Abstract

Objective

In many resource-limited settings, people from rural areas migrate to urban hubs in search of work. Thus, urban public-sector HIV clinics in South Africa (SA) often cater to both local residents and patients from other provinces and/or countries. The objective of this analysis was to compare programmatic treatment outcomes by citizenship status in an urban clinic in SA.

Setting

An urban public-sector HIV treatment facility in Johannesburg, SA.

Participants

We included all antiretroviral therapy (ART)-naïve, non-pregnant patients who initiated standard first-line treatment from January 2008 to December 2013. 12 219 patients were included and 59.5% were women.

Primary outcome measure

Patients were followed from ART initiation until death, transfer, loss to follow-up (LTF), or data set closure. We describe attrition (mortality and LTF) stratified by SA citizenship status (confirmed SA citizens (with national ID number), unconfirmed SA citizens (no ID), and foreign nationals) and model the risk of attrition using Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results

70% of included patients were confirmed SA citizens, 19% were unconfirmed SA citizens, and 11% were foreign nationals. Unconfirmed SA citizens were far more likely to die or become LTF than other patients. A similar proportion of foreign nationals (18.2%) and confirmed SA citizens (17.7%) had left care at 1 year compared with 47.0% of unconfirmed SA citizens (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) unconfirmed SA vs confirmed SA: 2.68; 95% CI 2.42 to 2.97). By the end of follow-up, 75.5% of unconfirmed SA citizens had left care, approximately twice that of any other group.

Conclusions

Unconfirmed SA citizens were more likely to drop out of care after ART initiation than other patients. Further research is needed to determine whether this observed attrition is representative of migration and/or self-transfer to another HIV clinic as such high rates of attrition pose challenges for the success of the national ART programme.

Keywords: loss to follow-up, mortality, attrition, citizenship, resource-limited settings

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We used data from a single urban public-sector HIV treatment facility located within a tertiary hospital which may limit generalisability.

There may be some exposure misclassification as some foreign nationals may be incorrectly recorded as self-reported South African citizens without a national ID number.

We do not have information on migration patterns of individuals included in the study and can only speculate as to whether loss from care is indicative of population mobility.

The study site uses a comprehensive electronic medical record in which laboratory results are uploaded directly into the system from the National Health Laboratory Service, reducing opportunities for missing data and/or data entry errors.

Routine loss to follow-up tracing mitigates loss from antiretroviral therapy care.

Introduction

South Africa has one of the largest economies on the African continent, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), eclipsed only by Nigeria.1 As such, people from all over the continent, and especially sub-Saharan Africa, migrate to South Africa in search of employment.2–4 Within South Africa itself internal migration is common as residents of rural areas move to urban hubs or mining communities in hopes of improving their economic prospects.3–5 As a result, public-sector antiretroviral therapy (ART) programmes in urban centres such as Johannesburg cater to a wide variety of patients who migrated from all over South Africa and the continent.

On the basis of the results from the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 052 study, which found that earlier initiation of ART for treatment of HIV resulted in a 96% reduction in the risk of transmission to an uninfected partner, the concept of using antiretroviral treatment as HIV prevention has gained in popularity.6 However, in order for treatment as prevention to have an impact on population-level transmission and incidence, retention in HIV treatment programmes must remain high.7 8 As a result, identifying patients at high risk of loss to follow-up is of utmost importance in order to target interventions that are most likely to succeed in retaining them in care.

Previous research has shown that while foreigners and/or migrants often experience as good clinical outcomes in HIV care as local residents, their risk of loss from care has been variable. Results from a study comparing outcomes among self-reported foreigners to self-reported South Africans in Johannesburg found that foreigners were less likely to have died or become lost to follow-up than South Africans (3.8% vs 12.8%).9 However, recent migrants in KwaZulu-Natal were 53% more likely to disengage from care than long-term residents and migrant workers in Lesotho were over twice as likely to be lost to follow-up than non-migrant workers 3–6 months after ART initiation and more than six times as likely after more than 12 months on ART.10 11 Thus, we sought to further investigate these relationships by evaluating whether attrition (death and loss to follow-up) from a large, outpatient HIV treatment facility in Johannesburg may be related to South African citizenship status.

Methods

Study site

This analysis was conducted using data from the Themba Lethu HIV Clinic, a large urban public-sector outpatient HIV treatment facility located within the Helen Joseph Hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa. Since the roll-out of ART in the public-sector in 2004, Themba Lethu has seen ∼30 000 patients and has initiated over 20 000 of those patients on ART.12 Treatment provision at Themba Lethu follows the National Department of Health ART guidelines. Initially, treatment was offered to HIV-infected adult patients with a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 or WHO stage 3 disease.13 The eligibility threshold was increased to 350 cells/mm3 for pregnant women and patients co-infected with tuberculosis (TB) in 2010 and to all HIV-infected patients in 2011.14 15 In 2013, pregnant women, those co-infected with TB, and those with WHO stage 3 or 4 disease could initiate ART regardless of their CD4 count and in 2015, the treatment initiation threshold was raised to a CD4 count of 500 cells/mm3.16 17

While not a requirement to receive care, it is standard practice to ask all patients who present for care at Themba Lethu for their South African national identity number at their first visit. This information is collected along with other identifying details, including date of birth, country of birth, country of citizenship, physical address, and phone number. Approximately 60% of patients provide a valid ID number which can then be used to link lost to follow-up patients to the National Vital Registration System to improve ascertainment of mortality.18 For the remaining 40% of patients, vital status is primarily obtained through loss to follow-up tracing. Since 2007, loss to follow-up tracing has been a routine component of ART care at Themba Lethu. Clinic counsellors make up to three attempts to contact those patients who have missed a scheduled visit via the phone number recorded in their file. Until 2013, home-based visits may also have been conducted for patients who could not be contacted via phone. However, this service is no longer routinely available. All demographic information along with routinely collected clinical data, including ART regimens, is entered into an electronic medical record called TherapyEdge-HIV in real time by the clinician during the patient encounter. Laboratory results are downloaded directly into the system from databases maintained by the National Health Laboratory Service.12

Study population

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis using data collected prospectively as part of routine clinical care. All ART-naïve, adult (≥18 years old), non-pregnant patients who initiated a standard first-line ART regimen between January 2008 and December 2013 were included.

Study variables

The primary exposure in this study was documentation of citizenship status in the electronic medical record, using three categories: patients with a valid ID were categorised as confirmed South African if the 11th digit of the ID number identified the holder as a South African citizen (11th digit=0). Few patients with a valid ID were identified as non-South African citizens (n=196) so were excluded from further analysis. Patients without a valid ID were categorised as either unconfirmed South Africans or as foreign nationals based on their self-reported country of citizenship.

Ascertainment of mortality as a reason for loss to follow-up (≥3 months late for a scheduled visit) is easier among patients with a valid South African ID number due to regular linkage to the National Vital Registration System. Thus, our primary outcome was attrition, defined as death and loss to follow-up combined, rather than mortality alone, as deceased patients without an ID whose death was not reported to the clinic would appear as lost to follow-up.

Patients were included in the analysis if they initiated a standard first-line ART regimen, defined as stavudine (d4T), zidovudine (AZT), or tenofovir (TDF), in combination with lamivudine (3TC) and efavirenz (EFV) or nevirapine (NVP). Patients on TDF could also have been prescribed emtricitabine (FTC) in place of 3TC.13 14 The CD4 count recorded closest to ART initiation from 6 months prior to the date of ART initiation to 7 days after was considered to be the baseline CD4 count value. CD4 count was then categorised as <50, 50–99, 100–199 and ≥200 cells/mm3. Standard categories were used for body mass index (BMI) and anaemia was defined according to standards set by the WHO as severe (<8 g/dL), moderate (8–10 g/dL), mild (men: 11–12 g/dL; women: 11 g/dL), or none (men: ≥13 g/dL; women: ≥12 g/dL).19

Statistical analysis

Patients were followed from the date of ART initiation until the earliest of death, loss to follow-up, transfer to another HIV treatment facility, or closing of the data set (28 February 2015). We present baseline demographic and clinical characteristics as simple proportions for categorical variables and as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables. Crude Kaplan-Meier curves depicting the probability of remaining in care over time by 12 months and ever after ART initiation are presented stratified by citizenship status. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate the association between citizenship status and the risk of attrition using a complete case analysis. Results are presented as hazard ratios (HR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Age, sex and baseline CD4 count category were included as covariates in the adjusted model. Other baseline characteristics that were considered to be plausible confounders, including year of ART initiation, employment status, BMI, WHO stage, presence and severity of anaemia, TB co-infection, and baseline ART regimen, and were associated with both citizenship status and attrition (p<0.2) in crude analyses were also included.

As an additional analysis, we used multiple imputation using chained equations (MICE) to account for missing data on baseline CD4 count (6.5%), haemoglobin (8.4%), BMI (15.1%), and employment status (3.0%) and present these results in the accompanying online supplementary appendix.

bmjopen-2016-013908supp_appendix.pdf (608.5KB, pdf)

Results

In total, 12 291 patients initiated a standard, first-line ART regimen between January 2008 and December 2013 and were included in this analysis. Of these, 59.5% were women, the median (IQR) age at ART initiation was 37.6 (31.7–44.4) years and the median (IQR) baseline CD4 count was 120 (46–195) cells/mm3. Approximately 70% of patients were classified as confirmed South African citizens. Of the remaining 30% (n=3685), 62% were unconfirmed South African citizens who did not report an ID number and the remaining 38% self-identified as foreign nationals. Patients were followed for a median (IQR) of 28.4 (9.6–48.6) months from the date of ART initiation.

Unconfirmed citizens had poor clinical characteristics at baseline. They were more likely to have severe anaemia (12.1%), WHO stage III or IV disease (51.8%), and be co-infected with TB (14.8%) than both confirmed citizens (severe anaemia: 8.0%; WHO stage III or IV disease: 41.5%; TB co-infection: 12.1%) and foreign nationals (severe anaemia: 6.7%; WHO stage III or IV disease: 32.6%; TB co-infection: 6.6%). Compared with foreign nationals, unconfirmed citizens also had a slightly lower median baseline CD4 count (101 vs 137), and were less likely to be employed (45.9% vs 58.6%) while foreign nationals were more likely to be under the age of 35 (53.6%) than confirmed (35.1%) and unconfirmed (43.5%) citizens (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who initiated ART between January 2008 and December 2013 at the Themba Lethu Clinic in Johannesburg South Africa, stratified by documentation of South African citizenship

| Characteristic | Total | Confirmed South African citizen | Unconfirmed South African citizen | Foreign national |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 12 219 | 8534 | 2292 | 1393 |

| Year of ART initiation | ||||

| 2008–2009 | 4133 (33.8%) | 2927 (34.3%) | 985 (43.0%) | 221 (15.9%) |

| 2010–2011 | 4791 (39.2%) | 3324 (39.0%) | 848 (37.0%) | 619 (44.4%) |

| 2012–2013 | 3295 (27.0%) | 2283 (26.8%) | 459 (20.0%) | 553 (39.7%) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 4943 (40.5%) | 3346 (39.2%) | 1001 (43.7%) | 596 (42.8%) |

| Female | 7276 (59.5%) | 5188 (60.8%) | 1291 (56.3%) | 797 (57.2%) |

| Age at ART initiation | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 37.6 (31.7–44.4) | 38.4 (32.4–45.4) | 36.5 (30.8–44.0) | 34.3 (30.1–39.4) |

| <30 | 2227 (18.2%) | 1390 (16.3%) | 499 (21.8%) | 338 (24.3%) |

| 30–34.9 | 2511 (20.6%) | 1605 (18.8%) | 498 (21.7%) | 408 (29.3%) |

| 35–39.9 | 2610 (21.4%) | 1826 (21.4%) | 457 (19.9%) | 327 (23.5%) |

| 40–44.9 | 1993 (16.3%) | 1482 (17.4%) | 336 (14.7%) | 175 (12.6%) |

| ≥45 | 2878 (23.6%) | 2231 (26.1%) | 502 (21.9%) | 145 (10.4%) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Missing | 370 (3.0%) | 222 (2.6%) | 97 (4.2%) | 51 (3.7%) |

| Employed | 6691 (54.8%) | 4822 (56.5%) | 1053 (45.9%) | 816 (58.6%) |

| Unemployed | 5158 (42.2%) | 3490 (40.9%) | 1142 (49.8%) | 526 (37.8%) |

| Baseline CD4 count (cells/mm3) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 120 (46–195) | 122 (48–197) | 101 (35–178) | 137 (58.5–210) |

| Missing | 789 (6.5%) | 484 (5.7%) | 188 (8.2%) | 117 (8.4%) |

| <50 | 2991 (24.5%) | 2047 (24.0%) | 664 (29.0%) | 280 (20.1%) |

| 50–99 | 1947 (15.9%) | 1366 (16.0%) | 373 (16.3%) | 208 (14.9%) |

| 100–199 | 3791 (31.0%) | 2683 (31.4%) | 680 (29.7%) | 428 (30.7%) |

| ≥200 | 2701 (22.1%) | 1954 (22.9%) | 387 (16.9%) | 360 (25.8%) |

| BMI at ART initiation (kg/m2) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 21.8 (19.3–25.3) | 22.0 (19.3–25.7) | 20.8 (18.6–23.8) | 21.9 (19.7–24.9) |

| Missing | 1839 (15.1%) | 1088 (12.8%) | 497 (21.7%) | 254 (18.2%) |

| <18.5 | 1918 (15.7%) | 1328 (15.6%) | 432 (18.9%) | 158 (11.3%) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 5707 (46.7%) | 3990 (46.8%) | 1006 (43.9%) | 711 (51.0%) |

| 25–29.9 | 1812 (14.8%) | 1364 (16.0%) | 240 (10.5%) | 208 (14.9%) |

| ≥30 | 943 (7.7%) | 764 (9.0%) | 117 (5.1%) | 62 (4.5%) |

| WHO stage | ||||

| I/II | 7037 (57.6%) | 4993 (58.5%) | 1105 (48.2%) | 939 (67.4%) |

| III/IV | 5182 (42.4%) | 3541 (41.5%) | 1187 (51.8%) | 454 (32.6%) |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) at ART initiation | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 11.1 (9.5–12.6) | 11.2 (9.6–12.6) | 10.5 (8.9–12.2) | 11.3 (9.8–12.8) |

| Anaemia at ART initiation | ||||

| Missing | 1027 (8.4%) | 623 (7.3%) | 262 (11.4%) | 142 (10.2%) |

| No anaemia | 3025 (24.8%) | 2223 (26.1%) | 420 (18.3%) | 382 (27.4%) |

| Mild anaemia | 2658 (21.8%) | 1892 (22.2%) | 457 (19.9%) | 309 (22.2%) |

| Moderate anaemia | 4455 (36.5%) | 3113 (36.5%) | 875 (38.2%) | 467 (33.5%) |

| Severe anaemia | 1054 (8.6%) | 683 (8.0%) | 278 (12.1%) | 93 (6.7%) |

| Co-infected with tuberculosis at ART initiation | ||||

| Yes | 1464 (12.0%) | 1034 (12.1%) | 338 (14.8%) | 92 (6.6%) |

| First ART regimen* | ||||

| TDF-3TC-EFV | 5576 (45.6%) | 3839 (45.0%) | 914 (39.9%) | 823 (59.1%) |

| d4T-3TC-EFV | 4918 (40.3%) | 3481 (40.8%) | 1111 (48.5%) | 326 (23.4%) |

| AZT-3TC-EFV | 286 (2.3%) | 202 (2.4%) | 61 (2.7%) | 23 (1.7%) |

| Other | 1439 (11.8%) | 1012 (11.9%) | 206 (9.0%) | 221 (15.9%) |

*3TC: lamivudine; AZT: zidovudine; d4T: stavudine; EFV: efavirenz; TDF: tenofovir; Other regimens are: TDF-3TC-NVP (nevirapine), AZT-3TC-NVP, TDF-EMT (emtricitabine)-EFV, TDF-EMT-NVP, and d4T-3TC-NVP.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; BMI, body mass index.

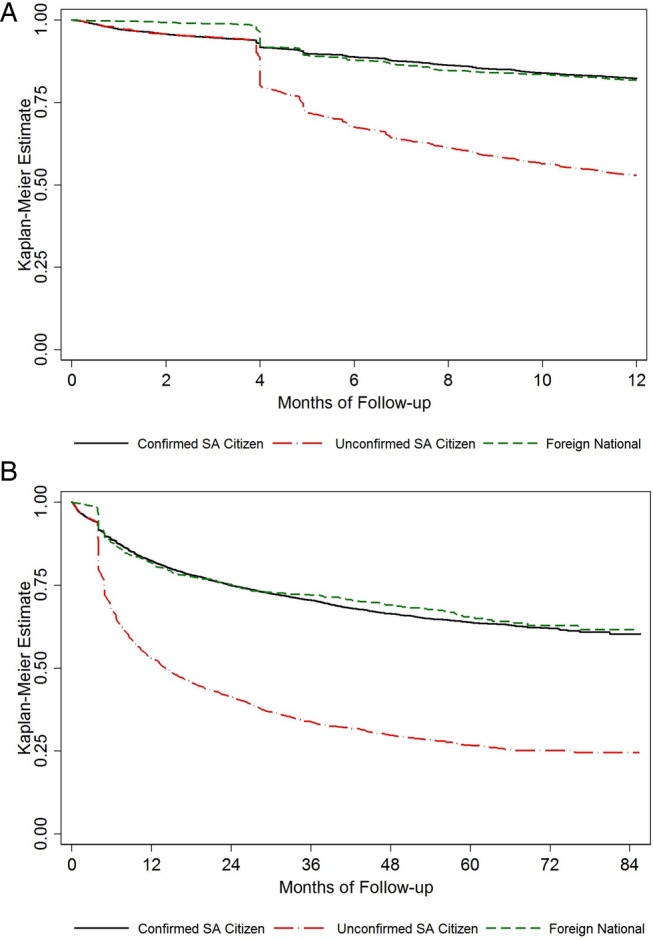

Unconfirmed South African citizens were far more likely to be dead or lost to follow-up at both 12 months and ever after ART initiation compared with all other patients. Using Kaplan-Meier analysis, 17.7% of confirmed citizens and 18.2% of foreign nationals had died or were lost to follow-up after 12 months on ART, compared with 47.0% of unconfirmed citizens. Likewise by the end of follow-up, 75.5% of unconfirmed citizens had died or dropped out of care, which was approximately twice the attrition experienced by any other group (figure 1). However, we note that because individuals without a national ID number cannot be linked to the national vital registration system, we cannot determine how much of this increase is related to death and how much is related to loss from care.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve depicting time to death or loss to follow-up at (A) 12 months after and (B) ever after antiretroviral therapy initiation among patients who initiated antiretroviral therapy between January 2008 and December 2013, stratified by South African (SA) citizenship status.

This relationship was explored further in both unadjusted and adjusted regression models. In total, 9451 patients had information available on all covariates of interest and were included in the models. Compared with confirmed South African citizens, at 12 months, unconfirmed South African citizens were almost three times as likely to die or drop out of care (HR 2.94; 95% CI 2.66 to 3.25), while a small protective effect was observed for foreign nationals (HR 0.89; 95% CI 0.74 to 1.06). The association was attenuated slightly when adjusted for baseline demographic and clinical characteristics but unconfirmed citizens remained over two and a half times more likely to have died or left care compared with confirmed citizens (aHR 2.68; 95% CI 2.42 to 2.97). By the end of follow-up, the increased risk for attrition from care remained for unconfirmed citizens (aHR 2.68; 95% CI 2.47 to 2.90) while a small protective effect continued to be observed for foreign nationals (aHR 0.88; 95% CI 0.77 to 1.00) (table 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted estimates of attrition (death and LTF) at 1 year and ever after ART initiation among 9451 patients who initiated ART between January 2008 and December 2013 at the Themba Lethu Clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa

| Characteristic | 1-year after ART initiation |

Ever after ART initiation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead or LTF/N (%) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Dead or LTF/N (%) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |

| Citizenship status | ||||||

| Confirmed South African citizen | 1019/6822 (14.9%) | Reference | Reference | 1967/6822 (28.8%) | Reference | Reference |

| Unconfirmed South African citizen | 605/1616 (37.4%) | 2.94 (2.66 to 3.25) | 2.68 (2.42 to 2.97) | 959/1616 (59.3%) | 2.92 (2.70 to 3.15) | 2.68 (2.47 to 2.90) |

| Foreign national | 138/1013 (13.6%) | 0.89 (0.74 to 1.06) | 0.95 (0.79 to 1.14) | 254/1013 (25.1%) | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.97) | 0.88 (0.77 to 1.00) |

| Year of ART initiation | ||||||

| 2008–2009 | 754/3669 (20.6%) | Reference | Reference | 1505/3669 (41.0%) | Reference | Reference |

| 2010–2011 | 659/3744 (17.6%) | 0.85 (0.77 to 0.94) | 1.04 (0.90 to 1.19) | 1209/3744 (32.3%) | 0.84 (0.78 to 0.91) | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.14) |

| 2012–2013 | 349/2038 (17.1%) | 0.81 (0.71 to 0.92) | 1.22 (1.03 to 1.44) | 466/2038 (22.9%) | 0.71 (0.64 to 0.79) | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.15) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 868/3779 (23.0%) | 1.52 (1.39 to 1.67) | 1.49 (1.34 to 1.65) | 1525/3779 (40.4%) | 1.51 (1.41 to 1.62) | 1.52 (1.41 to 1.64) |

| Female | 894/5672 (15.8%) | Reference | Reference | 1655/5672 (29.2%) | Reference | Reference |

| Age at ART initiation | ||||||

| <30 | 360/1689 (21.3%) | 1.18 (1.02 to 1.36) | 1.04 (0.90 to 1.21) | 673/1689 (39.9%) | 1.34 (1.21 to 1.49) | 1.22 (1.10 to 1.37) |

| 30–34.9 | 343/1957 (17.5%) | 0.95 (0.83 to 1.10) | 0.84 (0.72 to 0.97) | 696/1957 (35.6%) | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.27) | 1.06 (0.95 to 1.18) |

| 35–39.9 | 366/2034 (18.0%) | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.13) | 0.89 (0.77 to 1.03) | 642/2034 (31.6%) | 0.99 (0.89 to 1.10) | 0.93 (0.83 to 1.03) |

| 40–44.9 | 290/1541 (18.8%) | 1.04 (0.89 to 1.20) | 0.99 (0.85 to 1.15) | 482/1541 (31.3%) | 1.00 (0.89 to 1.12) | 0.97 (0.86 to 1.09) |

| ≥45 | 403/2230 (18.1%) | Reference | Reference | 687/2230 (30.8%) | Reference | Reference |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed | 892/5489 (16.3%) | Reference | Reference | 1605/5489 (29.2%) | Reference | Reference |

| Unemployed | 870/3962 (22.0%) | 1.41 (1.28 to 1.54) | 1.23 (1.11 to 1.35) | 1575/3962 (39.8%) | 1.46 (1.36 to 1.57) | 1.32 (1.23 to 1.42) |

| Baseline CD4 count (cells/mm3) | ||||||

| <50 | 675/2374 (28.4%) | 2.79 (2.42 to 3.22) | 1.93 (1.65 to 2.25) | 1048/2374 (44.1%) | 2.11 (1.90 to 2.35) | 1.56 (1.39 to 1.75) |

| 50–99 | 325/1618 (20.1%) | 1.84 (1.56 to 2.17) | 1.40 (1.18 to 1.67) | 573/1618 (35.4%) | 1.56 (1.38 to 1.75) | 1.24 (1.10 to 1.41) |

| 100–199 | 504/3264 (15.4%) | 1.36 (1.17 to 1.58) | 1.22 (1.04 to 1.42) | 1042/3264 (31.9%) | 1.35 (1.21 to 1.50) | 1.22 (1.10 to 1.36) |

| ≥200 | 258/2195 (11.8%) | Reference | Reference | 517/2195 (23.6%) | Reference | Reference |

| BMI at ART initiation (kg/m2) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 534/1754 (30.4%) | 1.87 (1.68 to 2.08) | 1.37 (1.22 to 1.53) | 836/1754 (47.7%) | 1.65 (1.52 to 1.79) | 1.30 (1.19 to 1.41) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 948/5220 (18.2%) | Reference | Reference | 1773/5220 (34.0%) | Reference | Reference |

| 25–29.9 | 194/1637 (11.9%) | 0.63 (0.54 to 0.73) | 0.83 (0.71 to 0.98) | 392/1637 (24.0%) | 0.66 (0.60 to 0.74) | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.96) |

| ≥30 | 86/840 (10.2%) | 0.54 (0.43 to 0.67) | 0.80 (0.64 to 1.01) | 179/840 (21.3%) | 0.58 (0.50 to 0.68) | 0.83 (0.71 to 0.97) |

| WHO stage | ||||||

| I/II | 817/5483 (14.9%) | Reference | Reference | 1564/5483 (28.5%) | Reference | Reference |

| III/IV | 945/3968 (23.8%) | 1.72 (1.57 to 1.89) | 1.13 (1.01 to 1.27) | 1616/3968 (40.7%) | 1.52 (1.42 to 1.63) | 1.10 (1.02 to 1.20) |

| Anaemia at ART initiation | ||||||

| No anaemia | 330/2606 (12.7%) | Reference | Reference | 713/2606 (27.4%) | Reference | Reference |

| Mild anaemia | 367/2326 (15.8%) | 1.27 (1.10 to 1.48) | 1.06 (0.91 to 1.24) | 725/2326 (31.2%) | 1.13 (1.02 to 1.26) | 0.99 (0.89 to 1.10) |

| Moderate anaemia | 810/3751 (21.6%) | 1.84 (1.62 to 2.09) | 1.46 (1.27 to 1.68) | 1382/3751 (36.8%) | 1.43 (1.30 to 1.56) | 1.21 (1.09 to 1.33) |

| Severe anaemia | 255/768 (33.2%) | 3.19 (2.71 to 3.76) | 2.23 (1.85 to 2.67) | 360/768 (46.9%) | 2.10 (1.85 to 2.38) | 1.61 (1.40 to 1.85) |

| Co-infected with tuberculosis at ART initiation | ||||||

| No | 1469/8297 (17.7%) | Reference | Reference | 2662/8297 (32.1%) | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 293/1154 (25.4%) | 1.50 (1.33 to 1.70) | 0.92 (0.80 to 1.06) | 518/1154 (44.9%) | 1.48 (1.35 to 1.63) | 1.00 (0.90 to 1.11) |

| First ART regimen* | ||||||

| TDF-3TC-EFV | 688/3994 (17.2%) | Reference | Reference | 1171/3994 (29.3%) | Reference | Reference |

| d4T-3TC-EFV | 860/4132 (20.8%) | 1.24 (1.12 to 1.37) | 1.03 (0.90 to 1.19) | 1651/4132 (40.0%) | 1.27 (1.18 to 1.37) | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.17) |

| AZT-3TC-EFV | 40/182 (22.0%) | 1.33 (0.97 to 1.83) | 1.26 (0.90 to 1.74) | 62/182 (34.1%) | 1.20 (0.93 to 1.55) | 1.13 (0.86 to 1.46) |

| Other | 174/1143 (15.2%) | 0.87 (0.74 to 1.03) | 0.91 (0.76 to 1.09) | 296/1143 (25.9%) | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.12) | 1.02 (0.89 to 1.17) |

*3TC: lamivudine; AZT: zidovudine; d4T: stavudine; EFV: efavirenz; TDF: tenofovir; Other regimens are: TDF-3TC-NVP (nevirapine), AZT-3TC-NVP, TDF-EMT (emtricitabine)-EFV, TDF-EMT-NVP, and d4T-3TC-NVP.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; BMI, body mass index; LTF, loss to follow-up.

Multiple imputation

In addition to conducting a complete case analysis, we used multiple imputation to account for missing data in our analyses. This led to minor changes in our estimates, though the overall inference remained unchanged. At 1 year after ART initiation, unconfirmed citizens were over 2.5 times more likely to have died or become lost to follow-up as confirmed citizens (aHR 2.72; 95% CI 2.51 to 2.95) with a similar estimate observed at the end of follow-up (aHR 2.70; 95% CI 2.52 to 2.88). A small, though non-significant, effect was observed for foreign nationals compared with confirmed citizens at 1 year (aHR 1.09; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.25) while no association was observed at the end of follow-up (aHR 0.97; 95% CI 0.87 to 1.08) (see online supplementary appendix).

Discussion

The national ID number is a ubiquitous part of everyday life for South African citizens. It is required as proof of identity for a number of situations, including accessing education and employment, applying for a driver's license or passport, voting, registering a mobile phone SIM card, and for accessing household utility services such as water and electricity. Of the unconfirmed citizens at Themba Lethu, some may have known but declined to provide their ID number. Despite its importance, others may lack identification for various reasons: they may never have applied for an ID book due to not having the required documentation or they may have lost their ID book and not applied to have it reissued.

Thus, our findings that unconfirmed South African citizens who did not report a national ID number are at increased risk of attrition from HIV care compared with confirmed South African citizens and foreign nationals raises numerous questions. First, why do these patients not have an ID number recorded? These patients may be truly undocumented South Africans who do not possess an ID number, they may have an ID number but chose to not report it in the clinic, or clinic staff may have failed to have asked for their number. While HIV care is provided free of charge to all who need it in the public sector in South Africa, the cost of other health services is determined via a means test. However, undocumented foreign nationals from non-Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries are excluded from the means test and patients are required to pay for other health-related services in full, regardless of their actual ability to pay. In addition, the policy of free ART regardless of citizenship status in public-sector facilities has not always been uniformly followed, resulting in the need for directives from the Department of Health, issued in 2005 and 2008, to compel clinics to treat all people living with HIV who met eligibility criteria for ART initiation.20 21 As a result of possible fear that they would be denied treatment for not being South African or, for undocumented immigrants deportation, we could speculate that some of the unconfirmed citizens may also be foreign nationals who felt compelled to claim South Africa as their country of citizenship. Thus, some of these patients may actually be foreign nationals misclassified as South Africans.

A second question that our findings raise is why are these patients so much more likely to drop out of care after initiating treatment than any other group of patients? We considered that a survivor bias may exist in this cohort. If patients do not provide their national ID number at their first visit, they may be asked for their ID number at later appointments. Patients who dropped out of care immediately after ART initiation would not have an opportunity to provide their national ID number at a later visit. However, we conducted a sensitivity analysis among only those individuals with at least one follow-up visit at least 7 days after ART initiation and our inferences remained unchanged. It is also possible that migration is a prominent factor in this group and that these patients may have left Johannesburg for another province or, if some are misclassified foreign nationals, they may have returned to their home country. Given that migrants have been shown to be at greater risk for loss from HIV care, it may be reasonable to speculate that some of the attrition observed among unconfirmed South African citizens is related to migration.10 11

Limitations to our analysis include the use of data obtained from a single urban public-sector facility which may limit generalisability, especially to rural areas of South Africa. In addition, as mentioned previously, there may be exposure misclassification as some foreign nationals may be recorded as South African citizens. Likewise, there may also be some outcome misclassification as some of the attrition may be unreported self-transfers to other health facilities. Finally, we also do not have information on migration patterns of this cohort and thus can only speculate as to whether our findings are indicative of migration.

Conclusion

Our results highlight two important factors for the ongoing success of the South African national antiretroviral treatment programme. First, targeted interventions designed to keep patients engaged in care is needed. Further research is warranted to understand more about self-reported South African citizens who do not present a national ID number in order to create interventions that will keep them in care. Second, introduction of a unique identifier for all patients on ART, regardless of citizenship status, is crucial for enabling the linkage of data across health facilities in order to identify self-transfers due to internal migration so that efforts can be focused on tracing patients who have truly dropped out of care and re-engage them in treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the patients, staff, and directors of the Themba Lethu Clinic for their support of this research. In particular, they thank Loraine Malope and Tshepiso Seete for providing invaluable insight into clinic-level procedures relevant to this work.

Footnotes

Contributors: KS designed the study, conducted the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. MPF supervised the study design, data analysis, and drafting of the paper. KC, GM-R, WM, MM, LL and IS provided input into the study design, analysis plan, and drafting of the paper.

Funding: This study was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). This work was funded through the South African Mission of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of Cooperative Agreement 674-A-12-00029 to the Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE2RO), a division of Wits Health Consortium (Pty) Ltd. Additional support to KS was provided by the National Institutes of Health (T32AI102623) and to KC by the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH107256).

Disclaimer: The contents of this publication are the responsibility of the Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, the United States government, or the Themba Lethu Clinic.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the use of de-identified data from the Themba Lethu Clinic was provided by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand and the Institutional Review Board of Boston University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data is owned by the study site and National Department of Health (South Africa) and governed by the Human Research Ethics Committee (University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa). All relevant data is included in the paper and supplementary tables. The full data are available from the Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data and have approval from the owners of the data (information@heroza.org).

References

- 1.The World Bank. Global economic prospects. Washington DC: World Bank, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistics South Africa. Documented immigrants in South Africa, 2012. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budlender D. MiWORC Report No 5. Migration and employment in South Africa: statistical analysis of the migration module in the quarterly labour force survey, third quarter 2012. Johannesburg: Africa Centre for Migration & Society, University of the Witwatersrand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Statistics South Africa. Census 2011: census in brief. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lurie MN, Williams BG. Migration and health in Southern Africa: 100 years and still circulating. Health Psychol Behav Med 2014;2:34–40. 10.1080/21642850.2013.866898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M et al. . Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493–505. 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eaton JW, Johnson LF, Salomon JA et al. . HIV treatment as prevention: systematic comparison of mathematical models of the potential impact of antiretroviral therapy on HIV incidence in South Africa. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001245 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton JW, Menzies NA, Stover J et al. . Health benefits, costs, and cost-effectiveness of earlier eligibility for adult antiretroviral therapy and expanded treatment coverage: a combined analysis of 12 mathematical models. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2:e23–34. 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70172-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy K, Chersich MF, Vearey J et al. . Good treatment outcomes among foreigners receiving antiretroviral therapy in Johannesburg, South Africa. Int J STD AIDS 2009;20:858–62. 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bygrave H, Kranzer K, Hilderbrand K et al. . Trends in loss to follow-up among migrant workers on antiretroviral therapy in a community cohort in Lesotho. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e13198 10.1371/journal.pone.0013198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mutevedzi PC, Lessells RJ, Newell ML. Disengagement from care in a decentralised primary health care antiretroviral treatment programme: cohort study in rural South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2013;18:934–41. 10.1111/tmi.12135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox MP, Maskew M, Macphail AP et al. . Cohort profile: the Themba Lethu clinical cohort, Johannesburg, South Africa. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:430–9. 10.1093/ije/dys029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Department of Health Republic of South Africa. National antiretroviral treatment guidelines 2004. http://www.hst.org.za/sites/default/files/sa_ART_Guidelines1.pdf.

- 14.National Department of Health Republic of South Africa. Clinical guidelines for the management of HIV & AIDS in adults and adolescents 2010. http://www.sahivsoc.org/Files/Clinical_Guidelines_for_the_Management_of_HIV_AIDS_in_Adults_Adolescents_2010.pdf.

- 15.National Department of Health Republic of South Africa. Circular on new criteria for initiating adults on ART at CD4 count of 350 cells/µl and below [letter] 2011.

- 16.National Department of Health Republic of South Africa. The South African antiretroviral treatment guidelines 2013. http://www.sahivsoc.org/Files/2013%20ART%20Treatment%20Guidelines%20Final%2025%20March%202013%20corrected.pdf.

- 17.National Department of Health Republic of South Africa. National consolidated guidelines for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the management of HIV in children, adolescents and adults 2014. http://www.sahivsoc.org/Files/Consolidated%20ART%20guidelines%20_Jan%202015.pdf.

- 18.Fox MP, Brennan A, Maskew M et al. . Using vital registration data to update mortality among patients lost to follow-up from ART programmes: evidence from the Themba Lethu Clinic, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:405–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and mineral nutrition information system. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Department of Health Republic of South Africa. Access to comprehensive HIV & AIDS care including antiretroviral treatment 2005. http://www.sahivsoc.org/Files/2005-Circular-Access-to-ART-for-Pts-without-SA-Identity-Documents.pdf.

- 21.Gauteng Provincial Government Department of Health. Access to the comprehensive HIV and AIDS care including antiretroviral treatment 2008. http://www.sahivsoc.org/Files/2008-Circular-Access-to-ART-for-Pts-without-SA-Identity-Documents.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013908supp_appendix.pdf (608.5KB, pdf)