Abstract

Objectives

The use of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) in European obstetric units is unknown. We aimed to describe reported policies and actual use of MgSO4 in women delivering before 32 weeks of gestation by indication.

Methods

We used data from the European Perinatal Intensive Care in Europe (EPICE) population-based cohort study of births before 32 weeks of gestation in 19 regions in 11 European countries. Data were collected from April 2011 to September 2012 from medical records and questionnaires. The study population comprised 720 women with severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP and 3658 without pre-eclampsia delivering from 24 to 31 weeks of gestation in 119 maternity units with 20 or more very preterm deliveries per year.

Results

Among women with severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP, 255 (35.4%) received MgSO4 before delivery. 41% of units reported use of MgSO4 whenever possible for pre-eclampsia and administered MgSO4 more often than units reporting use sometimes. In women without pre-eclampsia, 95 (2.6%) received MgSO4. 9 units (7.6%) reported using MgSO4 for fetal neuroprotection whenever possible. In these units, the median rate of MgSO4 use for deliveries without severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia and HELLP was 14.3%. Only 1 unit reported using MgSO4 as a first-line tocolytic. Among women without pre-eclampsia, MgSO4 use was not higher in women hospitalised before delivery for preterm labour.

Conclusions

Severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP are not treated with MgSO4 as frequently as evidence-based medicine recommends. MgSO4 is seldom used for fetal neuroprotection, and is no longer used for tocolysis. To continuously lower morbidity, greater attention to use of MgSO4 is needed.

Keywords: PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to explore reported policies of use of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) and the actual use in European obstetrical units by indication.

A major strength of the study is the multinational, prospective population-based sample which includes deliveries in all public and private maternity hospitals in 19 regions in 11 European countries covering over 850 000 births annually securing a high degree of generalisability.

Another strength is the low risk of interobserver variability between units due to pre-established definitions of diagnoses and terms and pretested questionnaires in all regions.

Limitations include missing information for validation of severe pre-eclampsia as blood pressures, urine samples and blood chemistry were not collected.

Introduction

Magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) has long been used in obstetric practice. Evidence supports the use of MgSO4 as a first-line treatment for severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia.1 Its previous use as a tocolytic is no longer recommended as it was found to be ineffective in inhibiting preterm birth.2 Currently, it is debated whether MgSO4 can also be used to protect the immature fetal and neonatal brain. Several meta-analyses found that MgSO4, administered prior to preterm birth, decreases risks of cerebral palsy.3–6 However, some have suggested that additional data are needed before accepting MgSO4 as an evidence-based therapy for fetal neuroprotection.7 The biological mechanisms of MgSO4 are unclear. Possible mechanisms include an ability to decrease the levels of proinflammatory cytokines8 9 and to dilate fetal cerebral and umbilical arteries.10 11

National guidelines concerning administration of MgSO4 to prevent eclampsia are available in many European countries,12 and a guideline is also available from the WHO.13 Only a few countries in Europe, however, including Belgium, Ireland and the UK, have guidelines on the use of MgSO4 for neuroprotection.14–16 A Canadian study on the actual use of MgSO4 was recently published,17 but except for a small, retrospective French single-centre study,18 data on use of MgSO4 in Europe are lacking.

We aimed to explore reported policies of use of MgSO4 and the actual use in European obstetrical units by indication in women giving birth before 32 weeks of gestation using data from a large population-based multiregional cohort.

Material and methods

Study design

This study is based on the analysis of data from the European Perinatal Intensive Care in Europe (EPICE) cohort.19 This is a population-based, prospective cohort study of infants born at 22+0 weeks to 31+6 weeks of gestation in 19 regions in 11 countries in Europe (Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and the UK).

Data were collected on all births in each region during varying 12-month periods between April 2011 and September 2012, with the exception of France where the inclusion period lasted 6 months. Clinical data were collected from medical records in 431 obstetric and their associated neonatal units following a standardised protocol, established by a scientific committee and pretested before data collecting began. Data were cross-checked with maternity registers or other external data sources.

In the spring of 2012, a unit questionnaire was also sent by mail or email to department heads of obstetrical and neonatal units caring for infants in the cohort. Units with a neonatal department admitting at least 10 very preterm infants per year were included in this study. The unit questionnaires collected information on the structural characteristics and protocols and policies related to the care of very preterm infants. The questionnaire was pretested outside of the study regions in all countries.

Data and definitions

We used data from the cohort study on maternal, pregnancy and fetal characteristics including maternal age, gestational age, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), sex of the fetus, number of fetuses, parity, in utero transfer, pregnancy complications, use of prenatal corticosteroids (at least one injection), caesarean section (prelabour or after onset of labour), indication for the caesarean section (fetal reasons, maternal reasons or unit policy) and administration of MgSO4 before delivery (including timing of first dose and total dose). Gestational age was defined as the attending obstetrician's best estimate based on last menstrual period, obstetric history or prenatal ultrasound.

Pregnancy complications were pre-eclampsia, HELLP, eclampsia, antepartum haemorrhage (after 20 weeks), admission to hospital for preterm labour after 20 weeks and infection if this was an indication for delivery. The definition of these conditions was established prior to data collection. Pre-eclampsia was a specific item collected in the EPICE study and was defined as proteinuria and systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg occurring after gestational week 20+0 in a woman who was normotensive prior to becoming pregnant. Proteinuria was defined as ≥300 mg/L protein in a random specimen or an excretion of 300 mg/24 hours. Hypertension had to be confirmed by two separate measurements. HELLP syndrome was defined as a cluster of laboratory abnormalities including serum lactic dehydrogenase >600 U/L, serum aspartate aminotransferase or serum alanine aminotransferase >70 U/L and platelet count <100 000/mm3. Eclampsia was defined as the onset of seizures in a woman with pre-eclampsia.

From the obstetrical unit questionnaire, we used information on reported treatment policies and practices for treatment of preterm labour and for use of MgSO4. The units were asked if “in your unit, magnesium sulfate is used to treat pre-eclampsia or for fetal neuroprotection”. Possible responses were ‘whenever possible’, ‘sometimes’ or ‘never’. Information on the first-line tocolytics used in the unit was also collected.

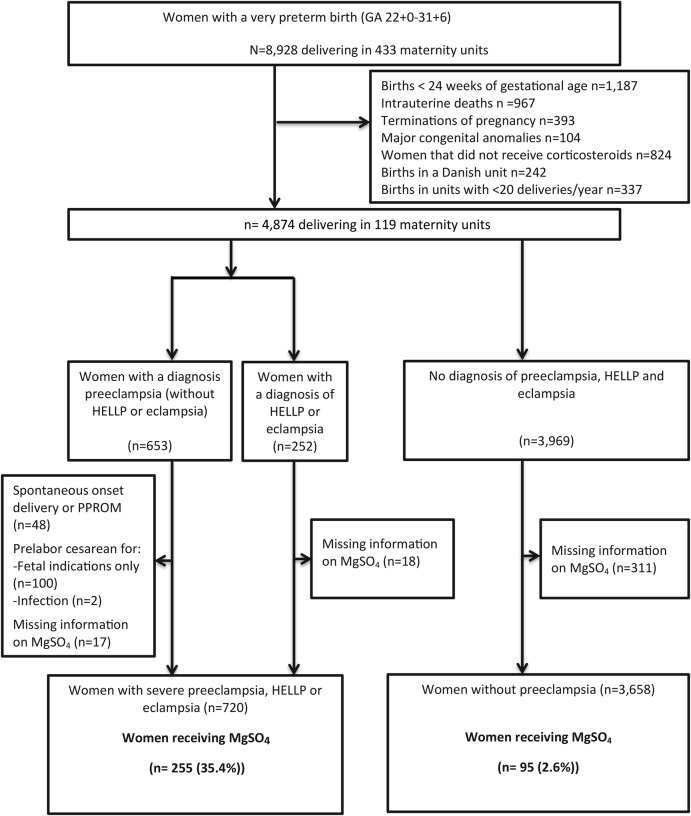

Study population

We defined two populations in order to assess use of MgSO4 for severe pre-eclampsia or for fetal neuroprotection (see figure 1 for the study flow chart). For both populations, we excluded women giving birth before 24+0 weeks of gestation due to expected differences in levels of treatment for this extremely low gestational age. We also excluded women who had not received prenatal steroids. We hypothesised that if there had been time to administer steroids, MgSO4 could also have been given. We also excluded all Danish units in the sample as they were participating in a national, randomised, double-blinded controlled trial of the use of MgSO4 for fetal neuroprotection in preterm birth during the study period. Finally, units with fewer than 20 very preterm deliveries per year were excluded in order to focus on units which regularly cared for high-risk pregnancies and to obtain a sufficient sample size to assess use at the unit level.

Figure 1.

Flow chart—definition of study populations and use of MgSO4. MgSO4, magnesium sulfate; PPROM, preterm prelabour rupture of membranes.

The first population included women who had severe pre-eclampsia. We could not use the commonly accepted criteria20 for severe pre-eclampsia as information on blood pressures, urine samples, blood chemistry and symptoms was not collected. Instead, we defined severe pre-eclampsia as a diagnosis of eclampsia or HELLP, regardless of mode of delivery or as a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia combined with a prelabour caesarean section performed for maternal indications before 32 weeks of gestation. We excluded women who had prelabour caesarean sections for fetal indications (eg, IUGR, fetal distress), due to intrauterine infection or in association with preterm prelabour rupture of membranes (PPROM).

The second population was constituted of women without a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP; we surmised that in this group, MgSO4 would be given for indications unrelated to pre-eclampsia, that is, fetal neuroprotection or tocolysis.

Analysis strategy

We first described the characteristics of the two populations included in our study and then described units' reported policies for use of MgSO4 as well as the actual use in these units by indication (the per cent of women in each relevant population receiving MgSO4 in each unit). We then explored maternal, pregnancy and neonatal factors as well as unit policy associated with MgSO4 use in the cohort, using univariable and multivariable analyses. For multivariable analyses, we used mixed-effect logistic models to take into consideration the hierarchical structure of our data (correlation between observations within regions).

In sensitivity analyses, we removed all pre-eclamptic pregnancies associated with antenatally detected IUGR to remove situations in which the indicated delivery may have been for fetal reasons. We also compared our final models including patient and unit variables with a model including only patient level factors. Finally, we assessed the impact of excluding units with fewer than 20 very preterm births from our study population by comparing policies in included and excluded units and the women delivering in these units.

Analyses were carried out using STATA version 13.1 SE (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

In the EPICE cohort, 4874 women from 119 different units were considered for the study after exclusions; the final analysis included 4378 women after further exclusions of cases with pre-eclampsia associated with spontanous onset of labour, PPROM or cesasrean section for fetal reasons, as well missing data on MgSO4 (see figure 1 for the study flow chart). Of these women, 720 were classified as having severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP; 3658 were classified as not having these conditions. Among women with severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP, 35.4% received MgSO4 before delivery (figure 1). This proportion was 33.7% for pre-eclamptic women without either a diagnosis of HELLP or eclampsia (data not shown). Among women without pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP, only 2.6% received MgSO4 before delivery.

Table 1 describes the study populations. As expected, the maternal and pregnancy characteristics of the pre-eclamptic and non-pre-eclamptic women differed. Women with severe pre-eclampsia were slightly more likely to have both lower and higher ages and were more often primiparous. They also had lower rates of deliveries at extremely preterm gestations (<26 weeks of gestation). The proportion of female infants was higher in the pre-eclamptic population than in the non-pre-eclamptic population (54.2% and 45.2%, respectively). The proportion of multiple pregnancies was lower in the pre-eclamptic population than in the non-pre-eclamptic population. IUGR was diagnosed before birth in 41.3% of the cases in the pre-eclamptic population, and in 12.8% of the cases in the non-pre-eclamptic population. The number of in utero transfers in the two populations was similar, but the rates of caesarean sections were much higher in the pre-eclamptic population (99.2% and 60.4%, respectively).

Table 1.

Description of women delivering between 24+0 and 31+6 weeks of gestation with severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP (population 1) and without a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia, HELLP or eclampsia (population 2)

| Women with severe pre-eclampsia* (n=720) | Women without pre-eclampsia, HELLP or eclampsia (n=3658) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Maternal age (years) | |||

| <25 | 138 (19.3) | 631 (17.3) | 0.037 |

| 25–34 | 364 (50.8) | 2044 (56.0) | |

| ≥35 | 214 (29.9) | 972 (26.7) | |

| Parity | |||

| Primiparous | 474 (66.2) | 1944 (53.5) | <0.001 |

| Multiparous | 242 (33.8) | 1690 (46.5) | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | |||

| 24+0–25+6 | 48 (6.7) | 453 (12.4) | <0.001 |

| 26+0–28+6 | 216 (30.0) | 1148 (31.4) | |

| 29+0–31+6 | 456 (63.3) | 2057 (56.2) | |

| Diagnosis of IUGR | |||

| No | 421 (58.7) | 3173 (87.2) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 296 (41.3) | 466 (12.8) | |

| Sex of baby | |||

| Male | 329 (45.8) | 2006 (54.8) | <0.001 |

| Female | 390 (54.2) | 1652 (45.2) | |

| Type of pregnancy | |||

| Singleton | 682 (94.7) | 2846 (77.8) | <0.001 |

| Multiple | 38 (5.3) | 811 (22.2) | |

| Pregnancy complications | |||

| Eclampsia | 51 (7.2) | – | |

| HELLP | 198 (27.8) | – | |

| Antepartum haemorrhage | 26 (3.7) | 865 (23.9) | <0.001 |

| Admission for preterm labour | 35 (4.9) | 1974 (54.4) | <0.001 |

| PPROM | – | 1283 (35.2) | <0.001 |

| Infection as indication for delivery | – | 421 (12.2) | <0.001 |

| In utero transfer | 249 (35.0) | 1242 (34.2) | 0.668 |

| Mode of delivery | |||

| Vaginal | 6 (0.8) | 1441 (39.6) | <0.001 |

| Caesarean | 709 (99.2) | 2195 (60.4) | |

*Defined as a diagnosis of eclampsia or HELLP, regardless of mode of delivery or a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia and a prelabour caesarean section.

HELLP, Haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; PPROM, preterm prelabour rupture of membranes.

Table 2 shows the policies as well as the actual use of MgSO4 in European obstetrical units. For severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP, most units reported using MgSO4 whenever possible (41.2%) or sometimes (41.2%). Practices reflected policies. Units reporting use of MgSO4 whenever possible had higher median rates of MgSO4 use than units reporting a policy of MgSO4 use sometimes (25.0% vs 12.5%). However, many units did not use MgSO4 over the study period (as seen by the IQR) despite a reported policy treatment. Only 5 of 119 units said that they did not use MgSO4 for severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP and this was consistent with observed rates of use. Ten units did not respond to the question of MgSO4 treatment for severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP and 6 units did not return the questionnaire; in these 16 units, MgSO4 was used over the study period.

Table 2.

Policies and observed use of MgSO4 for severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP, for fetal neuroprotection or for tocolysis in women delivering very preterm (<32 weeks of gestation) in European obstetrical units

| Maternity units (n=119) | Women with severe pre-eclampsia (n=720) | Percentage of pre-eclamptic women receiving MgSO4 in units | Women without pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP (n=3658) | Percentage of non-pre-eclamptic women receiving MgSO4 in units | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | Median (IQR) | n (%) | Median (IQR) | |

| Unit policy for pre-eclampsia | |||||

| MgSO4 whenever possible | 49 (41.2) | 296 (41.1) | 25.0 (0–60.0) | 1623 (44.4) | 0 (0–3.0) |

| MgSO4 sometimes | 49 (41.2) | 339 (47.1) | 12.5 (0–42.9) | 1554 (42.5) | 0 (0–0) |

| Never | 5 (4.2) | 32 (4.4) | 0 (0–0) | 145 (4.0) | 0 (0–0) |

| No response* | 16 (13.4) | 53 (7.4) | 34.8 (0–60.0) | 336 (9.2) | 0 (0–1.4) |

| Unit policy for neuroprotection | |||||

| MgSO4 whenever possible | 9 (7.6) | 69 (9.6) | 33.3 (16.7–72.7) | 260 (7.1) | 14.3 (0–37.8) |

| MgSO4 sometimes | 19 (16.0) | 118 (16.4) | 20.0 (0–60.0) | 749 (20.5) | 0 (0–4.8) |

| Never | 70 (58.8) | 454 (63.1) | 11.8 (0–50.0) | 2173 (59.4) | 0 (0–0) |

| No response† | 21 (17.6) | 79 (11.0) | 36.4 (0–60.0) | 476 (13.0) | 0 (0–1.9) |

| MgSO4 is a first-line tocolytic | 1 (0.88) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 8 (0.2) | 0.0 |

*Includes 10 units that returned the questionnaire, but did not respond to this question and six units that did not return the unit questionnaire.

†Includes 15 units that returned the questionnaire, but did not respond to this question and six units that did not return the unit questionnaire.

MgSO4, magnesium sulfate.

For fetal neuroprotection, very few units reported using MgSO4 whenever possible (7.6%); a further 16.0% reported a policy of MgSO4 treatment sometimes. Observed rates varied by unit responses, but rates were low even in units that had a policy of MgSO4 treatment ‘whenever possible’; the median rate of MgSO4 treatment of women in the non-pre-eclamptic population was 14.3%.

Only 1 unit (<1%) with a small number of women in the study population reported using MgSO4 as a first-line tocolytic.

Table 3 provides data on policies and observed use of MgSO4 when regions are grouped by country. There was a large variability in both unit policies and actual use among women (online supplementary table S1 provides information on the study population and the exclusion criteria as applied to each country). Some countries appeared to use MgSO4 routinely for severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP, whereas use was much lower in others (France, Italy and Portugal). Use in the non-pre-eclamptic population was low in all study regions, and in 6 of 10 countries, fewer than 3% of women in the non-pre-eclamptic population were treated with MgSO4.

Table 3.

Policies and observed use of MgSO4 treatment for very preterm birth (<32 weeks of gestation) by indication and country

| Country (region) | Units | Whenever possible for pre-eclampsia | Women with severe pre-eclampsia | Women receiving MgSO4 | Whenever possible or sometimes for neuroprotection | Women without pre-eclampsia, HELLP or eclampsia | Women receiving MgSO4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percentage of units | n | Per cent | Percentage of units | n | Per cent | |

| Belgium (Flanders) | 9 | 33.3 | 70 | 67.1 | 11.1 | 367 | 2.7 |

| Estonia (whole country) | 3 | 33.3 | 19 | 21.1 | 0.0 | 93 | 3.2 |

| France (Northern region, Burgundy, Ile-de-France) | 21 | 0.0 | 155 | 18.1 | 23.8 | 550 | 2.0 |

| Germany (Hesse, Saarland) | 13 | 53.9 | 45 | 40.0 | 30.8 | 228 | 6.6 |

| Italy (Lazio, Emilia-Romania, Marche) | 20 | 50.0 | 107 | 15.9 | 25.0 | 620 | 1.1 |

| Netherlands (East-Central) | 2 | 50.0 | 45 | 91.1 | 50.0 | 206 | 0.5 |

| Poland (Wielkopolska) | 2 | 100.0 | 5 | 60.0 | 100.0 | 114 | 12.3 |

| Portugal (Northern and Lisbon) | 13 | 76.9 | 88 | 9.1 | 38.5 | 399 | 5.5 |

| Sweden (Stockholm) | 4 | 0.0 | 40 | 40.0 | 0.0 | 147 | 0.0 |

| UK (Northern, East Midlands, Yorkshire & Humber) | 32 | 46.9 | 146 | 50.0 | 15.6 | 934 | 1.3 |

Women with a non-anomalous live birth who received prenatal corticosteroids and delivered in a maternity unit with more than 20 very preterm deliveries annually (see online supplementary table S1 for exclusions by country).

MgSO4, magnesium sulfate.

Sample sizes after each exclusion criteria in each region (corresponds to totals in flow chart, Figure 1)

bmjopen-2016-013952supp_table1.pdf (203.9KB, pdf)

Table 4 shows the factors associated with greater use of MgSO4 in the pre-eclamptic and the non-pre-eclamptic population. For women in the pre-eclamptic population, a gestational age between 26+0–28+6 weeks and/or having a diagnosis of eclampsia was associated with more frequent use of MgSO4. In the same population, having a diagnosis of IUGR or HELLP and admission for preterm labour were associated with less frequent use of MgSO4. While the proportion of women receiving MgSO4 was higher in units reporting use whenever possible, the difference was not significant in adjusted analyses. In the non-pre-eclamptic population, gestational ages from 24+0–25+6 to 26+0–28+6 were associated with more frequent use of MgSO4, whereas lack of a unit policy on the use of MgSO4 was associated with less frequent use. In the non-pre-eclamptic group, being hospitalised for preterm labour was not associated with use of MgSO4.

Table 4.

Maternal and unit factors associated with MgSO4 treatment of women with severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP or fetal neuroprotection in women without pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP

| Women with severe pre-eclampsia* (255/720) |

Women without pre-eclampsia, HELLP or eclampsia (95/3658) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receiving MgSO4 | n/N | Per cent | aOR | 95% CI | n/N | Per cent | aOR | 95% CI |

| Maternal age (years) | ||||||||

| <25 | 58/158 | 42.0 | 1.32 | (0.72 to 2.41) | 24/631 | 3.8 | 1.68 | (0.84 to 3.35) |

| 25–34 | 131/364 | 36.0 | 0.89 | (0.56 to 1.42) | 47/2044 | 2.3 | 0.86 | (0.48 to 1.55) |

| ≥35 | 64/214 | 29.9 | Ref. | 24/972 | 2.5 | Ref. | ||

| Parity | ||||||||

| Primiparous | 77/242 | 31.8 | 1.07 | (0.7 to 1.65) | 44/1690 | 2.6 | 0.84 | (0.51 to 1.36) |

| Multiparous | 177/474 | 37.3 | Ref. | 50/1944 | 2.6 | Ref. | ||

| Gestational age (weeks) | ||||||||

| 24+0–25+6 | 18/48 | 37.5 | 1.71 | (0.78 to 3.74) | 18/453 | 4.0 | 2.31 | (1.13 to 4.74) |

| 26+0–28+6 | 86/216 | 39.8 | 1.64 | (1.07 to 2.51) | 36/1148 | 3.1 | 1.71 | (1.02 to 2.86) |

| 29+0–31+6 | 151/456 | 33.1 | Ref. | 41/2057 | 2.0 | Ref. | ||

| Diagnosis of IUGR | ||||||||

| No | 161/421 | 38.2 | Ref. | 79/3173 | 2.5 | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 92/296 | 31.1 | 0.65 | (0.43 to 0.99) | 14/466 | 3.0 | 1.12 | (0.54 to 2.33) |

| Sex of baby | ||||||||

| Male | 112/329 | 34.0 | 0.89 | (0.6 to 1.32) | 54/2006 | 2.7 | 0.90 | (0.55 to 1.45) |

| Female | 143/390 | 36.7 | Ref. | 41/1652 | 2.5 | Ref. | ||

| Type of pregnancy | ||||||||

| Singleton | 13/38 | 34.2 | 1.19 | (0.47 to 3.03) | 12/811 | 1.5 | 1.80 | (0.92 to 3.54) |

| Multiple | 242/682 | 35.5 | Ref. | 83/2846 | 2.9 | Ref. | ||

| Pregnancy complications | ||||||||

| Eclampsia | 23/51 | 45.1 | 2.21 | (1.03 to 4.71) | – | – | – | – |

| HELLP | 72/198 | 36.4 | 0.60 | (0.37 to 0.97) | – | – | – | – |

| Antepartum haemorrhage | 7/26 | 26.9 | 0.49 | (0.15 to 1.56) | 23/865 | 2.7 | 0.78 | (0.44 to 1.41) |

| Admission for preterm labour | 4/35 | 11.4 | 0.18 | (0.04 to 0.7) | 51/1974 | 2.6 | 0.67 | (0.39 to 1.15) |

| PPROM | 1/5 | – | – | – | 29/1283 | 2.3 | 0.57 | (0.32 to 1.01) |

| Infection as indication for delivery | 1/1 | 100 | – | – | 14/421 | 3.3 | 1.30 | (0.64 to 2.64) |

| In utero transfer | 95/295 | 38.2 | 1.44 | (0.92 to 2.27) | 34/1242 | 2.7 | 0.78 | (0.45 to 1.36) |

| Unit polices of MgSO4 use | ||||||||

| for pre-eclampsia | ||||||||

| Whenever possible | 125/296 | 42.2 | Ref. | – | – | – | – | |

| Sometimes | 106/339 | 31.3 | 0.73 | (0.43 to 1.25) | – | – | – | – |

| Never | 0/32 | 0.0 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| No response | 29/53 | 45.3 | 0.70 | (0.34 to 1.47) | – | – | – | – |

| for neuroprotection | ||||||||

| Whenever possible | – | – | – | – | 47/260 | 18.1 | Ref. | |

| Sometimes | – | – | – | – | 24/749 | 3.2 | 0.08 | (0.03 to 0.19) |

| Never | – | – | – | – | 14/2173 | 0.6 | 0.02 | (0.01 to 0.04) |

| No response | – | – | – | – | 10/476 | 2.1 | 0.08 | (0.03 to 0.24) |

*Defined as a diagnosis of eclampsia or HELLP, regardless of mode of delivery, or a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia and a prelabour caesarean section before 32 weeks of gestation.

HELLP, Haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; PPROM, preterm prelabour rupture of membranes.

MgSO4, magnesium sulfate.

Sensitivity analyses showed similar results in the pre-eclamptic group when cases with antenatal detection of IUGR were removed (see online supplementary table S2) and individual patient level characteristics had a similar impact in models without unit policy variables (see online supplementary table S3). Policies and practices in the 10 units in the unit study that were excluded because they had fewer than 20 very preterm births per year were not significantly different from units included in our study (see online supplementary table S4).

Maternal and unit factors associated with MgSO4 treatment of women with severe preeclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP after exclusion of IUGR cases

bmjopen-2016-013952supp_table2.pdf (306.1KB, pdf)

Maternal and unit factors associated with MgSO4 treatment after exclusion of unit policy variables

bmjopen-2016-013952supp_table3.pdf (311.8KB, pdf)

Comparison of Excluded and Included Units

bmjopen-2016-013952supp_table4.pdf (315.9KB, pdf)

Discussion

Main findings

This large, population-based observational study yielded three main findings on the use of MgSO4 for very preterm birth in European obstetric units. First, we found that severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia and HELLP were treated with MgSO4, but not as frequently as evidence-based medicine recommends. Second, we found that MgSO4 was seldom used for fetal neuroprotection, and third, that MgSO4 is no longer used for tocolysis.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the study are its multinational, prospective population-based sample which includes deliveries in all public and private maternity hospitals in 19 regions in 11 European countries covering over 850 000 births annually. Also, both tertiary and non-tertiary centres were included. This ensures high generalisability to a wide range of settings. The risk of interobserver variability between units was minimised by using pre-established definitions of diagnoses and terms and pretesting questionnaires in all regions.

Limitations include some missing data on administration of MgSO4. We also did not have indications for MgSO4 use and therefore created subgroups of patients likely to receive MgSO4 for severe pre-eclampsia or neuroprotection. In the group of women without pre-eclampsia, we assumed that MgSO4 was given either for neuroprotection or tocolysis. For women with pre-eclampsia, we could not validate the diagnosis of severe pre-eclampsia as blood pressures, urine samples and blood chemistry were not collected, but we assumed that a pre-eclamptic condition resulting in a prelabour caesarean section on maternal indication before 32 weeks of gestation was most likely to be severe. While we excluded prelabour caesareans for fetal indications and intrauterine infection in order to remove women unlikely to have severe pre-eclampsia, some caesareans could have been carried out primarily for IUGR, even if maternal reasons were also indicated. To address this issue, we carried out a sensitivity analysis removing these cases and our results were similar.

Interpretation

Despite global consensus about its effectiveness and safety for preventing eclampsia, only 41.2% of the units reported use of MgSO4 whenever possible in case of pre-eclampsia and MgSO4 was used in only 35.4% of women with severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP. This might be a slight underestimation as only antenatal use was registered. A Canadian study from 2015 found a discrepancy between national and local guidelines.17 In the Canadian study, 79% of women with severe pre-eclampsia received MgSO4. However, this estimate was based on only 174 patients and suffered from variation in the definition of severe pre-eclampsia. We found wide country variation in use of MgSO4, with lower use in France, Italy and Portugal. While studies on practices of MgSO4 use in European countries are lacking, several studies have examined MgSO4 administration for women with eclampsia and have documented low use for prevention in these cases.21–23

Our results are also in line with evidence from Mexico and Thailand showing that MgSO4 is underused in women with pre-eclampsia and eclampsia.24 Multiple barriers have been identified in low-income and middle-income countries, including failure in registration, distribution, unmet training needs, suboptimal implementation of guidelines and reluctance of staff to use MgSO4 because of required intensive patient monitoring.24–27 High-income countries have fewer barriers for accessing antenatal care, early diagnosis of pre-eclampsia and follow-up during and after delivery. However, the same challenges may exist with respect to medical staff concerns about the handling of MgSO4 and risks of serious maternal side effects, such as respiratory arrest, arrhythmia and pulmonary oedema.

The evidence that MgSO4 is an ineffective tocolytic appears to be integrated into clinical practice. Only 1 unit reported using MgSO4 as a first-line tocolytic and use was not higher among women admitted to hospital for preterm labour in the non-pre-eclamptic population.

Despite the Cochrane meta-analysis published in 2009,5 an ACOG guideline from March 201028 and an RCOG scientific impact statement in August 201129 all recommending use of MgSO4 for fetal neuroprotection, this study reveals an almost non-existing use of MgSO4 for fetal neuroprotection in Europe in the study period. The reluctance to adopt this practice may be due to the trial sequential analysis from 2011 concluding that randomisation of an additional 400 women was needed to obtain sufficient evidence to introduce MgSO4 as a standard treatment for neuroprotection.7 Other possible explanations are the fairly high number-needed-to-treat of 56 (95% CI 26 to 187) to prevent cases of cerebral palsy in deliveries before 34 weeks of gestation,30 lack of clinical guidelines, and concerns for adverse drug effects necessitating intense monitoring when administering MgSO4. Finally, some obstetricians might be waiting for the results of an ongoing randomised controlled trial from Denmark expected in 2018.31

Since our study, new guidelines for neuroprotection were issued in two of the countries participating in EPICE, the UK in November 201514 and Belgium in July 2014.16 Guidelines were also issued in Ireland, which is not part of EPICE.15 In both guidelines, MgSO4 is highly recommended for neuroprotection to women presenting with imminent preterm birth before 32 weeks of gestation. It is therefore possible that practices have evolved in these countries. To the best of our knowledge, however, there have been no new guidelines in other regions and no new evidence from randomised trials of the effectiveness of MgSO4 has been published.

Conclusion

Evidence-based use of MgSO4 is applied less than expected in European obstetric units. Future research should focus on how to promote evidence-based use of MgSO4 for severe pre-eclampsia. Options include an increased focus on the existing guidelines, instituting audits and simulation training in the maternity ward to familiarise medical staff with the handling of MgSO4. Our results showing low use of MgSO4 in non-pre-eclamptic women suggest that obstetricians are not convinced by available evidence on MgSO4’s neuroprotective effect. Our results provide a useful baseline for evaluating practice changes as more evidence becomes available and more national societies develop guidelines for use of MgSO4 for neuroprotection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the participation of the Departments of Obstetrics and Neonatology from hospitals in the EPICE regions: Belgium (Flanders): ASZ Campus Geraardsbergen, Geraardsbergen; AZ Sint Maarten, Campus Zwartzustervest, Mechelen; AZ Sint Lucas, Assebroek; AZ Heilige Familie, Rumst-Reet; Sint Jozefskliniek, Izegem; AZ Sint Jozef, Malle; Sint Augustinus—MISA, Wilrijk; Onze Lieve Vrouwziekenhuis Campus Asse, Asse; AZ Diest, Diest; AZ Zeno Campus Knokke—Heist, Knokke-Heist; AZ Groeninge, Kortrijk; Sint Jozefkliniek—Campus Bornem, Bornem; Sint Vincentiusziekenhuis, Deinze; Maria Middelares, Gent; AZ Oudenaarde, Oudenaarde; AZ Glorieux, Ronse; AZ Delta Campus Menen, Menen; AZ Sint Elisabeth, Zottegem; ZOL—Campus Sint Jan, Genk; Jessa Ziekenhuis Campus Virga Jesse, Hasselt; Sint Franciskusziekenhuis, Heusden-Zolder; Maria Ziekenhuis Noord-Limburg, Overpelt; Sint Trudoziekenhuis, Sint-Truiden; AZ Damiaan, Oostende; AZ Sint Lucas, Gent; AZ Sint Blasius, Dendermonde; AZ Delta Campus Wilgenstraat, Roeselare; UZ Brussel, Brussel; ZNA Jan Palfijn, Merksem; Sint Andriesziekenhuis, Tielt; ZNA Middelheim, Antwerpen; Imeldaziekenhuis, Bonheiden; AZ Sint Maarten—Campus Duffel, Duffel; AZ KLINA, Brasschaat; AZ Jan Portaels, Vilvoorde; Universitair Ziekenhuis Antwerpen, Edegem; UZ Leuven Campus Gasthuisberg, Leuven; UZ Gent, Gent; Sint Vincentiusziekenhuis—Campus Sint Jozef, Mortsel; AZ Alma, Eeklo; AZ Turnhout, Turnhout; Heilig Hartziekenhuis, Mol; AZ Sint Jan Campus Henri Serruys, Oostende; Ziekenhuis Maas & Kempen, Bree; Sint Vincentius Ziekenhuis, Antwerpen; AZ Vesalius—Campus Sint Jacobus, Tongeren; ASZ—Campus Aalst, Aalst; Onze Lieve Vrouwziekenhuis—Campus Aalst, Aalst; AZ Delta Campus Stedelijk Ziekenhuis, Roeselare; AZ Sint Rembert, Torhout; AZ Monica—Campus Deurne, Deurne; AZ Lokeren, Lokeren; Jan Ypermanziekenhuis, Ieper; AZ Sint Elisabeth, Herentals; AZ Sint Jan, Brugge; AZ Jan Palfijn, Gent; AZ Sint Augustinus Veurne, Veurne; RZ Sint Maria, Halle; Heilig Hart Ziekenhuis, Leuven; AZ Nikolaas—Campus SM, Sint-Niklaas; Onze Lieve Vrouw van Lourdes Ziekenhuis Waregem vzw, Waregem; ACZA Ziekenhuis—Campus Sint Erasmus, Borgerhout; Heilig Hart, Lier; AZ Sint Dimpna, Geel; Heilig Hart, Tienen. Estonia: Tallinn Children's Hospital, Unit of Newborns and Infants; Tallinna Children's Hospital, Paediatric Intensive Care Unit; Tartu University Hospital, Neonatal Unit; Tartu University Hospital, Paediatric Intensive Care Unit; East-Tallinn Central Hospital, Neonatal Unit; West-Tallinn Central Hospital, Neonatal Unit. Denmark (Eastern Region): University Hospital of Copenhagen (Rigshospitalet); Hvidovre University Hospital; Herlev University Hospital; Hilleroed University Hospital; Roskilde University Hospital; Holbaek University Hospital; Naestved University Hospital; University Hospital of Southern Denmark. France (Burgundy): CH d'Autun, Autun; CH Auxerre, Auxerre; CH de Beaune, Beaune; CH William Morey, Chalon Sur Saone; Clinique de Cosne-Sur-Loire, Cosne-Sur-Loire; CH de Decize, Decize; CHU Le Bocage—Hôpital D'enfants, Dijon; Clinique Sainte-Marthe, Dijon; Site Hospitalier Foch, Le Creusot; CH Les Chanaux, Macon; CH de Nevers, Nevers; CH Les Charmes, Paray Le Monial; CH de Semur-En-Auxois, Semur En Auxois; CH de Sens, Sens; France (Ile-de-France): Hôpital Prive D'Antony, Antony; CH Victor Dupouy, Argenteuil; CH Arpajon, Arpajon; Hôpital Prive D'Athis-Mons, Athis-Mons; Hôpital Européen La Roseraie, Aubervilliers; CHI Robert Ballanger, Aulnay Sous-Bois; CH Intercommunal Des Portes de L'Oise, Beaumont Sur Oise; CHU Jean Verdier, Bondy; Clinique Ambroise Paré, Bourg-La-Reine; Hôpital Privé de Marne Chantereine, Brou Sur Chantereine; Hôpital Prive de Marne La Vallée, Bry Sur Marne; Hôpital Saint-Camille, Bry Sur Marne; Clinique de Champigny-Hôpital Paul D'Egine, Champigny Sur Marne; Hôpital Antoine Béclère, Clamart; Hôpital Beaujon, Clichy; CH Louis Mourier, Colombes; Clinique Du Parisis, Cormeilles-En-Parisis; CH René Arbeltier, Coulommiers; CHI Créteil, Créteil; Clinique Claude Bernard, Ermont; CH Sud Essonne, Etampes—Dourdan; CH Louise Michel, Evry; Clinique de L'Essonne Evry, Evry; CMO D'Evry, Evry; Polyclinique de La Forêt, Fontainebleau; CH Fontainebleau, Fontainebleau; CH de Gonesse, Gonesse; Clinique Lambert, La Garenne-Colombes; CHG de Marne La Vallée, Lagny; Hôpital Prive de Seine-Saint-Denis, Le Blanc Mesnil; CH de Versailles-André Mignot, Le Chesnay; Hôpital Prive de Parly 2 Le Chesnay, Le Chesnay; CHU Kremlin Bicêtre, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre; Maternité Des Lilas, Les Lilas; Institut Hospitalier Franco-Britannique, Levallois Perret; Clinique Conti, L'Isle-Adam; Polyclinique Vauban, Livry Gargan; Clinique de L'Yvette, Longjumeau; CH de Longjumeau, Longjumeau; CH Mantes La Jolie, Mantes La Jolie; Hôpital Prive Jacques Cartier, Massy; CH de Meaux, Meaux; CH Marc Jacquet, Melun; Polyclinique Saint Jean, Melun; Clinique de Meudon La Foret, Meudon La Foret; CH Intercommunal de Meulan-Les Mureaux, Meulan-En-Yvelines; CH de Montereau, Montereau; CHI Le Raincy-Montfermeil, Montfermeil; Groupe Hospitalier Eaubonne-Montmorency, Montmorency; CHI André Grégoire, Montreuil; Hôpital Max Fourestier, Nanterre; CH Neuilly Courbevoie, Neuilly Sur Seine; Hôpital Américain, Neuilly Sur Seine; Clinique Sainte-Isabelle, Neuilly-Sur-Seine; Hôpital Prive Armand Brillard, Nogent Sur Marne; CH D'Orsay, Orsay; Clinique de La Muette, Paris; Clinique Jeanne D'arc, Paris; Clinique Leonard de Vinci, Paris; Clinique Sainte Thérèse, Paris; Clinique Saint-Louis, Paris; GH Armand Trousseau—La Roche-Guyon, Paris; GH Diaconesses Croix St Simon, Paris; GH Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris; GH Saint Joseph / Notre Dame de Bon-Secours, Paris; GIH Bichat/ Claude Bernard, Paris; Hôpital Cochin-Port Royal, Paris; Hôpital Lariboisière, Paris; Hôpital Les Bluets, Paris; Hôpital Necker, Paris; Hôpital Robert Debré, Paris; Hôpital Saint-Antoine, Paris; Hôpital Tenon, Paris; Institut de Puériculture Et de Périnatalogie, Paris; Institut Mutualiste Montsouris, Paris; Maternité Sainte-Félicité, Paris; CHI Poissy/Saint-Germain-En-Laye, Poissy; CH René Dubos, Pontoise; Centre Hospitalier Léon Binet, Provins; Hôpital Prive Claude Galien, Quincy-Sous-Sénart; CH de Rambouillet, Rambouillet; Clinique Les Martinets, Rueil-Malmaison; CH Des Quatre Villes, Saint Cloud; CH de Saint Denis, Saint Denis; Hôpital Esquirol St Maurice, Saint Maurice; Clinique Saint Germain, Saint-Germain-En-Laye; Hôpital Prive Nord Parisien, Sarcelles; CH Des Quatre Villes, Sèvres; Hôpital Militaire Begin, St Mande; Clinique Gaston Métivet, St Maur Des Fosses; Clinique de L'Estrées, Stains; Hôpital Foch, Suresnes; Clinique de Tournan, Tournan-En-Brie; Hôpital Prive de L'Ouest Parisien, Trappes; Clinique Du Vert-Galant, Tremblay En France; Hôpital Prive de Versailles- Franciscaines, Versailles; CH Intercommunal, Villeneuve Saint Georges; Clinique Les Noriets, Vitry Sur Seine; France (Northern Region): CH D'Armentières, Armentières; CH D'Arras, Arras; Clinique Bon-Secours, Arras; CH de Béthune, Béthune; Clinique Anne D'Artois, Béthune; CH de Boulogne-Sur-Mer, Boulogne Sur Mer; CH de Calais, Calais; CH de Cambrai, Cambrai; Polyclinique Sainte-Marie, Cambrai; CH de Denain, Denain; Polyclinique de La Clarence, Divion; CH de Douai, Douai; Polyclinique Villette, Dunkerque; CH de Fourmies, Fourmies; GCS Flandre Maritime, Grande Synthe; CH D'hazebrouck, Hazebrouck; CH de La Région de St Omer, Helfaut; Clinique Saint-Amé, Lambres-Les-Douai; CH du Cateau, Le Cateau Cambrésis; CH de Lens, Lens; Polyclinique de Riaumont de Lievin, Lievin; GHI CL St-Vincent de Paul, Lille; Hôpital Jeanne de Flandre, Lille; Pavillon Du Bois, Lille; CH Sambre-Avesnois, Maubeuge; Polyclinique Du Val de Sambre, Maubeuge; CHAM Site Principal, Rang Du Fliers; Maternité Paul Gellé, Roubaix; CH de Seclin, Seclin; Centre Médical Chirurgical Obstétrical Côte d'Opale, St Martin/Boulogne; Clinique Maternité du Parc, St Saulve; Clinique Du Val de Lys, Tourcoing; Hôpital Guy Chatiliez, Tourcoing; CH de Valenciennes, Valenciennes; Nouvelle Clinique Villeneuve D’ Ascq, Villeneuve d'Ascq. Germany (Hesse and Saarland): Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin & Klinik für Frauenheilkunde und Geburtshilfe, Klinikum Bad Hersfeld, Bad Hersfeld; Neonatologie, Darmstaedter Kinderkliniken & Frauenklinik, Klinikum Darmstadt, Darmstadt; Klinik für Neonatologie & Frauenklinik, Buergerhospital, Frankfurt; Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin & Klinik für Gynaekologie und Geburtshilfe, Klinikum Frankfurt Hoechst, Frankfurt; Zentrum für Kinderheilkunde & Klinik fuer Frauenheilkunde und Geburtshilfe, Universitaetsklinikum Frankfurt, Frankfurt; Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin & Frauenklinik, Klinikum Fulda, Fulda; Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin & Frauenklinik, Main-Kinzig-Kliniken, Gelnhausen; Allgemeine Paediatrie und Neonatologie & Zentrum für Frauenheilkunde und Geburtshilfe, Universitaetsklinikum Giessen, Giessen; Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin & Klinik für Gynaekologie und Geburtshilfe, Klinikum Hanau, Hanau; Kinderklinik & Klinik für Frauenheilkunde und Geburtshilfe, Klinikum Kassel, Kassel; Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin & Klinik für Frauenheilkunde und Geburtshilfe, Universitaetsklinikum Marburg, Marburg; Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin & Klinik fuer Gynaekologie und Geburtshilfe, Sana Klinikum Offenbach, Offenbach; Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin & Frauenklinik, GPR Klinikum Ruesselsheim, Ruesselsheim; Abteilung Kinder und Jugendliche & Abteilung Geburtshilfe, Dr. Horst Schmidt Kliniken, Wiesbaden; Kinderklinik & Klinik fuer Frauenheilkunde, Universitaetsklinikum des Saarlandes, Homburg/Saar; Kinderklinik & Klinik fuer Frauenheilkunde, Klinikum Saarbruecken, Saarbruecken. Italy (Emilia Romagna): Azienda Ospedaliero-universitaria di Modena, Modena; Azienda Ospedaliero-universitaria di Bologna, Bologna; Ospedale Maggiore C.A. Pizzardi, Bologna; Azienda Ospedaliera di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia; Azienda Ospedaliero-universitaria di Parma, Parma; Ospedale Infermi, Rimini; Ospedale M. Bufalini, Cesena; Azienda Ospedaliero-universitaria di Ferrara, Ferrara; Ospedale Santa Maria delle Croci, Ravenna; Ospedale Morgagni—Pierantoni, Forlì; Ospedale Guglielmo da Saliceto, Piacenza; Ospedale Civile Nuovo Santa Maria della Scaletta, Imola; Ospedale Degli Infermi, Faenza; Ospedale Santa Maria Bianca, Mirandola; Ospedale Civile Guastalla, Guastalla; Ospedale SS. Annunziata, Cento; Ospedale Umberto I, Lugo; Ospedale Unico della Val D'Arda, Fiorenzuola D'Arda; Ospedale San Secondo, Fidenza; Ospedale B. Ramazzini, Carpi; Ospedale Pavullo nel Frignano, Pavullo nel Frignano; Nuovo Ospedale Civile di Sassuolo, Sassuolo; Ospedale di Bentivoglio, Bentivoglio. Italy (Lazio Region): Policlinico Umberto I; Policlinico A. Gemelli; Azienda Ospedaliera San Camillo; Azienda Ospedaliera San Giovanni; Azienda Ospedaliera San Filippo Neri; Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù; Ospedale Belcolle-Viterbo; Ospedale Sant'Eugenio; Ospedale SG Calibita Fatebenefratelli; Ospedale S. Pietro Fatebenefratelli; Policlinico Casilino. Italy (Marche): Azienda Ospedaliero-universitaria Ospedali Riuniti Umberto I—G.M. Lancisi—G. Salesi, Ancona; Ospedale Generale Provinciale C.G. Mazzoni, Ascoli Piceno; Ospedale Generale Provinciale Macerata, Macerata; Azienda Ospedaliera San Salvatore, Pesaro; Ospedale A. Murri, Fermo; Ospedali Riuniti di Jesi, Jesi; Ospedale Civile E. Profili, Fabriano; Ospedale Santa Croce, Fano. The Netherlands (Eastern & Central): Radboudumc Nijmegen; Wilhelmina Childrens Hospital Utrecht; Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital Nijmegen; Maasziekenhuis Pantein Boxmeer; Bernhoven Hospital Uden; Gelderse Vallei Hospital Ede; Rijnstate Hospital Zevenaar; Rijnstate Hospital Arnhem; Slingeland Hospital Doetinchem; Regional Hospital Koningin Beatrix Winterswijk; Gelre Hospital Zutphen; Meander Medical Center Amersfoort; Gelre Hospital Apeldoorn; Diakonessenhuis Utrecht; Zuwe Hofpoort Hospital Woerden; Tergooi Hilversum; Hospital Rivierenland Tiel; St Antonius Hospital Nieuwegein; TweeSteden Hospital Tilburg; St Elisabeth Hospital Tilburg; Deventer Hospital Deventer; Tergooi Hospital Blaricum. Poland: Department of Neonatology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences (III level); Szpital Wojewódzki w Poznaniu (II level); Szpital Miejski im. Franciszka Raszei w Poznaniu (II level); Specjalistyczny Zespół Opieki Zdrowotnej nad Matką i Dzieckiem w Poznaniu, Szpital Św. Rodziny (II level); Wojewódzki Szpital Zespolony im. L. Perzyny w Kaliszu (II level); Wojewódzki Szpital Zespolony w Koninie (II level); Wojewódzki Szpital Zespolony w Lesznie (II level); Szpital Specjalistyczny im. Stanisława Staszica w Pile (II level); Zespół Zakładów Opieki Zdrowotnej w Ostrowie Wielkopolskim (III level); Szpital Powiatowy im. Professor Romana Drewsa w Chodziez˙y (I level); Zespół Zakładów Opieki Zdrowotnej w Czarnkowie (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zespół Opieki Zdrowotnej w Gostyniu (I level); Zespół Opieki Zdrowotnej w Gnieźnie (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej w Grodzisku Wielkopolskim (I level); Zespół Zakładów Opieki Zdrowotnej w Jarocinie (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej w Ke˛pnie (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej w Kole (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej w Kościanie (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej w Krotoszynie (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej im. K. Hołygi w Nowym Tomyślu (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej w Obornikach (I level); Zespół Zakładów Opieki Zdrowotnej w Ostrzeszowie (I level); Pleszewskie Centrum Medyczne w Pleszewie (II level); Szpital Powiatowy w Rawiczu (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej w Mie˛dzychodzie (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej w Słupcy (I level); Szpital w Śremie (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej im. Dr J. Dietla w Środzie Wielkopolskiej (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej w Szamotułach (I level); Szpital Powiatowy im. Jana Pawła II w Trzciance (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej w Turku (I level); Zespół Opieki Zdrowotnej w Wągrowcu (I level); Samodzielny Publiczny Zakład Opieki Zdrowotnej w Wolsztynie (I level); Szpital Powiatowy we Wrześni (I level); Szpital Powiatowy w Wyrzysku (I level); Szpital Powiatowy im. A. Sokołowskiego w Złotowie (I level). Portugal (Northern Region); Centro Hospitalar de Entre o Douro e Vouga, E.P.E.—Hospital de São Sebastião; Centro Hospitalar de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, E.P.E.—Hospital São Pedro; Centro Hospitalar de Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho, E.P.E.—Unidade II; Centro Hospitalar do Alto Ave, E.P.E.—Unidade de Guimarães; Centro Hospitalar do Médio Ave, E.P.E.—Unidade de Famalicão; Centro Hospitalar do Porto, E.P.E.—Maternidade Júlio Dinis; Centro Hospitalar do Tâmega e Sousa, E.P.E.—Hospital Padre Américo; Centro Hospitalar Póvoa de Varzim—Vila do Conde, E.P.E.—Unidade da Póvoa de Varzim; Centro Hospitalar São João, E.P.E.—Hospital São João; Hospital de Braga; Unidade Local de Saúde de Matosinhos, E.P.E.—Hospital Pedro Hispano; Unidade Local de Saúde do Alto Minho, E.P.E.—Hospital de Santa Luzia; Unidade Local de Saúde do Nordeste, E.P.E.—Unidade de Bragança. Portugal (Lisbon and Tagus Valley Region) : Centro Hospitalar Barreiro Montijo, E.P.E.- Hospital Nossa Senhora do Rosário; Centro Hospitalar de Lisboa Central, E.P.E.—Hospital Dona Estefânia; Centro Hospitalar de Lisboa Central, E.P.E.—Maternidade Alfredo da Costa; Centro Hospitalar de Lisboa Ocidental, E.P.E.—Hospital de São Francisco Xavier; Centro Hospitalar de Setúbal, E.P.E.—Hospital São Bernardo; Centro Hospitalar do Médio Tejo, E.P.E.—Hospital Doutor Manoel Constâncio; Centro Hospitalar do Oeste—Unidade de Caldas da Rainha; Centro Hospitalar do Oeste—Unidade de Torres Vedras; Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte, E.P.E.—Hospital Santa Maria; Hospital Cuf Descobertas; Hospital da Luz; Hospital de Cascais Dr. José de Almeida; Hospital de Santarém, E.P.E.; Hospital Garcia de Orta, E.P.E.; Hospital Lusíadas Lisboa; Hospital Professor Doutor Fernando Fonseca, E.P.E.; Hospital Vila Franca de Xira. Sweden (Stockholm): Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Danderyd Hospital, Stockholm; BB Stockholm AB, Danderyd Hospital, Stockholm; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Karolinska University Hospital (units in Solna and Huddinge), Stockholm; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sodersjukhuset (Stockholm South General Hospital), Stockholm; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sodertalje Hospital; Department of Neonatal Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital (units in Danderyd, Solna and Huddinge), Stockholm; Sachs' Children and Youth Hospital, Stockholm. UK (Northern Region): Royal Victoria Infirmary Newcastle on Tyne; James Cook University Hospital Middlesbrough; North Tees University Hospital Stockton; Sunderland Royal Hospital; Wansbeck Hospital Ashington; Queen Elizabeth Hospital Gateshead; North Tyneside General Hospital; South Tyneside General Hospital; Cumberland Infirmary Carlisle; West Cumberland Infirmary. UK (East Midlands—Yorkshire & Humber): Chesterfield Royal Hospital;Bassetlaw District General Hospital;Kings Mill Hospital;Royal Derby Hospital;Nottingham City Hospital;Nottingham Queen's Medical Centre;Lincoln County Hospital;Boston Pilgrim Hospital;University Hospitals of Leicester (LGH + LRI);Kettering General Hospital;Northampton General Hospital;Grimsby Diana Princess of Wales Hospital;Scunthorpe General Hospital;Barnsley District General Hospital;Rotherham District General Hospital;Doncaster Royal Infirmary;Jessop Wing Sheffield;Airedale District General Hospital;Bradford Royal Infirmary;Dewsbury District General Hospital;Halifax Calderdale Royal Infirmary;Harrogate District General Hospital;Hull Royal Infirmary;Leeds General Infirmary; Leeds St James's;Scarborough District General Hospital;York District Hospital;Wakefield Pinderfields General Hospital.

Collaborators: Epice Research Group: BELGIUM: Flanders (E Martens, G Martens, P Van Reempts); DENMARK: Eastern Region (K Boerch, A Hasselager, L Huusom, O Pryds, T Weber); ESTONIA (L Toome, H Varendi); FRANCE: Burgundy, Ile-de France and Northern Region (PY Ancel, B Blondel, A Burguet, PH Jarreau, P Truffert); GERMANY: Hesse (RF Maier, B Misselwitz, S Schmidt), Saarland (L Gortner); ITALY: Emilia Romagna (D Baronciani, G Gargano), Lazio (R Agostino, D DiLallo, F Franco), Marche (V Carnielli), M Cuttini; NETHERLANDS: Eastern & Central (C Koopman-Esseboom, A Van Heijst, J Nijman); POLAND: Wielkopolska (J Gadzinowski, J Mazela); PORTUGAL: Lisbon and Tagus Valley (LM Graça, MC Machado), Northern region (C Rodrigues, T Rodrigues), H Barros; SWEDEN: Stockholm (AK Bonamy, M Norman, E Wilson); UK: East Midlands and Yorkshire and Humber (E Boyle, ES Draper, BN Manktelow), Northern Region (AC Fenton, DWA Milligan); INSERM, Paris (J Zeitlin, M Bonet, A Piedvache).

Contributors: HTW participated in the study design, conducted the data analysis, drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. LH and TW contributed to the study design, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. AP participated in the study design, conducted the data analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. SS and MN contributed to the study design, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. JZ designed and conceptualised the study, conducted the data analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: The research leading to these results received funding from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme ([FP7/2007-2013]) under grant agreement No 259882. Funding for this open access publication was provided by the FP7 Post-Grant Open Access Pilot. Additional funding was received in the following regions: France (French Institute of Public Health Research/Institute of Public Health and its partners the French Health Ministry, the National Institute of Health and Medical Research, the National Institute of Cancer, and the National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy; grant ANR-11-EQPX-0038 from the National Research Agency through the French Equipex Program of Investments in the Future; and the PremUp Foundation); Poland (2012–2015 allocation of funds for international projects from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education); Sweden (regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet, and by the Department of Neonatal Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital); UK (funding for The Neonatal Survey from Neonatal Networks for East Midlands and Yorkshire & Humber regions).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained in each region from regional and/or hospital ethics committees, as required by national legislation. The European study was also approved by the French Advisory Committee on Use of Health Data in Medical Research and the French National Commission for Data Protection and Liberties.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: E Martens, G Martens, P Van Reempts, K Boerch, A Hasselager, O Pryds, L Toome, H Varendi, PY Ancel, B Blondel, A Burguet, PH Jarreau, P Truffert, RF Maier, B Misselwitz, L Gortner, D Baronciani, G Gargano, R Agostino, D DiLallo, F Franco, V Carnielli, M Cuttini, C Koopman-Esseboom, A Van Heijst, J Nijman, J Gadzinowski, J Mazela, LM Graça, MC Machado, C Rodrigues, T Rodrigues, H Barros, AK Bonamy, E Wilson, E Boyle, ES Draper, BN Manktelow, AC Fenton, DWA Milligan, and M Bonet

References

- 1.Duley L, Gülmezoglu AM, Henderson-Smart DJ et al. Magnesium sulphate and other anticonvulsants for women with pre-eclampsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(11):CD000025 10.1002/14651858.CD000025.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crowther CA, Brown J, McKinlay CJD et al. Magnesium sulphate for preventing preterm birth in threatened preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(8):CD001060 10.1002/14651858.CD001060.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R. Antenatal magnesium sulfate for the prevention of cerebral palsy in preterm infants less than 34 weeks’ gestation: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:595–609. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cahill AG, Caughey AB. Magnesium for neuroprophylaxis: fact or fiction? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:590–4. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doyle LW, Crowther CA, Middleton P et al. Magnesium sulphate for women at risk of preterm birth for neuroprotection of the fetus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(1):CD004661 10.1002/14651858.CD004661.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf HT, Hegaard HK, Greisen G et al. Treatment with magnesium sulphate in pre-term birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Obstet Gynaecol 2012;32:135–40. 10.3109/01443615.2011.638999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huusom LD, Secher NJ, Pryds O et al. Antenatal magnesium sulphate may prevent cerebral palsy in preterm infants-but are we convinced? Evaluation of an apparently conclusive meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. BJOG 2011;118:1–5. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02782.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugimoto J, Romani AM, Valentin-Torres AM et al. Magnesium decreases inflammatory cytokine production: a novel innate immunomodulatory mechanism. J Immunol 2012;188:6338–46. 10.4049/jimmunol.1101765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowling O, Chatterjee PK, Gupta M et al. Magnesium sulfate reduces bacterial LPS-induced inflammation at the maternal-fetal interface. Placenta 2012;33:392–8. 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galinsky R, Davidson JO, Drury PP et al. Magnesium sulphate and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular adaptations to asphyxia in preterm fetal sheep. J Physiol (Lond) 2016;594:1281–93. 10.1113/JP270614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dasgupta S, Ghosh D, Seal SL et al. Randomized controlled study comparing effect of magnesium sulfate with placebo on fetal umbilical artery and middle cerebral artery blood flow in mild preeclampsia at ≥ 34 weeks gestational age. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2012;38:763–71. 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01806.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillon TER, Pels A, von Dadelszen P et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a systematic review of international clinical practice guidelines. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e113715 10.1371/journal.pone.0113715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO recommendations for Prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44703/1/9789241548335_eng.pdf. (Retrieved 25 April 2016).

- 14.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Preterm labour and birth. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0080792/pdf/PubMedHealth_PMH0080792.pdf (Retrieved 25 April 2016).

- 15.Clinical practice guideline. Antenatal magnesium sulphate for fetal neuroprotection. http://www.hse.ie/eng/about/Who/clinical/natclinprog/obsandgynaeprogramme/mgso.pdf (Retrieved 25 April 2016).

- 16.Prevention of preterm birth in women at risk: selected topics [Internet]. (cited 3 August 2016). https://kce.fgov.be/sites/default/files/page_documents/KCE_228Cs_Preterm birth_Synthesis.pdf (Retrieved 25 April 2016).

- 17.De Silva DA, Sawchuck D, von Dadelszen P et al. Magnesium sulphate for eclampsia and fetal neuroprotection: a comparative analysis of protocols across Canadian tertiary perinatal centres. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37:975–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bouet P, Brun S, Madar H et al. Implementation of an antenatal magnesium sulfate protocol for fetal neuroprotection in preterm infants. Sci Rep 2015;5:14732 10.1038/srep14732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeitlin J, Manktelow BN, Piedvache A et al. Use of evidence based practices to improve survival without severe morbidity for very preterm infants: results from the EPICE population based cohort. BMJ 2016;354:i2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management (NICE guidelines) [Internet]. (cited 4 August 2016). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg107/chapter/1-Guidance.

- 21.Schaap TP, Knight M, Zwart JJ et al. Eclampsia, a comparison within the International Network of Obstetric Survey Systems. BJOG 2014;121:1521–8. 10.1111/1471-0528.12712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaatinen N, Ekholm E. Eclampsia in Finland; 2006 to 2010. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016;95:787–92. 10.1111/aogs.12882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourret B, Compère V, Torre S et al. [Magnesium sulfate in the prophylaxis of eclampsia: a retrospective study]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2012;31:933–6. 10.1016/j.annfar.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lumbiganon P, Gülmezoglu AM, Piaggio G et al. Magnesium sulfate is not used for pre-eclampsia and eclampsia in Mexico and Thailand as much as it should be. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:763–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bigdeli M, Zafar S, Assad H et al. Health system barriers to access and use of magnesium sulfate for women with severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia in Pakistan: evidence for policy and practice. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e59158 10.1371/journal.pone.0059158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ridge AL, Bero LA, Hill SR. Identifying barriers to the availability and use of magnesium sulphate injection in resource poor countries: a case study in Zambia. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:340 10.1186/1472-6963-10-340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sevene E, Lewin S, Mariano A et al. System and market failures: the unavailability of magnesium sulphate for the treatment of eclampsia and pre-eclampsia in Mozambique and Zimbabwe. BMJ 2005;331:765–9. 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magnesium Sulfate Before Anticipated Preterm Birth for Neuroprotection. Committee opinion. March 2010. (ACOG) [Internet]. (cited 9 August 2016). http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Magnesium-Sulfate-Before-Anticipated-Preterm-Birth-for-Neuroprotection

- 29.Magnesium Sulphate to Prevent Cerebral Palsy following Preterm Birth. Scientific Impact Paper No. 29. August 2011. (RCOG) [Internet]. (cited 3 August 2016). https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/scientific-impact-papers/sip_29.pdf

- 30.Costantine MM, Weiner SJ, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Effects of antenatal exposure to magnesium sulfate on neuroprotection and mortality in preterm infants: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114(2 Pt 1):354–64. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ae98c2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf HT, Hegaard HK, Pinborg AB et al. Does antenatal administration of magnesium sulphate prevent cerebral palsy and mortality in preterm infants? A study protocol. AIMS Public Heal 2015;2:727–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sample sizes after each exclusion criteria in each region (corresponds to totals in flow chart, Figure 1)

bmjopen-2016-013952supp_table1.pdf (203.9KB, pdf)

Maternal and unit factors associated with MgSO4 treatment of women with severe preeclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP after exclusion of IUGR cases

bmjopen-2016-013952supp_table2.pdf (306.1KB, pdf)

Maternal and unit factors associated with MgSO4 treatment after exclusion of unit policy variables

bmjopen-2016-013952supp_table3.pdf (311.8KB, pdf)

Comparison of Excluded and Included Units

bmjopen-2016-013952supp_table4.pdf (315.9KB, pdf)