We will meet in the developing world a level of will, skill, and constancy that may put ours to shame. We may find ourselves not the teachers we thought we were, but students of those who work under circumstances that would have stopped us long ago.1

The idea of a BMJ issue focusing on what rich countries can learn from poorer ones came from our editorial board. Western medical journals' coverage of health issues in low income countries is “limited and negative,” they said. As a result they don't capture the learning potential of successful health initiatives developed in countries long honed to making the best of meagre resources.

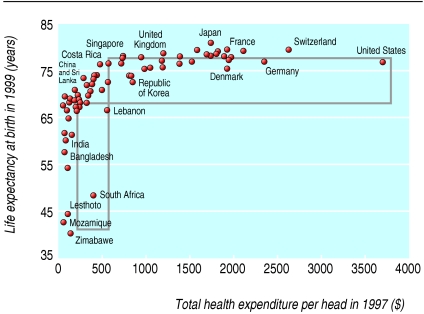

Challenged to do better, the BMJ set up a team of advisers, put out a call for examples, and solicited ideas via global research networks and email discussion lists including AFRO-NETS and HIF-net at the World Health Organization. This issue reflects a variety of views of what high income countries whose increasing investment in health pays uncertain dividends (figure) can learn from poorer ones—and what poorer ones can learn from each other.

Figure 1.

The relation between expenditure on health and outcome, here in relation to longevity, is tenuous (adapted from the UC Atlas of Global Inequality)

Cynics may argue that the whole concept of learning from the “developing countries” is an exercise in semantics. What matters is not where you live but how poor you are, whether it is Tower Hamlets in London or Kiberia in Nairobi. Geography is no protection from the diseases of poverty, which WHO recognises as a disease category on its own.

Diseases currently prevalent in countries where people live on less than a dollar a day were common in Europe in the 18th century.2 Death rates declined between 1700 and 1925 owing to improved living conditions, clean water supplies, safe sanitation, and better nutrition and hygiene—not medical interventions.3

Most people in low income countries live in abject poverty. Health inequalities widen, health systems are often dysfunctional, and serious epidemics such as HIV/AIDS and malaria are coupled with increasing insecurity.4 Despite this there are notable examples of success—new cases of HIV/AIDS in Uganda have declined, and measles has been controlled in Brazil.5,6 What these show is that political will and emphasis on evidence based interventions make a difference.

Drawing on the experience of the successful Carbayllo tuberculosis project in Peru and quality improvement initiatives in Russia, Berwick reminds us of the importance of keeping interventions simple, spreading in stages, building good information systems, and taking teams seriously.1

Costello emphasises the wide potential of community programmes mediated through local women's groups in Nepal and rural India, which have resulted in impressive reductions in maternal and neonatal mortality rates (p 1166). The Tanzanian Essential Health Project illustrates how cost effective interventions can be when locally led (p 1126).

Describing initiatives is not difficult. Analysing the reasons for their success and identifying the transferable components is harder as commentaries on containing drug costs in rich countries (p 1172) and providing community mental health services (p 1140) underline. But the potential exists. Iran's national thalassaemia screening programme, which owes it success to good organisation and to sensitive responses to the priorities and values of affected populations, provides generic lessons for all countries (p 1115).

We need a better understanding of why some initiatives flourish while others fail—what Marsh, at community level, terms positive deviance (p 1177). Rigorous evaluation is a prerequisite of learning lessons from both success and failure, and here the international community has little to be sanguine about.

Most so called pro poor health programmes actually increase health inequity.7 Okuonzi claims that the market reforms introduced in Uganda as a precondition of donor aid have done the same (p 1173). Roll Back Malaria is failing8—“serious money” is needed to put the programme back on course and new strategies to distribute bed nets adopted. Linking with established disease control programmes may help.9 Harris advocates the same approach to expanding HAART in Malawi (p 1163).

That health gains can stem from supporting and educating women is a clear message that emerges in several guises. Priority setting based on listening and learning from individuals and communities who with support work creatively to provide their own solutions is another. The health sector in rich countries can also learn from the achievements of non governmental organisations, and the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee is a shining example (p 1124).

Difficult circumstances and scant resources fuel innovation, and strong inspirational leadership achieves a lot as many illustrative snapshots in this issue show (p 1125). Examples of successful health advocacy also exist. The People's Health Movement is a beacon in this respect (p 1127), and input from civil society is now seen as vital in the compilation of new strategies to strengthen health systems.

One of the unspoken messages of this week's issue is that we can't learn from things we don't hear about. The global conversation on health needs to be more equitable and extend beyond the health sector (p 1189). New initiatives are needed to give low income countries a stronger voice and better access to reliable relevant information.10

A final and important message health professionals and policy makers in rich countries can learn from observation of poorer ones is the importance of acting outside the health box. Health improvement in all countries depends on a concerted effort to tackle the global forces that undermine health (p 1192). It also depends on wider recognition of the determinants of health, foremost among which are poverty and inequity. Rich countries need to honour pledges made in grand international health arenas and pay more attention to how money is spent and who benefits.

Editorial advisers to the issue are Zulfiqar Bhutta, Husein Lalji professor of paediatrics and child health, Aga Khan University, Karachi 74800, Pakistan; James Tumwine, associate professor of paediatrics and president of FAME (Forum of African Medical Editors), Makere University, Kampala, Uganda; Rashad Massoud, director, Quality and Performance Institute, University Research Co, LLC/Center for Human Services, 7200 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 600, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA; Tikki Pang, director, research policy and cooperation, World Health Organization, Avenue Appia, CH-1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland; Cesar G Victora, professor of epidemiology, Federal University of Pelotas, CP 464-96001-970 Pelotas, RS, Brazil.

Competing interests: We ask all authors for a competing interest statement. This applies to all manuscripts. We need either a statement describing the interests of all authors or a declaration: “All authors declare that the answer to the questions on your competing interest form [http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/317/7154/291/DC1] are all No and therefore have nothing to declare.”

References

- 1.Berwick DM. Lessons from developing nations on improving health care. BMJ 2004;328: 1124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. The Health of Towns. Magazine and Journal of Medical Jurisprudence 1847: 152-3.

- 3.McKeown T. The role of medicine: dream, mirage or nemesis. London: Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust, 1976.

- 4.World Bank. Better health in Africa. Washington DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, World Bank, 1994.

- 5.Amosu A. How one country began winning against HIV. http://allafrica.com/stories/printable/200311300080.html (accessed 9 Nov 2004).

- 6.Fundação Nacional de Saúde. Países latino-americanos reforçam medidas para a erradicação do sarampo, 21 May 2003. www.funasa.gov.br/not/not422.htm (accessed 9 Nov 2004).

- 7.Gwatkin DR, Bhuiya A, Victora C. Making health systems more equitable. Lancet 2004;364: 1273-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamey G. Roll Back Malaria: a failing global health campaign. BMJ 2004;328: 1086-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molyneaux DH, Nantulya VM. Linking disease control programmes in rural Africa: a pro-poor strategy to reach Abuja targets and millennium development goals. BMJ 2004;328: 1129-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godlee F, Pakenham-Walsh N, Ncayiyana D, Cohen B, Packer A. Can we achieve health information for all by 2015? Lancet 2004;364: 295-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]