ABSTRACT

The locomotor deficits in the group of diseases referred to as hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) reflect degeneration of upper motor neurons, but the mechanisms underlying this neurodegeneration are unknown. We established a Drosophila model for HSP, atlastin (atl), which encodes an ER fusion protein. Here, we show that neuronal atl loss causes degeneration of specific thoracic muscles that is preceded by other pathologies, including accumulation of aggregates containing polyubiquitin, increased generation of reactive oxygen species and activation of the JNK–Foxo stress response pathway. We show that inhibiting the Tor kinase, either genetically or by administering rapamycin, at least partially reversed many of these pathologies. atl loss from muscle also triggered muscle degeneration and rapamycin-sensitive locomotor deficits, as well as polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation. These results indicate that atl loss triggers muscle degeneration both cell autonomously and nonautonomously.

KEY WORDS: Atlastin, Degeneration, Membrane fusion, Polyubiquitin, Rapamycin

Summary: We show that Drosophila lacking atl, a gene associated with hereditary spastic paraplegia, exhibit muscle degeneration and other phenotypes that are each rescued by administering the Tor inhibitor rapamycin.

INTRODUCTION

The locomotor deficits in individuals with mutations in one of the approximately 72 genes involved in hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) are thought to result from degeneration of specific populations of neurons within the central nervous system. However, owing in large part to a lack of an animal model for any HSP, the mechanisms underlying this neurodegeneration remain elusive.

In several other neurodegenerative disorders that affect humans, such as Alzheimer's, Huntington's and Parkinson's diseases, neurodegeneration is accompanied by, and perhaps caused by, intracellular accumulation of protein aggregates containing polyubiquitin (reviewed recently in Menzies et al., 2015). These aggregates can be generated through expression of mutant misfolding proteins (Blokhuis et al., 2013), as is the case for the SOD1G85R mutation that is causal for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS; Bruijn et al., 1998). However, protein aggregates can accumulate even in cells that do not express misfolding mutants. In these cases, aggregate accumulation and degeneration appear to be linked to attenuated autophagy (Frake et al., 2015; Madeo et al., 2009), which is the process responsible for degrading polyubiquitin aggregates (Pandey et al., 2007; Snyder et al., 2003; Yao, 2010). In particular, autophagy inhibition leads to polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation (Rubinsztein, 2006), and certain genetic changes in neurodegenerative disorders identify autophagy genes. For example, the age of onset in Huntington's disease is modified by a polymorphism in autophagy gene ATG7 (Metzger et al., 2010), and an α-synuclein variant that is causal for Parkinson's disease impairs autophagy through beclin 1 inhibition (Yan et al., 2014). Furthermore, autophagy-deficient mouse neurons accumulate polyubiquitin aggregates and exhibit neurodegeneration (Komatsu et al., 2006, 2007). Although to our knowledge, polyubiquitin aggregates have not been detected in HSP, one HSP gene (spastizin, SPG15) encodes a protein that interacts with beclin 1 and participates in autophagy initiation (Vantaggiato et al., 2014). These results suggest a linkage between neurodegeneration, impaired autophagy and polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation.

Autophagy is inhibited by the target of rapamycin (Tor; CG5092 in FlyBase) kinase (Nedelsky et al., 2008), which phosphorylates and inhibits the activity of several autophagy proteins including Atg1 and Atg13 (Jung et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2011). Thus, it seemed possible that chronic Tor activation might cause polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation through autophagy inhibition. In fact, Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and Huntington's diseases are associated with Tor activation (Bové et al., 2011; Floto et al., 2007; Pei and Hugon, 2008; Ravikumar et al., 2004; Wong, 2013). In these diseases, the macrolide rapamycin, which activates autophagy by inhibiting Tor, is currently being utilized or tested as a therapeutic. However, the possibility that Tor activation and consequent polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation might be causal for the degeneration in the HSPs has not been proposed.

In this study, we report further development of the Drosophila model for the HSPs. In particular, we report behavioral, physiological and anatomical consequences conferred by loss of atlastin (atl, Spastic Paraplegia Gene 3A). We find that RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown of atl in either neurons or muscle leads to early paralysis and ultimately death. These behavioral phenotypes are accompanied by degeneration of specific muscle groups within the dorsal thorax and are preceded by accumulation of protein aggregates containing polyubiquitin within these muscles. Thus, Atl affects muscle anatomy and physiology both cell autonomously and nonautonomously. Other pathological features of muscles from neuronal atl knockdown include increased generation of reactive oxygen species and activation of a stress response pathway mediated by the JNK MAP kinase (Basket in flies) and the transcription factor Foxo. Finally, we report that global Tor inhibition accomplished by administering rapamycin at least partially suppressed the behavioral consequences of both neuronal and muscle atl knockdown, and delays polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation and degeneration of thoracic muscles. Our results raise the possibility that the neurodegeneration that is thought to occur in HSP occurs through mechanisms similar to those that underlie neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, and ALS.

RESULTS

Adult locomotor deficits and precocious mortality in neuronal atl-knockdown flies

Flies bearing a UAS-driven atl RNAi transgene exhibit a significant knockdown of Atl protein in the presence of a tub-Gal4 transgene (Orso et al., 2009). We have previously reported that pan-neuronal, RNAi-mediated atl knockdown (elav>atl-RNAi) causes age-dependent locomotor deficits in adult males (Summerville et al., 2016). Following on from this, we determined that these progressive locomotor deficits, manifested initially as paralysis and then ultimately as death, were accelerated when males were aged in vials containing single females (Fig. 1A,B). We speculated that rearing individual males and females together, rather than males alone, accelerated locomotor decline by sustaining male courtship behavior and thus increasing neuromuscular activity. To test this possibility, we increased neuromuscular activity by ectopically expressing TrpA1 in a pan-neuronal manner, resulting in the conduction of an inward current at elevated temperatures (Pan et al., 2011). We found that co-expressing elav>atl-RNAi with TrpA1, but not the neutral transgene GFP, and rearing adults at 28.5°C significantly accelerated the induction of paralysis (P<0.001, Fig. S1F) and decreased the lifespan of single males (P<0.001, Fig. S1A) to a level similar to that observed in males that had been reared in vials containing single females (Fig. 1A,C). In contrast, we detected no effect on viability with pan-neuronal TrpA1 expression in an atl+ background (Fig. 1C). We conclude that neuronal activity accelerates the locomotor decline conferred by neuronal atl knockdown.

Fig. 1.

The decreased lifespan caused by neuronal atl knockdown is accelerated by neuronal activity. (A) Males of the indicated genotypes, maintained as single flies at 25°C, were analyzed for viability (red and blue circles) and paralysis (green circles). The percentages of flies living, paralyzed or dead of 27 elav>Dcr flies and 32 elav>Dcr,atlRNAi flies are shown. (B) Males of the indicated genotypes, maintained as mating pairs at 25°C, were analyzed for viability (red and blue circles) and paralysis (green circles). Mean±s.e.m. of the percentage of flies living, paralyzed or dead from three replicates (40 animals) of elav>Dcr2 flies and three replicates (49 animals) of elav>Dcr2,atlRNAi is shown. (C) Flies of the indicated genotypes, maintained as single males at 28.5°C, were analyzed for viability (red and blue circles) and paralysis (green circles). Mean±s.e.m. of the percentage of flies living, paralyzed or dead from eight replicates (93 animals) of elav>Dcr2,atlRNAi,TrpA1 flies and eight replicates (80 animals) of elav>Dcr2,atlRNAi,GFP flies is shown. The closed black circles represent non-paralyzed viable animals (two replicates with 24 animals) of the genotype elav>Dcr2,TrpA1. (D) Males of the indicated genotypes, maintained as mating pairs at 25°C, were analyzed for viability (red and blue circles) and paralysis (green circles). Mean±s.e.m. of the percentage of flies living, paralyzed or dead of five replicates (40 animals) of elav>Dcr2,atlRNAi,atlDeOp flies and five replicates (43 animals) of elav>Dcr2,atlRNAi,GFP flies is shown. atlDeOp represents codon-deoptimized atl expressed under UAS control.

To confirm that these locomotor effects reflected specific knockdown of atl rather than non-specific off-target effects, we questioned whether expressing an atl+ transgene in neurons from these knockdown flies could suppress the locomotor deficits. Because pan-neuronal expression of atl+ causes embryonic lethality (Summerville et al., 2016), we introduced an atl+ transgene with codons deoptimized for translation in Drosophila. We found that expression of this deoptimized atl+ transgene, but not of the neutral transgene GFP, significantly delayed paralysis (P<0.001, Fig. S1F) and increased lifespan (P<0.001, Fig. S1B) in elav>atl-RNAi adults (Fig. 1D). We conclude that the progressive locomotor deficits in atl-knockdown flies specifically reflect loss of atl expression.

Muscle cell degeneration and accumulation of polyubiquitin aggregates in adults that lack atl

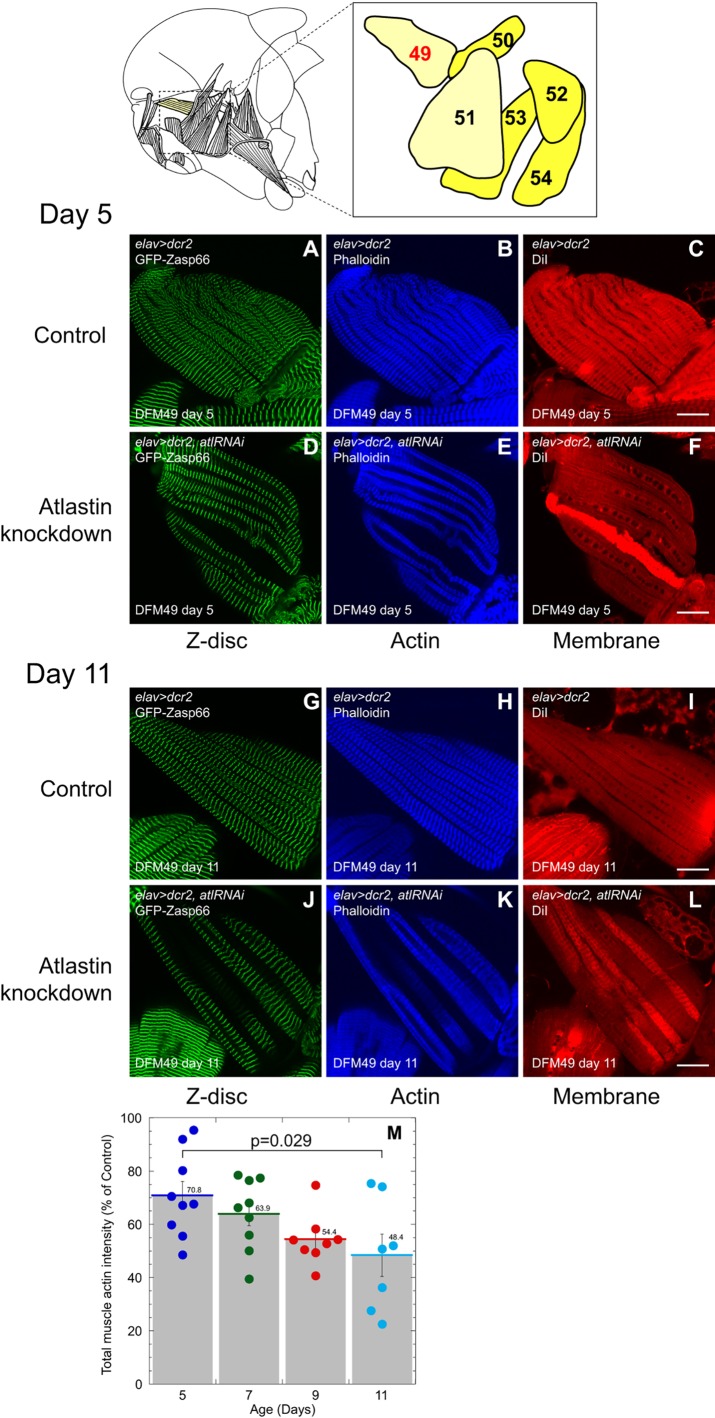

Next, we questioned if these atl knockdown males would show cellular degeneration. We imaged adult brains following application of antibodies against activated caspase-3 (also called Decay in flies) and polyubiquitin, as well as against Fas II. Fas II is preferentially expressed in the mushroom and ellipsoid bodies that contain the upper motor neurons that might be analogous to the upper motor neurons at risk in HSP. We found no anatomical abnormalities in these knockdown males (data not shown). However, muscle loss was evident when we screened dissected thoracic muscles with the actin label Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin. We also screened for general muscle anatomy and structure by introducing a GFP-tagged Z-disc gene Zasp66, as well as general membrane structure by applying the membrane dye DiI. Unexpectedly, we found that these neuronal atl-knockdown adults, but not control adults, exhibited progressive degeneration of some but not all thoracic muscles. The most striking degeneration was seen in direct flight muscles. We chose to focus on one specific direct flight muscle, DFM49 (Fig. 2, top right panels), which controls steering during flight (King and Tanouye, 1983), because of relative ease of analyzing tissue behavior during dissection and imaging. We found that atl-knockdown flies, but not control animals, exhibited some actin and Z-disc loss at day 5 (Fig. 2A–F) that became progressively more extensive through days 7, 9 and 11 (Fig. 2G–L). The application of the general membrane stain DiI suggested that muscle protein is lost from degenerating fibers rather than from complete loss of the myofibril (Fig. 2A–L). This progressive loss of actin staining, using Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin pixel intensity as a readout for actin levels and normalized to control, is shown quantified in Fig. 2M.

Fig. 2.

Progressive muscle loss in neuronal atl-knockdown flies. All animals analyzed were males reared as mating pairs. Upper panels: left, lateral view of Drosophila adult thorax, anterior is left, posterior is right (schematic adapted from Zalokar, 1947). Right, location, shape and identity of specific direct flight muscles relevant to this study are indicated. DFM49 is highlighted. (A–L) Labeling of Z-discs (A,D,G,J), actin (B,E,H,K) and cell membrane (C,F,I,L) of DFM49 in 5-day-old (A–F) and 11-day-old (G–L) adults. The control genotype (A–C and G–I) is elav>dcr2. The experimental genotype (D–F and J–L) is elav>dcr2,atlRNAi. Z-discs were labeled by expressing a GFP protein-trap insertion into Zasp66. Actin was labeled with Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin. Scale bars: 25 µm. Each image is a single slice from a confocal z-stack. (M) The DFM49 from flies at the indicated ages was outlined, and the total actin content as determined by measuring Alexa-Fluor-647 pixel intensity was determined. Actin content from elav>dcr2,atlRNAi flies is shown normalized to that of control (elav>dcr2). Each circle represents a single animal DFM49. Means±s.e.m. are indicated, and individual data points are shown. P-value of actin intensity between day-5 and day-11 flies is 0.029 (Student's t-test).

Despite the muscle degeneration observed in the atl knockdowns, motor neuron and presynaptic architecture did not appear to be strongly affected. Motor neuron innervation appeared grossly normal and the active zone component Bruchpilot was present. However, we noticed that the Bruchpilot signal appeared to be rearranged, with active zones spaced closer within atl-knockdown boutons in comparison to controls (Fig. S2). The presynaptic changes were observed only after muscle degeneration had begun, suggesting that these changes were secondary consequences of the muscle degeneration; however, we cannot exclude the possibility that these presynaptic changes were direct results of atl knockdown in this neuron.

Cellular degeneration in several neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases and ALS, are accompanied by accumulation of polyubiquitylated aggregates (Alves-Rodrigues et al., 1998; Huang and Figueiredo-Pereira, 2010). We next investigated whether muscle degeneration caused by atl loss, likewise, generates polyubiquitin aggregates. We used Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin to outline muscles and an antibody against ubiquitin to visualize aggregates. We found that the degenerating thoracic muscles, such as DFM49 and DFM50, during neuronal atl knockdown exhibited extensive reactivity with an antibody against ubiquitin, indicating the accumulation of polyubiquitin aggregates, and these aggregates were not present in control flies (Fig. 3A,B). Polyubiquitin aggregates were apparent immediately following eclosion (Fig. 3C,D) and in 5-day-old flies before degeneration was evident (Fig. 3E,F), arguing against the possibility that these aggregates are secondary consequences of degeneration.

Fig. 3.

Polyubiquitin-containing aggregates in thoracic or larval muscles from flies lacking atl. (A–H) All animals analyzed were males that had been reared as mating pairs. Thoracic muscles (A,B) or DFM49 (C–H) taken from flies of the indicated genotypes immediately following eclosion (A–D,G,H) or 5 days after eclosion (E,F) were stained with an anti-ubiquitin antibody and imaged. (A,B) Low-magnification view of several DFMs, including DFM49 and DFM50. Scale bars: 50 µm. (C–H) Higher-magnification view of DFM49 from flies of the indicated genotype and age. Scale bars: 25 µm. (I–L) Low-magnification (I,J) and high-magnification (K,L) images of ventral body wall muscles 15, 16 and 17 from w1118 or atl2 third instar larvae stained with an anti-ubiquitin antibody and imaged. Panel I also shows muscles 7 and 6 at lateral edges of the image, and panel J also shows muscles 7, 6, 13 and 12 in lateral edges of the image. Scale bar: 50 µm (I,J); 25 µm (K,L). Each image is a maximum intensity z-projection from a confocal z-stack.

To confirm that these muscle deficits reflect loss of atl in neurons, we examined muscle phenotypes in adults and larvae that were homozygous for the atl2 null mutation. In adults, we found a similar accumulation of polyubiquitin aggregates in the same muscles that had been affected by neuronal atl knockdown (Fig. 3G,H; data not shown), thus confirming that these phenotypes are caused by atl loss. atl2 adults do not survive long enough for muscle degeneration to be observed (Orso et al., 2009). In atl2 third instar larvae, we observed polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation in some but not all body wall muscles. In particular, we observed polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation in muscles 12, 13, 15, 16 and 17 from atl2 flies, but very little aggregate accumulation in muscles 6 and 7 (Fig. 3J,L). In contrast, some polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation was observed primarily in the perinuclear region in muscles from control larvae (Fig. 3I,K).

Therapeutic effects of Tor inhibition on neuronal atl-knockdown phenotypes

We were interested in understanding the mechanism underlying the accumulation of these aggregates. As described above, polyubiquitin aggregates are degraded through autophagy rather than by the proteasome (Pandey et al., 2007; Snyder et al., 2003; Yao, 2010), and inhibition of autophagy has previously been shown to lead to polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation (Rubinsztein, 2006). Because autophagy is inhibited by the Tor kinase (Nedelsky et al., 2008), which phosphorylates and inhibits the activity of several autophagy proteins including Atg1 and Atg13 (Jung et al., 2010), we reasoned that muscle Tor activation might underlie the polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation that we observed. To test this hypothesis, we determined if Tor inhibition, accomplished by feeding the Tor inhibitor rapamycin, would delay or attenuate muscle degeneration and polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation as well as the progressive locomotor deficits. We administered rapamycin in the food to adults immediately after eclosion, at the 200 µM concentration shown previously to be effective in prolonging Drosophila lifespan (Bjedov et al., 2010). We found that rapamycin administration significantly delayed the onset of paralysis (P<0.001, Fig. S1F) and increased lifespan (P=0.0114, Fig. S1C) in neuronal atl-knockdown adults (Fig. 4A). Non-paralyzed mutant flies, the most clinically beneficial phenotype, survived longer with this drug treatment. In particular, rapamycin administration increased the time to 50% for the non-paralyzed class from 10 to 13.7 days (Fig. 4A, open versus filled red circles), decreased the number of flies that were paralyzed (Fig. 4A, open versus filled green circles) and delayed death (Fig. 4A, open versus filled blue circles). Rapamycin administration also attenuated muscle degeneration and polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation (Fig. 4B–E), and significantly decreased the total polyubiquitin signal (P=0.009, Fig. 4F) and suppressed muscle degeneration, as measured by the intensity of Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin fluorescence (P=0.006, Fig. 4G). Rapamycin administration had a much greater therapeutic effect on viability in these atl-knockdown flies than on the increased lifespan reported for wild-type males (Bjedov et al., 2010).

Fig. 4.

Partial suppression of locomotor deficits, muscle degeneration and polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation through rapamycin administration. All animals analyzed were males that had been reared as mating pairs. (A) elav>dcr2,atlRNAi flies, maintained at 25°C as single mating pairs, were fed with food containing 200 µM rapamycin (solid circles) or 1% EtOH vehicle (open circles) following eclosion. Viability (blue and red circles) and paralysis (green circles) were measured. Mean±s.e.m. of the percentage of flies living, paralyzed or dead from seven replicates with 53 flies (rapamycin treated) or 54 flies (vehicle treated) is shown. (B–E) Dissected thoracic tissue from 5-day-old elav>dcr2,atlRNAi adults fed immediately following eclosion with either vehicle (1% EtOH, B,D) or 200 µM rapamycin (C,E) was fixed and stained with Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin (B,C) or an anti-ubiquitin antibody (D,E). DFM49 is outlined. Scale bar: 25 µm. Each image is a single slice from a confocal z-stack. (F–G) 5-day-old (F) or 7-day-old (G) elav>dcr2,atlRNAi males were fed with either 200 µM rapamycin (blue circles, each individual animal DFM49) or 1% EtOH (green circles, each individual animal DFM49). Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin staining was used to outline DFM49. (F) Quantification of polyubiquitin pixel intensities per µm3 in each muscle following staining with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. Mean±s.e.m. is indicated. P=0.009 by Student's t-test for rapamycin versus EtOH treatment for 5-day-old males. (G) Quantification of actin levels by determining Alexa-Fluor-647 pixel intensity following staining with Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin. Mean±s.e.m. is indicated. P=0.006 by Student's t-test for rapamycin versus EtOH treatment for 7-day-old males. The mean intensity value is given above the bars.

We also found that decreasing Tor activity by introducing one copy of the Tork17004 hypomorphic allele (Zhang et al., 2000) into neuronal atl-knockdown flies delayed onset of paralysis to a similar extent (P<0.001, Fig. S1F) and increased lifespan (P<0.001, Fig. S1D), muscle degeneration and polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation. In particular, introducing the Tork17004/+ genotype to neuronal atl-knockdown flies prolonged the life span (increasing the time at which 50% of the flies died) of the non-paralyzed class from about 8 to 13 days (Fig. 5A, open versus filled red circles), decreased the number of flies that were paralyzed (Fig. 5A, open versus filled green circles) and delayed death (Fig. 5A, open versus filled blue circles). Tork17004/+ also attenuated polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation and muscle degeneration in both 1-day-old flies (Fig. 5B–E) and 7-day-old flies (Fig. 5F–I) because the total polyubiquitin signal intensity was significantly decreased (P=0.024, Fig. 5J) and muscle degeneration, as measured using the intensity of Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin fluorescence, was suppressed (P=0.003, Fig. 5K). We conclude that inhibiting Tor activity rescues, at least partially, several pathological aspects of neuronal atl knockdown.

Fig. 5.

Partial suppression of locomotor deficits, muscle degeneration and polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation by decreasing Tor activity. All animals analyzed were males that had been reared as mating pairs. (A) elav>dcr2,atlRNAi flies (solid circles) or Tork17004/+; elav>dcr2,atlRNAi flies (open circles) that had been maintained at 25°C as single mating pairs were analyzed for viability (blue and red circles) and paralysis (green circles). Mean±s.e.m. of the percentage of flies living, paralyzed or dead from seven replicates with 70 flies for Tork17004/+; elav>dcr2,atlRNAi and 73 flies for elav>dcr2,atlRNAi is shown. (B–I) Dissected thoracic tissue from 1-day-old (B–E) or 7-day-old (F–I) elav>dcr2,atlRNAi (B,D,F and H) or Tork17004/+;elav>dcr2,atlRNAi (C,E,G and I) adults was fixed and stained with Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin (B,C,F and G) or an anti-ubiquitin antibody (D,E,H and I). DFM49 was visualized. Scale bars: 25 µm. Each image is a single slice from a confocal z-stack. (J–K) 0-day-old (J) or 7-day-old (K) Tork17004/+;elav>dcr2,atlRNAi males (blue circles represent each individual animal DFM49) or elav>dcr2,atlRNAi males (green circles represent each individual animal DFM49) were dissected and analyzed. Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin staining was used to outline DFM49. (J) Quantification of polyubiquitin pixel intensities per µm3 in each muscle following staining with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. Means±s.e.m. are indicated. P=0.024 by Student's t-test for elav>dcr2,atlRNAi flies versus Tork17004/+;elav>dcr2,atlRNAi. (K) Quantification of actin levels by measuring Alexa-Fluor-647 pixel intensities per µm3 following staining with Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin. Means±s.e.m. are indicated. P=0.003 by Student's t-test for elav>dcr2,atlRNAi flies versus Tork17004/+;elav>dcr2,atlRNAi.

Increased reactive oxygen species generation and activation of the JNK–Foxo stress pathway in degenerating muscles

The sensitivity of locomotor behavior, viability and muscle phenotypes to Tor inhibition raised the possibility that muscle Tor is activated in neuronal atl-knockdown muscles. Because chronic Tor activation can increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in Drosophila (Lee et al., 2010), we questioned if neuronal atl knockdown or the atl2 null mutation also increased muscle ROS. When we labeled dissected thoracic muscles with the ROS indicator dihydroethidium (DHE), which oxidizes to ethidium in the presence of reactive oxygen, we found that both neuronal atl knockdown (Fig. 6A,B) and atl2 (Fig. 6C,D) significantly increased ethidium fluorescence and hence ROS generation in muscle compared to that in controls (P=0.025 and P=0.004, respectively, Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

atl loss triggers increased ROS generation and increased JNK and Foxo activity in muscle. All animals analyzed were males reared as mating pairs. (A–D) Live imaging of dissected thoracic tissue from elav>dcr2 (A) and elav>dcr2,atlRNAi (B), w1118 (C) and atl2 (D) adults immediately following eclosion (day 0) and treated with the ROS indicator dihydroethidium (DHE). DFM49 has been imaged. Scale bars: 25 µm. (A–D) Maximum intensity z-projections from a confocal z-stack. (E) Quantification of ethidium pixel intensity per µm3 of DFM49 in elav>Dcr2 (blue circles represent each individual data point), elav>Dcr2,atlRNAi (green circles represent each individual animal DFM49), w1118 (red circles represent each individual animal DFM49) and atl2 (cyan circles represent each individual animal DFM49). Means±s.e.m. are indicated. P=0.035 for elav>dcr2 versus elav>dcr2,atlRNAi, and P=0.004 for w1118 versus atl2. (F–I) Dissected thoracic tissue from elav>dcr2 (F), elav>dcr2,atlRNAi (G), w1118 (H) and atl2 (I) adults, each also expressing puc-lacZ, at 3 days following eclosion (F,G) or immediately following eclosion (H,I) and treated with an antibody against β-galactosidase. Scale bar: 25 µm. The images are maximum intensity z-projections from a confocal z-stack. (J–M) Dissected thoracic tissue from elav>dcr2 (J), elav>dcr2,atlRNAi (K), w1118 (L) and atl2 (M) adults, each also expressing 4E-BP-lacZ, immediately following eclosion and treated with an antibody against β-galactosidase. Scale bars: 25 µm. Images are maximum intensity z-projections from a confocal z-stack. An image that is representative of three animals is shown for each condition.

This increased ROS might contribute to muscle degeneration by promoting oxidative damage. In addition to promoting damage, however, ROS can act as a signaling molecule. Reactive oxygen increases expression of the anti-oxidants Catalase (Cat) and SOD1 by activating the MAP kinase JNK, which in turn phosphorylates and activates the transcription factor Foxo, which is a direct transcriptional activator of Cat and SOD1 (Essers et al., 2004; van den Berg et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2005). Thus, we asked whether atl loss activated muscle JNK and Foxo. To answer this question, we introduced two transcriptional reporters, the JNK-responsive puc-lacZ and the Foxo-responsive 4E-BP-lacZ (4E-BP is also known as Thor in flies), into neuronal atl-knockdown and atl2 adults as well as controls. For these transcriptional reporters, P elements expressing a nucleus-localized β-galactosidase construct were inserted into the JNK-activated puckered (puc) and Foxo-activated 4E-BP genes (Demontis and Perrimon, 2010; Owusu-Ansah et al., 2013). We found that in these adults, antibodies against β-galactosidase strongly labeled nuclei from neuronal atl-knockdown and atl2 flies, but not those from controls, for both puc-lacZ (Fig. 6F–I) and 4E-BP-lacZ constructs (Fig. 6J–M). Thus, degenerating muscles from adults that lack atl activate the JNK–Foxo stress pathway.

Muscle atl knockdown confers rapamycin-sensitive progressive locomotor deficits and muscle polyubiquitin-aggregate accumulation

atl2 adults exhibit phenotypes more extreme than those exhibited in neuronal atl-knockdown flies, including earlier onset and more severe locomotor defects, as well as a dwarf body size (Orso et al., 2009). These observations raise the possibility that atl acts in non-neuronal cells as well as neurons to control organismal function. In fact, atl loss from muscle has been previously reported to affect muscle microtubules and synaptic boutons (Lee et al., 2009). To test for a role for muscle atl in behavior and muscle physiology and anatomy, we drove atl RNAi expression with two muscle drivers, Mhc-Gal4 and Mef2-Gal4. We found phenotypes similar to, but not identical to, those upon neuronal atl knockdown. In particular, muscle atl knockdown conferred progressive age-dependent locomotor deficits (Fig. 7A; Fig. S3) that were accelerated by maintaining flies as part of a mating pair (Fig. S3). Mef2-Gal4-driven atl knockdown conferred even stronger locomotor phenotypes than Mhc-Gal4 (Fig. S3), most likely because Mef2-Gal4, but not Mhc-Gal4, is expressed strongly in larval muscle. Mhc>atlRNAi conferred no detectable muscle degeneration in either 3-day-old or 7-day-old adults (Fig. 7C–F,K–N) but conferred polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation in several prothoracic muscles in 3-day-old adults (Fig. 7G–J) and additionally in prothoracic sternal anterior rotator muscle 31 (muscle 31) in 7-day-old adults (Fig. 7O–R). The muscle groups most strongly affected by muscle atl knockdown were different from the muscle groups affected by neuronal atl knockdown. Thus, DFM49 did not exhibit degeneration upon muscle atl knockdown, whereas both DFM49 and muscle 31 did exhibit degeneration upon neuronal atl knockdown (Fig. 2; data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Knockdown of muscle atl triggers locomotor deficits and polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation. (A) Males of the indicated genotypes, maintained as mating pairs at 25°C, were analyzed for viability (red and blue circles) and paralysis (green circles). Mean±s.e.m. of the percentage of flies living, paralyzed or dead from three replicates (49 animals) of Mhc>Dcr2 flies (open circles) and three replicates (59 animals) of Mhc>Dcr2,atlRNAi flies (closed circles) is shown. (B) Anatomy of the adult prothorax. Dorsal view of the ventral half of the thorax, oriented anterior up (schematic adapted from Zalokar, 1947). Prothoracic sternal anterior rotator muscles (25, 26, 27, 31, and 33) are shown. Muscle 31 is highlighted and this muscle was imaged. (C–R) Low-magnification image of several thoracic muscles (C,D,G,H,K,L,O,P; scale bars: 50 µm) or high-magnification images of muscle 31 (E,F,I,J,M,N,Q,R; scale bars: 25 µm) taken from flies of the indicated genotypes either 3 days (C–J) or 7 days after eclosion (K–R). For C–F and K–N, muscles were stained with Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin. For G–J and O–R, muscles were stained with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. Images in C–R are maximum intensity z-projections from a confocal z-stack.

We analyzed the properties of muscle 31 in more detail. As shown in Fig. S4, 13-day-old Mhc>atlRNAi exhibited detectable loss of muscle Z-disc and actin structures (Fig. S4A–F), which became more evident in 17-day-old flies (Fig. S4G–L). Muscle degeneration, as measured by Alexa-Fluor-647–phalloidin staining intensity normalized to that in control, was significantly increased as Mhc>atlRNAi flies aged from 13 to 17 days old (Fig. S4M).

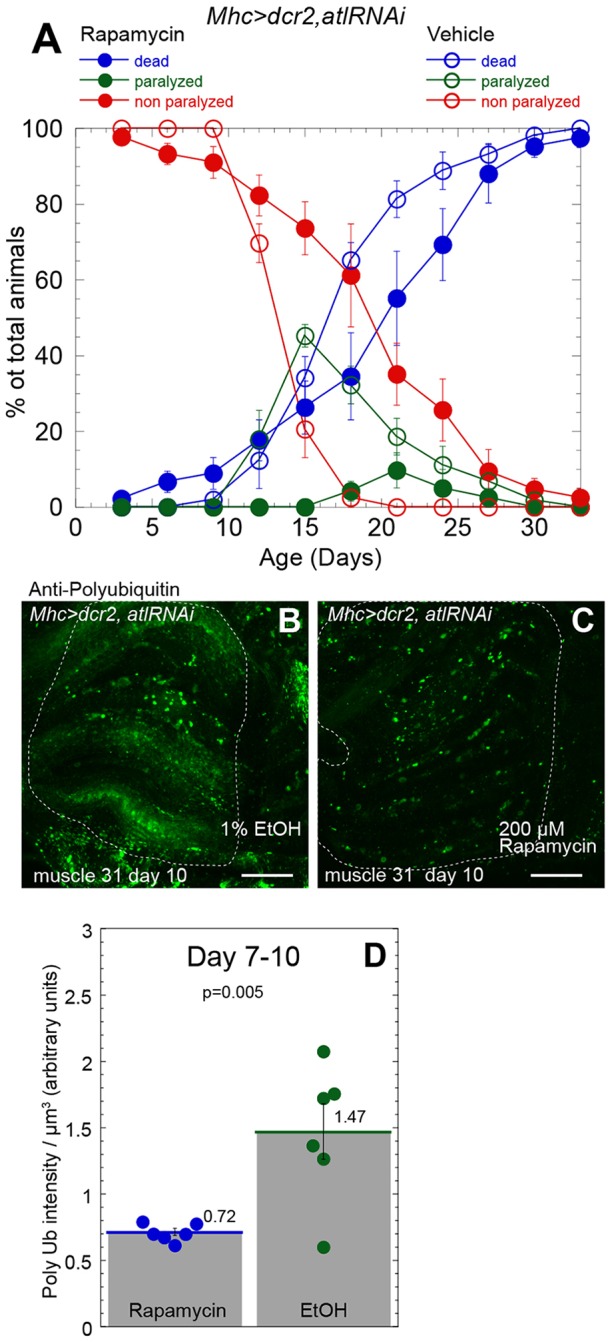

The similarity in phenotype between muscle and neuronal atl-knockdown flies raised the possibility that Tor pathway activity might be required for the muscle knockdown phenotypes, similar to that found for the neuronal knockdown phenotypes. To test this possibility, we administered 200 µM rapamycin to adults in which muscle atl had been knocked down, as described above. We found that rapamycin administration significantly delayed onset of paralysis (P<0.001, Fig. 8A; Fig. S1F) and increased lifespan (P=0.0489; Fig. S1E). In addition, rapamycin significantly decreased the intensity of staining of polyubiquitin aggregates (Fig. 8B–D). These results suggest that Tor activity is required for the effects of muscle atl knockdown on muscle structure and function.

Fig. 8.

Rapamycin administration partially suppresses locomotor and viability deficits and polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation conferred by muscle atl knockdown. All animals analyzed were males that had been reared as mating pairs. (A) Mhc>dcr2,atlRNAi flies, maintained at 25°C as single mating pairs, were fed with food containing 200 µM rapamycin (solid circles) or 1% EtOH vehicle (open circles) immediately following eclosion. Viability (blue and red circles) and paralysis (green circles) were measured. The means±s.e.m. of the percentage of flies living, paralyzed or dead from five replicates (40 animals) of Mhc>Dcr2, atlRNAi flies that had been treated with rapamycin and five replicates (41 animals) of Mhc>Dcr2,atlRNAi flies that had been treated with vehicle are shown. (B,C) Dissected thoracic tissue from 10-day-old Mhc>dcr2,atlRNAi adults that had been fed immediately following eclosion with either vehicle (1% EtOH, B) or 200 µM rapamycin (C) was fixed and stained with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. Coxal muscle 31 is outlined. Scale bars: 25 µm. Maximum intensity z-projections from a confocal z-stack are shown. (D) Quantification of polyubiquitin (Poly Ub)-staining pixel intensities per µm3 in each muscle from flies fed with rapamycin (blue circles) or vehicle (green circles) following staining with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. Images from 7- and 10-day-old flies were pooled. Means±s.e.m. are above each bar. P=0.005 by Student's t-test.

DISCUSSION

Cellular degeneration in a Drosophila HSP model

Degeneration of specific subsets of neurons is thought to underlie locomotor dysfunction in HSP (Fink, 2013), but the molecular and cellular mechanisms mediating this degeneration have not been elucidated. Here, we used the Drosophila system to identify and investigate the mechanisms underlying cellular degeneration caused by loss of atl. We found that RNAi-mediated atl knockdown either in muscles or neurons triggers progressive locomotor deficits accompanied by degeneration of specific muscles within the adult thorax. This degeneration is preceded by accumulation of aggregates containing polyubiquitin, which is a hallmark of degenerating neurons in diseases such as Alzheimer's, Huntington's and Parkinson's. In addition, muscles from neuronal atl knockdown and atl2 null mutants generated increased amounts of ROS and activated the JNK–Foxo stress pathway. Finally, we show that administering the Tor kinase inhibitor rapamycin attenuates the locomotor deficits and polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation caused by either neuronal or muscle atl knockdown. These results demonstrate that atl loss triggers cell degeneration through both cell autonomous and nonautonomous (presumably synaptic) means, thus providing new information on the mechanism underlying neurodegeneration that might be relevant to individuals affected by HSP. These results also pave the way for phenotypic studies on atl mutations identified in HSP individuals (Fink, 2014; Smith et al., 2009). Finally, these results raise the possibility that rapamycin administration might be therapeutic for the HSP.

Atl acts in a cell nonautonomous manner to control muscle degeneration and polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation

We showed that pan-neuronal atl knockdown causes degeneration and polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation within specific muscle groups within the adult thorax. Polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation can occur as a result of the expression of mutant misfolding proteins (Blokhuis et al., 2013), but this is unlikely to be the cause of the aggregate accumulation we observe because the muscle remains genetically wild-type when atl is knocked down in neurons. Polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation can also be caused by autophagy inhibition (Rubinsztein, 2006). We hypothesize that polyubiquitin accumulation results from muscle Tor activation because we observed that Tor inhibition, a known inhibitor of autophagy (Nedelsky et al., 2008), partially suppressed the locomotor and muscle phenotypes caused by neuronal atl knockdown. However, this hypothesis has yet to be rigorously tested.

How might neuronal atl knockdown activate muscle Tor? It has been previously shown that muscle Tor is activated in Drosophila larvae when synaptic transmission is attenuated by deleting one of two alternate subunits of the muscle glutamate receptor GluRII (Penney et al., 2012). We have recently shown that neuronal atl loss decreases evoked transmitter release from motor neurons (Summerville et al., 2016), suggesting that this decreased synaptic transmission is responsible for the muscle Tor activation. In this perspective, our observation that the locomotor and viability deficits are accelerated by expressing the TrpA1 channel raises the possibility that increasing the frequency of this sub-normal synaptic transmission further increases muscle Tor activation.

Atl acts in a cell-autonomous manner to control muscle degeneration and polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation

As is the case for neuronal atl knockdown, muscle atl knockdown also causes locomotor deficits and muscle polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation. The rapamycin sensitivity of these effects raises the possibility that muscle atl knockdown, similar to neuronal atl knockdown, activates muscle Tor. It is unknown how muscle Atl might regulate Tor activity in a cell-autonomous manner. However, as an ER fusion protein, Atl controls ER morphology, and atl loss disrupts ER morphology in multiple cell types (Orso et al., 2009; Summerville et al., 2016). Disruption of ER morphology within the muscle could alter localization and trafficking through the endocytic system of Tor-activating receptors such as the insulin receptor. This possibility is supported by the observation from several systems that atl loss activates bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) receptor signaling by altering receptor trafficking (Fassier et al., 2010; Zhao and Hedera, 2013). The recent report that ER tubules interact directly with endosomal structures, and indeed provide for sites of endosome fission as well as membrane protein trafficking (Rowland et al., 2014), indicates a possible mechanism for this effect on signaling. atl loss might also alter Tor endosomal location, which could affect Tor activity as Tor is known to be activated on specific endosomal compartments (Betz and Hall, 2013).

Role of ROS and the JNK–Foxo stress pathway in muscle physiology

Chronic Tor activation leads to increased ROS generation in Drosophila wing discs (Lee et al., 2010). We showed likewise that neuronal atl knockdown or atl2 increases muscle ROS generation. Increased ROS has a number of effects on cell physiology, some toxic and some protective. The ROS-dependent accumulation of oxidized and possibly dysfunctional DNA, protein and lipids inhibits cell function. It is possible that the increased ROS generation, particularly in combination with attenuated autophagy, is responsible at least in part for the muscle degeneration caused by atl loss. However, ROS can act as a signaling molecule that activates stress resistance pathways to mitigate the effects of increased ROS (Benhar et al., 2002). For example, ROS activates the stress kinase JNK by enabling activation of the JNK-activating kinase ASK1 (Liu et al., 2000). Activated JNK phosphorylates and activates the Foxo transcription factor (Essers et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2005), which in turn increases transcription of several stress resistance genes, including those that oppose the effects of Tor activation, such as autophagy genes, translational inhibitors such as 4E-BP, and anti-oxidant genes Catalase and SOD1 (Demontis and Perrimon, 2010; Essers et al., 2004). Therefore, a Tor-activated ROS increase, by activating JNK and Foxo, can act as a negative-feedback mechanism to oppose the effects of Tor activation. Our observation that atl loss activates both JNK and Foxo in muscle is consistent with the possibility that such a ROS–JNK–Foxo stress pathway acts in muscle as a consequence of atl loss.

Cellular degeneration and clinical features in HSP

Our results are relevant to HSP clinical features in two ways. First, locomotor deficits in HSP are believed to be associated with degeneration of specific subsets of neurons within the brain and spinal cord. Although the mechanisms underlying the neurodegeneration that is presumed to occur in HSPs are unknown, neurodegeneration in other disorders, such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and Huntington's diseases, appear to involve Tor activation (reviewed recently in Talboom et al., 2015) and appear to be sensitive to rapamycin administration. Our results support the notion that the degeneration in atl-mediated HSP might likewise be caused by Tor activation; if so, the development of this HSP would be placed within the same framework as the mechanisms underlying the other neurodegenerative disorders listed above. Second, our results demonstrate that atl loss confers muscle degeneration both in cell-autonomous and cell-nonautonomous (presumably by synaptic means) processes. These results raise the possibility that neurodegeneration in atl-mediated HSP likewise involves both cell autonomous and synaptic pathologies that might interact in complex ways.

We saw no obvious evidence of bulk neuronal loss in neuronal atl-knockdown adults. However, our analysis leaves open the possibility that specific subsets of neurons might degenerate. For example, Lee et al. (2008) have reported that adults bearing the partial loss-of-function atl1 exhibit specific degeneration of dopaminergic neurons. It would be of interest to determine whether atl knockdown in dopaminergic neurons leads to similar degeneration, and if so, whether this degeneration is accompanied by polyubiquitin aggregate accumulation and is sensitive to rapamycin.

Here, we describe effects of loss of only one HSP gene. It is possible that other HSP genes might behave in a similar way to atlastin. In Drosophila, orthologs of several HSP genes, including Reticulon (Rtnl1, SPG12), spastin (SPG4), spartin (SPG20) and spichthyin (SPG6) have been identified and analyzed previously (Lee et al., 2008; Nahm et al., 2013; O'Sullivan et al., 2012; Sherwood et al., 2004; Summerville et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2007). These studies have demonstrated that mutations or RNAi knockdown of any of these genes confer a remarkably uniform set of behavioral and nervous system phenotypes, including progressive age-dependent locomotor deficits, decreased evoked neurotransmitter release from larval motor nerve terminals, increases in retrograde (muscle to neuron) signaling mediated by a ligand of the BMP family and increases in the number of synaptic boutons at the larval neuromuscular junction (note that not all phenotypes have been reported for all genes listed). Given these similarities, it is possible that loss of these genes might also result in novel phenotypes similar to those upon atl loss that we report here, particularly rapamycin sensitivity of locomotor deficits. If so, and if these features are recapitulated in humans, then our studies on mechanisms underlying behavioral and cellular phenotypes in Drosophila atlastin might have broad applications for HSP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila stocks and media

The following lines were obtained from the Drosophila Stock Center at Bloomington, Indiana University, IN: w1118 (#3605), Tork17004/CyO (#11218), Zasp66-zcl0663 (#6824), 4E-BP-lacZ (#9558) and puc-lacZ (#11173). UAS-TrpA1 was a generous gift from Dr Gregg Roman (University of Houston, Houston, TX). All other stocks used have been reported previously (Summerville et al., 2016).

Drosophila carrying atl2 or UAS-TrpA1 were maintained on the following media: 62 g/l corn syrup, 8.67 g/l soybean flour, 63.3 g/l cornmeal, 15 g/l yeast, 5 g/l agar and 4.18 ml/l propionic acid. All other stocks were maintained long-term on standard medium at 18°C under 70% humidity. All experiments were performed on Drosophila that had been reared and maintained at 25°C with a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle unless otherwise indicated.

Construction of flies bearing UAS-atlDeOp

pJM1095 (pUASTattB-MYC) was generated as an intermediate clone to add a Myc tag to atlastin. It was constructed by generating a double-stranded oligonucleotide [5′-phosphorylated oligonucleotides BglII-AgeI-Kozak-MYC-BamHI top (5ʹ-GATCTACCGGTCAAAATGGAACAAAAACTCATCTCAGAAGAGGATCTGG-3ʹ) and BglII-AgeI-Kozak-MYC-BamHI bottom (5ʹ-GATCCCAGATCCTCTTCTGAGATGAGTTTTTGTTCCATTTTGACCGGTA-3ʹ)] that was ligated into pUASTattB cut with BamHI. pUASTattB (Bischof et al., 2007) was provided by Konrad Basler (University of Zürich, Institute of Molecular Life Sciences, Zürich, Switzerland). pJM1090 (pUASTattB-MYC-atlDe-OP) expresses a codon-deoptimized Atl protein (atlDe-OP). A 1630-bp synthetic Drosophila atl gene was optimized for expression in Escherichia coli (therefore deoptimizing expression in Drosophila) by Genescript and purchased in the pUC57 plasmid. The atlDe-OP cDNA cassette was amplified using PCR with the oligonucleotides BamHI-Opt-Datl (5ʹ-GTGGATCCATGGGTGGTTCGG-3ʹ) and Opt-Datl-KpnI (5ʹ-CGGTACCTCAGGAGGGTTTCAC-3ʹ), cut by BamHI and KpnI, and ligated into pJM1095 (pUASTattB-MYC) that had been cut with the same enzymes resulting in a Myc tag at the N-terminus of the Drosophila codon-deoptimized Atl protein.

Drosophila stock construction

pJM1090 DNA was injected into VK37 embryos at Genetivision (Houston, TX). Injected flies were backcrossed seven times to w1118 flies, and stocks carrying insertions on chromosome two (VK37) were established. The expression of atlDe-OP was confirmed by the evidence that an anti-Myc antibody stained fly brains in which UAS-MYC- atlDe-OP was driven by elav-Gal4.

Paralysis and lifespan determination

Adult males were collected under light CO2 anesthesia within 24 h of eclosion and maintained either alone or with a single female. Every 2 to 3 days, males were analyzed for locomotor behavior (paralysis) and viability. To check the paralysis, each vial was placed horizontally and tapped gently to encourage the animal to stand on the wall of the vial. The vial was then placed vertically. If the animal fell down or did not climb within 15 s, it was considered paralyzed. Each vial was replaced every 10–12 days for vials containing single males, and every 6–7 days for vials containing mating pairs. For statistical purposes, data for lifespan and locomotor determination involving single males were pooled before plotting, whereas for males aged as mating pairs, the sample size (n) for lifespan and locomotor determination was given by the number of replicate vials.

For locomotor behavior and viability experiments involving UAS-TrpA1 and controls, flies were collected within 24 h of eclosion, maintained at 22°C for 24 h and then switched to 28.5°C with continuous light. Locomotor behavior and viability were assessed daily as described above.

Immunocytochemistry

All control and experimental animals were processed and imaged on the same day. Flies were pinned in PBS on 35-mm Petri dish lids filled with Sylgard 184 (Electron Microscopy Sciences). One side of the thoracic cuticle surrounding the wing hinge was removed from the remainder of the body. This cuticle piece was held by fine forceps while the indirect flight muscles, jumping muscle M66 and trachea were removed with forceps or a tungsten needle (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA, catalog #10130-05) to expose DFM49. For experimental-group flies, the wings were removed completely, whereas for flies in the control group, about one-third of the wings was retained to mark genotype and to enable thoracic muscles of each group to be treated together. Following removal of PBS, thoraxes were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 10 min, then washed in PBS with 0.5% Tween-20 (PBS-T) three times for 20 min each, and finally blocked by a 30-min incubation with 5% normal goat serum (NGS, 005-000-121, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Samples were incubated overnight with gentle orbital shaking at 4°C with primary antibody, washed three times for 20 min each with PBS-T and then incubated overnight at 4°C with secondary antibody. Samples were then washed with PBS and mounted in mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, catalog # H-1200) containing DAPI.

For double staining of Discs large (dlg) and Bruchpilot (brp), samples were incubated overnight with gentle orbital shaking at 4°C with the antibody against brp, washed three times for 20 min each with PBS-T, and then incubated for 2 h at 23°C with a goat anti-mouse Fab fragment conjugated with Alexa-Fluor-488. Finally, samples were incubated overnight at 4°C with a mouse antibody against dlg, washed three times for 20 min each with PBS-T and then incubated for 2 h at 23°C with a goat anti-mouse IgG antibody coupled with Texas Red.

The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-dlg (1:200, 4F3) and mouse anti-brp (nc82, 1:50) antibodies were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; mouse anti-polyubiquitin antibody (1:1000, BML-PW8810-0100) was obtained from Enzo Life Science; mouse anti-β-galactosidase (1:400, Z378A) was obtained from Promega; Alexa-Flour-647–phalloidin (1:400, A22287) was obtained from Invitrogen; and cellTracker DiI (1:1000, C7001) was obtained from Life Technologies. The following secondary antibodies were used: goat anti-mouse IgG antibody coupled with Alexa-Fluor-488 (Molecular Probes, A11029); goat anti-mouse Fab Fragment coupled with Alexa-Fluor-488 (547-003) and goat anti-HRP conjugated to Alexa 647 (123-605-021), (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories); and goat anti-mouse IgG coupled with Texas Red (510-1902, Rockland Immunochemicals). All images, both live and fixed, were acquired on a Nikon A1-Rsi confocal microscope.

Live imaging and ROS analysis

Live imaging was performed to analyze ROS. Flies were pinned in HL6 solution (Macleod et al., 2002), and thoracic muscles were dissected as described above. Following exposure of DFM49, samples were incubated in 60 µM dihydroethidium (10057, Biotium, Hayward) in the dark for 5 min and then placed interior-side down into a drop of HL6 in the center of a 35-mm glass-bottomed dish (P35G-0-20-C, MatTek). After placement of a cover slip, DFM49 was imaged on an inverted confocal microscope (Nikon, model A1-Rsi) with a 60× (1.40 numeric aperture) oil immersion objective. Ethidium was excited with a 543-nm helium-neon laser, and light emitted between 552 and 691 nm was collected. Each DFM49 sample was scanned from the top surface to a depth of 25 µm.

Rapamycin administration

Rapamycin (LC Laboratories, catalog # R-5000) was dissolved in the absolute ethanol vehicle at a 20 mM concentration. To introduce rapamycin or vehicle into the medium, one volume of stock solution or absolute ethanol was mixed in a mortar with 100 volumes of Drosophila medium. 2–3 ml of the food was then divided into vials. Adult males, collected within 24 h of eclosion, were maintained with a single female at 25°C. Males were assessed for paralysis and viability every 2–3 days. Flies were introduced into fresh medium every 6–7 days.

Image quantification and statistical analysis

Regions of interest were manually drawn using Imaris 8 software (Bitplane, South Windsor, CT) to include the entire DFM49. Pixel intensities and volumes within each sample were extracted, and mean intensities were calculated by dividing overall pixel intensity by the DFM49 volume. Student's t-test was used for pairwise comparisons of significance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the various members of the Drosophila community, as well as the Bloomington Stock Center for providing fly lines. We would also like to thank Weiwei Zhong for the use of her video microscopy system; Joseph Faust and James Summerville for helpful suggestions; Gregg Roman for the kind gift of flies bearing UAS-TrpA1; Miguel Betancourt-Solis for assistance in Drosophila media preparation and disposal; and Greg Gaskey, Rishi Sinha, Danning Hu, Ethan Fan, Winifred Tang, Alvin Sheng and Calvin Su for assistance in analysis of Drosophila locomotor behavior and viability.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, S.X., M.S. and J.A.M; Methodology, S.X.; Investigation, S.X.; Writing – original draft, M.S. and J.A.M.; Writing – review & editing, S.X., M.S. and J.A.M.; Funding acquisition, M.S. and J.A.M.; Project administration, M.S. and J.A.M.

Funding

J.A.M. is supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM101377). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.196741.supplemental

References

- Alves-Rodrigues A., Gregori L. and Figueiredo-Pereira M. E. (1998). Ubiquitin, cellular inclusions and their role in neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci. 21, 516-520. 10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01276-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhar M., Engelberg D. and Levitzki A. (2002). ROS, stress-activated kinases and stress signaling in cancer. EMBO Rep. 3, 420-425. 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz C. and Hall M. N. (2013). Where is mTOR and what is it doing there? J. Cell Biol. 203, 563-574. 10.1083/jcb.201306041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof J., Maeda R. K., Hediger M., Karch F. and Basler K. (2007). An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3312-3317. 10.1073/pnas.0611511104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjedov I., Toivonen J. M., Kerr F., Slack C., Jacobson J., Foley A. and Partridge L. (2010). Mechanisms of life span extension by rapamycin in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 11, 35-46. 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokhuis A. M., Groen E. J. N., Koppers M., van den Berg L. H. and Pasterkamp R. J. (2013). Protein aggregation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 125, 777-794. 10.1007/s00401-013-1125-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bové J., Martínez-Vicente M. and Vila M. (2011). Fighting neurodegeneration with rapamycin: mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 437-452. 10.1038/nrn3068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijn L. I., Houseweart M. K., Kato S., Anderson K. L., Anderson S. D., Ohama E., Reaume A. G., Scott R. W. and Cleveland D. W. (1998). Aggregation and motor neuron toxicity of an ALS-linked SOD1 mutant independent from wild-type SOD1. Science 281, 1851-1854. 10.1126/science.281.5384.1851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demontis F. and Perrimon N. (2010). FOXO/4E-BP signaling in Drosophila muscles regulates organism-wide proteostasis during aging. Cell 143, 813-825. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essers M. A. G., Weijzen S., de Vries-Smits A. M. M., Saarloos I., de Ruiter N. D., Bos J. L. and Burgering B. M. T. (2004). FOXO transcription factor activation by oxidative stress mediated by the small GTPase Ral and JNK. EMBO J. 23, 4802-4812. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassier C., Hutt J. A., Scholpp S., Lumsden A., Giros B., Nothias F., Schneider-Maunoury S., Houart C. and Hazan J. (2010). Zebrafish atlastin controls motility and spinal motor axon architecture via inhibition of the BMP pathway. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1380-1387. 10.1038/nn.2662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink J. K. (2013). Hereditary spastic paraplegia: clinico-pathologic features and emerging molecular mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 126, 307-328. 10.1007/s00401-013-1115-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink J. K. (2014). Hereditary spastic paraplegia: clinical principles and genetic advances. Semin. Neurol. 34, 293-305. 10.1055/s-0034-1386767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floto R. A., Sarkar S., Perlstein E. O., Kampmann B., Schreiber S. L. and Rubinsztein D. C. (2007). Small molecule enhancers of rapamycin-induced TOR inhibition promote autophagy, reduce toxicity in Huntington's disease models and enhance killing of mycobacteria by macrophages. Autophagy 3, 620-622. 10.4161/auto.4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frake R. A., Ricketts T., Menzies F. M. and Rubinsztein D. C. (2015). Autophagy and neurodegeneration. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 65-74. 10.1172/JCI73944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q. and Figueiredo-Pereira M. E. (2010). Ubiquitin/proteasome pathway impairment in neurodegeneration: therapeutic implications. Apoptosis 15, 1292-1311. 10.1007/s10495-010-0466-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung C. H., Ro S.-H., Cao J., Otto N. M. and Kim D.-H. (2010). mTOR regulation of autophagy. FEBS Lett. 584, 1287-1295. 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kundu M., Viollet B. and Guan K.-L. (2011). AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 132-141. 10.1038/ncb2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King D. G. and Tanouye M. A. (1983). Anatomy of motor axons to direct flight muscles in Drosophila. J. Exp. Biol. 105, 231-239. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M., Waguri S., Chiba T., Murata S., Iwata J., Tanida I., Ueno T., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E. et al. (2006). Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature 441, 880-884. 10.1038/nature04723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M., Waguri S., Koike M., Sou Y.-S., Ueno T., Hara T., Mizushima N., Iwata J.-I., Ezaki J., Murata S. et al. (2007). Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell 131, 1149-1163. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Paik D., Bang S., Kang J., Chun B., Lee S., Bae E., Chung J. and Kim J. (2008). Loss of spastic paraplegia gene atlastin induces age-dependent death of dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila. Neurobiol. Aging 29, 84-94. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M., Paik S. K., Lee M.-J., Kim Y.-J., Kim S., Nahm M., Oh S.-J., Kim H.-M., Yim J., Lee C. J. et al. (2009). Drosophila Atlastin regulates the stability of muscle microtubules and is required for synapse development. Dev. Biol. 330, 250-262. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Budanov A. V., Park E. J., Birse R., Kim T. E., Perkins G. A., Ocorr K., Ellisman M. H., Bodmer R., Bier E. et al. (2010). Sestrin as a feedback inhibitor of TOR that prevents age-related pathologies. Science 327, 1223-1228. 10.1126/science.1182228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Nishitoh H., Ichijo H. and Kyriakis J. M. (2000). Activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) by tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2 requires prior dissociation of the ASK1 inhibitor thioredoxin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 2198-2208. 10.1128/MCB.20.6.2198-2208.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod G. T., Hegstrom-Wojtowicz M., Charlton M. P. and Atwood H. L. (2002). Fast calcium signals in Drosophila motor neuron terminals. J. Neurophysiol. 88, 2659-2663. 10.1152/jn.00515.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeo F., Eisenberg T. and Kroemer G. (2009). Autophagy for the avoidance of neurodegeneration. Genes Dev. 23, 2253-2259. 10.1101/gad.1858009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies F. M., Fleming A. and Rubinsztein D. C. (2015). Compromised autophagy and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 345-357. 10.1038/nrn3961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger S., Saukko M., Van Che H., Tong L., Puder Y., Riess O. and Nguyen H. P. (2010). Age at onset in Huntington's disease is modified by the autophagy pathway: implication of the V471A polymorphism in Atg7. Hum. Genet. 128, 453-459. 10.1007/s00439-010-0873-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahm M., Lee M.-J., Parkinson W., Lee M., Kim H., Kim Y.-J., Kim S., Cho Y. S., Min B.-M., Bae Y. C. et al. (2013). Spartin regulates synaptic growth and neuronal survival by inhibiting BMP-mediated microtubule stabilization. Neuron 77, 680-695. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedelsky N. B., Todd P. K. and Taylor J. P. (2008). Autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system: collaborators in neuroprotection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1782, 691-699. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orso G., Pendin D., Liu S., Tosetto J., Moss T. J., Faust J. E., Micaroni M., Egorova A., Martinuzzi A., McNew J. A. et al. (2009). Homotypic fusion of ER membranes requires the dynamin-like GTPase atlastin. Nature 460, 978-983. 10.1038/nature08280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan N. C., Jahn T. R., Reid E. and O'Kane C. J. (2012). Reticulon-like-1, the Drosophila orthologue of the Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia gene reticulon 2, is required for organization of endoplasmic reticulum and of distal motor axons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 3356-3365. 10.1093/hmg/dds167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Ansah E., Song W. and Perrimon N. (2013). Muscle mitohormesis promotes longevity via systemic repression of insulin signaling. Cell 155, 699-712. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y., Robinett C. C. and Baker B. S. (2011). Turning males on: activation of male courtship behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 6, e21144 10.1371/journal.pone.0021144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey U. B., Nie Z., Batlevi Y., McCray B. A., Ritson G. P., Nedelsky N. B., Schwartz S. L., DiProspero N. A., Knight M. A., Schuldiner O. et al. (2007). HDAC6 rescues neurodegeneration and provides an essential link between autophagy and the UPS. Nature 447, 859-864. 10.1038/nature05853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei J.-J. and Hugon J. (2008). mTOR-dependent signalling in Alzheimer's disease. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 12, 2525-2532. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00509.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penney J., Tsurudome K., Liao E. H., Elazzouzi F., Livingstone M., Gonzalez M., Sonenberg N. and Haghighi A. P. (2012). TOR is required for the retrograde regulation of synaptic homeostasis at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Neuron 74, 166-178. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B., Vacher C., Berger Z., Davies J. E., Luo S., Oroz L. G., Scaravilli F., Easton D. F., Duden R., O'Kane C. J. et al. (2004). Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nat. Genet. 36, 585-595. 10.1038/ng1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland A. A., Chitwood P. J., Phillips M. J. and Voeltz G. K. (2014). ER contact sites define the position and timing of endosome fission. Cell 159, 1027-1041. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein D. C. (2006). The roles of intracellular protein-degradation pathways in neurodegeneration. Nature 443, 780-786. 10.1038/nature05291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood N. T., Sun Q., Xue M., Zhang B. and Zinn K. (2004). Drosophila spastin regulates synaptic microtubule networks and is required for normal motor function. PLoS Biol. 2, e429 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. N., Bevan S., Vance C., Renwick P., Wilkinson P., Proukakis C., Squitieri F., Berardelli A., Warner T. T., Reid E. et al. (2009). Four novel SPG3A/atlastin mutations identified in autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia kindreds with intra-familial variability in age of onset and complex phenotype. Clin. Genet. 75, 485-489. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01184.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder H., Mensah K., Theisler C., Lee J., Matouschek A. and Wolozin B. (2003). Aggregated and monomeric alpha-synuclein bind to the S6′ proteasomal protein and inhibit proteasomal function. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11753-11759. 10.1074/jbc.M208641200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerville J. B., Faust J. F., Fan E., Pendin D., Daga A., Formella J., Stern M. and McNew J. A. (2016). The effects of ER morphology on synaptic structure and function in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Sci. 129, 1635-1648. 10.1242/jcs.184929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talboom J. S., Velazquez R. and Oddo S. (2015). The mammalian target of rapamycin at the crossroad between cognitive aging and Alzheimer's disease. Npj Aging Mech. Dis. 1, 15008 10.1038/npjamd.2015.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg M. C. W., van Gogh I. J. A., Smits A. M. M., van Triest M., Dansen T. B., Visscher M., Polderman P. E., Vliem M. J., Rehmann H. and Burgering B. M. T. (2013). The small GTPase RALA controls c-Jun N-terminal kinase-mediated FOXO activation by regulation of a JIP1 scaffold complex. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 21729-21741. 10.1074/jbc.M113.463885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vantaggiato C., Clementi E. and Bassi M. T. (2014). ZFYVE26/SPASTIZIN: a close link between complicated hereditary spastic paraparesis and autophagy. Autophagy 10, 374-375. 10.4161/auto.27173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. C., Bohmann D. and Jasper H. (2005). JNK extends life span and limits growth by antagonizing cellular and organism-wide responses to insulin signaling. Cell 121, 115-125. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Shaw W. R., Tsang H. T. H., Reid E. and O'Kane C. J. (2007). Drosophila spichthyin inhibits BMP signaling and regulates synaptic growth and axonal microtubules. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 177-185. 10.1038/nn1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M. (2013). Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways in neurological diseases. Biomed. J. 36, 40-50. 10.4103/2319-4170.110365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J.-Q., Yuan Y.-H., Gao Y.-N., Huang J.-Y., Ma K.-L., Gao Y., Zhang W.-Q., Guo X.-F. and Chen N.-H. (2014). Overexpression of human E46K mutant alpha-synuclein impairs macroautophagy via inactivation of JNK1-Bcl-2 pathway. Mol. Neurobiol. 50, 685-701. 10.1007/s12035-014-8738-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao T.-P. (2010). The role of ubiquitin in autophagy-dependent protein aggregate processing. Genes Cancer 1, 779-786. 10.1177/1947601910383277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalokar M. (1947). Anatomie du thorax de Drosophila melanogaster. Rev. Suisse Zool. 54, 17-53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Stallock J. P., Ng J. C., Reinhard C. and Neufeld T. P. (2000). Regulation of cellular growth by the Drosophila target of rapamycin dTOR. Genes Dev. 14, 2712-2724. 10.1101/gad.835000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. and Hedera P. (2013). Hereditary spastic paraplegia-causing mutations in atlastin-1 interfere with BMPRII trafficking. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 52, 87-96. 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]