Abstract

Trypanosoma equiperdum is the causative agent of dourine, a sexually-transmitted infection of horses. This parasite belongs to the subgenus Trypanozoon that also includes the agent of sleeping sickness (Trypanosoma brucei) and surra (Trypanosoma evansi). We herein report the genome sequence of a T. equiperdum strain OVI, isolated from a horse in South-Africa in 1976. This is the first genome sequence of the T. equiperdum species, and its availability will provide important insights for future studies on genetic classification of the subgenus Trypanozoon.

Keywords: Dourine, Trypanosoma equiperdum, Whole-genome sequencing, Trypanozoon.

Introduction

Trypanosoma equiperdum is a flagellated protozoon that causes dourine in horses and other members of the Equidae family. This sexually-transmitted infection is a World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) notifiable disease. The OIE terrestrial animal health code considers dourine as non-treatable and imposes a stamping-out policy for affected animals to recover a country free status 1. The diagnosis of dourine is problematic since the clinical signs of this disease in horses are in many ways similar to those of surra, a trypanosomosis transmitted by biting flies and caused by Trypanosoma evansi 2. Both dourine and surra are characterised by non-constant symptoms that can include: anemia, edema, lethargy, fever, weight loss, incoordination, paralysis of the hind limbs, facial paralysis eventually leading to the death of infected animals 3. To date, phylogenetic analyses show that T. equiperdum and T. evansi are not monophyletic and should therefore be considered as subspecies of Trypanosoma brucei, a parasite causing sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in animals 4. In this context, we herein report the genome sequence of T. equiperdum Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute (OVI), which was isolated in 1976 from the blood of a horse in South Africa 5.

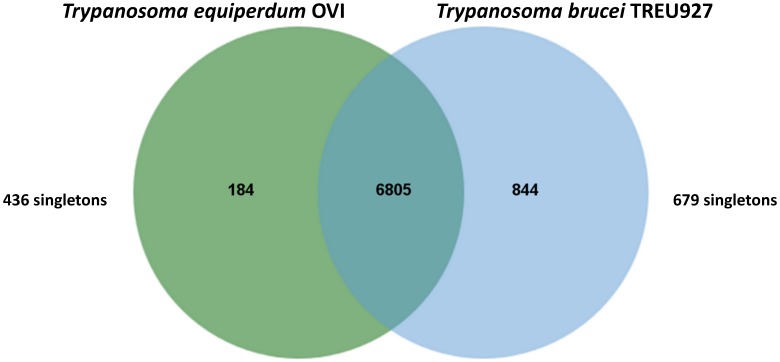

Trypanosomes (T. equiperdum OVI) were purified from the blood of infected rats using diethylaminoethyl cellulose (DE52) 6 and genomic DNA was isolated with the Machere-Nagel NucleoSpin® Tissue kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sequencing library was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq instrument with 2×150-bp paired-end reads, according to standard Illumina protocols (carried out by Beckman Coulter Genomics, Danvers, MA). In total, 24,282,070 paired-end reads representing an average coverage of ~104 -fold were generated. Prior to assembly, adapter sequences were trimmed 7 and digital normalisation was performed to reduce the data set without losing information 8. Following normalisation, 5,770,258 reads were assembled using Velvet version 1.2.03 9 with a range of k-mer values from 25 to 85. Assembled contigs of less than 1,000 bp were disregarded. Contigs of the best assembly, provided by k-mer length of 33, were extended with SSAKE (default parameter values) using Velvet generated contigs as “seeds” and the short-reads unused by Velvet for their extension 10. The genome was assembled into 2,026 contigs (>1000 bp) giving a consensus length of 26,228,029 bp. The genomic sequence was then annotated by functional annotation transfer using the parasite genome annotation pipeline Companion 11 with Trypanosoma brucei TREU927 as a reference organism. A total of 7,668 Coding DNA Sequences (CDSs) was predicted. The analysis of orthologous CDS between Trypanosoma equiperdum OVI and Trypanosoma brucei TREU927 shows that these parasites share a total of 6,805 ortholog clusters, confirming their close relatedness (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Venn diagram showing the results of OrthoMCL v1.4 analysis of orthologous CDS between Trypanosoma equiperdum OVI and Trypanosoma brucei TREU927. This Venn diagram show shared and species-specific protein-coding gene clusters in the genomes T. equiperdum OVI (left, green) and Trypanosoma brucei TREU927 (right, blue). Singletons, i.e. genes without orthologs and paralogs in either species, are placed outside the Venn diagram to the left and right.

The T. equiperdum OVI draft genome sequence generated in this study constitutes the first genome of a strain classified as T. equiperdum; this represents a new source of knowledge that will be valuable in comparative genomic studies to shed light on the complex biological interplay between the members of the subgenous Trypanozoon, their hosts and their diseases.

This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession CZPT00000000. The version described in this paper is the second version, CZPT02000000.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by ANSES and by European Commission funding for the Reference Laboratory for Equine Diseases other than African Horse Sickness. Sascha Steinbiss is funded by the Wellcome Trust through their support of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (grant WT099198MA). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication. The authors would like to thank Emilie Antier and Coralie Pulido (ANSES, Lyon Laboratory, Plateforme d'Expérimentation Animale) for assistance in trypanosomes purification.

References

- 1.World Organisation for Animal Health. Dourine. In: OIE - Terrestrial Animal Health Code (Chapter 12.3) Paris: Office International des Epizooties; 2013. pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zablotskij VT, Georgiu C, de Waal T, Clausen PH, Claes F, Touratier L. The current challenges of dourine: difficulties in differentiating Trypanosoma equiperdum within the subgenus Trypanozoon. Rev Sci Tech. 2003;22:1087–96. doi: 10.20506/rst.22.3.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desquesnes M, Holzmuller P, Lai DH, Dargantes A, Lun ZR, Jittaplapong S. Trypanosoma evansi and surra: a review and perspectives on origin, history, distribution, taxonomy, morphology, hosts, and pathogenic effects. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:194176. doi: 10.1155/2013/194176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carnes J, Anupama A, Balmer O, Jackson A, Lewis M, Brown R. et al. Genome and phylogenetic analyses of Trypanosoma evansi reveal extensive similarity to T. brucei and multiple independent origins for dyskinetoplasty. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e3404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrowman PR. Experimental intraspinal Trypanosoma equiperdum infection in a horse. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1976;43:201–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanham SM, Godfrey DG. Isolation of salivarian trypanosomes from man and other mammals using DEAE-cellulose. Exp parasitol. 1970;28:521–34. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(70)90120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodt M, Roehr JT, Ahmed R, Dieterich C. FLEXBAR-flexible barcode and adapter processing for next-generation sequencing platforms. Biology. 2012;1:895–905. doi: 10.3390/biology1030895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pell J, Hintze A, Canino-Koning R, Howe A, Tiedje JM, Brown CT. Scaling metagenome sequence assembly with probabilistic de Bruijn graphs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:13272–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121464109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18:821–9. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warren RL, Sutton GG, Jones SJ, Holt RA. Assembling millions of short DNA sequences using SSAKE. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:500–1. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinbiss S, Silva-Franco F, Brunk B, Foth B, Hertz-Fowler C, Berriman M. et al. Companion: a web server for annotation and analysis of parasite genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W29–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]