Abstract

While nanoparticle vaccine technology is gaining interest due to the success of vaccines like those for the human papillomavirus that is based on viral capsid nanoparticles, little information is available on the disassembly and reassembly of viral surface glycoprotein-based nanoparticles. One such particle is the hepatitis B virus surface antigen (sAg) that exists as nanoparticles. Here we show, using biochemical analysis coupled with electron microscopy, that sAg nanoparticle disassembly requires both reducing agent to disrupt intermolecular disulfide bonds, and detergent to disrupt hydrophobic interactions that stabilize the nanoparticle. Particles were otherwise resistant to salt and urea, suggesting the driving mechanism of particle formation involves hydrophobic interactions. We reassembled isolated sAg protein into nanoparticles by detergent removal and reassembly resulted in a wider distribution of particle diameters. Knowledge of these driving forces of nanoparticle assembly and stability should facilitate construction of epitope-displaying nanoparticles that can be used as immunogens in vaccines.

Keywords: glycoprotein nanoparticles, virus structure, vaccines, assembly, disassembly, reassembly, electron microscopy, tomography, HBV surface antigen

INTRODUCTION

Viral proteins can assemble into nano structures such as viral capsids, matrix layers, and nucleoprotein complexes (1, 2). These assemblies are the structural basis of viral shells or macromolecular containers that package viral genomes, and can serve as a scaffold for receptor-binding sites (3). Interestingly, a number of viral proteins can assemble into nanoparticle structures without genome incorporation, and these particles are non-infectious. Several studies indicate that non-infectious viral nanoparticles that display neutralizing epitopes, just like their cognate infectious virions, can serve as effective vaccines (4–7). Consequently, great interest has developed in viral nanoparticles for their capacities to display vaccine immunogens in a multivalent manner (4, 5). For example, one such nanoparticle is derived from the capsid of the human papillomavirus (HPV). Recombinant HPV nanoparticles constructed solely from the major capsid protein L1 can assemble into particles similar to the infectious virion (8). Since HPV infection is oncogenic, it is important that HPV vaccine design avoid live virus infection. HPV nanoparticles addressed this concern of avoiding live virus infection, and they were found efficacious in vaccine trials, becoming the basis of commercial HPV vaccines (5, 9). Here we focus on Hepatitis B virus (HBV) proteins that have long been an attractive platform for display of antigens due to their ease of expression and assembly (7, 10, 11). We aim to extend existing knowledge of nanoparticles as immunogen display platforms by characterizing disassembly and assembly of HBV based nanoparticles for use in design of recombinant vaccines. This work sets the stage for assembly of HBV particles displaying mixtures of recombinant immunogens, permitting new vaccine designs to be explored.

Surface antigen (sAg) is an HBV viral glycoprotein that forms an outer layer surrounding the viral nucleocapsid in mature virions (Figure 1A). Virions are 42 nm in diameter (12–14), but particles consisting of surface antigen alone have been observed to have a diameter of 22 nm and octahedral symmetry (10, 11). During infection, HBV sAg is expressed as three different proteins originating at different start codons along a single open reading frame, resulting in Large (L) Middle (M) and Small (S) surface antigen proteins (15, 16). Isoforms of sAg differ by the number of domains. S-sAg has only the S domain, while M-sAg has both a Pre-S2 and an S domain, and L-sAg has a Pre-S1 domain in addition to the Pre-S2 and S domain. In virions, S-sAg is the most abundant, and recombinant S-sAg (referred to here as sAg for simplicity) readily forms nanoparticles when expressed in a yeast system, which is the basis of the hepatitis B virus vaccine (7, 17). Originally named Australia-antigen, sAg was identified in hepatitis patient sera when particles were observed by electron microscopy (10). These particles isolated from sera were used as an early HBV vaccine (18, 19), and immunoassays of sAg were used to elucidate different antigenic subtypes (20). Recombinant expression of sAg and purification of recombinant sAg particles lead to the first vaccine based on recombinant DNA technology (7, 17, 21).

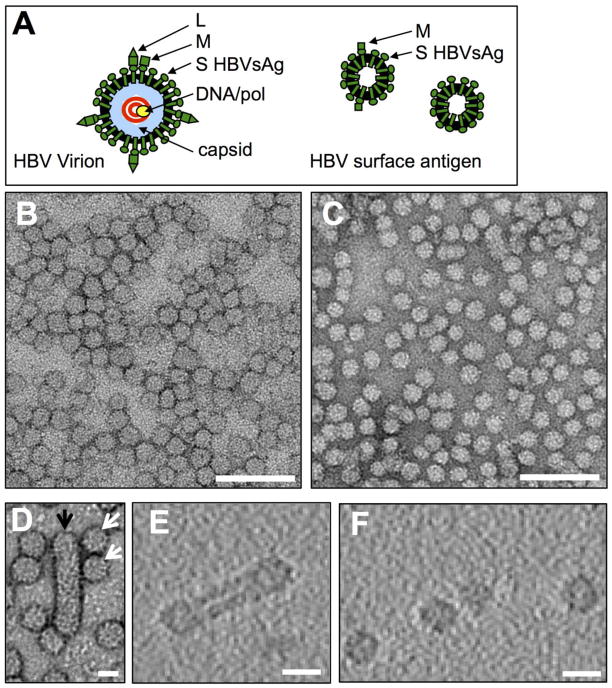

Figure 1.

Schematics of the hepatitis B virus and surface antigen (sAg) particles and electron microscopy of sAg particles from human sera. (A) Virus particle with genomic DNA (red) with viral polymerase (yellow) are encapsidated in the viral capsid (light blue). The viral glycoprotein (sAg) exists as different sizes formed with increased sizes having additional domains: Small (S), Middle (M) and Large (L). Schematic of surface antigen particles are shown dominated by the small (S) protein. (B) Image by negative-staining electron microscopy of sAg complexes purified from human serum, consisting of sAg subtype AD, or (C) sAg subtype AY. Scale bars, 100 nm. (D) A filamentous sAg particle (black arrow) is indicated among spherical particles (white arrows). (E) An x-y section through a tomographic reconstruction of a filamentous particle and (F) of a field of spherical particles from sAg subtype AD. Scale bars, 20 nm.

Due to the success of the HPV vaccine (4, 5, 9, 22), an increasing number of epitope display platforms based upon protein nanoparticles are being developed, as evidenced by promising preclinical studies of engineered nanoparticles targeting influenza, HIV, and Herpes viruses (6, 23, 24). Studies on the assembly of various viral capsid proteins from constituent molecules have been reported (8, 25–27, 41–44). However, disassembly and reassembly studies of nanoparticles from transmembrane-containing viral glycoproteins have not been studied at the level of non-membrane containing viral capsids. Even in vaccine nanoparticle systems like Chikungunya virus where viral glycoproteins can form symmetrical virus-like particles with the viral glycoprotein embedded in a membrane (28) efforts to understand this assembly in vitro have not been explored (28). One technical barrier might be optimization screening needed in working with viral membrane glycoproteins that often require specific biochemical conditions with detergents. The sAg particles seem to be an interesting system in that particles with transmembrane regions can be secreted from infected cells as nanoparticles and these particles are stable in the extracellular environment of human sera. By multivalent display of epitopes, the HBV sAg particle is immunogenic, as illustrated by development of the hepatitis B vaccine (10, 18, 45). Multivalency of other nanoparticles has been shown to confer immunogenicity to antigens displayed on the surface of designed nanoparticles (6, 23). Thus, further understanding of the interactions that drive sAg particle assembly is important to exploiting multivalency to improve antigen immunogenicity.

In this study, we defined and used biochemical disassembly reactions coupled with centrifugation and electron microscopic analysis to characterize surface antigen particles from various sources in native, unassembled and reassembled states. We found that sAg from human sera, sAg recombinantly expressed in yeast, and sAg formulated as a vaccine, all assembled into nanoparticles. Particles were predominantly spherical, consisting of a structural layer with a hollow center. The extent of disulfide cross-linking varied between sAg sources with human sAg particles being more extensively cross-linked than the yeast-derived vaccine particles. Disassembly of the particles required reduction of disulfide bonds and detergent, while reducing agent combined with salt or urea were insufficient to disassemble particles. Separation of disassembled sAg was achieved by gradient centrifugation. Disassembled sAg was reassembled into nanoparticles by removal of detergent. This suggested that hydrophobic interactions were the basis for HBV sAg nanoparticle assembly. These results improve our understanding of the sAg nanoparticle assembly process, which can be used to construct recombinant immunogens that exploit nanoparticle formation and create novel and potent vaccines.

RESULTS

Molecular morphologies and sizes of surface antigen particles from human sera. In order to determine the presence of surface antigen (sAg) particles and the conservation of their relative sizes and morphologies, electron microscopy was used to image surface antigen preparations that were isolated from different human sera. Two different sAg subtypes, AD and AY, were selected to address if subtype differences were present. Purified HBV sAg preparations were obtained commercially (see methods). Both human sAg subtypes, AD and AY, formed particles (Figure 1B, C).

For HBV sAg subtype AD, particle morphology was either spherical or filamentous (Figure 1D, white, black arrows, respectively). The filamentous morphology was much less frequently observed, accounting for less than 1% of the total particles. Particle diameter was measured across the major and minor axes of an ellipse, fit to each particle. The longest diameter was 103.5 nm, which was from a filamentous particle with an major to minor axial ratio of 4.0, indicating the particle is four-times as long as it is wide (Figure 1D, black arrow). The population average for the axial ratio of major to minor axes was 1.14 ± 0.46, and by excluding filamentous particles (axial ratio greater than 2), the population average of the axial ratio dropped to 1.07 ± 0.06, essentially equivalent to a circle. From this survey of sAg particle structure, we conclude that filamentous particles were rare, suggesting filamentous particles represent an alternative but uncommon means of particle assembly.

Morphology of particles by tomography

To probe the interior of the particles and address the questions of whether the particles were multilayered or if the complexes had dense interiors, cryo-electron tomography was used. Regions were searched in order to image rare filamentous morphologies. Both filamentous and spherical particles were constructed of an electron dense shell that surrounded an empty cavity containing density similar to the surrounding solvent (Figure 1E, 1F). Moreover, near-central sections through the tomograms of spherical sAg particles presented ring-like structures (Figure 1F). Filamentous sAg particles appeared dumbbell-shaped in that the ends appeared slightly larger and rounder than the middle of the filament (Figure 1E). Tomography suggested that internal structure of filamentous particles was similar to spherical particles, and that the foundational structure of filamentous and spherical particles was likely very similar.

Comparison of sAg particles of AD and AY subtypes

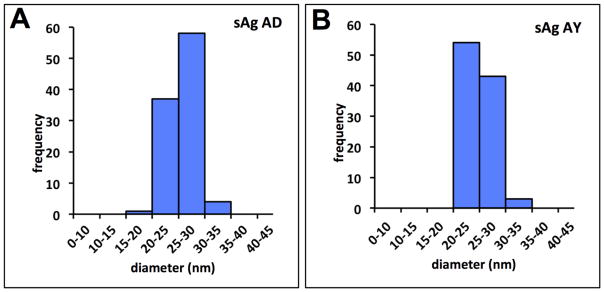

The diameters of the spherical particles for HBV sAg subtype AD varied from 20.4 nm to 30. 7 nm, but the majority of the particles was well described by the average diameter, calculated as 27.9 ± 0.4 nm. Analysis using an independently purified preparation of sAg AD with independent imaging found particle diameters ranged from 19.2 nm to 31.8 nm, and the average diameter was 25.6 ± 1.7 nm, which was in reasonable agreement with previous observations (Figure 2A). The second preparation of sAg was analyzed in parallel with sAg subtype AY for direct comparison. For particles of sAg subtype AY, the diameters ranged from 21.5 nm to 34.1 nm, and the average diameter was 25.2 ± 1.9 nm (Figure 2B). The particle diameters for the two subtypes were not significantly different. Particles had rough surfaces that had punctate-like patterns suggestive of individual protein spikes protruding from the particle (Figure 1B, 1C). The population average for the axial ratio for sAg AD was 1.11 ± 0.08 with a range of 1.01 to 1.33 while the axial ratio average for sAg AY was 1.07 ± 0.05 with a range of 1.01 to 1.27, again suggesting representative particles were approximately spherical.

Figure 2.

Analysis of sAg morphology from subtypes AD and AY by electron microscopy. (A) Histogram displaying the frequency of diameters of quasi-spherical sAg particles within particular ranges, from human subtype AD, or (B) subtype AY. Histogram bins are at 10 nm intervals.

Probing for the presence and contribution of disulfide bonds in particles

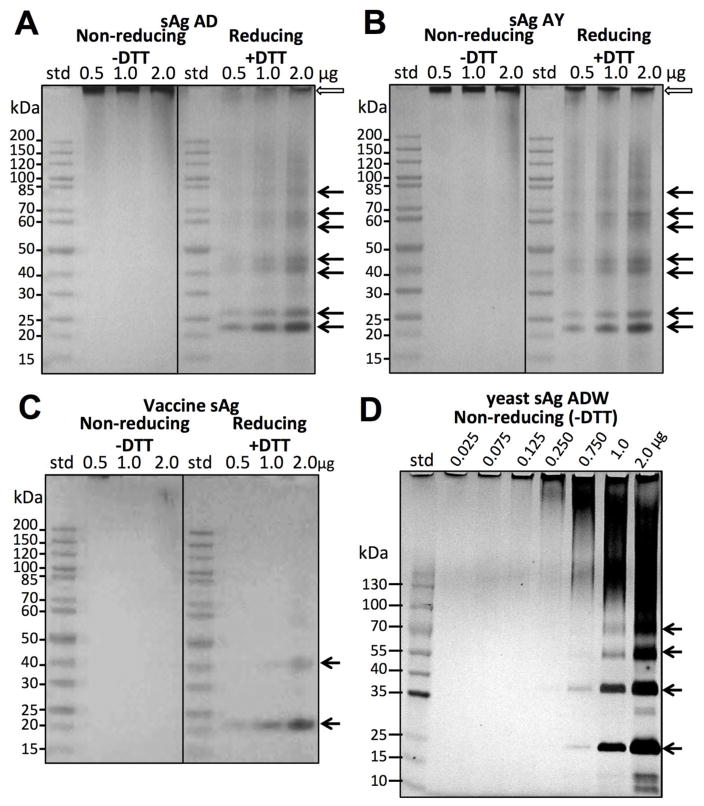

In order to address the questions of whether disulfide bonds contribute to the stability of the particles and what role they play in particle integrity, we subjected particles to SDS-PAGE analysis under non-reducing and reducing conditions using the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT). Under non-reducing conditions sAg protein was only observed at the top of the gel and no sAg bands were observed corresponding to sAg monomer or small oligomers (Figures 3A, 3B, -DTT panels). In contrast, under reducing conditions multiples bands were observed (Figures 3A, 3B, +DTT panels, arrows) and doublet patterns were observed at molecular weights corresponding to monomers and small oligomers. At least four major banding regions could be detected above background under reducing conditions with three regions having doublets (arrows, Figures 3A, 3B). The appearance of double bands was consistent with sAg being partially glycosylated, giving non-glycosylated and glycosylated bands at about 25 kDa, which is consistent for a predicted monomer of sAg (Figure S1). Relative abundance of different oligomers was assessed by considering glycosylation doublets as one single peak. Densitometry analysis of monomeric sAg (25 kDa) accounted for approximately 56%, while dimer accounted for 30%, and trimer accounted for 9% of the total sAg protein. Cysteine residues are present at 14 different locations in the primary sequence of sAg, so we used a predicted topology model to suggest how cysteine residues (Figure S1, yellow) may pair to form disulfide bonds. Topology prediction indicated four transmembrane helices along with an ectodomain (extracellular) and an endodomain region (cytoplasm/virion). The ectodomain region was predicted to contain 8 cysteines, while the transmembrane region had 2 cysteines, and the cytoplasmic domain had 4 cysteines (Figure S1).

Figure 3.

Disulfide-linked state of sAg particles by SDS-PAGE. (A) sAg AD particles and (B) sAg AY particles were under non-reducing (−DTT)(dithiothreitol) and reducing (+DTT) conditions during SDS-PAGE. Increasing amounts of sample were loaded (0.5, 1.0, 2.0 μg) with protein standards (std). Arrows indicate a ladder of at least six protein bands that are organized as three sets of doublets and a weaker seventh band on top. White block arrows denote the top of the gels where the bottoms of the loading wells are located. (C) SDS-PAGE analysis of a Recombivax HB vaccine made of recombinant surface antigen protein formulated with amorphous aluminum hydroxyphosphate sulfate as adjuvant. Samples were run under non-reducing (−DTT) and reducing (+DTT) conditions. (D) Non-vaccine yeast-derived sAg particles analyzed by SDS-PAGE in non-reducing conditions (−DTT).

Characterization of sAg particles derived from recombinant yeast systems

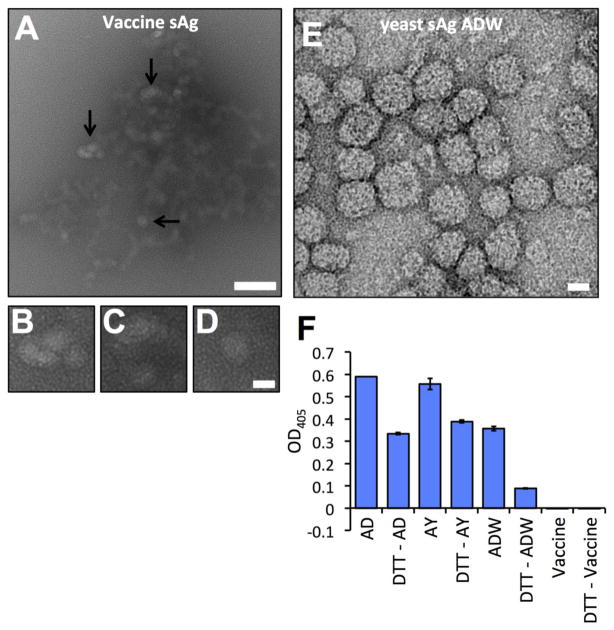

To understand how recombinant sAg particles from yeast might differ from sAg particles isolated from humans, we studied particle stability by SDS-PAGE, centrifugation assays, and electron microscopy of two types of yeast-derived recombinant sAg preparations: (i) yeast-purified subtype ADW and (ii) a commercial HBV vaccine consisting of yeast-derived sAg formulated with an aluminum hydroxide adjuvant. The results indicated variation in the level of disulfide formation between vaccine-formulated and purified yeast sAg preparations. The vaccine sAg required disulfide bond reduction via DTT in order for the sAg protein to migrate into the gel (Figure 3C). At least two single bands were detected under reducing conditions corresponding to monomer (20 kDa, 60%), and dimer (40 kDa, 40%), based on densitometry of the two major dominant bands (Figure 3C, arrows). The vaccine sAg was in the form of particles when observed by electron microscopy (Figure 4A–4D). However, the particles appeared to be in close association with adjuvant aggregates (Figure 4A). Individual sAg particles in the vaccine were resolved by negative staining mostly on the edges of aggregates (Figures 4B–4D). The surfaces of these particles were rough, with the appearance of spike protrusions, consistent with morphology observed in human sera derived samples. Although few individual vaccine sAg particles were identified due to aggregation, the average diameter of those particles was approximately 27 nm.

Figure 4.

Biochemical characterization of surface antigen vaccine preparations. (A) Image of vaccine preparation by negative-stain electron microscopy. Arrows denote particles within a larger aggregate. Scale bar, 100 nm. (B, C, D) Panels showing expanded views of particles from panel A. (E) Image of non-vaccine yeast-derived sAg particles observed by electron microscopy. Scale bars, 20 nm. (F) ELISA reactivity with goat polyclonal antibodies with human derived sAg subtypes AD and AY, compared to reactivity with sAg either as vaccine-formulated, or yeast-produced subtype ADW. For reducing conditions, samples were treated with 50 mm DTT, while non-reducing conditions were not treated with DTT. Measurements represent averages of triplicates, and error bars represent the standard deviation about the mean. All antigens were adhered to the ELISA plate at 2 μg/ml. Decreased reactivity under reducing conditions suggested some sAg epitopes were dependent upon disulfide bonding formation.

Pure, recombinant yeast particles of subtype ADW (non-vaccine) also displayed particles with rough surfaces suggestive of protein based spikes (Figure 4E). The diameters for yeast-derived sAg ADW particles ranged from 22.7 nm to 55.3 nm with an average diameter of 37.5 ± 5.3 nm. The population average axial ratio for yeast sAg was 1.15 ± 0.19 with a range of 1.0 to 2.0. Contrary to human sAg particles, disulfide bond reduction was not required for resolving yeast sAg monomers under non-reducing conditions (Figure 3D). Without DTT reduction, sAg was present as a mixture of oligomeric states, and at least four bands were distinguished at about 25 kDa, 35 kDa, 55 kDa, and 70 kDa (Figure 3D, arrows), Higher molecular weight species were not resolved into bands. Doublets were not observed for yeast sAg protein bands, suggesting that glycosylation was diminished (Figures 3A and 3B vs. Figures 3C and 3D).

Ultracentrifugation sedimentation assays were used to assess particle stability in the presence of reducing agent (DTT), and detergent (triton X-100). Yeast sAg ADW incubated with triton X-100 and subjected to sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation were found to migrate to the bottom of the gradient. Addition of both reducing agent and detergent to sAg particles caused a shift to the top of the gradient (Figure S2A, S2B), consistent with particle disassembly. Electron microscopy of the top gradient fraction revealed that the majority of sAg protein present in this fraction did not form particles (Figure S2C vs. S2D). Electron microscopy of sAg incubated in the presence of DTT alone indicated that particles were not disassembled when no detergent was added (Figure S3B). A similar result was found with triton X-100, in which the detergent alone appeared not to completely disrupt particles, although the morphology of the particles became irregular (Figure S4). Thus, we found that sAg particles produced in yeast required reducing agent and detergent to mediate complete disassembly of particles, in spite of liberation of some monomers of sAg by DTT alone, and particle morphological defects by triton-X100 alone (Figures, 4E 3D, S2, S3, S4).

Morphology of sAg vaccine preparations and sAg antigenicity

To compare sAg preparations to a known sAg immunogen, we selected the commercial HBV vaccine Recombivax, which is formulated from sAg and amorphous aluminum hydroxyphosphate sulfate as an adjuvant. To observe which native sAg epitopes were displayed in various sAg preparations, we selected a goat polyclonal antibody raised against sAg particles of type AD and AY. Polyclonal antibodies did not react with denatured sAg particles by Western blot, indicating that native particles had non linear epitopes (Figure S5). Polyclonal antibodies did react with sAg by ELISA, and we compared reactivity of sAg preparations with or without reduction of disulfide bonds. Particles of subtype AD and AY both reacted strongly with polyclonal antibody. Reactivity was decreased when sAg particles were reduced with DTT prior to binding (Figure 4F), suggesting that disruption of disulfide bonds also disrupted native structure of sAg. Yeast recombinant sAg ADW reacted approximately 65 % as strongly as human derived particles, but DTT treatment of yeast sAg ADW disrupted almost all reactivity with polyclonal antibody. Surprisingly, adjuvant formulated sAg particles reacted poorly with polyclonal antibody directed at conformational epitopes, either in the presence or absence of DTT (Figure 4F). This raises the possibility that sAg in the vaccine formulation may not display native epitopes on the particle surface that were targeted by the polyclonal antibody.

Disassembly of sAg particles

The contribution of hydrophobic interactions to particle stability was assessed by the addition of non-ionic detergent (triton X-100). Ultracentrifugation sedimentation assays were used to assess if HBV sAg particles remained whole, or disassembled into components in conditions including combinations of triton X-100 and DTT. In the presence of DTT alone, sAg particles were pelleted by ultracentrifugation and did not disassemble. However, when particles were incubated with both DTT and triton X-100, a portion of the sAg was disassembled, as judged by sAg protein remaining in the supernatant after ultracentrifugation (Figure S6, S7). In order to obtain an improved separation of disassembled sAg particles, we subjected disassembly reactions to a 5–30% sucrose gradient centrifugation. Untreated (control) sAg particles migrated to the bottom half of the gradient (Figure S8A), and sAg particles incubated with triton X-100 had a similar migration pattern (Figure S8B). Incubation of sAg particles with both DTT and triton X-100 caused a shift of sAg to the top of the gradient (Figure S8C). Thus, as observed by SDS-PAGE, centrifugation pelleting, and gradient centrifugation analyses, reduction of disulfides bonds were required for detergent-mediated disassembly of human sAg particles (Figures 3, S6, S7, S8).

To address if ionic interactions play an important role in sAg particle stability, we assayed sAg particles for stability increasing salt concentrations. Particles of human sAg AD were incubated in NaCl concentrations of 1 M, 1.5 M, 2 M, or 2.5 M in the presence of DTT. Particle formation was observed by negative stain EM, and we found that particles retained native-like morphology in all cases (Figure S9A–D). We further asked if urea, a denaturant of soluble protein, would disassemble sAg particles. We incubated particles with urea at concentrations of 2 M, 4 M, or 6M in the presence of DTT. Again we observed that native-like morphology was retained by negative stain EM (Figure S9E–G). These findings suggest that sAg particle morphology is maintained by hydrophobic interactions in the putative transmembrane region (Figure S1).

Reassembly of surface antigen particles

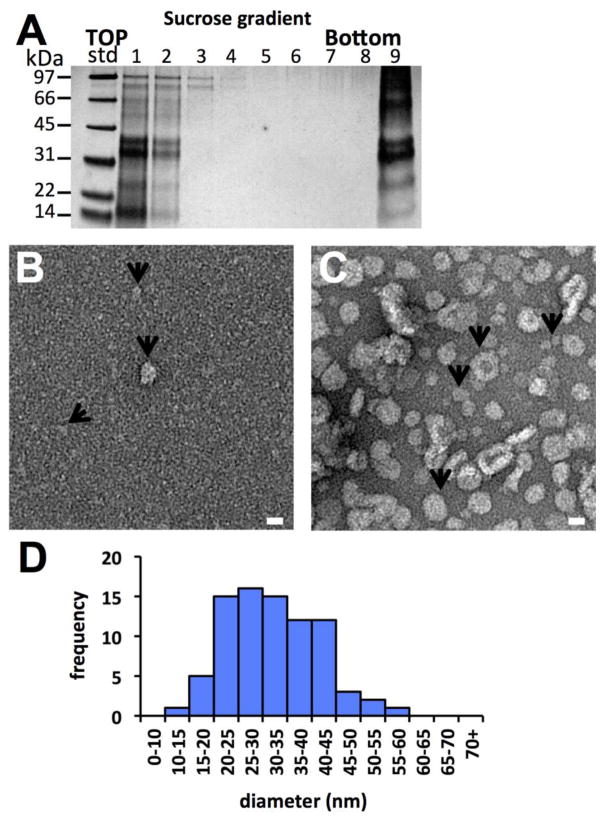

Having established that sAg particles could be disassembled via reduction and detergent treatment, we next addressed the question of whether sAg within disassembled fractions could be reassembled via detergent removal. Human sAg subtype AD was selected for further study because of availability, but we note that morphology of AD and AY particles was indistinguishable (Figures 1 and 2), thus we would anticipate equivalent results had we selected subtype AY. The disassembly reaction was repeated, again using DTT as a reducing agent, but detergents assayed were either strictly non-ionic, or a mixture of non-ionic and ionic, to assay for morphological effects on reassembly. The non-ionic detergent triton X-100 was able to extract sAg protein from particles (Figure 5A), as seen before in disassembly reactions and confirmed by electron microscopy (Figure 5B, arrows). Reassembly of particles was initiated by removal of detergent via incubation of complexes from the top of sucrose gradient with Bio-Beads SM-2, which are detergent-absorbing beads. Following detergent removal, we found by electron microscopy that particles had spontaneously reassembled (Figure 5C). The reassembled particles had diameters that ranged from 15.2 nm to 61.7 nm with an average diameter of 33.2 ± 9.1 nm (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Characterization of sAg particle disassembly and reassembly by addition and removal of non-ionic detergent. (A) SDS-PAGE of sAg disassembly reaction containing human sAg AD, DTT and triton X-100 by subsequent sucrose gradient centrifugation. Fractions are numbered starting from the top of the gradient. (B) Electron micrograph of fraction 1 from the gradient. Arrows denote complexes smaller than particles but with one larger particle in the center of the image. (C) Electron micrograph of the sAg top fraction preparation after detergent removal via SM2 bio-beads. Arrows denote complexes with varying sizes. Scale bars 20 nm. (D) Histogram displaying the frequency of ranges of diameters of the reassembled particles.

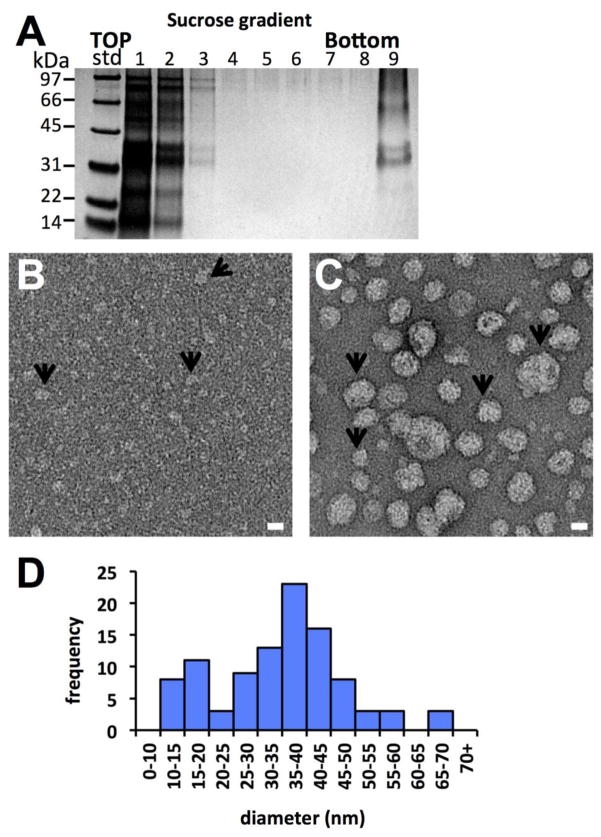

In order to test the affect of an ionic detergent mixture on disassembly and reassembly, sAg was incubated with both triton X-100 and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) detergents under reducing conditions. Results were similar to the triton X-100 analysis except that disassembly of sAg particles appeared more efficient (Figure 6A). Also, while occasional mini-particles were observed with triton X-100 disassembly, SDS mediated disassembly of particles was complete and only small oligomers were observed (Figure 6B, arrows). These complexes likely represented the same oligomers that were resistant to DTT and triton X-100 by SDS-PAGE (Figure S6B). After detergent removal, the sAg protein formed particles (Figure 6C, arrows). Diameters of the reassembled particles ranged from 11.7 nm to 67.7 nm with an average diameter of 34.7 ± 12.5 nm (Figure 6D). The average diameters from the two reassembled particle assays (33.2 and 34.7 nm, Figures 5 and 6) were larger than the starting sAg particles (27.9 nm) (Figure 1), which was statistically significant (P < 5E-5, Figure S10).

Figure 6.

Characterization of sAg particle disassembly and reassembly by addition and removal of non-ionic and ionic detergents. (A) SDS-PAGE of sAg disassembly reaction containing human sAg AD, DTT, triton X-100 and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) by subsequent sucrose gradient centrifugation. Fractions are numbered starting from the top of the gradient. (B) Electron micrograph of fraction 1 from the gradient. Arrows denote some complexes apparently smaller than input particles. (C) Electron micrograph of the sAg top fraction preparation after detergent removal via SM2 bio-beads. Arrows denote some complexes with varying sizes. Scale bars 20 nm. (D). Histogram displaying the frequency of ranges of diameters of the reassembled particles.

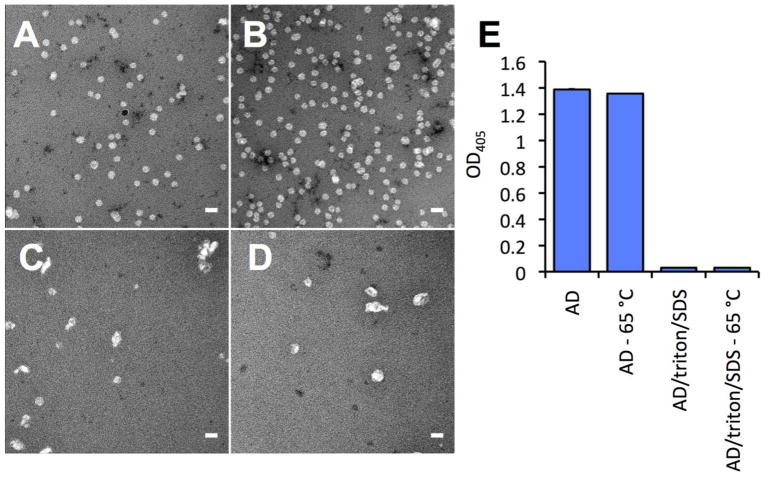

Native sAg particles were stabile at increased temperatures such as 65 °C. To test if reassembled sAg particles retained stability at 65 °C, we incubated native and reassembled sAg AD at 65 °C for 10 min before preparing samples for negative staining and EM imaging. For native (human derived) sAg, no differences in morphology were observed after the incubation period (Figure 7A, 7B). Reassembled sAg particles also showed similarities before and after the incubation period, except the prevalence of particles was marginally reduced after incubation at 65 °C, particularly for the particles that were larger than in the native sAg preparation (Figure 7C, 7D). Also apparent in the assay was the decrease in particle count after particle reassembly. Samples were prepared by holding sAg concentration constant between native and reassembled sAg particles, thus the reduced particle count likely reflects the efficiency of the reassembly process.

Figure 7.

Heat stability and antigenicity of reassembled sAg particles. (A) Native sAg AD particles incubated at 25 °C for 10 min before negative staining. (B) Native sAg AD particles incubated for 65 °C for 10 min prior to negative staining. (C) Reassembled sAg AD particles incubated at 25 °C for 10 min before negative staining. (D) Reassembled sAg AD particles incubated for 65 °C for 10 min prior to negative staining. Scale bars, 50 nm. (E) ELISA reactivity of a polyclonal antibody raised to native sAg particles with native particles (AD, AD-65C) and with reassembled particles (AD/triton/SDS samples).

Antigenicity of sAg particles before and after reassembly was probed using polyclonal antibody raised to native sAg particles. Native sAg particles reacted strongly with polyclonal antibody, while we observed no significant reactivity with reassembled particles (Figure 7E). This was surprising as at least a subset of sAg particles observed in reassembled preparations were appropriately sized, suggesting that the outer surface of these particles was somehow distinct from the surface of native particles.

To understand if modulating the salt concentration during particle reassembly would improve yield or modulate particle morphology, we performed a reassembly reaction in varying concentrations of NaCl, compared to PBS, which was used previously (137 mM NaCl). 20 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.2 with either 100 mM or 500 mM NaCl was used for reassembly, and samples were negatively stained for imaging by electron microscopy. While the difference between 100 mM and 500 mM NaCl is often substantial enough to affect protein folding of salt-sensitive proteins, we observed no differences in reassembled sAg particles (Figure S9H, S9I). Particle morphology and apparent yield were consistent between these two conditions, suggesting the salt concentration did not have a strong effect on particle reassembly.

DISCUSSION

Control of particle assembly and stability is important for nanoparticle based vaccine design. In order to address questions about the types of molecular interactions that mediate oligomerization of HBV sAg in nanoparticles, we studied sAg particles from different sources by electron microscopy. We used size measurements and biochemical analysis in order to probe the nature of the forces that drive in vitro disassembly and reassembly.

sAg nanoparticle size variation and subunit cross-linking

The particle diameters for sAg particles that we report here are larger and show a wider range than the 22 nm reported previously for recombinant sAg isolated from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (29), possibly due to a more inclusive method of sample preparation. We observed many particles with a diameter of 22 nm, but we also observed a wider distribution of particle sizes mostly bigger than 22 nm (Figures 2, S10). Hepatitis B virus particles contain a viral capsid surrounded by a layer of sAg glycoprotein (Figure 1A). These virions, originally called Dane particles, were described after the discovery of sAg, and are about 42 nm in diameter (12–14). Thus, this sAg layer on the virus (42 nm) is larger than the diameters of the different human surface antigen particle preparations reported in this work (25 to 37 nm). This implies that the sAg-sAg interactions are flexible enough to allow changes in the relative curvature of the sAg layer, in order to assemble into different sizes. This plasticity may be important in that it would allow sAg to encapsidate its viral capsid during hepatitis B virus assembly (15, 16, 30).

Our results indicated that the relative size of the sAg nanoparticles were anti-correlated with the level of disulfide cross-linking. Human-derived and vaccine sAg particles had average diameters less than 30 nm (25 nm and 27 nm, respectively, Figures 1B, 1C, 4A) and were cross-linked by disulfide bonds (Figure 3A, 3B, 3C). In contrast, recombinant, non-vaccine formulated yeast sAg and reassembled sAg particles had average diameters greater than 30 nm (Figures 4E, 5D, 6D). The extent of yeast sAg disulfide bonding was less than human and vaccine sAg in that under non-reducing conditions, sAg monomers and oligomers could be observed by SDS-PAGE (Figure 3D), while human and vaccine sAg required reducing conditions to observe sAg monomers and oligomers (Figure 3A, 3B, 3C). Our results are consistent with reports that sAg vaccine preparations are exposed to an oxidizing environment in order to promote disulfide bond formation, which is needed for epitope maturation (31, 32).

Our biochemical and electron microscopy analyses of sAg particles indicated that particles were robust to reducing agent treatment in the absence of detergent, but the combination of detergent and reducing readily disassembled sAg particles (Figures 3A, 3B, 3C). We confirmed particle stability and disassembly using electron microscopy, noting that detergent alone caused irregular morphology of sAg particles even though particles persisted (Figure S4). These results suggested that disulfide bonds alone are not responsible for sAg particle integrity, but that hydrophobic forces play an important role. The sAg has four predicted transmembrane regions (Figure S1) with cysteines in the extracellular, transmembrane, and cytoplasmic regions (Figure S1). Cysteine residues in the hydrophilic loops have been shown to participate in intermolecular disulfide bonding (33). Our observations suggest that there are specific macromolecular interactions responsible for sAg particle architecture, and these interactions could give insights into the design of vaccine nanoparticles based upon different viruses or display platforms.

Vaccine nanoparticle formation

Based on our analysis of sAg particles and comparison with other reported viral proteins, disulfide bond formation is likely to affect structure and epitope display of viral nanoparticles. For example, recombinant nanoparticle vaccines based on human papillomavirus capsids and influenza hemagglutinin glycoproteins require correct disulfide bond formation for assembly and vaccine efficacy (5, 34–37). Furthermore, highly immunogenic virus-like particles formed from recombinant papillomavirus L1 major capsid protein are the basis for the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine (5, 8). These capsid particles of L1 require intermolecular disulfide bond formation for maturation. Similarly, the Simian Virus 40 major capsid protein VP1 requires disulfide bonding (34, 38, 39).

Specific to sAg, we found reactivity of sAg particles with polyclonal antibodies raised to native particles was diminished under reducing conditions (Figure 4F). Furthermore, vaccine formulation of sAg particles almost entirely abrogated reactivity with the same polyclonal antibody (Fig 4F). This would suggest that the epitopes targeted in the goat polyclonal to native sAg particles are not the same epitopes that lend the vaccine its efficacy.

Coupling of assembly and disulfide bond formation may be dependent on the particular sequence and structure of the constituent viral protein as well as the size and molecular arrangement of the particles. Some sAg cysteines cannot be mutated and are essential for secretion of sAg particles and antigenicity (32, 33), while other cysteines can be mutated to alanine without affecting particle formation. Still, those constructs containing cysteine to alanine mutations were found to be less immunogenic (40). Our analysis of sAg particles indicated that the level of disulfide bond formation varied depending on the expression system, and was heterogeneous among sAg particles. This suggests that some disulfide bond formation between sAg subunits occurs after particle assembly. In contrast, computationally designed nanoparticles have been used to design vaccines by removing native disulfide bonds, which resulted in increased nanoparticle stability. This was observed for influenza hemagglutinin vaccine nanoparticles in which some regions containing cysteines that make intra- and inter-disulfide bonds have been removed (6, 37).

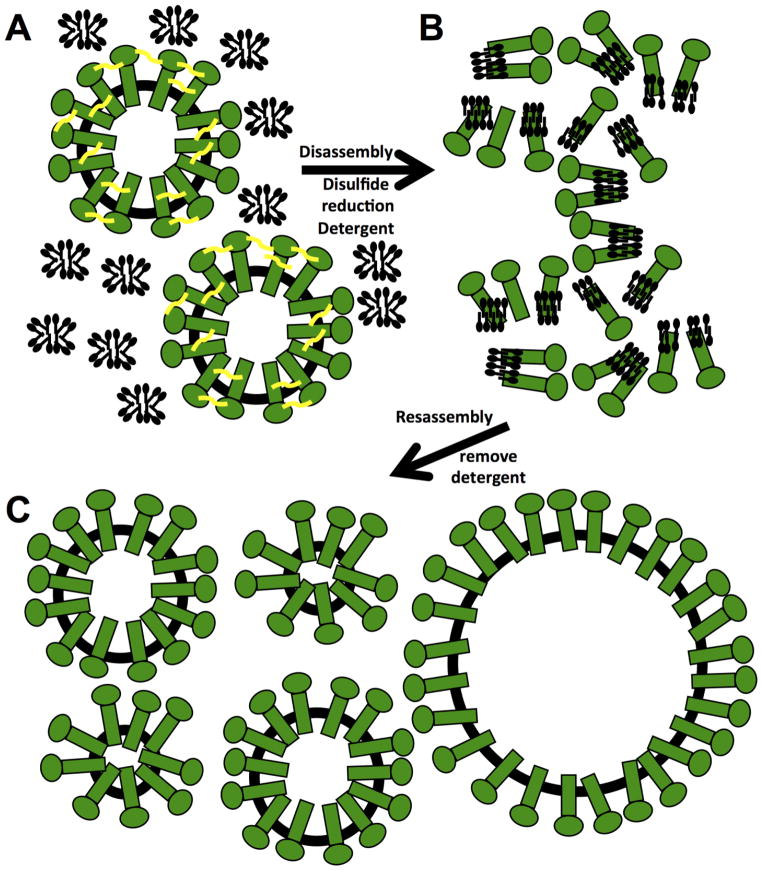

Disassembly and reassembly of viral proteins into nanoparticles

We observed that disassembly of sAg particles required both the reduction of disulfide bonds and the addition of detergent, suggesting a model where reduction of disulfide bonds allows accessibility for detergent to transmembrane regions (Figure 8). Meanwhile, particles were resistant to reducing agent when combined with salt or urea (Figure S9). Removal of detergent from detergent treated, solubilized sAg resulted in formation of sAg particles, termed here as reassembly (Figure 8). These reassembled particles have a wider range of diameters than the input particles in the disassembly reaction (Figure S10). Reassembled particles lost native epitopes as indicated by reactivity with polyclonal antibody raised to native particles (Figure 7). Nonetheless, most particles that had reassembled were not denatured at 65 °C, therefore they retained stability at increased temperature like native sAg particles. We note that vaccine formulated sAg particles also lost native epitopes detected by polyclonal antibody (Figure 4F), suggesting that epitopes displayed on the surface of native sAg particles actually may not be critical to particle stability, or even capacity to display appropriate antigen. We sought an antibody that would be effective to characterize sAg particles both in ELISA and Western format, but we were unsuccessful, and further work would benefit from a broadened search for an appropriate antigenic reporter.

Figure 8.

Schematic model for the in vitro disassembly and reassembly of surface antigen glycoprotein nanoparticles. (A) Schematic of intact particles (green) with schematics of non-bound detergent molecules as micelles (black). Disulfide bonds are represented by yellow connecting curve segments (yellow). (B) Particles are disassembled into protein-detergent complexes by reduction of disulfide bonds and incubation with detergents, which bind hydrophobic transmembrane regions of the surface antigen (sAg) proteins. (C) Reassembly of particles occurs after removal of detergent. Assembled particles have more variable sizes with smaller and larger particles suggesting a model of plasticity in that hydrophobic interactions drive reassembly and particle integrity.

The stability of sAg particles in salt or urea, considered with the complete disassembly of particles in detergent suggested that hydrophobic interactions were the basis of sAg oligomerization (Figure S9). Furthermore, modulating salt concentration during particle reassembly did not produce observable differences in the reassembled particle morphology or yield (Figure S9). Variance in particle size, particularly for reassembled particles, could be mediated by van der Waals interactions between transmembrane regions, which could allow for plasticity in sAg-sAg interactions. Plasticity would give rise to sAg particles of different sizes. Although sAg particles of 22 nm diameter have been reported to have octahedral symmetry, our results suggest that other organizations could be possible based on the larger and smaller sizes of the reassembled sAg particles.

Differences in particle size or polymorphism have been observed in other viral systems. For example the polyomavirus major capsid protein VP1 exhibits polymorphism in virus-like particle assembly in vitro resulting in different particles types: 24-capsomer octahedral, 12-capsomer icosahedral particles and 72-capsomer particles (26). Moreover, this VP1 is purified from bacteria and can form pentamers that assemble into virus-like particles, resembling native polyomavirus (25). Also, self-assembly has been shown for recombinant papillomavirus L1 major capsid protein that can form virus-like particles that are highly immunogenic and the basis of human papillomavirus vaccine (5, 8).

Viral glycoprotein of different families can also have particles of varying sizes. For symmetrical viruses with icosahedral symmetry, the arrangement of the protein can be described as a triangulation number, T (46–48). Zika virus, which is a flavivirus, can have 180 copies of the envelope protein (T=3 icosahedral symmetry, 50 nm diameter). However, even for symmetrical viruses like flaviviruses, the envelope protein can be polymorphic, as illustrated by the flavivirus, tick-borne encephalitis virus, in which the viral envelope protein can be presented as a smaller (T=1 icosahedral) virus-like particle (31.5 nm diameter) with 60 copies of the viral glycoprotein packed as dimers (49). While the use of negative stain electron microscopy in our study provided strong image contrast to assess the morphology of individual nanoparticles, unfortunately the method is not well suited for high resolution necessary to observe symmetry in the particles, such as previously reported octahedral symmetry (11, 29). We note that when we reassembled HBV sAg particles, their diameter was larger than the 22 nm octahedral particles reported previously, and we interpret the larger sAg particles as reflecting the larger sizes needed for the sAg layer to cover the capsid in the virion, which has a sAg layer about 42 nm in diameter. Even in infectious virions, the sAg layer is known to be variable (13, 14). Thus, like the size differences we observed for sAg particles, viral glycoproteins can display polymorphisms in their structural arrangement illustrated by size differences.

In conclusion, our results suggest that sAg particles from varied sources such as human sera and commercial vaccine preparations are predominantly spherical in morphology and are of similar sizes. In the absence of reducing agent, human and vaccine sAg particle preparations contained disulfide bonds that appeared to hinder detergent-mediated release of constituent sAg molecules from particles. This was in contrast to sAg particles purified from yeast that had both larger particle sizes and fewer disulfide bonds among sAg molecules within particles. The molecular basis for particle integrity was further studied by disassembling particles into smaller complexes by disulfide reduction and detergent treatment. Detergent removal resulted in reassembled sAg particles with larger variations in sizes than input particles. Thus, in vitro nanoparticle disassembly and reassembly reactions suggest once disulfide bonds in HBV sAg are reduced, hydrophobic interactions can be manipulated with detergent to control particle formation. Further analysis of disassembly and reassembly of viral glycoprotein nanoparticles such as sAg will be important for understanding and optimizing the design and assembly of epitope-displaying vaccine nanoparticles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purified surface antigen particles (sAg)

Samples of purified HBV surface antigen (sAg) particles of subtypes AD and AY from human sera were at initial concentrations of 14 mg/ml in PBS (The Binding Site Inc. San Diego, CA). HBV vaccine consisting of recombinant yeast-derived surface antigen (S domain) was from a commercial vaccine (Recombivax HB, ADW subtype, Merck & co., Inc.). Samples of affinity purified recombinant HBV sAg particles composed of the small (S) domain were kindly provided by Dr. Paul Wingfield (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The concentration of these yeast expressed HBV sAg particles was 1mg/ml. The structural integrity of the particles was confirmed by electron microscopy.

Electron microscopy of negatively stained samples

Images of samples and various centrifugation fractions were recorded on a CM120 electron microscope with LaB6 illumination operating at 120 KeV or Tecnai 12 electron microscopy at 100 KeV (FEI, Eindoven, Netherlands). For negative staining, samples were stained with 1% uranyl acetate or 3% phosphotungstic acid. Images were recorded on a 1,024 × 1,024-pixel CCD camera (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA) for CM120 at a nominal magnification of 77,000 ✠ at the CCD (0.316 nm pixels). For the Tecnai 12 electron microscope images were recorded on a 4096 × 4,096-pixel OneView camera (Gatan) at nominal magnifications of 30,000 ✠ (0.377 nm pixels) and 52,000 ✠ (0.217 nm pixels). Samples were negatively stained with uranyl acetate replacement (UAR) (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). Diameter measurements of particles were carried out in IMOD (50) by modeling major and minor elliptical axes with line-segments, and results were reported using the standard deviation to estimate error. Statistical significance between particle diameters was determined using Tukey’s HSD test (to account for multiple pairwise comparisons), as implemented in the statistical software R.

Analysis of surface antigen (sAg) particles by cryo-electron tomography

Human sAg AD (14mg/ml) was diluted with PBS to 1mg/ml and mixed with an equal volume of 10-nm colloidal gold particles stabilized with 0.002% BSA (Ted Pella Inc., Redding, CA). Gold particles were used as fiducial markers for tomogram reconstruction. The particle and gold mixture (6 μl drops) was applied to holey carbon film substrates, blotted to a thin film, and vitrified by plunging into liquid ethane before transfer into a liquid-N2-cooled specimen holder (model 626 - Gatan, Warrendale, PA). A Tecnai-12 cryo-electron microscope (FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) operating at 120 keV was used to record single-axis tilt series of projections at 1.5° steps, covering a range of −70° to +70°. The microscope was equipped with a post-column energy filter (Gatan) that was operated in the zero-energy-loss mode with a slit width of 20 keV. Images were recorded on a 2,048 × 2,048-pixel CCD camera (Gatan) at 38,000x magnification (0.78 nm pixels) or at a 53,900 x magnification (0.55 nm pixels) at 3 μm defocus, corresponding to first zeros of the contrast transfer function at (1/3.2 nm). Data were recorded under low-dose conditions, using SerialEM to conduct automatic tilting, tracking, and focusing and image acquisition (51). The cumulative electron dose was 70 electrons/Å2. Projections in the tilt series were aligned using gold particles as fiducial markers, and the volume reconstructed by weighted back-projection. The above image processing steps were carried out with the B-soft software package (52).

Analysis of samples and fractions by SDS-PAGE

Samples and centrifugation fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under non-reducing and reducing conditions and gels were silver-stained using the SilverQuest Kit according to the manufacture’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) For reducing conditions dithiothreitol (DTT) was used as the reducing agent. The relative amounts of protein were estimated for the bands. Gels were digitized with an electrophoresis documentation system (Labnet International, Inc., Edison, NJ). The program Fiji (53) was used to measure the relative purity of and migration of the bands by 1D profiles of the relative densities of the protein bands in the gels. Areas under the individual peaks were divided by the total area under the curve to estimate the percentage of protein in each band.

Polyclonal antibody binding to sAg

Polyclonal goat antibody PA1-73082, which was directly coupled to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and raised to sAg particles of subtype AD and AY (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), was used to probe sAg either by ELISA for Western analysis. ELISA plates were coated with sAg at a concentration of 2 μg/ml, before incubating with α sAg antibody, at a concentration of 1.5 μg/ml. Binding was quantified by the addition of ABTS substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and optical density was measured at a wavelength of 405 nm. Western analysis was performed using the Millipore SNAPi.d. system (EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked with 0.5 % non-fat milk, 0.1 % tween, in TBS. Blots were again probed with HRP coupled α sAg goat polyclonal antibody at a concentration of 1.5 μg/ml, and visualized using SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to expose film.

Disassembly of sAg particles

Surface antigen (sAg) oligomers were isolated via gradient centrifugation after intact particles were reduced with 50 mM of dithiothreitol (DTT), and disrupted with detergent. Detergent was either 2.5 % of triton X-100 alone, or 2.5 % of triton X-100 in addition to 1.0 % sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). The final concentration of Human-sAg AD in the disruption reaction was 1mg/ml. Surface antigen (35 μl at 14 mg/ml) was mixed with the following reagent volumes: 125 μl of triton X-100 or plus SDS (10 % stock) 25 μl DTT (1 M stock), and 315 μl of buffer (100 mM Hepes, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2 % NaN3, pH 7.5). The reaction was incubated at 25 °C for 2 hr. Intact particles and aggregated material was separated from solubilized sAg by centrifugation via velocity sedimentation (see below). Salt treatment of sAg particles was performed with 400 μg/ml sAg subtype AD in the presence of 50 mM DTT and NaCl at a concentration of 1 M, 1.5M, 2M, or 2.5 M. Samples were incubated 5 hr at 25 °C. Urea treatment of sAg particles was performed as with salt treatment, except instead of NaCl, urea was added at a concentration of 2 M, 4 M, or 6M.

Gradient separation of sAg oligomers vs. particles

Velocity sedimentation through sucrose gradients was used to further assess the presence of oligomers vs. particles in the disassembly reactions. Intact particles and aggregated material would pellet while soluble material would remain at the top of the gradient. The supernatants from the disassembly reactions were layered on top of a 5–30 % linear sucrose gradient. The samples were centrifuged in a SW 55 Ti rotor Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) at 32,500 rpm (100,000 ✠ g) for 6 hrs at 20 °C. Fractions (400 μl) were collected from the top to bottom of the gradient and the pellet was resuspended in 400 μl of PBS. Fractions were analysis by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Also, fractions were visualized by electron microscopy.

Reassembly of sAg into nanoparticles

Surface antigen oligomers were assembled into particle-like structures by detergent removal. The upper fractions of the sucrose gradient that contained disassembled sAg, as judged by migration in the gradient by SDS-PAGE, were subjected to reassembly by detergent removal by Bio-Beads SM-2. The amount of Bio-Beads SM-2 was prepared according to the manufactures instructions (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The upper sAg gradient fractions of the disassembly reactions were then added to 0.1 g of bio-beads. The reactions were incubated and rotated overnight at 4 °C. Supernatants from the reassembly reactions were visualized by electron microscopy.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Vaccines are an important means by which the morbidity and mortality associated with infectious diseases are reduced. Recombinant vaccine nanoparticles as applied to viral vaccines is emerging as a field where viral epitopes are displayed on designed nanoparticles. While nanoparticle vaccine technology is gaining interest due to the success of vaccines like those for the human papillomavirus that is based on viral capsid nanoparticles, little information is available on the disassembly and reassembly of viral surface glycoprotein-based nanoparticles. One such particle is the hepatitis B virus surface antigen (sAg) that exists as nanoparticles. This was the first recombinant vaccine licensed and it is a nanoparticle. The original nanoparticle vaccine was isolated from human sera. This motivated us to further study of this “classical” viral vaccine nanoparticle and discuss similarities and differences with contemporary recombinant viral vaccine nanoparticles.

Here we show, using biochemical analysis coupled with electron microscopy, that sAg nanoparticle disassembly requires both reducing agent to disrupt intermolecular disulfide bonds, and detergent to disrupt hydrophobic interactions that stabilize the nanoparticle. We reassembled isolated sAg protein into nanoparticles by detergent removal and reassembly resulted in a wider distribution of particle diameters. This suggests that the driving mechanism of sAg nanoparticle assembly involves hydrophobic interactions. Knowledge of these driving forces of nanoparticle assembly and stability should facilitate construction of nanoparticles tailored to display specific epitopes and that can be used as immunogens in vaccines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. We thank Dennis Winkler (NIAMS, NIH) for aid with electron microscopy data collection and Paul Wingfield (NIAMS, NIH) for providing the reagent of the recombinant surface antigen (sAg) from yeast.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Baker TS, Olson NH, Fuller SD. Adding the third dimension to virus life cycles: three-dimensional reconstruction of icosahedral viruses from cryo-electron micrographs. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:862–922. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.4.862-922.1999. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grunewald K, Cyrklaff M. Structure of complex viruses and virus-infected cells by electron cryo tomography. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:437–442. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subramaniam S, Bartesaghi A, Liu J, Bennett AE, Sougrat R. Electron tomography of viruses. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopez-Sagaseta J, Malito E, Rappuoli R, Bottomley MJ. Self-assembling protein nanoparticles in the design of vaccines. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2016;14:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiller JT, Lowy DR. Raising expectations for subunit vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:1373–1375. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yassine HM, Boyington JC, McTamney PM, Wei CJ, Kanekiyo M, Kong WP, Gallagher JR, Wang L, Zhang Y, Joyce MG, Lingwood D, Moin SM, Andersen H, Okuno Y, Rao SS, Harris AK, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, Graham BS. Hemagglutinin-stem nanoparticles generate heterosubtypic influenza protection. Nat Med. 2015;21:1065–1070. doi: 10.1038/nm.3927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beardsley T. Genetic engineering. Hepatitis vaccine wins approval. Nature. 1986;322:396. doi: 10.1038/322396a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirnbauer R, Booy F, Cheng N, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Papillomavirus L1 major capsid protein self-assembles into virus-like particles that are highly immunogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:12180–12184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Printz C. FDA approves Gardasil 9 for more types of HPV. Cancer. 2015;121:1156–1157. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayer ME, Blumberg BS, Werner B. Particles associated with Australia antigen in the sera of patients with leukaemia, Down’s Syndrome and hepatitis. Nature. 1968;218:1057–1059. doi: 10.1038/2181057a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert RJ, Beales L, Blond D, Simon MN, Lin BY, Chisari FV, Stuart DI, Rowlands DJ. Hepatitis B small surface antigen particles are octahedral. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14783–14788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505062102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dane DS, Cameron CH, Briggs M. Virus-like particles in serum of patients with Australia-antigen-associated hepatitis. Lancet. 1970;1:695–698. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)90926-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dryden KA, Wieland SF, Whitten-Bauer C, Gerin JL, Chisari FV, Yeager M. Native hepatitis B virions and capsids visualized by electron cryomicroscopy. Mol Cell. 2006;22:843–850. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seitz S, Urban S, Antoni C, Bottcher B. Cryo-electron microscopy of hepatitis B virions reveals variability in envelope capsid interactions. EMBO J. 2007;26:4160–4167. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruss V. Envelopment of the hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid. Virus Res. 2004;106:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruss V. Processing of hepatitis B virus surface proteins. Methods Mol Med. 2004;95:189–198. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-669-X:189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valenzuela P, Medina A, Rutter WJ, Ammerer G, Hall BD. Synthesis and assembly of hepatitis B virus surface antigen particles in yeast. Nature. 1982;298:347–350. doi: 10.1038/298347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Einarsson M, Kaplan L, Utter G. Purification of hepatitis B surface antigen by affinity chromatography. Vox Sang. 1978;35:224–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1978.tb02926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zuckerman AJ. Safety of hepatitis-B vaccines containing intact 20 nm particles. Lancet. 1979;1:547–548. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90961-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoofnagle JH, Gerety RJ, Smallwood LA, Barker LF. Subtyping of hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody by radioimmunoassay. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:290–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown SE, Stanley C, Howard CR, Zuckerman AJ, Steward MW. Antibody responses to recombinant and plasma derived hepatitis B vaccines. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292:159–161. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6514.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiller JT, Lowy DR. Understanding and learning from the success of prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:681–692. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanekiyo M, Bu W, Joyce MG, Meng G, Whittle JR, Baxa U, Yamamoto T, Narpala S, Todd JP, Rao SS, McDermott AB, Koup RA, Rossmann MG, Mascola JR, Graham BS, Cohen JI, Nabel GJ. Rational Design of an Epstein-Barr Virus Vaccine Targeting the Receptor-Binding Site. Cell. 2015;162:1090–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He L, de Val N, Morris CD, Vora N, Thinnes TC, Kong L, Azadnia P, Sok D, Zhou B, Burton DR, Wilson IA, Nemazee D, Ward AB, Zhu J. Presenting native-like trimeric HIV-1 antigens with self-assembling nanoparticles. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12041. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salunke DM, Caspar DL, Garcea RL. Self-assembly of purified polyomavirus capsid protein VP1. Cell. 1986;46:895–904. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salunke DM, Caspar DL, Garcea RL. Polymorphism in the assembly of polyomavirus capsid protein VP1. Biophys J. 1989;56:887–900. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82735-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steven AC, Conway JF, Cheng N, Watts NR, Belnap DM, Harris A, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT. Structure, assembly, and antigenicity of hepatitis B virus capsid proteins. Adv Virus Res. 2005;64:125–164. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(05)64005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akahata W, Yang ZY, Andersen H, Sun S, Holdaway HA, Kong WP, Lewis MG, Higgs S, Rossmann MG, Rao S, Nabel GJ. A virus-like particle vaccine for epidemic Chikungunya virus protects nonhuman primates against infection. Nat Med. 2010;16:334–338. doi: 10.1038/nm.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulder AM, Carragher B, Towne V, Meng Y, Wang Y, Dieter L, Potter CS, Washabaugh MW, Sitrin RD, Zhao Q. Toolbox for non-intrusive structural and functional analysis of recombinant VLP based vaccines: a case study with hepatitis B vaccine. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Pogam S, Yuan TT, Sahu GK, Chatterjee S, Shih C. Low-level secretion of human hepatitis B virus virions caused by two independent, naturally occurring mutations (P5T and L60V) in the capsid protein. J Virol. 2000;74:9099–9105. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.19.9099-9105.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Q, Towne V, Brown M, Wang Y, Abraham D, Oswald CB, Gimenez JA, Washabaugh MW, Kennedy R, Sitrin RD. In-depth process understanding of RECOMBIVAX HB(R) maturation and potential epitope improvements with redox treatment: multifaceted biochemical and immunochemical characterization. Vaccine. 2011;29:7936–7941. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mangold CM, Unckell F, Werr M, Streeck RE. Secretion and antigenicity of hepatitis B virus small envelope proteins lacking cysteines in the major antigenic region. Virology. 1995;211:535–543. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mangold CM, Unckell F, Werr M, Streeck RE. Analysis of intermolecular disulfide bonds and free sulfhydryl groups in hepatitis B surface antigen particles. Arch Virol. 1997;142:2257–2267. doi: 10.1007/s007050050240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cardone G, Moyer AL, Cheng N, Thompson CD, Dvoretzky I, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, Steven AC, Buck CB, Trus BL. Maturation of the human papillomavirus 16 capsid. MBio. 2014;5:e01104–01114. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01104-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCraw DM, Gallagher JR, Harris AK. Characterization of Influenza Vaccine Hemagglutinin Complexes by Cryo-Electron Microscopy and Image Analyses Reveals Structural Polymorphisms. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2016;23:483–495. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00085-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhodes DG, Holtz K, Robinson P, Wang K, McPherson CE, Cox MM, Srivastava IK. Improved stability of recombinant hemagglutinin using a formulation containing sodium thioglycolate. Vaccine. 2015;33:6011–6016. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Segal MS, Bye JM, Sambrook JF, Gething MJ. Disulfide bond formation during the folding of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:227–244. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li F, Chen H, Ma L, Zhou K, Zhang ZP, Meng C, Zhang XE, Wang Q. Insights into stabilization of a viral protein cage in templating complex nanoarchitectures: roles of disulfide bonds. Small. 2014;10:536–543. doi: 10.1002/smll.201300860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liddington RC, Yan Y, Moulai J, Sahli R, Benjamin TL, Harrison SC. Structure of simian virus 40 at 3.8-A resolution. Nature. 1991;354:278–284. doi: 10.1038/354278a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheong WS, Hyakumura M, Yuen L, Warner N, Locarnini S, Netter HJ. Modulation of the immunogenicity of virus-like particles composed of mutant hepatitis B virus envelope subunits. Antiviral Res. 2012;93:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mach H, Volkin DB, Troutman RD, Wang B, Luo Z, Jansen KU, Shi L. Disassembly and reassembly of yeast-derived recombinant human papillomavirus virus-like particles (HPV VLPs) J Pharm Sci. 2006;95:2195–2206. doi: 10.1002/jps.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCarthy MP, White WI, Palmer-Hill F, Koenig S, Suzich JA. Quantitative disassembly and reassembly of human papillomavirus type 11 viruslike particles in vitro. J Virol. 1998;72:32–41. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.32-41.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paintsil J, Muller M, Picken M, Gissmann L, Zhou J. Calcium is required in reassembly of bovine papillomavirus in vitro. J Gen Virol. 1998;79(Pt 5):1133–1141. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-5-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao Q, Allen MJ, Wang Y, Wang B, Wang N, Shi L, Sitrin RD. Disassembly and reassembly improves morphology and thermal stability of human papillomavirus type 16 virus-like particles. Nanomedicine. 2012;8:1182–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zuckerman AJ, Howard CR. Toward hepatitis B vaccines. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1975;51:491–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caspar DL, Klug A. Physical principles in the construction of regular viruses. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1962;27:1–24. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1962.027.001.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunker AK. Structure of isometric viruses containing nonidentical polypeptide chains. J Virol. 1974;14:878–885. doi: 10.1128/jvi.14.4.878-885.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rossmann MG. Constraints on the assembly of spherical virus particles. Virology. 1984;134:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferlenghi I, Clarke M, Ruttan T, Allison SL, Schalich J, Heinz FX, Harrison SC, Rey FA, Fuller SD. Molecular organization of a recombinant subviral particle from tick-borne encephalitis virus. Mol Cell. 2001;7:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mastronarde DN. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J Struct Biol. 2005;152:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heymann JB, Cardone G, Winkler DC, Steven AC. Computational resources for cryo-electron tomography in Bsoft. J Struct Biol. 2008;161:232–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.