Abstract

Background: Collection of a complete and accurate medication history is an essential component of the medication reconciliation process. The role of pharmacy technicians in supporting medication reconciliation has been the subject of recent interest.

Purpose: The purpose of this article is to review the existing literature on pharmacy technician involvement in the medication reconciliation process and to summarize outcomes on the quality and accuracy of pharmacy technician–collected medication histories.

Method: A literature review was conducted using MEDLINE and Academic Search Premier (1948 – April 2015).

Results: Sixteen papers were identified, with 12 containing a formal evaluation of outcomes. Three were purely descriptive, and 9 compared the pharmacy technician's performance to pharmacists, nurses, physicians, and/or interdisciplinary teams. Studies used a variety of endpoints, but they demonstrated similar or improved outcomes by engaging pharmacy technicians. Evidence demonstrates that trained pharmacy technicians are able to gather medication histories with similar completeness and accuracy to other health care professionals.

Conclusion: The use of pharmacy technicians may be a viable strategy for developing and expanding medication reconciliation processes with appropriate supervision. Future efforts should focus on evaluating the impact of expanded roles for pharmacy technicians in the health care system; assessing the need for standardization of pharmacy technician education, training, and certification; and obtaining clarification from state pharmacy boards regarding these expanded roles.

Keywords: medication discrepancies, medication errors, medication reconciliation, pharmacy service, pharmacy technician

According to the Institute of Medicine, the average hospitalized patient experiences at least one medication error per day.1 It is further estimated that 67% of admitted patients have at least one error in their medication history, with 11% to 59% of those classified as clinically important.2 At a cost of $2,595 to $4,685 per adverse drug event (ADEs), the total costs attributable to ADEs have been estimated to exceed $5 million annually for a typical teaching hospital.3 Findings from these studies as well as others have led the health care community, professional organizations, and regulatory entities to demand more structured processes for comparing medication histories and resolving discrepancies during care transitions.4–6

A key component to medication reconciliation is the creation of the best possible medication history (BPMH). The BPMH uses information gathered from the community pharmacy, medical record, structured interview(s) with patients and/or caregivers, and other sources to develop the most accurate and complete medication history.6 Due to their knowledge and skills, pharmacists are well positioned to collect a BPMH and assist in the medication reconciliation process. Multiple studies have demonstrated that pharmacists identify a greater number of discrepancies and complete more medication interventions than physicians and nurses.7–10 However, each medication reconciliation takes 15 to 30 minutes per patient,11 with some studies reporting upwards of 90 minutes for geriatric patients.12 Similar to those reported in the nursing literature,13 time and staff resources are likely to be significant barriers to active pharmacist engagement. It may be unrealistic to expect that pharmacists will be able to collect a BPMH for every patient engaged in a care transition. This provides an impetus to evaluate the role of other health care professionals in the medication reconciliation process.

Pharmacy technicians are familiar with typical dosage forms, strengths, and schedules for a wide range of medications, and they may serve as a valuable resource in collecting information and generating the BPMH. The purpose of this article is to review the published literature surrounding the use of pharmacy technicians in generating a BPMH within the medication reconciliation process, describe the different reported technician programs, and summarize the available outcomes regarding quality and accuracy after program implementation.

METHODS

A literature review was conducted using MEDLINE (1948 – April 2015) and Academic Search Premier using the search terms “pharmacy technician” or “pharmacists' aides” and “medication reconciliation” or “medication history.” Additional relevant literature was then located by reviewing bibliographies and articles identified through MEDLINE's “Find Similar Result” function. Articles were independently reviewed to determine inclusion. To be included, the study needed to include pharmacy technicians in the medication reconciliation process and to report outcome(s) regarding quality or accuracy of the intervention. Articles could not be strictly descriptive of a program or service that integrated pharmacy technicians into the medication reconciliation process.

RESULTS

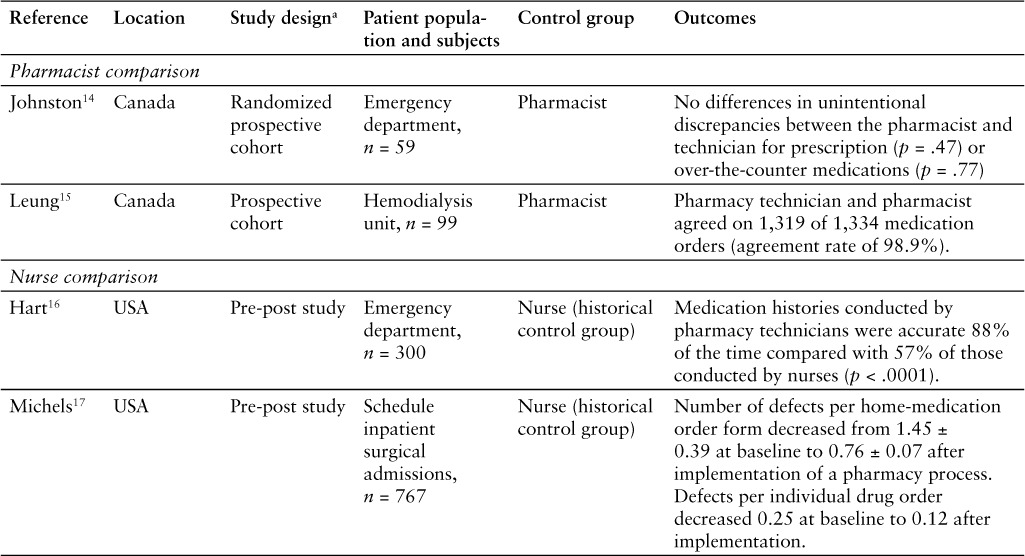

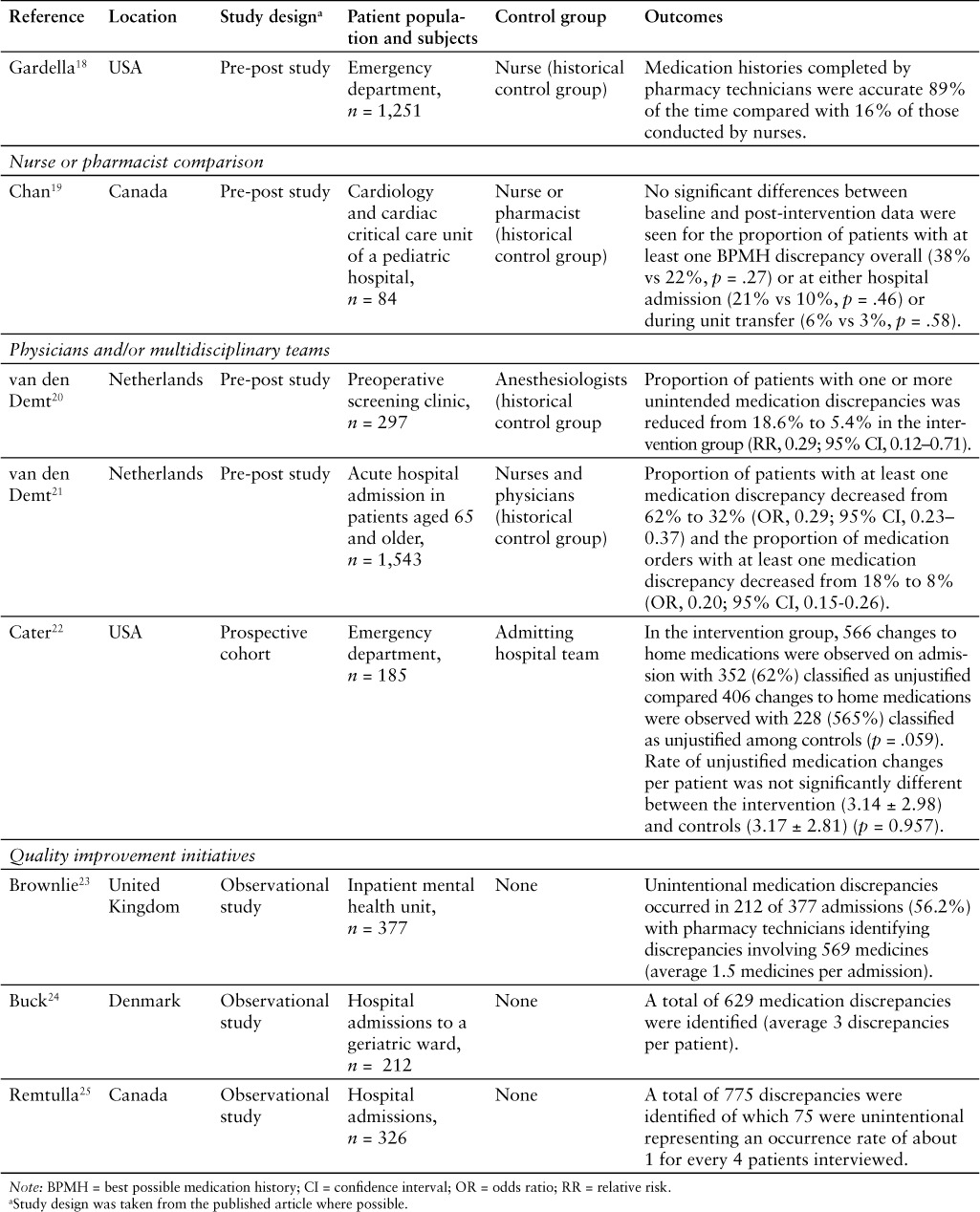

A total of 16 articles were identified for full review by study investigators. Four articles were excluded, as they were purely descriptive or reported workflow process endpoints. This left 12 articles that contained a formal evaluation of outcomes (Table 1). Nine studies compared the medication histories collected by the pharmacy technicians to those collected by other health care professionals (ie, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, or interdisciplinary teams) and 3 documented the impact of the pharmacy technician engagement without a formal comparator group.

Table 1.

Studies involving pharmacy technicians in the medication reconciliation process

Pharmacists Comparison

Two articles were identified in which pharmacists served as the control group. The first study reported a prospective comparison of medication histories obtained by pharmacy technicians and pharmacists at a 400-bed community hospital (The Moncton Hospital, New Brunswick, Canada). During December 2008, patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) were interviewed twice, once by a pharmacy technician and once by a pharmacist in a randomly assigned order. The 2 medication histories were then compared by investigators to determine the BPMH and the number of medication discrepancies. Fifty-nine patients were included in the analysis. Patients were 61.3 ± 18.6 years of age and taking 6.2 ± 4.6 prescription medications and 1.9 ± 1.8 over-the-counter or herbal products. Pharmacists and technicians had no unintentional discrepancies for prescription medications in 47 patients and 50 patients (p = .47), respectively, or in over-the-counter medications in 52 patients and 53 patients (p = .77), respectively. There was no significant difference between pharmacists and pharmacy technicians with respect to the number of discrepancies identified per patient involving prescription (0.25 ± 0.54 vs 0.24 ± 0.68; p = .88) or over-the-counter (0.14 ± 0.39 vs 0.15 ± 0.48; p = .83) medications. The study concluded that trained pharmacy technicians were able to obtain a medication history with similar accuracy and completeness as pharmacists.14

In the second study, patients admitted to a hemodialysis unit at an academic medical hospital (St Paul's Hospital, Vancouver, British Columbia) received an in-person interview by both a pharmacy technician and a pharmacist to collect the BPMH. The primary endpoint was the rate of agreement between the pharmacy technician and pharmacist for the recorded medication history. A total of 99 patients were interviewed between May and August 2008. Patients were 67 years of age (range, 19–96 years) and on 13.5 medications (range, 5–23 medications). A total of 1,334 medication orders were reviewed; the technician and pharmacist agreed on all but 15 orders, equaling an agreement rate of 98.9%. In this process, a total of 358 medication discrepancies were identified in 93 patients, equaling 3.8 discrepancies per patient. Investigators concluded that pharmacy technicians were capable of interviewing patients to create an accurate medication history and this was a useful approach to identify medication discrepancies and potential drug-related problems.15

Nurse Comparison

Three studies were identified in which nurses served as the control group. In the first study, investigators reported the results of a pre-post study comparing a historical control group in which nurses were responsible for medication history collection to a prospective cohort involving the implementation of a pharmacy technician–driven program. The study was conducted in the ED of a 687-bed community hospital (Morton Plant Hospital, Clearwater, FL) from November 2011 to February 2012. Primary endpoint was percentage of patients with an accurate medication history as determined by a pharmacy resident upon comprehensive review of the medical record. Patients interviewed by the nurses (n = 150) were 67 ± 19.4 years of age with 10.3 ± 5.6 medications compared to 70 ± 17.3 years (p = .144) with 12.3 ± 6.2 medications (p = .003) for those interviewed by the pharmacy technicians (n = 150). Medication histories were conducted by the pharmacy technicians without any identifiable errors in 88% of instances compared with 57% of those completed by nurses (p < .0001). Nineteen errors (1.1%) were made by pharmacy technicians versus 117 errors (8.3%) by nurses (p < .0001). The study concluded that trained pharmacy technicians could assist providers and nurses in obtaining more accurate medication histories in the ED.16

The second study described a program using pharmacy technicians to reduce potential ADEs during the conversion of outpatient medication orders to active inpatient orders in scheduled surgical admissions. The program was implemented at a community hospital (Fairview Southdale Hospital, Edina, MN) and contained 3 parts: use of a standardized home-medication order form, utilization of pharmacy technicians in the admissions department, and a hospital policy prohibiting the use of blanket orders. The goal was to decrease potential ADEs in surgical admission by 80% over a 4-month period. Potential ADEs were measured by the number of defects on admission medication history; defect was defined as the omission of key information, the presence of incorrect information, the ordering of an inappropriate drug for the condition, an illegible order, a serious drug interaction, or the continuation of a previously discontinued drug. With the implementation of the standardized home-medication order form, nurses were initially responsible for collecting a medication history upon the patient's arrival for the procedure. However, in an effort to incorporate this step into the presurgical admission process and respond to nursing workload constraints, the responsibility for collecting medication histories was shifted to pharmacy technicians. The technicians telephoned patients scheduled for surgery prior to admission to complete the home-medication order form, which was then reviewed by a pharmacist. In both workflows, the completed form was given to the physician to review and to determine whether to continue or modify therapy during inpatient admission. Nurses completed the home order forms from February 4 to March 17, 2002 (baseline); pharmacy technicians with pharmacist review completed the home order forms from March 18 to July 7, 2002 (intervention). Implementation of the pharmacy process decreased the average number of defects per order from 1.45 ± 0.39 (n = 182) at baseline to 0.76 ± 0.07 (n = 585) after intervention (p < .005). Defects per individual drug order also decreased from 0.25 (n = 1,056) at baseline to 0.12 (n = 3,620) after intervention (p < .005). Both represented a decrease of greater than 80% from baseline. The study concluded that a program involving trained pharmacy technicians reduced the number of problems in inpatient orders for scheduled surgical admissions.17

The final study reported the results of a medication reconciliation quality improvement project conducted at a not-for-profit integrated health care system encompassing 13 hospitals (Novant Health, Winston-Salem, NC). One project goal was to improve the accuracy of medication histories collected on patients admitted through the ED. Prior to the initiative, collection of the medication history was the responsibility of the admitting nurse. Baseline data were collected on the accuracy of these medication histories by having a pharmacist collect a BPMH within 24 hours of admission. Between October 2007 and May 2008, 2 medication histories were collected on 200 patients. It was determined that 32 (16%) of the histories obtained by nurses were accurate. Pharmacy technicians were then integrated into the EDs of 2 hospitals, and the accuracy of medication histories obtained by pharmacy technicians was then assessed by the same methods from June 2008 and December 2010. Dual histories were collected randomly on 1,251 patients. It was determined that 1,113 (89%) were accurate. The health system determined that pharmacy technicians could increase the accuracy of medication histories for patients admitted through the ED, allowing for expansion of the pharmacy technician–driven program.18

Nurse or Pharmacist Comparison

This study reported on the completeness and accuracy of medication histories collected through a pilot study involving pharmacy technicians. The study was conducted at teaching hospital (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario) in patients 18 years of age or younger who were admitted or transferred to either the cardiology ward or the cardiac critical care unit. Prior to the pilot study, baseline data were collected on the accuracy of the usual care process. In this process, a pharmacist or nurse practitioner obtained the BPMH and reconciled the history with admission or transfer orders. In the pilot program, the responsibility of creating and reconciling medication information was transferred to a pharmacy technician. The primary study endpoint was accuracy of the medication list as determined by a pharmacy resident upon a second interview. Both baseline and pilot data were collected over 3-week intervals with a total of 38 and 46 patients interviewed, respectively. Demographics of patients in the baseline and pilot studies were similar in age (median [range] 9.0 months [1 day to 17 years] vs 5.9 months [3 days to 16 years], respectively), but differed in the percentage of patients taking more than 3 prescription and/or nonprescription medications (29% vs 52 %; p = .043, respectively). No significant unintentional differences between baseline and pilot data were seen for the proportion of patients with at least one medication history discrepancy overall (38% vs 22%; p = .27) or at admission (21% vs 10%; p = .46) or transfer (6% vs 3%; p = .58). The authors concluded that a trained pharmacy technician could perform medication reconciliation for pediatric patients with accuracy comparable to nurses and pharmacists at both admission and transfer.19

Physicians and/or Interdisciplinary Teams Comparison

Three studies used physicians or physician-driven workflow as the comparator. The first study was conducted at a preoperative screening clinic affiliated with a general teaching hospital (TweeStenden, The Netherlands). Prior to the intervention, anesthesiologists reviewed the patient's medication history and drug allergies as part of preoperative screening process. As a result, the intervention consisted of adding a pharmacy technician who was responsible for collecting community pharmacy medication records prior to the preoperative appointment and then interviewing the patient at the appointment to reconcile this information before the patient was seen by the anesthesiologist. This list was reviewed by a pharmacist and then was provided to the anesthesiologist who could modify the drug list as appropriate during the medical screening process. In both the usual care and intervention processes, medication reconciliation was subsequently performed at the time of hospital admission. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients with one or more medication discrepancies between the 2 medication lists. Data were collected from 204 patients before the intervention (March to June 2007) and 93 after the intervention (July to August 2007). Patients were 59.1 ± 14.8 and 60.6 ± 16.7 years of age and taking 3.9 ± 3.2 and 4.5 ± 3.1 medications in the pre- and post-intervention groups, respectively. Proportion of patients with at least one medication discrepancy decreased from 18.6% to 5.4% following intervention implementation (relative risk [RR], 0.29; 95% CI, 0.12 to 0.71). The study concluded that pharmacy technicians could be integrated into preoperative clinics to reduce the number of medication discrepancies.20

The second study was a multicenter study conducted on patients 65 years old or older admitted through the ED in 12 hospitals across the Netherlands that ranged from academic medical centers to community hospitals. Before the intervention, medication history taking was the responsibility of physicians and nurses in the ED or unit to which the patient was transferred. The intervention then consisted of the introduction of the BPMH as previously described. In most hospitals, the intervention consisted of pharmacy technicians obtaining BPMH while under the supervision of a pharmacist; however, 3 hospitals employed a “mixed model” where the BPMH was obtained by either a physician or pharmacy technician trained in the BPMH collection process. The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients with one or more unintended medication discrepancies and the proportion of medication orders with one or more unintended medication discrepancies as determined by an independent observer. Data were collected from March 2010 to July 2012 with 1,543 participants in the analysis (350 participants from the mixed model hospitals). In the pre- and post-intervention periods, patients were 78.8 ± 7.5 and 78.2 ± 7.7 years of age (p = .13) and taking 8.3 ± 4.5 and 8.4 ± 4.5 medications at admission (p = .82), respectively. Across all hospitals, the proportion of patients with at least one medication discrepancy decreased from 62% to 32% (odds ratio [OR], 0.29; 95% CI, 0.23–0.37) and the proportion of medication orders with at least one medication discrepancy decreased from 18% to 8% (OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.15–0.26). However, when stratifying results by intervention type, hospitals with a strictly pharmacy-based process experienced statistically significant reductions in both the proportion of patients with at least one medication discrepancy (63% vs 22%; OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.12–0.21) and proportion of medication orders with at least one medication discrepancy (19% vs 4%; OR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.15–0.21), while the mixed model hospitals saw an increase the proportion of patients with at least one medication discrepancy (53% vs 62%; OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 0.88–2.39) and proportion of medication orders with at least one medication discrepancy (12% vs 18%; OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.29–2.08). The study concluded that a pharmacy-based medication reconciliation program reduced medication discrepancies in acutely admitted elderly patients.21

The final study evaluated whether verification of medication histories by pharmacy technicians in the ED could decrease errors in initial inpatient medication regimens at an academic medical center (University of North Carolina Hospitals, Chapel Hill, NC). Hospital admission orders were compared to a pharmacy technician–obtained medication histories that were collected before admission (intervention) or after admission (control) and the discrepancies were classified as justified or unjustified. A total of 113 intervention and 75 control subjects were included. Patients were 54.3 ± 16.7 and 56.2 ± 15.8 years of age and taking 7.62 ± 4.38 and 8.16 ± 5.23 medications in the intervention and control groups, respectively. In the intervention group, 566 changes to home medications were observed on admission with 352 (62%) classified as unjustified compared 406 changes to home medications observed with 228 (56%) classified as unjustified among controls (p = .059). The rate of unjustified medication changes per patient was likewise not significantly different between the intervention (3.14 ± 2.98) and controls (3.17 ± 2.81) (p = .957). Investigators concluded that medication reconciliation by a pharmacy technician in the ED did not result in a significant decrease in unjustified medication discrepancies.22

Quality Improvement Initiatives

Three publications were identified that quantified the impact of engaging a pharmacy technician in the medication reconciliation process, but they lacked a formal comparison group. In the first article, investigators reported the prevalence of medication discrepancies identified through a pharmacy technician–led medication reconciliation process within a 20-bed inpatient unit specializing in mental health problems and learning disabilities (Basildon Mental Health Unit, South Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust, UK). The pharmacy technician gathered a BPMH and then met with the clinical team to determine whether discrepancies identified were intentional or unintentional. During the study period, March to June 2012, 377 unit admissions were reconciled by the pharmacy technicians. Patients admitted were aged 44.5 ± 17.2 years and were taking 4.65 ± 3.19 medications. An unintentional medication discrepancy was identified in 212 admissions (56.2%) involving 569 medicines (1.5 medicines per admission). The study concluded that medication discrepancies are common within mental health services and trained pharmacy technicians were able to lower the frequency of discrepancies. 23

In the second article, investigators reported the prevalence of medication discrepancies identified through a pharmacy technician–led medication reconciliation process in a 35-bed inpatient geriatric ward (Odense University Hospital, Denmark). Over a 7-week period, 2 pharmacy technicians conducted medication reconciliation and focused medication reviews according to a cooperative agreement. Upon hospital admission, physicians entered the patient's medication history; afterwards the pharmacy technicians reviewed the history using information from a variety of sources to identify any discrepancies. A total of 212 medication reconciliations were conducted with 629 discrepancies identified (3 discrepancies per patient); of those, 45% were ultimately accepted and corrected by physicians. Investigators concluded that pharmacy technicians could contribute to a significant reduction in medication discrepancies in acutely admitted patients through medication reconciliation.24

Finally, investigators reported the prevalence of medication discrepancies identified through a pharmacy technician–led medication reconciliation process for patients admitted to surgical and medical wards of a 440-bed tertiary care hospital (Providence Health Care, Vancouver, British Columbia). Each morning, all patients admitted in the previous 24 hours were identified, and then a BPMH was created by a pharmacy technician. Any discrepancies were communicated to a pharmacist who determined whether there was a need to alter drug therapy and/or contact the prescriber. Data were collected for a pilot program that ran from January 14, 2008 to March 6, 2008 (39 working days). The pharmacy technicians completed interviews on 325 patients (8 patients per day) taking 1,345 medications (4 medications per patient). The technicians identified 775 discrepancies, of which 75 were unintentional; this represented an occurrence rate of about 1 for every 4 patients interviewed. Results supported the concept of using pharmacy technicians to obtain BPMH. 25

DISCUSSION

The use of pharmacy technicians to create a BPMH as part of the medication reconciliation process is becoming increasingly common. To our knowledge, this is the first review of current literature that examines this expanded role for pharmacy technicians. Twelve observational studies were identified quantifying the impact of pharmacy technician engagement as compared to usual care processes involving nurses, physicians, and pharmacists. The literature supports that pharmacy technicians are capable of identifying medication discrepancies and collecting medication histories with a similar level of accuracy as other health care professionals.

A number of other important issues were identified through the review of this literature. First, pharmacy technicians identified medication discrepancies in approximately 25% to 50% of patients, illustrating the widespread problem of medication history inaccuracy. 14,19,21,23,25 Second, many studies reported that it took 15 to 30 minutes per patient for pharmacy technicians to collect a medication history.14,15,23–25 This estimate is consistent with past reports,11 further demonstrating that medication reconciliation is a resource-intensive activity. Since health care organizations may lack the resources to deploy highly trained personnel – whether they be physicians, nurses, or pharmacists – to the standard workflow, pharmacy technicians may represent a more cost-effective alternative to ensure a BPMH is obtained on all patients. Third, although outside of the scope of this review, several articles also reported on the relationship between medication discrepancies and the potential for a medication error or other adverse medication-related outcome. Articles reported that involvement of pharmacy technicians translated to an increased perception by health care professionals that the process was safer and more accurate,17 improved documentation of the last date and time for high-risk anticoagulants and antiplatelets,16 or reported on the likelihood that discrepancies could cause either moderate or severe discomfort or clinical deterioration.14,15 A random sample of 20% of identified discrepancies were evaluated for severity in one study. If those had been corrected within 16 days, then the potential harm was estimated to be minor in 62.3% and moderate in 37.7% of patients; however, if they had not been corrected, then the potential harm was estimated to be minor in 23.7% and moderate in 87% of patients.23

Even though study results were generally supportive of engaging pharmacy technicians in medication reconciliation efforts, these results should be interpreted with caution as they are limited in several ways. Identified studies were heterogeneous with respect to the study design, primary endpoints, and medication reconciliation processes; as a result, pooling data into a meta-analysis would be challenging and likely inappropriate. Additionally, because the comparator group(s) varied dramatically between studies, it is likely that some of the usual care processes may not have reflected a collection of a true BPMH. It is difficult to conclude that pharmacy technicians obtained more accurate medication histories than other health care professionals when other professionals may not have been trained in collection of a BPMH and were likely collecting this information alongside numerous other clinical responsibilities. Only 3 papers included in this review were conducted in the United States. The majority of articles were from outside the United States, including Canada, the Netherlands, Denmark, and United Kingdom. This is especially relevant due to the differences in the training and education of pharmacy technicians. In the Netherlands, for example, pharmacy technicians are trained in medication preparation, dispensing, patient education, and medication reconciliation.21 In Denmark, pharmacy technicians receive 3 years of formal education that includes both a didactic and experiential component, and they are allowed to complete select medication interventions while collecting the BPMH.24 Differences in health care systems also impact access to information. Articles cited the use of centralized electronic systems containing information on all prescriptions and medication purchases. 24 Outside of a small number of health systems (eg, Kaiser Permanente, Veterans Administration), similar platforms do not exist in the United States. As a result, due to the significant difference in technician education/training and access to information, generalizing this information to the United States should be done cautiously and with knowledge of these limitations.

Four papers were identified that discussed integration of a pharmacy technician into medication reconciliation processes in the United States. They were not included in this review because they focused on workflow process measures,26 such as whether all the medications listed had a name, dose, and frequency, or contained limited information on how the quality of the pharmacy technician's work was assessed.27–29

Considering all reports of pharmacy technician engagement, several best practices emerged: (a) creating a standardized process for collection of the medication history and defining a specific patient populations,14,15,21,24,25,27,28 (b) choosing pharmacy technicians with past experience in hospital and community pharmacy settings as well as those who demonstrate good interpersonal, communication, and problem-solving skills,16,17,25,27 (c) having pharmacy technicians who are dedicated to medication reconciliation efforts,16,17,27–29 (d) educating the hospital staff regarding the new process and how it may impact and improve their current workflows as well as patient safety,24,28 and (e) establishing an internal training program for technicians in these roles led by pharmacists and/or experienced pharmacy technicians. Training programs generally included an education component (either didactic or through background reading and discussion), training on how to complete medication reconciliation or compile a BPMH, observation of a medication reconciliation interview completed by a pharmacist or pharmacy technician, practice or completion of a medication reconciliation interview while being observed, and finally a competency assessment. 14–17,21,24,25,27–29 Some programs have also incorporated quality assurance audits and observed interviews that take place throughout the year.27

One study identified did not demonstrate a decrease in the rate of unjustified medication discrepancies among patients who had their medications verified before admission by a pharmacy technician as compared to the admitting team.21 It is important to consider these results, particularly in the context of the limitations identified above, but the authors speculate that the negative results may be accounted for by the admitting team failing to use the medication lists collected by the pharmacy technicians. Furthermore, there may not have been a decrease in medication discrepancies, but if a pharmacy technician could collect medication histories with similar accuracy and efficiency as the admitting team, then the admitting team might be free to focus on other clinical activities.

Outside of the area of medication reconciliation, research into expanding the role of the pharmacy technician is limited. There are some descriptive papers of innovative roles within collecting and organizing laboratory values (eg, pharmacokinetic or anticoagulation services), supporting formulary management, and screening patients for medication conversion programs (eg, IV-to-oral conversion programs).30–33 Additionally, there is recent literature formally evaluating the impact of a pharmacy technician within a clinical pharmacy osteoporosis management service.34 This literature, coupled with discussions within the profession that highlight the need for an expanded role of pharmacy technicians in the development of pharmacy practice35 and reports that pharmacy technicians support an expanded role,36 suggests that this is a likely area of expansion in the near future.

The notion of expanding the scope of the pharmacy technician practice raises a number of issues related to the variability of technician training and education. There may be a need for greater standardization with regard to education, training, and certification. It also raises a number of regulatory questions about the expanded role of pharmacy technicians as it relates to supervision and clinical judgment. Regulations in this area are evolving, but many Boards of Pharmacy are grappling with these issues, often after hospitals have already initiated programs. Moving forward, regulations and rules will need to be updated and interpreted with the new technician responsibilities and roles in mind.37

CONCLUSION

Current literature suggests that trained pharmacy technicians are capable of identifying medication discrepancies and collecting medication histories with accuracy similar to other health care professionals. Much of this information has been collected outside of the United States, so generalizability may be limited. Future research on the accuracy of pharmacy technician–obtained medication histories should be conducted in the United States to support expanded roles in medication reconciliation processes and support other clinical services.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Institute of Medicine. . Preventing Medication Errors. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tam VC, Knowles SR, Cornish PL, . et al. Frequency, type and clinical important of medication history errors at admission to hospital: A systematic review. CMAJ. 2005; 30: 510– 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ, . et al. The cost of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1997; 277: 307– 311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. . ASHP statement on the pharmacist's role in medication reconciliation. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013; 70: 453– 456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. The Joint Commission. . Sentinel event alert. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/sea_35.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2016. [PubMed]

- 6. MARQUIS Investigators. . MARQUIS Implementation Manual. A guide for medication reconciliation quality improvement. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/MARQUIS/Download_Manua_Medication_Reconciliation.aspx. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- 7. Reeder TA, Mutnick A.. Pharmacist-versus physician-obtained medication histories. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008; 65: 857– 860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nester TM, Hale LS.. Effectiveness of a pharmacist-acquired medication history in promoting patient safety. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002; 59: 2221– 2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cornish PL, Knowles SR, Marchesano R, . et al. Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165: 424– 429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gleason KM, Groszek JM, Sullivan C, . et al. Reconciliation of discrepancies in medication histories and admission orders of newly hospitalized patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004; 61: 1689– 1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gleason KM, Brake H, Agramonte V, Perfetti C.. Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) Toolkit for Medication Reconciliation. (Prepared by the Island Peer Review Organization, Inc., under Contract No. HHSA2902009000 13C.) AHRQ Publication No. 11(12)-0059 Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Revised August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meguerditchian AN, Krotneva S, Reidel K, Huang A, Tamblyn R.. Medication reconciliation at admission and discharge: A time and motion study. BMC Health Services Res. 2013: 13: 485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chevalier BA, Parker DS, MacKinnon NJ, Sketris I.. Nurses' perceptions of medication safety and medication reconciliation practices. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont). 2006; 19: 61– 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnston R, Saulnier L, Gould O.. Best possible medication history in the emergency department: Comparing pharmacy technicians and pharmacists. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2010; 63: 359– 365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leung M, Jung J, Lau W, Kiaii M, Jung B.. Best possible medication history for hemodialysis patients obtained by a pharmacy technician. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009; 62: 386– 391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hart C, Price C, Graziose G, Grey J.. A program using pharmacy technicians to collect medication histories in the emergency department. P T. 2015; 40: 56– 61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Michels RD, Meisel SB.. Program using pharmacy technicians to obtain medication histories. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003; 60: 1982– 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gardella JE, Cardwell TB, Nnadi M.. Improving medication safety with accurate preadmission medication lists and postdischarge education. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012; 38: 452– 458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chan C, Renee Woo, Seto W, . et al. Medication reconciliation in pediatric cardiology performed by a pharmacy technician: A prospective cohort comparison study. CJHP. 2015; 68: 8– 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van den Bemt PMLA, van den Broek S, van Nunen AK, . et al. Medication reconciliation performed by pharmacy technicians at the time of preoperative screening. Ann Pharmother. 2009; 43: 868– 874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van den Bemt PMLA, van der Schrieck-de Loos EM, van der Linden C, . et al. Effect of medication reconciliation on unintentional medication discrepancies in acute hospital admissions of elderly adults: A multicenter study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013; 61: 1262– 1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cater SW, Luzum M, Serra AE, . et al. A prospective cohort study of medication reconciliation using pharmacy technicians in the emergency department to reduce medication errors among admitted patients. J Emerg Med. 2015; 48: 230– 238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brownlie K, Schneider C, Culliford R, . et al. Medication reconciliation by a pharmacy technician in a mental health assessment unit. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014; 36: 303– 309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buck TC, Gronkjaer LS, Duckert ML, Rosholm JU, Aagaard L.. Medication reconciliation and prescribing reviews by pharmacy technicians in a geriatric ward. J Res Pharm Pract. 2013; 2: 145– 150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Remtulla S, Brown G, Frighetto L.. Best possible medication history by a pharmacy technician at a tertiary care hospital. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009; 62: 402– 405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smith SB, Mango MD.. Pharmacy-based medication reconciliation program utilizing pharmacists and technicians: A process improvement initiative. Hosp Pharm. 2013; 48: 112– 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cooper JB, Lilliston M, Brooks D, Swords B.. Experience with a pharmacy technician medication history program. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014; 71: 1567– 1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sen S, Siemianowski, Murphy M, McAllister SC.. Implementation of a pharmacy technician-centered medication reconciliation program at an urban teaching medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014; 71: 51– 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Knight H, Edgerton L, Foster R.. Pharmacy technicians obtaining medication histories within the emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010; 67: 512– 514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Koch KE, Weeks A.. Clinically oriented pharmacy technicians to augment clinical services. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1998; 55: 1375– 1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kliethermes MA, Schullo-Feulner AM, Tilton J, . et al. Model for medication therapy management in a university clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008; 65: 844– 856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ervin KCA, Skledar S, Hess MM, . et al. Data analyst technician: An innovative role for the pharmacy technician. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001; 58: 1815– 1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weber E, Hepfinger C, Koontz, Cohn-Oswald L.. Pharmacy technicians supporting clinical functions. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005; 62: 2466– 2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Irwin AN, Heilmann RMF, Gerrity TM, Kroner BA, Olson KL.. Use of a pharmacy technician to facilitate post-fracture care provided by clinical pharmacy specialists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014; 71: 2054– 2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Myers CE. Opportunities and challenges to pharmacy technicians in supporting optimal pharmacy practice models in health systems. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011; 68: 1128– 1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wilson DL, Kimberlin CL, Brushwood DB, . et al. Constructs underlying community pharmacy dispensing functions relative to Florida pharmacy technicians. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2007; 45: 588– 598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thompson CA. Legality of technician's involvement in medication reconciliation not clear. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009; 66: 433– 434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]