Abstract

Introduction

Suicide prevention in psychiatric care is arguably complex and incompletely understood as a patient safety issue. A resilient healthcare approach provides perspectives through which to understand this complexity by understanding everyday clinical practice. By including suicidal patients and healthcare professionals as sources of knowledge, a deeper understanding of what constitutes safe clinical practice can be achieved.

Methods

This planned study aims to adopt the perspective of resilient healthcare to provide a deeper understanding of safe clinical practice for suicidal patients in psychiatric inpatient care. It will describe the experienced components and conditions of safe clinical practice and the experienced practice of patient safety. The study will apply a descriptive case study approach consisting of qualitative semistructured interviews and focus groups. The data sources are hospitalised patients in a suicidal crisis and healthcare professionals in clinical practice.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee (2016/34). The results will be disseminated through scientific articles, a PhD dissertation, and national and international conferences. These findings can generate knowledge to be integrated into the practice of safety for suicidal inpatients in Norway and to improve the feasibility of patient safety measures. Theoretical generalisations can be drawn regarding safe clinical practice by taking into account the experiences of patients and healthcare professionals. Thus, this study can inform the conceptual development of safe clinical practice for suicidal patients.

Keywords: Suicidal, suicide prevention, resilient health care, patient experiences, patient safety

Introduction

Although mental illness is the second most important predictor of suicide (behind only past suicide attempts),1 suicides occur rarely in psychiatric inpatient care. From 2004 to 2014 in England, 28% of suicides in the general population were patient suicides; that is, the person had been in contact with mental health services in the 12 months prior to death. Inpatient suicides accounted for 9% of all patient suicides.2 Statistically speaking, inpatient suicides are uncommon, which makes research on suicide highly challenging.3 Nevertheless, suicide is among the most concerning patient safety issues in psychiatric care.

A common understanding of patient safety is the avoidance, prevention and amelioration of adverse outcomes or injuries stemming from the process of healthcare.4 This approach to safety has been characterised as a linear model of risk in which hazards are perceived as phenomena that can be assessed and controlled by implementing different barriers of defences in the system. The linear model of risk represents events in terms of linear causality, where adverse outcomes occur due to combinations of active failures, unsafe acts, and latent conditions and hazards in the system. In the linear approach to safety, safety is achieved when procedures are well implemented in practice without deviations from the standard.5

The background for the linear approach to safety is found in well-understood, well-tested and well-behaved systems and has some limitations when applied to complex systems in which the risk is incompletely understood.6

Healthcare organisations, including psychiatric hospital wards, are examples of complex organisations with multiple stakeholders who interact with each other in a changeable context and make decisions that often involve a high degree of uncertainty.7 Suicide prevention in psychiatric care is arguably complex and incompletely understood as a patient safety issue. First, suicidal behaviour is multifaceted and differs across sexes, age groups, geographic regions and sociopolitical settings, and it is variably associated with different risk factors, suggesting aetiological heterogeneity.3 Second, there is a lack of clear means to assess and treat patients at risk of suicide, which complicates efforts to design safety systems to treat patients in suicidal crises in hospital wards.8–12 There is a need for a deeper understanding of safety for suicidal patients in clinical practice that embraces the complexity and uncertainty of everyday clinical practice.

Resilient healthcare (RHC) is a major discipline that embraces complexity in healthcare. RHC applies non-linear methods to understand and describe how systems work in complex contexts. The main methods used are qualitative case studies. The heart of RHC studies is the collection of knowledge of how everyday clinical work is performed at the sharp end of the system.7 13 RHC is defined by Wears et al14 as follows:

…the ability of the health care system (a clinic, a ward, a hospital, a county) to adjust its functioning prior to, during, or following events (changes, disturbances or opportunities), and thereby sustain required operations under both expected and unexpected conditions (pp. xxvii).

According to the RHC perspective, the purpose of safety management is to ensure that ‘things go right’ and not only to ‘prevent things from going wrong’. Thus, there is a need to learn from successes in clinical practice, in addition to learning from errors. This knowledge is gained by learning about what happens regularly in clinical practice to ensure successful outcomes, including a better understanding of the core business of clinical practice.15

RHC applies a safety II perspective. This perspective acknowledges that healthcare systems are incompletely understood and that their conditions vary. To deal with complexity, healthcare professionals need to adjust their performance to perform the job successfully, and their approach may deviate from standard procedures.15 This approach applies a broader perspective than the traditional linear approach to safety, and it embraces the need to understand why healthcare professionals adapt and what contributes to successes and failures in everyday clinical work. In this sense, knowledge about safe clinical practice for suicidal patients can be collected from the sharp end of the system, which can inform patient safety efforts.16

Aims and research questions

This descriptive study aims to provide a deeper understanding of safe clinical practice for patients hospitalised in a suicidal crisis from an RHC perspective. The specific research questions for the study are as follows:

How does existing literature describe suicidal patients’ experiences regarding safety during psychiatric in-patient care?

How do patients and healthcare professionals describe the components and conditions of ensuring good patient outcomes for suicidal patients in clinical practice?

How do patients and healthcare professionals experience safe clinical practices for suicidal patients?

Methods

Methodological design

The study applies a descriptive case study approach.17 The case is defined as safe clinical practice for patients hospitalised in a suicidal crisis within specialised psychiatric inpatient care.

Study setting

The study setting will be one Norwegian university hospital. Studies of hospitalisation in Norway have found that suicidal behaviour accounts for 70% of all hospitalisations,18 54% of first-time admissions and 62% of rehospitalisations in psychiatric acute wards.19 There are a considerable amount of activities directed to patient safety for suicidal patients in Norwegian hospital wards. Since 2008, national guidelines for preventing suicide in psychiatric hospital wards have been implemented in practice,20 and in 2015, a patient safety campaign for preventing suicide in hospital wards was implemented at a national level.21

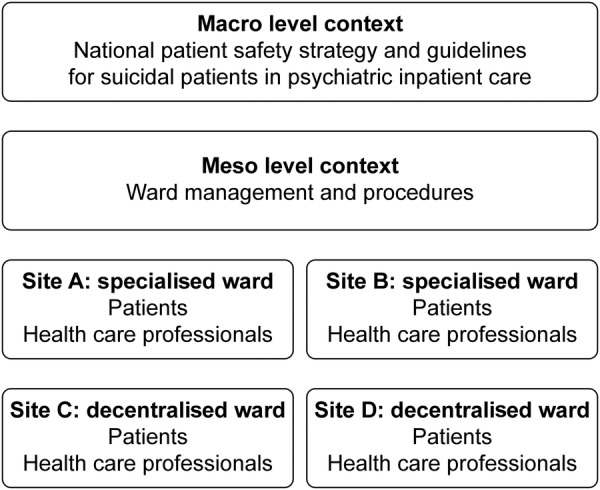

Data collection will take place in four psychiatric hospital wards, two specialised (sites A and B) and two decentralised wards (site C and D). The study sites are selected due to their different structures, staffing levels and tasks. Multiple embedded units of analysis at different levels are included in each ward, consisting of patients and healthcare professionals (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Case study design.

Data collection methods and sources

This case study will conduct qualitative interviews to collect information on the experiences of patients and healthcare professionals. See table 1 for detailed information on the methods, data sources and timing of the data collection.

Table 1.

Data sources, methods, topics and time schedule

| System level | Data collection methods | Data sources | Timing for data collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro level | Systematic review | Qualitative studies | (completed 2017) |

| Semi-structured interviews | Patients Approximately 20 patients from study sites A, B, C and D | September 2017–February 2017 | |

| Focus group interviews 5 focus groups with 6 health care professionals in each group. | Health care professionals Approximately 30 health care professionals (psychologists, physicians, nurses) from closed and open wards at different sites at the hospital. | May-June 2016 | |

| Semi-structured interviews | Health care professionals Approximately 18 health care professionals (psychologists, physicians, nurses) from study sites A, B, C and D. | September 2016 to January 2017 | |

| Meso level | Review of documents Conversations and context mapping | Procedures, patient safety measures Ward managers at site A, B, C and D | January 2016 |

| Macro level | Review of documents | National patient safety programme, national guidelines and laws | January 2016 |

Data on patients’ experiences will be collected through semistructured interviews that are specifically designed to collect in-depth information on their experiences and descriptions of the topics of interest. A systematic review of qualitative studies of suicidal patients has been conducted to inform the development of the interview guide. In addition, an advisory panel consisting of two service user consultants and two key informants on suicide prevention will help develop the interview guides and provide reflections about ethical considerations for the study. Follow-up interviews will be conducted during hospitalisation or after discharge when there is a need for more in-depth information.

Data on healthcare professionals' experiences will be collected through focus group interviews and semistructured individual interviews. The focus groups will provide an opportunity to explore and identify relevant categories and perspectives and for the professionals to correct one another.22 The individual interviews will focus on the professionals' individual sense of making safe and successful practice and will aim to describe in depth the themes that emerge in the focus groups.

Sampling strategy and inclusion criteria

To be included in the study, patients must be hospitalised in specialised psychiatric care for adults, assessed as suicidal during hospitalisation, and able to provide voluntary and informed consent to participate in the study. The therapists (psychologists or physicians) at the study sites will select patients to be recruited to the interviews. As there is no support for the risk categorisation of suicidal patients, any tools or instruments used to clearly define suicidal patients in this study will be of limited value.10 In this study, patients will be considered seriously suicidal if they have presented active suicide ideations or have recently attempted suicide.23

The study will follow a purposeful sampling strategy24 that aims to include patients who have recently been in suicidal crisis and are hospitalised in psychiatric inpatient care. The patients will be enrolled in the study consecutively by ward clinicians. Clinicians' assessment of patients and patients' identification with the topic of interest will determine whether the patient will be included in this study, as shown in box 1. Different experiences of safety are expected to emerge within different levels of hospital protection; thus, this study aims to sample patients in open and locked hospital wards and those admitted both voluntarily and involuntarily. Both men and women and all age groups within adult psychiatry are considered for inclusion (18–65 years).

Box 1. Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria. The interview subject must:

Be hospitalised in an open or closed ward for adults in specialised mental healthcare during the first interview.

Have access to a therapist in specialised mental healthcare during the interviews.

Have been regarded as seriously suicidal by a psychologist or psychiatrist during hospitalisation, but at the time of the interview, patients must be considered sufficiently stable to engage in the interview.

Self-identify as ‘being in a suicidal crisis’.

Voluntarily consent to participate.

Exclusion criteria:

Presenting self-harming behaviour without a desire to die.

Being unable to provide consent, which includes presenting severe psychotic symptoms, severe cognitive deficits or ongoing symptoms of being in a state of crisis with high suicide risk.

This study seeks to describe the safety of hospitalised patients in a suicidal crisis by embracing the complexity and diversity that characterise this phenomenon and the patient group at large. Thus, patients within varying diagnostic groups will be included. The sample description will contain clinicians' diagnoses at discharge, which will be extracted from patients' journals.

The healthcare professionals will be recruited through a purposeful sample strategy.24 The sampling will aim to recruit healthcare professionals with different levels of experience and professional backgrounds. Psychologists, physicians, nurses and social workers at the study sites will be included.

To be included in the semistructured interviews, healthcare professionals must be willing to talk about their experiences with clinical practice and be able to provide voluntary consent to participate in the study. Some participants will participate in the focus groups and the semistructured interviews.

In addition, local procedures and national guidelines and political strategies for suicide prevention in hospital wards will be collected as contextual information.

Researchers' background

SHB is a PhD scholar in risk management and societal safety and a clinical psychologist. SHB has clinical experience with the treatment and assessment of patients at risk of suicide and has a background in safety science. KA is a professor and serves as head of the research group ‘quality and safety in healthcare systems’ at the University of Stavanger. KA has a background in safety science and has conducted multiple studies of patient safety, including studies of patient experiences and RHC studies. KR has a PhD and serves as a mental health nurse and has applied qualitative methods to studies of patient experiences. FAW is a consultant clinical psychologist with extensive work experience in inpatient psychiatry as well as suicide research and national prevention initiatives and guideline development.

The qualitative interviews will be conducted by SHB and KR, who have connections at the university hospital as healthcare professionals and researchers. Their connections to the study site constitute both strengths and dilemmas related to balancing closeness to and distance from participants and studying the sites. These dilemmas will be reflected in all stages of the research process, such as sampling, recruitment, data collection, ethical considerations, analysis and dissemination.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical considerations

Considering the limited amount of evidence on how to provide safe practices for this vulnerable group of patients, access to valid knowledge is of vital importance. Patients can provide insights regarding care and can contribute important information when other sources of evidence in suicide research, particularly feedback regarding sensitive safety-related topics, are limited.25

It is well known that talking about suicide and talking with suicidal patients do not induce harm for patients;26 thus, this study is not considered to induce harm or risk to patients during the study or in the future. Participation in this study empowers patients’ voice and may provide benefits to the patient group at large. However, as patients at risk of suicide represent a vulnerable group, patients will be interviewed while they are in the care of specialised healthcare professionals, enabling those in need of additional support to be referred to the therapist in their hospital ward or in their outpatient unit.

Ward psychologist/physicians will assess patients as sufficiently stable to participate in the interviews, and they will determine the appropriate timing of the interviews.

The hospital will have full responsibility for managing the suicide risk according to ordinary established procedures, and no new procedures or interventions will be implemented as part of this study.

All participants in this study will receive written and oral information about the study and will sign an informed consent form to participate. Patients who are unable to provide informed and voluntary consent will not be included in this study. Information will be collected for research purposes only. Information will be stored unidentified, and all participants will be made unidentifiable in publications.

Dissemination

This study protocol presents preliminary research questions, theories, methods and analytical strategies considered adequate for this purpose. By sharing this information, we aim to address reflexivity in this case study.27

The results of this study will be published in international journals, and presentations will be conducted at national and international conferences. Triangulation of research methods and data sources will be applied to create a viable understanding of safe clinical practices for suicidal patients in psychiatric inpatient care. A literature review will be used as the basis for conducting individual interviews with suicidal patients. Focus group interviews with professionals will be used to describe their experiences with safe clinical practices and as a basis for conducting individual follow-up interviews. Altogether, data from professionals and patients will be integrated in a framework for safe clinical practices for suicidal patients. Details on results from the study are provided in table 2 (planned scientific articles).

Table 2.

Planned scientific articles

| Articles |

Main data source | |

|---|---|---|

| Article 1 | Suicidal patients’ experiences regarding their safety during psychiatric inpatient care: a systematic review of qualitative studies | Qualitative studies |

| Article 2 | Patient experiences of safe clinical practice during a suicidal crisis | Individual in-depth interviews with patients |

| Article 3 | Healthcare professionals experiences with the practice of patient safety for suicidal patients in hospital wards | Focus group study with healthcare professionals |

| Article 4 | Safe clinical practice for patients hospitalised during a suicidal crisis: a resilient healthcare perspective | Focus group study with healthcare professionals Individual in depth interviews with healthcare professionals and patients |

The quality of this study is dependent on its validity. Internal validity is often translated into credibility in qualitative research.28 In this study, credibility will be achieved if the findings of the study make sense for patients and healthcare professionals in clinical practice in psychiatric wards. By including multiple sources of information and methods, this study strives for a nuanced description of the phenomenon of interest, increasing the credibility of the study.

The use of feedback to validate the themes will enhance the credibility and authenticity of this study. Feedback will be collected in the stage of planning and analysis using the advisory panel and presentations in clinical practice and conferences.

The study's external validity is often translated into transferability in qualitative research,28 which indicates the applicability of the findings in other contexts. The use of multiple study sites in the hospital strengthens the external validity in this study. However, the findings of this study are not expected to be valid for the practice of this field overall but rather as descriptions of experiences and meaning within the specific setting of clinical practice for suicidal patients in psychiatric hospital wards in one university hospital in Norway. These findings can generate knowledge to be integrated in the practice of patient safety for suicidal inpatients in Norway and can improve the feasibility of patient safety measures. The findings can further generate knowledge of important topics for safe clinical practice in psychiatry and can inform the future development of structured surveys to measure patients' experiences regarding safety in mental health. Theoretical generalisations can be made regarding what constitutes safe clinical practice while taking into consideration patients' and healthcare professionals' experiences and meanings. Thus, this study can inform the conceptual development of safe clinical practice for suicidal patients.

Acknowledgments

This study is guided by an advisory panel consisting of Dag Lieungh (patient representative), Målfrid Fram Jensen (patient representative), Gudrun Austad (leader of hospital quality improvement group for suicide prevention, Mental Health Nurse) and Kristin A Fredriksen (psychiatrist). The advisory panel read and approved the study protocol. Marie Anbjørnsen (clinical psychologist) will assist with data collection in the focus group interviews. Camilla Hanneli Batalden (clinical psychologist), Sigve Dagsland (clinical psychologist) and Liv Sand (clinical psychologist) will contribute with clinical supervision during the study.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Dag Lieungh, Målfrid Fram Jensen, Gudrun Austad, Kristin A Fredriksen, Marie Anbjørnsen, Camilla Hanneli Batalden, Liv Sand, Sigve Dagsland.

Contributors: SHB had the main idea and design of the study and wrote the main manuscript draft. KA, KR and FAW contributed in the study design and writing of the study protocol.

Funding: This work was supported by The Western Norway Regional Health Authority, grant number 911846.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee (2016/34; Stavanger, Norway).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Only fellow researchers (SHB, KA, KR, FAW) have access to data collected in this study.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Dag Lieungh, Målfrid Fram Jensen, Gudrun Austad, Kristin A Fredriksen, Marie Anbjørnsen, Camilla Hanneli Batalden, Liv Sand, and Sigve Dagsland

References

- 1.Arsenault-Lapierre G, Kim C, Turecki G. Psychiatric diagnoses in 3275 suicides: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2004;4:37 10.1186/1471-244X-4-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appleby L, Kapur N, Shaw J et al. . The National Confidential Inquiry into suicide and homicide by people with mental illness. Making Mental Health Care Safer: Annual Report and 20-Year Review University of Manchester, 2016. http://research.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/cmhs/research/centreforsuicideprevention/nci/reports/2016-report.pdf (accessed Nov 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turecki G, Brent DA. Suicide and suicidal behaviour. Lancet 2016;387:1227–39. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00234-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent CA. Patient safety. London: Elsevier, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollnagel E. Safety-I and safety-II: the past and future of safety management. England: Ashgate, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J, Wears RL. Preface: In the need for resilience in health care. In: Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J, Wears RL, eds. Resilient health care. England: Ashgate, 2013:x–xxvi. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braithwaite J, Clay-Williams R, Nugus P et al. . Health care as a complex adaptive system. In: Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J, Wears RL, eds. Resilient health care. England: Ashgate, 2013:57–73. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wand T. Investigating the evidence for the effectiveness of risk assessment in mental health care. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2012;33:2–7. 10.3109/01612840.2011.616984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Large M, Sharma S, Cannon E et al. . Risk factors for suicide within a year of discharge from psychiatric hospital: a systematic meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2011;45:619–28. 10.3109/00048674.2011.590465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Large M, Ryan C, Nielssen O. The validity and utility of risk assessment for inpatient suicide. Australas Psychiatry 2011;19:507–12. 10.3109/10398562.2011.610505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowers L, Park A. Special observation in the care of psychiatric in-patients: a literature review. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2001;22: 769–86. 10.1080/01612840152713018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D et al. . Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:646–59. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J, Wears RL. Resilient health care. England: Ashgate, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wears R, Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J. Preface. In: Wears R, Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J, eds. Resilient health care volume 2: the resilience of everyday clinical work. England: Ashgate, 2015:xxvii. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollnagel E. Making health care resilient: from safety-I to safety-II. In: Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J, Wear RE, eds. Resilient health care. England: Ashgate, 2013:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wears RL, Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J. Resilient health care, volume 2: the resilience of everyday clinical work. Farnham: Ashgate, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 5th edn Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruud T, Gråwe R, Hatling T.. Akuttpsykiatrisk behandling i Norge.—resultater fra en multisenterstudie. 2006. http://www.sintef.no/globalassets/upload/helse/psykisk-helse/pdf-filer/mapweb.pdf (accessed Jun 2016).

- 19.Mellesdal L, Mehlum L, Wentzel-Larsen T et al. . Suicide risk and acute psychiatric readmissions: a prospective cohort study. Psychiatr Serv 2010;61:25–31. 10.1176/appi.ps.61.1.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Directorate of Health. National Guidelines for Prevention Suicides in Psychiatric Care. 2008. https://helsedirektoratet.no/Lists/Publikasjoner/Attachments/3/Nasjonal-fagligretningslinje-for-forebygging-av-selvmord-i-psykisk-helsevern-IS-1511.pdf (accessed Jun 2016).

- 21.Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services. Prevention of suicide in acute pychiatric inpatient department/Units National Patient Safety Programme: In Safe Hands 2013. http://www.pasientsikkerhetsprogrammet.no/no/I+trygge+hender/In+English (accessed Jun 2016).

- 22.Macnaghten P, Myers G. Focus groups. In: Seale C, Gobom G, Gubrium JF, eds. Qualitative research practice. London: Sage Publications, 2007:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M et al. . Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA's pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164: 1035–43. 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coyne IT. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? J Adv Nurs 1997;26:623–30. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-25-00999.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lakeman R, Fitzgerald M. Ethical suicide research: a survey of researchers. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2009;18:10–17. 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathias CW, Michael Furr R, Sheftall AH et al. . What's the harm in asking about suicidal ideation? Suicide Life Threat Behav 2012;42:341–51. 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.0095.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 2001;358:483–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guba E, Lincoln Y. Effective evaluation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1981. [Google Scholar]