Abstract

Objectives

Locally led health research in low and middle income countries (LMICs) is critical for overcoming global health challenges. Yet, despite over 25 years of international efforts, health research capacity in LMICs remains insufficient and development attempts continue to be fragmented. The aim of this systematic review is to identify and critically examine the main approaches and trends in health research capacity development and consolidate key thinking to identify a more coherent approach.

Methods

This review includes academic and grey literature published between January 2000 and July 2013. Using a predetermined search strategy, we systematically searched PubMed, hand-searched Google Scholar and checked reference lists. This process yielded 1668 papers. 240 papers were selected based on a priori criteria. A modified version of meta-narrative synthesis was used to analyse the papers.

Results

3 key narratives were identified: the effect of power relations on capacity development; demand for stronger links between research, policy and practice and the importance of a systems approach. Capacity development was delivered through 4 main modalities: vertical research projects, centres of excellence, North–South partnerships and networks; all were controversial, and each had their strengths and weaknesses. A plurality of development strategies was employed to address specific barriers to health research. However, lack of empirical research and monitoring and evaluation meant that their effectiveness was unclear and learning was weak.

Conclusions

There has been steady progress in LMIC health research capacity, but major barriers to research persist and more empirical evidence on development strategies is required. Despite an evolution in development thinking, international actors continue to use outdated development models that are recognised as ineffective. To realise newer development thinking, research capacity outcomes need to be equally valued as research outputs. While some development actors are now adopting this dedicated capacity development approach, they are in the minority.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, TROPICAL MEDICINE, EDUCATION & TRAINING (see Medical Education & Training)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review goes beyond previous attempts that lacked reflexivity, to provide a nuanced, in-depth and enquiring critique of health research capacity development approaches.

This review integrates diverse qualitative literature that largely lacked formal reporting procedures or empirical base, allowing the inclusion of voices that are traditionally excluded in other styles of systematic analyses.

Some academic articles may have been missed because PubMed was the only formal database used, and there was limited inclusion of evaluation and programme-level data due to poor grey literature indexing in Google and Google Scholar.

However, the meta-narrative method aims to develop overarching narratives through saturation of themes, rather than include every eligible article, so inclusion of additional papers would be unlikely to change the findings of the study.

Introduction

Locally led health research is critical for overcoming global health challenges in low and middle income countries (LMICs).1 This research is needed to “propose culturally apt and cost-effective individual and collective interventions, to investigate their implementation, and to explore the obstacles that prevent recommended strategies from being implemented”.2 Such research is now the focus of key capacity development efforts, such as the regional educational centres supported by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR).3

However, these arguments are not new; the importance of LMIC research capacity has been recognised for well over two decades. The 1990 Commission on Health Research for Development stated that strengthening research capacity in LMICs is “one of the most powerful, cost-effective, and sustainable means of advancing health and development”.4 This marked the beginning of a ‘revolution’ in health research5 where there was a surge of investment and concerted effort to conduct health research aimed at solving health problems in LMICs.6

Nevertheless, at the turn of the millennium LMICs accounted for 85% of the world's population, 92% of the global disease burden, but only 10% of global funding for health research was devoted to addressing these persistent health challenges.6 Recognition of this ‘10/90’ gap led to renewed calls for health research capacity development (HRCD) in LMICs and further investment.5

Yet nearly 15 years later, many LMICs still lack sufficient health research capacity to build a local evidence-base with which to inform policy and improve population health. This was recently and profoundly described in The 2013 World Health Report which argued that ‘all nations should be producers and users of research as well as consumers’, noting that this was not yet the case.1

Therefore, despite years of international collaborations and investment, development of LMIC nation's capacity to address their own health problems appears enduringly problematic. Where there has been progress, such gains often do not appear sustainable without continued strong foreign support,7 8 which is itself questionable in light of recent austerity and bilateral aid agency restructuring.1 9 10

Although there is a large and diverse body of literature on HRCD, it remains confusing, controversial and poorly defined, with various contradictory understandings11 and conceptualisations.1 Because capacity development is now something that most research actors are expected to participate in, or at least be knowledgeable on,5 12 this is problematic. To increase the likelihood of future capacity development efforts being effective, there is a need to take stock of past experiences and learn from successes and failures. Such an exercise would not only provide a unifying picture to appraise previous capacity development efforts, but also encourage discussion and reflection that could lead to fresh thinking.

The aim of this systematic review is to identify and critically examine the main approaches, strategies and trends in HRCD and consolidate key thinking in order to identify a more coherent approach. This review should prove useful to all stakeholders interested in learning how to undertake the complex business of capacity development and will be of particular interest to actors working to make locally led and sustainable health research capacity in LMICs a reality.

Methods

Our systematic review followed the six stages of the meta-narrative methodology developed by Greenhalgh et al.13 The meta-narrative method is a “systematic, theory-driven interpretative technique, which [was] developed to help make sense of heterogeneous evidence about complex interventions applied in diverse contexts in a way that informs policy”.14 Since the HRCD literature shares these characteristics, the meta-narrative method was highly suited to the purposes of this study.

Inclusion criteria

This review considers the perspectives of all actors involved in HRCD that have published within academic and grey literature from the year 2000 onwards. We included any papers that broadly discussed HRCD or its more specific components. Papers that mentioned HRCD but did not discuss the issue further were not included. Non-English language publications were excluded due to lack of resources for translation. Papers published before the year 2000 were initially included, but after screening it became clear that paradigm shifts in global health at the turn of the millennium5 6 meant that much of their content was not relevant to current day. Furthermore, many papers published post-2000 effectively summarised historically important issues. Therefore, all papers published pre-2000 were excluded.

Search strategy and study selection

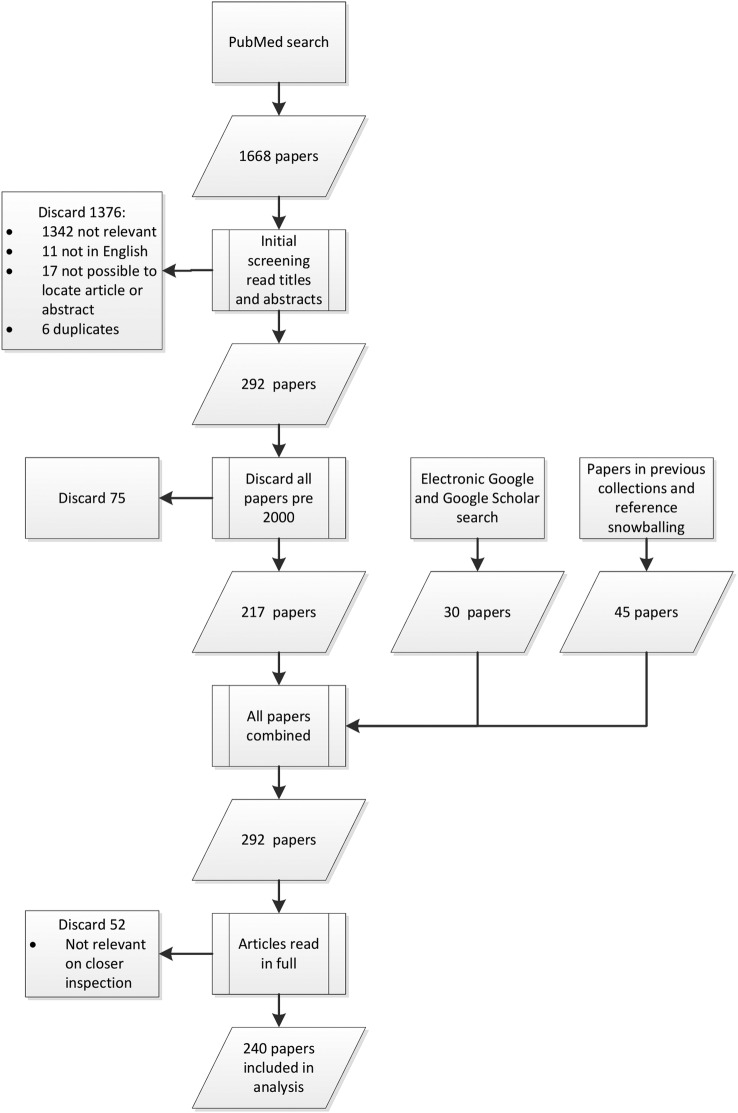

The search and study selection process is presented in figure 1. We searched PubMed using the search terms presented in box 1 for all papers published up to 20 June 2013. This search yielded 1668 potentially relevant papers. The titles and abstracts of these papers were then screened for eligibility, resulting in 1376 papers being excluded based on prescreening, with an additional 75 papers excluded after it was decided that papers published before 1 January 2000 should not be included.

Figure 1.

Search and study selection process.

Box 1. Search terms used in PubMed search.

(((((((((((((((((capacity building[MeSH Terms]) OR (((“developing”[Title/Abstract]) OR “develop”[Title/Abstract]) OR “capacity”[Title/Abstract])))) OR “strengthen”[Title/Abstract]) OR “strengthening”[Title/Abstract])) AND ((((developing country[MeSH Terms]) OR Africa) OR Asia) OR Latin America))) AND (((“trial”[Title]) OR “trials”[Title]) OR “research”[Title])))) NOT clinical trial[Publication Type]) NOT informed consent[MeSH Terms]) NOT waste management[MeSH Terms]) NOT air pollution[MeSH Terms]) NOT agriculture[MeSH Terms]) NOT (“Na6(H2O)8(ZnAsO4)6” [Supplementary Concept] OR “K3Zn4O(AsO4)3” [Supplementary Concept]).

The PubMed search was complemented by a search of Google and Google Scholar using the terms ‘Health AND research AND capacity AND strengthening OR Building OR Development’. All literature added from Google were found in the first 10 pages (n=30). After the first 10 pages, no search results were relevant to the study. Literature collections of the authors and other experts were also hand searched and references snowballed (n=45). A total of 292 papers were read in full and considered for eligibility. On the basis of this screening, the final synthesis involved 240 papers. The full list of papers included in this review can be found in online supplementary file S1.

bmjopen-2016-012332supp1.pdf (361.1KB, pdf)

Relevant papers published between 20 June 2013 and 14 December 2014 were scanned and read to determine if the synthesis findings were still valid postsearch. Although there were some pertinent new articles, their content would not have changed the findings of this synthesis.

Quality assessment

No papers were excluded based on assessment of quality because the majority of papers lacked an empirical or explicit study design, and all stakeholders’ views regardless of their perceived validity were considered important. Furthermore, capacity development discussion is inherently political and most contributions are based on personal opinion informed by theoretical, ethical or experiential standpoint. Accordingly, much of it is biased. Rather than attempt to remove the bias, assumptions and motivations were explicitly studied to undercover authors’ implicit logic, so that readers can make their own informed opinion.

Instead of using quality criteria, similarity of arguments within the literature was used as an indicator of current agreement on a topic or popularity of an idea. This allowed a comprehensive analysis of all the HRCD narratives, while still highlighting and giving emphasis to the most widely accepted opinions.

Data extraction and synthesis

To synthesise the literature, papers need to be framed within a ‘storyline’ that recognises where the contribution came from.13 Greenhalgh et al's13 method explicitly catalogues these storylines as ‘meta-narratives’. Developing meta-narratives provides context to contributions whose underlying assumptions and interests would otherwise be opaque. Although less prescribed than a quantitative systematic review, this approach pragmatically allows a plurality of ideas, recognising that there may be no single correct answer.

To ensure that source content was interpreted alongside its context, even when broken into themes and narratives, a tagging system was used instead of a traditional extraction form. All sources were organised in EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters), and associated citations, metadata and PDF copies of the documents were attached. These data were then imported into Nvivo V.9 qualitative analysis software (QSR International) where the sources were given tags using deductive codes for key characteristics.

Meta-narratives were then identified inductively by reading each paper and coding for meta-narratives where several authors in the literature discussed and presented topics similarly. This is an interpretive approach similar to that used in thematic coding analysis, where reoccurring themes that are conceptually related are grouped into concepts. Once the meta-narratives had been finalised, they were systematically applied to all relevant papers. No prior theory beyond the guidance presented by Greenhalgh et al13 was explicitly used to help identify and categorise the meta-narratives. Instead, iterative rounds of open data-driven inductive coding were used.

Role and position of the authors

This systematic review was undertaken, in part, to inform the design of a larger body of empirical research on HRCD in LMICs. All authors have backgrounds in social science and global health. Initial coding was conducted by Samuel Franzen and then refined based on face-to-face discussions with other authors around the coding framework and preliminary findings. The authors of this paper do not include individuals from LMICs, but this paper was reviewed and commented on by individuals from LMICs who collaborated on and participated in the parallel empirical research, and discussed with other relevant experts at meetings and conferences. These team processes represent a deviation from the meta-narrative method presented by Greenhalgh et al,13 because the authors did not constitute a multidisciplinary team and input from external peers was largely ad hoc, rather than through regular planned inputs. These methodological deviations were required to enable the systematic review to feed into the evolving parallel empirical research.

Results

Definitions and actors

The concept of capacity development can be confusing because there are multiple and conflicting terminologies for development activities and actors. To assist the reader, typologies of key definitions and development actors were produced. Online supplementary file S2 presents these definitions alongside reasons for adopting them, and online supplementary file S3 categorises and provides background to development actors’ activities.

bmjopen-2016-012332supp2.pdf (197.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012332supp3.pdf (28.8KB, pdf)

Characteristics of included papers

Table 1 summarises the main characteristics of the papers included in the review. On the basis of first author characteristics, the greatest number of articles came from LMIC academic and healthcare institutions (31.3%), closely followed by high income countries’ (HIC) academic and healthcare institutions (29.6%). Contributions from funders were very low (0.8%), and industry and civil society were absent, potentially reflecting the sampling from academic databases. Europe was the greatest contributing region (32.9%) followed by sub-Saharan Africa at 23.8% and North America at 13.8%. Contributions from Latin America (2.5%), Middle East (1.7%) and North Africa (0.8%) were low. Although most articles were concerned with capacity development across all LMICs (42.1%), sub-Saharan Africa dominated the regional specific discussions (34.6%). The main basis for viewpoints were opinion, debate or personal perspectives (34.2%); sharing experiences represented 21.7%, and empirical work 20.8%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of papers included in this review

| Category* of development actor (for first author) | Per cent | Location of first author's institution | Per cent | Region of interest | Per cent | Main topic of development interest | Per cent | Main disease of interest | Per cent | Basis for viewpoint | Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMIC academic and healthcare institutions | 31.3 | Europe | 32.9 | All LMIC countries | 42.1 | Multiple broad issues discussed | 24.6 | Not disease specific or address multiple | 72.5 | Opinion, debate, perspective | 34.2 |

| HIC academic and healthcare institutions | 29.6 | Sub Saharan Africa | 23.8 | Sub Saharan Africa | 34.6 | Individual level development | 15.8 | HIV | 6.3 | Experience report | 21.7 |

| Multilaterals | 10.4 | North America | 13.8 | South Asia | 10 | Partnerships networking, consortia | 15.8 | Malaria | 5.8 | Empirical research | 20.8 |

| Consortia and networks, NGOs and public–private partnerships | 8.8 | South Asia | 10 | East Asia | 6.7 | Operational challenges and opportunities | 11.3 | Other | 4.6 | Literature review, summary or synthesis | 7.9 |

| Academic journals | 5.4 | East Asia | 9.2 | All Asia | 2.9 | System approaches and macrolevel development | 9.2 | Mental health and addiction | 2.5 | Proceedings or conference report | 7.5 |

| LMIC governmental | 4.6 | Australia | 2.9 | Latin America | 1.7 | Agenda and priority setting | 6.3 | Maternal child health and paediatrics | 2.5 | Organisation document | 4.6 |

| LMIC funders, research councils and institutes of health | 4.6 | Latin America | 2.5 | Pacific | 0.8 | Institution level development | 5.4 | Tuberculosis | 2.1 | News report | 3.3 |

| Bi-lateral aid agencies | 2.1 | Not specific | 2.1 | Middle East | 0.8 | Monitoring and evaluation | 2.9 | Non-communicable diseases | 2.1 | ||

| HIC research councils and institutes of health | 2.1 | Middle East | 1.7 | Central Asia | 0.4 | Research and development | 2.1 | Dental or oral health | 1.7 | ||

| Private foundations or charity funders | 0.8 | North Africa | 0.8 | Ethics and regulations | 1.7 | ||||||

| Industry | 0 | Pacific | 0.4 | Knowledge cycle | 0.8 | ||||||

| Civil society and media | 0 |

*Some categories have been merged because they could not be separated.

HIC, high income countries; LMIC, low and middle income countries; NGOs, non-governmental organisations.

Meta-narratives in HRCD

Three key narratives ran though the literature: the effect of power relations on capacity development; demand for stronger links between research, policy and practice and the importance of a systems approach to HRCD. Each narrative is described below with reference to the key papers that discussed these narratives in detail.

Effect of power relations on capacity development

The effect of power relations on capacity development was the most common narrative running through the literature (present in 29% of papers). The main concerns of this topic are that research agendas in LMICs are set more by international funders than by LMIC institutions, and research conducted in LMICs is predominantly led by HIC researchers with little involvement of LMIC individuals or institutions. This is argued to erode national sovereignty,15 prevent capacity development16 17 and create research priorities that more closely match funder agendas than countries’ needs18–20 leading to a situation of ‘he who pays the piper calls the tune’.20 21 Examples include ‘spotlight issues’, which receive funding regardless of relative need,22 and ‘parachute’ research where data are collected in LMICs but all other work is conducted in HIC institutions.

‘North–South’ collaborations between HIC and LMIC research institutions are considered to be better mechanisms for developing research capacity,8 but many authors still thought that they comparatively disadvantage the LMIC partner.9 12 15 The perceived situation of ‘treating Africa as a repository of raw materials for expatriate-driven research’9 led to the development of guidelines for research collaboration. To reflect the change in approach, there was a rhetorical shift to using the term ‘partnership’ to describe collaborations that were equitable.17 These partnerships should be built on mutual trust and shared decision-making, national ownership, early planning for translation of research findings and development of national research capacity.17 Importantly, it is now expected that all partnerships should have capacity development at their forefront.12 However, despite discussion for well over a decade, a good proportion of the international community still feels that partnerships are not yet equal,12 23 24 and they cannot be until the power divide is addressed15 because LMICs are unable to negotiate for a fairer deal.15 25 26

In an effort to adjust the power balance, there have been conscious efforts towards recognising local research capacity in LMICs.12 20 This change is again reflected in rhetoric through the evolution of the term ‘capacity development’ which gradually places stronger emphasis on extant capacity; changing from ‘capacity building’ to ‘capacity strengthening’20 to ‘capacity utilisation’,27 ‘unleashing’ and ‘releasing’.20 Many authors now propose that research and capacity development in LMICs should be locally owned and led.17 20 28 29 This is because LMIC researchers have the best understanding of evidence gaps17 and can present research to policymakers with an understanding of the political and cultural context which increases the chance of evidence uptake.30 31 Locally led studies are also thought to be better aligned with national agendas32 and address more applied implementation topics than foreign-led research.17

Most stakeholders now agree that research and capacity development should, at a minimum, include the local research community in the design and conduct of research studies.33 Development actors are also advised to be more sensitive to the power dynamics they create and ensure they strengthen, not weaken, the role of national governments by responding specifically to their priorities20 29 34 and including the ‘recipients’ in any agenda setting.35 However, others argue that this situation will inevitably continue so long as foreign countries are the majority financiers of research in LMICs;36 only through greater national investment and commitment will LMICs have a stronger voice to make relations more equitable.7 9 37 Nevertheless, the vast majority of development efforts reportedly still focus on international collaborative research meaning local investigator-led studies are largely ignored.38 This is evidenced by only three papers in this review being focused on supporting locally led clinical trials, compared to 33 papers aimed at developing international clinical trials.

Demand for stronger links between research, policy and practice

Arguments for stronger links between research, policy and practice were present in 16% of sources. These emerged due to concerns that much research was failing to be translated into policy25 39 and was too narrowly conceived and disease-specific to have impact.40

Accordingly, applied fields now deemed to be highly relevant to decision makers and those that promote sustainable adoption and implementation of evidence-based medicine have been called for.30 41 42 These include health policy and systems research,43 health services research,44 implementation research and operations research.45–47 These arguments formed the backbone of the WHO strategy on ‘research for health’ which “gives priority to research and innovation that has the greatest potential to improve global health security, accelerate health-related development, redress health inequities and help to attain the Millennium Development Goals”.48

Despite these discussions, much research is still regarded as uncoordinated and concentrating on a few high profile diseases49 such as the ‘big 3’: HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. Furthermore, the majority of research is critiqued as largely technology development focused, even though many argue that the impact of this research is low44 and more lives could be saved by improving service delivery of existing interventions.25 43 50

The importance of a systems approach to capacity development

The importance of taking a systems approach to HRCD was discussed in 24% of sources. Conceived in the 1990s and popularised after the Ministerial Summit on Health Research in Mexico in 2004,25 systems approaches to HRCD emerged in response to perceived failings of capacity development targeted at only one level. Particular weaknesses cited included: lack of provision for trained individuals to use their skills6 leading to ‘brain drain’ of LMIC researchers to HICs;51 52 exclusively focusing on high performing individuals53 rather than strengthening local institutions to develop researchers;54 absence of national bodies to coordinate priorities, develop policy and translate evidence into action55 and the fragmentation of capacity development activities.56 57

Proponents of systems approaches argue that for capacity development to be effective and sustainable,8 58 new approaches to addressing all three levels of the national research system are needed; macro, institutional and individual58 (for definitions of these levels, see online supplementary file s2). Macrolevel capacity development should include: priority setting, planning and coordinating research, governance and regulation and knowledge translation and dissemination.48 57 59 Individual development should include a broader range of stakeholders than just research producers (eg, policymakers, administrators, medical personnel and ethics board members) and teach a wider variety of skills and disciplines, particularly ‘soft skills’ such as organisation, management and leadership.55 Institutional development should focus on the ability to generate, retain and use individual capacity through improving curricula, training support, mentorship and research resources.60–62

Although presented as a complex task with long time frames,63 taking a systems approach is said to result in more dynamic capacity development that produces endogenous change, greater local ownership and removal of perennial system barriers20 which helps countries to effectively target their own health needs.19 This is in stark contrast to previous approaches that established parallel structures to deliberately bypass local systems because they were deemed to be chronically ineffective.24 However, despite the accepted importance of research systems development, little is known about how health research systems can be formed,19 there are few successful examples of research system strengthening and little guidance is available.64

A summary of modern HRCD modalities

After attempts at aligning human, material and technical capacities failed in the 1980s, research models that directed funds and technology through HIC institutions became the preferred HRCD mechanism.5 These mechanisms are now the most common approach to HRCD. The justification for requiring LMICs to collaborate with HICs is that knowledge transfer and HIC expertise are required to achieve capacity development.65 66 However, others argue that such development models propagate inequities in research and development.17 36 Discussions on development modalities are therefore contentious. The following sections summarise the justifications, benefits, drawbacks and controversies of the main development modalities.

Vertical research projects

One of the earliest and most persistent research models arising from the HIC fund channelling mechanism was vertical research projects.5 This involves a HIC research collaborator working in a LMIC to conduct applied, normally short-term research projects with narrow objectives.54 The theoretical advantage of a vertical strategy is that it maintains focus on a specific scientific mission.67 This allows the necessary capacity to be developed more rapidly and can quickly produce research outputs5 even where major expansion of R&D is required.35 These approaches now account for the biggest share of health research funding.58 Examples include product development partnerships such as The Global Alliance for TB Drug Development, and many commercial or non-commercial clinical trials.68

HRCD is often included in these programmes, but development of capacity is usually not the primary objective.59 Rather it is designed to develop capacities that will benefit the successful completion of the project60 and result in high-quality research outputs.54 Vertical projects often have strong expatriate leadership and are frequently managed by external institutions,54 which is argued to result in parallel structures that bypass local research institutions.69 Where individual-level development is provided, it is typically short term and project specific.70

Critics of vertical projects argue that local researchers often only have support roles,16 samples may be shipped abroad for analysis23 and there can be little investment in local institutions because they are bypassed.15 69 Therefore when these short-term projects finish, research sites and individuals are rarely left with the skills or resources to run their own studies.41 68 Another criticism is that vertical approaches force the research community to work separately on overlapping issues71 leading to fragmentation of national research systems.55

Proponents of vertical interventions are however mindful that there is a trade-off between the speed and quality of research, and capacity development.72 They argue that in the case of health emergencies, investment should be made in excellent research, not excellent capacity development.

Centres of excellence

A common modality for developing long-term capacity to conduct advanced research in LMICs is ‘centres of excellence’. These have taken various forms, but the approach generally concentrates investment within a few institutions that show potential to excel and become high-quality self-sustaining sites. These models are reportedly useful because they increase the likelihood of high-quality research and renewed investment in an otherwise challenging environment.52 55 73

Early forms of this concept were criticised as being ‘annexed’ research sites, effectively led and managed by expatriate staff.74 Others argue that they create parallel research structures outside of the national system that further depletes the local resource pool by diverting investment and human resources towards these better funded sites.17 24 44 More recent forms of ‘centres of excellence’, such as those championed by the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership, strive for greater Southern leadership and better integration with local research systems.75

North–South partnership

Another common development model is North–South partnerships. They are distinct forms of collaboration between HIC and LMIC researchers because unlike ‘centres of excellence’, they are usually project specific rather than institution building, and they put more emphasis on sustainable research, shared leadership and mutual benefit than vertical research projects. However, depending on the nature of the partnership, these demarcations can become blurred.

Since the millennium, North–South partnerships and have been heavily promoted by organisations such as The Global Forum for Health Research6 and The European and Developing Countries Clinical Trial Partnership (EDCTP).75 Such partnerships are said to be responsible for increasing resource flows to LMICs31 and have been advocated for: increasing scientific productivity,76 training of graduates, staff exchange and knowledge sharing, exposure to cutting edge technology,52 strengthening local education programmes and moderate levels of institutional strengthening.6 77 78 This is argued to result in more sustainable development,54 greater cost-efficiency and a broader research scope than exclusively expatriate-led or locally led research could achieve alone.17 20

Despite their popularity, a greater proportion of the literature is dedicated to discussing problems with North–South partnerships than their benefits. Many authors still feel that despite much guidance for entering into partnerships,12 17 53 79 80 too few benefits are accrued by the Southern partner9 12 23 24 81 because they are forced to collaborate with HIC institutions to meet funding requirements.82 Accordingly, LMIC partners are reported to sometimes receive little financial benefit, go unrecognised in publications and release intellectual property rights.9 12 Proposed amendments to this model have involved adapting partnerships to be driven by LMIC demand,60 led by the Southern partner20 or supporting more South–South partnerships.28 83

Networks and consortia

Networks and consortia development models emerged in the mid-1990s. By the mid-2000s, they were used to tackle whole programmes of research60 and are now very popular with funders.60 Actors adopting network models are highly diverse and can sometimes be hard to separate from partnership models or vertical programmes. However, they all involve linking multiple research departments, groups or institutions.

Networks are considered advantageous because they encourage less-hierarchical leadership and competitive and individualistic attitudes. They are therefore reportedly useful for working cooperatively on shared problems at regional or global levels.84 85 Because networks facilitate information exchange and pooling of resources to achieve a critical mass,86 they are seen as particularly important where groups may be isolated87 or when one group alone would have insufficient capacity to address an issue.88 Networks are also thought to: help focus on common research priorities;60 89 increase knowledge exchange and speed diffusion of innovations57 64 and help forge long-term relationships5 87 and sustainability.37 86 90 91 However, some authors point out that most networks focus on highly thematic research projects60 and only develop capacity of individual research groups, not research systems.87

Specific development strategies

The reviewed literature contained a multitude of development strategies targeted at all levels of the health research system; macro, institutional and individual. These are presented in table 2 and grouped according to the barrier that they address. The research barrier groupings were identified by the authors through thematic coding of the literature content. The popularity of the development strategies are indicated as a percentage of the reviewed sources that proposed them as a solution to a health research barrier.

Table 2.

Summary of capacity development strategies designed to address specific barriers to health research

| Barrier to research | Strategies designed to address barriers to research | Popularity (% of sources) |

|---|---|---|

| Fragmented research systems | Undertake a situational analysis and build on existing assets28

29

57

92 Collaboratively develop research agendas with LMIC stakeholders55 70 75 Create a research coordinating body or scientific councils29 64 93 |

Recently gaining popularity (12) |

| Insufficient research funding | Establish a research finance system using innovative revenue generation52

94

95 Provide long-term funding and flexible grants8 63 96 Advocate for funding through shared causes and engaging with the media68 97 |

Growing popularity (21) |

| Limited use of research evidence | Build capacities of policymakers to demand and scrutinise research25

84

98 Develop evidence repositories and use Research-to-Action-Groups as knowledge brokers to package findings appropriately39 99 Create knowledge translation platforms to support evidence dissemination and dialogue between research producers and users30 39 64 100 |

Consistent popularity (11) |

| Limited governance and regulatory capacity | Work research into a legislative framework64

101

102 Clarify guidelines, map review capacity and streamline procedures74 103 Strengthen regulatory and ethical review capacity42 64 |

Growing popularity (21) |

| Insufficient networking | Develop and share a database of researchers and their expertise31 Use or develop professional networks, especially web-based communities42 71 Organise conferences and working groups on locally important topics2 104 |

Very popular (26) |

| Inefficient admin and research management | Train management and research support staff29

105 Set up a research support office to help with grant management, reporting and contracts, and develop information and finance systems20 28 72 Develop transparent and accountable policies and procedures69 106 |

Unpopular but increasing (8) |

| Inadequate material capacity | Upgrade libraries and journal availability and invest in laboratories28

89

91 Improve information technology, particularly internet6 78 Ensure stable power and water supplies89 |

Widely recognised (20) |

| Insufficient human capacity with research knowledge and skills | Develop LMIC university research training capacity using ‘train the trainer’ programmes, LMIC-HIC ‘sandwich’ courses or visiting research fellowships20

70

92

96

107–109 Make research principles and skills key components of undergraduate and continuing professional medical education37 70 110 Develop a variety of research roles: nurses, data managers, statisticians, laboratory personnel, managers, data collectors9 63 70 107 111–113 Increase distance learning via e-technologies or e-learning resources26 41 70 114 115 Training in major skills gaps: data collection, data management, data analysis and statistics, GCP, laboratory skills, computer literacy and ethics46 51 54 107 116 Training in core capabilities: protocol development, writing for grant applications and publication, grant management and budgeting and policy dialogue29 45 55 63 117 |

Extremely popular (41). Training in core capabilities less popular (15) |

| Insufficient practical research experience | Supplement didactic training with research ‘learning by doing’ opportunities40

47

55 Involve more LMIC institutional staff in research projects54 Exchange visits to advanced research sites to update skills118 Pilot or small grants for early stage researchers to gain experience53 119 |

Fairly accepted (11) |

| Too few research leaders | Develop leadership, project and human resource management skills8

72 Opportunities for junior staff to take responsibility within a supportive environment20 In collaborative projects, local staff must be involved in the entire research process120 |

Gaining popularity (13) |

| Too few mentors and role models | Support mentors with long-term funded positions and recognition73

78 Where mentoring is not available locally, institutional partnerships/exchanges or peer mentorship can be used9 11 55 |

Popular (15) |

| Lack of research culture | Promote academic departmental leaders based on research experience110 Set up a departmental committee to promote research121 Journal clubs and seminars to develop interest in research and critical thinking70 118 |

Not popular (6) |

| Low motivation to conduct research | Protected research time and longer term contracts54

76 Re-entry grants or guaranteed jobs to encourage ‘brain drain’ diaspora to return home107 108 Higher salaries or funded research time to off-set private-practice incentives76 122 |

Popular (18) |

HIC, high income countries; LMIC, low and middle income countries.

Reported success and effectiveness of development efforts

Broadly, authors consider capacity to conduct health research in Africa to have increased considerably since the millennium12 with potential to leverage further gains from current efforts.59 This is best exemplified by increases in the number of clinical trials conducted in LMICs103 123 with reports of enhanced trial capacity,68 particularly laboratories124 and quality standards,38 115 125 and greater LMIC inclusion.105 126 Such institutional strengthening is also thought to have helped reduce brain drain in specific cases.107 Although some countries still lag behind in regulatory and ethical review capacity, several publications indicate that LMICs have made good progress.89 127

The increase in research capacity is thought to have been driven by recognition of the importance of health research over the last 20 years,5 a revised strategic focus30 and the expansion of networks and partnerships for addressing research needs.60 67 91 However, it is not possible to attribute success to these development approaches due to lack of monitoring and evaluation data; in Africa, positive outcomes in the quality and quantity of published research have been recorded,60 107 128 but their connection to development inputs and outputs is not established.129 Operational research and sharing of on-the-ground experiences is thought to be a useful learning resource, but with the exception of a few examples,42 130 little published material on operations is thought to exist.131 This is argued to make it hard to learn from previous efforts and experience60 and determine why and how successes were achieved.28

The paucity of monitoring and evaluation data is a recognised problem,5 58 60 with authors attributing it to long time-lags to achieve objectives,11 outcomes such as organisational culture being difficult to measure,11 lack of commonly agreed and conceptually robust indicators,59 60 102 and most evaluation data not being published.129 To remedy this situation, guidance on planning and implementing monitoring and evaluation for health research has been developed,29 and one research group provides online resources to help record and share operational guidance.41

It was also clear from the literature that significant capacity gaps remain in many LMICs. Following the example of clinical trials, authors point out that early phase studies are still lacking132 and there are too few quality research sites to meet demand.103 Despite increases in some capacities, translation of findings into policy is considered an enduringly difficult outcome60 133 and LMIC leadership and authorship in studies is still thought to be too low.43 Reportedly insufficient political buy-in for strengthening investment in health research has also raised concerns over the sustainability of capacity development achievements.7 8 Some authors argue that longer term projects and planning for sustainability of research staff and services are needed,103 but little literature explores this.63

Discussion

An evolution in HRCD thinking

This literature synthesis has objectively presented the main HRCD modalities and strategies and shows that some development actors continue to operate research models that are contrary to widely accepted views of best practice, for example, expatriate led parallel research units. Nevertheless, the literature reveals that there has been steady progress in health research capacity in LMICs. Development actors have continuously reassessed their approaches and have become much more reflexive of their actions. National stakeholders have taken on a stronger voice and greater ownership and are generally in a more self-sufficient position.

Overall, development actors now agree that there is no panacea or one-size-fits-all model to HRCD. Instead a plurality of solutions exists, the choice of which should be determined by the specific capacities constraints and research goals of LMIC institutions. However, despite progress, major barriers to health research persist, there is little evidence to support decision-making and the sustainability of HRCD achievements is questionable.

HRCD, reality or just rhetoric?

The evolution in HRCD thinking appears promising, but the literature demonstrates that good HRCD practices are not always enacted. While the requirement for short-term projects is recognised,5 the vertical model has been the dominant model for almost 20 years.58 This would indicate that vertical approaches have been used in situations that would be better served by longer term systems strengthening strategies.5 However, there are far fewer programmes dedicated to implementing systems approaches to capacity development. Other examples include focusing on a few high profile diseases, donor-led research agendas, compulsory requirements for collaboration with HICs, setting up parallel structures and fragmentary competitive research. To make the HRCD rhetoric a reality, there is a need to understand why research models that do not enhance or potentially inhibit locally led research remain the modus operandi, even though there is clear agreement that they are bad practice.

The literature findings clearly and frequently show that the persistence of flawed development strategies is driven by approaching capacity development within the context of a dedicated research model. This creates a trade-off between doing good research and doing good capacity development. Projects prioritising good research place research outputs as the primary goal and assume capacity will be developed through limited LMIC involvement in research activities. This means that specific development strategies designed to improve capacity are not used. This ‘implicit’ capacity development is known to be largely ineffective,63 72 yet is it regularly used. As a result, local research systems may fail to develop or deteriorate,22 and development efforts are likely to become multiplicative and fragmented,60 92 despite overlapping interests and generic requirements.71

The other main alternative is ‘explicit’ capacity development. This refers to research projects that place more priority on capacity development and use specific strategies designed to address capacity gaps. There is wide recognition that this is a superior approach and is more likely to improve capacity sustainably.11 63 However, because the research component is usually more valued by the research community, capacity development receives less attention and often focusses on developing project-specific capacities, not addressing systemic deficiencies. Accordingly, the capacity development component often becomes ‘bolted-on’ and ad hoc;11 28 thus making it ‘implicit’ in disguise.

Instead, the review findings suggest that conducting research to improve health in LMICs and developing health research capacity in LMICs must be considered two, sometimes diverging objectives. Recognising this leads to a third way; ‘dedicated’ capacity development. This implies that developing local capacity is as equally valued as the research outputs and should be considered as carefully as the research designs. Owing to the additional resources this requires, previous efforts have been limited to individual capacity development or centres of excellence.91 However, some capacity development actors are now attempting to do this at a more systemic level. Examples include: The Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Disease's (TDR) implementation research programmes,3 ESSENCE on Health Research134 and The Global Health Network.135

Implications for policy and practice

This systematic literature review provides an important synthesis of HRCD that should prove useful for policymakers and practitioners alike. It identifies the strengths, limitations and controversies of the main development approaches and summarises strategies that can be used to overcome specific research system barriers.

Dedicated capacity development appears to offer the best approach for achieving the WHO's vision of all nations becoming producers and users of research.1 However, a key barrier to designing development strategies based on this thinking is the lack of empirical evidence. Without operational and implementation research and quality evaluation data, it is not possible to know the relative effectiveness of different development strategies and difficult to predict if they will be appropriate for a given context. The current experience of sharing data is a good start, but more systematic empirical research is required. This should be performed with the same rigorous attention to methodological design, analysis and reporting standards as any other research endeavour.

Study strengths and limitations

Previous reviews of capacity development have lacked sufficient reflexivity and questioning of assumptions implicit in many strategies.40 This systematic review produced a nuanced and enquiring critique of HRCD approaches in LMICs and has identified dedicated capacity development as a promising strategy for future HRCD efforts. It also integrated diverse qualitative literature that largely lacked formal reporting procedures or empirical base, allowing the inclusion of voices that are traditionally excluded in other styles of systematic analyses.

Some academic articles may have been missed because PubMed was the only formal database used and non-English language articles were excluded. However, the meta-narrative method aims to develop overarching narratives through saturation of themes, rather than include every eligible article, so using additional databases would add little to the study. More problematic was the limited availability and inclusion of programme evaluations and evidence supporting operational learning. While expert opinion and the popularity of development strategies were presented, it was apparent that this is not a reliable indicator of good development practice. Searching Google and Google Scholar, hand searching literature collections and snowballing references did identify the most seminal papers, but some useful organisational documents will have been missed due to poor grey literature indexing. Furthermore, most articles had a general focus or related only to sub-Saharan Africa, meaning that context-specific and research-specific differences could not be examined in detail. The focus of the literature on sub-Saharan Africa is likely due to the high publishing rates of African authors and many papers’ disease specific-focus on high burden diseases of sub-Saharan Africa (HIV and malaria). However, it may also be possible that the English-language search restriction excluded papers from authors publishing about their region in non-English languages. Regardless, the HRCD evidence gap in other developing regions is notable.

It is also important to note that the literature search was carried out on 20 June 2013, so only articles published prior to this date were included in the analysis. A literature scan was carried out on 14 December 2014 which found that the findings were still valid up to this date. It is possible that due to the delay in publication of this article further papers may have been published that could contribute to the findings of this study. While this means that this systematic review may not contain the most up-to-date literature, it is the opinion of the authors’ and peer reviewers’ that the study findings continue to be valid and of important relevance to the global capacity development community. These assertions are supported by the fact that major HRCD agencies such as WHO-TDR and multiagency collaborations such as ESSENCE on Health Research continue to view the issues raised in this paper as problematic. Indeed the 2016 revised version of ESSENCE's Framework for Research Capacity Strengthening136 reiterates the importance of the guiding principles it set out in 2011, while a contemporary WHO-TDR report on Key Enabling Factors in Effective and Sustainable Research Networks137 would suggest that these principles have not yet been achieved.

The limited number of authors working on this review reduced the breadth of perspectives involved during analysis which could have biased interpretation towards the authors’ particular knowledge paradigms and world views. However, this was mitigated to some extent by drawing on perspectives and experiences from concurrent research collaborators and participants, and seeking feedback from relevant experts at meetings and conferences. While some context-specific differences in experiences were inevitably raised, all individuals who were consulted considered the findings of this study to be relevant and consistent with their broad view of HRCD in LMICs. Although it may have been desirable to have a second coder, this would not have necessarily improved the validity of findings through intercoder reliability comparisons because regardless of the number of coders, the emerging coding scheme and findings would always be subjective. Ensuring quality of interpretation relies, rather, on being transparent in offering explanations of meanings rather than presenting definitive causations, and explicitly acknowledging the subjective nature of the analysis and the bias this creates. These principles were adhered to in the research process and the publication.

Conclusions

Despite gains in health research capacity and progress in development thinking, further work is needed to develop sustainable health research systems in LMICs. One promising option is dedicated capacity development in which capacity outcomes are as equally valued as research outputs. However, more empirical research is needed to identify the most effective strategies. If these issues are successfully addressed, health research in all nations could become a reality, rather than just rhetoric.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Sisira Siribaddana and Dr Julius Atashili for their technical advice and intellectual input.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Sisira Siribaddana and Julius Atashili.

Contributors: SRPF, CC and TL conceived and designed the study. SF collected and analysed the data and drafted the manuscript with intellectual input and assistance from CC and TL. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to Professor Trudie Lang (grant reference: OPP1053843), and in part by a Nuffield Department of Medicine Doctoral Prize Studentship to Dr SRPF (http://www.ndm.ox.ac.uk/ndm-prize-studentships).

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Sisira Siribaddana and Julius Atashili

References

- 1.Dye C, Boerma T, Evans D et al. . The World Health Report 2013: research for universal health coverage. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thornicroft G, Cooper S, Bortel TV et al. . Capacity building in global mental health research. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2012;20:13–24. 10.3109/10673229.2012.649117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.TDR. Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases Seven universities selected to host international postgraduate training scheme. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Commission on Health Research for Development. Health research: essential link to equity in development. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davey S. The 10/90 report on health research 2003–2004. Geneva, Switzerland: Global Forum for Health Research, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Global Forum for Health Research. The 10/90 report on health research 2000. Geneva: Global Forum for Health Research, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulland A. Plan to stimulate research in developing countries is put on hold. BMJ 2012;344:e3771 10.1136/bmj.e3771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Annerstedt J, Liyanage S. Challenges when shaping capabilities for research: Swedish support to bilateral research cooperation with Sri Lanka and Vietnam, 1976–2006, and a look ahead. Stockholm: Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laabes EP, Desai R, Zawedde SM et al. . How much longer will Africa have to depend on western nations for support of its capacity-building efforts for biomedical research? Trop Med Int Health 2011;16:258–62. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02709.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies R. Dismantling AusAID: taking a leaf out of the Canadian book? DevPolicyBlog: Development Policy Centre, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bates I, Akoto AY, Ansong D et al. . Evaluating health research capacity building: an evidence-based tool. PLoS Med 2006;3:e299 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marais D, Toohey J, Edwards D et al. . Where there is no lawyer: guidance for fairer contract negotiation in collaborative research partnerships. Geneva and Pietermaritzburg: Council in Health Research for Development, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F et al. . Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: a meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:417–30. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenhalgh T, Wong G, Westhorp G et al. . Protocol—realist and meta-narrative evidence synthesis: evolving standards (RAMESES). BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:115 10.1186/1471-2288-11-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White MT. A right to benefit from international research: a new approach to capacity building in less-developed countries. Account Res 2007;14:73–92. 10.1080/08989620701290341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mony PK, Kurpad A, Vaz M. Capacity building in collaborative research is essential. BMJ 2005;331:843–4. 10.1136/bmj.331.7520.843-b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costello A, Zumla A. Moving to research partnerships in developing countries. BMJ 2000;321:827–9. 10.1136/bmj.321.7264.827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sitthi-Amorn C, Somrongthong R. Strengthening health research capacity in developing countries: a critical element for achieving health equity. BMJ 2000;321:813–17. 10.1136/bmj.321.7264.813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kok MO, Rodrigues A, Silva AP et al. . The emergence and current performance of a health research system: lessons from Guinea Bissau. Health Res Policy Syst 2012;10:5 10.1186/1478-4505-10-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green A, Bennett S, eds. Sound choices: enhancing capacity for evidence-informed health policy. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jentsch B, Pilley C. Research relationships between the South and the North: Cinderella and the ugly sisters? Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1957–67. 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00060-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coloma J, Harris E. From construction workers to architects: developing scientific research capacity in low-income countries. PLoS Biol 2009;7:e1000156 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.González-Block MA, Vargas-Riaño EM, Sonela N et al. . Research capacity for institutional collaboration in implementation research on diseases of poverty. Trop Med Int Health 2011;16:1285–90. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02834.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crane J. Scrambling for Africa? Universities and global health. Lancet 2011;377:1388–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61920-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organisation. Ministerial summit on health research (2004: Mexico City, Mexico). Report from the ministerial summit on health research: identify challenges, inform actions, correct inequities Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lansang M, Dennis R. The need to develop research capacity. Global Forum Update on research for health, Vol 4 London: Pro-Brook Publishing Ltd, 2007:123–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silove D, Rees S, Tam N et al. . Staff management and capacity building under conditions of insecurity: lessons from developing mental health service and research programs in post-conflict Timor-Leste. Australas Psychiatry 2011;19(Suppl 1):S90–4. 10.3109/10398562.2011.583076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DFID. Capacity building in research. DFID, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.ESSENCE on Health Research. Planning monitoring and evaluation; framework for capacity strengthening in health research. ESSENCE Good Practice Document Series Geneva: Copytrend, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aksoy S. Solutions to neglected tropical diseases require vibrant local scientific communities. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010;4:e662 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chandiwana S, Ornbjerg N. Review of North–South and South–South cooperation and conditions necessary to sustain research capability in developing countries. J Health Popul Nutr 2003;21:288–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devasenapathy N, Singh K, Prabhakaran D. Conduct of clinical trials in developing countries: a perspective. Curr Opin Cardiol 2009;24:295–300. 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32832af21b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali R, Finlayson A, Network ICR. Building capacity for clinical research in developing countries: the INDOX cancer research network experience. Global Health Action 2012;5:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Bamako call to action: research for health. Lancet 2008;372:1855 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61789-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lexchin J. One step forward, one step sideways? Expanding research capacity for neglected diseases. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2010;10:20 10.1186/1472-698X-10-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khanna R, Hota P, Lahariya C. Health research strengthening and operational research needs for improving child survival in India. Ind J Pediatr 2010;77:291–9. 10.1007/s12098-010-0037-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mgone CS. Strengthening of the clinical research capacity for malaria: a shared responsibility. Malar J 2010;9(Suppl 3):S5 10.1186/1475-2875-9-S3-S5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shafiq N, Pandhi P, Malhotra S. Investigator-initiated pragmatic trials in developing countries—much needed but much ignored. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;67:141–2. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03291.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kasonde JM, Campbell S. Creating a knowledge translation platform: nine lessons from the Zambia Forum for Health Research. Health Res Policy Syst 2012;10:31 10.1186/1478-4505-10-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vasquez E, Hirsch J, Giang L et al. . Rethinking health research capacity strengthening. Global Public Health, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lang TA, White NJ, Hien TT et al. . Clinical research in resource-limited settings: enhancing research capacity and working together to make trials less complicated. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010;4:e619 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mbuagbaw L, Thabane L, Ongolo-Zogo P et al. . The challenges and opportunities of conducting a clinical trial in a low resource setting: the case of the Cameroon mobile phone SMS (CAMPS) trial, an investigator initiated trial. Trials 2011;12:145 10.1186/1745-6215-12-145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adam T, Ahmad S, Bigdeli M et al. . Trends in health policy and systems research over the past decade: still too little capacity in low-income countries. PLoS One 2011;6:e27263 10.1371/journal.pone.0027263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mgone C, Volmink J, Coles D et al. . Linking research and development to strengthen health systems in Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:1404–6. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02661.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Courtright P, Faal HB. How can we strengthen ophthalmic research in Africa? Can J Ophthalmol 2006;41:424–5. 10.1016/S0008-4182(06)80003-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garcia PJ, Cotrina A, Gotuzzo E et al. . Research training needs in Peruvian national TB/HIV programs. BMC Med Educ 2010;10:63 10.1186/1472-6920-10-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harries AD, Rusen ID, Reid T et al. . The Union and Medecins Sans Frontieres approach to operational research. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:144–54, i. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Health Organisation. The WHO strategy on research for health. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garrett L. The Challenge of Global Health. (Cover story). Foreign Affairs 2007;86:14–38. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whitworth J, Sewankambo NK, Snewin VA. Improving implementation: building research capacity in maternal, neonatal, and child health in Africa. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000299 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goto A, Nguyen TN, Nguyen TM et al. . Building postgraduate capacity in medical and public health research in Vietnam: an in-service training model. Public Health 2005;119:174–83. 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lansang MA, Dennis R. Building capacity in health research in the developing world. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82:764–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nchinda TC. Research capacity strengthening in the South. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:1699–711. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00338-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Magwaza S, Mathambo V, Magongo B et al. . Health research capacity building in South Africa: current knowledge and practices. Durban: Health Systems Trust, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nuyens Y. No development without research. Geneva: Global Forum for Health Research, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pang T, Sadana R, Hanney S et al. . Knowledge for better health: a conceptual framework and foundation for health research systems. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81:815–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organisation. National Health Research Systems. Report of an international workshop, Cha-am, Thailand, 12–15 March 2001 Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bennett S, Adam T, Zarowsky C et al. . From Mexico to Mali: progress in health policy and systems research. Lancet 2008;372:1571–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61658-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ijsselmuiden C, Marais DL, Becerra-Posada F et al. . Africa's neglected area of human resources for health research—the way forward. S Afr Med J 2012;102:228–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones N, Bailey M, Lyytikainen M. Research capacity strengthening in Africa: trends, gaps and opportunities. London: Overseas Development Institute, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kariuki T, Phillips R, Njenga S et al. . Research and capacity building for control of neglected tropical diseases: the need for a different approach. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011;5:e1020 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Minja H, Nsanzabana C, Maure C et al. . Impact of health research capacity strengthening in low- and middle-income countries: the case of WHO/TDR programmes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011;5:e1351 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vogel I. Research capacity strengthening: learning from experience. UK Collaborative on Development Sciences (UKCDS), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chanda-Kapata P, Campbell S, Zarowsky C. Developing a national health research system: participatory approaches to legislative, institutional and networking dimensions in Zambia. Health Res Policy Syst 2012;10:17 10.1186/1478-4505-10-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cooke J. A framework to evaluate research capacity building in health care. BMC Fam Pract 2005;6:44 10.1186/1471-2296-6-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iaccarino M. Mastering science in the South. To develop much-needed research capacity, developing countries cannot rely on the industrialized world, but have to find their own specific solutions. EMBO Rep 2004;5:437–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Higgs ES, Hayden FG, Chotpitayasunondh T et al. . The Southeast Asian Influenza Clinical Research Network: development and challenges for a new multilateral research endeavor. Antiviral Res 2008;78:64 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ogutu BR, Baiden R, Diallo D et al. . Sustainable development of a GCP-compliant clinical trials platform in Africa: the malaria clinical trials alliance perspective. Malar J 2010;9:103 10.1186/1475-2875-9-103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sawyerr A. African universities and the challenge of research capacity development. JHEA/RESA 2004;2:211–40. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gezmu M, DeGruttola V, Dixon D et al. . Strengthening biostatistics resources in sub-Saharan Africa: research collaborations through US partnerships. Stat Med 2011;30:695–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lang T. Advancing global health research through digital technology and sharing data. Science 2011;331:714–17. 10.1126/science.1199349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marjanovic S, Hanlin R, Diepeveen S et al. . Research capacity-building in Africa: networks, institutions and local ownership. J Int Dev 2013;25:936–46. 10.1002/jid.2870 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Whitworth JA, Kokwaro G, Kinyanjui S et al. . Strengthening capacity for health research in Africa. Lancet 2008;372:1590–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61660-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Andronikou S, Mngomezulu V. Paediatric radiology seen from Africa. Part II: recognising research advantages in a developing country. Pediatr Radiol 2011;41:826–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Matee MI, Manyando C, Ndumbe PM et al. . European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP): the path towards a true partnership. BMC Public Health 2009;9:249 10.1186/1471-2458-9-249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dakik HA, Kaidbey H, Sabra R. Research productivity of the medical faculty at the American University of Beirut. Postgrad Med J 2006;82:462–4. 10.1136/pgmj.2005.042713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mayhew SH, Doherty J, Pitayarangsarit S. Developing health systems research capacities through north–south partnership: an evaluation of collaboration with South Africa and Thailand. Health Res Policy Syst 2008;6:8 10.1186/1478-4505-6-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Andruchow JE, Soskolne CL, Racioppi F et al. . Capacity building for epidemiologic research: a case study in the newly independent state of Azerbaijan. Ann Epidemiol 2005;15:228–31. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.de-Graft Aikins A, Arhinful DK, Pitchforth E et al. . Establishing and sustaining research partnerships in Africa: a case study of the UK–Africa Academic Partnership on Chronic Disease. Global Health 2012;8:29 10.1186/1744-8603-8-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gadsby EW. Research capacity strengthening: donor approaches to improving and assessing its impact in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Health Plann Manage 2011;26:89–106. 10.1002/hpm.1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jones AC, Geneau R. Assessing research activity on priority interventions for non-communicable disease prevention in low- and middle-income countries: a bibliometric analysis. Glob Health Action 2012;5:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Muula AS. What drives health research in a developing country? Croat Med J 2007;48:261–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Siriwardhana C, Sumathipala A, Siribaddana S et al. . Reducing the scarcity in mental health research from low and middle income countries: a success story from Sri Lanka. Int Rev Psychiatry 2011;23:77–83. 10.3109/09540261.2010.545991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sadana R, D'Souza C, Hyder AA et al. . Importance of health research in South Asia. BMJ 2004;328:826–30. 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Choi HY, Ko JW. Facilitating large-scale clinical trials in Asia. Urol Oncol 2010;28:691–2. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Strengthening research capacity in Africa. Lancet 2009;374:1 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61213-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bennett S, Agyepong IA, Sheikh K et al. . Building the field of health policy and systems research: an agenda for action. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001081 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee PP, Lau YL. Improving care, education, and research: the Asian primary immunodeficiency network. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2011;1238:33–41. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Excler JL, Pitisuttithum P, Rerks-Ngarm S et al. . WHO-UNAIDS Regional Consultation. Expanding research capacity and accelerating AIDS vaccine development in Asia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2008;39:766–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kilama WL, Chilengi R, Wanga CL. Towards an African-driven malaria vaccine development program: history and activities of the African Malaria Network Trust (AMANET). Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007;77(6 Suppl):282–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Miiro GM, Oukem-Boyer OO, Sarr O et al. . EDCTP regional networks of excellence: initial merits for planned clinical trials in Africa. BMC Public Health 2013;13:258 10.1186/1471-2458-13-258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bringing health research forward. Tanzan J Health Res 2009;11:iii–iv. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kamunyori S, Al-Bader S, Sewankambo N et al. . Science-based health innovation in Uganda: creative strategies for applying research to development. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2010;10(Suppl 1):S5 10.1186/1472-698X-10-S1-S5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Barreto ML. Health research in developing countries. BMJ 2009;339:b4846 10.1136/bmj.b4846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zachariah R, Reid T, Srinath S et al. . Building leadership capacity and future leaders in operational research in low-income countries: why and how? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:1426–35. 10.5588/ijtld.11.0316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lang TA, Kokwaro GO. Malaria drug and vaccine trials in Africa: obstacles and opportunities. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2008;102:7–10. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ntoumi F. Networking and capacity building for health research in Central Africa. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2010;122(Suppl 1):23–6. 10.1007/s00508-010-1331-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sitthi-Amorn C, Pongpanich S, Somrongthong R et al. . The Asian Voice in building equity in health for development—from the Asian Forum for Health Research, Manila, February 2000. Health Policy Plan 2002;17:213–17. 10.1093/heapol/17.2.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.World Health Organisation. Scaling up research and learning for health systems: now is the time. Report of a High Level Task Force, presented and endorsed at the Global Ministerial Forum on Research for Health 2008, Bamako, Mali Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Van Royen K, Lachat C, Holdsworth M et al. . How can the operating environment for nutrition research be improved in sub-saharan Africa? The views of African researchers. PLoS One 2013;8:e66355 10.1371/journal.pone.0066355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kirigia JM, Wambebe C. Status of national health research systems in ten countries of the WHO African Region. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:135 10.1186/1472-6963-6-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.McKee M, Stuckler D, Basu S. Where there is no health research: what can be done to fill the global gaps in health research? PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001209 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mwangoka G, Ogutu B, Msambichaka B et al. . Experience and challenges from clinical trials with malaria vaccines in Africa. Malar J 2013;12:86 10.1186/1475-2875-12-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Thamarangsi T. Addiction research centres and the nurturing of creativity: Center for Alcohol Studies (CAS), Thailand. Addiction 2013;108:1201–6. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03795.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ali R, Finlayson A. Indox Cancer Research Network. Building capacity for clinical research in developing countries: the INDOX Cancer Research Network experience. Glob Health Action 2012;5 doi: 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17288 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.White F. Capacity-building for health research in developing countries: a manager's approach. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2002;12:165–72. 10.1590/S1020-49892002000900004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kellerman R, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Weiner R et al. . Investing in African research training institutions creates sustainable capacity for Africa: the case of the University of the Witwatersrand School of Public Health Masters programme in epidemiology and biostatistics. Health Res Policy Syst 2012;10:11 10.1186/1478-4505-10-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Greenwood B, Bhasin A, Targett G. The Gates Malaria Partnership: a consortium approach to malaria research and capacity development. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:558–63. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02970.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kabiru CW, Izugbara CO, Wambugu SW et al. . Capacity development for health research in Africa: experiences managing the African Doctoral Dissertation Research Fellowship Program. Health Res Policy Syst 2010;8:21 10.1186/1478-4505-8-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Baum BJ, Scott J, Bickel M et al. . 5.3 Global challenges in research and strategic planning. Eur J Dent Educ 2002;6(Suppl 3):179–84. 10.1034/j.1600-0579.6.s3.24.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Halabi-Nassif H, Hatem M. Evidence-based practice and the development of a nursing research culture. Perspect Infirm 2008;5:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Edwards N, Webber J, Mill J et al. . Building capacity for nurse-led research. Int Nurs Rev 2009;56:88–94. 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00683.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]