Abstract

We describe a 62-year-old woman who presented with a history of ataxia, dizziness and urinary urgency. Neurological examination disclosed a positive Romberg sign, ataxia and postural instability. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed Chiari type 1 malformation (CM1). Forty-eight months later, the patient was clinically improved and underwent a second MRI examination, which showed complete resolution of the Chiari 1 malformation. Spontaneous resolution of CM1 is exceptionally rare and has to be considered in the radiological and clinical management.

Keywords: Chiari type 1 malformation, spontaneous resolution, cranial posterior fossa, tonsillar descent

Introduction

The term Chiari Malformation Type 1 (CM1) is used to indicate chronic cerebellar tonsillar descent. The estimated prevalence of CM1 is 0.6-1% in the general population and up to 3.6% in children1. A retrospective study of brain MRI at a tertiary care over a 43-month period found that 0.77% of the patients were found to have Chiari malformation2.

CM1 is characterized by underdevelopment and overcrowding of the posterior cranial fossa; it may be associated with neurological dysfunction secondary to hindbrain compression and hydro syringomyelia.

The current gold standard for the diagnosis is the finding of tonsillar descent on sagittal MRI3. It is generally accepted that downward displacement of the cerebellar tonsils by less than 2 mm can be considered normal2,4,5. Tonsillar herniation between 3 and 5 mm is indeterminate, and herniation of more than 5 mm is compatible with a CM1. Both tonsils are usually involved, but a unilateral tonsillar ectopia may occasionally be found.

Chiari 1 malformation may be asymptomatic or associated with neurological symptoms, such as headache, dizziness, ataxia and dysphagia; the degree of tonsillar herniation directly correlates with the severity of symptoms2,4,6. A spontaneous decrease or even complete resolution of the tonsillar herniation have exceptionally been reported7-10.

Case Report

A 62-year-old woman presented with a four-year history of ataxia, dizziness and urinary urgency. No previous skull trauma, neurosurgical operation or lumbar punctures were referred. Neurological examination showed a positive Romberg sign, ataxia and postural instability.

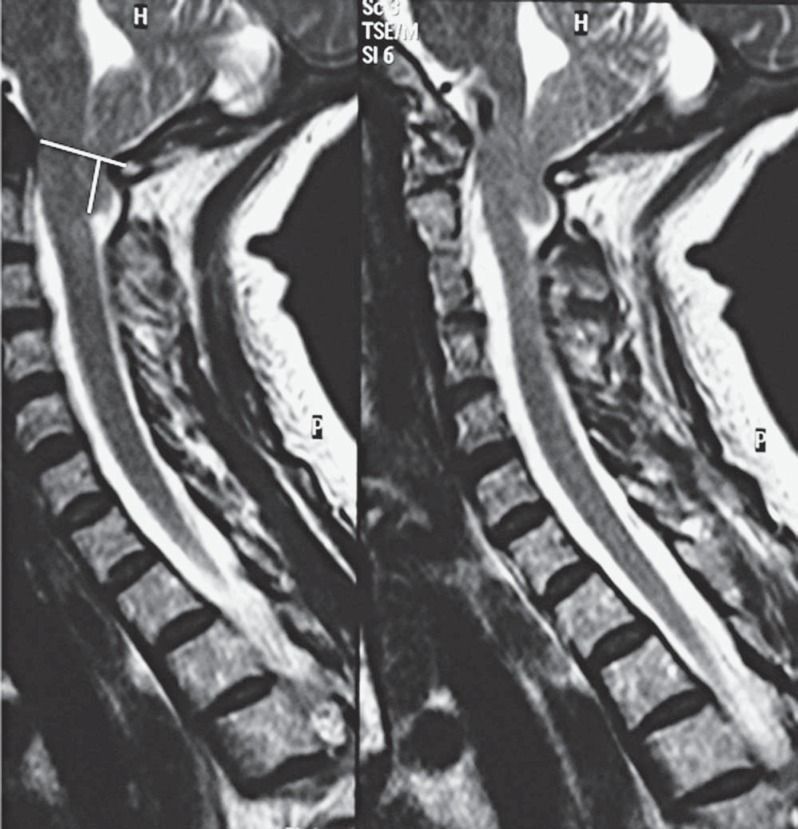

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1) showed Chiari malformation type 1 (CM1) with both cerebellar tonsils at the lower margin of C1. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) spaces at the region of the foramen magnum were obliterated. No hydrocephalus or syringomyelia were observed and there was no edema or signs of increased intracranial pressure.

Figure 1.

TSE T2 sagittal MRI shows a typical type 1 Chiari malformation. Cerebellar tonsils at the lower margin of C1. McRae's line shows tonsillar herniation.

From the clinical and neurological findings, the surgical decompression of the suboccipital posterior C1 was decided. However, the patient refused the surgical procedure. Some months after the observation, the neurological symptoms began to improve, then regressed. Forty-eight months after the first MRI study, the patient was observed again. Neurological examination showed no ataxia and no other neurological symptoms and signs. An MRI study showed complete resolution of the Chiari malformation with both cerebellar tonsils being returned to their normal position within the posterior cranial fossa (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

TSE T2 sagittal MRI shows spontaneous resolution of Chiari type 1 malformation. Cerebellar tonsils are in the posterior cerebellar fossa (PCF).

Discussion

In recent years, the wide availability of MRI has resulted in increasing numbers of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients harboring a Chiari I complex. The imaging study of the craniovertebral junction is complex. The skull-base lines, namely Chamberlain's, McGre-gor's, and McRae's lines are the standard reference tools used for defining skull-base anatomy, and follow-up of craniocervical pathology.

Chamberlain's line is the line from the roof of the hard palate to the posterior lip of the foramen magnum. In normal cases the odontoid process should be 3.3 mm around this line. McGregor's line extends from roof of hard palate to the most caudal portion of the occipital bone. McRae's line is the foramen magnum line drawn from the anterior margin of the foramen magnum (basion) to the posterior border (opisthion)11. Using McRae's line in our case, the cerebellar tonsils exceeded the line by a distance of about 12 mm.

The natural history of Chiari type 1 malformation is variable and not completely known. So predicting the evolution of these patients is important for management decisions. Most patients remain asymptomatic for many years and even throughout their lives. However, some investigators believe that in many cases the degree of tonsillar ectopia gradually increases with time and is associated with a likelihood of becoming symptomatic1.

Spontaneous improvement of Chiari Type 1 malformation and syringomyelia associated with variable clinical improvement has sometimes been reported12-15. Sudo et al. found an improvement in four out of 19 patients treated conservatively with periodical follow-up radiological studies. Besides, periodical variations of the degree and level of tonsillar herniation may also be documented.

Spontaneous complete resolution of a Chiari Type 1 malformation is a rarer event, mainly reported in children7,8. The increase in the volume of the posterior fossa that occurs with growth16,17 results in relative ascent of the cerebellar tonsils in their normal position8,18 and may explain the spontaneous resolution of the Chiari malformation sometimes observed in infancy and childhood.

In adult patients the complete resolution of a Chiari 1 malformation is exceptional, with only four well documented cases9,10,19,20 (Table 1). All patients were young (under 40-years except for ours) and asymptomatic. All had descent of both cerebellar tonsils up to C1 and all except ours had an associated syringomyelia. The time interval of the follow-up ranged between 32 and 48 months. All patients had complete resolution of the Chiari malformation and initial neurological symptoms; the associated syringomyelia disappeared in three cases and significantly improved in one. In three cases the clinical and radiological remission was observed to coincide with several favouring conditions resulting in changes in CSF pressure. Our case differs from the others reported cases for the older patient age, the absence of favouring conditions and the absence of associated syringomyelia.

Table 1.

Summary of reported cases of complete resolution of Chiari Type 1 malformation in adults.

| N. cases | Authors/ Years | Age/ Sex | Neurological symptoms | Degree of tonsillar herniation | Associated syringomyelia | Follow-up of syringomyelia | Interval time | Favouring conditions | Tonsillar herniation at follow-up | Neurological symptoms at follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Klekamp et al., 2001 | 37y/F | Yes | Up to C1 | Yes | Resolution | 32 months | None | Resolution | Asymtomatic |

| 2 | Coppa et al., 2006 | 27y/F | NA | Up to C1 | Yes | Resolution | NA | CSF otorrhea | Resolution | NA |

| 3 | Miele at al., 2012 | 36y/F | Yes | Up to C1 | Yes | Resolution | 48 months | Supratentorial craniotomy for cavernoma | Resolution | NA |

| 4 | Muthukumar and Christopher, 2013 | 24y/F | Yes | Up to C1 | Yes | Significant improvement | 36 months | Normal vaginal delivery | Resolution | Asymtomatic |

| 5 | Present report | 62y/F | Yes | Up to C1 | No | NA | 48 months | None | Resolution | Asymtomatic |

NA: not applicable.

Several theories have been postulated to explain the spontaneous resolution of Chiari 1 malformation in adults. These include atrophy of the cerebellar tonsils21, variations of the position of the cerebellar tonsils with advancing age16, physiological pressure changes in the intracranial and intraspinal compartments during normal delivery with restoration of normal CSF flow10,20, spontaneous restoration of normal CSF flow at the foramen magnum due to spontaneous disruption of the arachnoid scarring during labour and efforts9,15.

In three reported cases (Table 1) several favouring conditions resulting in changes in CSF pressure, such as otorrhea, supratentorial craniotomy and normal vaginal delivery, were referred. We did not find any evident favouring condition in our case.

Patients with spontaneous resolution of the Chiari malformation should be followed up with long-term MM studies as recurrence of the anomaly after resolution has been reported8.

The best management of Chiari 1 malformation is controversial. Asymptomatic tonsillar ectopia is usually not treated. In patients with significant symptoms, particularly if progressive, a sub-occipital-posterior C1 decompression is indicated. However, in adult patients with initial and stable neurological symptoms the management decision (surgery versus ob-servation) must be weighed also considering the possible, although rare, occurrence of complete resolution.

Conclusion

Complete clinical and neuroradiological resolution is an exceptional event which may occur in the natural history of Chiari 1 malformation, as a result of spontaneous restoration of CSF flow at the level of the foramen magnum. This event, although very rare, should be considered in management decision-making.

References

- 1.Osborn AG. Osborn's Brain: Imaging, Pathology, and Anatomy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. P. 1060–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meadows J Kraut M Guarnieri M et al. Asymptomatic Chiari Type I malformation identified on magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosurg. 2000; 92: 920–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urbizu A Poca MA Vidal X et al. MRI-based morphometric analysis of posterior cranial fossa in the diagnosis of Chiari malformation type I. J Neuroimaging. 2013; 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Barkovich AJ Wippold FJ Sherman JL et al. Significance of cerebellar tonsillar position on MR. Am J Neuroradiol. 1986; 7: 795–799. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alperin N Sivaramakrishnan A Lichtor T. Magnetic resonance imaging-based measurements of cerobrospinal fluid and blood flow as indicators of intracranial compliance in patients with Chiari malformation. J Neurosurg. 2005; 103: 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elster AD Chen MYM. Chiari I malformation: clinical and radiological reappraisal. Radiology. 1992; 183: 347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castillo M Douglas Wilson J. Spontaneous resolution of a Chiari I malformation: MR demonstration. Am J Neuroradiol. 1995; 16: 1158–1160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun JC Steinbok P Cochrane DD. Spontaneous resolution and recurrence of a Chiari I malformation and associated syringomyelia. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2000; 92: 207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klekamp J Iaconetta G Samii M. Spontaneous resolution of Chiari I malformation and syringomyelia: case report and review of literature. Neurosurgery. 2001: 53: 762–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muthukumar N Christopher J. Spontaneous resolution of Chiari I malformation and associated syringomylelia following parturition. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2013. DOI 10.1007/s00701-013-1620-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Cronin CG Lohan DG Mhuirchearrtigh JN et al. CT evaluation of Chamberlain's, McGregor's and McRae's skull-base lines. Clin Radiol. 2009; 64: 64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliviero WC Dinh DH. Chiari 1 malformation with traumatic syringomyelia and spontaneous resolution: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1992; 30: 758–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierallini A Ferone E Colonnese C. Magnetic resonace imaging of a case of spontaneous resolution of syrin-gomielia associated with type 1 Chiari malformation. Radiol. Med. 1997; 93: 621–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sudo K Tashiro K Miyasaka K. Features of spontaneous improvement in syringomyelia with low-situated cerebellar tonsils. Acta Neurol Belg. 1998; 98: 342–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kyoshima K Bogdanov EI. Spontaneous resolution of syringomyelia: report of two cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2003; 53: 762–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikulis DJ Diaz O Egglin TK et al. Variance of the position of the cerebellar tonsils with age: preliminary report. Radiology. 1992; 183: 725–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milhorat TH Nishikawa M Kula RW et al. Mechanisms of cerebellar tonsil herniation in patients with Chiari malformation as guide to clinical management. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010; 152: 1117–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raz N Gunning-Dixon F Head D et al. Age and sex difference in the cerebellum and the ventral pons: a prospective MR study of healthy adults. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001; 22: 1161–1167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coppa ND Kim HJ McGrail KM. Spontaneous resolution of syringomyelia and Chiari malformation type I in a patient with cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2006; 105: 769–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miele WR Schirmer CM Tao KC et al. Spontaneous resolution of a Chiari malformation Type I and syrinx after supratentorial craniotomy for excision of a cavernous malformation. J Neurosurg. 2012; 116; 1054–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deniz FE Oskuz E. Spontaneous syringomyelia resolution at an adult Chiari Type I malformation. Turk Neurosurg. 2009; 19: 96–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tortora F Napoli M Caranci F et al. Spontaneous regression of syringomyelia in a young patient with Chiari Type I malformation. Neuroradiol J. 2012; 25: 593–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caranci F Brunese L Reginelli A et al. Neck neoplastic conditions in the emergency setting: role of the multidetector computed tomografy. Semin. Ultrasound CT MR. 2012; 33 (5): 443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caranci F Napoli M Cirillo M et al. Basilar artery hypoplasia. Neuroradiol J. 2012; 25 (6): 739–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Divitiis O Elefante A De Divitiis E. Historic background of spinal disorders. World Neurosurg. 2013; 79 (1): 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Divitis O Elefante A. Cervical spinal brucellosis: A diagnostic and surgical challenge. World Neurosurg. 2012: 78 (3–4): 257–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elefante A Peca C Del Basso De Caro ML et al. Symptomatic spinal cord metastasis from cerebral oligodendroglioma. Neurol Sci. 2012; 33 (3): 609–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinto A Caranci F Romano L et al. Learning from errors in radiology: a comprehensive review. Semin. Ultrasound CT MR. 2012; 33 (4): 379–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cirillo M Caranci F Tortora F et al. Structural neuroimaging in dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012; 29 (Suppl. 1): 16–19. [Google Scholar]