Abstract

The function and localization of proteins and peptides containing C‐terminal “CaaX” (Cys‐aliphatic‐aliphatic‐anything) sequence motifs are modulated by post‐translational attachment of isoprenyl groups to the cysteine sulfhydryl, followed by proteolytic cleavage of the aaX amino acids. The zinc metalloprotease ZMPSTE24 is one of two enzymes known to catalyze this cleavage. The only identified target of mammalian ZMPSTE24 is prelamin A, the precursor to the nuclear scaffold protein lamin A. ZMPSTE24 also cleaves prelamin A at a second site 15 residues upstream from the CaaX site. Mutations in ZMPSTE24 result in premature‐aging diseases and inhibition of ZMPSTE24 activity has been reported to be an off‐target effect of HIV protease inhibitors. We report here the expression (in yeast), purification, and crystallization of human ZMPSTE24 allowing determination of the structure to 2.0 Å resolution. Compared to previous lower resolution structures, the enhanced resolution provides: (1) a detailed view of the active site of ZMPSTE24, including water coordinating the catalytic zinc; (2) enhanced visualization of fenestrations providing access from the exterior to the interior cavity of the protein; (3) a view of the C‐terminus extending away from the main body of the protein; (4) localization of ordered lipid and detergent molecules at internal and external surfaces and also projecting through fenestrations; (5) identification of water molecules associated with the surface of the internal cavity. We also used a fluorogenic assay of the activity of purified ZMPSTE24 to demonstrate that HIV protease inhibitors directly inhibit the human enzyme in a manner indicative of a competitive mechanism.

Keywords: Isoprenoid, CaaX protease, zinc, metalloprotease, ZMPSTE24, membrane protein, progeria, enzyme inhibitor, HIV protease inhibitor, X‐ray crystallography, progeria

Short abstract

PDB Code: 5SYT

Abbreviations

- APS

advanced photon source

- CaaX

cys‐aliphatic‐aliphatic‐anything

- C12E7

heptaethyleneglycol mono n‐dodecyl ether

- C8E4

(hydroxyethyloxy)tri(ethyloxy)octane)

- C10E5

pentaethylene glycol monodecyl ether

- DDM

n‐dodecyl‐β‐maltoside

- HGPS

Hutchinson‐Gilford Progeria Syndrome

- ICMT

isoprenylcysteine carboxylmethyltransferase

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

Introduction

Modification of proteins by isoprenoid groups is important in diverse biological processes. Attachment of either a farnesyl (C15) or geranylgeranyl (C20) group, both cholesterol biosynthetic intermediates, to protein cysteine side chains leads to targeting of modified proteins to membranes, but also affects additional protein functions, including protein–protein interactions involved in cell signaling. The most common class of prenylated proteins is comprised of those containing “CaaX” (Cys, aliphatic, aliphatic, anything) sequences at their extreme C‐termini, where the prenyl group is attached via a thioether linkage to the cysteine residue of the CaaX motif. The ∼20 proteins in mammalian cells that are known to be prenylated at CaaX sequences1, 2 include the nuclear scaffold precursor prelamin A, small G proteins (including the products of Ras oncogenes), subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins, and the heat shock protein Hsp40. Based on the importance of Ras prenylation for signaling function, protein processing steps associated with the prenyl modification have been the target of a significant drug development effort for cancer therapy.

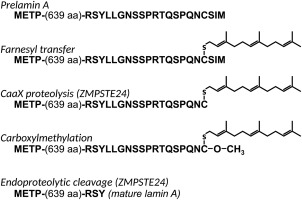

Attachment of prenyl groups to proteins, catalyzed by either farnesyl transferase or geranylgeranyl transferase, is generally accompanied by at least two additional protein processing steps: proteolytic removal of the aaX sequence and carboxylmethylation of the newly formed C‐terminus (Fig. 1). Carboxylmethylation is carried out by the enzyme ICMT (isoprenylcysteine carboxylmethyltransferase). The proteolytic step is catalyzed by either of two unrelated enzymes, Ste24 and Rce1 (Ras converting enzyme). Rce1 is responsible for processing of ras and the Gα subunit of heterotrimeric G proteins. Human ZMPSTE24 has, to date, only one known substrate, the precursor form of the nuclear scaffold protein lamin A. Maturation of prelamin A requires sequential cleavage by ZMPSTE24 at two sites: one of them at the cysteine of the CaaX sequence and the other 15 amino acids upstream from the first (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of prelamin A processing. The C‐terminal sequence of prelamin A is indicated with processing steps. CaaX proteolysis and the final endoproteolytic step are catalyzed by ZMPSTE24, although the alternative protease RCE1 may also be capable of catalyzing the CaaX cleavage step.

Loss of function of human ZMPSTE24 or mutation of the upstream ZMPSTE24 cleavage site in prelamin A results in progeria, premature aging.3 Complete loss of ZMPSTE24 activity leads to the autosomal recessive disease restrictive dermopathy, which results in death in utero or shortly after birth, with tight skin and abnormal joints, a phenotype that is recapitulated in mouse knockout models.4 A more mild disorder, mandibuloacral dysplasia (Type B) is caused by partial loss of ZMPSTE24 function that results in lipodystrophy (loss of subcutaneous fat) and skeletal abnormalities.5 A severe progeria, Hutchinson‐Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS), results from a mutation that introduces an RNA splicing site in prelamin A that leads to deletion of 50 amino acids, including the upstream site of cleavage by ZMPSTE24.6 The pathologies associated with these conditions appear to result primarily from accumulation of partially processed prenylated prelamin A retaining the farnesylated C‐terminus (progerin), since the pathology can be partially ameliorated by decreasing prelamin A expression in a mouse model7 and by farnesyl transferase inhibitors in humans8 and mice.9 In addition, several studies have reported increased abundances of partially processed prelamin A as a correlate of normal aging.10, 11, 12

It has also been proposed that ZMPSTE24 is responsible for off‐target effects of some (but not all) HIV protease inhibitors, since it is inhibited by these compounds in vitro,13, 14 since increased levels of partially processed prelamin A are found in cells treated with protease inhibitors,15 and since lipodystrophy is seen both in patients undergoing long term anti‐retroviral therapies and in patients with genetic lamin processing defects.16

The structures of Ste24 proteins from humans and yeast have been determined to moderate resolution (anisotropically to 3.4 Å and to 3.1 Å, respectively).17, 18 The structures of the enzymes from the two organisms are quite similar, consisting of seven transmembrane segments and a cytoplasmic cap enclosing a very large internal cavity containing a zinc atom with surrounding residues in a configuration nearly identical to that of the active site of thermolysin. This unusual structure raises many questions relevant to understanding Ste24 function, including the mode of entrance and egress of substrates into and out of the cavity, the mechanism by which an enzyme with only one active site catalyzes proteolytic cleavage at two distinct sites in a single substrate, the interplay between proteolysis and carboxylmethylation of prenylated substrates (since the carboxylmethyl transferase appears to be capable of acting at a stage between the two proteolytic events catalyzed by Ste24 19), and the mechanism of inhibition of proteolysis by HIV protease inhibitors designed to act on an aspartyl protease that is quite distinct from Ste24.

We report here the purification of human ZMPSTE24 from a yeast expression system and the use of the yeast‐expressed protein to achieve improved resolution of the enzyme's structure and to test the effects of HIV protease inhibitors directly on the purified enzyme.

Results

Purification and crystal structure of yeast‐expressed human ZMPSTE24

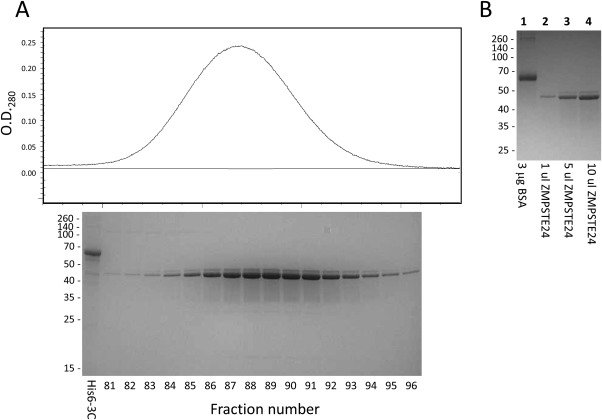

A synthetic ZMPSTE24 gene that was codon optimized for yeast expression (Supporting Information Fig. S1) was transformed into yeast under control of the ADH2 promoter as a C‐terminal fusion to a cleavable ZZ‐His10 tag as described previously.20 The resulting human protein could be expressed to levels allowing purification of multiple mg of protein from a 9 liter fermenter culture. ZMPSTE24 could be readily solubilized from yeast membranes using dodecylmaltoside (DDM) and then purified by affinity chromatography accompanied by exchange into the polyoxyethylene detergent C12E7 following protocols originally established for yeast Ste24p.17, 20 As shown in Figure 2, the preparation of purified protein after size exclusion chromatography contains a minor band that migrates slightly slower on SDS gels than the major species. This could be the result of myristoylation at the N‐terminal Met‐Gly sequence, which can serve as an acceptor for myristoylation. (The presence of glycine in the second position is preserved in many, but not all, mammals.)

Figure 2.

Expression and purification of ZMPSTE24. A. Aligned size exclusion chromatogram following affinity purification and SDS polyacrylamide gel of relevant fractions. The fraction numbers refer to 0.8 mL fractions (column bed volume 120 mL). The first lane (His6‐3C) contained 2.5 μg of purified His6‐tagged rhinovirus 3C protease as a reference. B. Quantitation of purified ZMPSTE24 relative to BSA.

Small crystalline rods of ZMPSTE24 measuring approximately 10–20 μm in the smallest dimensions were obtained in the presence of 150 μM lopinavir. Some of these diffracted anisotropically to ∼1.8 Å resolution (based on a CC1/2 cut‐off of 0.3) using the microbeam capability of the beamline 23‐ID_C of the APS. The program Blend21 was used to combine four of the highest resolution datasets (two of which were derived from the same crystal) to yield the merged dataset extending to an overall resolution of approximately 2.0 Å as described in Table 1. The structure was solved by molecular replacement based on the previously‐determined lower resolution structure (PDB: 4AW6).18 Following initial processing in the space group P1 with two molecules per asymmetric unit, no significant differences were detected between symmetry‐related monomers. Subsequent processing was performed in space group C2, with one molecule per asymmetric unit. The structure was refined to an R work/R free of 22%/25% but could not be refined further, despite the relatively high resolution of the merged datasets. This could reflect the inherent disorder or flexibility of the this transmembrane protein, as little or no density was observed for portions of the map corresponding to the extreme N‐terminal residues of ZMPSTE24 and two internal sections of sequence, precluding modeling of these segments of the protein.

Table 1.

Merged X‐ray Data

| Data collection statisticsa | |

| Unit cell dimensions (a,b,c)(Å) | 149.5, 84.6, 76.9 |

| Unit cell angles (α,β,γ)(°) | 90.0, 119.1, 90.0 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 33.6–2.0 (2.05–2.0) |

| R merge (%) | 43.9% (349%) |

| R pim (%) | 11.6% (90.9%) |

| CC1/2 (%) | 99.3 (57.4) |

| Mean I/σ | 6.7 (1.6) |

| Completeness for range (%) | 99.6 (97.8) |

| No. of reflections (total/unique) | 830724/56449 |

| Multiplicity | 14.7 (14.8) |

| Refinement statistics b | |

| R work/R free | 22%/25% |

| Average B factor | 37.61 |

| Number of non‐hydrogen protein atoms | 4006 |

| Protein residues | 444 |

| RMS (angles)(°) | 1.26 |

| RMS (bonds)(Å) | 0.012 |

| Validation statistics b | |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 96% |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 3.4% |

| Clash score | 6.2 (95th percentile) |

Statistics calculated using the program Aimless (17) for four datasets merged using Blend (18). Data collection statistics for the highest‐resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

Statistics calculated using the program Generate Table 1 of the Phenix program suite (1).

cStatistics generated using the MolProbity web server (11).

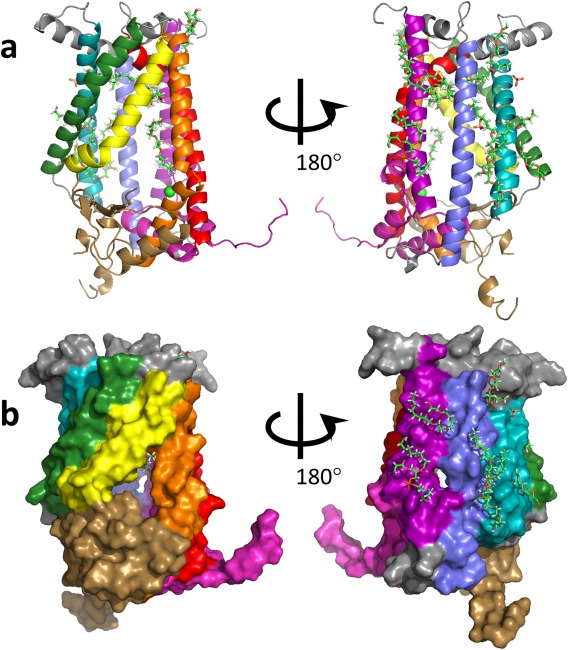

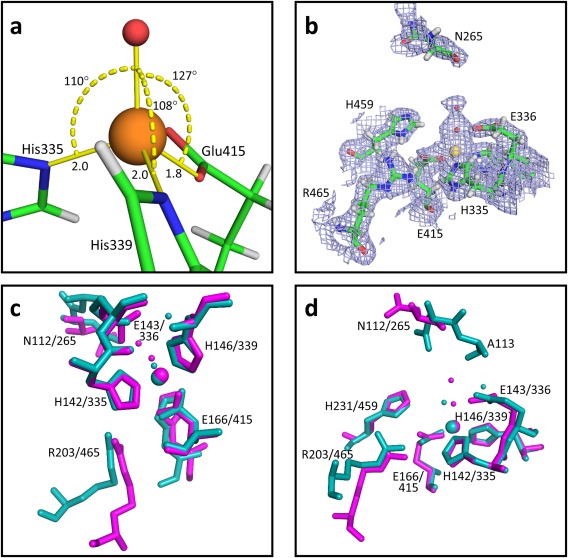

The overall fold and identified secondary structural elements of the high resolution ZMPSTE24 structure are congruent with the previously‐determined structures of the yeast and human enzymes (Fig. 3), however, transmembrane helices I, III, and VI contain one extra helical turn compared with the comparable elements in the structure of the yeast protein. The enhanced resolution of the current structure allows identification of a number of densities corresponding to ordered water molecules. (A total of 165 water molecules are included in the final modeled structure). Notable among these are two waters near the catalytic zinc atom in the active site, 2.0 Å and 4.1 Å from the center of mass of the zinc, forming a line pointing toward the zinc (see Fig. 4). These waters, together with three liganding amino acids from the protein form an approximately tetrahedral arrangement around the zinc [see Fig. 4(A)]. Water in the active site of ZMPSTE24 has been implicated in the catalytic mechanism based on the high degree of similarity of this site to the zinc‐containing site of the well‐studied protease thermolysin.17, 18 As shown in Figure 4(C,D), when the active sites of thermolysin (PDB code: 8TLN22) and ZMPSTE24 are aligned, the closest water in the thermolysin structure is 0.8 Å from the nearer of the two waters in the ZMPSTE24 structure (and 2.2 Å from the zinc center). It has been postulated that a zinc‐liganded catalytic water in thermolysin is displaced upon substrate binding by thermolysin.23 The current results suggest that the exact geometry of the liganding water may not be critical. In fact, the positions of the water molecules closest to the zinc vary considerably among different available native thermolysin structures (see PDB codes 8TLN,22 1LND24 and 1KEI).

Figure 3.

Overall structure of ZMPSTE24. The angles of view and coloring of secondary structure elements are as presented for yeast SmSte24p by Pryor et al.17 i.e. helix I, purple; helix 2, blue; helix 3, cyan; helix IV, green, helix V, yellow, helix Vi, orange; helix VII, red; cytosolic loop 5 domain, brown, C‐terminus, pink. a) Cartoon view. b) Surface representation. The zinc atom is shown in light green. Presumed lipid, sulfate, and polyethylene glycol or detergent molecules are shown as stick representations.

Figure 4.

ZMPSTE24 active site. a) The positions of three residues in the closest proximity to the zinc are shown. Zinc is shown as an orange sphere. The water molecule in closest proximity to the zinc is shown as a small red ball. Bond angles and distances (Å) are indicated. b) Map of electron density (2Fo‐Fc, contoured at 1σ) serving as the basis for modeling two water molecules immediately adjacent to the zinc. c) and d) Two views of a comparison of the active sites of thermolysin (PDB:8TLN) and ZMPSTE24. Atoms from thermolysin are shown in cyan, atoms from ZMPSTE24 are shown in magenta. Labels indicate the position of the indicated residues in thermolysin/ZMPSTE24). Zinc is shown as a large sphere. Water molecules closes to the zinc are shown as small balls with appropriate coloring. The structures were aligned using the PDB Superpose function of the Phenix suite based on the three residues closest to the zinc (H142/335, H146/339, and E166/415). The positions of eight residues from thermolysin that were previously found to adopt similar positions in yeast Ste24p17 are indicated. Only seven of these positions are found in the ordered regions of ZMPSTE24.

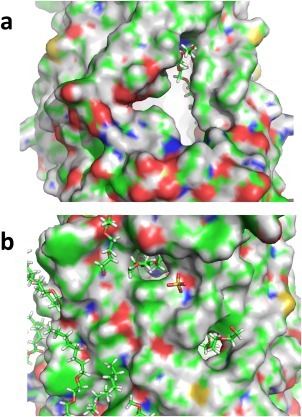

A striking feature of the ZMPSTE24 structure is the large opening between helices V and VI connecting the external surface of the bundle of transmembrane helices with the interior cavity (Fig. 5). This T‐shaped opening extending ∼15 Å in one dimension and ∼10 Å in the perpendicular direction is larger than the fenestrations seen in the previous structures, consistent with this opening serving a route for substrate entry into and egress from the active site in the cavity. The enlargement of the opening compared to previous structures stems from a lateral pivoting of transmembrane segment V away from transmembrane segment VI and from a lack of density for portions of the loop connecting segments V and VI (see below) compared to previous structures. The orientation of the opening with respect to the active site is such that the C‐terminus of prelamin A could extend inward through the opening in the proper orientation for cleavage, based on the previously reported correspondence between the active sites of Ste24 enzymes and thermolysin and on the previously determined structure of ZMPSTE24 in complex with a small substrate analog.18 One corner of the opening contains a cylindrical density extending from inside to outside that we have modeled as detergent. The similarity in shape between this density and a farnesyl chain suggests that this could be the pathway by which the protein‐attached prenyl group enters the cavity.

Figure 5.

Large fenestration. a. The figure shows the largest fenestration in ZMPSTE24 (surface representation), along with a detergent molecule modeled into density protruding through the opening. b. Smaller fenestrations in ZMPSTE24 also shown with modeled protruding detergent molecules. Surfaces of modeled carbon atoms are shown in green, hydrogen in grey, nitrogen in blue, oxygen in red, and sulfur in yellow.

Two regions of ZMPSTE24 are missing from the electron density in the current structure (see Supporting Information Fig. S2): (1) N‐terminal residues 1–9. Less of the N‐terminus is ordered than was observed in one monomer of the previous ZMPSTE24 structure. This could be due to differences in crystal packing or, possibly, to post‐translational modification of part of the population of ZMPSTE24 monomers, as indicated by the extra species seen during purification. (2) Residues 266–274 and 293–310 in the cytoplasmic‐facing Loop 5 Domain17 between transmembrane helices V and VI. A portion of this region was also missing in the low resolution structure of the human protein.18 The region was well‐ordered in the structure of yeast Ste24p, however, the human form of the protein contains a 36‐amino acid insertion in the region, compared to the yeast orthologs. Based on proximity to the large opening to the internal cavity in this region, flexibility of this cytoplasmic loop could play an important role in modulating accessibility of the cavity to substrates and products of ZMPSTE24 activities. The extra sequence in this region of the human protein, which is quite hydrophilic (containing a total of 17 positively and negatively charged residues), may be involved in recognizing the prelamin A substrate, compared to the rather simpler mating pheromone substrate in yeast. However, the fact that the human protein complements a yeast ste24 deletion indicates that the presence of the extra sequence elements does not abrogate recognition or entry into the cavity by pheromone precursor.

The C‐terminal segment of the current structure is better ordered than in either of the previous Ste24 structures. Density is observed for residues extending into the 3C protease cleavage site of the appended C‐terminal tag extending away from the main body of the protein in the cytoplasmic compartment. The present structure also exhibits density in the ER‐facing loop region encompassing residues 108–115 of human ZMPSTE24, a region that has been missing from previous structures. Yeast Ste24p proteins contain three extra residues inserted into this region compared to the human protein. However, despite the evident density for this region in the current structure, the loop appears to adopt a strained conformation, based on the difficulty of fitting the observed density to favorable backbone angles and rotamers (see Supporting Information Fig. S3). The roles of residues on the ER‐facing portions of ZMPSTE24 are not known, however, a human mutation (L94P) at this face severely impairs enzyme activity.25

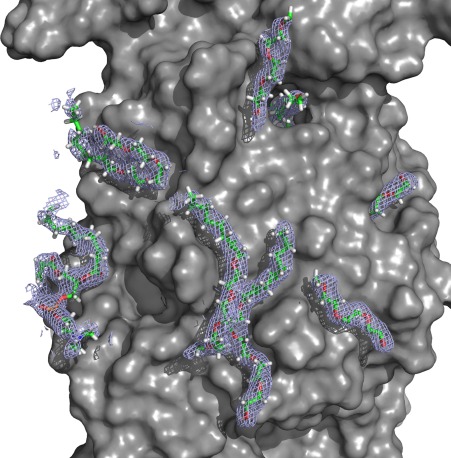

Several examples of extended snake‐like density were observed that could not be readily fit to protein chain. (Fig. 6) Most of these were fit and refined as molecules of C8E4 ((hydroxyethyloxy)tri(ethyloxy)octane)) or C10E5 (pentaethylene glycol monodecyl ether), depending on their lengths, as ordered fragments of the C12E7 detergent that is known to be bound to ZMPSTE24. (A less likely alternative, is that these are molecules of polyethylene glycol from the crystallization cocktail, since the structure of the head groups of polyoxyethylene detergents is indistinguishable from polyethylene glycol.) In one case, connected adjacent extended densities were modeled as a molecule of 1,2‐diacyl‐sn‐glycero‐3‐phosphocholine. Most of these presumed lipid/detergent chains are packed against the external surface of the protein in locations that would be expected to contact lipid when the protein is in native membranes. However, strikingly, three of them appear to traverse the fenestrations linking the internal cavity to the external surface. In these positions, they could serve to plug holes in the barrier surrounding the cavity or they could represent intermediates trapped in the pathways by which farnesylated substrates transit in and out of the cavity. None of these densities are in positions into which lipid chains were modeled in the previous ZMPSTE24 structure.18

Figure 6.

Lipid‐like densities. Electron density and modeled detergent and phospholipid molecules are represented by the mesh and the molecular stick representations. The figure was generated as a 2Fo‐Fc map using mesh at a contour level of 1.0σ showing all electron density within a distance of 2.0 Å of the modeled lipids and detergents.

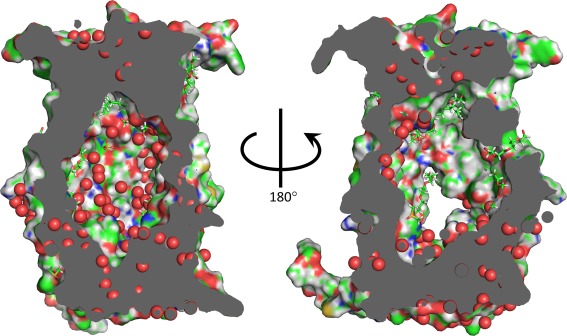

The current structure contains several clues to the nature of the internal cavity. The cavity contains two entire lipid/detergent densities, as well as portions of densities for molecules traversing the fenestrations into the cavity. These all reside in the ER‐facing half of ZMPSTE24, suggesting that this portion of the cavity is capable of accommodating small ligands with some hydrophobic character (Fig. 7). On the other hand, modeling of water into the structure uncovered many putative ordered waters internal to the cavity, as well as numerous additional sites in the cytoplasmic and ER‐facing extra‐membrane regions, but few sites on the outside of the transmembrane region (Fig. 7). As noted previously,18 the electrostatic surfaces in the interior of the cavity of ZMPSTE24 are predominantly negatively charged. This may facilitate the interaction with zinc, which was not included in the electrostatic calculations. However, the vicinity of the CaaX sequence at extreme C‐terminus of prelamin A lacks charged amino acids and thus is likely to be predominantly negatively charged, due to the C‐terminal carboxyl. This makes it unlikely that the CaaX sequence would interact anywhere other than in the immediate vicinity of the zinc. In contrast, the vicinity of the upstream cleavage site contains no pre‐existing carboxyl and the nearest charged residues are two arginines, one located three residues to the N‐terminal side of the cleavage site and the other, less likely to be relevant, located eight residues to the C‐terminal of the cleavage site. If charge‐charge interactions between the CaaX site and the zinc play a role in positioning this substrate, it is hard to see how similar interactions could be involved in the upstream cleavage.

Figure 7.

Cavity. Views of the interior of the ZMPSTE24 cavity. Modeled lipids, detergents and small molecules are shown as stick representations. Surfaces of modeled carbon atoms are shown in green, hydrogen in grey, nitrogen in blue, oxygen in red, and sulfur in yellow. The positions of modeled waters are shown as red spheres.

The highest resolution diffraction was obtained with crystals grown in the presence of the HIV protease inhibitor lopinavir. Additional crystals that were isomorphous, but did not diffract as well, were obtained in the absence of any inhibitor and in the presence of a different inhibitor, tipranovir. Following merging of multiple datasets obtained for the thin rod‐like crystals obtained under each condition, Fourier difference maps comparing the different crystals with and without inhibitors were calculated. Inspection of these maps failed to reveal any densities that could be interpreted as being due to the presence or absence of the inhibitors. The most significant feature of the maps was a change in the density of the zinc binding site, perhaps representing a difference in zinc occupancy in the different samples (note that zinc was not maintained in solution during purification and crystallization.)

Thus, although inhibitors were present in crystallization cocktails at concentrations well above the K i values for the inhibition of proteolysis (see below), they do not appear to be bound in any well‐ordered configuration in the crystals. This could mean that the observed inhibition is the result of multiple modes of binding with too low occupancy to be apparent in the crystal structure or that the binding is affected by differences between the crystallization conditions and the conditions under which inhibition of activity is measured, such as the elevated detergent and PEG concentrations used in crystal growth.

Inhibition of purified ZMPSTE24 by HIV protease inhibitors

Some of the side effects of HIV protease inhibitors have been proposed to arise from interactions of these drugs with ZMPSTE24. This is based, in part, on effects such as lipodystrophies that occur both in individuals with defects in prelamin A processing and in HIV‐infected people undergoing treatment with retroviral therapies that include the protease inhibitors.15, 16 In cellular systems, treatment with the protease inhibitors results in increased accumulation of incompletely processed prelamin A.13, 15, 26 Inhibition of the enzymatic activity of purified yeast Ste24p by the inhibitors has been reported to occur at inhibitor concentrations comparable to those that arise in patients who are maintained on anti‐retroviral therapies.13, 14, 27 Similar concentrations have been reported to inhibit purified yeast Ste24p28 and crude membrane fractions from yeast expressing mouse ZMPSTE24.13, 14 Both these findings were based on the use of an indirect assay of protease‐dependent carboxylmethylation of the precursor to yeast mating pheromone a‐factor. Thus, we set out to directly test the effects of the HIV protease inhibitors on the proteolytic activity of purified ZMPSTE24.

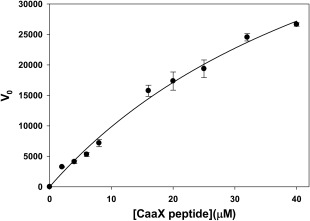

Human ZMPSTE24 purified from yeast exhibited activity against the farnesylated fluorogenic substrate based on the CaaX sequence of human K‐Ras that had previously been used to assay activities of yeast Ste24p.17, 29 This peptide is subject to preferential cleavage by Ste24p over the alternative CaaX protease Rce1p.29 As expected, based on the interchangeability of human and yeast Ste24 enzymes, the K‐Ras peptide was cleaved by purified ZMPSTE24 in a reaction characterized by a K m of approximately 60 µM with K cat ≈ 1 sec−1 (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Kinetics of proteolysis by purified ZMPSTE24. Initial velocity, assayed based on cleavage of fluorogenic prenylated peptide is displayed arbitrary fluorescent units. Nonlinear least squares fitting to the data yielded an estimate of the K m of 57 ± 12 µM as described in the text.

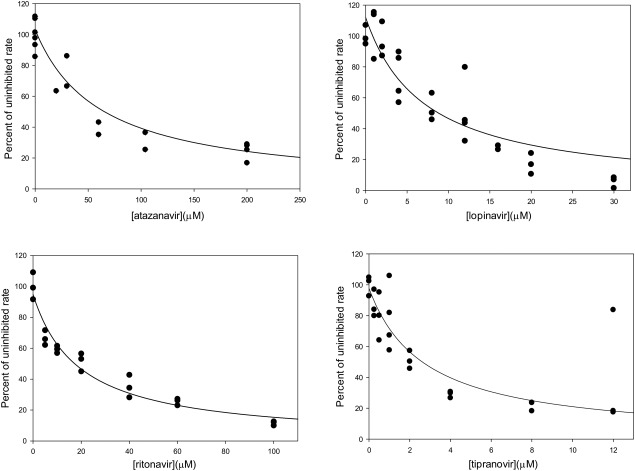

The activity of the purified ZMPSTE24 was inhibited by the tested HIV protease inhibitors to varying extents characterized by K i s ranging from 2 μM to greater than 50 μM (Table 2, Fig. 9). The inhibition constants correspond approximately to those seen using the coupled proteolysis/methylation assay for crude membranes expressing mouse ZMPSTE24,13, 14 but are lower than those observed using the same assay for purified yeast Ste24p, suggesting that the previously‐observed differences were due to difference between the yeast and human enzymes, rather than the application of the assay to the crude membrane fraction.

Table 2.

Inhibition of ZMPSTE24 by Protease Inhibitors

| Kia | V max a, b | Peptide concentration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atazanavir | 49 ± 13 μM | 46,000 ± 3,000 | 16 μM |

| Darunavir | >50 µM | N.D.c | 16 µM |

| Lopinavir | 5.6 ± 1.1 µM | 64,900 ± 400 | 16 μM |

| Ritanovir | 15 ± 2 µM | 65,000 ± 5,000 | 16 μM |

| Tipranovir | 2.2 ± 0.6 µM | 86,300 ± 6,000 | 16 µM |

Estimated Ki and V max were obtained from fit to rates for competitive Michaelis Menten enzyme inhibition V = V m*S/(K m +(K m [I]/K i)+[S]) where V m is the V max of the enzyme, K m is the Michaelis constant of the enzyme, [I] is the inhibitor concentration, K i is the inhibition constant, and [S] is the substrate concentration. Error estimates are based on standard error of the least squares fit to the data.

V max is presented in relative fluorescent units corrected for ZMPSTE24 concentration. The listed values refer to the uninhibited V max values derived from fitting.

No inhibition was detected at concentrations up to 50 µM darunavir.

Figure 9.

Inhibition of the activity of purified ZMPSTE24 activity by HIV protease inhibitors. Activity in the presence indicated concentrations of (a) atazanavir, (b) lopinavir, (c) ritanovir, and (d) tipranovir is presented as a fraction of activity in the absence of inhibitor. Inhibition constants derived from the indicated nonlinear least squares fits based on a competitive inhibition model are listed in Table II.

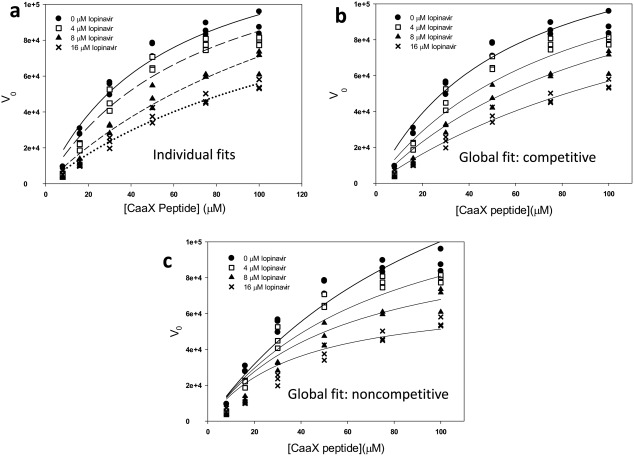

Considering the many differences between ZMPSTE24 and HIV protease, including differences in catalytic residues (aspartic acid protease vs. zinc metalloprotease) and the geometries of the respective active sites, it was of interest to attempt to determine the mode of inhibition of the inhibitors on ZMPSTE24. The kinetics of the reaction at different substrate concentrations in the presence of increasing concentrations of lopinavir [Fig. 10(A), Table 3] were fit to Michaelis‐Menten kinetics, yielding an increasing apparent K m with increasing inhibitor concentrations, and a relatively unchanged V max. This is a hallmark of competitive inhibition.30 In addition, the data were subjected to global least squares fitting to either a competitive [Fig. 10(B)] or noncompetitive [Fig. 10(C)] models of inhibition. As is evident from inspection of Figure 10, despite having the same number of degrees of freedom, the competitive model exhibited a better fit to the data than the noncompetitive model based on a greater r 2 value for the global fit (0.96 for competitive vs. 0.93 for noncompetitive) and a smaller absolute sum of the squares (60% of the noncompetitive value). We conducted preliminary experiments indicative of direct binding of inhibitors to purified ZMPSTE24, as would be expected for a competitive mode of inhibition, however efforts to characterize and quantitate such binding were hampered by the low solubility of the inhibitors, by the relatively low affinity of the interactions, and by the complications inherent in assaying binding of a nonpolar ligand to a detergent‐solubilized membrane protein.

Figure 10.

Individual and global analysis of inhibition of purified ZMPSTE24 by lopinavir. Activity was assayed in the presence of the indicated substrate and inhibitor concentrations. The same experimental data is displayed in all three panels. The concentration of ZMPSTE24 was 60 nM. (a) Individual fits to Michaelis Menten kinetics of ZMPSTE24 activity in the presence of four different concentrations of lopinavir (see Table III). (b) Global fit of competitive inhibition model to ZMPSTE24 activity. Parameters derived from the fit are displayed in Table III. (c) Global fit of noncompetitive inhibition model to ZMPSTE24 activity.

Table 3.

Kinetic Analysis of Lopinavir Inhibition of ZMPSTE24 Derived From Individual and Global Fitting

| Concentration of lopinavir (µM) | Apparent K m (µM) | V max (relative units) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 56 ± 11 | 148,000 ± 14,000 |

| 4 | 73 ± 18 | 148,000 ± 20,000 |

| 8 | 160 ± 50 | 181,000 ± 42,000 |

| 16 | 140 ± 30 | 137,000 ± 21,000 |

| (global fit: competitive) | 57 ± 8 | 150,000 ± 10,000 |

Discussion

We report here the purification of ZMPSTE24, the human transmembrane CaaX protease following expression in bakers’ yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Contrary to expectations, codon optimization of the human gene allowed expression in yeast at levels comparable to those achieved for the native yeast Ste24p, yielding purified protein with reduced tendency to aggregate and precipitate compared to the yeast enzyme. Furthermore, crystals grown under conditions similar to those used to crystallize the yeast protein diffracted to higher resolution than had been achieved for the yeast protein. The yeast‐expressed ZMPSTE24 crystals also diffracted to higher resolution and adopted different crystal packing compared to previously reported crystals of human ZMPSTE24 purified from an insect cell expression system.

The higher resolution X‐ray structure provides several new pieces of information relevant to understanding the function of the unusually large internal cavity in Ste24 proteins. A previously‐noted opening between the internal cavity and the presumed lipid‐facing exterior is more prominent in the current structure. The increased area of the opening arises from displacement of transmembrane segment TM5, compared with previous structure and may also result partially from the fact that sequences adjacent to TM5 and TM6 are missing from the current structure, presumably due to disorder. Such disorder, and the structural displacements compared to the previous structures could be part of gating mechanisms controlling entry and egress of substrates to and from the internal catalytic site. The presence of a lipid‐ or detergent‐like density traversing this large opening suggests that this might provide the route by which the farnesyl group on prelamin A penetrates the protein barrier. Other similar densities seen protruding through smaller fenestrations in the current structure indicate that these may be hydrophobic openings that are normally filled by lipids.

The resolution of the current structure allowed identification of densities indicative of the presence of a large number of ordered water molecules inside the internal cavities, including ordered water involved in nearly tetrahedral coordination of the active site zinc atom. The positions of the waters in the active site differ somewhat from those seen in some structures of the related zinc metalloprotease thermolysin, suggesting that the proteolytic activity can accommodate some flexibility in the exact geometry of these positions. In fact, considerable variation is seen in the geometries of waters close to the zinc atom in comparing various previous structures of thermolysin. The co‐linear arrangement of the two water molecules closest to the zinc atom of ZMPSTE24 raises the possibility that this provides a pathway for repeated introduction of water into the active site for consumption in multiple rounds of the hydrolysis reaction. Aside from its likely direct role in proteolysis, the presence of water inside the cavity of ZMPSTE24 may constitute a store that is necessary for repeated proteolytic cleavages and also may provide a mechanism for insulating bound substrates from directly interacting with internal‐facing groups of ZMPSTE24. Such insulation may be necessary to accommodate the multiple specificities of this enzyme, allowing it to cleave two distinct sites in prelamin A as well as in the precursor to yeast a‐factor.31, 32 Such relaxed specificity of cleavage may also be important for the proposed role of ZMPSTE24 in cleavage of proteins that are incompletely translocated in the endoplasmic reticulum.33

Using ZMPSTE24 purified from yeast, we demonstrated that HIV protease inhibitors directly inhibit the proteolytic activity of the detergent‐solubilized purified enzyme, thereby ruling out the possibility that these drugs act indirectly to inhibit CaaX protease activity through some additional component of the membrane fractions used previously or through some effect on coupling to the carboxylmethylation step used as a readout in previous assays of inhibition. The inhibition constants characterizing the interactions of the drugs with purified ZMPSTE24 are consistent with those observed in previous assays, including the rank ordering of inhibition by the different available inhibitors. The concentrations of drugs required to achieve effective inhibition are well within the ranges observed in serum and cells in patients receiving these therapies,27 thus the unintended effects of these inhibitors on ZMPSTE24 must be considered in seeking explanations for the well‐documented side‐effects of the therapies, such as lipodystrophy. Kinetic assays of the effects of these drugs on purified ZMPSTE24 are consistent with a competitive mode of inhibition, raising the intriguing question of how drugs designed to specifically inhibit an aspartyl protease with a very different class of substrates compared with those of ZMPSTE24 can competitively interact with the zinc‐containing active site of ZMPSTE24. Although the best‐diffracting crystals of ZMPSTE24 were prepared in the presence of concentrations of the inhibitor lopinavir considerably higher than the observed inhibition constants, no density clearly corresponding to the inhibitor was observed in the refined structure. Furthermore, no evidence for uniform binding of inhibitor was obtained from difference maps comparing diffraction from crystals containing or lacking lopinavir or tipranovir. Thus, either the inhibitors do not bind in a well‐defined single configuration or the conditions used for crystallization diminish binding of the inhibitors compared to the conditions used for assays of ZMPSTE24 activity.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

HIV protease inhibitors tipranavir (Cat. # 11285), darunavir (Cat. #11447), lopinavir (Cat. # 9481), azatanavir (Cat. # 10003) and ritonavir (Cat. # 4622) were obtained from the NIH AIDS Reagent Program. Lopinavir was also purchased from SigmaAldrich (Cat. # Y0001498). Heptaethyleneglycol mono n‐dodecyl ether (C12E7 detergent) and n‐dodecyl‐β‐maltoside were purchased from Nikko Chemicals Company Ltd., Japan and Glycon Biochemical GmbH, Germany, respectively. Farnesylated peptide, (AbzK)SKTKC(farnesyl)VIQL, was purchased from AnaSpec, Inc.

ZMPSTE24 expression construct

The human ZMPSTE24 ORF was codon‐optimized for expression in S. cerevisiae and synthesized by Genewiz. The gene was then PCR amplified and inserted into vector pSGP46 via ligation independent cloning, as described previously.20 In this vector the cloned gene is under control of the ADH2 promoter and is fused to C‐terminal IgG‐binding (ZZ) and His10 tags, both cleavable by rhinovirus 3C protease. For protein expression, the insert‐containing plasmids was transformed into S. cerevisiae strain BJ5460 (ATCC 208285) (MAT a ura3‐52 trp1 lys2‐801 leu2‐Δ1 his3‐Δ200 pep4::HIS3 prb1‐Δ1.6R can1 GAL+) to create yeast strain YO1362. The optimized ZMPSTE24 gene is missing the codon for the normal C‐terminal histidine.

Protein purification

Protein expression and purification followed the general procedures described previously for the yeast ortholog of ZMPSTE24, Ste24p from Saccharomyces mikatae.17, 20 Specifically, six 1.8 L cultures of SD‐ura medium were each inoculated with 100 mL of an overnight growth of strain YO1362. These cultures were incubated in 4 L flasks at 30°C while shaking at 230 rpm until they reached an OD600 of 2.0. The cells from each culture were centrifuged at 4000 × g for 10 min at 4°C; the pellets were pooled and used to inoculate 9 L of YPD medium. Further growth was conducted in a BioFlo3000 fermenter (New Brunswick Scientific) at 26°C with agitation at 400 rpm. Cells were harvested 24 h after induction of protein expression (OD600 ∼14; wet pellet weight ∼300 g); protein expression under the control of the ADH2 promoter is induced after glucose depletion from the medium. Cells were stored frozen at −80°C. After thawing at 4°C, pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 15% (w/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 100 µM PMSF) at ∼1 g (wet weight)/mL. The cells were lysed by two passes at ∼25,000 psi through an Avestin C‐3 homogenizer with the outlet cooling coil immersed in an ice bath. Lysate was centrifuged at 4000 × g for 12 min at 4°C. The pellets from this spin were resuspended in a total of 150 mL of lysis buffer, subjected to one additional pass through the homogenizer (under the same conditions as the previous passes), then centrifuged again at 4000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Membranes were isolated from the supernatant by centrifugation at 120,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C. The membrane pellets (∼33 g) were resuspended in buffer (20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 15% (w/v) glycerol, 100 µM PMSF, 1 mM DTT) at 7 mL/g using a hand‐held homogenizer (VWR Power Max) at lowest power, to prevent foaming. Membranes were solubilized by adding 20% (w/v in water) n‐dodecyl‐β‐d‐maltopyranoside to a final detergent concentration of 1.5% (w/v) and by incubation at room temperature for 90 min on a roller‐mixer (Stuart, SRT6D). Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 4000g for 20 min at 4°C.

The C‐terminal IgG binding tag was used in affinity purification. The remaining steps were all performed at 4°C. The solubilized membranes were incubated for 4 h on a roller/mixer with 8 mL (packed resin) of IgG Sepharose 6 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) that had been pre‐equilibrated with buffer containing 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 15% (w/v) glycerol, and 0.01% (w/v) DDM. The IgG Sepharose was then washed four times by centrifugation at 700 × g, 3 min. with 30 resin volumes (each) of wash buffer consisting of 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 15% (w/v) glycerol, 0.04% C12E7, 100 µM PMSF, and 1 mM DTT. ZMPSTE24 was removed from the IgG Sepharose by cleavage of the tag using rhinovirus 3C protease. One resin volume of the wash buffer containing 0.04% C12E7 and 3.5 mg rhinovirus 3C protease tagged with an N‐terminal His6 tag34 was incubated with the IgG Sepharose overnight then the cleaved ZMPSTE24 was separated from the IgG Sepharose resin by filtration using a 50 mL tube‐top 0.22 µm cellulose acetate filter (Corning). The tagged 3C protease was then removed by incubation of the filtrate for 2 h with 2 mL of nickel affinity resin (Roche cOmplete His‐Tag Purification Resin) that had been pre‐equilibrated with the wash buffer containing 0.04% C12E7. The ZMPSTE24 was separated from the affinity resin and bound protease using filtration as above. The protein was concentrated to 5 mL using a 50 kDa cutoff regenerated cellulose centrifugal concentrator (Millipore) and then additionally purified by size exclusion chromatography using a GE Healthcare HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 column (120 mL bed volume) that had been pre‐equilibrated with a buffer consisting of 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 5% (w/v) glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 0.04% C12E7, and 1 mM DTT; the protein was eluted with the same buffer at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. ZMPSTE24‐containing protein fractions from the peak shown in Figure 2 were combined and analyzed prior to being concentrated and set up for crystallization experiments immediately. An additional peak eluting near the void volume of the column was typically observed to contain ZMPSTE24 and additional proteins and to represent approximately half the amount of protein (based on absorbance at 280 nm) recovered in the collected peak. A 9‐liter yeast culture yielded ∼6 mg of purified ZMPSTE24.

Crystallization of ZMPSTE24

Initial crystal screening was conducted using Molecular Dimensions’ Morpheus®, MemGold™, and MemGold2™ screens.35, 36 Sitting‐drop vapor diffusion experiments were set up using a Mosquito nanoliter‐scale robot (TTP LabTech) with 70 nl each protein and precipitant. Prior to the addition of crystallization reagents, ZMPSTE24 protein was concentrated to 7.0 mg/mL using an Amicon Ultracel 50 kDa MW cutoff centrifugal concentrator (Millipore). Trays were set up at 13°C and 4°C. Crystals grew as thin rods measuring 50–400 µm long and 10–20 µM wide after approximately 24 h at 13°C under multiple crystallization conditions; plates set up at 4°C showed no crystal growth. For optimization, both sitting and hanging drop vapor diffusion trials were done at protein to cocktail ratios of 1:1 and 2:1. Crystals grown at 13°C diffracted to around 2.8–3.2 Å. The best diffracting crystals (2.0–2.5 Å) were grown for 12 h at 13°C to initiate nucleation and then transferred to 4°C for growth under sitting drop conditions (1:1). Cocktail components were 24% PEG 3350, 170 mM ammonium sulfate, 15% glycerol, and 50 mM Hepes pH 7.5 with lopinavir or tipranovir at 150 µM. Lopinavir solubilized in a 50:50 mixture of dimethylsulfoxide and 1,4‐dioxane or tipranovir solubilized in DMSO was added to the protein, mixed, and incubated for 1 h at 4°C prior to the addition of crystallization cocktails. Crystals were harvested without additional cryoprotection.

X‐ray data collection and analysis

Initial screening of crystals was performed using the GM/CA CAT beamline 23‐ID‐D of the Advanced Photon Source (APS) of Argonne National Laboratory. Data collection for structural analyses was performed remotely at NECAT beamline 24‐ID‐C at APS using a wavelength of 0.9791 Å and a beam size of 20 μm. Indexing and integration of diffraction data were performed using iMosflm37 and further analyzed using the program Aimless38 of the CCP4 program suite.39 Datasets were scaled and merged using the program Blend.21 Phasing was accomplished by molecular replacement using the Phaser module of the Phenix program suite40 based on the previously‐solved structure of ZMPSTE24 (PDB code: 4AW6).18 Refinement of the structure was performed using Phenix with manual operations performed using Coot.41 Further analysis of the refined structure was performed using PDB Redo.42 Figures were prepared using PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Schrödinger, LLC).

Assay of ZMPSTE24 activity

The activity of purified ZMPSTE24 in cleaving a C‐terminal CaaX sequence was determined using a fluorescence‐based assay previously developed for the investigation of substrate specificity of yeast Ras converting enzyme (Rce1p) and Ste24p in membrane fractions.17, 29 The procedure uses the peptide sequence (AbzK)SKTKC(farnesyl)VIQL, where AbzK refers to an aminobenzoic acid derivative of lysine and QL refers to an ε‐dinitrophenyl derivative of lysine, that was found to be optimal for assaying Ste24p activity. In the intact peptide, the dinitrophenyl group quenches the fluorescence of the aminobenzoic acid; cleavage at the C‐terminal side of the farnesylated cysteine releases the quenching group and results in an increase in fluorescence. The peptide substrate was diluted from a 1 mM stock solution in 2.6% DMSO to a final concentration of 0.1 mM in 100 mM Hepes pH 7.5 just prior to performing the assay. Because of detergent effects on the peptide substrate (indicated by effects on peptide fluorescence in the absence of enzyme), it was necessary to conduct the assays at a lower C12E7 concentration (0.005%) than was used in purifying ZMPSTE24 (0.04%) by diluting the purified protein into the lower detergent concentration immediately prior to performing the assay. To initiate the assay, the protein stock was diluted into reaction buffer (100 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM (0.005%) C12E7) to a final concentration of 30 nM and equilibrated at room temperature for 1 minute. The peptide substrate was then added to the diluted ZMPSTE24 to the concentrations required for the assay, thoroughly mixed, and then transferred to the fluorimeter (Horiba Jobin Yvon Fluoromax®‐4). The sample was equilibrated in the fluorimeter for 1 minute before the initial change in fluorescence intensity was recorded. The excitation wavelength was 320 nm; fluorescence emission was detected at 415 nm using an integration time of 1 sec and slit widths corresponding to 5 nm. Reaction temperature was maintained at 25°C with a recirculating bath. Neither substrate nor ZMPSTE24 incubated alone exhibited any significant change in fluorescence over the time period of the assay. Measurements were taken every ten seconds for 2 min. with the fluorimeter in anti‐bleaching mode. Protein concentrations were determined by SDS PAGE analysis using BSA protein as standard and UV (280 nm) spectroscopy using calculated extinction coefficients.

The K m of the reaction was fit to the measured initial velocities using the non‐linear least squares algorithm in Sigmaplot (Systat Software Inc.). (Limitations on the solubility and availability of peptide precluded measurements at substrate concentrations higher than the apparent K m.) An approximate conversion between the observed fluorescence intensity changes and substrate conversion on a molar basis was established based on the total fluorescence change of peptide substrate during long reactions with purified enzyme that allow for nearly complete conversion of the known concentrations of substrate to product. The final fluorescence of such reactions was quantitated by fitting an exponential rise to the time course of the fluorescence change.

Inhibition of ZMPSTE24 by five HIV protease inhibitors, tipanavir, lopinavir, ritonavir, atazanavir, and darunavir, was investigated. The protease inhibitors, which have limited solubilities in water, were initially solubilized in DMSO. Stock concentrations of inhibitors were adjusted such that the DMSO concentration in the sample was constant at 0.6%. To perform the assay, the protein stock was diluted into reaction buffer (100 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM (0.005%) C12E7) to a final concentration of 30 nM or 60 nM. Unless otherwise indicated in the figures, the concentration of fluorogenic substrate was 16 µM. Inhibitor was then added and the mix was incubated for 1 min, then substrate was added and mixed. Samples were equilibrated in the fluorimeter for 1 min. before the initial change in fluorescence intensity was recorded as described above.

Inhibition constants and an estimated V max value (which can vary with individual enzyme preparations and assay conditions) for each particular assay were derived by fitting to the expression for competitive Michaelis Menten enzyme inhibition V = V m*S/(K m + (K m [I]/K i)+[S]) where V m is the V max of the enzyme, K m is the Michaelis constant of the enzyme, [I] is the inhibitor concentration, K i is the inhibition constant, and [S] is the substrate concentration. Where indicated, a global fit of competition in the presence of various concentrations of substrate and inhibitor was analyzed based on this expression using GraphPad Prism version 4.02 for Windows, (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA).

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Joseph Wedekind and Michael Malkowski for helpful discussions. They also thank the staffs of the APS NECAT and GM/CA beamlines for assistance. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Statement: We report the structure (to 2.0 Å resolution) of yeast‐expressed human transmembrane CaaX protease ZMPSTE24 responsible for dual proteolytic cleavages of nuclear prelamin A subsequent to farnesylation. This allowed identification of features of the catalytic site, the nature of the large internal cavity, and routes of access to the active site in the cavity. We also show that HIV protease inhibitors used in antiviral therapy directly inhibit the purified human enzyme.

Data Deposition: The ZMPSTE24 structure has been deposited in the Protein Database (accession code: 5SYT).

Crystallographic studies described in this manuscript made use of structural biology services at the University of Rochester supported by NIH grants S10 RR026501 and P30 AI078498. Crystallographic data collection was conducted at the Advanced Photon Source beamlines of the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team funded by NIH grants P41 GM103403 and S10 RR029205 and of GM/CA@APS, funded in whole or in part with funds from the National Cancer Institute (ACB‐12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM‐12006). The Advanced Photon Source is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE‐AC02‐06CH11357.

References

- 1. Kho Y, Kim SC, Jiang C, Barma D, Kwon SW, Cheng J, Jaunbergs J, Weinbaum C, Tamanoi F, Falck J, Zhao Y (2004) A tagging‐via‐substrate technology for detection and proteomics of farnesylated proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:12479–12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Onono FO, Morgan MA, Spielmann HP, Andres DA, Subramanian T, Ganser A, Reuter CW (2010) A tagging‐via‐substrate approach to detect the farnesylated proteome using two‐dimensional electrophoresis coupled with Western blotting. Mol Cell Proteomics 9:742–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barrowman J, Michaelis S (2009) ZMPSTE24, an integral membrane zinc metalloprotease with a connection to progeroid disorders. Biol Chem 390:761–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pendas AM, Zhou Z, Cadinanos J, Freije JM, Wang J, Hultenby K, Astudillo A, Wernerson A, Rodriguez F, Tryggvason K, Lopez‐Otin C (2002) Defective prelamin A processing and muscular and adipocyte alterations in Zmpste24 metalloproteinase‐deficient mice. Nat Genet 31:94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Agarwal AK, Fryns JP, Auchus RJ, Garg A (2003) Zinc metalloproteinase, ZMPSTE24, is mutated in mandibuloacral dysplasia. Hum Mol Genet 12:1995–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eriksson M, Brown WT, Gordon LB, Glynn MW, Singer J, Scott L, Erdos MR, Robbins CM, Moses TY, Berglund P, Dutra A, Pak E, Durkin S, Csoka AB, Boehnke M, Glover TW, Collins FS (2003) Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson‐Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature 423:293–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fong LG, Ng JK, Meta M, Cote N, Yang SH, Stewart CL, Sullivan T, Burghardt A, Majumdar S, Reue K, Bergo MO, Young SG (2004) Heterozygosity for Lmna deficiency eliminates the progeria‐like phenotypes in Zmpste24‐deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:18111–18116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gordon LB, Kleinman ME, Miller DT, Neuberg DS, Giobbie‐Hurder A, Gerhard‐Herman M, Smoot LB, Gordon CM, Cleveland R, Snyder BD, Fligor B, Bishop WR, Statkevich P, Regen A, Sonis A, Riley S, Ploski C, Correia A, Quinn N, Ullrich NJ, Nazarian A, Liang MG, Huh SY, Schwartzman A, Kieran MW (2012) Clinical trial of a farnesyltransferase inhibitor in children with Hutchinson‐Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:16666–16671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Capell BC, Olive M, Erdos MR, Cao K, Faddah DA, Tavarez UL, Conneely KN, Qu X, San H, Ganesh SK, Chen X, Avallone H, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R, Nabel EG, Collins FS (2008) A farnesyltransferase inhibitor prevents both the onset and late progression of cardiovascular disease in a progeria mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:15902–15907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scaffidi P, Misteli T (2006) Lamin A‐dependent nuclear defects in human aging. Science 312:1059–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McClintock D, Ratner D, Lokuge M, Owens DM, Gordon LB, Collins FS, Djabali K (2007) The mutant form of lamin A that causes Hutchinson‐Gilford progeria is a biomarker of cellular aging in human skin. PLoS One 2:e1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rodriguez S, Coppede F, Sagelius H, Eriksson M (2009) Increased expression of the Hutchinson‐Gilford progeria syndrome truncated lamin A transcript during cell aging. Eur J Hum Genet 17:928–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coffinier C, Hudon SE, Farber EA, Chang SY, Hrycyna CA, Young SG, Fong LG (2007) HIV protease inhibitors block the zinc metalloproteinase ZMPSTE24 and lead to an accumulation of prelamin A in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:13432–13437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coffinier C, Hudon SE, Lee R, Farber EA, Nobumori C, Miner JH, Andres DA, Spielmann HP, Hrycyna CA, Fong LG, Young SG (2008) A potent HIV protease inhibitor, darunavir, does not inhibit ZMPSTE24 or lead to an accumulation of farnesyl‐prelamin A in cells. J Biol Chem 283:9797–9804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Caron M, Auclair M, Donadille B, Bereziat V, Guerci B, Laville M, Narbonne H, Bodemer C, Lascols O, Capeau J, Vigouroux C (2007) Human lipodystrophies linked to mutations in A‐type lamins and to HIV protease inhibitor therapy are both associated with prelamin A accumulation, oxidative stress and premature cellular senescence. Cell Death Differ 14:1759–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garg A (2011) Clinical review: lipodystrophies: genetic and acquired body fat disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:3313–3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pryor EE, Jr , Horanyi PS, Clark KM, Fedoriw N, Connelly SM, Koszelak‐Rosenblum M, Zhu G, Malkowski MG, Wiener MC, Dumont ME (2013) Structure of the integral membrane protein CAAX protease Ste24p. Science 339:1600–1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Quigley A, Dong YY, Pike AC, Dong L, Shrestha L, Berridge G, Stansfeld PJ, Sansom MS, Edwards AM, Bountra C, von Delft F, Bullock AN, Burgess‐Brown NA, Carpenter EP (2013) The structural basis of ZMPSTE24‐dependent laminopathies. Science 339:1604–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen P, Sapperstein SK, Choi JD, Michaelis S (1997) Biogenesis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mating pheromone a‐factor. J Cell Biol 136:251–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clark KM, Fedoriw N, Robinson K, Connelly SM, Randles J, Malkowski MG, DeTitta GT, Dumont ME (2010) Purification of transmembrane proteins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae for X‐ray crystallography. Protein Expr Purif 71:207–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Foadi J, Aller P, Alguel Y, Cameron A, Axford D, Owen RL, Armour W, Waterman DG, Iwata S, Evans G (2013) Clustering procedures for the optimal selection of data sets from multiple crystals in macromolecular crystallography. Acta Cryst D69:1617–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holland DR, Tronrud DE, Pley HW, Flaherty KM, Stark W, Jansonius JN, McKay DB, Matthews BW (1992) Structural comparison suggests that thermolysin and related neutral proteases undergo hinge‐bending motion during catalysis. Biochemistry 31:11310–11316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matthews BW (1988) Structural basis of the action of thermolysin and related zinc peptidases. Acc Chem Res 21:333–340. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Holland DR, Hausrath AC, Juers D, Matthews BW (1995) Structural analysis of zinc substitutions in the active site of thermolysin. Protein Sci 4:1955–1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barrowman J, Wiley PA, Hudon‐Miller SE, Hrycyna CA, Michaelis S (2012) Human ZMPSTE24 disease mutations: residual proteolytic activity correlates with disease severity. Hum Mol Genet 21:4084–4093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Caron M, Auclair M, Sterlingot H, Kornprobst M, Capeau J (2003) Some HIV protease inhibitors alter lamin A/C maturation and stability, SREBP‐1 nuclear localization and adipocyte differentiation. AIDS 17:2437–2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leon A, Martinez E, Sarasa M, Lopez Y, Mallolas J, De Lazzari E, Laguno M, Milincovic A, Blanco JL, Larrousse M, Lonca M, Gatell JM (2007) Impact of steady‐state lopinavir plasma levels on plasma lipids and body composition after 24 weeks of lopinavir/ritonavir‐containing therapy free of thymidine analogues. J Antimicrob Chemother 60:824–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hudon SE, Coffinier C, Michaelis S, Fong LG, Young SG, Hrycyna CA (2008) HIV‐protease inhibitors block the enzymatic activity of purified Ste24p. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 374:365–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Porter SB, Hildebrandt ER, Breevoort SR, Mokry DZ, Dore TM, Schmidt WK (2007) Inhibition of the CaaX proteases Rce1p and Ste24p by peptidyl (acyloxy)methyl ketones. Biochim Biophys Acta 1773:853–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lorsch JR (2014) Practical steady‐state enzyme kinetics. Methods Enzymol 536:3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tam A, Nouvet FJ, Fujimura‐Kamada K, Slunt H, Sisodia SS, Michaelis S (1998) Dual roles for Ste24p in yeast a‐factor maturation: NH2‐terminal proteolysis and COOH‐terminal CAAX processing. J Cell Biol 142:635–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schmidt WK, Tam A, Michaelis S (2000) Reconstitution of the Ste24p‐dependent N‐terminal proteolytic step in yeast a‐factor biogenesis. J Biol Chem 275:6227–6233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ast T, Michaelis S, Schuldiner M (2016) The protease Ste24 clears clogged translocons. Cell 164:103–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alexandrov A, Vignali M, LaCount DJ, Quartley E, de Vries C, De Rosa D, Babulski J, Mitchell SF, Schoenfeld LW, Fields S, Hol WG, Dumont ME, Phizicky EM, Grayhack EJ (2004) A facile method for high‐throughput co‐expression of protein pairs. Mol Cell Proteomics 3:934–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gorrec F (2009) The MORPHEUS protein crystallization screen. J Appl Cryst 42:1035–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Parker JL, Newstead S (2012) Current trends in alpha‐helical membrane protein crystallization: an update. Protein Sci 21:1358–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Battye TG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AG (2011) iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction‐image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Cryst D67:271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Evans PR, Murshudov GN (2013) How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Cryst D69:1204–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Cryst D67:235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse‐Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python‐based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Cryst D66:213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Cryst D66:486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Joosten RP, Long F, Murshudov GN, Perrakis A (2014) The PDB_REDO server for macromolecular structure model optimization. IUCr J 1:213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information