Abstract

Binge eating disorder and alcohol use disorder (AUD) frequently co-occur in the presence of other psychiatric conditions. Data suggest that binge eating engages similar behavioral and neurochemical processes common to AUD, which might contribute to the etiology or maintenance of alcoholism. However, it is unclear how binge feeding behavior and alcohol intake interact to promote initiation or maintenance of AUD. We investigated the impact of binge-like feeding on alcohol intake and anxiety-like behavior in male Long Evans rats. Rats received chow (controls) or extended intermittent access (24 hr twice a week; Int-HFD) to a nutritionally complete high-fat diet for six weeks. Standard rodent chow was available ad-libitum to all groups and food intake was measured. Following HFD exposure, 20.0% ethanol, 2.0% sucrose intake and endocrine peptide levels were evaluated. Anxiety-like behavior was measured using a light-dark (LD) box apparatus. Rats in the Int-HFD group displayed a binge-like pattern of feeding (alternations between caloric overconsumption and voluntary caloric restriction). Surprisingly, alcohol intake was significantly attenuated in the Int-HFD group whereas sugar consumption was unaffected. Plasma acyl-ghrelin levels were significantly elevated in the Int-HFD group, whereas glucagon-like peptide-1 levels did not change. Moreover, rats in the Int-HFD group spent more time in the light side of the LD box compared to controls, indicating that binge-like feeding induced anxiolytic effects. Collectively, these data suggest that intermittent access to HFD attenuates alcohol intake through reducing anxiety-like behavior, a process potentially controlled by elevated plasma ghrelin levels.

Keywords: Alcohol Intake, Palatable Food, Anxiety, High-Fat Diet, Ghrelin

1.0 INTRODUCTION

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) poses substantial fiscal, physical and mental health risks in the US (Bouchery et al., 2011; Grant et al., 2004). Importantly, AUD and disordered eating frequently co-occur in the presence of other psychiatric disorders (Bulik et al., 2004; Dunn et al., 2002). Specific to this topic is the observation that a significant proportion of the college-aged population engages in episodes of binge drinking and binge eating (Ferriter and Ray, 2011; Kelly-Weeder, 2011). Importantly, binge feeding behavior is further associated with emotional distress, obesity and metabolic risks (Gearhardt et al., 2014; Sonneville et al., 2013). Thus, these frequently co-occurring problems suggest greater psychiatric disturbance and medical risk (Catterson et al., 1997; Harrell et al., 2009; Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, 2005) for patients with AUD.

Binge eating, characterized by eating a large amount of food in a short period of time, as well as a sense of lack of control over food intake, is the most common behavioral manifestation present in a variety of eating disorders (Attia et al., 2013; Kessler et al., 2013). Data suggest that individuals who engage in binge eating behavior develop AUD, overweight/obesity, and worsening depressive symptoms over the course of time (Franko et al., 2005; Sonneville et al., 2013). Highly palatable foods, rich in sugar and fat, are the typically preferred foods consumed during binge episodes in humans and laboratory animals, and it is hypothesized that hedonic-based feeding (i.e., feeding in the absence of caloric need) regulates this phenomenon (Cottone et al., 2008; Yeomans et al., 2004). This is based on observations that like drugs of abuse, both sweet and fatty foods are capable of activating brain reward circuitry (Tomasi and Volkow, 2013; Volkow et al., 2012). In this context, feeding peptides that control appetite and energy metabolism also regulate the intake and reinforcing properties of alcohol (Vadnie et al., 2014). These feeding peptides are released during anticipation of scheduled meals, ingestion and storage of calories, calorie restriction and learned responses that facilitate approach behavior to food (Drazen et al., 2006; Kanoski et al., 2013; Vahl et al., 2010). Thus, any or all of these variables could mediate feeding-induced changes in alcohol intake. Both human and animal studies suggest a bidirectional positive relation between alcohol intake and consumption of sugar or fat (Avena et al., 2004; Carrillo et al., 2004; Herbeth et al., 1988; Mitchell et al., 1985). However, it is unclear how binge feeding behavior impacts alcohol consumption.

Based on DSM criteria, various rodent models of binge eating have emerged (Corwin and Babbs, 2012; Wolfe et al., 2009). Although, it is challenging to mimic all aspects of human binge eating episodes in rodent models, it has been suggested that modeling time-limited access to palatable food that induces repeated hyperphagic events could be helpful to study binge eating behavior (Perello et al., 2014). This is only possible if a palatable diet is provided in an intermittent fashion (Avena et al., 2009; Corwin and Babbs, 2012; Davis et al., 2007; Tong and D’Alessio, 2011). Utilizing this limited access (2hr) paradigm, we have recently shown that binge-like intake of high fat diet (HFD) induced anxiolytic effects and attenuated alcohol consumption in non-dependent rats (Sirohi et al., 2016). This finding could be explained by the length and exposure history of a calorie-rich food, which has fundamentally different behavioral outcomes (Krishna et al., 2016; Tracy et al., 2015) or changes in the feeding peptides, which control behavioral constructs such as motivation and anxiety that also contribute to excess alcohol intake (Barson and Leibowitz, 2016; Morganstern et al., 2011). Therefore, in the present study, we hypothesized that extended intermittent access to HFD would lead to increased alcohol consumption in non-dependent rodents. To do this, we investigated the impact of extended (24hr) intermittent access to HFD on alcohol intake, plasma levels of feeding peptides and anxiety-like behavior in rats.

2.0 MATERIAL and METHODS

2.1 Animals

Male Long-Evans rats (Harlan, IN)) were housed in an environmentally controlled vivarium on a reverse light cycle (lights off at 7 a.m.) with food and water available ad libitum in standard shoebox cages. All work adhered to the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines at Washington State University, WA.

2.2 Diets

All rats were maintained on chow (Teklad, 3.41 kcal/g, 0.51 kcal/g from fat) throughout. Rats in the experimental group received intermittent access to HFD (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, 4.41 kcal/g, 1.71 kcal/g from fat). Dietary composition of standard rodent chow and HFD has been described previously (Davis et al., 2007).

2.3 General Procedure

Rats (n=5–6/group) matched for body weight and food intake received chow (controls) or intermittent access (24 hr, every Tuesday and Thursday, only) to HFD (Int-HFD) for six weeks (Figure 1a). Following six weeks of intermittent cycling on HFD, all rats underwent a series of tests while still maintained on the intermittent HFD schedule, as outlined in the (Figure 1b and c). Standard rodent chow was available to all groups at all times. Food intake was measured daily, unless otherwise noted. First, we evaluated alcohol intake on the following days (Mon, Wed and Fri) of HFD exposure on 6 separate occasions. In order to examine if this could be due to decrease in overall caloric need following HFD intake, 2.0% sucrose consumption was examined next in the same groups under identical conditions over two separate days. HFD, alcohol and sucrose were introduced in the rat cages at the onset of dark cycle and represents a measurement over a period of 24hr, unless noted otherwise. Next, we examined anxiety-like behavior, a behavioral evaluation that required one day. To determine if the observed attenuation of alcohol drinking was a result of altered alcohol metabolism or changes in feeding peptides, both groups of rats received a final alcohol drinking session, that occurred after all other tests. Since, we observed differences in intake specifically 4–12 hours after alcohol intake had ensued, rats were allowed to drink alcohol and 11hr later tail blood samples were collected at three time points, 15min apart, to measure blood alcohol, ghrelin, and GLP-1 levels. Body weight was recorded every fourth day, except on alcohol and sucrose drinking days when rats were weighed daily.

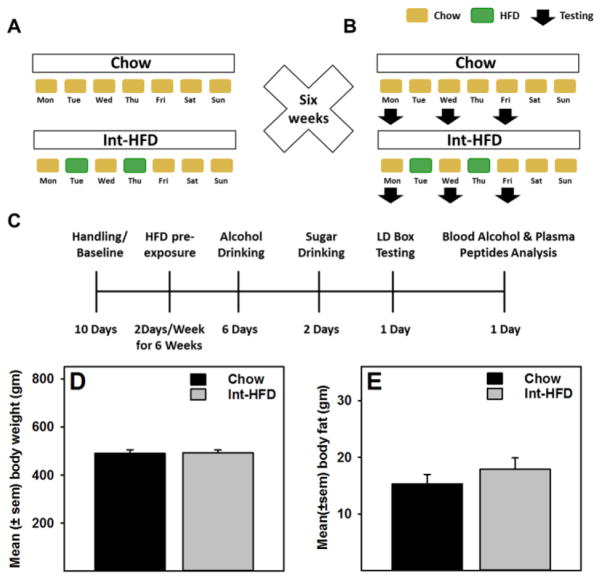

Figure 1. Schematic description of the intermittent access to a nutritionally complete high-fat diet paradigm and body weight and fat changes following experimental testing procedure.

A) Rats (n=5–6/group) matched for body weight and food intake received intermittent access (24 hr every Tuesday and Thursday) to a nutritionally complete high-fat diet (HFD) for six weeks. Following six weeks of intermittent cycling on HFD, all rats underwent a series of tests while still maintained on the intermittent HFD schedule (Figure 1b). Normal chow was available to all groups at all times. Food intake was measured daily, unless otherwise noted. C) A time line of the present study, which also depicts a series of testing that occurred following six weeks of intermittent cycling of HFD. No changes in D) body weight or E) body fat content were observed.

2.4 Alcohol and Sucrose Intake

On testing days, rats were provided with an unsweetened alcohol solution (20% v/v) using a two-bottle choice paradigm (Simms et al., 2008). The position of alcohol and water bottles were alternated between sessions to account for conditioning effects on alcohol intake. Bottles were weighed, gently placed in the cages and re-weighed manually following each session to evaluate alcohol intake (g/kg). In addition, we also evaluated alcohol consumption by manually weighing bottles at multiple time points during one separate alcohol drinking session. Therefore, data represent six separate alcohol drinking sessions, where 24hr alcohol intake was measured in the first five sessions and one separate session evaluated alcohol consumption at multiple time points. Sucrose preference was also examined under identical conditions. To do this, all rats were exposed to a 2% sucrose solution using the same two-bottle choice paradigm.

2.5 Anxiety-like Behavior

Anxiety-like behavior was measured using a light dark box apparatus, which occurred 12 days following sucrose drinking days, while rats were still on intermittent HFD cycling. Rats in each group were gently introduced in the light side (600 lux) facing dark side (4 lux) of the box and allowed to freely explore between compartments for 10 min. The total number of entries and time spent in the light side were counted by two independent investigators.

2.6 Blood Alcohol Levels & Analysis of Feeding Peptides

Blood alcohol levels were determined from tail blood samples and analyzed using Analox microstat GL5 (Analox Instruments Ltd., Lunenberg, MA). Plasma levels of acyl-ghrelin and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) were detected using a MILLIPLEX MAP Rat Metabolic Hormone Magnetic Bead Panel -Metabolism Multiplex Assay kit (RMHMAG-84K, EMD Millipore Corporation). Blood samples (0.2 ml) were collected in tubes containing EDTA, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitor and Pefabloc (an irreversible serine protease inhibitor) at concentration 1.86 mg/ml, 18.8 ug/ml and 1.0 mg/ml of blood, respectively, on ice. All samples were centrifuged at 21000g for 20 min and plasma was transferred into a separate tube on ice and stored at −20°C until further analysis. On the day of analysis, samples were thawed on ice and assayed in duplicates according to the kit manufacturer’s instructions.

2.7 Body Composition Analysis

Body composition analysis (total, lean and fat body mass) was measured using a Bruker Minispec LF110 NMR Body Composition Rat Analyzer (Bruker Biospin, Rheinstetten, Germany).

2.8 Gene Expression Analysis

Following completion of the study, rats were sacrificed and total RNA was isolated from ventral striatum using Qiagen RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, CA) and quantified using a Nano drop 2000c spectrophotometer. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was revere transcribed using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit with RNase Inhibitor (Applied Biosystems, CA). The template cDNA was mixed with Fast SYBR® Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, CA) and assayed in triplicates on a 96-well plate with appropriate negative controls to detect contamination. The mRNA expression was normalized to the expression levels of the housekeeping gene rn45s. We evaluated ghrelin receptor (GHSR) gene expression using ViiA 7 real-time PCR (qPCR) system (Life Technologies Corporation, NY). The primers (IDT, San Diego, CA, USA) used were as follows: rn45s, left-GTGGAGCGATTTGTCTG GTT and right- CGCTGAGCCAGTTCAGTGTA; GHSR, left-GCAACCTGCTCACTATGCTG and right- CAGCTCTCGCTGACAAACTG. All qPCR runs included a melt curve analysis to ensure the specificity of the primers. Relative quantification of the amount of target transcript was done using 2ΔCt method.

2.9 Statistical Analysis

Food intake, alcohol consumption, body weight during alcohol drinking session, water intake, total fluid intake, sucrose intake and feeding peptide profiles were analyzed by mixed-model two-way ANOVA, with post-hoc tests. The within-subject variable was time intervals (time of measurements) and the between-groups variable was exposure (chow or HFD). A student t-test compared body weight, body composition, light and dark box data, blood alcohol level and qPCR data. Statistical comparisons were conducted at 0.05 α level with power >0.8 (β=0.2).

3.0 RESULTS

3.1 Intermittent Access to HFD Induced a Binge/Compensate Pattern of Feeding

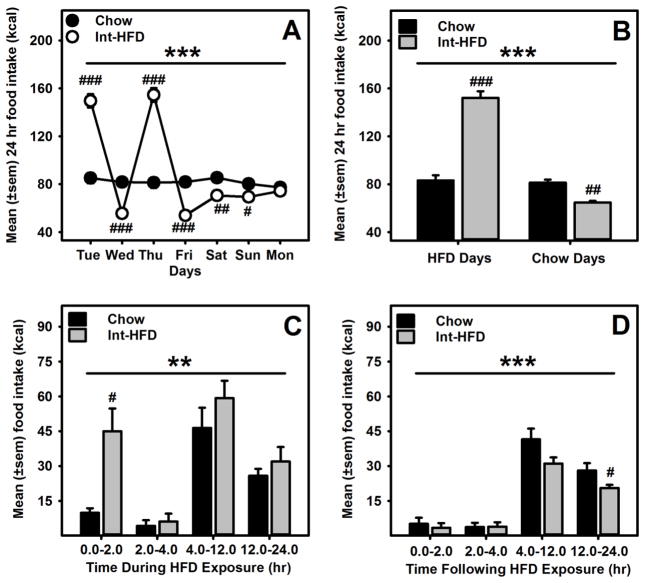

There were no differences in body weight or body fat composition between chow or Int-HFD rats following intermittent feeding protocol (Figure 1d and e). Rats receiving intermittent access to HFD displayed a pattern of caloric overconsumption followed by voluntary caloric restriction (Figure 2a). A mixed-model ANOVA identified a main effect of time (F1.566, 14.092 = 156.778, p<0.000) and a significant time and diet interaction (F1.566, 14.092 = 146.147, p<0.000) (Figure 2a). We also compared mean food intake on HFD access days to chow days and a mixed-model ANOVA further revealed a main effect of time (F1.0, 9.0 = 205.91, p<0.000), a significant time and diet interaction (F1.0, 9.0 = 188.763, p<0.000) and a significant between group effect (F1.0, 9.0 = 32.45, p<0.000), suggesting a significant increase in total caloric intake in rats on HFD access days and a compensatory under consumption from chow on the following day (Figure 2b). To further characterize our intermittent access model, we determined that hyperphagia from HFD occurred within a discrete time frame (2hr). To evaluate this, we analyzed food intake on HFD access days at various time intervals. A mixed-model ANOVA further revealed a main effect of time (F1.786, 16.07 = 15.522, p<0.000) and a significant between group effect (F1.0, 9.0 = 23.378, p<0.01) (Figure 2c). A mixed-model ANOVA further evaluated food intake following HFD access day and identified a main effect of time (F3.0, 27 = 59.964, p<0.000) and a significant between group effect (F1.0, 9.0 = 28.532, p<0.000) (Figure 2d). HFD intake was significantly higher (p<0.05) following the first two hours of HFD access and a significant (p<0.05) under consumption of chow was observed 12–24hr following HFD access (Figure 2c, d). In addition, the voluntary caloric restriction from chow persisted for two days after HFD exposure then returned to control levels (Figure 2a).

Figure 2. Effect of intermittent access to a nutritionally complete high-fat diet on daily energy consumption in male Long-Evans rats.

A) Mean (±sem) weekly food intake (kcal) from chow and HFD, respectively are presented. Rats receiving intermittent HFD access, displayed significant caloric overconsumption of HFD and voluntary caloric restriction of chow following HFD exposure days, respectively. ***p<0.000 a significant interaction effect, ###p<0.0000, ##p<0.01 and #<p<0.05 compared to chow controls on respective days. B) Overall, rats in HFD group significantly increased their food intake (kcal) during intermittent HFD exposure days and compensated as a result of caloric overload during chow days. ***p<0.000 a significant between group effect, ###p<0.0000 and ##p<0.01 compared to chow controls. C) Mean (±sem) food intake during HFD exposure days was significantly higher in first two hours following access of HFD **p<0.01 a significant between group effect, and #p<0.05 compared to chow controls and D) a significant under consumption of less preferred chow was observed 12–24hr following HFD access. ***p<0.000 a significant between group effect and #p<0.05 compared to chow controls.

3.2 Intermittent HFD Exposure Attenuates Alcohol Consumption

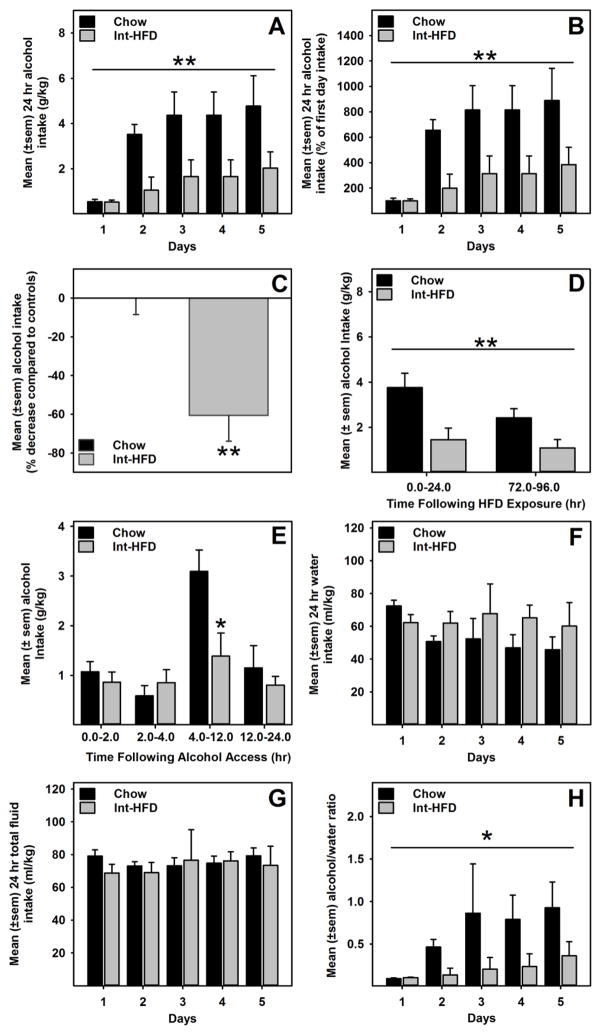

A mixed-model ANOVA revealed a main effect of time (F4, 40 = 3.918, p= 0.009) and HFD exposure (F1, 10 = 14.455, p= 0.003) (Figure 3a). We also compared mean alcohol consumption across all testing days. In this case, a univariate ANOVA revealed a main effect (F1, 10 = 14.04, p= 0.004) of HFD exposure on alcohol consumption (Figure 3c). Importantly, a mixed-model ANOVA did not find between group body weight differences during alcohol drinking sessions, suggesting that body weights (mean±sem) were not significantly different between chow (454.27±10.22) and Int-HFD (462.94 ± 9.33) group of rats. We further compared alcohol intake data immediately and 72 hr following HFD exposure. A mixed-model ANOVA identified a main effect of time (F1.0,9.0 = 15.142, p<0.01) and a significant between group effect (F1.0, 9.0 = 12.325, p<0.01), suggesting that the attenuation of alcohol intake was intact even when tested 72hr (Monday) after HFD exposure and was not different from the effects observed when testing occurred immediately after HFD exposure (Figure 3d). Alcohol intake was also assessed at various time point following the presentation of alcohol using a mixed-model ANOVA, which revealed a main effect of time (F1.62, 14.58 = 9.499, p<0.01) and a very strong trend towards significant between group effect (F1.0, 9.0 = 4.261 p=0.069). Notably, a significant (t (9) = 2.642, p<0.05) attenuation of alcohol intake occurred between 4–12hr following alcohol exposure (Figure 3e). We also analyzed water intake, total fluid (water + alcohol) intake, and alcohol/water ratio during all alcohol drinking days. While there were no statistical significant differences in water and total fluid intakes between groups (Figure 3f and g), a mixed-model ANOVA identified a significant between group effect (F1.0, 9.0 = 7.479, p<0.05) for alcohol/water ratio data, suggesting attenuated preference for alcohol in the Int-HFD access group (Figure 3h).

Figure 3. Intermittent access to a nutritionally complete high-fat diet decreases alcohol consumption in male Long-Evans rats.

Data represent mean (±sem) alcohol (20% v/v) consumption following intermittent access to a HFD and respective control groups. These testing occurred while rats were still maintained on intermittent HFD access, as outlined in the Figure 1b. A) HFD group alcohol consumption was significantly attenuated compared to chow controls. **p<0.01 main effect of HFD exposure. B) Mean (±sem) alcohol intake as a percent of the first day.. **p<0.01 main effect of HFD exposure. C) Mean (±sem) percent change in overall alcohol consumption. **p<0.01, compared to control intake. D) A similar effect (i.e., attenuation in alcohol drinking) was also seen when testing occurred on Mondays, which was 72hr following the HFD exposure. **p<0.01 main effect of HFD exposure E) Alcohol consumption was significantly attenuated 4–12hr following HFD access. *p<0.05 compared to controls. There were no changes in the water (F) or total fluid consumption (G). However, alcohol/water ratio (H) was significantly increased in the Int-HFD access group. *p<0.05 main effect of HFD exposure.

3.3 Impact of alcohol exposure on patterned feeding

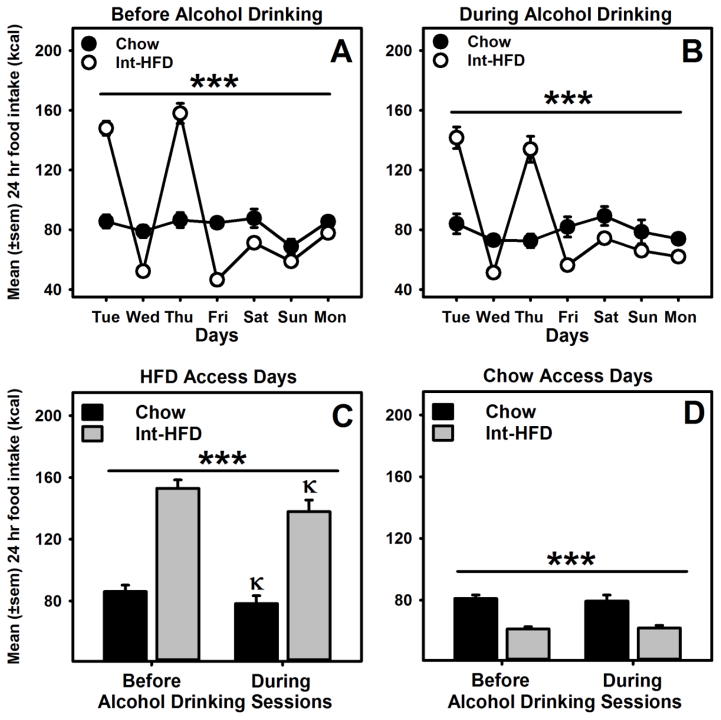

Intermittent access to HFD induced an over consumption and under consumption pattern of feeding. We compared this pattern before and during alcohol exposure and found that alcohol exposure did not alter this feeding pattern (Figure 4a and b). We further analyzed between group average energy intakes on HFD and chow access days before and during alcohol exposure using a mixed-model ANOVA and identified a main effect of alcohol exposure (F1.0, 9.0 = 21.997, p<0.01) and a significant between group effect (F1.0, 9.0 = 61.434, p<0.000) on HFD access days (Figure 4c). On the days, when rats had chow access only, a significant between group effect (F1.0, 9.0 = 33.316, p<0.000) was identified (Figure 4d). Total energy intake in both chow and Int-HFD access groups was significantly reduced on HFD access days, an effect not evident on chow days.

Figure 4. Impact of alcohol on patterned feeding in male Long-Evans rats.

Mean (±sem) weekly food intake (kcal) from chow and HFD, A) before and B) during alcohol exposure. These testing occurred while rats were still maintained on intermittent HFD access, as outlined in the Figure 1b. Rats receiving intermittent HFD access, displayed significant caloric overconsumption of HFD and voluntary caloric restriction of chow following HFD exposure days, respectively before and during alcohol exposure. ***p<0.000 a significant interaction effect. C) Mean (±sem) 24hr food intake was significantly decreased on HFD access days in both chow and Int-HFD groups during alcohol drinking sessions compared to before alcohol drinking, D) an effect not observed on chow access days. ***p<0.000 a significant main effect of diet exposure. κp<0.05 compared to the before alcohol session intake in the respective group.

3.4 Intermittent HFD Exposure does not Alter Alcohol Metabolism

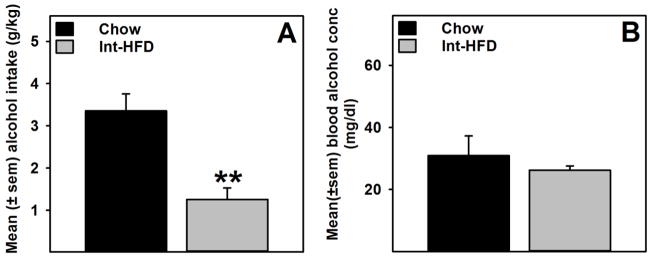

As demonstrated previously (Figure 3e), alcohol consumption was significantly (t (10) = 4.329, p<0.01) attenuated in the Int-HFD group compared to chow controls. Under these conditions, no changes in blood alcohol levels were detected between groups (Figure 5b).

Figure 5. Alcohol intake and blood alcohol concentration following intermittent access to a nutritionally complete high-fat diet in male Long-Evans rats.

Data represent mean (±sem) alcohol intake and blood alcohol concentration (BAC). These testing occurred while rats were still maintained on intermittent HFD access, as outlined in the Figure 1b. A) Alcohol consumption was significantly attenuated in the HFD group compared to chow control. **p<0.01 significantly different from chow controls. B) No change in blood alcohol levels were observed between groups when measured at the end of alcohol drinking session.

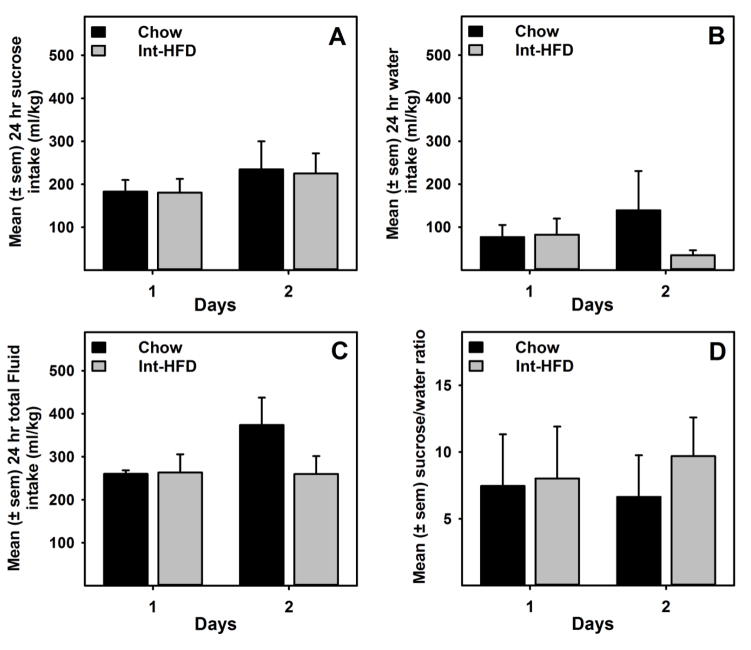

3.5 Intermittent Access to HFD does not Impact Sucrose Intake

A mixed-model ANOVA indicated no significant differences in sugar, water or total fluid intakes between chow and Int-HFD rats (Figure 6a–c). Ratio of sucrose/water was also not significantly different between groups (Figure 6d).

Figure 6. Intermittent access to a nutritionally complete high-fat diet does not affect sucrose consumption in male Long-Evans rats.

Data represent mean (±sem) sucrose (2.0% w/v) intake from HFD and respective control groups following intermittent access to HFD. These testing occurred while rats were still maintained on intermittent HFD access, as outlined in the Figure 1b.

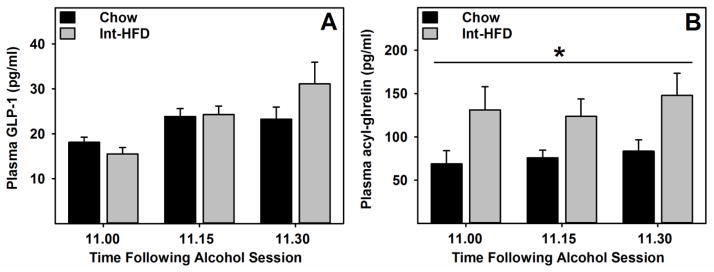

3.6 Intermittent Access to HFD Altered Feeding Peptides

A mixed-model ANOVA identified a main effect of time on GLP-1 levels, however there were no differences in the plasma GLP-1 levels between groups under these conditions (Figure 7a). A mixed-model ANOVA revealed a main effect of HFD exposure (F1, 10 = 6.724, p= 0.025) on acyl-ghrelin levels, indicating that acyl-ghrelin concentration was significantly elevated in the Int-HFD access group. (Figure 7b).

Figure 7. Plasma glucagon-like peptide-1 and acyl-ghrelin concentration during alcohol drinking session in male Long-Evans rats following intermittent access to a nutritionally complete high-fat diet.

Data represent mean (±sem) A) glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and B) acyl-ghrelin concentration in plasma. These testing occurred while rats were still maintained on intermittent HFD access, as outlined in the Figure 1b. Plasma acyl-ghrelin concentration was found elevated during alcohol drinking session following intermittent access to a HFD compared to chow controls, whereas no differences in GLP-1 levels were observed between groups. *p<0.05 main effect of HFD exposure.

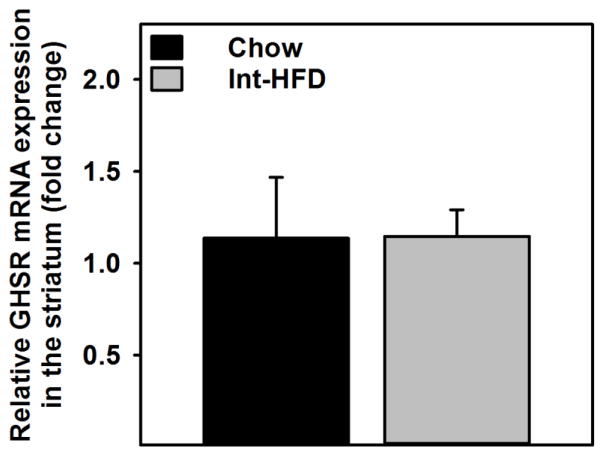

3.7 Impact of Intermittent Access to a HFD on Central GHSRs Gene Expression

No significant changes in the GHSR gene expression were observed in the ventral striatum of Int-HFD rats relative to chow controls (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Impact of Intermittent access to a nutritionally complete high-fat diet on central GHSR gene expression in male Long-Evans rats.

Mean (±sem) fold change in the mRNA expression level compared to reference gene is presented. No significant changes were observed in the striatal GHSR gene expression following intermittent access to HFD.

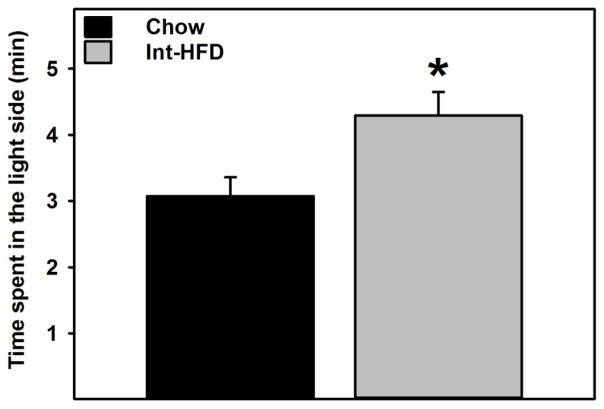

3.8 Intermittent Access to a HFD Induced Anxiolytic-like Effects

Rats in the Int-HFD group spent significantly (t (10) = 3.132, p<0.05) more time in the light side compared to chow controls (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Impact of Intermittent access to a nutritionally complete high-fat diet on anxiety-like behavior in male Long-Evans rats.

Data represent mean (±sem) time spent in the light side following intermittent access to HFD. Intermittent HFD exposure induced anxiolytic effects as rats in the HFD group spent significantly more time in the light side compared to chow controls. *p<0.05 significantly different from chow controls. These testing occurred while rats were still maintained on intermittent HFD access, as outlined in the Figure 1b.

4.0 DISCUSSION

The goal of the current study was to determine the effects of binge-like feeding behavior, induced by extended intermittent access to a HFD, on alcohol consumption. From this effort, several significant findings emerged. First, intermittent access to HFD produced a caloric binge/compensate pattern of feeding, without impacting body weight or body fat. Second, intermittent access to HFD attenuated the alcohol consumption, which was not due to overall hedonic deficits. Finally, intermittent HFD exposure induced increases in plasma ghrelin levels and anxiolytic behavior. Overall, these data suggest that binge-like intake of HFD attenuates alcohol consumption, potentially through modulating feeding peptides and anxiety-like behavior.

We and others have previously shown that intermittent access to HFD induces alternating bouts of caloric overconsumption and voluntary restriction, hallmark of binge-like eating (Corwin and Babbs, 2012; Corwin RL, 2004; Davis et al., 2007). Since the main goal of the present study was to evaluate the impact of binge-like feeding on alcohol intake, HFD in the present study was provided in an intermittent fashion. Notably, our feeding paradigm is distinct from ad libitum protocols that induce acute bouts of caloric overconsumption, which are not sustained and leads to increase in body weight. In our paradigm, rats display sustained bouts of hyperphagia (chow+HFD) but no body weight gain; therefore, our results are not confounded by the presence of an obese phenotype.

Previous studies assessing the impact of fat intake and alcohol consumption in rodents have obtained mixed and inconsistent results. Some observed high alcohol intake in fat-preferring rats, following high-fat diet exposure or injection of dietary lipids (Barson et al., 2009; Carrillo et al., 2004; Krahn and Gosnell, 1991), while others reported no correlation (Prasad et al., 1993) or blunted alcohol intake (Takase et al., 2016). However, to our knowledge, this is the first examination of alcohol intake following prolonged episodes of binge-like feeding of a nutritionally complete high-fat diet. It is important to note that several critical experimental variables could impact alcohol consumption following dietary manipulations. First, previous work investigating alcohol intake following high-fat diet evaluated alcohol consumption once the dietary manipulation had been released (Krahn and Gosnell, 1991). Notably, removal from intermittent sugar or fat access produces fundamentally different behavioral states (Avena et al., 2009). Specifically, rats given intermittent access to sugar experience withdrawal-like symptoms (Avena, 2007). In contrast, exposure to high-fat diet does not induce withdrawal-like symptoms in rodents (Bocarsly et al., 2011). Importantly, rats exposed to a HFD in the present study displayed decreased anxiety-like behavior, the opposite of that reported during withdrawal from sugar or alcohol (Avena et al., 2009; Van Skike et al., 2015). Furthermore, it is also critical to consider that observations of high-fat diet enhancing alcohol intake were made in rats that were selected based on their inherent propensity to consume high-fat diet (Krahn and Gosnell, 1991). Thus, self-selecting rats that consume elevated levels of high-fat diet could have isolated a phenotype genetically prone to consume more calories or rewards per se, independent of the source (i.e. from food or alcohol). Interestingly, clinical data suggest a bidirectional positive relationship between alcohol and energy-rich foods. High alcohol intake has been shown to be associated with higher intake of calorie-rich foods (e.g., animal products, cheese, bread and potatoes etc.) and reduced consumption of low-calorie foods (e.g., fruits and vegetables) (Herbeth et al., 1988; Kesse et al., 2001; Männistö et al., 1997). In our studies, we did not self-select rats based on diet consumption. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the length and exposure history of a calorie-rich food can have fundamentally different behavioral outcomes (Krishna et al., 2016; Tracy et al., 2015). For example, short-term access to a palatable food has been shown to induce anxiolytic behavior and increase in food motivation, whereas increase in anxiety-like behavior and decrease in food motivation has been reported following chronic HFD exposure in rodents (Davis et al., 2008; la Fleur et al., 2007; Sharma et al., 2012; Ulrich-Lai et al., 2010). In addition, chronic unlimited availability of HFD induces obesity, anhedonia and increase in anxiety-like behavior which were absent in the current study following chronic but intermittent availability of HFD. It is important to consider that HFD in the present study was provided in an intermittent fashion and behavioral changes induced by binge-like intake of palatable foods are absent when the same food is consumed in a non-binge manner (Corwin and Babbs, 2012). Therefore, it would be interesting to evaluate if the HFD alone and/or its intermittent availability are responsible for the observed effects on alcohol intake. Overall, multiple factors appear to govern the effects of food intake on behavioral processes that could regulate alcohol consumption and further studies are needed to explore these important links. Nevertheless, the present study has identified a feeding paradigm, which attenuated alcohol drinking without impacting body weight or fat content, and could have important clinical implications.

It is important to note that rats in the Int-HFD group received alcohol exposure at a time in which they were voluntarily restricting their chow/calorie intake. Under these conditions, we measured alcohol consumption at multiple time points following initiation of alcohol exposure to determine if caloric overload or hedonic deficits following HFD exposure may have played a role in the observed decreased alcohol intake. Previous studies using similar intermittent two-bottle access paradigm have shown that rats would consume ~20–30% of total 24hr session ethanol amount within first 30min of access (Carnicella et al., 2014; Simms et al., 2008). Unfortunately, we did not measure alcohol intake within 30min, however control rats in the present study consumed ~20% of total 24hr alcohol amount within 2hr following alcohol access, which is consistent with the overall observation. Interestingly, intermittent HFD exposure did not influence initiation of drinking but rather maintenance once drinking had ensued. Int-HFD rats consumed equivalent amounts of alcohol for the first 4hr of alcohol presentation, whereas a decrease in alcohol consumption was observed over the next 8hr relative to controls (Figure 3e). These data suggest post-ingestive processes that occur secondary to alcohol ingestion may control HFD effect on alcohol intake. If HFD exposure altered taste perception, we would have expected to observe decreases in alcohol intake at acute time points (i.e., over first 4 hr). Thus, the observation of decreased alcohol intake over the 4–12 hr time frame rules out the possibility of altered taste perception.

In addition, no significant changes were observed in water or total fluid consumption between groups at any time when alcohol or sugar drinking was evaluated. However, an attenuated alcohol preference was observed in the Int-HFD group as evidenced by decreased alcohol/water ratio in Int-HFD group during alcohol drinking sessions (Figure 3h). We made an equally interesting observation that alcohol exposure reduced 24 hr food intake in both chow and Int-HFD groups on HFD access days (Figure 4c). It is important to note that alcohol testing occurred when all rats had chow access only (Figure 1b) and alcohol drinking and HFD exposure occurred on alternating days during alcohol drinking sessions. This raises the possibility that decreased 24hr food intake could be a result of acute alcohol exposure. Alcohol can exert multiple and complex effects on appetite and energy balance. While moderate alcohol intake may lead to short-term increase in food consumption acutely, opposite effects have been observed following chronic consumption (Christiansen et al., 2016; Kokavec, 2008; Yeomans, 2010; Yeomans et al., 2003). However, we observed decreases, instead of increase, in food intake on HFD access days only. It is pertinent to mention here that rats in the Int-HFD displayed voluntary caloric restriction following HFD access days, which could be a result of caloric overconsumption or an attempt to selectively feed from the palatable diet. Considering the latter point, it is possible that food restriction on non-alcohol drinking days during alcohol testing (Figure 4c) occurred because of anticipation of alcohol reward on the next day, an effect observed in both groups. Although, restraining calories, rats in the Int-HFD access groups still consumed significantly higher calories on HFD access days, which could have contributed to reduced alcohol intake compared to chow controls. Interestingly, excess alcohol consumption/preference has been associated with poor adherence to dietary guidelines and dietary-restraint, which may promote problematic drinking behavior (Valencia-Martín et al., 2011; Yeomans et al., 2003) and may contribute to eating disorders and AUDs co-morbidity. Therefore, data obtained from this study might have important clinical implications to curb problematic alcohol intake. In this regard, blood alcohol concentration did not differ between treatment groups indicating that HFD exposure did not alter the metabolism of alcohol or its absorption within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (Figure 5b).

GI peptides regulate the intake and reinforcing properties of food and alcohol by acting within the brain reward circuitry (Egecioglu et al., 2013; Shirazi et al., 2013; Vadnie et al., 2014). Specifically, previous reports from our lab and others, indicate that GLP-1 and ghrelin are capable of influencing alcohol intake (Davis et al., 2012; Leggio et al., 2012; Shirazi et al., 2013). GLP-1, a hormone produced in the GI tract and brain, is stimulated by nutrients intake (Perfetti and Merkel, 2000), and decreases palatable food (Alhadeff et al., 2012; Dickson et al., 2012) and alcohol intake in rodents (Davis et al., 2012; Shirazi et al., 2013). However, we did not detect differences in plasma GLP-1 between groups (Figure 7a).

In contrast to GLP-1, ghrelin is a gut-derived peptide that stimulates feeding in rodents and humans (Kanoski et al., 2013; Skibicka et al., 2011; Tschöp et al., 2001). Ghrelin is also elevated in abstinent alcoholics (Leggio et al., 2012) and exogenous ghrelin stimulates alcohol craving in patients and rodents (Jerlhag et al., 2009; Leggio et al., 2012). In relation to alcohol intake, the majority of data collected so far indicate a positive relationship between ghrelin and alcohol intake (Jerlhag et al., 2009; Leggio et al., 2014; Vadnie et al., 2014). Interestingly, rats in the HFD exposure group displayed significantly elevated basal levels of acyl-ghrelin (Figure 7b), the active form of ghrelin (Kirchner et al., 2009), even though they consumed less alcohol. In fact, this surprising finding is in agreement with a recent report, which indicates that activity of the central ghrelin receptor (GHSR) but not increases in circulating ghrelin, stimulates alcohol intake in rodents (Jerlhag et al., 2014). It is possible that decreased GHSR signaling may underlie the decreased alcohol intake observed following HFD exposure. Thus, we measured GHSR gene expression in the ventral striatum in brain collected from control and Int-HFD rats. However, no significant changes were observed between groups (Figure 8). Therefore, the observed elevations of acyl-ghrelin do not seem to impact GHSR expression levels in brain regions linked to hedonic processes that regulate alcohol consumption. However, given the high degree of constitutive activity displayed by GHSR (Holst et al., 2003), it is possible that a decrease in receptor sensitivity may explain reduced alcohol intake secondary to HFD exposure, a future direction for studies of this type.

Typically, ghrelin levels increase during fasting and fall after nutrient exposure (Cummings, 2006; le Roux et al., 2005) raising the possibility that the increased acyl-ghrelin levels may reflect voluntary restriction from chow that occurred following HFD exposure. Importantly, our measurement of acyl-ghrelin occurred around the time when both groups had consumed approximately equal number of calories (Figure 2D). Therefore, it is unlikely that increased acyl-ghrelin we observed was due to nutrient restriction. An alternative explanation is that acyl-ghrelin levels are elevated in plasma to prepare Int-HFD rats for the large caloric load they consume during HFD exposure periods. Relevant to this topic, recent clinical work indicates that alcohol consumption reduces ghrelin levels induced by fasting in patients that are social drinkers (Leggio et al., 2013). When we detected increases in acyl-ghrelin, chow rats had consumed nearly twice as much alcohol as Int-HFD rats (Figure 3e). Therefore, the possibility exists that differences in alcohol intake may have reduced acyl-ghrelin to a greater degree in chow rats than Int-HFD rats resulting in the observed differences in acyl-ghrelin levels.

The increased plasma ghrelin we observed could be related to the decreased anxiety-like behavior we detected after HFD exposure. Prior reports indicate that ghrelin reduces activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Spencer et al., 2015, 2012), thereby reducing psychological stress. Moreover, mice that lack the ghrelin receptor display exaggerated behavioral responses to stress, and exogenous ghrelin application in mice reduces the depressive-like behavioral symptoms observed after chronic stress (Lutter et al., 2008). Thus, the increased acyl-ghrelin after intermittent HFD exposure could explain reduced anxiety in the Int-HFD group. Importantly, sensitivity to anxiety is considered as a risk-factor for the development of AUD (DeMartini and Carey, 2011; Schmidt et al., 2007) and a positive association has been reported between anxiety-like behavior and ethanol consumption (Izídio and Ramos, 2007). In the present study, intermittent HFD exposure induced an anxiolytic behavior (Figure 9). Interestingly, recent studies demonstrate that short-term access to palatable foods decrease activity of the central stress response and induce anxiolytic behavior (Mizunoya et al., 2013; Ulrich-Lai et al., 2010). There data are in agreement with a recent report from our lab in which we have shown that a similar short-term HFD exposure induced anxiolytic effects, independent of reduced alcohol drinking (Sirohi et al., 2016). It is important to note that the intermittent access to HFD did not alter body weight or body fat in the present study, which signifies that palatable food intake, without confounds present in the context of obesity, induce an anxiolytic state.

5.0 CONCLUSION

In summary, the present data indicate that dietary influences on alcohol consumption are complex, unequivocal, dependent upon the particular macronutrient in question, and presence or absence of the dietary intervention when evaluating alcohol intake. Our data suggest that binge-like intake of high-fat diet that includes alternation between voluntary nutrient restriction and caloric overconsumption decreases alcohol intake; an effect unexplained by flux in GI peptides or decreases in overall hedonic state. Instead, anxiolytic effects, a process controlled by GI peptides, could be integral for the decrease of alcohol intake following binge-like feeding behavior. As we are just beginning to understand how brain integrates metabolic information to control alcohol intake, studies of this type provide fundamental insights that can help explain how feeding behavior can influence processes that contribute to development of AUD.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Intermittent high-fat diet (Int-HFD) access selectively attenuated alcohol intake.

Int-HFD intake increased plasma ghrelin levels and induced anxiolytic behavior.

Altered anxiety levels due to Int-HFD exposure may have impacted alcohol intake.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported, in part, by Alcohol and Drug Abuse Program (ADARP) at Washington State University grant # 2550-1324 to JFD. This publication was also made possible by funding, in part, from the NIMHD-RCMI grant number 5G12MD007595 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and the NIGMS-BUILD grant number 8UL1GM118967 to SS. We thank Cody Kowalski, Anthony Burger and Angela Williams for technical assistance.

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alhadeff AL, Rupprecht LE, Hayes MR. GLP-1 neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract project directly to the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens to control for food intake. Endocrinology. 2012;153:647–58. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attia E, Becker AE, Bryant-Waugh R, Hoek HW, Kreipe RE, Marcus MD, Mitchell JE, Striegel RH, Walsh BT, Wilson GT, Wolfe BE, Wonderlich S. Feeding and eating disorders in DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1237–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avena NM. Examining the addictive-like properties of binge eating using an animal model of sugar dependence. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:481–91. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avena NM, Carrillo CA, Needham L, Leibowitz SF, Hoebel BG. Sugar-dependent rats show enhanced intake of unsweetened ethanol. Alcohol. 2004;34:203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG. Sugar and fat bingeing have notable differences in addictive-like behavior. J Nutr. 2009;139:623–8. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.097584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barson JR, Karatayev O, Chang GQ, Johnson DF, Bocarsly ME, Hoebel BG, Leibowitz SF. Positive relationship between dietary fat, ethanol intake, triglycerides, and hypothalamic peptides: counteraction by lipid-lowering drugs. Alcohol. 2009;43:433–41. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barson JR, Leibowitz SF. Hypothalamic neuropeptide signaling in alcohol addiction. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;65:321–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocarsly ME, Berner LA, Hoebel BG, Avena NM. Rats that binge eat fat-rich food do not show somatic signs or anxiety associated with opiate-like withdrawal: implications for nutrient-specific food addiction behaviors. Physiol Behav. 2011;104:865–72. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchery EE, Harwood HJ, Sacks JJ, Simon CJ, Brewer RD. Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S., 2006. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:516–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Klump KL, Thornton L, Kaplan AS, Devlin B, Fichter MM, Halmi KA, Strober M, Woodside DB, Crow S, Mitchell JE, Rotondo A, Mauri M, Cassano GB, Keel PK, Berrettini WH, Kaye WH. Alcohol use disorder comorbidity in eating disorders: a multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1000–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnicella S, Ron D, Barak S. Intermittent ethanol access schedule in rats as a preclinical model of alcohol abuse. Alcohol. 2014;48:243–52. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo CA, Leibowitz SF, Karatayev O, Hoebel BG. A high-fat meal or injection of lipids stimulates ethanol intake. Alcohol. 2004;34:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterson ML, Pryor TL, Burke MJ, Morgan CD. Death due to alcoholic complications in a young woman with a severe eating disorder: a case report. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;21:303–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199704)21:3<303::aid-eat12>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen P, Rose A, Randall-Smith L, Hardman CA. Alcohol’s acute effect on food intake is mediated by inhibitory control impairments. Heal Psychol. 2016;35:518–522. doi: 10.1037/hea0000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin RLW, Babbs RK. Rodent models of binge eating: are they models of addiction? ILAR J. 2012;53:23–34. doi: 10.1093/ilar.53.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin RLBLA. Behavioral models of binge-type eating. Physiol Behav. 2004;82:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottone P, Sabino V, Steardo L, Zorrilla EP. Intermittent access to preferred food reduces the reinforcing efficacy of chow in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1066–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90309.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings DE. Ghrelin and the short- and long-term regulation of appetite and body weight. Physiol Behav. 2006;89:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JF, Melhorn SJ, Shurdak JD, Heiman JU, Tschöp MH, Clegg DJ, Benoit SC. Comparison of hydrogenated vegetable shortening and nutritionally complete high-fat diet on limited access-binge behavior in rats. Physiol Behav. 2007;92:924–30. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JF, Schurdak JD, Magrisso IJ, Mul JD, Grayson BE, Pfluger PT, Tschöp MH, Seeley RJ, Benoit SC. Gastric bypass surgery attenuates ethanol consumption in ethanol-preferring rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JF, Tracy AL, Schurdak JD, Tschöp MH, Lipton JW, Clegg DJ, Benoit SC. Exposure to elevated levels of dietary fat attenuates psychostimulant reward and mesolimbic dopamine turnover in the rat. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122:1257–1263. doi: 10.1037/a0013111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini KS, Carey KB. The role of anxiety sensitivity and drinking motives in predicting alcohol use: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:169–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson SL, Shirazi RH, Hansson C, Bergquist F, Nissbrandt H, Skibicka KP. The glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) analogue, exendin-4, decreases the rewarding value of food: a new role for mesolimbic GLP-1 receptors. J Neurosci. 2012;32:4812–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6326-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drazen DL, Vahl TP, D’Alessio DA, Seeley RJ, Woods SC. Effects of a fixed meal pattern on ghrelin secretion: evidence for a learned response independent of nutrient status. Endocrinology. 2006;147:23–30. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, Larimer ME, Neighbors C. Alcohol and drug-related negative consequences in college students with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32:171–8. doi: 10.1002/eat.10075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egecioglu E, Steensland P, Fredriksson I, Feltmann K, Engel JA, Jerlhag E. The glucagon-like peptide 1 analogue Exendin-4 attenuates alcohol mediated behaviors in rodents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:1259–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriter C, Ray LA. Binge eating and binge drinking: an integrative review. Eat Behav. 2011;12:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Dorer DJ, Keel PK, Jackson S, Manzo MP, Herzog DB. How do eating disorders and alcohol use disorder influence each other? Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38:200–7. doi: 10.1002/eat.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhardt AN, Boswell RG, White MA. The association of “food addiction” with disordered eating and body mass index. Eat Behav. 2014;15:427–33. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–34. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell ZAT, Slane JD, Klump KL. Predictors of alcohol problems in college women: the role of depressive symptoms, disordered eating, and family history of alcoholism. Addict Behav. 2009;34:252–7. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbeth B, Didelot-Barthelemy L, Lemoine A, Le Devehat C. Dietary behavior of French men according to alcohol drinking pattern. J Stud Alcohol. 1988;49:268–72. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst B, Cygankiewicz A, Jensen TH, Ankersen M, Schwartz TW. High constitutive signaling of the ghrelin receptor--identification of a potent inverse agonist. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:2201–10. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izídio GS, Ramos A. Positive association between ethanol consumption and anxiety-related behaviors in two selected rat lines. Alcohol. 2007;41:517–24. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerlhag E, Egecioglu E, Landgren S, Salomé N, Heilig M, Moechars D, Datta R, Perrissoud D, Dickson SL, Engel JA. Requirement of central ghrelin signaling for alcohol reward. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11318–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812809106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerlhag E, Ivanoff L, Vater A, Engel JA. Peripherally circulating ghrelin does not mediate alcohol-induced reward and alcohol intake in rodents. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:959–68. doi: 10.1111/acer.12337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, BJ, SJ Monitoring the Future, National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2004. Second Sch Students. 2005;I NIH Pub No 05–5727. [Google Scholar]

- Kanoski SE, Fortin SM, Ricks KM, Grill HJ. Ghrelin signaling in the ventral hippocampus stimulates learned and motivational aspects of feeding via PI3K-Akt signaling. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:915–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly-Weeder S. Binge drinking and disordered eating in college students. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2011;23:33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesse E, Clavel-Chapelon F, Slimani N, van Liere M. Do eating habits differ according to alcohol consumption? Results of a study of the French cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (E3N-EPIC) Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:322–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.3.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, Deitz AC, Hudson JI, Shahly V, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Benjet C, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Maria Haro J, Kovess-Masfety V, O’Neill S, Posada-Villa J, Sasu C, Scott K, Viana MC, Xavier M. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:904–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner H, Gutierrez JA, Solenberg PJ, Pfluger PT, Czyzyk TA, Willency JA, Schürmann A, Joost HG, Jandacek RJ, Hale JE, Heiman ML, Tschöp MH. GOAT links dietary lipids with the endocrine control of energy balance. Nat Med. 2009;15:741–5. doi: 10.1038/nm.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokavec A. Is decreased appetite for food a physiological consequence of alcohol consumption? Appetite. 2008;51:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahn DD, Gosnell BA. Fat-preferring rats consume more alcohol than carbohydrate-preferring rats. Alcohol. 1991;8:313–6. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(91)90465-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna S, Lin Z, de La Serre CB, Wagner JJ, Harn DH, Pepples LM, Djani DM, Weber MT, Srivastava L, Filipov NM. Time-dependent behavioral, neurochemical, and metabolic dysregulation in female C57BL/6 mice caused by chronic high-fat diet intake. Physiol Behav. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- la Fleur SE, Vanderschuren LJMJ, Luijendijk MC, Kloeze BM, Tiesjema B, Adan RAH. A reciprocal interaction between food-motivated behavior and diet-induced obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1286–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Roux CW, Patterson M, Vincent RP, Hunt C, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Postprandial plasma ghrelin is suppressed proportional to meal calorie content in normal-weight but not obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1068–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Cardone S, Nesci A, Miceli A, Malandrino N, Capristo E, Canestrelli B, Monteleone P, Kenna GA, Swift RM, Addolorato G. Ghrelin system in alcohol-dependent subjects: role of plasma ghrelin levels in alcohol drinking and craving. Addict Biol. 2012;17:452–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggio L, Schwandt ML, Oot EN, Dias AA, Ramchandani VA. Fasting-induced increase in plasma ghrelin is blunted by intravenous alcohol administration: a within-subject placebo-controlled study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:3085–91. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggio L, Zywiak WH, Fricchione SR, Edwards SM, de la Monte SM, Swift RM, Kenna GA. Intravenous ghrelin administration increases alcohol craving in alcohol-dependent heavy drinkers: a preliminary investigation. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76:734–41. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutter M, Sakata I, Osborne-Lawrence S, Rovinsky SA, Anderson JG, Jung S, Birnbaum S, Yanagisawa M, Elmquist JK, Nestler EJ, Zigman JM. The orexigenic hormone ghrelin defends against depressive symptoms of chronic stress. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:752–3. doi: 10.1038/nn.2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Männistö S, Uusitalo K, Roos E, Fogelholm M, Pietinen P. Alcohol beverage drinking, diet and body mass index in a cross-sectional survey. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997;51:326–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, Hatsukami D, Eckert ED, Pyle RL. Characteristics of 275 patients with bulimia. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:482–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizunoya W, Ohnuki K, Baba K, Miyahara H, Shimizu N, Tabata K, Kino T, Sato Y, Tatsumi R, Ikeuchi Y. Effect of dietary fat type on anxiety-like and depression-like behavior in mice. Springerplus. 2013;2:165. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morganstern I, Barson JR, Leibowitz SF. Regulation of drug and palatable food overconsumption by similar peptide systems. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4:163–73. doi: 10.2174/1874473711104030163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perello M, Valdivia S, García Romero G, Raingo J. Considerations about rodent models of binge eating episodes. Front Psychol. 2014;5:372. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti R, Merkel P. Glucagon-like peptide-1: a major regulator of pancreatic beta-cell function. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;143:717–25. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1430717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad A, Abadie JM, Prasad C. Can dietary macronutrient preference profile serve as a predictor of voluntary alcohol consumption? Alcohol. 1993;10:485–9. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(93)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Buckner JD, Keough ME. Anxiety Sensitivity As a Prospective Predictor of Alcohol Use Disorders. Behav Modif. 2007;31:202–219. doi: 10.1177/0145445506297019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Fernandes MF, Fulton S. Adaptations in brain reward circuitry underlie palatable food cravings and anxiety induced by high-fat diet withdrawal. Int J Obes. 2012;37:1183–1191. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi RH, Dickson SL, Skibicka KP. Gut peptide GLP-1 and its analogue, Exendin-4, decrease alcohol intake and reward. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms JA, Steensland P, Medina B, Abernathy KE, Chandler LJ, Wise R, Bartlett SE. Intermittent access to 20% ethanol induces high ethanol consumption in Long-Evans and Wistar rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1816–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirohi S, Van Cleef A, Davis JF. Binge-like intake of HFD attenuates alcohol intake in rats. Physiol Behav. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skibicka KP, Hansson C, Alvarez-Crespo M, Friberg PA, Dickson SL. Ghrelin directly targets the ventral tegmental area to increase food motivation. Neuroscience. 2011;180:129–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonneville KR, Horton NJ, Micali N, Crosby RD, Swanson SA, Solmi F, Field AE. Longitudinal associations between binge eating and overeating and adverse outcomes among adolescents and young adults: does loss of control matter? JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:149–55. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SJ, Emmerzaal TL, Kozicz T, Andrews ZB. Ghrelin’s Role in the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Stress Response: Implications for Mood Disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SJ, Xu L, Clarke MA, Lemus M, Reichenbach A, Geenen B, Kozicz T, Andrews ZB. Ghrelin regulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and restricts anxiety after acute stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:457–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takase K, Tsuneoka Y, Oda S, Kuroda M, Funato H. High-fat diet feeding alters olfactory-, social-, and reward-related behaviors of mice independent of obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016 doi: 10.1002/oby.21441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Striatocortical pathway dysfunction in addiction and obesity: differences and similarities. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;48:1–19. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2012.735642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong J, D’Alessio D. Eating disorders and gastrointestinal peptides. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2011;18:42–9. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e328341e12b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy AL, Wee CJM, Hazeltine GE, Carter RA. Characterization of attenuated food motivation in high-fat diet-induced obesity: Critical roles for time on diet and reinforcer familiarity. Physiol Behav. 2015;141:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschöp M, Weyer C, Tataranni PA, Devanarayan V, Ravussin E, Heiman ML. Circulating ghrelin levels are decreased in human obesity. Diabetes. 2001;50:707–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.4.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich-Lai YM, Christiansen AM, Ostrander MM, Jones AA, Jones KR, Choi DC, Krause EG, Evanson NK, Furay AR, Davis JF, Solomon MB, de Kloet AD, Tamashiro KL, Sakai RR, Seeley RJ, Woods SC, Herman JP. Pleasurable behaviors reduce stress via brain reward pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20529–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007740107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadnie CA, Park JH, Abdel Gawad N, Ho AMC, Hinton DJ, Choi DS. Gut-brain peptides in corticostriatal-limbic circuitry and alcohol use disorders. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:288. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahl TP, Drazen DL, Seeley RJ, D’Alessio DA, Woods SC. Meal-anticipatory glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion in rats. Endocrinology. 2010;151:569–75. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Martín JL, Galán I, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. The association between alcohol consumption patterns and adherence to food consumption guidelines. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:2075–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Skike CE, Diaz-Granados JL, Matthews DB. Chronic intermittent ethanol exposure produces persistent anxiety in adolescent and adult rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:262–71. doi: 10.1111/acer.12617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Tomasi D, Baler R. Food and drug reward: overlapping circuits in human obesity and addiction. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2012;11:1–24. doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe BE, Baker CW, Smith AT, Kelly-Weeder S. Validity and utility of the current definition of binge eating. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:674–86. doi: 10.1002/eat.20728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans MR. Alcohol, appetite and energy balance: Is alcohol intake a risk factor for obesity? Physiol Behav. 2010;100:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans MR, Blundell JE, Leshem M. Palatability: response to nutritional need or need-free stimulation of appetite? Br J Nutr. 2004;92(Suppl 1):S3–14. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans MR, Caton S, Hetherington MM. Alcohol and food intake. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003;6:639–44. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000098088.40916.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]