PAH compounds using gas chromatography (6890, Agilent Technologies) equipped with a non-polar capillary column (Agilent HP-5MS, 30 m, 0.25 mm ID, 0.25 µm film thickness – 5% phenylpolysiloxane) in tandem with a mass spectrometer (5973N, Agilent Technologies).

2.6. Urine analysis

Determination of 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-hydroxyphenanthrene and 1-hydroxypyrene was carried out in urine samples pooled from multiple time points in each study participant using a method published by the German Research Foundation (1999). Urine samples of 6 ml were buffered with 12 ml 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0, and hydrolyzed with 80 µl glucuronidase/arylsulfatase for 16 h in a water bath at 37 °C. To separate the particulate matter, the solutions were centrifuged at 3000 r.p.m. for 15 min, and 12 ml of the supernatant fraction was transferred into an autosampler tube. Then, 3 ml of this solution was injected into the high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system by an autosampler. The HPLC system consisted of a quaternary gradient pump, a single-channel pump, a column thermostat (L 7350), an autosampler, a fluorescence detector (L 7480), an automatic six-way valve and a PC for integration. All HPLC instruments were from Merck-Hitachi (Darmstadt, Germany). The metabolites were enriched on a special precolumn consisting of copper phthalo-cyanine-modified silica gel, and were transferred on an RP-C 18 column (LiChrospher PAH 5 µm 250-4 with precolumn) by a column switching program.

After separation, the analytes were quantified by a switchable wavelength fluorescence detector. For the detection of the phenanthrene metabolites, the excitation wavelength was 244 nm and emission wavelength 370 nm. For the detection of 1-hydroxypyrene, the excitation wavelength of 236 nm and the emission wavelength of 386 nm were used. To quantify the co-eluting metabolites, the sum of 2- and 9-hydroxyphenanthrene was quantified by a calibration curve of 2-hydroxyphenanthrene. The limits of quantification were 16 ng/l urine for 1-hydroxyphenanthrene, 4 ng/l for 2/9-hydroxyphenanthrene, 5 ng/l for 3-hydroxyphenanthrene, 8 ng/l for 4-hydroxyphenanthrene and 12 ng/l for 1-hydroxypyrene. Creatinine in urine was determined photometrically as picrate according to the Jaffe method (Taussky, 1954).

2.7. Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyzes were performed on the children who participated in the study. Based upon knowledge of socioeconomic strata in the city of Jeddah, income was categorized into < 3000 Saudi Riyal (SR)/month (corresponding to < 800 US dollars/month), 3000–9000SR/month and >9000SR/month. Residence of smokers in the home was categorized into a dichotomous variable as was burning incense (sometimes/rarely versus always) and use of charbroiled food (none during day before urine collection versus once or more during the day before sampling). Means and standard deviations of particulate matter and total PAH as well as individual PAH compounds were computed, and compared by school location using an unpaired student’s T-test.

Univariate analyzes examined relationships of urinary 1-hydroxypyrene, total phenanthrenes, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, brachial artery distensibility, heart rate and pulse pressure with the above referenced sociodemographic and exposure variables. Multivariable analyzes were then performed on these outcomes, using p < 0.10 as a criterion for inclusion. For 1-hydroxypyrene and phenanthrene measurements, this resulted in exclusion of age, height and BMI Z-score in final multivariable models. Income category was included in the final multivariable model and subsequently excluded to assess potential effect modification on the school location-phenanthrene relationship. For cardiovascular measures, all sociodemographic and exposure covariates were included in final multivariable models in light of a strong literature suggesting socioeconomic relationships and tobacco smoke exposures with elevated blood pressure in children (Johnson et al., 2009; Weitzman et al., 2005) Multivariable models examined both continuous systolic and blood pressure and Z-scores to assess whether use of American normative data were influential on the results.

3. Results

184 Boys participated in the study (Table 1). The overall participation rate was 70.0% (63/88 from School 1, or 71.6%; 58/83 from School 2, or 69.8%; 63/92 from School 3, or 68.5%). All participants were born in their current residence. The mean age was 12.1 years (SD 1.2); 22.6% were overweight or obese, and 51.1% met pre-hypertension criteria. Participants were near-equally distributed from the three schools. As expected, there were significant differences in family income by school location, with children from lower income families in the schools near the ring road and the refinery. Substantial second-hand smoke (37.2%) and incense exposure (88.9% sometimes or always) were reported, and nearly half had ingested charbroiled food in the day before the urine collection. Use of charbroiled food was less frequent (p = 0.022) in the school away from the refinery without substantial nearby traffic (the “background” school), though BMI Z-scores were substantially higher (p = 0.002) and elevated BMI categories were more frequent (p = 0.004) in this school.

Table 1.

Description of the study population.

| Characteristica | Entire study population |

School near the oil refinery |

School located near a ring road |

Background school |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 12.1 (1.2) | 12.2 (1.0) | 11.7 (1.5) | 12.4 (1.1) |

| Body Mass Index | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 17.4 (15.4, 21.3) | 16.6 (15.4, 19.8) | 16.6 (14.8, 19.5) | 19.3 (16.2, 23.8) |

| Normal for age and sex (%) | 135 (75.8) | 52 (85.3) | 43 (79.6) | 40 (63.5) |

| Overweight but not obese (%) | 17 (8.0) | 5 (8.2) | 4 (7.4) | 8 (12.7) |

| Obese (%) | 26 (14.6) | 4 (6.6) | 7 (13.0) | 15 (23.8) |

| Blood pressure | ||||

| Mean systolic (SD) | 115.7 (10.1) | 118.5 (9.6) | 112.9 (9.9) | 115.3 (10.2) |

| Mean diastolic (SD) | 71.9 (7.4) | 75.5 (6.4) | 69.3 (7.3) | 70.8 (7.3) |

| Prehypertensive for age and height (%) | 51.1 | 68.8 | 37.0 | 46.0 |

| Brachial artery distensibility, mean (SD) | 7.49 (1.86) | 7.82 (1.79) | 7.54 (1.90) | 7.11 (1.87) |

| Heart rate, mean (SD) | 83.9 (11.5) | 82.2 (12.5) | 85.8 (9.8) | 83.9 (11.6) |

| Pulse pressure, mean (SD) | 53.5 (10.2) | 52.7 (9.7) | 52.9 (9.1) | 54.8 (11.4) |

| Urinary 1-hydroxypyrene (ng/g creatinine), median (IQR) | 261.4 (177.9, 492.6) | 272.3 (205.3, 448.1) | 352.3 (190.3, 567.4) | 191.2 (132.3, 426.4) |

| Urinary 1-hydroxyphenanthrene (ng/g creatinine), median (IQR) | 549.6 (355.9, 826.6) | 648.6 (375.3, 822.9) | 595.2 (391.1, 972.6) | 442.9 (295.4, 680.0) |

| School location | ||||

| School near the oil refinery (%) | 63 (34.2) | |||

| School located near a ring road (%) | 58 (31.5) | |||

| Background school (%) | 63 (34.2) | |||

| Family income | ||||

| Less than 3000 SR/month (%) | 56 (31.1) | 34 (54.0) | 21 (36.2) | 1 (1.7) |

| 3000–9000 SR/month (%) | 75 (41.7) | 25 (39.7) | 29 (50.0) | 21 (35.7) |

| Greater than 9000 SR/month (%) | 49 (27.2) | 4 (6.4) | 8 (13.8) | 37 (62.7) |

| One or more smokers at home (%) | 67 (37.2) | 25 (39.7) | 20 (34.5) | 22 (37.3) |

| Frequent use of incense (%) | 64 (35.6) | 26 (41.3) | 23 (39.7) | 15 (25.4) |

| Use of charbroiled food once or more in day before urine collection (%) |

73 (46.5) | 24 (40.0) | 20 (38.5) | 29 (64.4) |

All participants were male.

Substantial differences in PM10 and PAH were noted when the schools near the ring road and the oil refinery were compared to the school near the Red Sea (Table 2). PM10 and PAH did not differ substantially between the school near the ring road and the school near the oil refinery. Differences in total PAH of the schools near the ring road and the oil refinery with the “background” school were driven in magnitude by substantially higher phenanthrene concentrations (see Appendix), though nearly all PAHs measured were substantially higher in the other two schools compared with the school cited far from vehicular and point sources. Individual PAHs did not differ appreciably between the school near the ring road and the school near the oil refinery.

Table 2.

Concentration of total suspended particulate matter and total PAHs at different locations.

| School location | TSP (µg/m3) | ∑ (Particulate + gaseous) PAHs (ng/m3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Near the oil refinery |

444.09 | 143.26 | 36.75 | 17.28 |

| School located near a ring road |

395.45 | 65.33 | 30.28 | 8.20 |

| Background school |

232.41a | 137.00 | 12.33b | 7.53 |

All other comparisons p > 0.05.

TSP = Total Suspended Particles; PAH = Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons.

p = 0.0008 Compared to near ring road; p = 0.0003 compared to near oil refinery.

p < 0.0001 Compared to near ring road; p < 0.0001 compared to near oil refinery.

Univariate analyzes revealed interesting individual-level differences in urinary biomarkers of PAH exposure (Table 3), in which proximity to the ring road (p = 0.006) and the oil refinery (p = 0.016) were each associated with increases in 1-hydroxypyrene but not hydroxyphenanthrenes, whereas use of incense frequently was associated with substantially higher hydroxyphenanthrene concentrations (p = 0.004) but not 1-hydroxypyrene. The highest category of family income was also associated with significantly lower urinary 1-hydroxypyrene (p = 0.025). No socioeconomic, dietary, or household exposure factors were associated with blood pressure, though substantially higher diastolic blood pressure (4.71 mm Hg, 95% CI: 2.23, 7.18) was identified in the children near the refinery compared to the other groups. As expected, age, height and BMI Z-score were significantly associated with systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

Table 3.

Univariate analyses of 1-hydroxypyrene, total phenanthrene and blood pressure measurements against sociodemographic and exposure covariates.

| Characteristic | Increment in log-transformed 1-hydro- xypyrene, ng/g creatinine (95% CI) |

Increment in log-transformed total phenanthrene, ng/g creatinine (95% CI) |

Increment in systolic BP (95% CI) |

Increment in diastolic BP (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family income < 3000 SR/month | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Family income 3000–9000 SR/month (%) |

−0.14 (−0.41, 0.13) | −0.14 (−0.36, 0.08) | −0.99 (−4.64, 2.66) | −1.93 (−4.57, 0.71) |

| Family income greater than 9000 SR/ month (%) |

−0.36 (−0.69, −0.47)* | −0.11 (−0.38, 0.16) | −2.03 (−6.04, 1.98) | −2.29 (−5.19, 0.62) |

| Background school | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| School located near a ring road | 0.42 (0.12, 0.71)** | 0.20 (−0.05, 0.45) | −2.38 (−6.01, 1.25) | −1.51 (−4.06, 1.05) |

| School located near the oil refinery | 0.35 (0.07, 0.64)* | 0.14 (−0.10, 0.39) | 3.17 (−0.35, 6.69) | 4.71 (2.23, 7.18)*** |

| One or more smokers in home | 0.13 (−0.12, 0.38) | 0.05 (−0.15, 0.25) | −0.72 (−3.88, 2.43) | −0.67 (−2.97, 1.63) |

| Use of incense sometimes or rarely | −0.23 (−0.47, 0.02) | −0.29 (−0.49, −0.09)** | 1.50 (−1.66, 4.67) | 0.49 (−1.82, 2.80) |

| Use of charbroiled food once or more in day before urine collection |

0.06 (−0.18, 0.30) | 0.15 (−0.05, 0.34) | −1.14 (−4.38, 2.10) | −0.05 (−2.48, 2.39) |

| Age | −0.04 (−0.14, 0.05) | −0.02 (−0.11, 0.06) | 2.70 (1.55, 3.85)*** | 1.13 (0.25, 2.01)* |

| Height | −0.004 (−0.02, 0.01) | −0.002 (−0.013, 0.008) | 0.45 (0.30, 0.63)*** | 0.22 (0.10, 0.33)*** |

| BMI Z-score | −0.03 (−0.11, 0.05) | 0.05 (−0.02, 0.11) | 2.61 (1.72, 3.51)*** | 0.84 (0.14, 1.55)* |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Multivariable analyses identified substantially higher 1-hydroxypyrene concentrations in children attending the school near the ring road (Table 4), even after controlling for income category (107.3 ng/g creatinine, 95% CI: 6.4, 250.1). Children attending school near the oil refinery did have higher 1-hydroxypyrene concentrations compared to children attending the “background” school prior to controlling for income category (90.4 ng/g creatinine, 95% CI: 12.0, 1959) though this attenuated to nonsignificance on adding income category to the models (77.1 ng/g creatinine, 95% CI: − 17.7, 212.7), suggesting residual confounding. Associations with total hydroxyphenanthrenes differed in that the only significant association was with incense use, in which children living in homes with heavy incense use had 124.3 ng/g creatinine higher total hydroxyphenanthrenes than other children (95% CI: 27.1, 203.5).

Table 4.

Multivariable regression models of urinary 1-hydroxypyrene and total phenanthrene with sociodemographic and dietary characteristics.

| Characteristic | Increment in 1-hydroxypyrene, ng/g creatinine (95% CI) |

Increment in 1-hydroxypyrene, ng/g creatinine (95% CI) |

Increment in total phenan- threne, ng/g creatinine (95% CI) |

Increment in total phenan- threne, ng/g creatinine (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family income < 3000 SR/month | Reference | Reference | ||

| Family income 3000–9000 SR/ month (%) |

−7.7 (−64.2, 67.3) | −29.9 (−138.4, 107.1) | ||

| Family income greater than 9000 SR/month (%) |

−29.2 (−97.4, 72.3) | 13.7 (−147.1, 238.5) | ||

| Background school | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| School located near a ring road | 116.4 (29.5, 234.1)** | 107.3 (6.4, 250.1)* | 129.0 (−20.4, 320.8) | 141.7 (−32.9, 375.1) |

| School located near the oil refinery |

90.4 (12.0, 1959)* | 77.1 (−17.7, 212.7) | 85.1 (−51.1, 258.9) | 94.5 (−71.7, 318.0) |

| One or more smokers in home | 19.6 (−31.3, 84.6) | 19.4 (−36.6, 91.0) | 2.60 (−97.6, 125.1) | 1.6 (−100.8, 127.3) |

| Use of incense sometimes or rarely |

−33.1 (−73.3, 18.0) | −36.2 (−80.4, 20.4) | −125.8 (−203.2, −30.9)* | −124.3 (−203.5, −27.1)* |

| Use of charbroiled food once or more in day before urine collection |

29.7 (−22.8, 96.2) | 33.3 (−24.7, 107.1) | 98.8 (−16.8, 239.4) | 95.4 (−21.4, 238.0) |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Multivariable regression models revealed strong associations of school location near the refinery with blood pressure outcomes, however modeled, and controlling either for urinary total hydroxyphenanthrenes or 1-hydroxypyrene (Table 5). Increments of 6.01 mm Hg systolic (95% CI: 1.74, 10.27) and 6.44 mm Hg diastolic (95% CI: 3.08, 9.80) blood pressure, controlling for 1-hydroxypyrene, with similar associations when blood pressure Z-scores using US norms were applied or hydroxyphenanthrene was substituted for 1-hydroxypyrene. A 4.35-fold odds of prehypertension was identified (95% CI 1.42, 13.3) for attending school near the refinery, controlling for urinary 1-hydroxypyrene. Neither PAH biomarker was significantly associated with any blood pressure outcome, either in multivariable models with school location or without (data not shown). No differences in heart rate, pulse pressure, or brachial artery distensibility were significant.

Table 5.

Multivariable regression models of blood pressure in relationship to adiposity and PAH biomarkers.

| Characteristic | Increment in systolic BP (95% CI)a |

Increment in diastolic BP (95% CI)a |

Increment in systolic BP Z-score (95% CI)b |

Increment in diastolic BP Z-score (95% CI)b |

Odds ratio, prehypertension (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background school | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| School located near a ring road | 1.96 (−2.24, 6.15) | 0.08 (−3.21, 3.38) | 0.17 (−0.22, 0.56) | −0.002 (−0.28, 0.28) | 0.93 (0.31, 2.72) |

| School located near the oil refinery |

6.01 (1.74, 10.27)** | 6.44 (3.08, 9.80)*** | 0.56 (0.16, 0.96)** | 0.55 (0.26, 0.84)*** | 4.35 (1.42, 13.3)* |

| Log (urinary 1-hydroxypyrene) | −1.55 (−3.44, 0.35) | −0.49 (−1.98, 1.00) | −0.15 (−0.33, 0.03) | −0.05 (−0.17, 0.08) | 0.74 (0.45, 1.20) |

| School located near a ring road | 1.63 (−2.68, 5.93) | −0.04 (−3.42, 3.34) | 0.14 (−0.26, 0.54) | −0.01 (−0.30, 0.28) | 0.76 (0.25, 2.26) |

| School located near the oil refinery |

5.78 (1.47, 10.10)** | 6.33 (2.94, 9.72)*** | 0.53 (0.13, 0.94)*** | 0.54 (0.25, 0.83) | 3.83 (1.26, 11.6)* |

| Log (urinary total phenanthrene) | −1.71 (−4.06, 0.64) | 0.16 (−1.68, 2.01) | −0.17 (−0.39, 0.05) | 0.01 (−0.15, 0.17) | 0.83 (0.46, 1.52) |

Controlling for height, BMI Z-score, income category, smokers in home, use of incense, and age.

Controlling for BMI Z-score, income category, smokers in home, use of incense, and age.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

4. Discussion

The main finding of this manuscript is that attendance of a school near a Saudi Arabian oil refinery is significantly associated with elevated blood pressure. Substantially elevated PAH biomarkers were identified with attending school in proximity to the refinery or high traffic density, though the association with refinery proximity was subject to residual confounding by family income. Coupled with biologically plausible mechanisms, they raise potential concern about vulnerability of children to the early development of cardiovascular disease with chronic air pollutant exposure.

As would be expected from a hypothesis-generating, cross-sectional study, there are substantial limitations to interpretation. There are many well-known early life risks for cardiovascular disease (e.g., low birth weight (Barker, 1990; Barker and Osmond, 1986; Barker et al., 1992)) which we did not assess in the present study. Given the potential consequences of air pollutant exposure for fetal growth, an alternative hypothesis is that exposure during pregnancy may have produced the associations described here, insofar as children experienced their gestations in the same areas as they attended school. We also did not collect data on caloric or salt intake which could have also contributed to elevations in blood pressure (Yang et al., 2012). While a child spends forty hours or more per week at school, children could have lived in highly disparate areas with higher or lower PAH exposures that could have influenced cardiovascular parameters. Exposure imprecision is known to bias towards the null with categorical outcomes such as prehypertension, (Carroll, 1998; Fleiss and Shrout, 1977; Fuller, 1987) though the direction of this bias for the continuous outcomes is less clear. We did not exclude for preexisting medical conditions that could have contributed to the associations identified here, or other environmental chemical exposures, including phthalates and bisphenol A, which may independently contribute to insulin resistance, elevated blood pressure or signs of endothelial dysfunction including albuminuria (Trasande et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2014, 2013c). We were also unable to examine insulin resistance or oxidant stress biomarkers, which could both be mediators of the associations identified here. It is also important to recognize that the measurements of urinary biomarkers represent only a short snapshot of exposure, while the effects on cardiovascular outcomes are likely to be the result of chronic exposures which may not be well captured in the data for individual subjects, as even the pooled biomarker data from multiple time points reflect only exposures over the past 1–2 months.

The well-documented disparities in environmental exposures by socioeconomic status posed difficulty in our study (Freudenberg et al., 2011; Woodruff et al., 2003). We unfortunately could not identify a school located in a high socioeconomic status area near the refinery, and are aware that unmeasured dietary or environmental factors that coexist with low socioeconomic status could also have confounded the relationships of school location with PAH biomarkers, and school location with elevated blood pressure. While these caveats are appropriate, the study also has many strengths, including careful measurement of cardiovascular profiles in a way that minimizes “white coat hypertension,” (Sorof et al., 2001; Verdecchia et al., 1992) assessment of airborne as well as biological markers of PAH exposure, and assessment of multiple potential confounders (e.g., tobacco smoke exposure, incense burning) in three relatively homogeneous samples permitting careful comparison.

Ours is the first study to our knowledge to relate environmental measures and biomarkers to measures of peripheral arterial wall stiffness in children. Though associations with brachial artery distensibility were nonsignificant, it should be noted that the population in this study is younger than those previous studies and may have experienced too short a period of exposure to see an effect on distensibility (Urbina et al., 2011, 2010). The mean BMI in our study population is also much lower than in past studies, and the lower BMI in the school near the refinery compared with the background school could also have confounded our interpretation. The effect size may have been too small to detect at this young an age.

Air pollution is a complex mixture, and the absent association of PAHs with blood pressure in the study population raises interesting questions. Another plausible group of mediators of the PM effect on cardiovascular disease are heavy metals, especially nickel and vanadium, which are prominent, along with PAHs, in oil burning and refining (Bakker et al., 2000). Nickel and vanadium are also known to be potent oxidant stressors (Chen et al., 1998, 2003; Krejsa et al., 1997; Manzo et al., 1992; Stohs and Bagchi, 1995; Valko et al., 2005). Inhalation studies in mice have induced cardiovascular disease, and analyses of large longitudinal cohorts have also identified associations of high levels of these heavy metals in PM with increased adverse cardiovascular events (Dominici et al., 2007a, 2007b; Lippmann et al., 2006) We did not measure heavy metals in our study population, and especially in a highly exposed subpopulation such as children attending school near an oil refinery heavy metals or other unmeasured air pollutants could explain the association of blood pressure with proximity to the refinery.

The absent association of PAH biomarkers or proximity to the refinery or traffic with brachial artery distensibility in the presence of the association with blood pressure bears some mention. There is no gold standard for assessing arterial stiffness, with each method based on different physiologic assumptions (Woodman et al., 2005). While brachial artery distensibility is a robust measure of peripheral aortic stiffness, central aortic stiffness may have been more sensitive to detect the microvascular changes that would be induced by PAH or other air pollutant exposures. Pulse wave velocity in particular may therefore have been more useful. Given the alternative explanation that heavy metals in the PM may contribute uniquely to cardiovascular risk in our study population, it should be noted that heavy metals such as methylmercury have been documented to contribute to autonomic instability (Grandjean et al., 2004; Murata et al., 2006). While we did not measure heart rate variability in the present study, future work in such populations should consider the possibility of autonomic cardiovascular effects rather than oxidant stress-mediated endothelial dysfunction as the potential mechanism.

In conclusion, proximity to an oil refinery in Saudi Arabia is associated with prehypertension and increases in PAH and PM10 exposures. Further study including insulin resistance measurements, better control for confounding, and longitudinal measurement is indicated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, under Grant no. (3-10-1432/ HiCi). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR technical and financial support.

Abbreviations

- BP

Blood pressure

- BAD

Brachial artery distensibility

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- DCM

dichloromethane

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- PM

Particulate matter

- PM2.5

Particulate matter less than 2.5 µm in diameter

- PM10

Particulate matter less than 10 µm in diameter

- PAH

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- PUF

polyurethane foam

Appendix A

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2014.08.038.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

There are no competing financial or other interests to disclose.

References

- A Barrel Full, Jeddah Refinery. [Accessed 26.05.14]; Available from: < http://abarrelfull.wikidot.com/jeddah-refinery>. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jahdali M, Bin Bisher A. Sulfur dioxide accumulation in soil and plant leaves around an oil refinery: a case study from Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2008;4:84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo J, et al. Ambient particulate pollutants in the ultrafine range promote early atherosclerosis and systemic oxidative stress. Circ. Res. 2008;102:589–596. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae S, et al. Exposures to particulate matter and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and oxidative stress in schoolchildren. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;118:579–583. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker MI, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil and plant samples from the vicinity of an oil refinery. Sci. Total Environ. 2000;263:91–100. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(00)00669-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. (Editorial) Br. Med. J. 1990;301:1111. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6761.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Osmond C. Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischaemic heart disease in England and Wales. Lancet. 1986;1:1077–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJP, et al. The relation of fetal length, ponderal index and head circumference to blood pressure and the risk of hypertension in adult life. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 1992;6:35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1992.tb00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell ML, et al. Seasonal and regional short-term effects of fine particles on hospital admissions in 202 US counties, 1999–2005. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008;168:1301. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton TJCB, Kailasam MT, Brown DL, Chio S-S, O’Conor DT, DeMaria AN. Development and validation of a noninvasive method to determine arterial pressure and vascular compliance. Am. J. Cardiol. 1997;80:323–330. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00353-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton TJWE, Chio SS. Validation of pulse dynamic blood pressure measurement by auscultation. Blood Press. Monit. 1998;3:121–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, et al. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the expert panel on population and prevention science of the american heart association. Circulation. 2004;109:2655–2671. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128587.30041.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstyn I, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and fatal ischemic heart disease. Epidemiology. 2005;16:744–750. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000181310.65043.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RJ. Measurement Error in Epidemiologic Studies. In: Armitage P, Colton T, editors. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. New York (NY): John Wiley & Sons; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-Y, et al. Association between oxidative stress and cytokine production in nickel-treated rats. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998;356:127–132. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-Y, et al. Nickel-induced oxidative stress and effect of antioxidants in human lymphocytes. Arch. Toxicol. 2003;77:123–130. doi: 10.1007/s00204-002-0427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang H-C, et al. Vasoactive alteration and inflammation induced by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and trace metals of vehicle exhaust particles. Toxicol. Lett. 2012;214:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Iii JD, et al. Exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and serum inflammatory markers of cardiovascular disease. Environ. Res. 2012;117:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Onis M, et al. Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among preschool children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010;92:1257–1264. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Saborit JM, et al. Analysis of atmospheric concentrations of quinones and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in vapour and particulate phases. Atmos. Environ. 2013;77:974–982. [Google Scholar]

- Dockery DW, et al. An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. New Engl. J. Med. 1993;329:1753–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici F, et al. Does the effect of PM10 on mortality depend on PM nickel and vanadium content? A reanalysis of the NMMAPS data. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007a;115:1701–1703. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici F, et al. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2006;295:1127–1134. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici F, et al. Particulate air pollution and mortality in the united states: did the risks change from 1987 to 2000? Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007b;166:880–888. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElAssouli S, et al. Genotoxicity of air borne particulates assessed by comet and the salmonella mutagenicity test in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2007;4:216–223. doi: 10.3390/ijerph2007030004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett CJ, et al. Association of urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and serum C-reactive protein. Environ. Res. 2010;110:79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL, Shrout PE. The effects of measurement errors on some multivariate procedures. Am. J. Public Health. 1977;67:1188–1191. doi: 10.2105/ajph.67.12.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N, et al. Strengthening community capacity to participate in making decisions to reduce disproportionate environmental exposures. Am. J. Public Health. 2011;101:S123–S130. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller WA. Measurement Error Models. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Commission for the Investigation of Health Hazards of Chemical Compounds in the Work Area, editor. Analyses of Hazardous Substances in Biological Materials. Weinheim: WILEY-VCH; 1999. German Research Foundation, PAH metabolites (1-hydroxyphenanthrene, 4-hydroxyphenanthrene, 9-hydroxyphenanthrene, 1-hydroxypyrene)-determination in urine; pp. 163–187. [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, et al. Cardiac autonomic activity in methylmercury neurotoxicity: 14-year follow-up of a Faroese birth cohort. J. Pediatr. 2004;144:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison D, et al. Role of oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2003;91:7–11. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WD, et al. Prevalence of risk factors for metabolic syndrome in adolescents: national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES), 2001–2006. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2009;163:371–377. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodeir M, et al. Source apportionment and elemental composition of PM2.5 and PM10 in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2012;3:331–340. doi: 10.5094/apr.2012.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korashy HM, El-Kadi AOS. The Role of Aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases. Drug Metab. Rev. 2006;38:411–450. doi: 10.1080/03602530600632063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejsa CM, et al. Role of Oxidative Stress in the Action of Vanadium Phosphotyrosine Phosphatase Inhibitors: REDOX INDEPENDENT ACTIVATION OF NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:11541–11549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SS, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–2260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann M, et al. Cardiovascular effects of nickel in ambient air. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006;114:1662–1669. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzo L, et al. Metabolic studies as a basis for the interpretation of metal toxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 1992;64–65:677–686. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(92)90247-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K, et al. Subclinical effects of prenatal methylmercury exposure on cardiac autonomic function in Japanese children. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 2006;79:379–386. doi: 10.1007/s00420-005-0064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Pesticides in the Diets of Infants and Children. 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics Version. Pediatrics. 2002;109:45–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polidori A, et al. Source proximity and residential outdoor concentrations of PM2.5, OC, EC, and PAHs. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2010;20:457–468. doi: 10.1038/jes.2009.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner B, et al. Childhood blood pressure trends and risk factors for high blood pressure: the NHANES experience 1988–2008. Hypertension. 2013;62:247–254. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Network. Jeddah. [Accessed 26.05.14];2008 Available from: < http://www.the-saudi.net/saudi-arabia/jeddah/>. [Google Scholar]

- Singh U, Jialal I. Oxidative stress and atherosclerosis. Pathophysiology. 2006;13:129–142. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorof JM, et al. Evaluation of white coat hypertension in children: importance of the definitions of normal ambulatory blood pressure and the severity of casual hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2001;14:855–860. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohs SJ, Bagchi D. Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995;18:321–336. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00159-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, et al. Cardiovascular effects of ambient particulate air pollution exposure. Circulation. 2010;121:2755–2765. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.893461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taussky HH. A microcolorimetric determination of creatine in urine by the Jaffe reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1954;208:853–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trasande L, et al. Bisphenol A exposure is associated with low-grade urinary albumin excretion in children of the United States. Kidney Int. 2013a;83:741–748. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trasande L, et al. Urinary phthalates are associated with higher blood pressure in childhood. J. Pediatr. 2013b;163:747.e1–753.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trasande L, et al. Dietary phthalates and low-grade albuminuria in US children and adolescents. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014;9:100–109. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04570413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trasande L, et al. Urinary phthalates and increased insulin resistance in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2013c;132:e646–e655. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-4022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trasande L, Thurston GD. The role of air pollution in asthma and other pediatric morbidities. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;115:689–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina EM, et al. Cardiac and vascular consequences of pre-hypertension in youth. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2011;13:332–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina EM, et al. Increased arterial stiffness is found in adolescents with obesity or obesity-related type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Hypertens. 2010;28:1692–1698. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833a6132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M, et al. Metals, toxicity and oxidative stress. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005;12:1161–1208. doi: 10.2174/0929867053764635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdecchia P, et al. Variability between current definitions of ‘normal’ ambulatory blood pressure. Implications in the assessment of white coat hypertension. Hypertension. 1992;20:555–562. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.20.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman M, et al. Tobacco smoke exposure is associated with the metabolic syndrome in adolescents. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2005;112:862–869. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.520650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman RJ, et al. Assessment of central and peripheral arterial stiffness: studies indicating the need to use a combination of techniques. Am. J. Hypertens. 2005;18:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff TJ, et al. Disparities in exposure to air pollution during pregnancy. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003;111:942. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, et al. Studying associations between urinary metabolites of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and cardiovascular diseases in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2010;408:4943–4948. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, et al. Studying the effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on peripheral arterial disease in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;461–462:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.04.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, et al. Sodium intake and blood pressure among US children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2012;130:611–619. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.