Abstract

Objective

New cholesterol treatment guidelines from American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend statin treatment for more of US population to prevent atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). It is important to assess how new guidelines may affect population-level health. This study assessed the impact of statin use for primary prevention of ASCVD under the new guidelines.

Methods

We used data from 2010 US Multiple Cause Mortality, Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) Linked Mortality File (1988–2006, n=8941) and NHANES 2005–2010 (n=3178) participants 40–75 years of age for the present study.

Results

Among 33.0 million adults meeting new guidelines for primary prevention of ASCVD, 8.8 million were taking statins; 24.2 million, including 7.7 million with diabetes, are eligible for statin treatment. If all those with diabetes used a statin, 2514 (95% CI 592 to 4142) predicted ASCVD deaths would be prevented annually with 482 (0 to 2239) predicted annual additional cases of myopathy based on randomised clinical trials (RCTs), and 11 801 (9251 to 14 916) using population-based study. Among 16.5 million without diabetes, 5425 (1276 to 8935) ASCVD deaths would be prevented annually with 16 406 (4922 to 26 250) predicted annual additional cases of diabetes and between 1030 (0 to 4791) and 24 302 (19 363 to 30 292) additional cases of myopathy based on RCTs and population-based study. Assuming 80% eligible population take statins with 80% medication adherence, among those without diabetes, the corresponding numbers were 3472 (817 to 5718) deaths, 10 500 (3150 to 16 800) diabetes, 660 (0 to 3066) myopathy (RCTs), and 15 554 (12 392 to 19 387) myopathy (population-based). The estimated total annual cost of statins use ranged from US$1.65 to US$6.5 billion if 100% of eligible population take statins.

Conclusions

This population-based modelling study focused on impact of statin use on ASCVD mortality. Under the new guidelines, if all those eligible for primary prevention of ASCVD take statins, up to 12.6% of annual ASCVD deaths might be prevented, though additional cases of diabetes and myopathy likely occur.

Disclaimer:

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study uses national data and nationally representative surveys to estimate the age-sex-race/ethnicity-specific numbers of those who are eligible for statin treatment for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) under the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines.

This study uses the best available data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2010, the National Vital Statistics System, NHANES Linked Mortality File (through 2010) to estimate the age-sex-race/ethnicity-specific ASCVD mortality rates by the statin treatment groups, and the number of ASCVD deaths prevented annually under the 2013 Guidelines.

This study uses the most updated randomised clinical trials or population-based cohort study to calculate the excess incidence of diabetes and myopathy for estimating the additional cases of diabetes and myopathy associated with statins use.

The main limitation of this study is that it focuses on annual ASCVD deaths prevented by statin use, rather than on nonfatal ASCVD events due to a lack of baseline treatment group-specific ASCVD incidence rates at the national level.

Introduction

The 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Guidelines (2013 Guidelines) for the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) in adults recommend statin therapy for primary prevention in (1) individuals with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol ≥190 mg/dL; (2) individuals aged 40–75 years with diabetes; (3) 40–75 years without diabetes but with LDL≥70 mg/dL to ≤189 mg/dL and with ≥7.5% estimated 10-year risk of developing ASCVD.1

Recent studies suggest that under these new guidelines, more than 45 million middle-aged Americans without a history of ASCVD are eligible for statin therapy—13 million more than were eligible under the ATP III Guidelines.2 3 This increase in the statin-eligible population is at least partly the result of new Pooled Cohort Equations that were developed to predict ASCVD risk and determine who might require statin therapy for primary prevention.1 3 Although statins are well tolerated, generally safe, and effective for the prevention of ASCVD,1 4 5 a number of studies—especially population-based cohort studies—have identified side effects associated with statin use, including diabetes, myopathy and liver enzyme abnormalities.4 6–16

To the best of our knowledge, no study has assessed the potential impact of the new guidelines on the annual number of ASCVD deaths prevented and number of adverse side effects that might occur among US adults. For this study, we use national data and representative surveys to estimate the age-sex-race/ethnicity-specific statin-eligible population and prevalence of current statin use among US adults aged 40–75 years. We estimate the annual number of ASCVD deaths prevented, and the predicted additional cases of diabetes and myopathy, if 100% of those who met the criteria for statin therapy for primary prevention of ASCVD were to use statins. We focus on the annual ASCVD deaths prevented by statins use, due to the lack of nationally representative ASCVD incidence rates for the US adults.

Methods

National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES)

NHANES is a continuous series of cross-sectional, stratified, multistage probability surveys of the civilian, non-institutionalised US population. Each survey participant completes a household interview and undergoes a physical examination at a Mobile Examination Center (MEC). Detailed descriptions of NHANES methods are published elsewhere.17 18

We used data from NHANES 2005–2010 to estimate the percentage of participants aged 40–75 years who are eligible for statin therapy for primary prevention of ASCVD, and the prevalence of current statin use. We restricted our analysis to two treatment groups: (1) those aged 40–75 years with diabetes, and (2) those aged 40–75 years without diabetes but with LDL cholesterol ≥70 mg/dL to ≤189 mg/dL and an estimated 10-year risk of developing ASCVD≥7.5%. We did not include participants with LDL≥190 mg/dL due to small sample size in that group. The two treatment groups were labelled as treatment eligibility group 1 and 2, respectively. Diabetes status was determined using either self-report, fasting glucose or glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c). Diagnosed diabetes was defined as participants who answered ‘yes’ when asked whether a physician or other healthcare professional had ever told them that they had diabetes (excluding gestational diabetes) or taking antidiabetic medications. Undiagnosed diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose level ≥126 mg/dL or HbA1c level ≥6.5%.

We used ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equations to estimate the 10-year risk of ASCVD.1 These equations included modifiable risk factors (systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, smoking status, total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol) and non-modifiable risk factors (age, sex and race). In NHANES 2005–2010, blood pressure was measured using a standardised mercury sphygmomanometer after participants rested quietly for 5 min; we calculated the average of up to three blood pressure readings. Participants who reported that they smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and also currently smoked every day or some days were considered current smokers. Total cholesterol was measured using enzymatic reactions, and HDL cholesterol was measured by the direct immunoassay method.19 20 LDL cholesterol was calculated among participants who fasted from 8 to <24 hours and had serum triglycerides ≤400 mg/dL, using the Friedewald formula: LDL cholesterol = total cholesterol − HDL cholesterol − (triglyceride/5).21

Participants were asked to report prescription medications taken in the past 30 days and to bring medication bottles to the MEC where they were recorded. We identified statins using the prescription medication data files and the included Multum Lexicon drug classification scheme.22 Race/ethnicity was categorised as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic and other. For NHANES 2005–2010, from a total of 3909 non-pregnant adults aged 40–75 years with fasting measurements, this study excluded 136 participants with triglycerides >400 mg/dL and deleted 77 participants with missing values on covariates, leaving 3696 adults for prevalence analysis, including 518 adults with ASCVD at baseline and 3178 for primary prevention analysis. National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board approved NHANES. Written consent was obtained for all adults aged ≥18 years.

Multiple cause of death

To estimate the annual number of ASCVD deaths prevented by statin use, we used the 2010 Multiple Cause of Death files from the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) to determine the baseline age-sex-race/ethnicity-specific ASCVD death rates for US population aged 40–75 years.23 The population denominators for ASCVD mortality were from the 2010 US Census. The International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision was used to identify participants for whom ASCVD was listed as the underlying cause of death (codes I20–I25; I63–I69; I70 and I73.9).

Statistical analysis

Statin treatment groups for primary prevention

To estimate the prevalence of statin use by treatment groups, we divided NHANES 2005–2010 participants aged 40–75 years (n=3696) into (1) treatment eligibility group 1 (Diabetes); (2) treatment eligibility group 2 (10-year ASCVD risk ≥7.5%); (3) participants with ASCVD and (4) the remainder. For analysis of primary prevention of ASCVD by statin use, we focused on the first two groups. We calculated the prevalence and 95% CI of current statin use by age group (40 to 49, 50 to 59, 60 to 69 and 70 to 75 years), sex and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic and other).

Age-sex-race/ethnicity-specific ASCVD death rates by treatment groups

The 2010 Multiple Cause of Death data that we use to estimate the baseline ASCVD death rates lacks the information necessary to calculate ASCVD death rates by statin treatment groups at the population level. To estimate the treatment group-specific ASCVD death rates, we used information derived from the 2010 NVSS, the 2010 US Census, NHANES III Linked Mortality Files (1988–2006), and NHANES 2005–2010. Detailed steps of calculation are presented in appendix.

Estimating the population eligible for statin treatment and annual ASCVD prevented

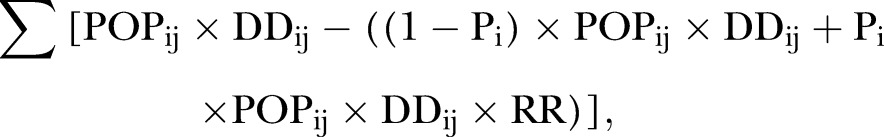

We estimated the age-sex-race/ethnicity-specific population eligible for statin treatment by multiplying the prevalence of non-statin use by the population, denoting it as POPij. We calculated the age-sex-race/ethnicity-specific number of ASCVD deaths prevented annually for treatment group i as follows:

|

where, POPij= age-race/ethnicity-specific eligible population (non-current statin users); DDij= treatment group-specific ASCVD death rates, i=1 to 4 groups, and j=1 to 16 age and race/ethnicity groups (see online supplementary appendix); Pi= proportion of eligible population for statin treatment complied with the statin therapy in treatment group i (assuming 100% statin use in primary analysis); RR= estimated relative risk of 0.83 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.96) for ASCVD mortality among statin users compared with non-statin users.4 We used the 95% CI for the RR of ASCVD mortality to estimate the upper and lower limits of the annual number of ASCVD deaths prevented.

bmjopen-2016-011684supp_appendix.pdf (667.9KB, pdf)

Predicted annual number of additional cases of diabetes and myopathy

We used the results from a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) on statin use and risk of incident diabetes to estimate the annual number of additional cases of diabetes. This meta-analysis reported an excess incidence of diabetes of 1 per 1000 patient-years (95% CI 0.3 to 1.6).8

For myopathy, we used the results from two types of studies to estimate the predicted annual number of additional cases of myopathy: a meta-analysis of RCTs and a population-based cohort study of >2 million patients (QResearch).6 7 The RCT-based estimate of excess incidence of myopathy or rhabdomyolysis was 0.063 (95% CI −0.167 to 0.292) per 1000 patient-years.7 The population-based estimate of myopathy included diagnosed myopathy, rhabdomyolysis, or a raised upper limit of normal creatine kinase concentration ≥4.6 For treatment group 1, the excess incidence of myopathy was 2.176 (95% CI 1.769 to 2.655) and 0.791 (95% CI, 0.545 to 1.100) per 1000 patient-years for men and women, respectively. For treatment group 2, the corresponding rates were 1.864 (95% CI 1.515 to 2.282) and 0.632 (95% CI 0.436 to 0.880), respectively.

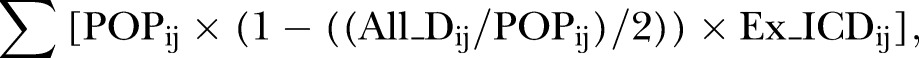

We calculated the annual number of adverse side effects as follows:

|

where, All_Dij= the number of all-cause deaths, assuming that those who died within a year contributed 0.5 person-year, i=1 to 4 groups, and j=1 to 16 age and race/ethnicity groups, and Ex_ICDij= the excess incidence of adverse side effects. The upper and lower limits of the annual number of adverse side effects were obtained by using the 95% CI of excess incidence. Online supplementary table A1 lists the data sources and provides the calculations for the population impact of statin use in primary prevention of ASCVD deaths. Online supplementary table A2 shows the estimated population eligible for statin treatment and ASCVD death rates by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and treatment eligibility groups.

We conducted a sensitivity analyses assuming that 80% of the treatment eligible population would take a statin with a drug adherence rate of 80% (see online supplementary tables A3 and A4). All analyses were conducted using SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and SUDAAN V.11 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA) taking into account the complex sampling design. All tests were 2-sided and considered statistically significant at p<0.05. Data analysis was completed in February 2015.

Results

NHANES 2005–2010 participants included non-Hispanic whites (75.0%), non-Hispanic blacks (9.9%), Hispanics (10.0%) and others (5.1%). The estimated total non-institutionalised population aged 40–75 years was 118.6 million, including 105.2 million without ASCVD. Of those, 10.5% (12.4 million) had diabetes, and 37.7% (95% CI 32.3% to 43.4%) were current statin users. About 17.7% (20.6 million) of those without diabetes would be eligible for primary prevention of ASCVD by statin therapy and 20.5% were already on a statin (table 1). The prevalence of current statin use increased with age, and was higher among non-Hispanic whites and those who had health insurance.

Table 1.

Prevalence of statin use (95% CI) among adults aged 40–75 years, by ACC/AHA cholesterol treatment groups of primary prevention of ASCVD—NHANES 2005–2010

| Diabetes (n=520) |

Estimated ASCVD risk ≥7.5% (n=784) |

Remainder of population aged 40–75 years (n=1874) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Prevalence* | Prevalence of statin use | Prevalence* | Prevalence of statin use | Prevalence* | Prevalence of statin use |

| All | 10.5 (9.3 to 11.8) | 37.7 (32.3 to 43.4) | 17.7 (16.3 to 19.2) | 20.5 (17.3 to 24.0) | 60.4 (58.2 to 62.6) | 12.6 (10.6 to 14.9) |

| Age, years | ||||||

| 40–49 | 6.3 (4.7 to 8.4) | 23.3 (14.5 to 35.3) | 3.1 (2.3 to 4.3) | 0.0 | 84.0 (81.3 to 86.4) | 7.8 (5.4 to 11.0) |

| 50–59 | 11.4 (9.1 to 14.2) | 36.0 (25.0 to 48.6) | 13.3 (11.1 to 16.0) | 11.9 (6.0 to 22.4) | 66.8 (63.1 to 70.4) | 13.8 (10.8 to 17.4) |

| 60–69 | 13.0 (10.9 to 15.5) | 49.1 (37.9 to 60.4) | 35.2 (31.4 to 39.2) | 22.1 (17.2 to 28.0) | 32.1 (28.6 to 35.8) | 25.6 (19.6 to 32.7) |

| 70–75 | 18.0 (14.2 to 22.5) | 42.7 (31.9 to 54.2) | 49.4 (43.7 to 55.1) | 30.5 (22.2 to 40.2) | 10.6 (8.1 to 13.6) | 47.5 (32.1 to 63.4) |

| p Value | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 11.6 (9.6 to 14.0) | 37.2 (29.8 to 45.3) | 24.5 (22.4 to 26.7) | 18.8 (15.0 to 23.4) | 51.0 (48.1 to 53.9) | 14.1 (11.1 to 17.7) |

| Women | 9.5 (8.0 to 11.2) | 38.3 (30.1 to 47.2) | 11.4 (10.0 to 13.0) | 23.6 (17.8 to 30.6) | 69.1 (66.2 to 71.8) | 11.6 (9.6 to 13.9) |

| p Value | 0.155 | 0.858 | <0.001 | 0.235 | <0.001 | 0.124 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white (1) | 8.7 (7.3 to 10.3) | 41.2 (33.2 to 49.8) | 18.4 (16.5 to 20.4) | 22.3 (18.6 to 26.5) | 62.2 (59.2 to 65.1) | 13.4 (11.0 to 16.3) |

| Non-Hispanic black (2) | 17.1 (14.8 to 19.6) | 30.7 (23.6 to 38.8) | 19.1 (16.0 to 22.7) | 13.3 (7.9 to 21.6) | 48.2 (44.0 to 52.3) | 8.4 (5.0 to 13.7) |

| Hispanics (3) | 15.3 (12.9 to 18.0) | 29.3 (22.2 to 37.6) | 13.2 (10.7 to 16.2) | 17.3 (11.0 to 26.1) | 60.7 (56.3 to 65.0) | 5.7 (4.7 to 6.9) |

| p Value (1) vs (2) | <0.001 | 0.055 | 0.708 | 0.020 | <0.001 | 0.041 |

| p Value (1) vs (3) | <0.001 | 0.049 | 0.005 | 0.225 | 0.624 | <0.001 |

| Educational attainment, years | ||||||

| <12 | 14.8 (12.3 to 17.7) | 31.7 (23.8 to 40.8) | 21.2 (18.1 to 24.7) | 17.8 (11.8 to 26.0) | 45.5 (41.7 to 49.4) | 8.8 (5.0 to 15.0) |

| ≥12 | 9.6 (8.3 to 11.1) | 39.7 (33.3 to 46.4) | 16.9 (15.4 to 18.6) | 20.8 (17.1 to 2.9) | 63.6 (61.0 to 66.0) | 13.2 (10.9 to 15.9) |

| p Value | 0.002 | 0.115 | 0.023 | 0.417 | <0.001 | 0.146 |

| Health insurance status | ||||||

| Yes | 10.5 (9.2 to 12.1) | 39.5 (33.4 to 46.1) | 18.0 (16.3 to 19.8) | 22.1 (18.7 to 25.9) | 59.8 (57.2 to 62.3) | 14.2 (12.0 to 16.9) |

| No | 10.2 (7.5 to 13.9) | 26.4 (16.4 to 39.6) | 15.8 (13.3 to 18.6) | 9.2 (5.0 to 16.3) | 64.4 (61.0 to 67.6) | 3.6 (1.8 to 6.9) |

| p Value | 0.736 | 0.033 | 0.101 | <0.001 | 0.132 | <0.001 |

*Weighted prevalence of participants with diabetes, without diabetes but with estimated ASCVD risk ≥7.5%, and remainder of population aged 40–75 years.

ACC/AHA, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

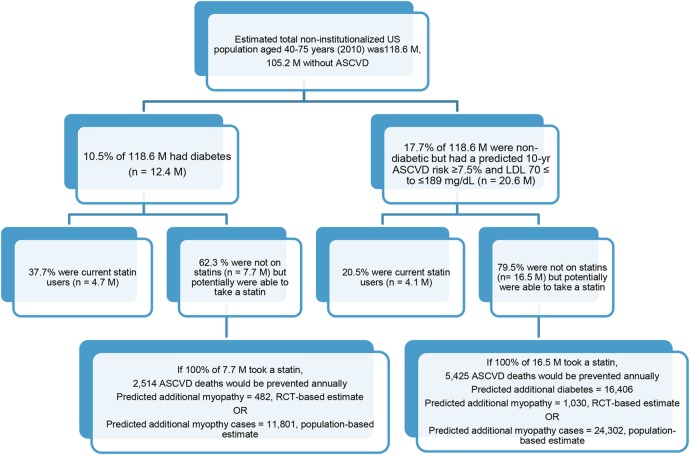

Among 12.4 million adults with diabetes; 7.7 million were not taking statins. If 100% of the 7.7 million were taking statins, 2514 (95% CI 592 to 4142) ASCVD deaths could be prevented annually. However, 482 (95% CI 0 to 2239) additional cases of myopathy could occur using the RCT-based estimate, and 11 801 (95% CI 9251 to 14 916) additional cases of myopathy could occur using the population-based estimate (table 2 and figure 1).

Table 2.

Predicted annual ASCVD deaths prevented and additional cases of myopathy from statin use among participants aged 40–75 years with diabetes—NHANES 2005–2010

| Characteristic | Population with diabetes* (100 000) | Eligible population† (100 000) | Estimated annual ASCVD deaths | ASCVD deaths prevented (95% CI) | RCT-based additional cases of myopathy (95% CI)‡ | Population-based additional cases of myopathy (95% CI)§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 123.5 | 77.0 | 23 380 | 2514 (592 to 4142) | 482 (0 to 2239) | 11 801 (9251 to 14 916) |

| Women | 57.2 | 35.4 | 9150 | 973 (229 to 1602) | 221 (to 1029) | 2787 (1923 to 3878) |

| Age group | ||||||

| 40–49 | 10.3 | 8.6 | 410 | 59 (14 to 98) | 54 (0 to 249) | 675 (466 to 940) |

| 50–59 | 19.0 | 11.5 | 1930 | 213 (50 to 351) | 72 (0 to 335) | 908 (626 to 1263) |

| 60–69 | 16.5 | 8.6 | 3050 | 294 (69 to 485) | 54 (0 to 250) | 677 (467 to 943) |

| 70–75 | 11.3 | 6.7 | 3760 | 406 (95 to 668) | 42 (0 to 193) | 523 (361 to 727) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 42.5 | 26.1 | 6660 | 707 (166 to 1164) | 163 (0 to 759) | 2055 (1418 to 2859) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 6.3 | 3.9 | 1660 | 178 (42 to 293) | 25 (0 to 114) | 309 (213 to 430) |

| Hispanic | 5.3 | 3.3 | 561 | 59 (14 to 98) | 21 (0 to 97) | 264 (182 to 367) |

| Men | 66.3 | 41.6 | 14 230 | 1542 (363 to 2540) | 260 (0 to 1210) | 9014 (7328 to 11 038) |

| Age group | ||||||

| 40–49 | 17.2 | 12.6 | 1600 | 209 (49 to 343) | 79 (0 to 367) | 2734 (2222 to 3348) |

| 50–59 | 258 | 17.2 | 5130 | 616 (145 to 1014) | 107 (0 to 499) | 3718 (3022 to 4552) |

| 60–69 | 16.6 | 8.2 | 4250 | 392 (92 to 646) | 51 (0 to 238) | 1775 (1443 to 2173) |

| 70–75 | 6.7 | 3.7 | 3240 | 325 (77 to 536) | 23 (0 to 105) | 781 (635 to 956) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 49.7 | 31.0 | 10 950 | 1184 (278 to 1949) | 193 (0 to 899) | 6701 (5447 to 8205) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 6.4 | 4.1 | 1950 | 214 (50 to 352) | 25 (0 to 118) | 882 (717 to 1080) |

| Hispanic | 6.6 | 4.3 | 880 | 96 (23 to 158) | 27 (0 to 124) | 926 (753 to 1134) |

*Population = number of adults aged 40–75 years with diabetes in 100 000.

†Eligible population = number of adults aged 40–75 years with diabetes multiplied by (1-prevalence of current statin use).

‡The estimated excess number of myopathy cases was based on an meta-analysis of RCTs estimate of the excessive incidence of myopathy, 0.0628 per 1000 patient-years.7

§The estimated excess number of myopathy cases was based on a population-based cohort study with over 2 million patients.6 The excess incidence of myopathy per 1000 patient-years was 2.176 (95% CI 1.769 to 2.655) for men and 0.791 (95% CI 0.545 to 1.100) for women.

ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; RCT, randomised clinical trial.

Figure 1.

Predicted annual ASCVD deaths prevented and additional adverse events from statin use among participants 40–75 years—NHANES 2005–2010. ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; RCT, randomised clinical trial.

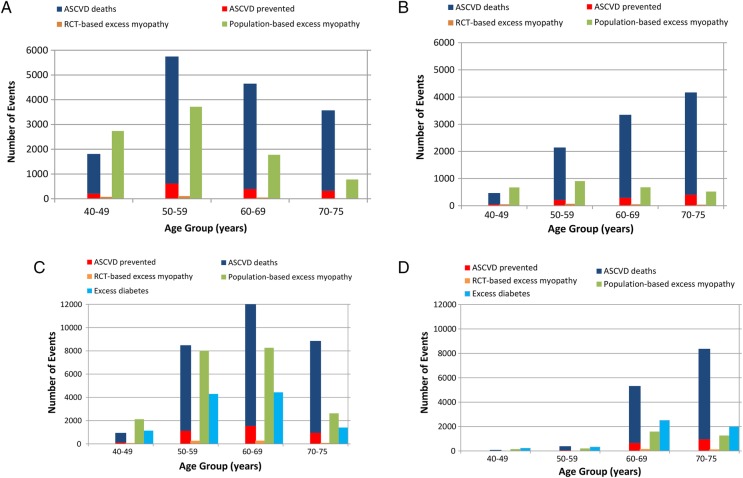

The annual number of ASCVD deaths prevented increased with age, and there are about 1.5 times more deaths among men than among women (figure 2A, B). On average, about five additional cases of myopathy are predicted for every ASCVD death prevented using the population-based estimate.

Figure 2.

Predicted annual ASCVD deaths prevented and additional cases of diabetes and myopathy from statin use among US men (A) and women (B) Aged 40–75 years with diabetes, and among, men (C) and women (D) without diabetes, but with 10-year risk ≥7.5% for ASCVD. ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; RCT, randomised clinical trial.

Among 20.6 million adults in treatment group 2, 4.1 million were taking statins and 16.5 million were eligible for statin treatment. The predicted annual number of ASCVD deaths prevented is 5425 (95% CI 1276 to 8935). The predicted additional cases of diabetes are 16 406 (95% CI 4922 to 26 250). Using the RCT-based estimate, the predicted number of additional myopathy cases is 1030 (95% CI 0 to 4791), and 24 302 (95% CI 19 363 to 30 292) using the population-based estimate (table 3 and figure 1). The annual number of ASCVD deaths prevented increased with age and were ∼2.3 times greater among men than among women (figure 2C, D).

Table 3.

Predicted annual ASCVD deaths prevented and additional cases of diabetes and myopathy from statin use among participants 40–75 years, without diabetes and with ≥7.5% 10-year ASCVD risk—NHANES 2005–2010

| Characteristic | Population* (100 000) | Eligible population† (100 000) | Estimated annual ASCVD deaths | ASCVD deaths prevented (95% CI) | Excess number diabetes (95% CI) | RCT-based additional cases of myopathy (95% CI)‡ | Population-based additional cases of myopathy (95% CI)§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 206.2 | 164.8 | 39 880 | 5425 (1276 to 8935) | 16 406 (4922 to 26 250) | 1030 (0 to 4791) | 24 302 (19 363 to 30 292) |

| Women | 66.6 | 51.1 | 12 500 | 1661 (391 to 2736) | 5093 (1528 to 8149) | 320 (0 to 1487) | 3219 (2221 to 4479) |

| Age group | |||||||

| 40–49 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 73 | 12 (3 to 20) | 232 (70 to 371) | 15 (0 to 68) | 146 (101 to 204) |

| 50–59 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 340 | 47 (11 to 78) | 331 (99 to 529) | 21 (0 to 97) | 209 (144 to 291) |

| 60–69 | 31.9 | 25.3 | 4670 | 653 (154 to 1075) | 2514 (754 to 4022) | 158 (0 to 734) | 1589 (1096 to 2211) |

| 70–75 | 28.2 | 20.2 | 7420 | 949 (223 to 1563) | 1994 (598 to 3191) | 125 (0 to 582) | 1260 (870 to 1754) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 51.1 | 39.1 | 9270 | 1230 (289 to 2025) | 3897 (1169 to 6235) | 245 (0 to 1138) | 2463 (1700 to 3427) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 6.7 | 5.2 | 2070 | 277 (65 to 455) | 516 (155 to 825) | 32 (0 to 151) | 326 (225 to 453) |

| Hispanic | 5.4 | 4.2 | 777 | 103 (24 to 170) | 416 (125 to 666) | 26 (0 to 122) | 263 (182 to 366) |

| Men | 139.6 | 113.7 | 27 380 | 3764 (886 to 6199) | 11 313 (3394 to 18 101) | 711 (0 to 3304) | 21 084 (17 142 to 25 813) |

| Age group | |||||||

| 40–49 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 807 | 137 (32 to 226) | 1138 (342 to 1821) | 72 (0 to 332) | 2122 (1725 to 2597) |

| 50–59 | 48.5 | 43.1 | 7350 | 1132 (266 to 1865) | 4296 (1289 to 6873) | 270 (0 to 1254) | 8006 (6509 to 9802) |

| 60–69 | 58.1 | 44.8 | 11 320 | 1544 (363 to 2543) | 4435 (1331 to 7096) | 279 (0 to 1295) | 8265 (6720 to 10 119) |

| 70–75 | 21.5 | 14.4 | 7900 | 951 (224 to 1566) | 1409 (423 to 2254) | 88 (0 to 411) | 2625 (2134 to 3214) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 107.3 | 87.0 | 21 230 | 2914 (686 to 4799) | 8657 (2597 to 13 850) | 544 (0 to 2528) | 16 132 (13 116 to 19 751) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 12.8 | 10.5 | 3640 | 505 (119 to 832) | 1044 (313 to 1671) | 66 (0 to 305) | 1947 (1583 to 2383) |

| Hispanic | 12.2 | 10.1 | 1670 | 230 (54 to 379) | 1010 (303 to 1616) | 63 (0 to 295) | 1883 (1531 to 2305) |

*Population = number of adults aged 40–75 years without ASCVD but with a ≥7.5% 10-year ASCVD risk in 100 000.

†Eligible population = number of adults aged 40–75 years without ASCVD but with ≥7.5% 10-year ASCVD risk multiplied by (1-prevalence of statin use).

‡The estimated excess number of myopathy cases was based on a meta-analysis of RCTs estimate of the excessive incidence of myopathy, 0.0628 per 1000 patient-years.7

§The estimated excess number of myopathy cases was based on a population-based cohort study with over 2 million patients.6 The excess incidence of myopathy per 1000 patient-years was 1.864 (95% CI 1.515 to 2.282) for men and 0.632 (95% CI 0.436 to 0.880) for women.

ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; RCT, randomised clinical trial.

Assuming 80% of the eligible population were to take statins with a drug adherence rate of 80%, 1609 (95% CI 379 to 2651) ASCVD deaths would be prevented annually and the predicted annual additional cases of myopathy would be 7553 (95% CI 5921 to 9546) using population-based estimate, and 308 (95% CI 0 to 1433) using RCT-based estimate for treatment group 1 (see online supplementary table A3). For treatment group 2, the predicted annual number of ASCVD deaths prevented would be 3472 (95% CI 817 to 5718), the predicted annual additional cases of diabetes would be 10 500 (95% CI 3150 to 16 800), the predicted annual additional cases of myopathy would be 15 554 (95% CI 12 392 to 19 387) using population-based estimate and 660 (95% CI 0 to 3066) using RCT-based estimate (see online supplementary table A4).

Discussion

In the USA, nearly 800 000 people die each year from cardiovascular disease (CVD), making it the leading cause of death.24 High blood cholesterol levels are associated with an increased risk of CVD events and deaths, and the use of statins is associated with a significant reduction in that risk.25 A substantial body of evidence has demonstrated a reduction in incidence and mortality from ASCVD with a good margin of safety from statin therapy,4 5 25 however, other studies, especially population-based cohort studies, have identified several adverse side effects associated with statins use.4–10 13 Under the 2013 Guidelines, many US adults are potentially eligible for statin treatment for primary prevention of ASCVD.2 3 In addition, compared with the ATP III guidelines and current guidelines from other authorities, such as European Society of Cardiology and the European Atherosclerosis Society,26 27 the ACC/AHA 2013 Guidelines have eliminated LDL-C treatment target values and focused on the specific statin regimens that produce a percentage reduction in LDL-C. One study has summarised the similarities and differences between the ACC/AHA Guidelines and other current guidelines.28 Using national data and nationally representative sample surveys, we estimated that among 24.2 million American adults aged 40–75 years eligible for, but not taking a statin, primary prevention, 7939 ASCVD deaths could be prevented if 100% of those eligible were on statin treatment, which represent ∼13% of the total number of annual ASCVD deaths among the two primary treatment groups. The number of ASCVD deaths prevented increases with age, and >70% of ASCVD deaths prevented would occur among those aged 60–75 years. It is important to point out that our study focused on ASCVD deaths prevented by statin use, rather than non-fatal ASCVD events due to lack of nationally representative ASCVD incidence rates by the treatment groups we examined. Although the national vital statistics system is the best data available for tracking mortality, recommended statin use under the 2013 Guidelines would prevent a larger number of non-fatal ASCVD events annually, given there were about 915 000 CHD events versus about 380 000 CHD deaths and 610 000 stroke events vs 130 000 stroke deaths in 2010 in the USA.29 A recent meta-analysis of RCTs on statins and primary prevention of CVD indicated that 18 out of every 1000 people treated with a statin for five years would avoid a major CVD event.4 If this absolute risk reduction applied across all age-sex-race/ethnicity-strata, ∼87 000 ASCVD events would be prevented annually, if all 24.2 million of the eligible population under the 2013 Guidelines were to take a statin. It is apparent that the ASCVD deaths rates were considerably lower than the ASCVD events rates, statin use would prevent a larger number of non-fatal ASCVD events annually, and our findings should not be misinterpreted in terms of benefits and side effects associated with statin use. However, despite of the limitations, our results provide a comprehensive assessment of the overall impact of statins use in terms of annual ASCVD deaths prevented and additional annual cases of adverse events that could occur from population perspective. The findings of our study might also provide useful information for clinicians and potentially patients to discuss the benefit-risk profile of statin use at the individual level, and help them to make the informed decision.

The 2013 Guidelines emphasise the importance of lifestyle modification (ie, regular exercise, having heart healthy diet, avoiding tobacco products and maintaining a healthy weight) for ASCVD risk reduction and improving overall health. Lifestyle modification is recommended prior to and in concert with statin therapy.25 30 Previous studies have suggested that >75% of CVD and stroke incidence might be attributable to modifiable risk factors, making lifestyle modifications the foundation of primary and secondary prevention of ASCVD.30–32 Implementation of individual and population-level strategies to reduce modifiable CVD lifestyle risk factors could play an important role in reducing incidence and mortality of CVD.33 Such lifestyle modifications would improve individual cardiovascular outcomes and overall health, regardless of risk factor profiles.

Among the 16.5 million individuals with a predicted 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥7.5% (treatment eligibility group 2), statin therapy would result in ∼16 406 additional cases of diabetes annually, or three additional cases of diabetes per ASCVD death prevented. Several meta-analyses of RCTs have documented an increased risk of diabetes associated with statin use, with estimated RRs ranging from 1.09 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.16) to 1.18 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.39), and excess incident diabetes ranging from about one to three cases per 1000 patient-years.4 5 8 11 12 34 For primary prevention of CVD with statins, the excess incidence of diabetes was 1.5 to 2.0 per 1000 patient-years from the meta-analyses of RCTs.4 5 11 However, because the estimated excess incidence of diabetes was dominated by one trial that used a higher statin dose, we used a conservative estimate of 1 per 1000 patient-years in our analysis.4 5 8

Diabetes is a major risk factor for CVD. Studies suggest that adults with diabetes are 2–4 times more likely to experience CVD or stroke, and that >65% of them will die from CVD or stroke (http://www.ndep.nih.gov/media/CVD_FactSheet.pdf). However, another study argued that most of the individuals taking statins who developed diabetes would become diabetic anyway, because of major risk factors they might have, suggesting that the date of diabetes diagnosis might be simply accelerated by taking statins.35 A recent modelling-based cost-effectiveness study of statin treatment under the 2013 Guidelines concluded that using a threshold of ≥7.5% 10-year ASCVD risk has an acceptable cost-effectiveness profile with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of US$37 000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, and a more lenient ASCVD thresholds would be optimal using cost-effectiveness thresholds of US$100 000/QALY (≥4.0% risk threshold) or US$150 000/QALY (≥3.0% risk threshold).36 Using the annual individual cost of statins use cited in this study, the estimated total annual cost of statins use ranged from US$1.65 billion for the generic-based statins use to US$6.5 billion for the base-case statins use if 100% of eligible population for statin therapy take statins. Further studies are warranted, which take into account the additional cases of diabetes and other adverse events, to examine the long-term benefit, harm and cost-effectiveness of statin use in the primary prevention of ASCVD.

Other adverse side effects associated with statin use might occur.4–7 9–11 13 37 Increased risk of myopathy and elevation of liver enzymes are two commonly discussed adverse effects. A recent meta-analysis of observational studies found evidence of an increased risk for myopathy, and liver enzyme elevation associated with statin use in addition to type 2 diabetes.9 We focused on increased risk for diabetes and myopathy in the current study,6 7 and didn't model liver enzyme elevation, since the US Food and Drug Administration recently advised that routine monitoring of liver enzymes among statin users is no longer needed (http://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm293330.htm).

The main strength of this study was our use of national data and nationally representative surveys to estimate the age-sex-race/ethnicity-specific numbers of those who are eligible for statin treatment for primary prevention of ASCVD under the 2013 Guidelines. Our study provided an improved estimate of the eligible population and the prevalence of current statin use compared with another study.2 Second, we used the best available data from the NVSS, and the NHANES Linked Mortality File (1988–2006) to estimate the age-sex-race/ethnicity-specific ASCVD mortality rates by the statin treatment groups, and the number of ASCVD deaths prevented annually under the 2013 Guidelines. Third, we used the most updated RCTs or population-based cohort study to estimate the expected additional cases of diabetes and myopathy associated with statins use.

Limitations

First, age-sex-race/ethnicity-specific ASCVD death rates were not available for different treatment groups; hence we used RRs from the NHANES III Linked Mortality Files (1988–2006) and national age-sex-race/ethnicity-specific ASCVD death rates to derive the treatment group-specific ASCVD death rates. The accuracy of such derived ASCVD death rates is unknown. Second, we assumed a uniform effect of statin treatment on reduction of ASCVD across age, sex and race/ethnicity strata, and didn't model the effects of different intensities of statin treatment on ASCVD mortality. Third, we assumed a constant effect of statin use on risk of excess diabetes across age, sex and race/ethnicity strata, though other studies suggested that excess risk for diabetes increases with age and statin dose, and that the risk might be statin specific.8 11 12 Thus, our predicted additional cases of diabetes might be conservative. In addition, the RRs of diabetes associated with statins use were considerably higher in the population-based cohort studies compared with these from RCTs.14 15 Fourth, several meta-analyses using RCTs suggest that the incidence of myopathy is no more prevalent between treatment arms,4 5 7 or found only a small increased risk of myopathy.38 However, population-based cohort studies show a significantly higher excess incidence of myopathy.4–6 9 10 13 38 One of the major challenges in the assessment of statin-associated myopathy is the absence of validated definitions.39 40 Several studies have suggested that the paucity of adverse effects using RCTs might not be generalisable to the population, because patients with complications were often excluded from trials, and the trials tended to have short durations with limited power to detect adverse events.6 9 10 13 39 41 However, other study suggested that the observational studies might substantially overestimate the treatment effect as compared with the subsequent evidence from RCTs.42 Therefore, for comprehensive assessment, our study presented population-based and RCT-based estimates. Fifth, the CIs of our results included only the uncertainty in the relative risk of statins use on mortality, and the excess incidence of adverse side effects associated with statins use, but not the uncertainty in the estimated eligible population or the stochastic uncertainty in deaths or case numbers which likely underestimate the uncertainty for all results. Finally, because of a lack of baseline ASCVD incidence rates by treatment groups at the national level, we focused on the predicted annual ASCVD deaths prevented by statin use rather than nonfatal ASCVD events. A larger number of nonfatal ASCVD events would be prevented by statin treatment because of the larger number of nonfatal ASCVD events compared with ASCVD deaths.24

In this modelling-based study, under the 2013 Guidelines for primary prevention of ASCVD using statin therapy, up to 12.6% of total annual ASCVD deaths could be prevented among adults aged 40–75 years who are eligible for statin treatment. However, these prevented deaths could be accompanied by additional cases of diabetes or myopathy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Yuling Hong, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Contributors: QY and YZ had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. QY and WDF contributed to study concept and design. Analysis and interpretation of the data were performed by QY, YZ, CG, RM, BB, MG and WDF. QY drafted the manuscript. QY, YZ, CG, RM, BB, MG and DF critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. QY and DF provided statistical expertise. Study was supervised by QY.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Goff DC Jr., Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G et al. . 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S49–73. 10.1161/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pencina MJ, Navar-Boggan AM, D'Agostino RB Sr et al. . Application of new cholesterol guidelines to a population-based sample. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1422–31. 10.1056/NEJMoa1315665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ridker PM, Cook NR. Statins: new American guidelines for prevention of cardiovascular disease. Lancet 2013;382:1762–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62388-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF et al. . Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(1):CD004816. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finegold JA, Manisty CH, Goldacre B et al. . What side proportion of symptomatic effects in patients taking statins are genuinely caused by the drug? Systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials to aid individual patient choice. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2014;21:464–74 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Unintended effects of statins in men and women in England and Wales: population based cohort study using the QResearch database. BMJ 2010;340:c2197 10.1136/bmj.c2197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Law M, Rudnicka AR. Statin safety: a systematic review. Am J Cardiol 2006;97:52C–60C. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM et al. . Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet 2010;375:735–42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61965-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macedo AF, Taylor FC, Casas JP et al. . Unintended effects of statins from observational studies in the general population: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2014;12:51 10.1186/1741-7015-12-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter AA, Gomes T, Camacho X et al. . Risk of incident diabetes among patients treated with statins: population based study. BMJ 2013;346:f2610 10.1136/bmj.f2610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naci H, Brugts J, Ades T. Comparative tolerability and harms of individual statins: a study-level network meta-analysis of 246 955 participants from 135 randomized, controlled trials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6:390–9. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preiss D, Seshasai SR, Welsh P et al. . Risk of incident diabetes with intensive-dose compared with moderate-dose statin therapy: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2011;305:2556–64. 10.1001/jama.2011.860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang H, Plutzky J, Turchin A. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:75–6. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cederberg H, Yaluri N, Modi S et al. . Increased risk of diabetes with statin treatment is associated with impaired insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion: a 6 year follow-up study of the METSIM cohort. Diabetologia 2015;58:1109–17. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macedo AF, Douglas I, Smeeth L et al. . Statins and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: cohort study using the UK clinical practice research datalink. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2014;14:85 10.1186/1471-2261-14-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reiner Z. Statins for primary prevention: problems with cardiovascular-risk estimation? Nat Rev Cardiol 2013;10:547 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.80-c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics. Plan, and Operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III, 1988–94): Reference Manuals and Reports. Weighting and Estimation Methodology Report Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Center for Health Statistics (CDC) NCfHSN. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Questionnaires, Datasets, and Related Documentation. http://wwwcdcgov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes_questionnaireshtm (accessed Jan 2014).

- 19.Allain CC, Poon LS, Chan CS et al. . Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. Clin Chem 1974;20:470–5. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugiuchi H, Uji Y, Okabe H et al. . Direct measurement of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in serum with polyethylene glycol-modified enzymes and sulfated alpha-cyclodextrin. Clin Chem 1995;41:717–23. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972;18:499–502. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: prescription medications—drug information (RXQ_DRUG). http://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/1999-2000/RXQ_DRUG.htm (accessed May 2015). 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158 [DOI]

- 23.CDC WONDER. Multiple cause of death data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; http://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth (accessed 11 Nov 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS et al. . Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;133:e38–e360. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH et al. . Treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in adults: synopsis of the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guideline. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:339–43. 10.7326/M14-0126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reiner Z, Catapano AL, De Backer G et al. , European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation, ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) 2008-2010 and 2010-2012 Committees. ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the task force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J 2011;32:1769–818. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H et al. . European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J 2012;33:1635–701. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ray KK, Kastelein JJ, Boekholdt SM et al. . The ACC/AHA 2013 guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in adults: the good the bad and the uncertain: a comparison with ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias 2011. Eur Heart J 2014;35:960–8. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL et al. . Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation 2013;127:e6–e245. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD et al. . 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S76–99. 10.1161/01.cir.0000437740.48606.d1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magnus P, Beaglehole R. The real contribution of the major risk factors to the coronary epidemics: time to end the “only-50%” myth. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:2657–60. 10.1001/archinte.161.22.2657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stamler J, Stamler R, Neaton JD et al. . Low risk-factor profile and long-term cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality and life expectancy: findings for 5 large cohorts of young adult and middle-aged men and women. JAMA 1999;282:2012–18. 10.1001/jama.282.21.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spring B, Ockene JK, Gidding SS et al. . Better population health through behavior change in adults: a call to action. Circulation 2013;128:2169–76. 10.1161/01.cir.0000435173.25936.e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mills EJ, Wu P, Chong G et al. . Efficacy and safety of statin treatment for cardiovascular disease: a network meta-analysis of 170,255 patients from 76 randomized trials. QJM 2011;104:109–24. 10.1093/qjmed/hcq165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ridker PM, Pradhan A, MacFadyen JG et al. . Cardiovascular benefits and diabetes risks of statin therapy in primary prevention: an analysis from the JUPITER trial. Lancet 2012;380:565–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61190-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pandya A, Sy S, Cho S et al. . Cost-effectiveness of 10-year risk thresholds for initiation of statin therapy for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. JAMA 2015;314:142–50. 10.1001/jama.2015.6822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simic I, Reiner Z. Adverse effects of statins—myths and reality. Curr Pharm Des 2015;21:1220–6. 10.2174/1381612820666141013134447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L et al. , Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet 2012;380:581–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60367-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alfirevic A, Neely D, Armitage J et al. . Phenotype standardization for statin-induced myotoxicity. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2014;96:470–6. 10.1038/clpt.2014.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenson RS, Baker SK, Jacobson TA et al. . An assessment by the Statin Muscle Safety Task Force: 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol 2014;8(3 Suppl):S58–71. 10.1016/j.jacl.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joy TR, Hegele RA. Narrative review: statin-related myopathy. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:858–68. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-12-200906160-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hemkens LG, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Ioannidis JP. Agreement of treatment effects for mortality from routinely collected data and subsequent randomized trials: meta-epidemiological survey. BMJ 2016;352:i493 10.1136/bmj.i493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011684supp_appendix.pdf (667.9KB, pdf)