Abstract

Splenic diseases are rare. Tumours of the spleen are classified as either benign or malignant. Primary benign tumours of the spleen are extremely rare, identified on surgery and autopsy, accounting for <0.007% of all splenic tumours. Splenic lymphangiomas are benign cystic tumours resulting from congenital malformations of the lymphatic system that appear as a single or multiple lesions of the spleen. It mainly affects children and is rarely manifested after the age of 20 years of age. We report a case of cystic lymphangioma of spleen in a 40-year-old woman admitted with a huge mass in the abdomen, which on imaging found to be a cystic mass arising from spleen. On laparotomy the spleen was found occupying a major part of the abdomen. Splenectomy was performed and histopathological examination revealed it to be a cystic lymphangioma of spleen. This case report emphasises on the rarity of the case at this age and the sheer size of the tumour, being largest until as per our knowledge.

Background

Splenic tumours are classified as either benign or malignant. Lymphangioma is a benign neoplasm, mostly cystic and generally occurs under the age of 2 years with no difference in incidence between boys and girls. Lymphangiomas can occur sporadically in the mediastinum, retroperitoneum and internal organs. Splenic lymphangioma is a very rare condition. From 1939 to 1990 around 180 cases of splenic lymphangioma have been reported.1 From 1990 to 2010, only nine cases have been reported in the literature. The report by Goh et al2 published in 2005 reported 14 intra-abdominal lymphangiomas over a period of 15 years of which only one patient presented with a splenic lymphangioma. The rate of malignant transformation is low with good prognosis.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old married woman was admitted with a history of a distended abdomen since 4 months with diffuse vague abdominal pain. She had no history of nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, fever, weight loss, and loss of appetite as well as no history of previous trauma to the abdomen. Her bladder and bowel habits were normal. She was moderately built and nourished. There was severe pallor of palpebral conjunctiva. She was afebrile with stable vitals. On inspection, a mass was seen in the upper abdomen covering the left hypochondrium (figure 1). Palpation of the abdomen revealed splenomegaly of size 18×12 cm extending up to right hypochondrium and right iliac fossa, which was firm, non-tender and moving with respiration. Finger insinuation was not possible between the mass and the left costal margin.

Figure 1.

Preoperative photograph of the abdomen.

Investigations

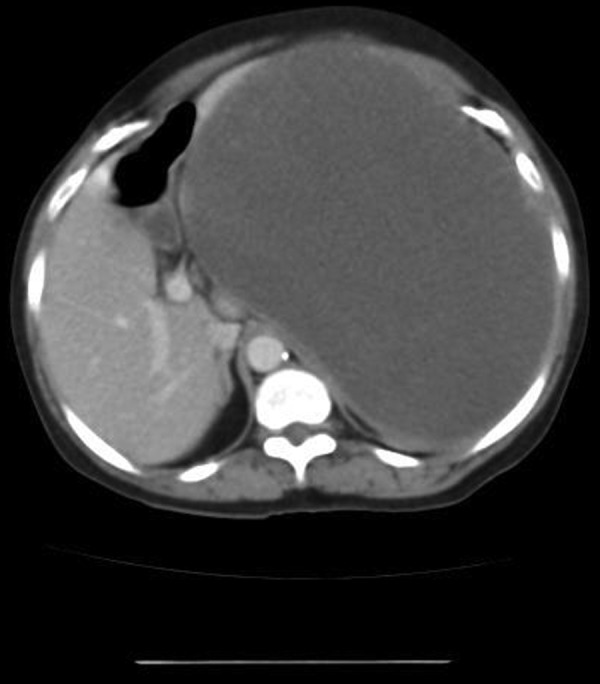

Her haemoglobin was 10 g%. Peripheral smear showed normocytic normochromic anaemia. Other blood and urine investigations were normal. Plain abdomen X-ray showed a large opacity displacing the bowel loops to right side. Ultrasound scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed massive splenomegaly with both hypoechoic and hyperechoic areas. A contrast-enhanced CT scan was carried out which revealed a 15×10 cm splenic tumour (figure 2) with prominent enhancement of the solid components with hypodense areas of the cystic components with no ascites (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Non-contrast CT scan photograph of the splenic mass.

Figure 3.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan photograph of the splenic mass.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis included a cystic lymphangioma of spleen, hydatid cyst, haemangioma, and pseudocysts of spleen.

Treatment

Preoperative vaccination against capsulated organisms was done 4 weeks prior to surgery. Owing to the massive size of the spleen, open splenectomy was planned. Under general anaesthesia, an upper midline incision was made. On opening the peritoneum, a massive spleen was encountered occupying a major part of the peritoneal cavity. Owing to the massive size of the spleen, entry into the lesser sac for identifying the splenic vessels was not feasible. The spleen was mobilised medially by dissecting the phrenicosplenic, splenocolic and lienorenal ligaments. Short gastric vessels were dissected in the gastrosplenic ligament. Hilar dissection was performed with extreme caution to avoid injury to the tail of the pancreas. Splenic artery and vein were identified and were dissected after doubly ligating them individually. The spleen was removed and the abdomen was closed after meticulous haemostasis. The spleen was sent for histopathological examination.

Outcome and follow-up

The weight of the spleen was about 5000 g and it measured 24×23×14 cm (figure 4). The cut section showed multiple cystic cavities involving almost the whole spleen, filled with gelatinous mucoid material (figure 5). On microscopic examination, multiple dilated lymph sacs filled with lymph were observed (figure 6) and final diagnosis of cystic lymphangioma of spleen was made. Immunohistochemical staining was negative for CD34 (figure 7) and CD31 (figure 8) confirming the benign nature of the tumour. The postoperative period was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the third postoperative day. The patient made complete recovery and was free of disease after 4 months. On follow-up after 6 months the patient is doing well and ultrasonogram of the abdomen showed no signs of recurrent disease.

Figure 4.

Gross appearance of the spleen removed measuring 24×23×14 cm.

Figure 5.

Cut section of the removed spleen showing multiple cystic spaces.

Figure 6.

Histopathological appearance of splenic lymphangioma showing multiple dilated lymphatic spaces filled with lymph.

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemical staining showing lymph spaces negative for CD34.

Figure 8.

Immunohistochemical staining showing lymph spaces negative for CD31.

Discussion

Tumours of the spleen are rare. Classification of splenic tumours is illustrated in the figure 9 below.3 4

Figure 9.

Classification of splenic tumours.

Lymphangioma is a benign neoplasm resulting from the malformation of the lymphatic system. It is composed of endothelial lined cysts containing lymphs. They generally occur under the age of 2 years with no sexual preponderance.5 In total 95% of lymphangiomas occur in the head and neck, axillary regions in locations of subcutaneous primitive lymph sacs where they are often referred to ‘cystic hygromas’.6 However, the most common site of intra-abdominal lymphangioma is retroperitoneum followed by small bowel mesentery. Splenic lymphangioma is a very rare condition and account for <0.007% of all splenic tumours identified on surgery and autopsy.7 Lymphangioma is less commonly encountered in the mediastinum, adrenal gland, kidney, bone, omentum, gastrointestinal tract, retroperitoneum, spleen, liver and pancreas.8 Cystic, benign, slow growing splenic tumours are usually seen in children, detected before the end of second year of life and rarely manifests after 20 years of age. Lymphangioma can involve the spleen in the form of single or multiple cysts,9 or it can be a part of multivisceral involvement also known as systemic cystic angiomatosis.10 They are generally considered to be a developmental malformation in which obstruction or agenesis of the lymphatic tissue results in lymphangiectasia, which is caused by the lack of normal communication of the lymphatic system. It can also occur due to bleeding or inflammation of the lymphatic system which causes an obstruction leading to additional lymphangiomas.

Isolated splenic lymphangioma can present with different manifestations. It is asymptomatic in the majority of cases. Large cystic lesions may attain sufficient size to cause significant splenomegaly and left upper quadrant symptoms. Symptoms are usually related to splenic size and manifest as left upper quadrant pain, abdominal distension, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting and a palpable mass. The complications associated with more extensive or larger lymphangiomas of the spleen include bleeding, consumptive coagulopathy, hypersplenism and portal hypertension.11 The effect of abdominal mass produced by the lymphangioma when it exceeds 3000–4000 g can occasionally lead to diaphragmatic immobility and consequent atelectasis or pneumonia. Reversible hypertension due to renal artery compression is rarely observed. Acute abdominal pain or a rapid increase in size can occur because of infection or rupture of a cyst.12 The radiological differential diagnosis of primary vascular tumours of the spleen is often difficult to achieve, because of the frequent overlap of their features.13

The angiographic findings include well-defined avascular lesions of varying size scattered throughout the spleen, stretching of the intraparenchymal arterial branches and an absence of neovascularity, arterial shunting, or venous pooling. A characteristic ‘Swiss cheese’ appearance of the spleen has been considered to be pathognomonic.14

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy is contraindicated because of the bleeding risk and limited amount of tissue accessible for accurate diagnosis.15

Confirmation of the diagnosis is by histopathological examination after the removal of the spleen.16

Histological analysis—capillary, cavernous and cystic lymphangioma—consists of a single layer of flattened epithelium-lined spaces between fat, fibrotic and lymphatic structures, which are filled with eosinophilic proteinaceous material. Hyalinisation and calcification of the fibrous connective tissue may be present.

Flow cytometry/immunohistochemical staining of the endothelium demonstrates reactivity with CD31, CD34, factor VIII related antigen, VEGF-3, PROX-1 and monoclonal antibody D240.

The postoperative recurrence rate and the rate of transformation into malignancy is low and the prognosis is good.17

Complications include rupture with peritonitis and invasive haemorrhage, infection, abscess formation, pleural effusion or empyema.18

Similar case reports of cystic lymphangioma of spleen in the literature are illustrated in the table 1.19–23

Table 1.

Review of similar cases of cystic lymphangioma of spleen in adults

| Serial number | Case report | Year | Age of the patient | Sex of the patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vezzoli et al | 2000 | 65 | Female |

| 2 | Solomou et al | 2003 | 43 | Female |

| 3 | Xu et al | 2011 | 15 | Female |

| 4 | Verghese et al | 2013 | 33 | Female |

| 5 | Marwah et al | 2014 | 47 | Female |

Wahab, et al18 reported three cases of lymphangiomatous cysts of the spleen in the year 1998, and Kim, et al24 reported three cases of splenic lymphangioma in 2002.

Learning points.

Rare congenital malformation of the lymphatic system.

Splenic lymphangioma mainly affects children and rarely manifests after 20 years of age.

Manifests usually as significant splenomegaly with left upper quadrant pain, nausea, abdominal distension.

Differential diagnosis in adults is a parasitic (ie, hydatid) cyst of spleen.

Symptomatic patients are treated by splenectomy and diagnosis is confirmed by histopathological examination.

Acknowledgments

The case was identified by Dr Sushama Surapaneni and Dr B Rakesh of Department of General Surgery, KIMS & RF, Amalapuram. The histopathology and immunohistochemistry slide photographs were provided with the permission of Dr Sanjjev Rao and Dr Deepthi Sahoo, Pathologists, KIMS & RF, Amalapuram, East Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh, India.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Tejokrishna Kalluri at @Tejo91

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Alerci M, Dore R. Computed tomography of cystic lymphangioma in a wandering spleen. Acta Radiol 1990;31:589–90. 10.1177/028418519003100611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goh BK, Tan YM, Ong HS et al. Intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal lymphangiomas in paediatric & adult patients. World J Surg 2005;29:837–40. 10.1007/s00268-005-7794-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowler RH. Collective review: non-parasitic benign cystic tumours of the spleen. Int Abstr Surg 1953;96:209–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edgerton MT, Hiebert JM. Vascular and lymphatic tumours in infancy, childhood and adult hood: challenge of diagnosis and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer 1978;2:1–44. 10.1016/S0147-0272(78)80001-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung SH, Park YS, Jo YJ et al. Asymptomatic lymphangioma involving spleen and retroperitoneum in adults. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:5620–3. 10.3748/wjg.15.5620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talukdar S, Alagaratnam S, Sinha A et al. Giant cystic lymphangioma in childhood: a rare differential for the acute abdomen. BMJ Case Reports 2011;2011:pii: bcr0420114105. 10.1136/bcr.04.2011.4105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L-W, Chien R-N, Yen C-L et al. Splenic tumour: a clinicopathological study. Int J Clin Pract 2004;58:924–7. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang CH, Hsieh CB, YU JC et al. A case of lymphangioma of the spleen. J Med Sci 2004;24:109–12. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgenstern H, Rosenberg J, Geller SA. Tumours of the spleen. World J Surg 1985;9:468–76. 10.1007/BF01655283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seekler SG, Rubin H, Rabinowitz JC. Systemic lymphangiomatosis. Am J Med 1964;37:976–86. 10.1016/0002-9343(64)90138-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becilacqua G, Toni G, Tuoni M. A case of cavernous hemangioma of the spleen. Tumori 1976;62:485–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kosir MA, Sonnino RE, Gauderer MWL. Paediatric abdominal lymphangiomas; a plea for early recognition. J Paediatr Surg 1991;26:1309–13. 10.1016/0022-3468(91)90607-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ros PR, Moser RP Jr, Dachman AH et al. Hemangioma of the spleen: radiologic-pathologic correlation in ten cases. Radiology 1987;162:73–7. 10.1148/radiology.162.1.3538155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tuttle RJ, Minielly JA. Splenic cystic lymphangiomatosis. Radiology 1978;126:47–8. 10.1148/126.1.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alkofer B, Lepennec V, Chiche L. Splenic cysts and tumours: diagnosis and management. Jchir (Paris) 2005;142:6–13. 10.1016/S0021-7697(05)80830-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anadol AZ, Oguz M, Bayramoglu N et al. Cystic lymphangioma of the spleen mimicking hydatid disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998;26:309–11. 10.1097/00004836-199806000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Witzel K, Kronsbein H, Pleser M et al. Intra abdominal cystic lymphangioma in childhood. Report of 2 cases. Zentrabl Chir 1999;124:159–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdel-Wahab M, Abou-Elenim A, Sultan A et al. Lymphangiomatous cysts of the spleen. Report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology 1998;45:2101–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vezzoli M, Ottini E, Montagna M et al. Lymphangioma of the spleen in an elderly patient. Hematologica 2000;85:314–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solomou EG, Patriarheas GV, Mpadra FA et al. Asymptomatic adult cystic lymphangioma of the spleen: case report and review of the literature. Magn Reson Imaging 2003;21:81–4. 10.1016/S0730-725X(02)00624-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu GP, Shen HF, Yang LR et al. Splenic cystic lymphangioma in a young woman: case report and literature review. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2011;74:334–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verghese BG, Kashinath SK, Kanth RR. Lymphangioma of the spleen—a rare tumor rarely seen in adult: a case report and a comprehensive literature review. Euroasian J Hepato Gastroenterol 2013;3:64–9. 10.5005/jp-journals-10018-1066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marwah N, Sangwan M, Ralli M et al. Cystic lymphangioma of spleen: a rare case report. Int J Sci Stud 2014;2:40–2. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim MJ, Cho KJ, Han EM et al. Splenic lymphangioma—a report of three cases. Korean J Pathol 2002;36:416–19. [Google Scholar]