Abstract

A variety of protocols have been developed which demonstrate a capability to differentiate human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) into kidney structures. Our goal was to develop a high efficiency protocol to generate nephron progenitor cells (NPCs) and kidney organoids to facilitate applications for tissue engineering, disease modeling and chemical screening. Here, we describe a detailed protocol resulting in high efficiency production (80–90%) of NPCs within 9 days of differentiation from hPSCs. Kidney organoids were generated from NPCs within 12 days with high reproducibility using 96-well plates suitable for chemical screening. The protocol requires skills in culturing hPSCs and careful attention to morphological changes indicative of differentiation. This kidney organoid system provides a platform for studies of human kidney development, modeling of kidney diseases, nephrotoxicity, and kidney regeneration. The system provides a model for in vitro study of intracellular and kidney inter-compartmental interactions using differentiated human cells in an appropriate nephron and stromal context.

Keywords: Kidney, Organoid, iPS, Pluripotent stem cell, Directed differentiation, Nephrotoxicity, Kidney development, Cisplatin, KIM-1, Glomeruli, Tissue engineering

Introduction

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) are an important tool for regenerative medicine and disease modeling in vitro 1,2. To date, however, the protocols used for the differentiation of hPSCs into specific kidney cell types with high efficiency, without the need for less well defined inducers such as embryonic spinal cords, have eluded many researchers 3–5. Significant advances have been made within the past decade that draw upon our knowledge of kidney development to differentiate PSCs into cells of the kidney lineage 3–14. By recapitulating metanephric kidney development in vitro, we generated nephron progenitor cells (NPCs) with 80–90% purity within 9 days, without subpopulation selection during the directed differentiation protocol 15. hPSC-derived NPCs possess the developmental potential of their in vivo counterparts 15, forming renal vesicles that self-pattern into nephron structures. In both 2D and 3D culture, NPCs form kidney organoids containing epithelial nephron-like structures expressing markers of podocytes, proximal tubules, loops of Henle and distal tubules in organized, continuous structures that resemble the nephron in vivo15.

Development of the protocol

A recent study from Taguchi et al. revealed that the origin of the metanephros is distinct from the ureteric bud or pro/mesonephric lineages 5. They showed that the metanephros arises from the posterior intermediate mesoderm, whereas the ureteric bud and the pro/mesonephros is derived from anterior intermediate mesoderm. Therefore, we hypothesized that the specific induction of posterior intermediate mesoderm cells from hPSCs would greatly facilitate the induction of NPCs and avoid contamination with pronephric or mesonephric cells. Previous studies revealed that locations in the primitive streak define the subsequent differentiation into each segment of mesoderm i.e. paraxial, intermediate or lateral plate mesoderm 16. In addition, the timing of cell migration from the primitive streak defines the anterior-posterior axis in mesoderm, suggesting that the late stage of the primitive streak induces posterior mesoderm 17. We optimized the time of treatment with the GSK-3β inhibitor, CHIR99201 (CHIR), an inducer of the primitive streak, to induce late stage primitive streak. Additionally, we employed BMP4 inhibitors, as high BMP4 activity induces more posterior aspects of the primitive streak, which develops into lateral plate mesoderm 18. With this approach, we found a highly efficient protocol to induce SIX2+SALL1+WT1+PAX2+EYA1+ NPCs from both human ESCs and iPSCs with 80–90% efficiency within 9 days of differentiation. After the induction of NPCs, we transiently treated cells with CHIR (3 μM), generating multi-segmented nephron structures with characteristics of podocytes, proximal tubules, loops of Henle, and distal tubules sequenced in a self-assembled tubule in a manner that reflects normal nephron structure 15. Further analyses of other organoid compartments revealed CDH1+AQP2+ tubules and PDGFRβ+, endomucin+, or α-SMA+ interstitial cells in the kidney organoids (Supplementary Fig. 1, unpublished data generated by R.M. and N. Gupta). Collectively, our protocols generated kidney organoids consisting of multiple kidney compartments with cellular proportion similar to that of in vivo kidneys where nephrons occupy nearly 90% of renal cortex 19.

Applications of the methods

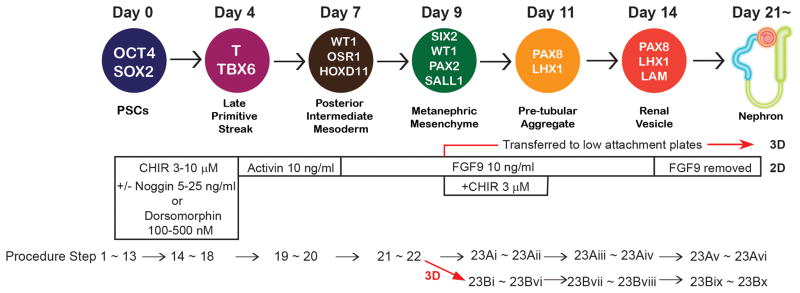

The protocols to differentiate hPSCs into NPCs and kidney organoids provide novel in vitro platforms to study human kidney development and developmental disorders, inherited kidney diseases, kidney injury, nephrotoxicity testing, and kidney regeneration. In addition, the organoids provide in vitro systems for the study of intracellular and intercellular kidney compartmental interactions using differentiated cells. Since the protocols were derived to follow the steps of kidney development as we know them in vivo, we can induce intermediate cell populations at each step of differentiation: late mid primitive streak, posterior intermediate mesoderm, NPCs, pre-tubular aggregates, renal vesicles, and nephrons (Fig. 1). Therefore, the organoids may enable the study of human kidney development and kidney congenital abnormalities by evaluating the cells at each step of differentiation. An important application will be to study inherited kidney diseases. There are more than 160 inherited kidney diseases with specific identified mutations 20. By generating iPSCs from patients with inherited kidney diseases, and producing kidney organoids from these cells, the pathogenesis of inherited kidney diseases could be explored. Moreover, it is also possible to study inherited kidney diseases by introducing targeted mutations with CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in hPSCs and taking advantage of comparisons of organoids from mutated and parental lines with otherwise uniform genetic background 14,21,22. These approaches will enable the analysis of inheritable disease pathophysiology and allow for drug screening in vitro to find new therapeutic approaches. Another application of kidney organoids will be to test nephrotoxicity of drugs in predictive toxicology based on genotypic characteristics of an individual. Since the kidney organoids contain multiple cell types, reflecting sequential segments of the nephron from podocytes to distal tubules, it will be possible to assign drug toxicity to specific nephron segments. The maintenance of a differentiated phenotype in vitro will also allow for cellular biochemical analyses and the study of inter-compartmental interactions in ways that may mimic the status in vivo more closely than typical cell culture studies where the cells are generally dedifferentiated. The presence of CDH1+AQP2+ tubules and PDGFRβ+, endomucin+, or α-SMA+ interstitial cells, will permit studies of nephron-interstitial cell interactions. Ultimately, the protocol has the potential to serve as a foundation to provide organoids for kidney regenerative therapies.

Figure 1. The differentiation protocols into kidney organoids from hPSCs.

The diagram shows markers for each step of differentiation in a sequential pattern identifying days of differentiation. OCT4: POU class 5 homeobox 1. SOX2: SRY-box 2. T: brachyury. WT1: Wilms tumor 1. OSR1: odd-skipped related transcription factor 1. HOXD11: homeobox D11. SIX2: SIX2 homeobox 2. PAX2: paired box 2. SALL1: spalt like transcription factor 1. PAX8: paired box 8. LHX1: LIM homeobox 1. LAM: laminin. The concentration of each growth factor and small molecule necessary for each stage of differentiation is shown as well as corresponding procedural step numbers. This figure is modified from the one published previously 15.

Researchers can chose 2D or 3D kidney organoid generation based on their study goals. Generation of kidney organoids with 2D culture is possible even with low efficient induction of NPCs; therefore, it would be easier to generate kidney organoids with less efforts on adjusting differentiation protocols. Generation of kidney organoids with 3D culture requires high induction efficiency of NPCs; however, it enables to make frozen sections which allow to investigate immunohistochemistry with multiple antibodies from the same sample. For detailed evaluation on disease phenotypes, 3D culture is recommended, since structures of nephrons are more similar to in vivo nephrons with clear lumen formation of tubules than with 2D culture.

Comparison with other methods

In comparing our protocol to previous published protocols to induce kidney lineage cells, there are many differences in efficiency, specificity, and simplicity. Our protocols yield NPCs, with much higher induction efficiency, from both hESCs and hiPSCs when compared to previous studies, including our own 3,4,13,14,23. High induction efficiency at each step of differentiation, simultaneously, indicates high specificity of kidney induction. Taguchi et al. reported relatively high efficiency (~60%) of SIX2+ cell induction with embryoid body formation, yet co-culture with mouse embryonic spinal cords is required to generate kidney epithelial cells while our protocols use monolayer culture and chemically defined components which don’t require preparation of pregnant mice and mouse embryonic spinal cords for kidney organoid generation 5. We were able to generate NPCs and organoids using fully defined conditions without the addition of any non-purified factors, which is desirable for regenerative utility in humans. In addition, our protocols use 96-well, round bottom, ultra-low attachment plates to generate 3D kidney organoids, which enables mass production of kidney organoids, while the other protocols to generate organoids require pelleting cells in eppendorf tubes or co-culture with mouse embryonic spinal cords 5,13. As previous studies have shown, the efficiency of the same differentiation protocol differs in separate hPSC lines 24 therefore adjustments must be made to achieve similar results in varying lines. We define how to adjust the protocol for different lines of hPSCs, which further facilitates the applicability of our differentiation protocols. The dose of growth factors can greatly influence the costs of the directed differentiation protocols. We were able to use lower doses of FGF9 than those used in the excellent protocol of Takasato et al 13. This has substantial financial advantages at the present time.

Other protocols result in generation of CD31+ endothelia-like cells 13,14 and CDH1+GATA3+ collecting duct-like cells 13 which can be perceived as a shortcoming of our protocol. We now have unpublished data that documents the presence of CDH1+AQP2+ tubules and PDGFRβ+, endomucin+, or α-SMA+ interstitial cells in the kidney organoids (Supplementary Fig. 1, unpublished data generated by R.M. and N. Gupta). The cells expressing these markers require more characterization and one of our goals is to understand how these populations might be enhanced in our protocol. Non-nephron cells are useful to establish a multi-compartment environment in the kidney organoids potentially leading to vascularization of glomerular and tubulo-interstitial structures. The ability to generate NPCs with high efficiency and ultimately multi-segmented nephrons serves as a very good starting point for subsequent bioengineering of functional kidney tissues.

Limitations

The differentiation efficiency is affected by the variability intrinsic to hPSC lines. We have clarified how to adjust the protocol for different cell lines grown initially in different culture conditions, reflecting our experience with 2 different culture media and multiple hPSC lines. We recommend use of H9 and ReproFF2, as the simplest methods to achieve high differentiation efficiency. We believe that theour adjustment method will enable researchers in different environments to generate NPCs and kidney organoids with different culture systems and different cell lines.

Another limitation of our protocols is that the cells in the interstitial space of kidney organoids were not well characterized in our original study because of lack of validated antibodies in human kidney samples and definitive morphological characteristics. Those cells were presumably derived from SIX2-negative population which accounted for 10~20% of cells at the NPC stage, and could be collecting duct cells, pericytes, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts or others according to published studies 12,28,29. Our recent unpublished results showed CDH1+AQP2+ tubules (characteristic of connecting tubules and collecting ducts 25) and PDGFRβ+ (characteristic of pericytes 26), endomucin+ (characteristic of endothelial cells 27), or α-SMA+ (characteristic of myofibroblasts 26) interstitial cells in the organoids (Supplementary Fig. 1, unpublished data generated by R.M. and N. Gupta); however, further definitive analyses of these cells are ongoing. We therefore hope that further studies from us and other investigators will elucidate the characteristics and state of cell types in the interstitial space. We believe that the organoid system derived from our protocols is appropriate to study the interactions between nephron epithelial cells and interstitial cells in a human in vitro model system which recapitulates the complexities of these interactions in the intact organ. In this way we hope to unlock new insight into processes such as kidney fibrosis, a fundamental process resulting in chronic kidney disease.

Experimental design

Feeder-free hPSC culture in ReproFF2 medium (step 1–6)

Our protocols use feeder-free hPSC culture in ReproFF2 medium with lactose dehydrogenase elevating virus (LDEV)-Free hESC-qualified Geltrex-coated plates 4,15. We maintain hPSCs in 6-well plates coated with 1% LDEV-Free hESC-qualified Geltrex with ReproFF2 medium, supplemented with fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), 10 ng/ml (step 1–6). If hPSCs were initially cultured on mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeders, we recommend passaging the cells at least 5 times under feeder-free conditions with ReproFF2. If hPSCs cannot be maintained in ReproFF2, we recommend using StemFit Basic supplemented with FGF2 (10 ng/ml) using 6-well plates coated with 1% LDEV-Free hESC-qualified Geltrex 28 (Box 1) (unpublished data generated by R.M.). hPSCs are passaged every 7 days. The difference between ReproFF2 and StemFit Basic is the method to passage cells. In ReproFF2, cells are passaged by clump-passage, an original passaging method of hPSCs which is used in many types of hPSC maintenance media. On the other hand, StemFit Basic uses single cell passaging with a ROCK-inhibitor.

Box 1. An alternative maintenance protocol for hPSCs with StemFit Basic medium in feeder-free culture TIMING 7 d.

CRITICAL

All maintenance culture experiments described here use StemFit Basic and 6-well plates coated with 1% LDEV-Free hESC-qualified Geltrex.

-

1|

When cells reach 80% confluence, aspirate StemFit Basic and add 2 ml of PBS to wash out the remaining medium. Aspirate PBS and add 500 μl of Accutase. Place cells in an incubator at 37 °C for 10 min. Fully dissociate cells with 1ml pipette and transfer cells to 15 ml tube filled with 500 μl of StemFit Basic.

-

2|

Take 20 μl from 15 ml tubes to a Cellometer Counting Chamber for cell counting with a Cellometer. Centrifuge tubes at 300 × g at room temperature for 4 min. While centrifuging tubes, count the cell number with a Cellometer.

-

3|

Aspirate the media and resuspend cells at 10,000 cells/μl in StemFit Basic.

-

4|

Aspirate Geltrex solution from the new well and add 1.5 ml StemFit Basic. Directly add 1.5 μl of Y27632 (final concentration: 10 μM) to the well and briefly shake the plate.

-

5|

Directly add 1~2 μl of resuspended cells to the new well (10,000~20,000 cells/well).

CRITICAL STEP It is important to adjust the plating cell number in different lines of hPSCs. We usually plate 15,000 cells of H9 per well.

-

6|

Culture the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for one day. Aspirate the medium and feed cells with 1.5 ml of StemFit Basic to remove Y27632.

-

7|

Feed cells with 1.5 ml of StemFit Basic after three, and five days.

-

8|

Passage cells every 7 days.

Preparation of hPSCs for differentiation (step 7–13)

The cells are plated for differentiation when the cells are passaged (step 7–13). We usually prepare 2 wells of 6-well plates, and use one well for differentiation and one well for continued passaging. Plating density significantly affects the differentiation efficiency, and each line of hPSCs requires adjustment. For H9 cells, approximately 20,000 cells/cm2 was best in our experience. For HDF-α iPS cells, approximately 14,000 cells/cm2 was optimal. Pluripotency of hPSCs needs to be well maintained in the undifferentiated cells, and hence differentiated colonies need to be removed by aspiration. To prepare cells for differentiation, the cells are dissociated with Accutase for 15 min, resuspended in ReproFF2 supplemented with FGF2 10 ng/ml and Y27632 10 μM 29, and plated onto 24-well plates pre-coated with 1% LDEV-Free hESC-qualified Geltrex. The cells are cultured for 72 hours until they reach approximately 50% confluency.

Nephron progenitor cell induction (step 14–22)

Figure 2 shows the cellular morphology upon initiation of differentiation. The confluency at initiation significantly affects the differentiation efficiency; therefore, we strongly recommend the preparation of different plating densities until you find the best condition. First, the cells are briefly washed with PBS once in order to remove the remnant of ReproFF2 (or StemFit). Then, differentiation is initiated with CHIR99021 (CHIR 30) 3~10 μM +/− a BMP4 inhibitor (noggin 5~25 ng/ml or dorsomorphin 100~500 nM). Each line of hPSCs requires a dose adjustment of CHIR. The highest dose which does not lead to cell detachment or death during 4 days of CHIR treatment is recommended. The addition of a BMP4 inhibitor depends on the cell line and the maintenance conditions that you use. When we use H9 cells maintained in ReproFF2, we do not require the addition of a BMP4 inhibitor to CHIR 8 μM. For HDF, 10 μM of CHIR with 5 ng/ml noggin was best. Addition of a BMP4 inhibitor does not change the subsequent differentiation protocol. If you use other cell lines or other culture media, adjust the protocol as follows: First, adjust the plating cell number to obtain 50% confluency when differentiation is initiated. Second, find the highest concentration of CHIR (3~10 μM) which does not lead to cell detachment and death during 4 days of CHIR treatment. Third, test addition of a BMP4 inhibitor (noggin 5~25 ng/ml or dorsomorphin 100~500 nM), if the adjustment of the plating cell number and CHIR was not sufficient to induce SIX2+ cells. This first step of differentiation generally takes 4 days. The medium should be changed on day 2 of the differentiation. On day 4 of differentiation, the cells form loosely dense clusters (Fig. 2). This identifies the best time to proceed to the next step of differentiation, which involves treating the cells with activin A at 10 ng/ml.

Figure 2. Morphological changes of hPSCs at each step of differentiation.

Representative bright field imaging at each step of differentiation. Day 0, undifferentiated hPSCs (H9) when differentiation is initiated. Day 4, late primitive streak stage. Day 9, nephron progenitor stage. Day 14, renal vesicle stage. Day 21, nephron stage. The optimal morphology of cells to proceed to activin A treatment on day 4 is the visual presence of loosely dense clusters. Representative bright field imaging of “too loose” or “too dense” clusters on day 4 is also shown. Scale bar: 100 μm. The scale bar is representative of all panels.

After 3 days of activin A treatment, the markers for posterior intermediate mesoderm, namely WT1 and HOXD11, become positive. Then, the cells are treated with FGF9, 10 ng/ml, for 2 days to induce NPCs. On day 9 of differentiation, a critical marker for NPCs, SIX2, becomes positive. SIX2 staining is very bright when the differentiation is induced appropriately (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3. Immunostaining for NPCs and nephrons.

(a) Immunocytochemistry for SIX2 at day 9 of differentiation revealing NPCs. Scale bar: 50 μm. (b) Immunocytochemistry to identify nephron segments in 2D culture on day 21 of the differentiation. Scale bar: 50 μm. (c) Immunohistochemistry to identify nephron segments in 3D culture with frozen sections on day 21 of differentiation. Scale bar: 50 μm. (d) Whole mount staining for nephrons in 3D culture on day 28 (left: high magnification, scale bar: 50 μm) and 21 (right: low magnification, scale bar: 100 μm). The inset on the right shows DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining. PODXL: podocalyxin (a podocyte marker). LTL: lotus tetragonolobus lectin (a proximal tubule marker). CDH1: cadherin1 (also known as E-cadherin) (a loop of Henle and distal tubule marker). (e) Bright field imaging of an organoid in 3D culture on day 21. Arrows indicate a glomerular structure. Scale bar: 100 μm. (c) and the left panel of (d) were originally published in ref 15.

Kidney organoid induction (step 23)

From this nephron progenitor cell stage, we can apply the same differentiation treatment in either 2D (step 23A) or 3D (step 23B) culture. When we switch to 3D culture, we use 96-well, round bottom, ultra-low attachment plates, and plate 100,000 cells/well. Usually, we obtain 2~3 million cells from one well of 24-well plates, which is sufficient to generate many organoids. In both 2D and 3D culture, we treat NPCs with CHIR 3 μM and FGF9 10 ng/ml for 2 days in order to induce pre-tubular aggregates (PAX8+LHX1+). Then, we switch back to FGF9, 10 ng/ml alone, and culture the cells for 3 days to differentiate them into renal vesicles (PAX8+LHX1+LAM+). After that, we use only the basic differentiation medium without any growth factors, and the cells form segmented-nephron structures within one week. The kidney organoids generated by our protocols are stable in the basic differentiation medium for up to 3 months with feeding every 2~3 days.

Endpoint analysis (step 24)

Typically, nephron structures are visible after 3~5 days of culture after the “renal vesicle stage” in 2D culture (Fig. 2). In 2D culture, segmented-nephron structures can be analyzed by standard immunocytochemistry for markers of podocytes (PODXL), proximal tubules (lotus tetraglonolobus lectin (LTL)), loops of Henle (cadherin 1 (CDH1), uromodulin (UMOD)), and distal tubules (CDH1) (step 24A) (Fig. 3b). In 3D culture, frozen sections can be made by standard protocols 31, and nephron structures can be analyzed by immunohistochemistry (step 24B) (Fig. 3c). Alternatively, whole mount staining can also be performed, which enables the observation of 3D nephron structures with confocal microscopy (step 24C) (Fig. 3d). Glomerular and tubular structures can occasionally be recognized with bright field imaging near the surface of the organoids (Fig. 3e).

Nephrotoxicity assay with cisplatin (Box 2)

Box 2. Nephrotoxicity assay with cisplatin TIMING 2 d.

Prepare kidney organoids in either 2D or 3D culture after at least 21 days of the differentiation.

Prepare the basic differentiation medium supplemented with cisplatin 5 μM (1:1000 dilution) or sterile water as a negative control. Required volume for 1 well of 3D culture or 2D culture is 200 μl or 500 μl respectively.

CRITICAL STEP Make sure there is no precipitation of cisplatin in the aliquot. If you see precipitation when the aliquot is taken out from the freezer, warm up the aliquot in a water bath at 37 °C until cisplatin is completely dissolved.

Gently aspirate the medium and add 200 μl (3D) or 500 μl (2D) of the basic differentiation medium supplemented with cisplatin 5 μM or sterile water.

CRITICAL STEP Aspiration of kidney organoids would damage tubules, which might result in induction of KIM-1 expression. Be careful not to aspirate kidney organoids.

Culture the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for one day. Harvest samples for your analyses (Endpoint analysis A–C).

There are a variety of possible applications using NPCs and kidney organoids. As an example of one of these applications, we show a nephrotoxicity assay with cisplatin, a known nephrotoxicant (Fig. 4). Once nephron structures formed in kidney organoids (day 21~), you can treat the organoids with agents to interrogate nephrotoxicity. We demonstrate the response to cisplatin, a known nephrotoxicant. We used KIM-1 staining to detect proximal tubular injury 32.

Figure 4. Nephrotoxicity assay.

Immunohistochemical staining for CDH1 (cadherin1), KIM1 (kidney injury molecule1), and LTL (lotus tetragonolobus lectin) in kidney organoids after 24 hours treatment with cisplatin 5 μM. LTL+ tubules expressed KIM1 after the treatment, which is a marker for proximal tubular injury. Kidney organoids generated in 3D culture were treated with cisplatin 5 μM for 24 hours from day 23 to 24 of the differentiation. Organoids were fixed and analyzed on day 24. Scale bars: 50 μm. The scale bars are representative of the corresponding right panels.

Materials

REAGENTS

Accutase (STEMCELL Technologies, 07920)

Activin (R&D systems, 338-AC-050)

Advanced RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, 12633-020)

Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) (Roche, 10735094001)

CHIR99021 (TOCRIS, 4423) CRITICAL The same product is required for successful differentiation experiments. Alternative replacements need to be tested to determine the optimal concentration for the differentiation.

Cisplatin (Sigma, P4394)

DAPI (Sigma, D8417)

Dissociation Solution for human ES and iPS cells (CTK solution) (ReproCELL, RCHETP002)

DMEM/F12 (Life Technologies, 11320-033)

DMSO (TOCRIS, 5 × 5 ml, 3176)

Dorsomorphin (TOCRIS, 3093)

Geltrex (LDEV-Free hESC-qualified) (Life Technologies, A1413302)

H9 hESC line (WiCell), passage 45–65 !CAUTION The cell lines in your research should be regularly checked to ensure they are authentic and are not infected with mycoplasma. Appropriate national laws and institutional regulatory board guidelines must be followed to use hPSCs. We obtained the permission to use hPSCs from our Institutional Review Board (IRB) and institutional Embryonic Stem Cell Research Oversight (ESCRO) committee. H9 was authenticated by short tandem repeat (STR) DNA profiling. Mycoplasma contamination was not detected.

-

HDF-α iPS cells 33, passage 22–42

!CAUTION The cell lines in your research should be regularly checked to ensure they are authentic and are not infected with mycoplasma. Appropriate national laws and institutional regulatory board guidelines must be followed to use hPSCs. We obtained the permission to use hPSCs from our Institutional Review Board (IRB) and institutional Embryonic Stem Cell Research Oversight (ESCRO) committee.

human FGF2 (Peprotech, 100-18B)

human FGF9 (R&D systems, 273-F9-025/CF)

human Noggin (Peprotech, 120-10C)

L-GlutaMAX (Life Technologies, 35050-061)

O.C.T compound (Fisher Scientific, 23-730-571)

Paraformaldehyde 16% (PFA, Electron Microscopy Sciences, RT15710) !CAUTION Handle PFA inside chemical hoods with gloves to avoid skin contact.

PBS (Life Technologies, 10010-049)

ReproFF2 (ReproCELL, RCHEMD006)

StemFit Basic (Ajinomoto, ASB01)

Streptavidin/Biotin Blocking Kit (Vector Labs, SP-2002)

Vectashield (Vector Labs, H-1200)

Y-27632 dihydrochloride (TOCRIS, 1254)

ANTIBODIES

α-SMA (Sigma, F3777), used at 1:500 dilution

Aquaporin2 (Millipore, AB3274), 1:100 dilution

E-cadherin (CDH1) (Abcam, ab11512), 1:500 dilution

Endomucin (Abcam, ab45771), 1:500 dilution

HOXD11 (Sigma, SAB1403944) 1:100

KIM1 (R&D, AF1750), 1:500

Laminin (Sigma, L9393) 1:500

LHX1 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, 4F2-c) 1:50

LTL (lotus tetragonolobus lectin) (Vector lab,B-1325) 1:200

PAX8 (Proteintech, 10336-1-AP) 1:500

PDGFR-β (Novus, AF385), 1:100

Podocalyxin (PODXL) (R&D systems, AF1658) 1:500

SIX2 (Proteintech, 11562-1-AP) 1:500

Uromodulin (Biomedical Technologies, BT-590) 1:150

WT-1 (Santa cruz, sc192) 1:50

EQUIPMENT

Cellometer (Nexcelom)

Cellometer Counting Chambers (Nexcelom)

Confocal microscopy (Nikon C1, Tokyo, Japan)

Inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti)

Inverted microscope (Axiovert 40 CFL)

6-well tissue culture plates (Falcon, 353046)

24-well tissue culture plates (TPP, 92024)

96-well, round bottom, ultra-low attachment plates (Corning, 7007)

Biosafety cabinet (The Baker Company, SterilGARD Hood)

Centrifuge (Eppendorf, 5810R; Thermo Scientific, Jouan B4i)

CO2 incubator (Thermo Scientific, Forma series II water Jacket)

Cryostat (Leica, CM1510S)

REAGENT SETUP

Human pluripotent stem cells

Before initiating differentiation, adapt hPSCs to feeder-free cultures in ReproFF2 or StemFit in 6-well plates coated with 1% LDEV-Free hESC-qualified Geltrex (step 1–6).

ReproFF2

Make 45ml aliquots and store in −20 °C for up to 6 months. Thaw the aliquot in a refrigerator overnight, and add FGF2 10 ng/ml. Keep the medium in a refrigerator at 4°C and use it within a week.

StemFit Basic

Make 45ml aliquots after mixing A and B solution, and store in −20 °C for up to 6 months. Thaw the aliquot in a refrigerator overnight, and add FGF2 10 ng/ml. Keep the medium in a refrigerator at 4°C and use it within a week.

Basic differentiation medium

Add 5 ml L-GlutaMAX to 500 ml advanced RPMI 1640. Keep the medium in a refrigerator at 4°C and use it within a month.

Geltrex-coated plates

Add LDEV-Free hESC-qualified Geltrex to cold DMEM/F12 at 1:100 ratio. Add 1 ml total volume to 1 well of 6-well plate or 300 μl to 1 well of 24-well plates. Incubate the plates in a 37 °C incubator for at least one hour. Store the coated plates in a refrigerator at 4°C and use them within a week. Before seeding cells onto the plates, place the plates on a clean bench for at least 30 min at room temperature (20–25 °C).

!CAUTION Keep Geltrex on ice to avoid it solidifying.

PBS with Triton X-100 0.3% vol/vol (PBST, 500ml)

Add 1.5 ml Triton X-100 to 500 ml PBS and shake well. Keep at room temperature and use it within 12 months.

Antibody dilution buffer (PBST-BSA 1% wt/vol, 40ml)

Add 400 mg bovine serum albumin to 40 ml PBST and shake well. Keep at 4°C and use it within one month.

Blocking buffer (PBST-donkey serum 5% vol/vol, 20ml)

Add 1 ml donkey serum to PBST and shake well. Keep at 4°C use it within two weeks.

PFA, 4% wt/vol (40ml)

Add 10 ml 16% PFA to 30 ml PBS. Keep at 4°C and use it within two weeks.

FGF2 (10 μg/ml)

Reconstitute 100 μg FGF2 in 10 ml PBS with 0.1% (w/v) BSA. Make small aliquots and keep at −20 °C for up to 6 months. Once it has been thawed, store the aliquot in a refrigerator at 4°C and use it within one week.

CHIR (10 mM)

Reconstitute 10 mg CHIR in 2.149 ml DMSO. Make small aliquots (60 μl) and keep at −20 °C for up to 6 months. Once it has been thawed, store the aliquot in a refrigerator at 4°C and use it within one week.

Noggin (100 μg/ml)

Reconstitute 20 μg noggin in 200 μl PBS with 0.1% (w/v) BSA. Make small aliquots (10 μl) and keep at −20 °C for up to 6 months. Once it has been thawed, store the aliquot in a refrigerator at 4°C and use it within two weeks.

Dorsomorphin (10 mM)

Reconstitute 10 mg dorsomorphin in 2020 μl DMSO. Make small aliquots (50 μl) and keep at −20 °C for up to 12 months. Once it has been thawed, store the aliquot in a refrigerator at 4°C and use it within one week.

Activin A (50 μg/ml)

Reconstitute 50 μg activin A in 1 ml PBS. Make small aliquots (20 μl) and keep at −20 °C for up to 12 months. Once an aliquot has been thawed, store it in a refrigerator at 4°C and use it within two weeks.

FGF9 (100 μg/ml)

Reconstitute 25 μg FGF9 in 250 μl PBS with 0.1% BSA. Make small aliquots (10 μl) and keep at −20 °C for up to 6 months. Once the aliquot has been thawed, store it in a refrigerator at 4°C and use it within two weeks.

Y27632 (10 mM)

Reconstitute 10 mg Y27632 in 3.0792 ml PBS. Make small aliquots (80 μl) and keep at −20 °C for up to 6 months. Once the aliquot has been thawed, store it in a refrigerator at 4°C and use it within one week.

Cisplatin (5 mM)

Reconstitute 15 mg cisplatin in 10 ml sterile water. Make small aliquots and keep at −20 °C for up to 6 months. Once the aliquot has been thawed, store it in a refrigerator at 4°C and use it within two weeks.

PROCEDURE

Maintenance of hPSCs in feeder-free culture with ReproFF2 TIMING 7 d

CRITICAL All maintenance culture experiments described here use ReproFF2 and 6-well plates coated with 1% LDEV-Free hESC-qualified Geltrex.

-

1|

Before passaging hPSCs, check the cell conditions and extent of spontaneous differentiation. Healthy undifferentiated hPSCs display round colony morphology with a clear boundary. Proceed to the next step when the colonies are ~80% confluent. Unlike when grown on feeder culture, it is usual to observe some merged colonies.

CRITICAL STEP Differentiated cells are usually located at the center of the colony when the size of each colony becomes too large. Some differentiated cells exhibit fibroblast-like morphology at the periphery of the colonies. In this case it is difficult to remove differentiated cells therefore, it is better to retry transition from “on feeder” to “feeder-free” from the beginning.

TROUBLESHOOTING

-

2|

Aspirate differentiated colonies by visual recognition. Small differentiated colonies will spontaneously disappear upon passaging; therefore, it is sufficient to remove only large differentiated colonies. Aspirate ReproFF2 and add 200 μl of Dissociation Solution for human ES/iPS cells (CTK solution) from the center of the well in order to distribute the solution to the entire surface area. Incubate the cells in an incubator at 37 °C for 2 min until the edges of the colonies start to roll up. Aspirate CTK solution and add 2 ml of PBS to wash away the remnant CTK solution.

CRITICAL STEP It is important to be careful with treatment with CTK solution which can be detrimental if cells are exposed too long. If you wait too long, colonies will be lost when subsequently washed with PBS. Hence, it is important to perform a visual check, with or without a microscope, for cell detachment after 2 min of exposure to CTK. When you notice that the periphery of colonies start to roll up, it is time to proceed to the next step. We recommend checking cells every 15 sec after 2 min of incubation with CTK solution.

-

3|

Aspirate PBS and add 1 ml of ReproFF2. Detach colonies using a cell scraper. Break up colonies with a 1 ml pipette until you cannot visualize large aggregates. Pipetting is usually performed 3~10 times (depends on confluency and cell lines).

CRITICAL STEP The optimal size of colonies depends on the cell lines, the confluency, and the passage number in feeder-free culture. The optimal diameter of colonies is 100~200 μm when the cells are optimized to feeder-free culture.

-

4|

Prepare a new plate at room temperature for 30 min. Aspirate Geltrex solution from the new well, and add 1~1.7 ml of ReproFF2 depending on the passage ratio (total will be 2 ml).

-

5|

Transfer 330 μl~1 ml (1:1~1:3 ratio) of the colony fragments into 1 well of the new plate and shake the plates gently in order to distribute the colonies equally in the well.

-

6|

Maintain the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Replace the medium after 3 days and 5 days. Passage the cells every 7 days.

Preparation of hPSCs for differentiation TIMING 3 d

CRITICAL All differentiation experiments use 24-well plates coated with 1% LDEV-Free hESC-qualified Geltrex.

-

7|

Check the confluency and spontaneous differentiation of the cells on the day of passaging. Usually, there are very few differentiated cells; therefore, it is not necessary to remove differentiated cells when you prepare the cells for differentiation. If differentiated cells are observed, aspirate the differentiated cells and grow smaller colonies in subsequent passages.

CRITICAL STEP If the confluency is not high enough, passage the cells at 1:1 ratio until the confluency is nearly 80%. Less confluency will result in poor viability of cells and inefficient differentiation once initiated. If the differentiated cells are observed in more than 5 % colonies, further passaging is necessary before undertaking the differentiation protocol.

-

8|

Aspirate ReproFF2 and add 2 ml of PBS. Gently swirl the plate to wash out the remnants of ReproFF2. Aspirate PBS and add 500 μl of Accutase. Incubate the cells in an incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 10 min. Tap the plate to facilitate detachment of cells. Incubate for another 5 min.

-

9|

After incubation for 15 min in total, detach and dissociate the cells with a 1 ml pipette gently until you cannot recognize cell aggregates. Prepare 15 ml tubes by adding 500 μl ReproFF2.

-

10|

Collect the dissociated cells into 15 ml tubes filled with 500 μl ReproFF2. Take 20 μl from 15 ml tubes to a Cellometer Counting Chamber for cell counting.

-

11|

Centrifuge tubes at 300 g at room temperature for 4 min. While centrifuging tubes, count the cell number with a Cellometer. Aspirate the medium and resuspend cells at 10,000 cells/μl in ReproFF2.

CRITICAL STEP When you collect cells from 1 well of 6-well plates, usually you have 2~5 million cells. If you have fewer than 1 million cells, the cell confluency in the hPSC culture was too low, which will result in poor viability of cells when differentiation is initiated.

-

12|

Aspirate the supernatant and resuspend the cells at 10,000 cells/μl in ReproFF2. Prepare a sufficient amount of ReproFF2 with 10 μM of ROCK inhibitor Y27632 (1:1000 dilution) for the differentiation experiments. Transfer the cell suspension to ReproFF2 with Y27632 in order to have 44,000~86,000 cells/ml (12,000~24,000 cells/cm2). Plate cells in 500 μl/well of 24-well plates.

CRITICAL STEP The plating density is critically important to achieve high efficiency of differentiation. It is vital to test different plating densities when you use different cell lines. For H9 cells, approximately 20,000 cells/cm2 was best in our experience. For HDF-α iPS cells, approximately 14,000 cells/cm2 was optimal. In addition, the size of the well is also very important. If you want to change the size, it is necessary to test different plating densities.

TROUBLESHOOTING

-

13|

Culture the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 72 hours. There is no need to change the medium.

CRITICAL STEP If you want to start the differentiation earlier, you need to plate more cells at step 12 to have nearly 50% confluent cells when you start the differentiation.

Differentiation of hPSCs into posterior intermediate mesoderm cells TIMING 6~7 d

-

14|

Check the cell confluency. About 50% is the best to start the differentiation. Aspirate ReproFF2 and add 500 μl PBS to wash out the remnant of ReproFF2.

CRITICAL STEP The confluency when beginning differentiation affects cell viability and differentiation efficiency. If the confluency is less than 50%, you can adjust the timing to start the differentiation later.

-

15|

Aspirate PBS and add 500 μl of the differentiation basal medium supplemented with CHIR 3~10 μM +/− a BMP4 inhibitor (noggin 5–25 ng/ml, or dorsomorphin 100–500 nM).

CRITICAL STEP The concentration of CHIR and addition of a BMP4 inhibitor depends on the cell line, the passaging number, and maintenance culture conditions. For H9, 8 μM of CHIR was best with ReproFF2 culture. For HDF, 10 μM of CHIR with 5 ng/ml noggin was best. If you use other cell lines or other culture media, adjust the protocol as follows: First, adjust the plating cell number to obtain 50% confluency when differentiation is initiated. Second, find the highest concentration of CHIR (3~10 μM) which does not lead to cell detachment and death during 4 days of CHIR treatment. Third, test addition of a BMP4 inhibitor (noggin 5~25 ng/ml or dorsomorphin 100~500 nM), if the adjustment of the plating cell number and CHIR was not sufficient to induce SIX2+ cells.

TROUBLESHOOTING

-

16|

Culture the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 2 days.

-

17|

Aspirate the medium and feed cells with 500 μl of fresh differentiation medium supplemented with the same concentration of CHIR (with or without a BMP4 inhibitor).

-

18|

Culture the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 2 days.

-

19|

Check the morphology of cells. The presence of loosely formed dense clusters of cells indicates the best time to switch to the next differentiation treatment (Fig. 2). Usually, 96 h of differentiation is the best timing; however, you can adjust the timing depending on the morphology of cells. Aspirate the medium and add 750 μl of the differentiation medium with activin A 10 ng/ml.

CRITICAL STEP This stage is most important to achieve high efficiency of differentiation to NPCs. Check the morphology very carefully. If the cells still form a homogenous flat monolayer (too loose, Fig. 2), feed cells with the differentiation medium with the same concentration of CHIR (with or without a BMP4 inhibitor) and wait for one-half to one full day. If the cells form dome-like round clusters (too dense, Fig. 2), similar to undifferentiated mouse embryonic stem cells, it is often too late to proceed to the next step. Try again from the beginning of differentiation by lowering the concentration of CHIR.

-

20|

Culture the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 2~3 days. There is no need to feed cells. If the SIX2+ cell induction was not good enough, test 2 days treatment of activin A instead of 3 days.

Differentiation of hPSCs into NPCs TIMING 1~2 d

-

21|

Aspirate the medium and add 500 μl of the basic differentiation medium supplemented with FGF9, 10 ng/ml.

-

22|

Culture the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 1~2 days. You usually don’t need to feed cells, but feed cells with the basic differentiation medium supplemented with FGF9, 10 ng/ml, if the medium becomes yellow in color.

-

23|

23 Follow Option A to differentiate cells into 2D kidney organoids or Option B to differentiate hPSCs into 3D kidney organoids.

TROUBLESHOOTING

A. Differentiation of NPCs into kidney organoids (2 dimensional) TIMING 12~ d

-

Aspirate the medium and add 500 μl-1 ml of the differentiation medium with FGF9 10 ng/ml and CHIR 3 μM.

CRITICAL STEP Check the morphology of cells. If many cells form round polarized structures with lumens resembling renal vesicles (Fig. 2), you should adjust the treatment time of this step by shortening from 2 days to 1 day. If the medium color quickly changes to yellow, you should increase the volume of the medium up to 1 ml in the next experiments.

-

Culture the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 2 days.

CRITICAL STEP If the medium color becomes yellow after 1 d of culture, feed the cells with the differentiation medium using the same concentration of CHIR and FGF9 with the same volume as in step 23Ai.

Aspirate the medium and add 750 μl~1ml of the differentiation medium with FGF9, 10 ng/ml.

-

Culture the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 2~3 d. Proceed to the next step if round polarized structures with lumens, resembling renal vesicles, are observed. If renal vesicle structures are not observed within 3 days, confirm whether LHX1 is expressed by immunostaining. If LHX1 is positive in most of cells, proceed to the next step.

CRITICAL STEP If the medium color becomes yellow after 1 or 2 d of culture, feed the cells with the differentiation medium, using the same concentration of FGF9 with the same volume as in step 23AiiiTROUBLESHOOTING

Aspirate the medium and add 500 μl of the basic differentiation medium without growth factors.

Feed cells every 2~3 days with 500~750 μl of the basic differentiation medium. The kidney organoids are stable for at least up to 3 months of differentiation. Nephron structures can be recognized with a microscope (Fig. 2, Fig. 3e).

B. Differentiation of hPSCs into 3 dimensional kidney organoids TIMING 12~ d

Aspirate the medium and add 500 μl PBS. Wash out the remnant of the differentiation medium.

Aspirate PBS and add 300 μl Accutase per well of the 24-well plate. Incubate the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 10~15 min. Prepare 15 ml tubes containing 300 μl of the basic differentiation medium supplemented with CHIR 3 μM and FGF9 10 ng/ml.

Dissociate the cells with a 1 ml pipette, and transfer the cells to the 15 ml tubes. Take 20 μl from the 15 ml tubes for cell counting with a Cellometer.

Centrifuge tubes at 300 g at room temperature for 4 min. Count the cell number using a Cellometer.

Aspirate the medium and resuspend the cells in the basic differentiation medium supplemented with CHIR 3 μM and FGF9 10 ng/ml at 500,000 cells/ml. Plate 100,000 cells/well in 200 μl of the differentiation medium onto 96-well, round bottom, ultra-low-attachment plates.

Centrifuge the plates at 300 g for 15 s, and culture the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 2 days.

Gently aspirate the medium with a 200 μl pipette and add 200 μl of the basic differentiation medium supplemented with FGF9 10 ng/ml.

-

Culture the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 2~3 days until renal vesicle-like round structures become visible by a microscope.

TROUBLESHOOTING

Aspirate the medium with a 200 μl pipette, and add the basic differentiation medium without any additional growth factors.

Culture the cells at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for at least for 1 week. Aspirate 85 μl of the medium and add 100 μl of the basic differentiation medium every 2~4 days.

Endpoint analysis

24 To perform endpoint analysis for 2D kidney organoids follow option A; for endpoint analysis of 3D kidney organoids by frozen sectioning follow option B and for endpoint analysis of 3D kidney organoids by whole mount staining follow option C

A. Endpoint analysis of 2D kidney organoids TIMING 2 d

Aspirate the medium and add 200 μl of 4% PFA. Incubate the plate at room temperature for 15~30 min.

Aspirate the 4% PFA and add 500 μl PBS. Wash the well gently and aspirate PBS.

Repeat step ii 2 more times.

Aspirate PBS and add 150~200 μl of blocking buffer. Incubate the plate at room temperature for 1 h.

-

Aspirate the blocking buffer and add 150~200 μl of the antibody dilution buffer, containing the desired primary antibodies (Table 2). Incubate the plate overnight at 4 °C.

CRITICAL STEP If the surface of the wells is not covered fully by the antibody dilution buffer, increase the antibody solution amount from 150 to 200 μl. If you stain with biotinylated-LTL, it is necessary to use a streptavidin/biotin blocking kit.

Place the plate at room temperature, and wait for 15 min. Aspirate the antibody solution and add 500 μl PBS. Wash out the remnant of antibody.

Repeat washing with 500 μl PBS 2 more times.

Aspirate PBS and add 150~200 μl of the antibody dilution buffer, containing the desired secondary antibodies. Incubate the plate at room temperature for 1 h in a dark drawer.

Aspirate the secondary antibody-containing buffer and add 500 μl PBS. Wash out the remnant of the antibody.

Repeat washing with 500 μl PBS 2 more times.

Aspirate PBS and add DAPI (1:5000) in PBS.

Observe the samples under a immunofluorescence microscope. You don’t need to wash out DAPI. If you need quantification of SIX2+ cells with immunocytochemistry, use standard image software such as ImageJ 4,15. Alternatively, use flow cytometry for SIX2+ cells with the same antibody dilution ratio (1:500) as for immunocytochemistry 15.

Table 2.

Antibody list

| Antigen | Host | Supplier | Cat. No. | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-SMA | Mouse | Sigma | F3777 | 1:500 |

| Aquaporin2 | Rabbit | Millipore | AB3274 | 1:100 |

| E-cadherin (CDH1) | Rat | Abcam | ab11512 | 1:500 |

| Endomucin | Rat | Abcam | ab45771 | 1:500 |

| HOXD11 | Mouse | Sigma | SAB1403944 | 1:500 |

| KIM1 | Goat | R&D | AF1750 | 1:500 |

| Laminin | Rabbit | Sigma | L9393 | 1:500 |

| LHX1 | Mouse | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank | 4F2-c | 1:50 |

| LTL (lotus tetragonolobus lectin) | Biotin conjugated | Vector lab | B-1325 | 1:200 |

| PAX8 | Rabbit | Proteintech | 10336-1-AP | 1:500 |

| PDGFR-b | Goat | Novus | AF385 | 1:100 |

| Podocalyxin (PODXL) | Goat | R&D systems | AF1658 | 1:500 |

| SIX2 | Rabbit | Proteintech | 11562-1-AP | 1:500 |

| Uromodulin | Rabbit | Biomedical Technologies | BT-590 | 1:150 |

| WT-1 | Rabbit | Santa cruz | sc-192 | 1:50 |

B Endpoint analysis of 3D Kidney organoid, frozen sections TIMING 2 d

Transfer the kidney organoids into eppendorf tubes using a pipette with wide tips (simply cut the tip with scissors).

Gently aspirate the medium with a 200 μl pipette and add 500 μl 4% PFA. Incubate the organoids at room temperature for 1 h.

Gently aspirate 4% PFA with a 200 μl pipette and add 1 ml PBS. Wash the organoids.

Repeat washing with 1 ml PBS 2 more times.

Gently aspirate PBS with pipette and add 500 μl 30% (w/w) sucrose. Incubate the organoids overnight at 4 °C.

Transfer the organoids into the center of cryomolds with the wide-tipped pipette and gently aspirate 30% sucrose with a 200 μl pipette. Add OCT compound circumferentially around the periphery of the cryomolds.

Freeze the samples with liquid nitrogen and acetone.

Cut frozen sections of 5~10 μm thickness using a cryostat and mount the sections on glass slides.

Serially wash off the OCT compound using 3 Coplin jars filled with PBS.

Place ~30 μl of blocking buffer on each section after circling the section with a hydrophobic pen. Incubate the slides at room temperature for 1 h. CRITICAL STEP If you stain with biotinylated-LTL, it is necessary to use a streptavidin/biotin blocking kit.

Aspirate the blocking buffer and add ~30 μl of antibody dilution buffer, containing desired primary antibodies. Incubate the slides at room temperature for 1~2 h.

Aspirate antibody dilution buffer and wash with PBS 3 times.

Aspirate PBS and place ~30 μl of antibody dilution buffer, containing desired secondary antibodies. Incubate the slides at room temperature for 1 h in a dark drawer.

Aspirate antibody dilution buffer and wash with PBS 3 times.

Seal the sections using a cover glass slide and Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI.

Observe the samples under a immunofluorescence microscope or by confocal microscopy.

C Endpoint analysis of 3D kidney organoids by whole mount staining TIMING 3 d

Transfer the kidney organoids into eppendorf tubes using a pipette with wide tips (simply cut the tip with scissors).

Aspirate the medium with pipette gently and add 500 μl 4% PFA. Incubate the organoids at room temperature for 1 h.

Aspirate 4% PFA and add 1 ml PBS. Wash the organoids.

Repeat washing with 1 ml PBS 2 more times.

Gently aspirate PBS with a 200 μl pipette and add 200 μl blocking buffer. Incubate the organoids at room temperature for 1 h.

Gently aspirate blocking buffer with a 200 μl pipette and add 200 μl antibody dilution buffer, containing desired primary antibodies. Incubate the organoids overnight at 4 °C.

Gently aspirate antibody-containing solution with a 200 μl pipette and add 1 ml PBS. Incubate the organoids at room temperature for 1 h.

Gently aspirate PBS with a 200 μl pipette and add 1ml PBS. Incubate the organoids at room temperature for 1 h.

Gently aspirate PBS with a 200 μl pipette and add 1ml PBS. Incubate the organoid overnight at 4 °C.

Gently aspirate PBS with pipette and add 200 μl antibody dilution buffer, containing desired secondary antibodies. Incubate the organoids at room temperature for 1 h.

Gently aspirate secondary antibody-containing buffer with a 200 μl pipette and wash the organoids with 1ml PBS 3 times.

Gently aspirate PBS with a 200 μl pipette and add 200 μl of DAPI (1:5000) in PBS. Incubate the organoids at room temperature for 1 h.

Transfer the organoids onto glass slides with a pipette with wide tips. Aspirate DAPI solution and seal with Vectashield and a cover glass slide.

Observe the samples under a confocal microscope.

TIMING

Steps 1–6, maintenance of hPSCs without feeder cells: 7 d

Steps 7–13, preparation of hPSCs for differentiation: 3 d

Steps 14–22, differentiation of hPSCs into NPCs: 7–9 d

Steps 23A, B, differentiation of NPCs into kidney organoids: 12~ d

Steps 24A, B, C, endpoint analysis: 2–3 d

TROUBLESHOOTING

See Table 1 for troubleshooting guidance.

TABLE 1.

Troubleshooting.

| Step | Problem | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1, 12, 15 | The maintenance of hPSCs in ReproFF2 is difficult. | The use of ReproFF2 works well to produce highly efficient differentiation. Some lines of hPSCs, however, are difficult to maintain pluripotent in ReproFF2. In that case, we recommend the use of StemFit Basic (Ajinomoto, ASB01) which makes the maintenance of pluripotency of hPSCs without feeder cells much easier (Box 1). If you use StemFit Basic, you should test lower plating density (6,000~18,000 cells/cm2) when you prepare cells for the differentiation, since cells survive very well in StemFit. If you want to use other maintenance media, we recommend that you test different plating densities to achieve ~50% confluency when you start the differentiation, and to adjust the concentration of CHIR (3~10 μM). If those adjustments are not sufficient to induce SIX2+ cells, we recommend that you test addition of a BMP4 inhibitor (noggin: 5~25 ng/ml, or dorsomorphin: 100~500 nM). |

| 23Ai, 23Bi | The cells spontaneously differentiate into renal vesicle-like cells. | In some cell lines, the differentiation is faster than usual. In that case, switch to the next differentiation step with CHIR 3 μM and FGF9 (10 ng/ml) after 1 day of FGF9, 10 ng/ml, treatment alone. |

| 23Aiv, 23Bviii | The cells do not form renal vesicle-like structures and do not express LHX1. | After CHIR 3 μM treatment with FGF9 10 ng/ml for 2 days, feed cells every day for 3 days with the basic differentiation medium supplemented with FGF9 10 ng/ml. If it is not sufficient, test different concentrations of CHIR (2~5 μM) and/or FGF9 (10~200 ng/ml). Soon after FGF9 treatment at step 23Aiv or 23Bviii, you may not be able to recognize the renal vesicle-like structure with a microscope, but if you wait for 1 week then nephron-like structures should be apparent. |

ANTICIPATED RESULTS

With this protocol, SIX2+ NPCs should be induced with 80~90% efficiency on day 7~9 of differentiation. Subsequent differentiation from NPCs will generate kidney organoids which contain nephron epithelial cells and interstitial cells after removal of FGF9 from the differentiation medium on day 14. 3D organoids are approximately 0.5 mm in diameter, and each organoid contains multiple nephron structures. If the induction rate of NPCs are high (~80%), the reproducibility of kidney organoid generation in each well of 96-well plates will be very high (~100%). Usually, 3~6 wells of 24-well plates are sufficient to generate 96 organoids in 3D culture. The organoids are stable for 3 months at least.

For reproducible results, it is vital to prepare fresh medium and use well-preserved growth factors and small molecules. We suggest making small aliquots of medium, growth factors and small molecules and store them at −20 °C. Each time you dilute the growth factors in the differentiation medium, we recommend using fresh aliquots. In addition, the condition of the maintenance culture of hPSCs is critical for the differentiation efficiency. We recommend at least 3 replicates for every single experiment to confirm reproducible results for the induction of NPCs.

For successful induction of NPCs, the first step of differentiation with CHIR (+/− BMP4 inhibitor) is critical. Even if you obtain high efficiency of posterior IM induction specified by WT1+HOXD11+, this does not guarantee the efficient induction of NPCs. If the induction is less than optimal, we recommend you adjust the protocol (plating density, CHIR concentration, addition of BMP4 inhibitor at different doses). Use the morphology on day 4 of the differentiation (after CHIR treatment) as a guide to find the optimal concentrations and density of plating (Fig. 2). Too dense or too loose cluster formation will result in poor induction efficiency of NPCs. With a microscope look for loosely dense clusters of cells, and confirm the induction efficiency of NPCs on day 8–9 of differentiation. Generally, more than 80% of the cells express SIX2, if the protocol adjustment is appropriate.

After nephron progenitor cell induction, a protocol adjustment is not usually required. The nephron structures will be apparent after several days of culture once you induce the renal vesicle stage. Segmented nephron structures will be observed by immunostaining in both 2D and 3D culture. Depending on the goal of your study, you can choose the characteristics of the culture system that you use to study the organoids.

Supplementary Material

(a) Immunostaining for PDGFR (platelet derived growth factor receptor beta) and endomucin in 3D kidney organoids. PEGFRβ was assessed by immunohistochemistry in 3D kidney organoids on day 65. Endomucin was evaluated by whole mount staining in 3D kidney organoids on day 24. Arrows indicate endomucin+ endothelia in a glomerular structure. (b) Immunohistochemistry for α-SMA (smooth muscle alpha-actin) in 3D kidney organoids on day 65. There was a small population of α-SMA+ interstitial cells in kidney organoids. (c) Immunohistochemistry for aquaporin-2 (AQP2) in CDH1+ tubule in 3D kidney organoids on day 35. AQP2+ tubules were found in only CDH1+ tubules, indicating presence of connecting tubules/collecting ducts in kidney organoids. Scale bars: 50 μm.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank N. Gupta for providing immunohistochemistry images of kidney organoids in Supplementary Figure 1. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R37 DK039773 and R01 DK072381 (J.V.B.), Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad (R.M.), ReproCell Stem Cell Research grant (R.M.), Brigham and Women’s Hospital Research Excellence Award (R.M.), Brigham and Women’s Hospital Faculty Career Development Award (R.M.), and Harvard Stem Cell Institute Seed grant (R.M.).

Footnotes

A UTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.M. and J.V.B. formulated the strategy for this study. R.M. designed and performed experiments. R.M. and J.V.B. wrote the manuscript. J.V.B. helped to design experiments and to interpret the results.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

J.V.B. is a coinventor on KIM-1 patents, which have been licensed by Partners Healthcare to several companies. He has received royalty income from Partners Healthcare. J.V.B. or his family has received income for consulting from companies interested in biomarkers: Sekisui, Millennium, Johnson & Johnson, and Novartis.

References

- 1.Takahashi K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takasato M, et al. Directing human embryonic stem cell differentiation towards a renal lineage generates a self-organizing kidney. Nature cell biology. 2014;16:118–126. doi: 10.1038/ncb2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam AQ, et al. Rapid and efficient differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intermediate mesoderm that forms tubules expressing kidney proximal tubular markers. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2014;25:1211–1225. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taguchi A, et al. Redefining the in vivo origin of metanephric nephron progenitors enables generation of complex kidney structures from pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vigneau C, et al. Mouse embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies generate progenitors that integrate long term into renal proximal tubules in vivo. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2007;18:1709–1720. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce SJ, et al. In vitro differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells toward a renal lineage. Differentiation; research in biological diversity. 2007;75:337–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morizane R, Monkawa T, Itoh H. Differentiation of murine embryonic stem and induced pluripotent stem cells to renal lineage in vitro. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2009;390:1334–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narayanan K, et al. Human embryonic stem cells differentiate into functional renal proximal tubular-like cells. Kidney international. 2013;83:593–603. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morizane R, et al. Kidney specific protein-positive cells derived from embryonic stem cells reproduce tubular structures in vitro and differentiate into renal tubular cells. PloS one. 2013;8:e64843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mae S, et al. Monitoring and robust induction of nephrogenic intermediate mesoderm from human pluripotent stem cells. Nature communications. 2013;4:1367. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia Y, et al. The generation of kidney organoids by differentiation of human pluripotent cells to ureteric bud progenitor-like cells. Nature protocols. 2014;9:2693–2704. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takasato M, et al. Kidney organoids from human iPS cells contain multiple lineages and model human nephrogenesis. Nature. 2015;526:564–568. doi: 10.1038/nature15695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedman BS, et al. Modelling kidney disease with CRISPR-mutant kidney organoids derived from human pluripotent epiblast spheroids. Nature communications. 2015;6:8715. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morizane R, et al. Nephron organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells model kidney development and injury. Nature biotechnology. 2015;33:1193–1200. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iimura T, Pourquie O. Collinear activation of Hoxb genes during gastrulation is linked to mesoderm cell ingression. Nature. 2006;442:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature04838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deschamps J, van Nes J. Developmental regulation of the Hox genes during axial morphogenesis in the mouse. Development. 2005;132:2931–2942. doi: 10.1242/dev.01897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lengerke C, et al. BMP and Wnt specify hematopoietic fate by activation of the Cdx-Hox pathway. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobbs RF, Song H, Huso DL, Sundel MH, Sgouros G. A nephron-based model of the kidneys for macro-to-micro alpha-particle dosimetry. Physics in medicine and biology. 2012;57:4403–4424. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/13/4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devuyst O, et al. Rare inherited kidney diseases: challenges, opportunities, and perspectives. Lancet. 2014;383:1844–1859. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60659-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cong L, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sterneckert JL, Reinhardt P, Scholer HR. Investigating human disease using stem cell models. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2014;15:625–639. doi: 10.1038/nrg3764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taguchi A, Nishinakamura R. Nephron reconstitution from pluripotent stem cells. Kidney international. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osafune K, et al. Marked differences in differentiation propensity among human embryonic stem cell lines. Nature biotechnology. 2008;26:313–315. doi: 10.1038/nbt1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deen PM, et al. Assignment of the human gene for the water channel of renal collecting duct Aquaporin 2 (AQP2) to chromosome 12 region q12-->q13. Cytogenetics and cell genetics. 1994;66:260–262. doi: 10.1159/000133707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humphreys BD, et al. Fate tracing reveals the pericyte and not epithelial origin of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. The American journal of pathology. 2010;176:85–97. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samulowitz U, et al. Human endomucin: distribution pattern, expression on high endothelial venules, and decoration with the MECA-79 epitope. The American journal of pathology. 2002;160:1669–1681. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakagawa M, et al. A novel efficient feeder-free culture system for the derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4:3594. doi: 10.1038/srep03594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe K, et al. A ROCK inhibitor permits survival of dissociated human embryonic stem cells. Nature biotechnology. 2007;25:681–686. doi: 10.1038/nbt1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennett CN, et al. Regulation of Wnt signaling during adipogenesis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:30998–31004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaidya VS, Ramirez V, Ichimura T, Bobadilla NA, Bonventre JV. Urinary kidney injury molecule-1: a sensitive quantitative biomarker for early detection of kidney tubular injury. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2006;290:F517–529. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00291.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaidya VS, et al. Kidney injury molecule-1 outperforms traditional biomarkers of kidney injury in preclinical biomarker qualification studies. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28:478–485. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freedman BS, et al. Reduced ciliary polycystin-2 in induced pluripotent stem cells from polycystic kidney disease patients with PKD1 mutations. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2013;24:1571–1586. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012111089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(a) Immunostaining for PDGFR (platelet derived growth factor receptor beta) and endomucin in 3D kidney organoids. PEGFRβ was assessed by immunohistochemistry in 3D kidney organoids on day 65. Endomucin was evaluated by whole mount staining in 3D kidney organoids on day 24. Arrows indicate endomucin+ endothelia in a glomerular structure. (b) Immunohistochemistry for α-SMA (smooth muscle alpha-actin) in 3D kidney organoids on day 65. There was a small population of α-SMA+ interstitial cells in kidney organoids. (c) Immunohistochemistry for aquaporin-2 (AQP2) in CDH1+ tubule in 3D kidney organoids on day 35. AQP2+ tubules were found in only CDH1+ tubules, indicating presence of connecting tubules/collecting ducts in kidney organoids. Scale bars: 50 μm.