Abstract

Objectives

Laser photocoagulation surgery is a routine treatment for threshold retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). However, little is known about which anaesthesia protocols provide efficient pain control while minimising exposure risk to vulnerable infants. In this study, therefore, we assessed the efficacy and tolerability of multiple anaesthesia techniques used on premature infants during laser therapy.

Design and main outcome measures

Anaesthesia modalities consisted of topical eye drops anaesthesia, general anaesthesia and intravenous fentanyl sedation with mechanical ventilation. Laser treatment efficacy and detailed operative information were retrospectively and consecutively analysed. Cardiorespiratory stability was assessed and compared. The Neonatal Pain Agitation and Sedation Scale (N-PASS) was used to evaluate tolerability in infants that underwent intravenous fentanyl sedation.

Results

97 cases of prematurity were included in this study. In 94/97 (96.9%) cases, vascular proliferation regressed. In the topical anaesthesia groups, the ophthalmologist needed 12–16 min more to complete the treatment. During the 3 postoperative days, topical anaesthesia demonstrated the greatest instability; 4/31 (12.90%) infants in this group suffered from life threatening events requiring resuscitation. The only instability observed in general anaesthesia and fentanyl sedation was attributed to difficulty in extubating within 24 hours after surgery. During laser therapy, the N-PASS score increased to 1.8 in the fentanyl sedation group.

Conclusions

Topical anaesthesia was associated with more cardiorespiratory instability during ROP laser treatment. While general anaesthesia and fentanyl sedation had similar postoperative cardiorespiratory results, the latter demonstrated acceptable pain stress control. However, the difficulty of weaning off mechanical ventilation in some cases after surgery needs to be addressed in future studies.

Keywords: retinopathy of prematurity, laser, stress response, fentanyl, cardio-respiratory

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was conducted in a relatively large population involving retinopathy of prematurity treatment, and the results demonstrated the difference in cardiorespiratory instability associated with a variety of anaesthesia protocols in preterm infants.

Our study results add to a growing body of data that confirm the association between topical anaesthesia and postoperative events in laser therapy. Topical anaesthesia is the major anaesthesia module in developing countries; however, the potential side effects induced by topical anaesthesia are often underestimated.

Our analyses of data from one of the largest study samples to date show acceptable pain control by fentanyl sedation in the setting of laser treatment for preterm infants, showing a similar cardiorespiratory score compared to general anaesthesia.

Our study had a number of limitations. The retrospective nature of our investigation did not allow us to determine causality of postoperative cardiorespiratory instability. There are, however, a number of biologically plausible aetiologies. Lastly, Neonatal Pain Agitation and Sedation Scale scores are not available for all three anaesthesia groups (topical, fentanyl, general), thus it is not possible to comment on any difference in pain control.

Introduction

Improved survival rates among premature infants have resulted in increases in the incidence of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) and consequently a growing number of cases are requiring laser photocoagulation. A quiet and immobile patient is necessary if treatment is to be successful. However, the sedation or analgesia of preterm infants remain a great challenge for paediatric anaesthetists, especially when cardiorespiratory instability is also considered. The oculocardiac reflex is well developed in all infants and premature infants tend to be more vulnerable than their full term counterparts to stressful procedures.1 Accumulating publications have revealed the systemic complications associated with ROP screening and treatment in preterm infants.2 3 Nevertheless, little has yet been discussed as to which anaesthetic technique best minimises these complications while maximising benefits. Thus, there is an urgent need to evaluate the differential outcomes across multiple anaesthesia modalities for these high risk infants.

In Guangdong Women and Children's hospital, there has been a change of anaesthesia practices for ROP treatment from topical anaesthesia to general anaesthesia and, afterwards, to intravenous fentanyl sedation plus mechanical ventilation. The aim of this consecutive, non-randomised, observational study was to assess the efficacy and complications of laser treatment under different anaesthesia techniques. The Neonatal Pain Agitation and Sedation Scale (N-PASS) was also used to evaluate the tolerance of fentanyl sedation.

Subjects and methods

Cardiorespiratory conditions in infants undergoing retinal laser photocoagulation of threshold ROP over 1 year and 6 months to 2014 were collected from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) medical records and retrospectively evaluated. Operative data were recorded prospectively. Written informed parental consent for ROP screening and treatment were obtained for all infants. The ROP screening protocol and laser treatment criteria met the current national and early treatment for ROP guideline.4 5

The subjects were divided into three independent groups according to the anaesthesia strategies. Group A comprised infants receiving topical proxymetacaine anaesthesia. Group B comprised infants treated with intravenous fentanyl sedation. Fentanyl was administered at a dose of 2 µg/kg and was intravenously delivered by a pump over 20 min before treatment and continuously infused at a rate of 2 µg/kg/hour during treatment. Group C consisted of babies under general anaesthesia using halothane inhalation and muscle relaxation in the operating theatre. Infants in groups B and C were intubated and mechanically ventilated using intermittent positive pressure ventilation mode unless a higher level of ventilation support had been applied before the operation. The baby was swaddled and put on a radiant warmer. A pacifier was used if accepted. Assistants were present to maintain the position of each baby’s head. Apnoeic or bradycardia episodes were eliminated with stimulations delivered by neonatal nurses or assistants on site.

The total study population was heterogeneous in terms of overall cardiorespiratory conditions and other pathologic situations. Respiratory support methods, respiratory rate and heart rate, transcutaneous oxygen saturation and other information had been recorded bi-hourly in the NICU monitoring chart and the recording frequency was increased to every half an hour during laser treatment and 2 hours afterwards. This approach enabled us to explore the cardiorespiratory index (CRI) and make the comparison in terms of cardiorespiratory stability between different anaesthesia modalities. The CRI was designed by Haigh and became a widely acceptable scoring method to show changes in the overall systemic status of infants on a day-to-day basis.6 Descriptions of the CRI system are shown in table 1. A score >1 indicates decreased stability and a score <1 indicates increased stability.

Table 1.

Cardiorespiratory stability scoring system

| Score | Designation | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Improved from baseline | Decreased oxygen requirement (>20% relative change in FiO2) |

| 1 | No change from baseline | |

| 2 | Mild instability | Increased oxygen requirement (20–50% relative change in FiO2), more apnoeas and/or bradycardias responding to gentle stimulation (100% increase or 5 if none before) |

| 3 | Marked instability | Increased oxygen requirement (>50% relative change in FiO2), more apnoeas and/or bradycardias responding to vigorous stimulation (100% increase or 5 times/episodes if they haven't had this problem before), higher ventilation requirement |

| 4 | Life threatening event | Requiring emergency resuscitation (eg, intubation, suction/bag mask oxygen, cardiac massage) |

FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen concentration.

In our NICU policy, an apnoea spell was defined as no respiratory activity for a period of 20 s or more. Bradycardia was defined as a heart rate of 90 beats/min or less. In most cases, the ventilation support after extubating remained at the same level as it was before laser treatment for at least 24 hours unless indicated by the attending neonatologist. An upgrade in ventilation mode was described as a major instability. An example of such an upgrade would be an infant going from being self-ventilated in air to requiring nasal cannula oxygen or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) due to desaturation, an apnoea or bradycardia episode, etc.

N-PASS scores were obtained in the infants in group B, who underwent intravenous fentanyl sedation every 20 min, administered by the same attending neonatologist. The N-PASS score includes physiological and behavioural indicators ranging from 0 to 10 and reflects neonatal pain and agitation, as shown in table 2. As for preterm infants, this system adjusts the pain score in order to approximate the response of term infants by adding points to the calculated result on the basis of gestational age.

Table 2.

Neonatal Pain Agitation and Sedation Scale

| Sedation |

Sedation/pain | Pain/agitation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment criteria | −2 | −1 | 0/0 | 1 | 2 |

| Crying irritability | No cry with painful stimuli | Moans or cries minimally with painful stimuli | No sedation/no pain signs | Irritable or crying at intervals Consolable |

High-pitched or silent-continuous cry Inconsolable |

| Behaviour state | No arousal to any stimuli No spontaneous movement |

Arouses minimally to stimuli Little spontaneous movement |

No sedation/no pain signs | Restless, squirming Awakens frequently |

Arching, kickingConstantly awake or arouses minimally/no movement (not sedated) |

| Facial expression | Mouth is lax No expression |

Minimal expression with stimuli | No sedation/no pain signs | Any pain expression intermittent | Any pain expression continual |

| Extremities tone | No grasp reflex Flaccid tone |

Weak grasp reflex ↓muscle tone |

No sedation/no pain signs | Intermittent clenched toes, fist or fingers splay Body is not tense |

Continual clenched toes, fists, or finger splay Body is tense |

| Vital signs HR, RR, BP, SaO2 | No variability with stimuli Hypoventilation or apnoea |

<10% variability from baseline with stimuli | No sedation/no pain signs | ↑↑10–20% from baseline SaO2 76–85% with stimulation-quick recovery↑ | SaO2 <75% with stimulation-slow recovery↑ Out of sync with vent |

The pain score is adjusted in premature infants according to gestational age categories: add 3 to infants <28 weeks; add 2 to infants 28–31 weeks; add 1 to infants 32–35 weeks.

BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; RR, respiratory rate; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation.

All treatments were carried out by the same experienced ophthalmologist specialised in ROP. Pupils were dilated with topical tropicamide eye drops (0.5% tropicamide and 0.5% phenylephrine) three times before the examination at an interval of 20 min. Treated eyes received steroid/antibiotic drops (tobramycin eye drops, 0.3% tobramycin/0.1% dexamethasone) for 3 days after photocoagulation. After the local anaesthesia drops (proxymetacaine 0.5%) were administered 5 min before and immediately before the treatment, a sauer infant lid speculum was inserted and the retina was visualised using a 30 dioptre lens and an indirect ophthalmoscope. Photocoagulation was performed using the binocular indirect diode laser (Vitra multispot laser, Quantel Medical, France). When necessary, a Flynn indenter was used to visualise the peripheral avascular retina. A sterile gauze square was temporarily placed over the eye not undergoing treatment at that time.

The ethics committee of Guangdong Province Women and Children's Hospital waived and approved this study as it was an observational and audit study.

Statistical analysis

One way and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyse the CRI in the three treatment groups. Mann-Whitney U-tests were used to compare the parameters between different anaesthesia groups. A value of p≤0.05 was considered to be significant. Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient was performed regarding N-PASS and other treatment variables in the fentanyl analgesia group.

Results

Cohort

Laser treatments were performed in a total of 97 premature neonates between July 2013 and December 2014. Among the subjects, 31 (31.9%) infants were under topical eye drops anaesthesia; 47 (48.5%) infants were under fentanyl intravenous infusion and incubation by a neonatologist in the neonatal care unit, which comprised the great majority of the subjects; and 19 (19.6%) infants received general anaesthesia administered by a paediatric anaesthetist in the operating theatre. There was no significant group difference for gestational age, birth weight, postpartum age or weight at treatment and number of laser burns for each eye, as shown in table 3. Notably, ophthalmologists needed 12–16 min more (Mann-Whitney's U test, p=0.03) to complete the procedure compared to fentanyl or general anaesthesia. The secular trend within group analysis indicated no significant effect on time required to complete the treatment due to accumulating experience of the surgeon.

Table 3.

Demographic data for the study population, shown as mean (range)

| Group A | Group B | Group C | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of infants | 31 | 47 | 19 | N/A |

| Anaesthesia modality | Topical proxymetacaine | Fentanyl analgesia/incubation | General anaesthesia | N/A |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 28 (26–30) | 28 (25–30) | 27 (25–29) | 0.58 |

| Birth weight (g) | 890 (760–1210) | 870 (630–1150) | 820 (660–1070) | 0.19 |

| Postpartum age at treatment (weeks) | 37 (33–44) | 36 (34–42) | 35 (31–39) | 0.46 |

| Weight at treatment (g) | 1920 (820–3260) | 1830 (1260–3150) | 1760 (910–2880) | 0.08 |

| Duration of treatment (min) | 68 (42–102) | 56 (35–74) | 52 (29–68) | 0.03* |

| Number of laser burns per eye | 960 (480–2420) | 1066 (570–2230) | 1120 (680–1850) | 0.12 |

*p<0.05, difference between groups. Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

ROP treatment efficacy

The power of laser burns was 230–520 mW and the duration of burns was 200–300 ms.

In 94 (96.9%) cases where planned doses of laser burns were delivered, vascular proliferation regressed without any further treatment. Two cases progressed to stage 4b ROP and were transferred to obtain vitreolensectomy. Eleven (11.3%) cases needed a second treatment because of proliferation progression, and another four (4.1%) cases received a total of three photocoagulations. Intravitreal bevacizumab therapy were applied to eight (8.24%) infants.

CRI and complications

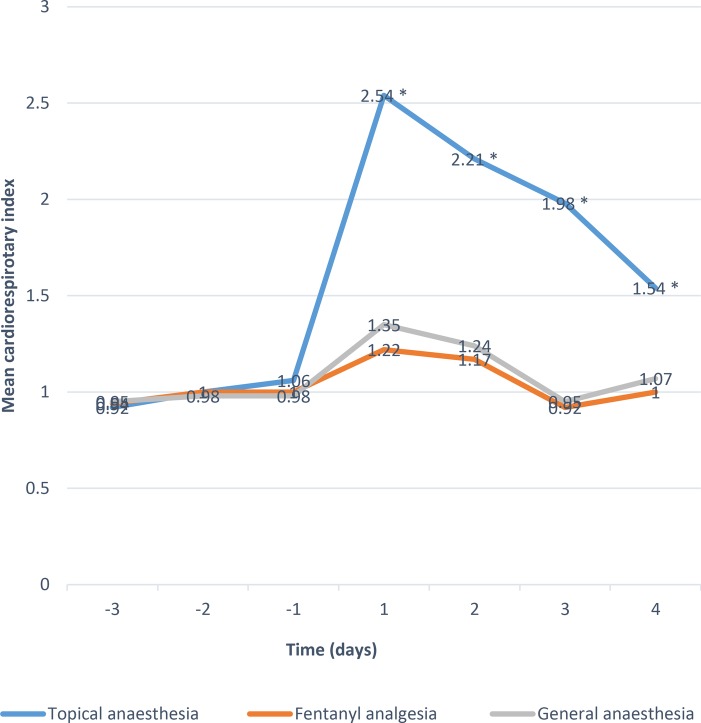

The mean CRIs indicating cardiorespiratory stability were plotted pre- and postoperatively on a day-to-day basis (figure 1). While good baseline stability was obtained in each group, topical anaesthesia showed greatest instability in each consecutive day after laser treatment (p<0.05). Scores in groups B and C showed no difference postoperatively. Specifically, 10 out of 31 infants (32.25%) in group A showed mild instability, eight (25.8%) infants showed marked instability during the first 3 days after laser treatment, and four (12.90%) infants suffered from life threatening respiratory distress or hypoxia requiring resuscitation. Among the four infants who underwent resuscitation, three were intubated and mechanically ventilated for more than 48 hours and one infant failed to survive 4 days later because of fatal pneumorrhagia. Laser treatment was terminated and rescheduled in those four infants after resuscitation. Another four (12.9%) infants in group A developed apnoea, bradycardia or deceased cutaneous oxygen saturation in response to bag and mask oxygen during the treatment.

Figure 1.

Mean cardiorespiratory index scores for the three anaesthesia techniques (topical, fentanyl, general) from 3 days before laser treatment to 4 days postoperatively. *Indicates p<0.01 vs fentanyl and general anaesthesia.

Eight (17.02%) infants under fentanyl sedation and incubation showed mild instability. Two (4.2%) infants showed marked instability which was attributed to difficulties extubating within 24 hours after the procedure, and were maintained on mechanical ventilation for 2–3 days following intubation. The same situation occurred in two (10.5%) infants in group C, who were maintained on mechanical ventilation for another 1–2 days. The rest of the infants in groups B and C were extubated successfully within 8 hours after the elective intubation.

Excessive head movement increased in infants under topical anaesthesia. If the severity of the head movement rendered the treatment unachievable or it was determined that the infant was unable to tolerate the treatment, the treatment was paused, the infants were settled by re-swaddling, they were administered an oral dose of 25% glucose, and the supplemental oxygen concentration was increased. A second dose of proxymetacaine was given before resuming laser treatment. The surgeon reduced the laser power to the minimum effective power afterwards, to minimise discomfort. Despite head movement complications, all such treatments were eventually completed successfully.

Pain scores

The tolerability of laser treatment was evaluated using N-PASS. In our survey, N-PASS was applied in 47 infants under fentanyl sedation. There was no statistically significant correlation between the mean pain score and postpartum age at treatment, duration of laser treatment, or number of laser burns. The mean baseline pain score obtained before treatment was 0.2 (SD 0.8; range −1–2). During laser therapy, there was a slightly increased mean pain score up to 1.8 (SD 1.1; range 1–4.6).

Discussion

In 1993, a nationwide study targeting 118 NICUs in Britain indicated that treatment of ROP was subjected to large regional variation in terms of anaesthetic support.7 More than two decades after, the situation had not changed much.8 Though it is well established through many studies that premature infants perceive painful stimuli and that ROP screening is a necessary but recognisably painful procedure, there are still no specific guidelines as to which type of anaesthesia is preferable to others.9 This lack of knowledge is especially problematic in low and middle income (developing) countries with limited health resources, where even normative ROP screening is still challenging in some places. These populations have higher threshold ROP morbidity10–12 and thus laser treatment is most critical, yet there are fewer resources available to address the issue. Hospitals in low and middle income countries often require the transfer of cases of prematurity with threshold ROP to tertiary hospitals to receive timely laser treatment. Therefore, safe and applicable laser treatment anaesthesia manipulation is of great importance to ensure that each case receives the optimal intervention.

In Guangdong Women and Children's hospital, prompted by neonatologists' feedback regarding infant stress, systemic complications, and practical operation considerations, the anaesthesia practice during laser treatment was changed from topical anaesthesia to general anaesthesia and, most recently, to intravenous analgesia and artificial ventilation. With a CRI scoring system, our research team was able to undertake comparisons of postoperative systemic outcomes. As demonstrated here, the variation in terms of the infants' medical situation occurred within groups rather than between groups. No infant showed instability at the time of laser treatment. However, despite all infants receiving the same postoperative management, systemic complications arose in some cases immediately after starting surgery and lasted as long as 4 days after surgery, indicating that the complications were associated with laser therapy.

Laser treatment has become the predominant modality for the management of threshold ROP. This involves manipulation of the globe in the form of lid retraction and scleral indentation. The bright light and retinal burn are stated as painful even for adults, let alone infants, regardless of whether or not a topical anaesthetic has been administered.13 14 In 1997, using CRI, Haigh and colleagues illustrated that topical anaesthesia alone was associated with more severe cardiorespiratory complications during and after ROP surgery.6 Since then, a few small sample surveys have been conducted, resulting in the conclusion that topical anaesthesia alone might not adequately accommodate infants.15 16 On the other hand, it was thought that sight-threatening foveal burns may occur because ocular akinesia cannot be induced by topical anaesthesia. Although there was more expertise available for paediatric general anaesthesia, the multiple unaddressed issues associated with its use left topical anaesthesia to be the preferred option in most neonatal care units in China and other low and middle income countries due to its easy access.

The present study showed that in addition to decreased systemic stability, the ophthalmologist needed 12–16 min more on average to complete the treatment under topical anaesthesia compared to fentanyl or general anaesthesia. In the case where the head movements persisted, it was more challenging to continue the surgery. Notably, prolonged treatment is speculated to be more painful for infants.

Several studies have been published in regards to various anaesthesia protocols in the treatment of ROP. A prospective study in which the postoperative course was examined showed no difference in safety parameters between fentanyl infusion and morphine, although complication rates suggested that fentanyl may be safer in terms of overall worsening of ventilation status and temperature instability.17–19 In the present study, general anaesthesia and fentanyl sedation were well tolerated. In these two groups, no life-threatening events occurred. The instability was mainly attributed to delayed extubation: 4.2% of infants in the fentanyl group and 10.5% of infants in the general group needed to be maintained on mechanical ventilation for 1–2 days postoperatively. It is of note that most of the premature infants had been weaned off respiratory support by the time threshold ROP occurred. Having a fragile cardiorespiratory system made the episodes of bradycardia and apnoea more common when encountering a stressful event, such as laser treatment. Advanced ventilation diminished the bradycardia and apnoea spells, perhaps by protecting them from hypoxia. However, further efforts are needed to avoid prolonged periods of ventilation after treatment.

In consideration of an infant's poorly developed neurological capacity and resultant inability to present with behavioural or physiological signs of disturbance (eg, pain expression), N-PASS adjusts the score on the basis of gestational age, making it a reliable and internationally accepted method to evaluate the neonatal pain.20–23 Several studies reported that the N-PASS score was 7.5 during ROP screening under topical anaesthesia in premature infants, 3.9 during heel-stick, 2.7 during sub-tenon anaesthesia, or ranged from 4.75 to 7.11 after general surgery in term neonates.20 24 25 Compared to these data, the score from our study of 1.8 for fentanyl analgesia indicates a relatively tolerable level of pain.

ROP screening is carried out in obstetric and general hospitals of all levels. In the cases where ROP treatments were carried out under general anaesthesia, infants had to be transferred to a higher level hospital with on-site paediatric anaesthesia. Such transfers are setbacks, giving rise to excessive financial and manpower costs. On the other hand, if fentanyl is used, laser treatment could be carried out everywhere, the patients would not need to be transferred back and forth, and thus financial and manpower costs could be minimised. In contrast, the portability of modern lasers has enabled treatment for ROP to be performed in NICUs, with the baby under the supportive care of a neonatologist. Therefore, fentanyl sedation has, in our experience, been sustainable and highly efficient. Not only is it related to a more stable cardiorespiratory condition during and after laser treatment, but it also affords more autonomy to the ophthalmologist in carrying out a timely intervention. More importantly, infants under fentanyl analgesia and mechanical ventilation displayed satisfactory N-PASS scores.

As this is a retrospective study, there are unresolved questions in terms of the optimal fentanyl dose to use, how to avoid possible oversedation and postoperative pain management or prolonged ventilation after treatment.26 Another limitation of this study is the absence of N-PASS scores for patients under topical and general anaesthesia. These are issues which would need to be addressed by a prospective study.

In conclusion, our results indicate that topical anaesthesia is associated with more cardiorespiratory instability during and after laser treatment. General anaesthesia or intravenous fentanyl analgesia plus mechanical ventilation are safe anaesthesia modalities, while the latter provides satisfactory pain relief in prematurity. Fentanyl analgesia appears to be the most practical in terms of time and financial costs; with fentanyl anaesthesia, ophthalmologists could carry out ‘day-case’ surgery in rural or obstetric hospitals with a portable indirect ophthalmoscope-mounted diode laser.

Footnotes

Contributors: J-bJ and Z-wZ conceived the study. X-qL and CN contributed to developing the statistical methodology for the study. Y-lW, J-wZ prepared the data for analysis. All authors contributed to covariate selection and interpretation of the results. J-bJ prepared the first draft of the paper. Randy Strauss took the responsibility to revise the manuscript.

Funding: All phases of this study were supported by Guangdong Provincial Scientific Institute Supportive and Innovative Program (2015B 070701008) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (71173055, 2011).

Competing interests: None declared.

Parental consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The ethics committee of Guangdong Province Women and Children's Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.MacLaren AT, Peters C, MacDonald PD. Nasal CPAP and preterm bradycardia: cause or cure. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014:pii: bcr2013202289 10.1136/bcr-2013-202289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen AM, Cook N, Harris MC et al. The pain response to mydriatic eye drops in preterm infants. J Perinatol 2013;33:462–5. 10.1038/jp.2012.149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang JB, Zhang ZW, Zhang JW et al. Systemic changes and adverse effects induced by retinopathy of prematurity screening. Int J Ophthalmol 2016;9:1148–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Experts Group for the Guideline of Prevention and Treatment of Retinopathy of Premature Infants. [Guidelines for therapeutic use of oxygen and prevention and treatment of retinopathy in premature infants]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 2007;45:672–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Good WV, Hardy RJ, Dobson V et al. , Early Treatment of Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Final visual acuity results in the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity study. Arch Ophthalmol 2010;128:663–71. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haigh PM, Chiswick ML, Donoghue EP. Retinopathy of prematurity: systemic complications associated with divergent anaesthetic techniques at treatment. Br J Ophthalmol 1997;81:283–7. 10.1136/bjo.81.4.283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulenburg WE, Bloom PA. Current problems in the management of ROP. Acta Ophthalmol Scand Suppl 1995;214:14–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen SD, Sundaram V, Wilkinson A et al. Variation in anaesthesia for the laser treatment of retinopathy of prematurity-a survey of ophthalmologists in the UK. Eye (Lond) 2007;21:1033–6. 10.1038/sj.eye.6702499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Sullivan A, O'Connor M, Brosnahan D et al. Sweeten, soother and swaddle for retinopathy of prematurity screening: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2010;95:419–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y, Feng J, Li F et al. Analysis of changes in characteristics of severe retinopathy of prematurity patients after screening guidelines were issued in China. Retina 2015;35:1674–9. 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roohipoor R, Karkhaneh R, Farahani A et al. Retinopathy of prematurity screening criteria in Iran: new screening guidelines. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2016;101:F288–93. 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weaver DT, Murdock TJ. Telemedicine detection of type 1 ROP in a distant neonatal intensive care unit. J AAPOS 2012;16:229–33. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inan UU, Polat O, Inan S et al. Comparison of pain scores between patients undergoing pan retinal photocoagulation using navigated or pattern scan laser systems. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2016;79:15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slevin M, Murphy JF, Daly L et al. Retinopathy of prematurity, stress related responses, the role of nesting. Br J Ophthalmol 1997;81:762–4. 10.1136/bjo.81.9.762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parvaresh MM, Ghasemi Falavarjani K, Modarres M et al. Transscleral diode laser photocoagulation for type 1 prethreshold retinopathy of prematurity. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2013;8:298–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jalali S, Azad R, Trehan HS et al. Technical aspects of laser treatment for acute retinopathy of prematurity under topical anesthesia. Indian J Ophthalmol 2010;58:509–15. 10.4103/0301-4738.71689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato Y, Oshiro M, Takemoto K et al. Multicenter observational study comparing sedation/analgesia protocols for laser photocoagulation treatment of retinopathy of prematurity. J Perinatol 2015;35:965–9. 10.1038/jp.2015.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Örge FH, Lee TJ, Walsh M et al. Comparison of fentanyl and morphine in laser surgery for retinopathy of prematurity. J AAPOS 2013;17:135–9. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirwan C, O'Keefe M, Prendergast M et al. Morphine analgesia as an alternative to general anaesthesia during laser treatment of retinopathy of prematurity. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2007;85:644–7. 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00900.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hummel P, Puchalski M, Creech SD et al. Clinical reliability and validity of the N-PASS: neonatal pain, agitation and sedation scale with prolonged pain. J Perinatol 2008;28:55–60. 10.1038/sj.jp.7211861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stokowski LA. Validation of the N-PASS. Adv Neonatal Care 2008;8:75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garten L, Deindl P, Schmalisch G et al. Parallel assessment of prolonged neonatal distress by empathy-based and item-based scales. Eur J Pain 2010;14:878–81. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munsters J, Wallström L, Agren J et al. Skin conductance measurements as pain assessment in newborn infants born at 22–27 weeks gestational age at different postnatal age. Early Hum Dev 2012;88:21–6. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novitskaya ES, Kostakis V, Broster SC et al. Pain score assessment in babies undergoing laser treatment for retinopathy of prematurity under sub-tenon anaesthesia. Eye (Lond) 2007;27:1405–10. 10.1038/eye.2013.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hummel P, Lawlor-Klean P, Weiss MG. Validity and reliability of the N-PASS assessment tool with acute pain. J Perinatol 2010;30:474–8. 10.1038/jp.2009.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giordano V, Deindl P, Kuttner S et al. The Neonatal Pain, Agitation and Sedation Scale reliably detected oversedation but failed to differentiate between other sedation levels. Acta Paediatr 2014;103:515–21. 10.1111/apa.12770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]