Abstract

Objectives

Internationally, general practitioners (GPs) are being encouraged to take an active role in the care of their patients with obesity, but as yet there are few tools for them to implement within their clinics. This study assessed the self-efficacy and confidence of GPs before and after implementing a weight management programme in their practice.

Design

Nested mixed methods study within a 6-month feasibility trial.

Setting

4 urban general practices and 1 rural general practice in Australia.

Participants

All vocationally registered GPs in the local region were eligible and invited to participate; 12 GPs were recruited and 11 completed the study.

Interventions

The Change Programme is a structured GP-delivered weight management programme that uses the therapeutic relationship between the patient and their GP to provide holistic and person-centred care. It is an evidence-based programme founded on Australian guidelines for the management of obesity in primary care.

Primary outcome measures

Self-efficacy and confidence of the GPs when managing obesity was measured using a quantitative survey consisting of Likert scales in conjunction with pro forma interviews.

Results

In line with social cognitive theory, GPs who experienced performance mastery during the pilot intervention had an increase in their confidence and self-efficacy. In particular, confidence in assisting and arranging care for patients was improved as demonstrated in the survey and supported by the qualitative data. Most importantly from the qualitative data, GPs described changing their usual practice and felt more confident to discuss obesity with all of their patients.

Conclusions

A structured management tool for obesity care in general practice can improve GP confidence and self-efficacy in managing obesity. Enhancing GP ‘professional self-efficacy’ is the first step to improving obesity management within general practice.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12614001192673; Results.

Keywords: obesity, PRIMARY CARE, self efficacy, confidence

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study used social cognitive theory which has been broadly studied in the health promotion setting.

The management of obesity is an important issue in the primary healthcare setting.

The mixed methods approach, using quantitative survey plus qualitative interviews, strengthens the study.

The small sample of self-selecting general practitioners is a limitation of the study.

Background

Throughout international healthcare systems, obesity has become an increasingly important risk factor for the development of chronic illness. The global prevalence of diabetes alone has risen from 4.7% in 1980 to 8.5% in 2014, primarily due to obesity rates.1 Obesity has an impact on the health of an individual, physically and psychologically, as well as increasing community healthcare costs and indirect economic costs.2 Approaches to assist people who are living with obesity are clearly needed.

General practitioners (GPs), also known as family doctors, have a vital role to play in health promotion for their patients.3–5 Internationally, health promotion is a fundamental component of specialty training programmes for GPs.6–9 GPs are expected to promote lifestyle measures that prevent disease and enhance health and have demonstrated previous success in this goal. For example, GPs have been instrumental in the reduction in smoking rates10 and administration of immunisation programmes,11 and are a respected source of nutrition advice.4 12 GPs regularly provide lifestyle advice to patients when managing chronic illnesses such as diabetes, heart disease and arthritis.13

The majority of obesity management interventions in primary care focus on the GP delegating appropriate care to other health practitioners or into external services.14 Despite this, there are many reasons why an individual patient may prefer to see their GP for obesity management rather than an external provider. Cost, patient preference and, particularly in rural settings, access and availability are recognised as factors influencing patient preference for management within general practice.5 However, with respect to obesity management, GPs have reported low confidence in their ability to have an impact on their patients' outcomes.15 Reasons for this include lack of consultation time, feeling poorly trained in this clinical area and being unconvinced that their intervention will change patient behaviour.15

The ‘5As’ is generally the approach recommended to GPs for structuring the management of patients living with obesity.16 This framework encourages GPs to ‘Ask’ permission from the patient, ‘Assess’ the individual, provide ‘Advice’ on health impacts and treatments available, ‘Agree’ with the patient on the best way forward and ‘Assist’ them in accessing the services they need.16 A cross-sectional analysis of consultations using the 5As approach has demonstrated that GPs are less likely to ‘Assist’ and ‘Arrange’ and more likely to only ‘Ask’ and ‘Assess’.16 It is reported that patients who receive care that includes the ‘Assist’ and ‘Arrange’ components of the 5As framework are more likely to change their behaviour.17 Thus, it is suggested that GPs require support to provide care that incorporates all five ‘As’. Although this framework may be simplistic and is undoubtedly influenced by a patient's motivation to change,18 it continues to be the most referenced approach in the literature.16

Social cognitive theory (SCT) links self-efficacy to an individual's health behaviours and lifestyle.19 Traditionally, it is used in health promotion fields to explain a patient's ability to start and sustain new habits. Change occurs through a patient's belief that they can perform the required new behaviour (efficacy expectation) and that this new behaviour will lead to the desired health outcome (outcome expectation). The strongest influence on self-efficacy is ‘performance mastery’, in which the experience of having a successful outcome from a personal action provides confidence in one's ability.19

GPs provide interventions that enhance ‘patients' self-efficacy’ to achieve behaviour change. It is probable that GPs with low confidence in providing an intervention would have difficulty in supporting patients to take control of their own health. Confidence is distinct from self-efficacy in that self-efficacy is a concept bound in theory that describes levels of belief as well as capability, whereas confidence is a non-specific term for describing someone's belief in a thing.20 The likelihood of patient behaviour change is therefore related to the GPs' ‘professional self-efficacy’ to deliver an intervention. For that reason, it is important to address GPs' ‘professional self-efficacy’ as a precondition for promoting self-efficacy in patients.

SCT can also provide a useful theoretical framework for understanding GPs' views on obesity management.19 A GP who has low self-efficacy to assist patients is likely to be heavily influenced by their previous experience of poor outcomes.15 Efficacy expectation from SCT can be used to describe the GP's belief that they have the skills to provide obesity management for a patient. Outcome expectation from SCT can be related to the GP's belief that their management will lead to patient behaviour change. We hypothesise that providing GPs with a ‘performance mastery’ experience is likely to affect their self-efficacy for assisting patients living with obesity.

The Change Programme is a GP-delivered weight management programme that was developed based on Australian guidelines21 for the management of obesity in primary healthcare.22 The programme consists of a GP handbook, patient workbook and computer template.23 The suggested schedule is appointments every 2 weeks for 3 months followed by less frequent consultations for up to 2 years. The Change Programme is based on one of the pillars of general practice—‘patient-centredness’. For this reason, there are no directive patient goals. For each patient, the GP works with them as an individual. Some will have goals around physical activity, nutrition, for others, it will be time management and social connection. The programme is based on principles of self-management24 in which the enhancement of a patient's ability to self-care reduces the consequences of living with a chronic illness, and capitalises on the therapeutic potential of being cared for by a regular health practitioner.25

The aim of this study was to describe the impact of participating in a pilot intervention for obesity management, The Change Programme, on the self-efficacy and confidence of Australian GPs.

Methods

This mixed methods study of GP self-efficacy was embedded within a 6-month pilot study of weight management in general practice. The ANU Human Research Ethics Committee approved this study. Informed, written consent was obtained from each of the participants. Approximately 700 local GPs on the contact list of the academic unit of general practice were invited to participate in the study. We aimed to recruit 10 GPs working in 5 different general practices for this initial pilot study and this was achieved within 4 days. We recruited GPs in the order that they expressed interest. Once five general practices were recruited, we ceased accepting expressions of interest. Within these 5 general practices, 12 self-selecting GPs were recruited and then each recruited at least 2 adult patients from those that presented to their practice for any reason.

The patients initially attended appointments every 2 weeks, with less frequent appointments as the programme continued. The patient handbook contains factsheets with information on obesity, worksheets based on cognitive–behavioural therapy and mindfulness, nutritional and physical activity diaries, and worksheets to record goal setting. The consultation content was directed by individual patient needs and included nutrition, physical activity and behavioural support management (eg, stimulus control, goal setting, self-monitoring, cognitive restructuring, problem solving). The GPs were not directed as to whether they should complete the patient handbook within consultation time, or set it as work to do between sessions. The GPs were not offered any training beyond the written handbook as in earlier qualitative work GPs stated they did not want a programme that required additional training.23

Evaluation of the study outcomes included a quantitative survey consisting of Likert scales in conjunction with pro forma interviews. The GPs were also asked to complete a survey containing questions related to self-efficacy, each rated on a four-point Likert scale. A four-point Likert scale was chosen to avoid having a middle response. The survey was based on validated tools for self-efficacy26–28 and has been published in full previously.15 Likert net stacked distribution graphs were used to compare the pre and postsurvey results as they provide an excellent graphical representation of data. Hypothesis testing was not completed due to the small sample size and the graphs should be considered as descriptive, non-inferential statistics of change.

The survey was used as a platform for interviews conducted with GPs at the initiation and conclusion of the pilot intervention; changes in the GPs' confidence, clinical practice and sense of self-efficacy were discussed. Pro forma interviews were conducted by a GP researcher in a location convenient to the GP participants. The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcribing service. Two authors (ES, NE) independently reviewed deidentified transcripts in Microsoft Word for three preidentified themes: confidence, self-efficacy and change in clinical practice. These themes were based on SCT and the pro forma interviews were structured to gather this information. The only other information that was offered in the interviews was possible improvements to The Change Programme and this has been presented elsewhere.29 The review findings were discussed between the two authors until consensus was reached.

The qualitative results related to GP self-efficacy at the beginning of the pilot have been previously reported.15 This paper will report on the self-efficacy questionnaire responses from the GPs at the beginning and end of the 6-month pilot, as well as the qualitative interview data from the end of the pilot.

Results

The 12 GPs practised in 5 different general practices, 1 rural and 4 urban, and had between 4 and 30 years clinical experience. One GP went on unexpected leave and did not recruit any patients, while another GP recruited three patients. All of the GPs who recruited patients were interviewed and completed the survey at the end of the trial.

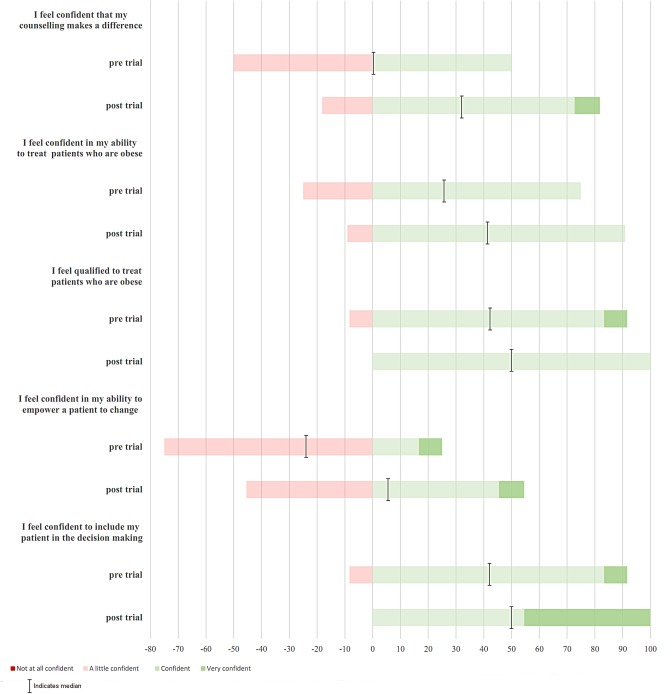

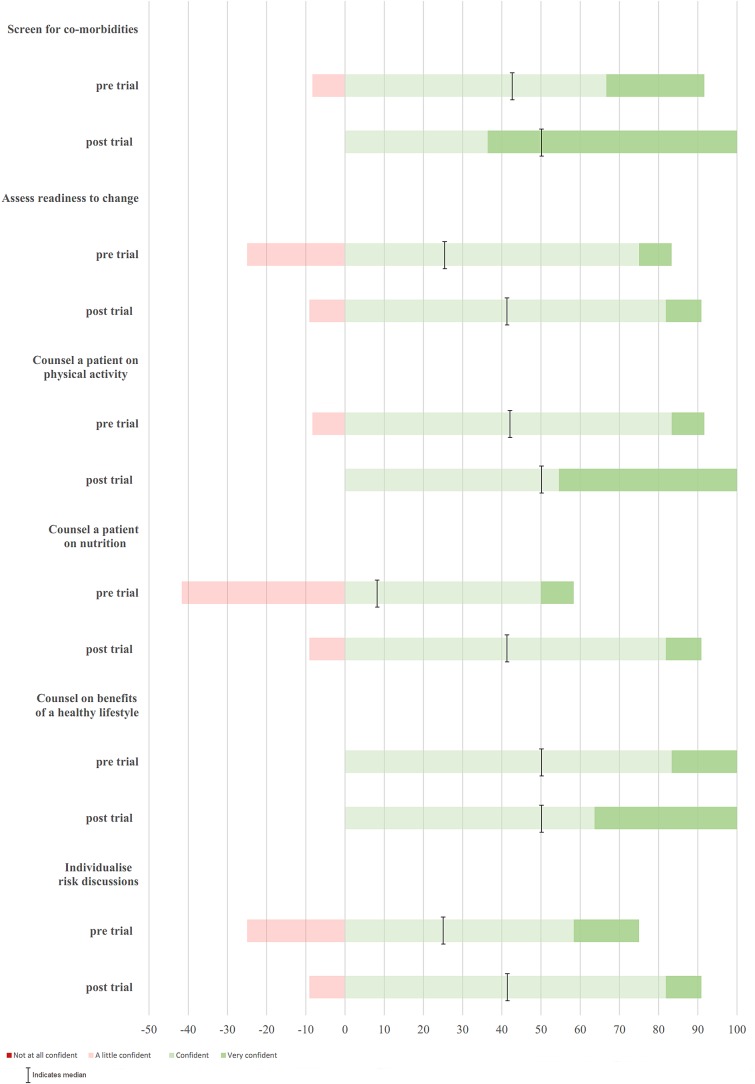

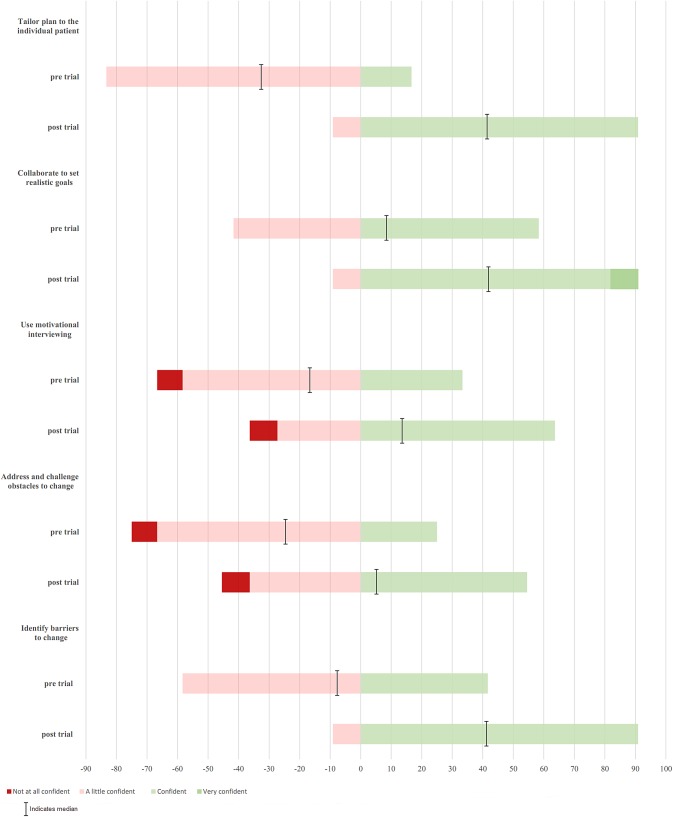

There was an improvement in the Likert scale values across almost all indicators (see figures 1–3) in the postpilot surveys. In each figure, the median response is indicated by the black line and the width of the coloured bar represents the mode. Outcome expectations, in which the GP is confident that their approach to obesity will lead to better health outcomes, are demonstrated in figure 1. Both the median score for the GPs' perceptions that counselling made a difference to patient behaviour and the median score for belief that the GP can empower a patient to change their behaviour indicated improvements in GPs' expectations of outcomes.

Figure 1.

Survey results for general practitioners (GPs) pre and postpilot study relating to GP outcomes expectations for managing adult patients with obesity. Dark red, a little confident; light red, not at all confident; light green, confident; dark green, very confident. Black line indicates the median value.

Figure 2.

Survey results for general practitioners (GPs) pre and postpilot study relating to GP efficacy expectations in the ‘Assess’ and ‘Advise’ categories of the 5As framework. Light red, a little confident; dark red, not at all confident; light green, confident; dark green, very confident. Black line indicates the median value.

Figure 3.

Survey results for general practitioners (GPs) pre and postpilot study relating to GP efficacy expectations in the ‘Assist’ and ‘Arrange’ categories of the 5As framework. Light red, a little confident; dark red, not at all confident; light green, confident; dark green, very confident. Black line indicates the median value.

Efficacy expectations, in which the GP is confident that they can assist a patient to change their behaviour, are demonstrated in figures 2 and 3. Figure 2 focuses on the ‘Assess’ and ‘Advise’ phases of the 5As framework with improvement in the number of GPs who agree or strongly agree, particularly for nutrition counselling. Figure 3 has items relating to the ‘Assist’ and ‘Arrange’ phases of the 5As with improvements in the median Likert score across all questions, including identifying barriers, tailoring a plan to an individual and addressing obstacles to change.

The qualitative interview data supported the survey results with most GPs reporting an improvement in their overall confidence when managing patients with obesity.

I think I'm more confident to know where to start in assessing the patient in terms of sort of things that are contributing to overweight and obesity, and their readiness for change, and then starting to set some goals with them and working towards those goals, and being able to give them more specific suggestions for change and what they might work on. (GP-D)

Specifically, some GPs stated that the access to a structured toolkit helped them to feel more confident in their management.

I think it's given me some [confidence]…perhaps some more tools and resources, which has been helpful. (GP-H)

The GPs also reported an improvement in self-efficacy for obesity management. This was due to seeing changes in their patients which then gave them confidence in the work they were doing.

I feel very encouraged by the results. I think the results [have] been good, and … I think I was effective in these three patients. (GP-L)

In the interviews, GPs recognised a change from their usual clinical practice after taking part in the pilot study. Examples given included an increase in their clinical knowledge, improvements in individualising care and increasing frequency of consultations.

I talk a bit more about the plateauing, because that was something I wasn't that aware of. And so that's really helpful, I think, in talking to other [patients]. (GP-SP)

I think it's just a general change in my practice over the last period in that being less focussed on the numbers goals [i.e. kilogram weight loss] and bit more focussed on individualising the care. (GP-SE)

That's the main thing that I'm going to change in the future, is just a more regular quick face-to-face interaction, so they feel accountable. (GP-P)

Additionally, some GPs reported that they had already changed their practice with other patients who were not engaged in the pilot trial. Some GPs reported feeling more comfortable talking to other patients about obesity, and applying some aspects of The Change Programme to other patients.

I'm also taking a lot more waist circumferences now. And I'm weighing people more. In general in my practice… I used to be a little bit uncomfortable with it, and now I'm more comfortable saying do you mind hopping on the scale, let's see what you weigh. Doing a waist circumference … And then opening up the conversation…and people are actually relieved and grateful when you do that for them. And I guess before I thought they would be more embarrassed or upset, when they're not, that's what they want. They talk to me about it. (GP-SP)

Discussion

We have shown an increase in GPs' confidence and self-efficacy by providing them with a structured toolkit for the management of obesity. This increase was demonstrated in the results from the quantitative survey as well as the qualitative interview data. In the interviews, GPs identified the structure and support provided by The Change Programme materials as the key reason that they felt more confident after the pilot intervention. This improved confidence is consistent with efficacy expectations in SCT which describes a person's belief that their actions will be effective in leading to behaviour change. In this case, the GPs' actions working with a patient, resulting in the patient's behaviour change.

The most encouraging result was the change in usual clinical practice reported by the GPs in the interviews. They reported using their skills from the pilot trial with other patients outside the research setting. They were more confident to ask and assess patients for obesity management knowing they had skills to offer. This ‘performance mastery’ experience for the GPs fits with SCT. The GP has had a positive experience managing a patient with obesity leading to increased GP ‘professional self-efficacy’ to assist patients to change their behaviour. This has flowed into regular daily practice with the GPs reporting increased ease in discussing obesity and management options with patients who were not part of the pilot study.

It is notable that the ‘Assist’ items (related to goal setting, identifying barriers and using motivational interviewing techniques) on the questionnaire showed the greatest change in GP confidence. This is possibly due to the structured approach provided by The Change Programme that gave the GPs a new process for working with patients. It has been found in other obesity intervention studies in consultations that progress to the ‘Assist’ and ‘Arrange’ stages of the 5As framework are associated with the greatest patient lifestyle change.16 30 The improvement in GP confidence seen with The Change Programme leads to the GP feeling more comfortable initiating conversations and discussing management. This is the initial, critical step on the path towards facilitating actual patient behaviour change.31

Often interventions to improve GP care of patients with obesity focus on encouraging GPs to ask their patients for permission to talk about obesity.14 17 30 The approach of our pilot intervention was somewhat different where we supported GPs with the ‘Assist’ and ‘Arrange’ parts of the framework and in doing so, some GPs found their increase in confidence led to them talking to more of their patients about obesity. This alternative approach may be more successful in empowering GPs to speak to more patients about obesity as they are confident and have self-efficacy for managing patients with obesity.

The generalisability of these findings is limited by the small sample of self-selecting GPs and it is likely these GPs have a particular interest in obesity care. Further work on the effectiveness of The Change Programme should aim to recruit a broad range of GPs in different styles of practices to ensure that the programme applies to a variety of practitioners. The improvement in GP self-efficacy and confidence seen in the quantitative survey which was then supported by the qualitative data is a strength of this study.

The Change Programme focuses obesity management within the general practice setting. It is reliant on a strong therapeutic relationship between a patient and their GP. In some international primary care settings, this approach is not in line with current trends of GP care being delegated to other professionals or entirely moved out of the GP care space.32 Our findings that GP self-efficacy can be improved and their practice changed using a structured approach to obesity management are noteworthy, and the principles could be applied to suit local settings. Further study is needed to determine the cost-effectiveness of reducing fragmentation of care and whether GPs can deliver improved outcomes over the longer term for patients with obesity.

This study provides a unique insight into the possibility of changing GPs' confidence and self-efficacy for obesity management by providing them with a structured tool. By assisting them to achieve a ‘performance mastery’ experience, the GPs' confidence levels were improved to a point where they offered more to their patients outside the research setting. It is possible to improve GPs' confidence and self-efficacy for obesity management using a structured management programme.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Elizabeth Sturgiss @LizSturgiss

Contributors: ES, EH, NE, CvW and KD contributed to the design of this study. Acknowledgement to Dr Freya Ashman who collected the data. ES and NE analysed the qualitative data. EH designed the graphs for the presentation of the quantitative data. ES wrote the original draft and was responsible for reviewing each draft until finalisation. ES, EH, NE, CvW and KD contributed to the editing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute via a 2014 Foundation Grant.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The original data set is held by the Academic Unit of General Practice at the Australian National University Medical School, Canberra Hospital campus. Access to the original data by researchers outside the research team would require approval via ethics committee.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. Global report on diabetes. France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colagiuri S, Lee CMY, Colagiuri R et al. . The cost of overweight and obesity in Australia. Med J Aust 2010;192:260–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball L, Johnson C, Desbrow B et al. . General practitioners can offer effective nutrition care to patients with lifestyle-related chronic disease. J Prim Health Care 2013;5:59–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ball L, Desbrow B, Leveritt M. An exploration of individuals’ preferences for nutrition care from Australian primary care health professionals. Aust J Prim Health 2014;20:113–20. 10.1071/PY12127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansen S, Desbrow B, Ball L. Obesity management by general practitioners: the unavoidable necessity. Aust J Prim Health 2015;21:366–8. 10.1071/PY15018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice. 8th edn East Melbourne, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of General Practitioners. Healthy People: promoting health and preventing disease in RCGP Curriculum, Professional and Clinical Modules. Royal College of General Practitioners, London, 2016.

- 8.Tannenbaum D, Konkin J, Parsons E et al. . CanMEDS-Family Medicine: working group on curriculum review. The College of Family Physicians of Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Family Medicine: report of a regional scientific working group meeting on core curriculum. New Delhi: World Health Organisation, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zwar NA, Richmond RL. Role of the general practitioner in smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Rev 2006;25:21–6. 10.1080/09595230500459487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campos-Outcalt D, Jeffcott-Pera M, Carter-Smith P et al. . Vaccines provided by family physicians. Ann Fam Med 2010;8:507–10. 10.1370/afm.1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dillen SM, Hiddink GJ, Koelen MA et al. . Perceived relevance and information needs regarding food topics and preferred information sources among Dutch adults: results of a quantitative consumer study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004;58:1306–13. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris MF, Zwar NA. Care of patients with chronic disease: the challenge for general practice. Med J Aust 2007;187:104–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carvajal R, Wadden TA, Tsai AG et al. . Managing obesity in primary care practice: a narrative review. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2013;1281:191–206. 10.1111/nyas.12004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashman F, Sturgiss E, Haesler E. Exploring self-efficacy in Australian general practitioners managing patient obesity: a qualitative survey study. Int J Family Med 2016;2016:8212837 10.1155/2016/8212837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vallis M, Piccinini-Vallis H, Sharma AM et al. . Clinical review: modified 5 As: minimal intervention for obesity counseling in primary care. Can Fam Physician 2013;59:27–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rueda-Clausen CF, Benterud E, Bond T et al. . Effect of implementing the 5As of obesity management framework on provider-patient interactions in primary care. Clin Obes 2014;4:39–44. 10.1111/cob.12038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997;12:38–48. 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977;84:191–215. 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A. Self efficacy: the exercise of control. Stanford, USA: Stanford University, 1997:382. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Health and Medical Research Council. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents and children in Australia. Melbourne: National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sturgiss E, Douglas K, Kathage R et al. . A synthesis of selected national Australian guidelines on the general practice management of adult patients who are overweight or obese. Aust Fam Physician 2016;45:327–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sturgiss EA, Douglas K. A collaborative process for developing a weight management toolkit for general practitioners in Australia-an intervention development study using the Knowledge To Action framework. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2016;2:20 10.1186/s40814-016-0060-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J et al. . Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns 2002;48:177–87. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00032-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L et al. . The influence of the patient–clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e94207 10.1371/journal.pone.0094207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Block JP, DeSalvo KB, Fisher WP. Are physicians equipped to address the obesity epidemic? Knowledge and attitudes of internal medicine residents. Prev Med 2003;36:669–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jay M, Gillespie C, Ark T et al. . Do internists, pediatricians, and psychiatrists feel competent in obesity care? J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1066–70. 10.1007/s11606-008-0519-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Visser F, Hiddink G, Koelen M et al. . Longitudinal changes in GPs’ task perceptions, self-efficacy, barriers and practices of nutrition education and treatment of overweight. Fam Pract 2008;25(Suppl 1):i105–11. 10.1093/fampra/cmn078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sturgiss EA, Elmitt N, Haesler E et al. . Feasibility and acceptability of a physician-delivered weight management programme. Fam Pract 2016:cmw105 10.1093/fampra/cmw105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexander SC, Cox ME, Boling Turer CL et al. . Do the five A's work when physicians counsel about weight loss? Fam Med 2011;43:179–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sim M, Wain T, Khong E. Influencing behaviour change in general practice. Part 1—brief intervention and motivational interviewing. Aust Fam Physician 2009;38:885–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aveyard P, Lewis A, Tearne S et al. . Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: a parallel, two-arm, randomised trial. Lancet 2016;388:2492–500. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31893-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]