Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to evaluate the proportion of suspected heart failure patients with significant valvular heart disease. Early diagnosis of valve disease is essential as delay can limit treatment and negatively affect prognosis for undiagnosed patients. The prevalence of unsuspected valve disease in the community is uncertain.

Participants

We prospectively evaluated 79 043 patients, between 2001 and 2011, who were referred to a community open access echocardiography service for suspected heart failure. All patients underwent a standard transthoracic echocardiogram according to British Society of Echocardiography guidelines.

Findings to date

Of the total number, 29 682 patients (37.5%) were diagnosed with mild valve disease, 8983 patients (11.3%) had moderate valve disease and 2134 (2.7%) had severe valve disease. Of the total number of patients scanned, the prevalence of aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation, mitral stenosis, mitral regurgitation was 10%, 8.4%, 1%, and 12.5% respectively. 18% had tricuspid regurgitation. 5% had disease involving one or more valves.

Conclusions

Of patients with suspected heart failure in the primary care setting, a significant proportion have important valvular heart disease. These patients are at high risk of future cardiac events and will require onward referral for further evaluation. We recommend that readily available community echocardiography services should be provided for general practitioners as this will result in early detection of valve disease.

Keywords: Community patients

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first largest community study, involving 79 043 patients, looking at the prevalence of valvular heart disease in patients with suspected heart failure, referred by general practitioners.

The study demonstrated that the large proportion of these patients had a significant valvular heart disease that puts them into a high risk of future cardiac events.

The study showed the importance of the open access echo service for general practitioners where immediate diagnosis of heart failure or valve disease could be confirmed.

There is lack of demographic data; however, this is the first study which presents the prevalence of valvular heart disease in such a large number of patients in community.

There is no data on the prevalence of coronary artery disease in this group of patients.

Introduction

Valvular heart disease is an important cause of morbidity and mortality. Early detection and treatment is advocated to improve long-term outcome.1 2 However, a significant proportion of patients with valve disease present late, when the long-term benefits of intervention are less certain. The Euro Heart Survey and other observational studies have demonstrated that around 50% patients having surgery for valve disease were in New York Heart Association III or IV which unnecessarily increases postoperative complications and further mortality.3–6

The study of Nkomo et al identified unsuspected valve disease occuring in 1.8% of healthy adults referred for echocardiography. In contrast, the prevalence of moderate or severe valve disease was 2.5% in healthy adults not being referred for echocardiography.7 The differences in prevalence suggest that there is still a significant number of patients with under diagnosed valve disease.

Among patients admitted to hospital with heart failure the prevalence of valve disease is high (21% as demonstrated by the study of Philbin et al8 9). However, the prevalence of significant valve disease in patients with suspected heart failure in the community is unclear. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of significant valve disease in a large group of patients with suspected heart failure in the community setting.

Methods

Study population

Between January 2001 and 2011 we prospectively acquired the data on patients who were referred to a community open access echocardiography service for suspected heart failure. These data were then retrospectively reviewed. Patients were referred for an echocardiogram by their general practitioner (GP) with heart failure suspected based on clinical symptoms and signs and/or elevated brain natriuretic peptide. The referral base included 25 different regions in the UK.

Echocardiography

All patients underwent a standard transthoracic echocardiogram according to British Society of Echocardiography guidelines from 2005. The assessment of valve regurgitation was performed based on the quantitative parameters including regurgitant volume and effective regurgitant orifice area and supported by semiquantitative methods like vena contracta width and pressure half time.

The severity of valve stenosis was assessed based on the peak gradient and velocity, mean gradient and velocity and valve area. The severity of valve pathology was graded as mild, moderate or severe degree according to British Society of Echocardiography guidelines.

All studies performed and reported by experienced sonographers who were accredited in performing transthoracic examination by British Society of Echocardiography. Twenty per cent of these scans were independently reviewed by a second accredited experienced sonographer or the clinical lead.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 79 043 patients aged >18 years underwent transthoracic echocardiography performed by open access echo service (InHealth Echotech Echocardiography) following a referral from GP with suspected diagnosis of heart failure based on clinical signs and symptoms and/or elevated brain natriuretic peptide.

Echocardiographic results

Of 79 043 patients, 14.1% (11 117 patients) were diagnosed with moderate and severe degree of valve disease with predominantly left-sided valve disease 8.71% (6870 patients). The most common left-sided valve pathology was mitral regurgitation which affected 12.5% (9882 patients) of studied group, the second commonest valve pathology was aortic stenosis 10.05% (7964 patients), followed by aortic regurgitation 8.44% (6673 patients) and the least common being mitral stenosis 1.09% (860 patients). The detailed results of the degree of valve disease are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Prevalence of valvular heart disease in analysed population

| Number of patients | Total percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Aortic stenosis | ||

| Mild | 5420 | 6.85 |

| Moderate | 1620 | 2.03 |

| Severe | 924 | 1.17 |

| Aortic regurgitation | ||

| Mild | 5052 | 6.39 |

| Moderate | 1469 | 1.86 |

| Severe | 152 | 0.19 |

| Mitral stenosis | ||

| Mild | 609 | 0.77 |

| Moderate | 207 | 0.26 |

| Severe | 44 | 0.06 |

| Mitral regurgitation | ||

| Mild | 7410 | 9.37 |

| Moderate | 2117 | 2.68 |

| Severe | 355 | 0.45 |

| Pulmonary stenosis | ||

| Mild | 153 | 0.19 |

| Moderate | 2 | 0.003 |

| Severe | 2 | 0.003 |

| Pulmonary regurgitation | ||

| Mild | 2632 | 3.30 |

| Moderate | 307 | 0.39 |

| Severe | 8 | 0.01 |

| Tricuspid stenosis | ||

| Mild | 12 | 0.01 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | ||

| Mild | 8406 | 10.63 |

| Moderate | 3210 | 4.06 |

| Severe | 718 | 0.91 |

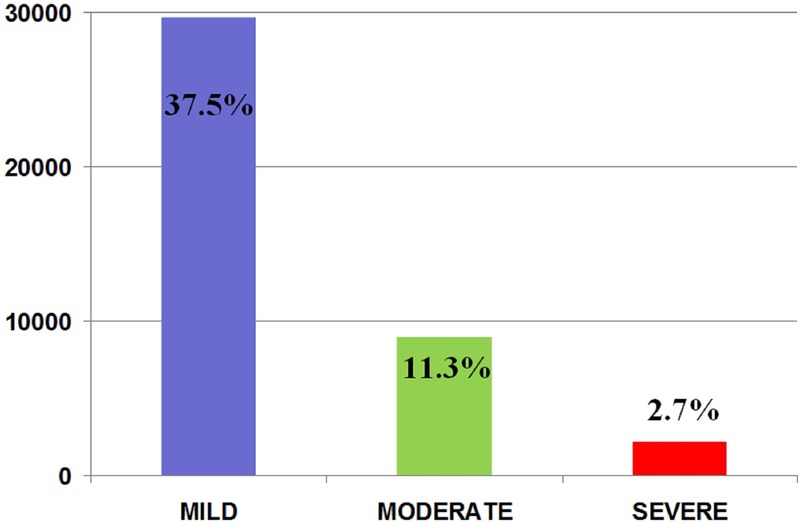

As expected 37.5% (29 694 patients) of patients were diagnosed with mild valve pathology, followed by moderate valve pathology in 11.3% (8932 patients) and severe degree in 2.7% (2203 patients), figure 1.

Figure 1.

The number of patients with diagnosed mild, moderate and severe valve disease.

The interobserver variability in grading the severity of valve disease was 3% with intraobserver variability of 2%. This data was obtained from a snapshot of 200 patients.

Of 79 043 patients, 2371 patients (3%) were diagnosed with mild left ventricular (LV) systolic impairment, 3161 patients (4%) moderate LV impairment and 3972 patients (5%) with severe LV impairment.

Discussion

This is the largest community study (79 043 patients) which has investigated the prevalence of valve disease in patients referred by GPs with a potential diagnosis of heart failure. Of 79 041 patient evaluated, 37.5% had mild valve disease, 11.3% moderate valve disease and 2.7% severe valve disease. This contrasts with the proportion of patients with mild, moderate and severely impaired LV systolic function being 3%, 4% and 5%, respectively. The results have important clinical implications as these patients are at high risk of future cardiac events and a large proportion should be considered for specialist evaluation.

Unsuspected significant valvular heart disease affects at least 2.5% of a healthy US population. The prevalence increases with age, such that 13% of people older than 75 years have at least moderate aortic or mitral valve disease.7 Berry et al10 demonstrated that heart failure complicated 25% of admissions of patients with valve disease therefore early detection is important. Our study has investigated an intermediate set of patients who have not been hospitalised but have been seen in primary care with an echocardiogram request then made after evaluation to look for heart failure.

The implications of this study are large. Increasingly it is recognised that physical signs alone in particular auscultation has a limited sensitivity being insufficient for the diagnosis of valve disease.11 At least a third of patients with severe aortic stenosis are not referred for surgery even when clinically indicated at presentation.12–14 Echocardiography is the gold standard for diagnosis of valve disease, the assessment of the valve disease severity and guiding intervention.14 Given the potential burden of valve disease in the community as demonstrated by our study, much greater provision of echocardiography is required to aid GPs in the diagnosis and management of valve disease.

It has been previously suggested by Arden et al that there needs to be local, national and international educational programmes to encourage GPs and hospital-based non-cardiologists to refer patients with possible valve disease to specialist valve clinics.14 There is no data available on the outcome of these patients referred through open access echo service yet.

We recommend that readily available community echocardiography services should be provided for GPs as this will result in a lower threshold for referral and early detection of valve disease.

Limitations

We recognise that there are limitations of this study due to lack of demographic data including the exact age and gender. The parameters of ventricular function and cavity dimensions were included in the initial reports but this could not be extrapolated from the existing database to allow stratification of valve disease according to these parameters. We also do not have the information with the number of patients with confirmed heart failure on a follow-up. We however wanted to emphasise that this is the first study which presents the prevalence of valvular heart disease in such a large number of 79 043 patients, in community.

The data quoted in interobserver variability for overall valve disease severity between two professionals and intraobserver variability of a single sonographer was in a snapshot of 200 patients. Given the number of scans involved and the number of sonographers involved we have not got variability on the whole sample size.

We also realise that there is no data on the prevalence of coronary artery disease in this group of patients. We showed that 5% of the examined population had severely impaired left ventricular systolic function and 4% moderate impairment. Thanks to the easy access to ‘open access echo service’ a further immediate diagnostic and management plan can be implemented in community patients to further clarify the aetiology of the impairment.

Conclusion

In the community setting, a significant proportion of patients with suspected heart failure have unsuspected important valvular heart disease. These patients are at high risk of future cardiac events and will require onward referral for further evaluation.

Footnotes

Contributors: AM performed the analysis of the data. She wrote the manuscript and revised the important intellectual content. KG contributed to data acquisition and data analysis. RS contributed to data analysis, he revised important intellectual content and was responsible for the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: RS and KG are employed by InHealth/Echotech and receive salaries.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO et al. . 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2438–88. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maganti K, Vera H, Rigolin VH et al. . Valvular heart disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:483–500. 10.4065/mcp.2009.0706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG et al. . A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: the Euro Heart Survey on valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1231–43. 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00201-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lebowitz NE, Bella JN, Roman MJ et al. . Prevalence and correlates of aortic regurgitation in American Indians: the Strong Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:461–7. 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00744-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones EC, Devereux RB, Roman MJ et al. . Prevalence and correlates of mitral regurgitation in a population-based sample (the Strong Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 2001;87:298–304. 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)01362-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindroos M, Kupari M, Heikkilä J et al. . Prevalence of aortic valve abnormalities in the elderly: an echocardiographic study of a random population sample. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;21:1220–5. 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90249-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN et al. . Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet 2006;16:1005–11. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69208-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Philbin EF, DiSalvo TG. Prediction of hospital readmission for heart failure: development of a simple risk score based on administrative data. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:1560–6. 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00059-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowie MR, Wood DA, Coats AJ et al. . Incidence and aetiology of heart failure; a population-based study. Eur Heart J 1999;20:421–8. 10.1053/euhj.1998.1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry C, Lloyd SM, Wang Y et al. . The changing course of aortic valve disease in Scotland: temporal trends in hospitalizations and mortality and prognostic importance of aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1538–47. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arden C, Chambers JB, Sandoe J et al. . Can we improve the detection of heart valve disease? Heart 2014;100:271–3. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant SW, Devbhandari MP, Grayson AD et al. . What is the impact of providing a Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI) service on conventional aortic valve surgical activity, patient risk factors and outcomes in the first two years? Heart 2012;96:1633–7. 10.1136/hrt.2010.203661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindroos M, Kupari M, Valvanne J et al. . Factors associated with calcific aortic valve degeneration in the elderly. Eur Heart J 1994;15:865–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouma BJ, van Den Brink RB, van Der Meulen JH et al. . To operate or not on elderly patients with aortic stenosis: the decision and its consequences. Heart 1999;82:143–8. 10.1136/hrt.82.2.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]